Abstract

Background

Female dermatologists often face the challenges of balancing a rewarding medical career with duties of home life and childrearing. Excessive responsibility at home or work can introduce barriers to balance and prove detrimental to the health and wellness of the physician.

Objective

We aim to perform a needs assessment through a series of survey questions with regard to home and work responsibilities and impacts on mental health.

Methods

Survey participants were selected from the Women’s Dermatologic Society through an e-mail invitation with a link to an anonymous survey tool and a paper questionnaire at the Women’s Dermatologic Society Forum in February 2019 in Dallas, Texas. The survey included 20 questions with regard to household responsibilities, child care, clinical responsibilities, specialty education, and impacts on personal time, sleep, and overall sense of well-being. There were a total of 127 respondents.

Results

Eighty-five percent of physicians in our cohort are currently married. A large percent of respondents utilized hired household help in the form of nannies to perform chores. Spousal contribution was emphasized in this cohort and often highlighted as an important factor in maintaining home life duties.

Conclusion

The professional women in our cohort may be balancing work and life at the expense of personal physical and mental health with little time to exercise and fewer hours of sleep per night.

Keywords: Work–life balance, female professionals, female dermatologists, Women’s Dermatologic Society, physician burnout

Introduction

The concept of work–life balance has gained increasing attention over the 20th century, largely due to shifts in perspectives on societal gender roles and a subsequent increase in the number of women who have entered the workforce (Pichler, 2009). The work–life balance of female physicians is particularly important because physicians experience higher rates of burnout compared with other professionals in society, independently of gender (Shanafelt et al., 2012). Physicians regularly face multifaceted demands in the workplace, including expanding administrative burdens, high patient-to-provider ratio, and intrinsic stressors of the occupation, that lead to higher rates of burnout than in other professions (Dorrell et al., 2019, Shanafelt et al., 2012). However, this is not accompanied by a reduction in household and personal obligations. Despite a cultural shift in shared household responsibilities between spouses, on average, married female physicians spend more time parenting children and attending to household responsibilities than male physicians on a weekly basis (Wietsma, 2014).

There are significant implications associated with combining the heavy burden of home–life responsibilities and maintaining or advancing a demanding career. Women comprise over 50% of medical students and nearly half of all residents in the United States; yet, the number of women in full-time and associate professorship positions and other academic leadership positions falls significantly below this number (Butkus et al., 2018, Wietsma, 2014). When compared with other medical specialties, dermatologists seem to enjoy lower rates of burnout and higher rates of satisfaction with amount of personal time (Shanafelt et al., 2012), but female dermatologists still face many of the same barriers to balancing life goals and work success as their female nondermatologist colleagues. For example, many female physicians delay pregnancy and childrearing to pursue medical school and/or residency (Wietsma, 2014), and many express regret for either delaying pregnancy or choosing a career in medicine or their specialty when later faced with difficulty conceiving (Osterweil, 2014).

In addition, individual and systemic gender biases in the field of medicine continue to perpetuate workplace inequality with respect to compensation, promotion, hiring, and treatment (Kang and Kaplan, 2019). A 2017 publication emphasizing the achievements of female dermatologists highlights gender discrepancies in the field, such as the low number (i.e., only six) female presidents of the American Academy of Dermatology during its 79-year history, funding inequalities, fewer women specializing in Mohs surgery and other postresident fellowships, and the constant antagonism between climbing the ranks of the academic ladder versus allocating time to having children (Margosian, 2017).

Objective

This survey-based study of female dermatologists in the Women’s Dermatological Society (WDS) aims to report data reflecting various parameters of work–life balance in this population. The ultimate purpose is to perform a needs assessment for women’s mentorship, training, and support system development in the dermatology community by identifying discrepancies and inadequacies in both their career and personal lives.

Methods

We created a 20-item survey with questions about household responsibilities, child care, clinical responsibilities, specialty education, and impacts on personal time, sleep, and overall sense of well-being. Survey participants were selected from the WDS membership base via an e-mail request for participation. The email included information about the study, instructions, and a link to an online anonymous survey tool to collect responses. The survey was administrated a second time to WDS members attending the WDS Forum Conference in Dallas, Texas, in February 2019. The total surveyed population included 1425 female dermatologists.

A total of 127 female dermatologists (8.9%) responded to the survey (Table 1). The survey questionnaire was designed to include three major categories relevant to work–life balance: personal life, professional responsibilities, and impacts on mental health and overall wellness. The survey included a total of 20 questions, including two demographics questions, three explicitly work-related questions, three mental health impact/wellness questions, and 12 personal/home responsibilities questions. Most questions had answer options that included both defined multiple choice answers and free-text write-in answers to ensure capture of the variety of experiences represented in this cohort. Data were kept anonymous throughout the study and collected at the end in tabular form automatically generated by the online assessment tool.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information

| Marital status | Physicians, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Single | 15 (12.6) |

| Divorced | 4 (3.1) |

| Married | 108 (85.0) |

Results

To comprehensively assess physician stressors and highlight predominant responsibilities within each realm of work–life balance, the questions were specific and individual responses (nonmultiple choice) were taken into account and reported, as were general trends. The results were stratified by the three major categories of questions: work life, personal life, and impacts on mental health. The results are presented in both narrative form, highlighting major trends, and tabular form, presenting all relevant data collected.

Work/career-related responsibilities

We focused on two broad, traditional, work-related responsibilities that are relevant to dermatologist subspecialists: time spent with patient encounters and time spent maintaining subspecialty knowledge and updates in the literature.

The largest portion of dermatologists (29.0%) in our cohort spent ≥ 40 hours/week seeing patients (Table 2). This does not include hours spent managing electronic health records, patient charts, and notes, which significantly increases the number of working hours. Additionally, reading major journal publications represents an important part of subspecialty maintenance of education and relevant clinical practice. Spare time at the office was reported as the most common opportunity used for reading journals (46.3%), with the second most common being journal club meetings held outside of normal clinic hours (31.3%; Table 3). Interestingly, > 10% of participants reported a complete lack of journal reading with the response “I don’t” on the survey or with individual responses indicating a lack of time to keep up with journals. Continuing medical education credit, which represents an official maintenance of subspecialty knowledge, was obtained most commonly through academic meetings, both large annual meetings (86.6%) and home academic institution meetings (55.2%; Table 4).

Table 2.

Hours spent seeing patients

| Hours spent in patient encounters/week |

Physicians, n (%) (N = 124) |

|---|---|

| < 8 | 14 (11.3) |

| 9-16 | 5 (4.0) |

| 17-24 | 13 (10.5) |

| 25-32 | 25 (20.2) |

| 33-40 | 31 (25.0) |

| > 40 | 36 (29.0) |

Table 3.

Subspecialty education through journal reading

| When is time spent reading journals? | Physicians, n (%) (N = 67) |

|---|---|

| I don’t | 7 (10.5) |

| During down time at the office | 31 (46.3) |

| To relax at night | 9 (13.4) |

| Dedicated weekly or monthly time set aside | 5 (7.5) |

| At journal club | 21 (31.3) |

| Individual responses | |

| “Commuting time on train; while waiting for children’s dance and sports practices” “In the morning while eating breakfast” “Binge in preparation for lectures and talks” “As time permits” “With an eye open before bed (aka I don’t really)” “Weekend before journal club” “When I am preparing talks for teaching for the residents” “At breakfast” “Planes, trains” |

Table 4.

Continuing medical education credit

| How continuing medical education credit is obtained | Physicians, n (%) (N = 67) |

|---|---|

| At large annual/professional meetings | 58 (86.6) |

| With academic meetings at home institution | 37 (55.2) |

| Online | 23 (34.3) |

| Other | 6 (9.0) |

| Individual responses | |

| “Writing and reviewing” “Work at academic center, get CME easily by conference and grands rounds work” “Research projects and training trainees” “Dialogues in dermatology” “Dialogues in derm podcast which I listen to while commuting” “State society meetings” |

Personal responsibilities/home life

This broad category encompasses a variety of personal obligations and responsibilities. Three major subcategories further stratify this information into child/dependent-related responsibilities, grocery/food responsibilities, and utilization of hired help.

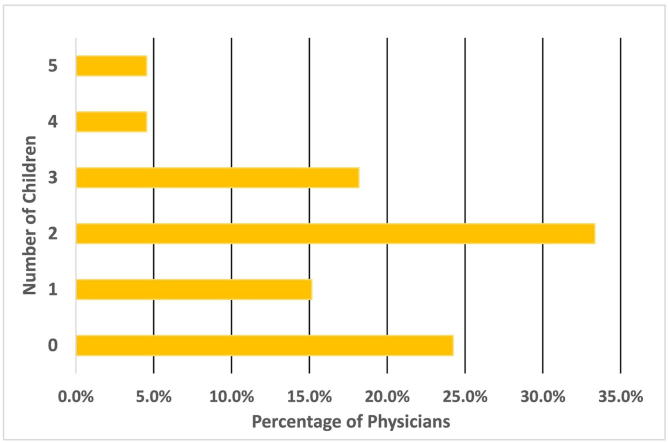

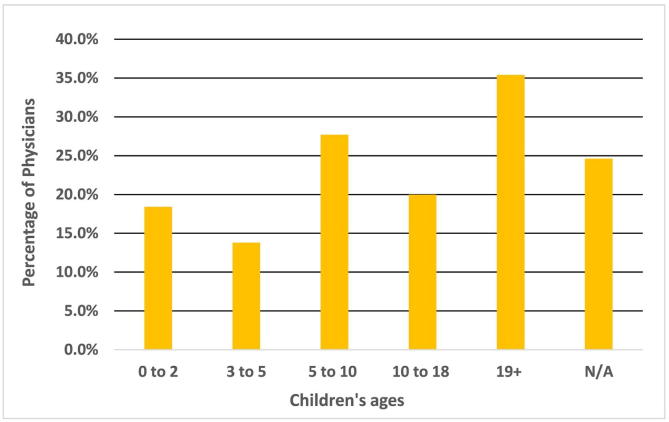

The majority of physicians surveyed have children, with two children being the most common (33%; Fig. 1). In this cohort, the largest number of physicians (35.4%) had children aged > 19 years at the present time (Fig. 2). The next largest category was children in the age group of 5 to 10 years (27.7%). With regard to child care during the day, school was the primary accommodation (31.4%) with a household employee being the second most common means of accommodation (16.5%; Table 5). Respondents most commonly reported picking their children up from school themselves (22.8%), with spouse being the second most common answer choice (18.9%). Caring for sick children at home was reported as the spouse’s responsibility in almost 20% of cases, and another family member standing in as caretaker was the second most common response.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of physicians by number of children.

Fig. 2.

Children’s ages by percentage of physicians.

Table 5.

Childcare responsibilities

| Who cares for children/dependents during the day? | Physicians, n (%) (N = 127) |

|---|---|

| Not applicable | 60 (47.2%) |

| I do | 7 (5.5%) |

| Household employee does | 21 (16.5%) |

| Spouse does | 8 (6.3%) |

| Other family member does | 8 (6.3%) |

| They are in school | 40 (31.4%) |

| They are in daycare | 13 (10.2%) |

|

Individual responses: “full time employee at home” “for 15 years, household nanny” “after-school care, then babysitter” “after-school nanny for driving them to activities” “M-F have help” |

|

| Who picks children up from school? |

Physicians, n (%) (N = 127) |

| Not applicable | 64 (50.4) |

| I do | 29 (22.8) |

| Household employee does | 21 (16.5) |

| Spouse does | 24 (18.9) |

| Other family member does | 14 (11.0) |

| Other | 2 (1.6) |

|

Individual responses: “Full time nanny” “Children ride the bus home 4-5 days a week” “Nanny” “Child can drive” |

|

| Who cares for children when they are sick? |

Physicians, n (%) (N = 67) |

| Not applicable | 36 (53.7) |

| I stay home | 9 (13.4) |

| I take them to work with me | 7 (10.4) |

| Household employee | 9 (13.4) |

| Spouse does | 13 (19.4) |

| Other family member does | 10 (14.9) |

| Other | 1 (1.5) |

|

Individual responses: “Full time household employee” “Spouse takes to work” “nanny” “back-up sitter” “They stay home alone” “all of these things at various times” |

In terms of food preparation, the majority of respondents personally cooked for their families (70.2%) and/or stated that their spouses cooked (56.7%; Table 6). Similar trends were seen for grocery shopping, with 68.5% of respondents reporting performing grocery shopping duties themselves and 44.1% reporting their spouse performing this task. Several respondents (11.7%) reported making use of online grocery services, most commonly Amazon Fresh and Instacart, either as the sole method or in conjunction with traditional grocery shopping. These services allow clients to make a shopping list, pay online, and have the groceries delivered directly to the home.

Table 6.

Grocery shopping and food preparation responsibilities

| How do you feed your family? | Physicians, n (%) (N = 67) |

|---|---|

| I cook | 47 (70.2) |

| Household employee cooks | 15 (22.4) |

| Spouse cooks | 38 (56.7) |

| Kids cook or feed themselves | 7 (10.5) |

| Eat out | 27 (40.3) |

| Food delivery service | 14 (20.9) |

| Not applicable | 4 (6.0) |

|

Individual responses: “We eat out or get take out 1 weeknight/week on average” “Family member cooks” |

|

| To obtain groceries, which services do you use? |

Physicians, n (%) (N = 127) |

| Perform shopping myself | 87 (68.5) |

| Spouse performs | 56 (44.1) |

| Employ household employee to perform | 14 (11.0) |

| Online grocery order with pickup or delivery | 32 (25.2) |

| Other | 2 (1.6) |

|

Individual responses: “Use a meal delivery service like plated or Green Chef” “Family members help with shopping” “Amazon Fresh” “Blue apron every other week” “Intermittent meal delivery service (blue apron)” “Online meal service- Hello Fresh!” “Peapod. It saves your prior orders and lets you update.” “Take out. Costco premade meals. Premade frozen dinner” “Need to use online services more often! Life changer.” |

Many survey participants reported using some form of hired help in caring for dependents, fulfilling miscellaneous household responsibilities, or running errands. The largest share of respondents indicated performing 50% of the household chores (32.3%; Table 7). There was an even split in the proportion of physicians performing either 25% or 75% of household responsibilities (25.2% each). Of those utilizing a household employee, physicians most often reported utilizing this service 1 to 8 hours per week (52.0%). The majority of physicians who participated in this survey were not the primary caretakers for an elderly parent (89.2%). The majority of physicians did utilize a household employee, most often between 1 and 8 hours per week (52.0%).

Table 7.

Household employee utilization/hired help

| Percentage of household responsibilities performed by physician | Physicians, n (%) (n = 127) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 (0.79) |

| 25 | 32 (25.2) |

| 50 | 41 (32.3) |

| 75 | 32 (25.2) |

| 100 | 20 (15.7) |

| Hours/week employing household help |

Physicians, n (%) (N = 127) |

| 0 | 15 (11.8) |

| 1-8 | 66 (52.0) |

| 9-16 | 14 (11.0) |

| 17-24 | 5 (3.9) |

| 25-32 | 5 (3.9) |

| 33-40 | 8 (6.3) |

| > 40 | 18 (14.2) |

| What services are used to simplify errands? |

Physicians, n (%) (N = 127) |

| Dry cleaning delivery | 20 (15.7) |

| Keep a reserve of back up cards and birthday presents | 48 (37.8) |

| Employee household performs | 18 (14.2) |

| Have a family member perform | 41 (32.2) |

| Use an online errand service | 12 (9.4) |

| Other | 8 (6.3) |

|

Individual responses: “No help” “Amazon” “Order online, pay bills online” “Task rabbit” “Travel agent” “Amazon prime for birthday gifts. Chewy.com for dog treats” |

Impacts on mental health and overall well-being

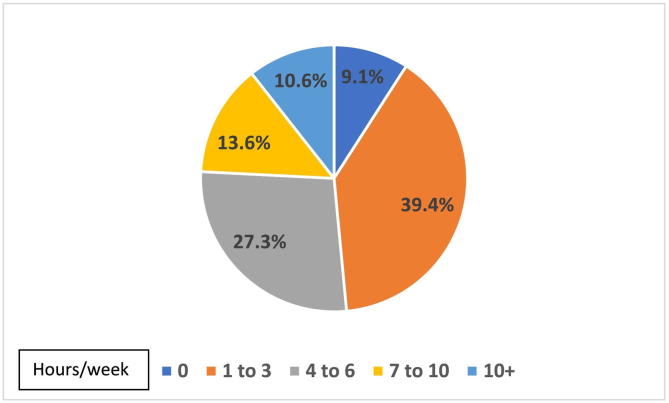

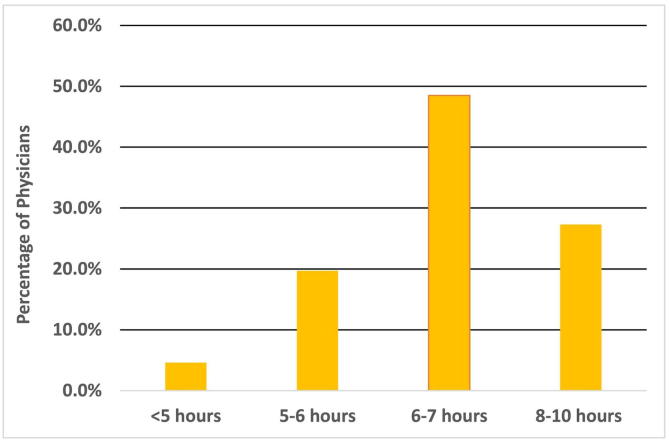

Physician overall health and well-being was assessed with three questions pertaining to the amount of personal, relaxation, and exercise time, hours of sleep per night, and overall level of stress. In terms of personal time, 1 to 3 hours of downtime was the most common answer choice (39.4%; Fig. 3). On average, nearly half of all respondents reported 6 to 7 hours of sleep per night, and approximately 25% of respondents reported getting < 6 hours of sleep per night (Fig. 4). Overall, half of physicians reported being stressed but managing their current stress levels. A third of physicians reported only occasional stressors, but 3% of physicians reported feelings of high stress and needing help with coping (Table 8).

Fig. 3.

Hours per week of personal downtime (eg, exercise, relaxation).

Fig. 4.

Average number of hours of sleep per night.

Table 8.

Mental health and overall well-being

| Overall level of stress currently | Physicians, n (%) (N = 66) |

|---|---|

| Very stressed, need help coping | 2 (3.0) |

| Stressed, but managing | 36 (54.6) |

| Overall doing fine, with just occasional stressors | 22 (33.3) |

| Minimal to no stress | 6 (9.1) |

Discussion

Several important lessons can be derived from the reported data. Female dermatologists represent a specific subset of female professionals in a high-power career setting. Women in high-powered positions, such as chief executive officer, manager, or other executive positions, are often noted to be either single, divorced, and/or childless at rates of nearly 30% in some studies (Guillaume and Pochic, 2009). However, in our cohort, 85% of physicians surveyed reported being married and only four respondents were divorced. Similarly, > 75% of survey respondents had children. These results indicate that the question of home–life and career–life balance is extremely relevant to female dermatologists because a majority of them pursue simultaneously a career and family development.

An important question that has arisen since women have entered the professional workforce in large numbers in the 20th Century has been the effect of a working mother on child development and success. Although we did not specifically ascertain the academic or developmental success of children for this cohort, the positive effects of a working mother on children has been well-defined, including superior academic performance, higher rates of employment, and greater pay (Dunifon et al., 2013, McGinn et al., 2019).

Our aim was to primarily assess the effect of maintaining a work–life balance on a physician’s sense of well-being. Forty percent of respondents in our study claimed to have only 1 to 3 hours per week for personal downtime, which included time for both relaxation and exercise. This statistic is concerning for the long-term health outcomes of the physicians in our cohort because it do not seem conducive to meeting the hours of physical activity recommended by the American Heart Association for adults. The guidelines call for at least > 2 hours per week of combination exercise in the form of cardiovascular activity (30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise for at least 5 days) and weight-bearing exercises (at least 2 days/week) to prevent atherosclerotic disease (Thompson et al., 2003).

In terms of sleep, 25% of physicians have < 6 hours of sleep per night in this cohort. The National Sleep Foundation sleep time duration guidelines recommend against young adults (i.e., age 26-64 years) having sleep duration times < 6 hours (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015). Sleeping fewer hours per night has not only been linked to serious health complications, but also impairs immune function and performance and causes a higher risk for accidents and errors and a decreased pain threshold (Watson et al., 2015).

Other interesting data points in this study include a relatively large portion of participants who utilize household employee services (91.3%), including full-time (40 +/week) help (14.2% of respondents). This would be an interesting aspect of the work–life balance to explore in this cohort. Data could be further stratified to understand the relationship between utilization of this service and physicians who hold full-time academic positions or are heavily involved in other academic activities and/or societies. Additionally, a quarter of respondents indicated using online grocery order and delivery services, either as a sole or intermittent method of obtaining groceries. Online grocery services may represent a novel timesaving approach to a time-consuming household task that was not available in the past. It will be interesting to observe whether other household tasks become outsourced to delivery and/or online services.

Spousal contributions and the importance of a supportive spouse are highlighted in this dataset. Nearly 50% of spouses contributed to grocery shopping and more than half of the spouses contributed to cooking for the household (56.7%). With regard to childrearing in this cohort, spouses of respondents were most often involved in care for a sick child. The level of involvement of spouses may suggest that the demanding career of a female physician may require a greater contribution from spouses than in families in which the mother has a more traditional role.

Limitations

This survey-based study was limited by several factors pertaining to both the demographics of our cohort and the question sets in our survey. A total of 127 individuals responded to our survey, with about half of the responses (n = 60) collected at the second, in-person administration of the survey to WDS members. Demographic information was stratified on the basis of marital status only; unfortunately, differences in age, ethnicity, and country of practice were not taken into account. The nature of the marriage type (i.e., same or opposite sex) was also not ascertained but would have provided valuable information on the types of households that exist in the field of dermatology.

All participants were drawn from a pool of members within the WDS, and this arguably represents female physicians more involved in training and mentorship with additional extraclinical responsibilities. Perhaps surveying a larger cohort of female dermatologists within the American Academy of Dermatology would allow for a greater representation of female dermatologists with various work–life schedules and obligations. Furthermore, the response rate of 8.9% is lower than desired. This precludes the drawing of significant conclusions given concerns for potential bias in responders versus nonresponders. The low response rate may have been due to the electronic nature of the survey, which was first sent to the membership at large rather than a cohort of invested and enrolled participants. However, despite the lower response rate, this work highlights the challenges faced by female dermatologists in managing a demanding career as well as household and personal duties, and how female dermatologists confront these challenges.

Due to modernization and the influence of technology on health care systems, the landscape of clinical practice has dramatically changed over the last several decades. In addition to physical time spent seeing patients, responsibilities have also extended to managing electronic health records, including charting, systematic order entries, telephone encounters, laboratory and pathology result follow up, and an open channel of communication with patients via patient portals (Rothenberger, 2017). Although work-related questions such as “how much time do you spend seeing patients?” were asked in our survey, other questions with regard to the amount of administrative time, including charting and electronic health record–related activities were not specifically asked. If these duties were added, work hours may be more accurately reflected. Looking forward, this change in cultural norms also likely affects men with working spouses, and this may be an area for future investigation.

Conclusion

Working female dermatologists must maintain a balance between a high-power career choice and advancement of personal family structure. As physicians, these individuals have challenging work demands, which include not only seeing patients, but also managing electronic health records and maintaining certification and clinically relevant knowledge through self-guided and field-mandated activities. Traditionally, childrearing and household responsibilities have been the responsibility of women, both those who working and those who do not.

The women in our cohort demonstrated multiple strategies to ease this burden, such as supportive spousal contribution, nanny and household employee services, and online, new-age errand and delivery services. However, the professional women in our cohort may be balancing work and familial obligations at the expense of their physical and mental health, with little time to exercise and fewer hours of sleep per night. Ideally, further information from additional studies on work–life balance in female dermatologists will help transform the shared experiences of these women into a systematic pool of resources, guidelines, and perhaps even workshops accessible to dermatologists in both academic and nonacademic settings.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Study Approval

The authors confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies.

Footnotes

HUMAN SUBJECTS: IRB/Ethics Committee ruled that approval was not required for this study.

References

- Butkus R., Serchen J., Moyer D.V. Achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement: A position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(10):721–723. doi: 10.7326/M17-3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrell D., Feldman R., Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among U.S. academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):269–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunifon R, Hansen AT, Nicholson S, Nielsen LP. The effect of maternal employment on children’s academic performance [Internet]. August 2013 [cited xxx]. Available from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w19364

- Guillaume C., Pochic S. What would you sacrifice? Access to top management and the work–life balance. Gend Work Organ. 2009;16:14–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshkowitz M., Whiton K., Albert S.M., Alessi C., Bruni O., DonCarlos L. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health J Natl Sleep Found. 2015;1:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.K., Kaplan S. Working toward gender diversity and inclusion in medicine: Myths and solutions. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):579–586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margosian E. Blazing the trail: Women in dermatology continue to break ground while challenges still lie ahead [Internet]. April 2017 [cited xxx]. Available from: https://www.womensderm.org/UserFiles/file/blazingthetrail_Article.pdf.

- McGinn KL, Castro MR, Lingo EL. Learning from mum: Cross-national evidence linking maternal employment and adult children’s outcomes. Work Employment Soc 2019;33(3).

- Osterweil N. Many women physicians regret delaying reproduction [Internet]. Oct 21, 2014 [cited xxx]. Available from: http://www.obgynnews.com/index.php?id=11146&cHash=071010&tx_ttnews.[tt_news]=220353

- Pichler F. Determinants of work–life balance: Shortcomings in the contemporary measurement of WLB in large-scale surveys. Soc Indic Res. 2009;92:449. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberger D.A. Physician burnout and well-being: A systematic review and framework for action. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:567–576. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt T.D., Boone S., Tan L., Dyrbye L.N., Sotile W., Satele D. Burnout and satisfaction with work–life balance among U.S. physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson P.D., Buchner D., Piña I.L., Balady G.J., Williams M.A., Marcus B.H. Exercise and physical activity in the prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:3109–3116. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000075572.40158.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson N.F., Badr M.S., Belenky G., Bliwise D.L., Buxton O.M., Buysse D. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2015;38:843–844. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wietsma A.C. Barriers to success for female physicians in academic medicine. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4 doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v4.24665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]