Highlights

-

•

Acculturation is a widely used concept in epidemiological research.

-

•

There are various ways to measure acculturation using proxies or scales; often an acculturation score is calculated.

-

•

Studies often show inconsistencies in operationalization and measurement of the concept of acculturation.

-

•

The exact outcome is often unclear; this creates a lack of comparability, generalizability and transferability of the results.

-

•

Health relevant proxies such as language skills or feeling of belonging should be measured without calculating a score.

1. Introduction

The concept of acculturation originated in North American anthropology, where it was introduced to describe the consequences of contact between the colonized and colonizing societies during colonization at the end of the 19th century (Boas, 1888; Rudmin, 2003). When the first publications using the concept appeared, no clear definition of acculturation existed. In the 1930s, anthropologists jointly decided on a definition of the concept of acculturation for future studies (Redfield, Linton, & Herskovits, 1936): Acculturation comprises “[…] phenomena which result when groups of individuals having different cultures come into continuous first-hand contact, with subsequent changes in the original cultural patterns of either or both groups”. Here, culture is understood as “[…] a set of attitudes, values, beliefs and behaviors that are shared by a group of people but differ from generation to generation” (Matsumoto, 1996).

In the 1960s, the construct was re-conceptualized to focus on an individual's experiences of changes in identity, values, and behaviors. In psychology, the best known conceptualization of acculturation is Berry's model of acculturation strategies. In this model, acculturation is assessed by two independent, orthogonal measures that address the acquisition of the new culture and the retention of the original culture. Berry distinguished four acculturation strategies: (1) marginalization (low affiliation with both cultures); (2) separation (high origin-culture affiliation, low new-culture affiliation); (3) assimilation (high new-culture affiliation, low origin-culture affiliation); and (4) integration (high affiliation with both cultures) (Berry, 1997). Although the model has been criticized for conceptual problems, such as methodological shortcomings and a lack of empirical evidence (Rudmin, 2003), it has formed the theoretical basis of numerous studies in acculturation research (Frisillo Vander Veen, 2015; Li, Kwon, Weerasinghe, Rey, & Trinh-Shevrin, 2013).

In addition to psychology, other related disciplines, such as medicine and public health (Abraido-Lanza, Armbrister, Florez, & Aguirre, 2006), have also adopted the concept, and, in the 1960s, acculturation studies became increasingly important in epidemiological research. Acculturation increasingly gained attention as an explanatory factor for health inequalities (Palinkas & Pickwell, 1995). The increasing interest regarding acculturation in research is also reflected in the publications indexed in the PubMed/MEDLINE database: Whereas only 18 publications were found with the keyword “acculturation” in 1960, almost 8,000 articles were indexed by 2018.

A number of studies have now illustrated the relationship between acculturation and health in migrant populations (Ahluwalia, Ford, Link, & Bolen, 2007; Brand et al., 2017; Carter-Pokras et al., 2008; Kim, Lee, Ahn, Bowen, & Lee, 2007; Lesser, Gasevic, & Lear, 2014; Morawa & Erim, 2014; Sussman & Truong, 2011). However, the available results show significant inconsistencies in terms of the direction and magnitude of the effects (Fox, Thayer, & Wadhwa, 2017a; 2017b) and general statements on the connection between acculturation and health therefore cannot be made (Hunt, Schneider, & Comer, 2004).

Measurements of acculturation differ in terms of dimensionality: Unidimensional scales describe acculturation as a linear continuum ranging from “unacculturated” to “acculturated,” and acculturation is seen as a linear process of moving from the original culture to the new culture (Gordon, 1964). In contrast, bidimensional scales are based on the idea that it is possible for an immigrant to acquire elements of the new culture without losing his or her original culture (Berry, 1997). In these scales, acculturation is described as two processes that coexist in two different dimensions (Sam, 2006). Here, two independent scales measure the degree to which the original culture is maintained and the extent to which the culture of the country of immigration is adopted (Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009). Multidimensional scales go even further and propose that acculturation can consist of three or more intersecting cultural streams. These scales attempt to capture acculturation as a complex process by examining its multiple dimensions individually (Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009).

Global migration and the associated interplay of cultural, biological, psychological, economic, and social factors make an important contribution to explaining health inequalities (Malmusi, Borrell, & Benach, 2010). Differences in the understanding of illness, health behavior, access to health services, and the use of medical, preventive, and health-promoting services are shaped by various aspects, such as structural barriers, culture, and social exclusion; these differences can have an impact on the prevalence and incidence of various diseases as well as on mortality rates (Brause, Reutin, Schott, & Yilmaz-Aslan, 2010; Davies, Basten, & Frattini, 2009; Keller, 2004; Razum et al., 2008; Rodewig, 2000; Scheppers, van Dongen, Dekker, Geertzen, & Dekker, 2006).

Thus far in Germany, data to explain these associations regarding people with a migration history are lacking. This is partially due to the insufficient inclusion of people with a migration history into the national health monitoring of the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), the federal public health institute in Germany. In addition, relevant concepts to describe associations between migration and health inequalities within the surveys are lacking. It is important to identify migration-specific resources, exposures and determinants, experiences and needs to address them within the framework of health surveys (Santos-Hövener et al., 2019). An important concept in this context appears to be the concept of acculturation, which, despite its frequent application in epidemiologic studies, has not been included in RKI surveys. In order to examine the potential of this concept for health surveys, we conducted a systematic literature review with the following objectives: (1) to determine the extent to which acculturation has been used so far in epidemiological research on migrant populations; (2) to evaluate how the construct has been measured in epidemiological research; and (3) to derive recommendations for application and the operationalization of the concept acculturation in prospective health research.

2. Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature research in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines for systematic literature reviews (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). The study protocol of the review can be viewed online (Schumann et al., 2018). Relevant articles, which included the search term “acculturation” in the title, were identified using an a priori defined search string in the MEDLINE/PubMed, SCOPUS, and ScienceDirect databases. All searches took place on May 16, 2017. An overview of the search terms can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the search terms.

| #1 Acculturation | #2 Migration | #3 Method | #4 Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acculturaion | Migration | Method | Health |

| Immigration | Methods | Epidemiological | |

| Migrant | Studies | Epidemiology | |

| Migrate | Study | ||

| Migrants | Scale | ||

| Immigrant | Measure | ||

| Immigrants | Measurement | ||

| Immigrate | Measurements | ||

| Minority | Measured | ||

| Minorities | Measuring | ||

| Research | |||

| Researching | |||

| Survey | |||

| Surveys | |||

| Surveying | |||

| Test | |||

| Testing | |||

| Investigation | |||

| Investigate | |||

| Investigating | |||

| Questionning | |||

| Questionnaire | |||

| Assessment | |||

| Assess | |||

| Assessing | |||

| Analyze | |||

| Analyze | |||

| Analysis | |||

| Analysis | |||

| Analysing | |||

| Analyzing |

Search combination: #1 (title) AND #2 (title and/or abstract) AND #3 (title and/or abstract) AND #4 (title and/or abstract).

Selection criteria

The search included all publications that (1) were published in English or German; (2) had samples that included adults aged 18 years or older (exception: population-based surveys focusing on adults with samples that included people aged 15 years or older were also included); (3) used, operationalized, and/or measured the concept of acculturation; (4) had a clear epidemiological orientation; and (5) investigated the direct influence, rather than the indirect influence (e.g., the influence of mother's acculturation) of acculturation on the study participant.

We categorized the identified publications according to study approach as (1) quantitative studies; (2) reviews or overviews; (3) theoretical discourses; (4) qualitative studies; or (5) mixed-method studies. Considering the objectives of the review, only publications reporting quantitative studies were included in the full-text analysis.

Data collection and analysis

Title and abstract screening was conducted independently by two researchers. Full-text analysis and coding were carried out by four researchers. In addition to a detailed manual for screening and coding the articles, a training course provided the basis for the data analyses and possible ambiguities were discussed in a group. The results were summarized in tables.

Coding general study characteristics and the use of acculturation

The data synthesis was carried out by extracting general information about each study (authors, publication year, title, and country), study characteristics (population-based health survey [yes/no], survey name, and sample size), sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants (age, gender, and targeted migrant populations/ethnicities), health outcomes under investigation, presence of a definition of acculturation (yes [definition or acculturation model discussed], no [the meaning of acculturation is only briefly described], or no answer [no theoretical embedding]), and the acculturation measures used (proxy, scale, or both).

Coding of acculturation proxies

The proxies used to measure acculturation were initially recorded in their original wording. Subsequently, consistent codes were administered to summarize similar concepts in these proxies, and four overarching domains were identified: (1) language; (2) migration history; (3) ethnicity/race; and (4) social environment/culture.

Coding of acculturation scales

Each identified acculturation scale was coded for the number of studies where the scale was used and the targeted migrant populations/ethnic groups. For all scales that were used at least five times, the following variables were added: year of development, dimensionality (uni-, bi-, or multidimensional), use of a theoretical framework (yes [definition or model for acculturation included], no [the meaning of acculturation is only briefly described], or no answer [no theoretical embedding]), number of items, domains, and the reliability (Cronbach's alpha) and validity of the scale.

3. Results

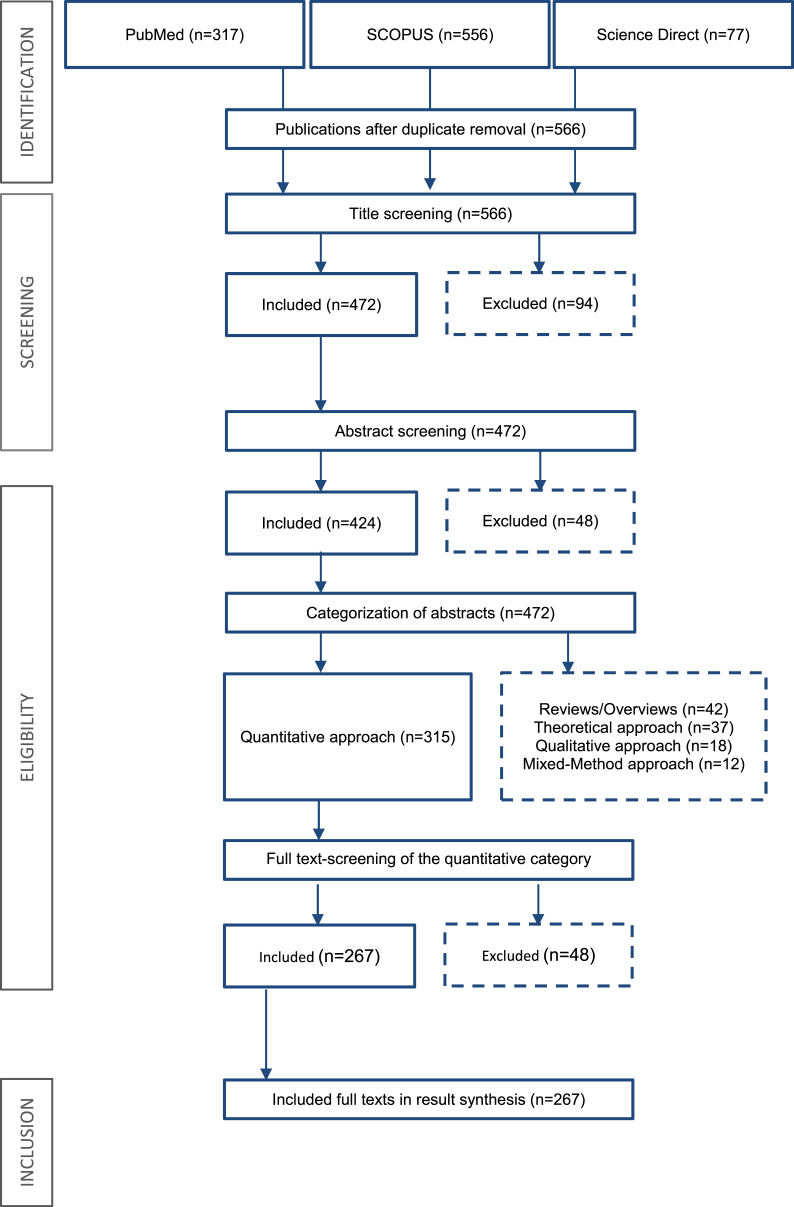

The search identified 950 publications. After duplicates were excluded, a total of 566 publications were identified according to the search strategy. During the title and abstract screening, 424 publications were found to meet the inclusion criteria. These publications were published from 1976 to 2017, the number of studies increased over time.

Acculturation was measured most frequently in quantitative health studies (n = 267, 74.3%). However, we also found reviews or overviews (n = 42, 9.9%) and publications with theoretical discourses (n = 37, 8.7%) in which acculturation was referenced. A total of 4.2% of the studies were qualitative (n = 18), and 2.8% were mixed-method studies (n = 12). Fig. 1 shows the resulting PRISMA diagram.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA- diagram.

Study characteristics and the use of the concept of acculturation

Of the 267 included publications, about half were population-based health surveys (n = 132, 49.4%). The other studies (n = 135, 50.6%) were smaller health surveys, for example studies using a convenience or a snowball sampling procedure, case–control studies, or intervention studies. The majority of the studies came from majority English-speaking countries. Another 29 studies (10.9%) were conducted in Europe (Table 2). Many of the studies referred to Asian Americans (n = 129, 43.4%) or Hispanics (n = 95, 32.0%). The other studies focused on American (n = 19, 6.5%), African (n = 17, 5.7%), European (n = 10, 3.4%), or Caribbean (n = 9, 3.0%) migrants. Nine studies (3.0%) covered a wide range of migrant populations and ethnicities worldwide, and a further nine studies (3.0%) did not provide any information on the targeted migrant population.

Table 2.

Study country (n = 267).

| Country | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 206 | 77.2 |

| Canada | 11 | 4.1 |

| Germany | 9 | 3.4 |

| Netherlands | 9 | 3.4 |

| Australia | 7 | 2.6 |

| South Korea | 4 | 1.5 |

| Sweden | 4 | 1.5 |

| Israel | 2 | 0.7 |

| China | 2 | 0.7 |

| Greece | 2 | 0.7 |

| Chile | 1 | 0.4 |

| India | 1 | 0.4 |

| Singapore | 1 | 0.4 |

| Taiwan | 1 | 0.4 |

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 0.4 |

| Ghana | 1 | 0.4 |

| Luxembourg | 1 | 0.4 |

| Finland | 1 | 0.4 |

| Switzerland | 1 | 0.4 |

| Norway | 1 | 0.4 |

| Denmark |

1 |

0.4 |

| Total | 267 | 100.0 |

With regard to health outcomes, most of the studies focused on mental health (n = 95, 27.7%), physical health (n = 83, 24.2%), or health behavior (n = 90, 26.2%). Other topics covered were general health status (n = 15, 4.4%), utilization of medical care (n = 26, 7.6%), sexual and reproductive health (n = 11, 3.2%), prevention and health promotion (n = 12, 3.5%), health literacy (n = 8, 2.3%), and mortality (n = 3, 0.9%).

A total of 147 of the included publications (55.1%) provided a definition of acculturation, whereas 102 publications (38.2%) only stated that acculturation is an important concept in the analysis of migrant health and 18 (6.7%) contained neither a definition nor an attribution of the meaning of acculturation.

Measurement of acculturation

Of the included publications (n = 267), some measured acculturation with specific instruments, such as scales (n = 124, 46.4%), proxies (n = 115, 43.1%), or both methods (n = 28, 10.5%). The 132 identified population-based health surveys used proxies more frequently (n = 82, 62.1%) than scales (n = 36, 27.3%). For the 135 smaller health surveys identified, proxies were used less frequently (n = 33, 24.5%) than scales (n = 88, 65.1%). A combined approach (acculturation instruments supplemented by proxy measurements) was used in some population-based health surveys (n = 14, 10.6%) and smaller health surveys (n = 14, 10.4%).

Proxies used in epidemiological research

A total of 33 proxies were identified and categorized into four overarching domains: (1) language (n = 14); (2) migration history (n = 11); (3) ethnicity/race (n = 4); and (4) social environment/culture (n = 4). Table 3 shows the identified proxies in these domains. The most frequently used proxies were those on migration history (n = 225, 84.3%), particularly the length of stay in the host country, the respondent's country of birth, and the country of birth of the respondent's parents. Proxies on language were also frequently used (n = 168, 38.5%). Self-assessment of language skills, selected survey language, and the use of language at home were the most commonly included variables. Several studies (n = 32, 6.0%) used proxies regarding ethnicity/race, including self-reported ethnicity and the feeling of belonging to the home country or the destination country. Proxies for social environment/culture were used less frequently (n = 11, 2.5%) and included measurements of social network, neighborhood, and cultural practices.

Table 3.

Identified proxies by dimension (n = 267).

| Dimension | Proxies | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migration history | 225 | 51.6 | |

| Length of stay in host country | 89 | 20.4 | |

| Country of birth | 78 | 17.9 | |

| Parents' countries of birth | 16 | 3.7 | |

| Nationality | 14 | 3.2 | |

| Age at immigration | 11 | 2.5 | |

| Proportion of life in the country of immigration | 6 | 1.4 | |

| Number of years of education in the country of immigration | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Grandparents' countries of birth | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Generation status | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Number of years since migration | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Resident status |

2 |

0.5 |

|

| Language | 168 | 38.5 | |

| Self-assessment of language skills | 32 | 7.3 | |

| Language chosen to answer the questionnaire or the interview | 30 | 6.9 | |

| Use of language at home | 26 | 6.0 | |

| Use of language in media/TV/radio | 23 | 5.3 | |

| Use of language with friends | 15 | 3.4 | |

| General language use | 11 | 2.5 | |

| Use of language as child | 7 | 1.6 | |

| Preferred language | 6 | 1.4 | |

| Use of language in thought | 6 | 1.4 | |

| First language | 5 | 1.1 | |

| External assessment of language skills | 4 | 0.9 | |

| General language skills | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Language barriers | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Mother tongue |

1 |

0.2 |

|

| Ethnicity/Race | 32 | 6.0 | |

| Ethnicity | 12 | 2.8 | |

| Feeling of belonging to the home country | 9 | 2.1 | |

| Feeling of belonging to the country of immigration | 9 | 2.1 | |

| Race |

2 |

0.5 |

|

| Social environment/culture | 11 | 2.5 | |

| Social network | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Neighborhood | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Cultural practice | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Attitude to traditional values | 1 | 0.2 |

Scales used in epidemiological research

A total of 57 different scales were identified. The most commonly used unidimensional scales were the Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIA) (Suinn, Ahuna, & Khoo, 1992) and the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH) (Marin, Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, & Perez-Stable, 1987). Frequently used bidimensional scales were the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale (BAS) (Marin & Gamba, 1996) and the Lowlands Acculturation Scale (LAS) (Mooren, Knipscheer, Kamperman, Kleber, & Komproe, 2001). The Acculturation Scale for Mexican Americans II (ARSMA-II) is an example of a multidimensional scale (Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995). The six most commonly used scales are briefly explained in more detail below (see also Table 4).

Table 4.

Acculturation scales.

| Authors | Scale | Dimensionality | Theory/model | n | Number of items | Domains | Reliability (Cronbach's alpha) | Validity | Targeted migrant population(s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suinn et al. (1992) (Suinn et al., 1992) | Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIA) | Unidimensional | No | 16 | 21 | Language, identity, friendships, behaviors, generational/geographic background, and attitudes | 0.91 | Total years attending school in the U.S. (0.61), years living in the U.S. (0.56), years lived in a non-Asian-neighborhood (0.41), self-rating of acculturation (0.62), age upon attending school in the U.S. (−0.60), and age upon arriving in the U.S. (−0.49). | Asian Americans | |||||

| Marin et al. (1987) (Marin et al., 1987) | Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH) | Unidimensional | No | 15 | 12 | Language use, media, ethnic social relations | 0.92 | Generation (0.65), length of residence in the U.S. (0.70), self-evaluation of their level of acculturation (0.76), acculturative index (0.83), and age of arrival in the U.S. (−0.69) | Hispanics (Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, “other Hispanics” like Central Americans, and Puerto Ricans) | |||||

|

Cuellar et al. (1995) (Cuellar et al., 1995) |

Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-Americans II (ARSMA-II) |

Multidimensional |

Yes |

12 |

AOS: 13 MOS: 17 MAR: 18 |

Language use, language preference, ethnic identity and classification, cultural heritage, ethnic behaviour, ethnic interaction |

Anglo Orientation Scale [AOS]: 0.83 Mexican Orientation Scale [MOS]: 0.88 Marginality: 0.87 |

Generational status (0.61), Linearly derived acculturation score from ARSMA-II and ARSMA (0.89) |

Mexican Americans |

|||||

| Authors |

Scale |

Dimensionality |

Theory/model |

n |

Number of items |

Domains |

Reliability (Cronbach's alpha) |

Validity |

Targeted migrant population(s) |

|||||

| Marin and Gamba (1996) (Marin & Gamba, 1996) | Bidimensional Acculturation Scale (BAS) | Bidimensional | No | 8 | 24, short version: 12 | General language use, linguistic proficiency, electronic media | Hispanic dimension: 0.90 Non-Hispanic dimension: 0.96 |

Hispanic dimension: Generation (−0.42), length of residence in the U.S. (−0.28), age at arrival (0.41), proportion of life in the U.S. (−0.17), education (−0.29), self-identification (−0.38), SASH (−0.64) Non-Hispanic dimension: Generation (0.50), length of residence in the U.S. (0.46), age at arrival (−0.60), proportion of life in the U.S. (0.41), education (0.59), self-identification (0.47), SASH (0.79) |

Hispanics (Central Americans, Mexican Americans) | |||||

|

Stephenson (2000) (Stephenson, 2000) |

Stephenson's Multigroup Acculturation Scale (SMAS) |

Bidimensional |

Yes |

6 |

32 |

Language, interaction, media and food; within these domains: knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes (Immersion in dominant society (DSI), immersion in one's ethnic society(ESI)) |

First study: Whole scale: 0.86; DSI: 0.90; ESI: 0.97 Second study: DSI: 0.75; ESI: 0.94 |

First study: generational status and DSI, ESI Second study: ESI positively correlated with MOS (ARSMA-II) and negatively correlated with AOS (ARSMA-II); ESI positively correlated with the Hispanic Domain scale (BAS) and negatively correlated with the Non-Hispanic Domain scale (BAS) DSI positively correlated with the AOS (ARSMA-II); DSI positively correlated to the Non-Hispanic scale (BAS) |

Various ethnic backgrounds |

|||||

|

Authors |

Scale |

Dimensionality |

Theory/model |

n |

Number of items |

Domains |

Reliability (Cronbach's alpha) |

Validity |

Targeted migrant population(s) |

|||||

| Mooren et al. (2001) (Mooren et al., 2001) | Lowlands Acculturation Scale (LAS) | Bidimensional | Yes | 5 | 25 | Traditions, Norms and values, Loss, Skills, Social integration | Traditions: 0.62, Norms and values: 0.60, Loss: 0.77, Skills: 0.74, Social integration: 0.54 (Fassaert et al., 2009) | Sex, age, length of stay in the Netherlands, attendance of mental health care | Various ethnic backgrounds | |||||

Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIA)

Of the 267 included studies, 16 (6.0%) used the SL-ASIA. Published in 1992 by Suinn et al. (Suinn et al., 1992), the scale was intended for use among Asian Americans. It is a linear, unidimensional scale with 21 items covering language, identity, friendship, behaviors, generational/geographic background, and attitudes. Internal reliability testing found an alpha coefficient of 0.91 among 324 Asian American university students in Colorado, with useable data from 284 subjects (Suinn et al., 1992).

Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH)

A total of 15 included studies (5.6%) used the SASH. The scale was developed by Marin et al. (1987) for use among Hispanic populations. This scale is unidimensional and includes 12 items that assess language use, media use, and ethnic social relations. The study population for validation of the SASH consisted of 363 Hispanics (44% Mexican Americans, 6% Cuban Americans, 47% “other Hispanics” such as Central Americans, and 2% Puerto Ricans) and 228 non-Hispanic whites. The alpha coefficient was 0.92.

Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans II

The ARSMA-II was used in 12 included studies (4.5%). This scale is a revised version of the original ARSMA scale (Cuellar, Harris, & Jasso, 1980), developed by Cuellar et al. (1995) for use among Mexican Americans. The ARSMA-II is multidimensional and measures three different dimensions of acculturation, using the Mexican Orientation Scale (MOS), the Anglo Orientation Scale (AOS), and the Marginality Scale (MAR). The ARSMA-II can also produce bidimensional results using only the MOS and AOS dimensions. It evaluates the levels of assimilation or separation independently for each dimension. Each dimension covers language use, language preference, ethnic identity and classification, cultural heritage, ethnic behavior, and ethnic interaction. Values of Cronbach's alpha coefficient were 0.88 for the MOS, 0.83 for the AOS, and 0.87 for the MAR (Cuellar et al., 1995).

Bidimensional Acculturation Scale (BAS)

A total of eight included studies (3.0%) used the BAS. Developed by Marin and Gamba (1996), the BAS is a scale for use among Hispanic populations. It is a bidimensional scale consisting of 24 items in the long version and 12 items in the short version. These items assess general language use, linguistic proficiency, and preferred language in electronic media (i.e., television and radio). The scale measures the extent to which respondents participate in the origin culture and in the host culture. Development and testing occurred with 254 Hispanics in San Francisco, California. The majority of the sample was born in Central America (52.8%) or Mexico (24.0%). Reliability testing found alpha coefficients of 0.90 for the Hispanic dimension and 0.96 for the non-Hispanic dimension (Marin & Gamba, 1996).

Stephenson's Multigroup Acculturation Scale (SMAS)

Stephenson's Multigroup Acculturation Scale was used six times in the included studies (2.3%). The scale was developed by Stephenson in 2000 and can be used across different migrant groups (Stephenson, 2000). It is a bidimensional scale that includes 32 items. Of these, 15 items measure the dominant society immersion (DSI) and a further 17 items measure the immersion in one's ethnic society (ESI). Within both dimensions, language, interaction, media, and food are assessed, and each domain reflects knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes. Reliability (Cronbach's alpha) was 0.86 for the total scale and 0.97 and 0.90 for ESI and DSI respectively (Stephenson, 2000).

Lowlands Acculturation Scale (LAS)

The LAS was used five times in the included studies (1.9%). This scale was developed by Mooren et al. (2001), who were inspired by the Demands of Immigration Scale (DIS), (Aroian, Norris, Tran, & Schappler-Morris, 1998), the work of Berry and colleagues, and the change in moral attitudes over time described among Wallachians and Macedonians by Schierup and Alunnd (1987). The LAS is applicable to people with various ethnic backgrounds living in the Netherlands, such as Turkish people, Surinamese people (both Creole and Hindu backgrounds), and Moroccans. It is a bidimensional scale with a total of 25 items across five subscales: values and norms, social integration, traditions, skills, and loss. One analysis showed that removing Item 23 (“I believe Dutch women can make their own decisions in life”; values and norms subscale) increased the internal consistency of that subscale. After removing that item, the Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the subscales were 0.54 (social integration), 0.60 (values and norms), 0.62 (traditions), 0.74 (skills), and 0.77 (loss) (Fassaert et al., 2009).

4. Discussion

This review has shown that the concept of acculturation has been widely used in epidemiological research since the 1960s. We were able to identify a total of 566 publications that applied the concept in quantitative or qualitative studies, discussed its theoretical background and/or examined the connection between different health outcomes and acculturation.

The analysis of the quantitative studies showed that the majority were conducted in the United States and primarily investigated the connection between the acculturation of specific migrant populations or ethnic groups (especially Asian Americans and Hispanics) and various health outcomes.

Lack of definition and theoretical embedding of acculturation in epidemiological research

Approximately half of the included studies provided a definition or theoretical classification of the concept of acculturation. As already indicated by Thomson and Hoffman-Goetz (2009, p. 989), “[…] public health researchers [should] provide a clear statement of the interpretation and use of acculturation” and “[…] it may not always be clear what researchers hope to measure even within, let alone between, studies.”

Considering the lack of a definitional and theoretical basis, multiple content-related and methodological challenges need to be addressed. These include inconsistencies in operationalization and measurement of the concept of acculturation and a lack of comparability, generalisability, and transferability of the results. The root of these inconsistencies lies, above all, in the multiple ways that acculturation has been conceptualized and operationalized, but also in the lack of extension of the construct with regard to epidemiological questions. The disciplinary transition from anthropology to epidemiology and related disciplines took place without refining the construct or its measures for health research (Hunt et al., 2004), (Lopez-Class, Castro, & Ramirez, 2011).

Inconsistencies in operationalization and measurement of acculturation in epidemiological research

The operationalization and measurement of acculturation in epidemiological research varied greatly among the quantitative studies. In principle, proxy/single item measurements can be distinguished from measurements that are based on scales measuring acculturation.

The reviewed studies used numerous proxy variables. Measurements using proxies are time efficient and convenient, but they also carry a risk of incorrectly mapping behavior and attitudes (Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009). According to Thomson and Hoffman-Goetz (2009), proxies often measure phenomena that “[…] may or may not be associated with acculturation” (p.989) (p. 989) (p. 989) (p. 989). For example, the proxy of language, used as an indicator of cultural practices, is actually seen as an indicator of cultural adaption (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). However, Schwartz, Zamboanga, and Jarvis (2007) also reported that many Hispanic adolescents who spoke either little or no Spanish nevertheless identified very strongly with their Hispanic ethnic identity. This shows again the complexity of belonging that is multidimensional in itself. Evidently, single proxies such as language proficiency are not sufficient to address these questions.

This review also identified a wide range of acculturation scales. Some of these scales (e.g., the LAS) have been used in various migrant groups, whereas others (e.g., the SASH) were developed for use in specific migrant groups. It is evident that the health outcomes, considered in the studies that used these scales, vary widely from physical health (Irvin et al., 2013) to health behaviour (Kane et al., 2016). However, it remains unclear whether they have been tested for quality criteria such as reliability and validity.

When comparing single items within the scales to the proxies used in the reviewed studies, it is noticeable that they often attempt to measure similar or identical aspects. We identified four global thematic domains that can be used to summarize and describe single items and scales used in acculturation research: (1) migration history; (2) language; (3) ethnicity/race; and (4) social environment/culture. The main difference between proxies and scales is that acculturation scales are used to calculate an acculturation score across different domains. However, some of these scales form an acculturation score covering only one domain. The purpose of an acculturation score is to make statements about a person's degree of acculturation. In this context, however, questions arise regarding the interrelation of the analysed acculturation domains and whether changes in one domain also entail changes in the others. Also, factors moderating or mediating the effects within or between domains should also be elucidated (Fox et al., 2017a; Schwartz et al., 2010).

According to Schwartz et al. (2010), however, attempting to describe a person as acculturated or not acculturated is an “oversimplification of a complex phenomenon”. Often the specification of relevant social interactions and components of cultural identity are missing such as “practices, values, and identifications of the heritage culture as well as those of the receiving culture” (Schwartz et al., 2010). Thus, even if these components are well specified and acculturation is being discussed as a complex multidimensional process, the basic assumption underlying the concept itself remains a “movement” of persons or groups between two cultures—the host culture and the culture of origin. This view of culture being a fixed category consisting of randomly and subjectively chosen social practices seems obsolete and is not capable of reflecting the diversity of modern, increasingly heterogeneous societies and “hybrid” identities (Hall, 2000; Rudmin, 2003).

Problems with comparability, generalisability, and transferability in quantitative studies in epidemiological research

Varying approaches to defining, operationalizing, and measuring acculturation also lead to difficulties regarding comparability, generalisability, and transferability of the results of quantitative studies in epidemiological research (Carter-Pokras et al., 2008). Comprehensive statements on acculturation and particular outcomes are difficult because of the ambiguity of the results of different studies, for example, on the connection between acculturation and smoking (Sussman & Truong, 2011) or obesity (Creighton, Goldman, Pebley, & Chung, 2012).

This also applies to the transferability of results: Although it has been shown that the patterns and correlates of acculturation processes tend to be comparable across receiving countries (Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006), some exceptions and discrepancies have also been observed (Jasinskaja-Lahti, Liebkind, Horenczyk, & Schmitz, 2003). Therefore, caution should be exercised when it comes to transferring associations discovered in studies conducted in the United States, for example, to other countries and other migrant populations (Schwartz et al., 2010). To understand and compare migration-related effects within and across countries and distinct population subgroups, the specific historical, social, and political situation of the respective country should be taken into account when interpreting associations between health outcomes and acculturation (Schwartz et al., 2010).

“One size fits all?“— disregarding diversity

The present review has shown that there is a risk of stereotyping when applying the concept of acculturation. Hunt et al. (2004, p. 973) have previously noted that “[…] acculturation as a variable in health research may be based more on ethnic stereotypes than on objective representation of cultural differences.” People are assigned to certain categories or groups on the basis of external ascriptions (e.g., ethnicity or nativity), and it is assumed that they share the same cultural practices, values, and customs, as well as a common cultural identity, because of these characteristics (Phinney, 1996).

An illustrative example of this point is the focus of epidemiological studies conducted in the United States on the ethnic group of so-called “Hispanics.” This term was introduced in the United States Census to refer to migrants of Latin American origin, grouping together migrants from 21 countries and classifying them as a supposedly homogeneous group, neglecting the cultural and social differences within the group (Hunt et al., 2004; Schwartz et al., 2010; Suárez-Orozco & Páez, 2002). This illustrates the particular problem of categorization, which requires special awareness due to the risks of generalization, stereotyping, and stigmatization (Chirkov, 2009; Rudmin, 2003; Schwartz et al., 2010).

Migrants face multiple types and degrees of social challenges, depending on their origin, ethnic or social identity, age, circumstances and reasons of migration, legal status, access to education and health care, and the labor market in the country of origin and the new country (Zane & Mak, 2003). In addition to individual factors, contextual and structural factors constituting the processes of inclusion, and social participation should be taken into account when aiming to analyze the interplay between acculturation and health (Alegria, Sribney, Woo, Torres, & Guarnaccia, 2007; Steiner, 2009). As such, stigmatization and discrimination, as well as the effects of structural and institutional exclusion, should be considered as relevant health determinants. These concepts are known to be crucial causes of the separation of ethnic minorities from the society and of the formation of so-called “reactive ethnicities” – processes that are highly interconnected with multiple health outcomes (Rumbaut, 2008).

There is also a need for the revision of the terminology used in research that applies the concept of acculturation, such as “host” or “culture of origin” and the “mainstream” or “new” culture (Hunt et al., 2004). Acculturation is often pursued as an adjustment of minority populations to move toward a majority population of a country; to put it pointedly, this perception of acculturation implicates an unidirectional adjustment to a dominant culture. Additionally, research on acculturation and its effects rarely addresses the effects and conditions within dominant populations of respective countries (Rudmin, Wang, & Castro, 2016).

Recommendations for health surveys

Our results induced fundamental doubts in the necessity and utility of a search for a suitable and recommendable instrument for measuring acculturation in prospective health surveys. As described above, we found substantial ambiguities in the definitions and theoretical bases associated with the concept itself, as well as a lack of uniform operationalization and validated measurements. Finally, calculating an acculturation score to make statements about a person's degree of acculturation also appears to be very limited with regard to the complexity of the social processes behind it.

Therefore, an implementation of single migration-specific items within the discussed domains of acculturation such as migration history, language, ethnicity/race, and social environment/culture appears to be more suitable than an application of the concept “acculturation” in the aggregate. The credibility of using an acculturation score is questionable considering that it is not possible to summarize such complex social factors into one numeric result. Instead, specific approaches are required to address the effects of these single domains as well as included items and to explain differences in physical and mental health, health behavior, access to health care, and the use of preventive and health-promotion services among migrants.

General conclusions

Concepts used in the research on migration and health require continuous reflection and evolution. Research is inevitably influenced by values, views, experiences and knowledge of the involved researchers, this issue of positionality has to be considered when discussing concepts such as acculturation. (Qin, 2016, pp. 1–2; Sanchez, 2010). The potential risks of one-sidedness in research on migrants need to be anticipated - such as potential stereotyping, blaming and stigmatization. For this aim, an involvement of multiple perspectives and participation of persons or groups as the research subject – in this case migrants/persons with their own migration history – might be a useful approach to achieve a possibly comprehensive framing (Bach, Jordan, Hartung, Santos-Hövener, & Wright, 2017; Leung, Yen, & Minkler, 2004; Robert Koch-Institut, 2017).

Finally, further aspects should be considered in addition to the domains identified here. These include discrimination, socioeconomic status, and barriers to health care, which are some of the most relevant aspects in the analysis of various health outcomes in specific migrant populations (Abraido-Lanza et al., 2006; Hunt et al., 2004; Malcarne, Chavira, Fernandez, & Liu, 2006; Moyerman & Forman, 1992; Padilla, 1980; Richman, Gaviria, Flaherty, Birz, & Wintrob, 1987; Rudmin, 2009; Sheldon & Parker, 1992).

Limitations

There are several limitations to be mentioned. First, the word “acculturation” was included in the search string with a restriction: To obtain precise results, only publications that had the term in their titles were identified. In addition, only publications in German or English were considered because of the researchers’ language skills. Furthermore, articles that were missing because full texts could not be retrieved could have resulted in bias. However, this is probably not the case because only three articles were unavailable for the review (<1.0%). To enable a peer review procedure, several researchers were involved in the systematic review, and, to minimize sources of error, a manual was prepared for the screening procedure, training was provided, and ambiguities were discussed in regular meetings. Finally, it should be noted that detailed evaluations were carried out only for quantitative studies.

5. Conclusion

Acculturation is a complex concept that has recently gained increasing attention in the field of epidemiology. This review shows that the concept of acculturation has been applied in multiple studies on various health outcomes and migrant populations or ethnic groups. Nevertheless, many uncertainties remain with regard to the definition and understanding of what acculturation actually means. There are pronounced inconsistencies in the operationalization and measurement of the concept, and the risks of stigmatization and discrimination are high. Further research is necessary to investigate the relevant migration-specific aspects that can contribute to explaining health inequalities. However, building a score that summarizes various personal, contextual, and structural factors and aims to capture a person's degree of acculturation seems obsolete. There is a crucial need for a differentiated and multifaceted approach that can do justice to the diversity and heterogeneity of modern societies.

Financial disclosure statement

There are no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics approval

No ethical approval was required since only previously published data were analysed in the systematic review.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maria Schumann: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Marleen Bug: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. Katja Kajikhina: Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Carmen Koschollek: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Susanne Bartig: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Thomas Lampert: Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Claudia Santos-Hövener: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the German Ministry of Health. The funding was granted to the Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, dated July 20, 2016 for the study "IMIRA (Improving Health Monitoring in Migrant Populations)”. Project lead: Dr. Claudia Santos-Hövener, Grant number: ZMVI1-2516FSB408. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Abraido-Lanza A.F., Armbrister A.N., Florez K.R., Aguirre A.N. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(8):1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia I.B., Ford E.S., Link M., Bolen J.C. Acculturation, weight, and weight-related behaviors among Mexican Americans in the United States. Ethnicity & Disease. 2007;17(4):643–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M., Sribney W., Woo M., Torres M., Guarnaccia P. Looking beyond nativity: The relation of age of immigration, length of residence, and birth cohorts to the risk of onset of psychiatric disorders for Latinos. Research in Human Development. 2007;4(1):19–47. doi: 10.1080/15427600701480980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian K.J., Norris A.E., Tran T.V., Schappler-Morris N. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Demands of immigration scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 1998;6(2):175–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach M., Jordan S., Hartung S., Santos-Hövener C., Wright M.T. Participatory epidemiology: The contribution of participatory research to epidemiology. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology. 2017;14:2. doi: 10.1186/s12982-017-0056-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J.W. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 1997;46(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J.W., Phinney J.S., Sam D.L., Vedder P. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ, US: 2006. Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. [Google Scholar]

- Boas F. The aims of ethnology. In: Boas F., editor. Vols. 628–638. Macmillan; New York: 1888. (Race, language and culture). [Google Scholar]

- Brand T., Samkange-Zeeb F., Ellert U., Keil T., Krist L., Dragano N.…Zeeb H. Acculturation and health-related quality of life: Results from the German national cohort migrant feasibility study. International Journal of Public Health. 2017;62(5):521–529. doi: 10.1007/s00038-017-0957-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brause M., Reutin B., Schott T., Yilmaz-Aslan Y. Migration und gesundheitliche Ungleichheit in der Rehabilitation - Versorgungsbedarf und subjektive Bedürfnisse türkischer und türkischstämmiger Migrant(inn)en im System der medizinischen Rehabilitation. Bielefeld: Universität Bielefeld - Fakultät für Gesundheitswissenschaften. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Pokras O., Zambrana R.E., Yankelvich G., Estrada M., Castillo-Salgado C., Ortega A.N. Health status of Mexican-origin persons: Do proxy measures of acculturation advance our understanding of health disparities? Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2008;10(6):475–488. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirkov V. Summary of the criticism and of the potential ways to improve acculturation psychology. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2009;33(2):177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton M.J., Goldman N., Pebley A.R., Chung C.Y. Durational and generational differences in Mexican immigrant obesity: Is acculturation the explanation? Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75(2):300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I., Arnold B., Maldonado R. Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17(3):275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I., Harris L.C., Jasso R. An acculturation scale for Mexican American normal and clinical populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1980 [Google Scholar]

- Davies A., Basten A., Frattini C. 2009. Migration: A social determinant of the health of migrants. Background paper developed within the framework of the IOM project "assisting Migrants and communities (AMAC): Analysis of social determinants of health and health inequalities. [Google Scholar]

- Fassaert T., De Wit M.A.S., Tuinebreijer W.C., Knipscheer J.W., Verhoeff A.P., Beekman A.T.F. Acculturation and psychological distress among non-Western muslim migrants - a population-based survey. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2009;57(2):132–143. doi: 10.1177/0020764009103647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M., Thayer Z., Wadhwa P.D. Acculturation and health: The moderating role of socio-cultural context. American Anthropologist. 2017;119(3):405–421. doi: 10.1111/aman.12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M., Thayer Z., Wadhwa P.D. Assessment of acculturation in minority health research. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;176:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisillo Vander Veen D. Obesity, obesity health risks, resilience, and acculturation in black African immigrants. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care. 2015;11(3):179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M.M. 1964. Assimilation in American life. New York. [Google Scholar]

- Hall S. 2000. The multicultural question the political economy research centre annual lecture. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt L.M., Schneider S., Comer B. Should ‘‘acculturation’’ be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59:973–986. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin V.L., Nichols J.F., Hofstetter C.R., Ojeda V.D., Song Y.J., Kang S. Osteoporosis and milk intake among Korean women in California: Relationship with acculturation to U.S. Lifestyle. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2013;15(6):1119–1124. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9774-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinskaja-Lahti I., Liebkind K., Horenczyk G., Schmitz P. The interactive nature of acculturation: Perceived discrimination, acculturation attitudes and stress among young ethnic repatriates in Finland, Israel and Germany. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2003;27(1):79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kane J.C., Johnson R.M., Robinson C., Jernigan D.H., Harachi T.W., Bass J.K. Longitudinal effects of acculturation on alcohol use among Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant women in the USA. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire) 2016;51(6):702–709. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agw007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A. Migration und Gesundheit. Prämierte Arbeiten des BKK - innovationspreises Gesundheit 2003, Frankfurt am Main: Mabuse. 2004. Gesundheit und Versorgung von Deutschen Migranten - Ergebnisse eines Surveys in Bielefeld; pp. 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.J., Lee S.J., Ahn Y.H., Bowen P., Lee H. Dietary acculturation and diet quality of hypertensive Korean Americans. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;58(5):436–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser I.A., Gasevic D., Lear S.A. The association between acculturation and dietary patterns of South Asian immigrants. PLoS One. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung M.W., Yen I.H., Minkler M. Community based participatory research: A promising approach for increasing epidemiology's relevance in the 21st century. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;33(3):499–506. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Kwon S.C., Weerasinghe I., Rey M.J., Trinh-Shevrin C. Smoking among Asian Americans: Acculturation and gender in the context of tobacco control policies in New York city. Health Promotion Practice. 2013;14(5):18s–28s. doi: 10.1177/1524839913485757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Class M., Castro F.G., Ramirez A.G. Conceptions of acculturation: A review and statement of critical issues. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(9):1555–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcarne V.L., Chavira D.A., Fernandez S., Liu P.J. The scale of ethnic experience: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2006;86(2):150–161. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8602_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmusi D., Borrell C., Benach J. Migration-related health inequalities: Showing the complex interactions between gender, social class and place of origin. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(9):1610–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G., Gamba R.J. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The bidimensional acculturation scale for Hispanics (BAS) Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18(3):297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Marin G., Sabogal F., Marin B.V., Otero-Sabogal R., Perez-Stable E.J. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company; Pacific Grove, CA: 1996. Culture and psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooren T., Knipscheer J., Kamperman A., Kleber R., Komproe I. The Lowlands Acculturation Scale. Validity of an adaptation measure among migrants in The Netherlands. The Impact of War Studies on the Psychological Consequences of War and Migration. 2001;11(13):49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Morawa E., Erim Y. Acculturation and depressive symptoms among Turkish immigrants in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014;11(9):9503–9521. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110909503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyerman D.R., Forman B.D. Acculturation and adjustment: A meta-analytic study. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1992;14(2):163–200. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla A.M. In: Acculturation, theory, models, and some new findings/ Padilla A.M., editor. Westview Press for the American Association for the Advancement of Science; Boulder, Colo: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas L.A., Pickwell S.M. Acculturation as a risk factor for chronic disease among Cambodian refugees in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40(12):1643–1653. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00344-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J.S. When we talk about American ethnic groups, what do we mean? American Psychologist. 1996;51(9):918–927. [Google Scholar]

- Qin D. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies; 2016. Positionality. [Google Scholar]

- Razum O., Zeeb H., Meesmann U., Schenk L., Bredehorst M., Brzoska P.…Ulrich R. Robert Koch-Institut; Berlin: 2008. Migration und Gesundheit. Schwerpunktbericht der Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield R., Linton R., Herskovits M.J. Memorandum for the study of acculturation. American Anthropologist. 1936;38(1):149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Richman J.A., Gaviria M., Flaherty J.A., Birz S., Wintrob R.M. The process of acculturation: Theoretical perspectives and an empirical investigation in Peru. Social Science & Medicine. 1987;25(7):839–847. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Koch-Institut . 2017. Abschlussbericht der Studie "KABP-Studie mit HIV- und STI-Testangebot bei und mit in Deutschland lebenden Migrant/innen aus Subsahara-Afrika (MiSSA) Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Rodewig K. Stationäre psychosomatische Rehabilitation von Migranten aus der Türkei. Psychotherapeut. 2000;45(6):350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Rudmin Critical history of the acculturation psychology of assimilation, separation, integration, and marginalization. Review of General Psychology. 2003;7(3):250. [Google Scholar]

- Rudmin Constructs, measurements and models of acculturation and acculturative stress. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2009;33(2):106–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rudmin, Wang B., Castro J. Oxford University Press; 2016. Acculturation research critiques and alternative research designs. Handbook of acculturation and health. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut R.G. Reaping what you sow: Immigration, youth, and reactive ethnicity. Applied Developmental Science. 2008;12(2):108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sam D.L. Acculturation: Conceptual background and core components. In: Berry D.L.S.J.W., editor. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY, US: 2006. pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez L. Encyclopedia of geography; 2010. Positionality. 2258-2258. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Hövener C., Schumann M., Schmich P., Gößwald A., Rommel A., Ziese T. Verbesserung der Informationsgrundlagen zur Gesundheit von Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund. Projektbeschreibung und erste Erkenntnisse von IMIRA. Journal of Health Monitoring. 2019;4(1) [Google Scholar]

- Scheppers E., van Dongen E., Dekker J., Geertzen J., Dekker J. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: A review. Family Practice. 2006;23(3):325–348. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schierup C.-U., Alunnd A. Almqvist & Wiksell International; Stockholm: 1987. Will they still be dancing? Integration and ethnic transformation among Yugoslav immigrants in Scandinavia. [Google Scholar]

- Schumann M., Bartig S., Bug M., Koschollek C., Bach M., Lampert T. Acculturation in epidemiological research among migrant populations: A systematic review. 2018. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=88234 Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schwartz S.J., Unger J.B., Zamboanga B.L., Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65(4):237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S.J., Zamboanga B.L., Jarvis L.H. Ethnic identity and acculturation in hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(4):364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon T.A., Parker H. Race and ethnicity in health research. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 1992;14(2):104–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner N. Routledge; New York, NY: 2009. International migration and citizenship today. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson M. Development and validation of the Stephenson Multigroup Acculturation scale (SMAS) Psychological Assessment. 2000;12(1):77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco M., Páez M. Introduction. In: Suárez-Orozco M., Páez M., editors. Latinos: Remaking America. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2002. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Suinn R.M., Ahuna C., Khoo G. The Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity acculturation scale: Concurrent and factorial validation. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1992;52(4):1041–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman N.M., Truong N. “Please extinguish all cigarettes”: The effects of acculturation and gender on smoking attitudes and smoking prevalence of Chinese and Russian immigrants. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2011;35(2):163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson M.D., Hoffman-Goetz L. Defining and measuring acculturation: A systematic review of public health studies with hispanic populations in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(7):983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane N., Mak W. Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, US: 2003. Major approaches to the measurement of acculturation among ethnic minority populations: A content analysis and an alternative empirical strategy acculturation; pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]