Abstract

Fat embolism is common following trauma and is a common autopsy finding in these cases. It may also be seen in non-traumatic cases and is seen in children as well as adults. In comparison fat embolism syndrome (FES) only occurs in a small number of trauma and non-trauma cases. Clinical diagnosis is based on characteristic clinical and laboratory findings. Fat embolism exerts its effect by mechanical blockage of vessels and/or by biochemical means including breakdown of fat to free fatty acids causing an inflammatory response. Fat embolism can be identified at autopsy on microscopy of the lungs using fat stains conducted on frozen tissue, including on formalin fixed but not processed tissue. With FES fat emboli can be seen in other organs including the brain, kidney and myocardium. Fat can also be identified with post-fixation staining, typically with osmium tetroxide. Scoring systems have been developed to try and determine the severity of fat embolism in lung tissue. Fat embolism is also common following resuscitation. When no resuscitation has taken place, the presence of fat on lung histology has been used as proof of vitality. Diagnosis of fat embolism syndrome at autopsy requires analysis of the history, clinical and laboratory findings along with autopsy investigations to determine its relevance, but is an important diagnosis to make which is not always identified clinically. This paper reviews the history, clinical and laboratory findings and diagnosis of fat embolism and fat embolism syndrome at autopsy.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Fat, Embolism, Syndrome, Autopsy, Microscopy

Introduction

Fat embolism is a form of parenchymatous embolism where fat globules enter the venous circulation and then pass to the lungs. The fat globules may pass from the lung circulation into the systemic circulation when the fat globules become lodged in the systemic organs, particularly the brain, kidney, skin, eyes, and myocardium. This may also occur due to a patent foramen ovale. Fat embolism is common following trauma, with reported rates up to 100% (1). It is a common autopsy finding (2 –6), but while only a small proportion of those with fat embolism develop clinically apparent fat embolism syndrome (FES), fat embolism and its effects are probably underappreciated, including at autopsy (7). The identification of fat in vessels is relatively straightforward at autopsy if microscopy is performed and confirmed with appropriate histochemical stains. However, the finding of fat in vessels at autopsy does not mean that the decedent had FES, or even that the fat present has had a significant clinical effect, but requires analysis of the history, clinical, and laboratory findings (if available) along with autopsy investigations to determine its relevance. Fat embolism has been reported in both the adult and pediatric population, including the neonatal period and infancy (8 –12). This paper reviews the clinical features and pathology of fat embolism and FES and its diagnosis at autopsy.

Illustrative Case

A 32-year-old man was involved in a motor vehicle collision. He was fully conscious when admitted to hospital (Glasgow Coma Scale 15/15). He had sustained fractures of his lower limbs including the right femur, right tibia, left malleolus, and left calcaneus. Three days after being admitted he became agitated and became incomprehensible. He required soft restraints and developed tonic-clonic seizures. He was intubated but developed wide complex tachycardia and then pulseless electrical activity which terminated in asystole and he could not be resuscitated. There was a fall in hemoglobin from 143 g/L on admission to 65 g/L 3 days later and platelets from 358 to 188 × 109/L.

He had a history of drug abuse and concerns were expressed that he may have taken illicit drugs in hospital. Toxicology showed therapeutic concentrations of prescribed drugs in both pre and post collapse blood taken clinically and in autopsy samples. There was no evidence of the administration of any illicit drug to account for the agitation and collapse.

Autopsy did not disclose any natural disease to account for death. Microscopic examination revealed fat embolism in the lungs. No fat embolism was seen in sections of the brain.

The acute confusional state with agitation and collapse was attributed to pulmonary fat embolism, and the cause of death was given as complications of multiple injuries. The manner of death was accident.

Discussion

History of Fat Embolism

Sevitt, in his book on fat embolism, reviewed the history of fat embolism (13). It was first recognized in humans in the 19th century. Fat embolism had been observed in dogs in the 17th century when they had been injected with milk in an experiment. Zenker observed fat embolism in 1861 in a man who had been crushed, but Zenker attributed the fat from gastric contents. In 1862, Wagner described fat emboli in the lung in a patient with pyemia and there was confusion between fat embolism and embolic abscesses for several years. Interest in this area significantly increased at this time and Virchow conducted experiments relating to fat embolism on dogs in 1862 and 1865. In the same year, Wagner reported on 48 cases, which included many cases with fractures. In 1873, the first description of fat embolism in a living person was recorded by von Bergmann. Cerebral fat embolism was also described in the 19th century (13). In the late 19th century, the view that fat embolism was inevitably fatal or part of the cause of death was challenged. It was recognized that fat embolism was common after fractures. In 1924, Gauss classified fat embolism clinically into three forms: 1) a respiratory form from pulmonary emboli manifest by respiratory symptoms and signs; 2) cardiac form from embolism to small coronary vessels with tachycardia, dyspnea, and hypotension; and 3) cerebral form due to cerebral embolism (13). Publications continued throughout the 20th century and the clinical features and autopsy findings in FES were clarified. Fat embolism was recognized in nontraumatic causes, but FES is still not fully elucidated.

Causes of Fat Embolism

Fat embolism is most commonly seen following blunt trauma, particularly from long bone and pelvic fractures (14, 15). It may be seen in trauma to soft tissues without fracture of bones and following hip surgery (16). It may also follow burns, liposuction, cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, diabetes mellitus, decompression sickness, corticosteroid therapy, and parenteral lipid infusion. Fat embolism is seen in sickle cell disease and hemorrhagic pancreatitis (17 –21). It has also been reported in carbon tetrachloride poisoning (22). In sickle cell disorders, fat embolism arises from bone marrow necrosis. With pancreatitis, there is fat necrosis. Fat embolism has been reported with massive hepatic necrosis with fatty liver, and carbon tetrachloride poisoning also causes fatty liver (23). It has also been reported in heat exposure but in none of the cases was it felt that the fat embolism caused death (24). The causes of fat embolism are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1:

Causes of Fat Embolism

| Fractures of bones – particularly long bones and pelvis |

| Soft tissue trauma |

| Osteomyeltis |

| Burns |

| Liposuction |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass surgery |

| Hip surgery |

| Decompression sickness, |

| Corticosteroid therapy |

| Parenteral lipid infusion. |

| Sickle cell disease |

| Hemorrhagic pancreatitis |

| Carbon tetrachloride poisoning |

| Alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| Massive hepatic necrosis with fatty liver |

| Heat exposure |

The Pathophysiology of Fat Embolism Syndrome

The main evidence for origin of fat embolism in long bone and pelvic fracture appears to be from traumatized bone fat and bone marrow that travels to the lungs and blocks the pulmonary circulation (1). This is known as the mechanical theory. The presence of bone marrow emboli in lung sections supports this, along with experiments showing labeled fat going to the lung and the observation that the application of a tourniquet to a fractured limb stops fat embolism. Bone marrow emboli however are not always present. The mechanical theory involves blockage of vessels and local damage as a consequence, manifest in the lungs, brain, and kidney. The second theory, which is not mutually exclusive to the mechanical theory, is the biochemical theory. This theory proposes biochemical changes including fat globules entering the pulmonary vasculature where they are broken down to free fatty acids leading to a microvascular inflammatory response with the development of acute lung injury (25). However, one problem with this theory is that the bone marrow is mostly composed of neutral fat and do not display this effect, though in vivo it is likely that neutral fats are broken down to free fatty acids. Another part of the biochemical theory is that trauma elevates plasma lipase which precede any rise in free fatty acids. (25). Raised levels of interleukin-6 have been demonstrated in patients with FES at 12 hours in comparison with trauma patients without FES (26). The biochemical theories partly account for the delayed onset of symptoms. Hypovolemic shock may also contribute to vascular permeability leading to platelet activation with the presence of bone marrow acting as a place where platelets may adhere (25). Systemic fat embolism is believed to occur when either fat passes through a patent foramen ovale or by fat passing through capillaries in the lung to enter the systemic circulation.

Clinical Features and Incidence of Fat Embolism Syndrome

Hypoxemia following long bone fractures is well recognized (27 –29). This may be due to pulmonary fat embolism without the development of full blown FES. Hypoxemia occurs in around one-third of patients with long bone fractures, but FES was reported in 19% of patients with major trauma in a series from Belfast and in 22% in a study from Helsinki (30, 31). When internal fixation of fractures was instituted, the incidence fell below 2% (32). In a retrospective study of over 3000 long bone fractures, Bulger and colleagues found an incidence of 0.9%, and in a prospective study, Fabian and colleagues found an incidence of at least 11% based upon increased pulmonary shunt fraction (29, 33). Pinney and colleagues found an overall incidence of 4% following isolated femoral shaft fractures (34). No fat embolism was seen when intramedullary nailing occurred less than 10 hours after injury, while 10% of those with delayed nailing developed FES.

Fat embolism syndrome has a number of features and have been divided into major and minor features (35). Major features include disturbances of consciousness, respiratory symptoms with hypoxia and tachypnea, and petechiae in the skin. Minor features include pyrexia, retinal petechiae and/or retinal fat, urinary fat globules, sudden decrease in hemoglobin and platelets, fat in the sputum, and a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate ( Table 2 ). Respiratory features are stated to be present in 75% of patients (19). A petechial rash has been reported in 50-60% of cases (Image 1) (14). Neurological manifestations of FES may be present in the absence of other major manifestations of FES. Neurological symptoms may be localized or diffused. Impaired consciousness was present in all 12 patients reviewed by Jacobson and colleagues (36). In 8 patients, only encephalopathic features were present, typical of an acute confusional state not explained by hypoxemia. In 4 patients, there were also focal features. These included stupor, pupillary dilation, hemiplegia, and a conduction aphasia.

Table 2:

Clinical Features of Fat Embolism Syndrome (Gurd)

| Major |

| Petechiae |

| Hypoxemia |

| Cerebral symptoms |

| Minor |

| Tachycardia (>110/min) |

| Pyrexia (>38.5℃) |

| Retinal emboli |

| Renal changes (oliguria/anuria) |

| Laboratory findings |

| Fat macroglobulemia/lipuria |

| Sudden decrease in hemoglobin level |

| Sudden thrombocytopenia |

| Increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| Fat in sputum |

Image 1:

Petechial rash on the torso in fat embolism syndrome.

Onset of symptoms of FES is typically anywhere between 12 and 72 hours with an average time between injury and FES of 48.5 hours. Rarely, presentation may be earlier (37).

A clinical scoring system has been developed to aid in the diagnosis of FES (38). The scoring system is summarized in Table 3 .

Table 3:

Clinical Scoring System For Fat Embolism Syndrome (Schonfeld)

| Petechial rash (5 points) |

| Diffuse infiltration on chest x-ray (4 points) |

| Hypoxemia (3 points) |

| Fever (1 point) |

| Tachycardia (1 point) |

| Tachypnea (1 point) |

| Confusion (1 point) |

Score of 5 points or more established diagnosis of FES

Postmortem Diagnosis of Fat Embolism

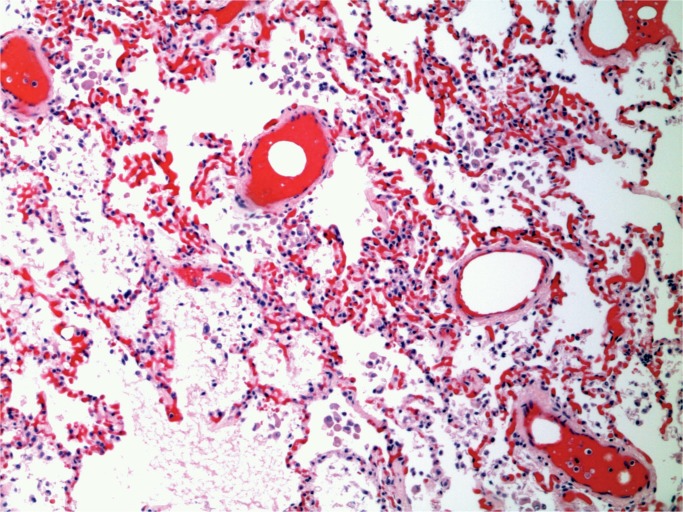

The postmortem diagnosis is relatively straightforward when fat stains are appropriately combined with routine histological sections. In the absence of fat stains, fat in vessels can be deduced from hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of the lungs. Fat is removed in the process of developing paraffin sections, but the dissolved fat globules leave vessels distended in the stained sections (Image 2). However, the use of fat stains increases the diagnostic incidence. Scully reported that the incidence increased from 79% to 93% using oil red O stains (5).

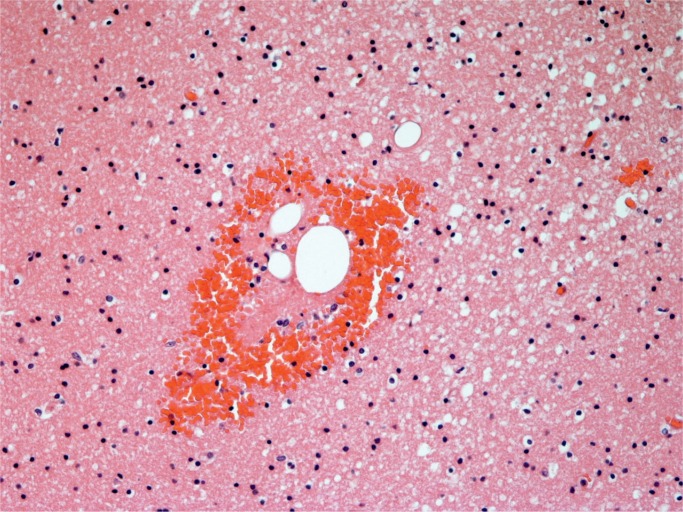

Image 2:

Lung with fat emboli in distended vessels (H&E, x100).

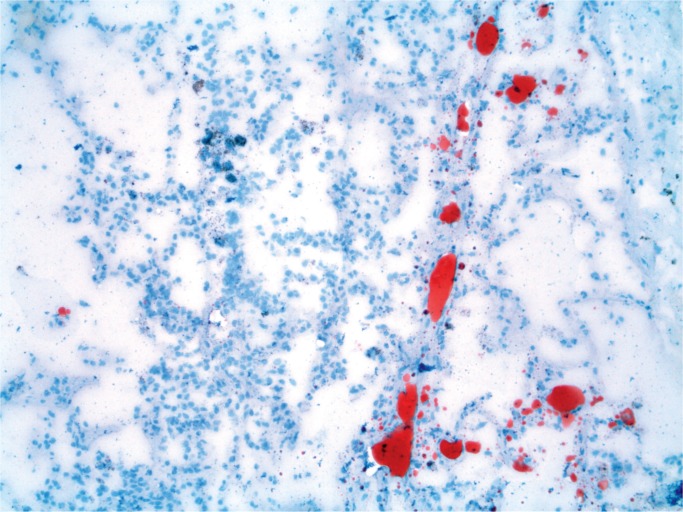

Fat itself can be demonstrated in vessels on fresh or formalin-fixed tissue on frozen sections using fat stains such as oil red O or Sudan Black (39). The fat globules are red or black, depending on the stain and are visible in vessels (Image 3). If no frozen sections have been performed on fresh tissue, this does not preclude using formalin fixed but unprocessed tissue. Thus, the tissues stored in a stock pot can be used with frozen sections on the formalin-fixed tissue.

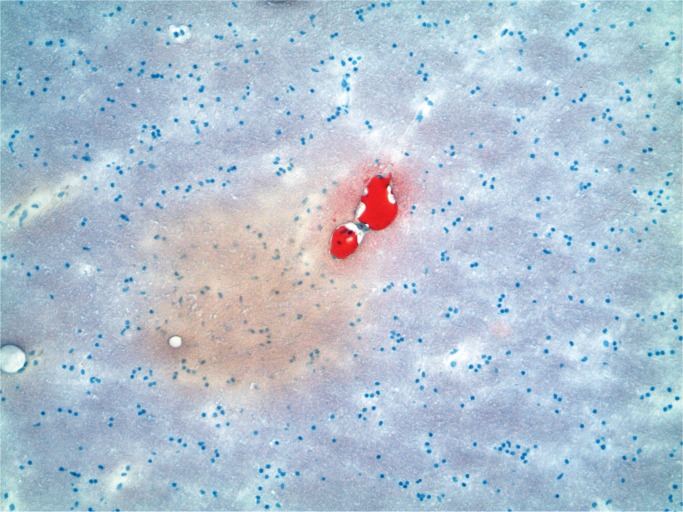

Image 3:

Lung with fat emboli (Oil red O, x100).

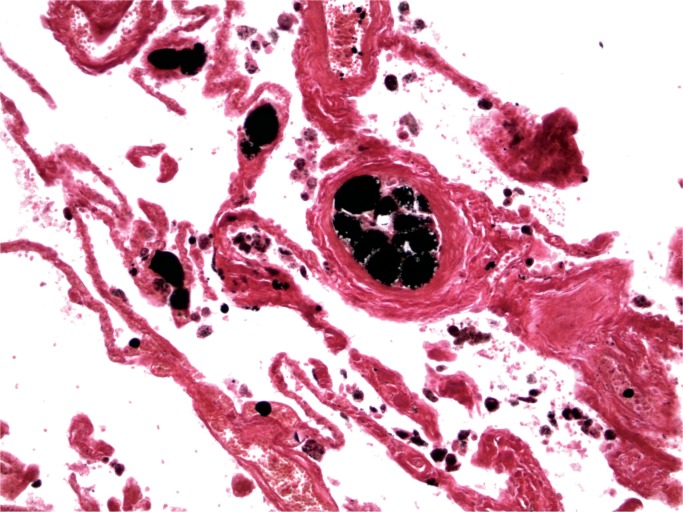

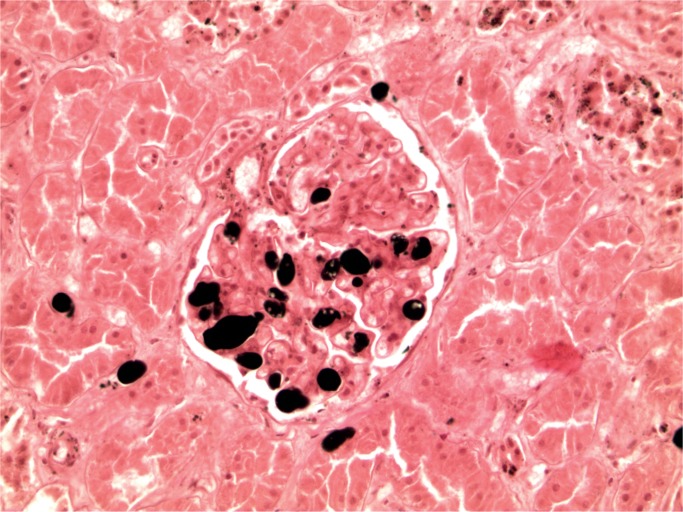

A further technique that can be employed is the use of osmium tetroxide after formalin fixation (post-fixation) (40, 41). Tissue is then paraffin-embedded, which allows the production of normal sections with fat globules staining black (Image 4). The advantages of using this technique are that greater amounts of fat staining are visible and other detail can be seen in the same section. The disadvantages include the cost— osmium tetroxide is expensive, it penetrates poorly, and it is also toxic, so care must be taken with its use. This has led to a search for other agents to identify fat postfixation. Tracy and Walia have reported a method using linoleic acid in 70% ethylene glycol and then treatment with chromic acid followed by sodium bicarbonate. The paraffin sections are then stained with a lipid soluble dye such as oil red O stains (42).

Image 4:

Lung with fat emboli (Osmium tetroxide, x100).

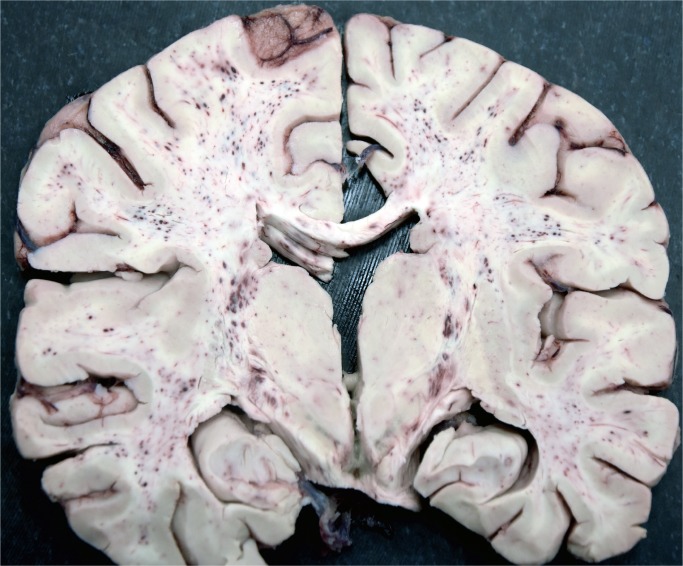

Cerebral fat embolism is an important complication. Macroscopically, there are prominent petechial hemorrhages. These are seen diffusely in the white matter (Image 5) with sparing of the gray matter. In the cerebellum, they may be seen in the cortex and white matter and they are present brain stem but decrease in the spinal cord caudally (43). On microscopy, fat is seen as distending vessels with perivascular hemorrhage present and fat can be demonstrated with fat stains (Images 6 and 7). Fat may also be seen in the kidneys, when it is present in glomerular vessels (Images 8 and 9). Petechial hemorrhages in skin are caused by fat in vessels, which can be seen in the dermis. Rarely, fat emboli may be seen in the myocardium.

Image 5:

Brain showing fat embolism with prominent petechiae in white matter

Image 6:

Cerebral fat embolism (H&E, x100).

Image 7:

Fat embolism in the brain (Oil red O, x100).

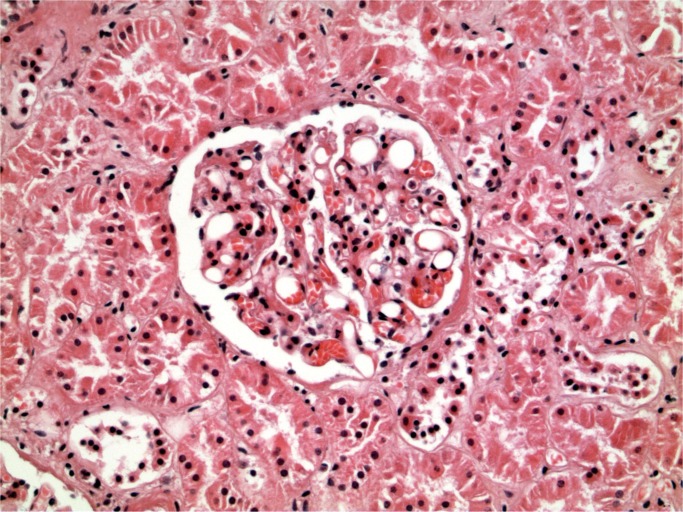

Image 8:

Renal fat embolism (H&E, x200).

Image 9:

Renal fat embolism (Osmium tetroxide, x200).

The tissue reaction to fat emboli has been reported to be seen within the first 24 hours (44). This consists of an initial neutrophil reaction and increases up to 72 hours with eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells present. Emboli can show scalloping and gradually decrease in size and dissolve in 7 to 10 days.

An interesting technique for the examination of fat embolism at autopsy has been developed by Sigrist and utilized by Voisard and colleagues in a study of the incidence fat embolism from Iceland (45). The technique utilizes a twin-edged knife. Holding a lung lobe, the knife is pulled through a cut in the lung and a sample of tissue is obtained between the blades, which is then placed in water to hemolyze the red blood cells. When the tissue appears transparent, it is placed on a slide and stained with an oil stain, Sudan III in the case of Voisard and colleagues, and viewed under the microscope. The samples produced were 0.25 to 0.5 mm thick. In comparison, frozen sections are typically around 10 μ thick when using fat stains. Sigrist showed that using Falzi grading (see below) there was only a difference of one grade at most between different tissue sections from the same case, while with cryostat sections, he found it to be 2 grades. The sections need to be viewed in a few hours. The tissue sections with the twin knife technique produce treelike units of the small lung arteries and their branches as a whole.

Fat embolism has been identified with putrefaction present. Nikolić and colleagues identified pulmonary fat embolism in an 80-year-old female with a hip fracture using Sudan III–stained frozen sections (46). In the study of Voisard and colleagues, small amounts of fat were found in nontraumatic cases with putrefaction (45).

Postmortem Scoring Systems for Presence of Fat Embolism

Attempts have been made to grade the degree of fat embolism based upon examination of lung sections at autopsy. Scully examined 110 battlefield casualties from the Korean War for fat embolism at autopsy (5). Lung fat embolism was graded from 0 to 8, grade 1 representing less than ten small emboli per section and grade 8 signifying the presence of emboli in a majority of high-powered fields. Renal fat content was also graded from 0 to 8.

Mason (see Table 4 ) classified fat embolism as grade 0 when no emboli were seen, grade 1 if emboli were not immediately apparent in two or three microscopic fields using a ×2.5 objective, grade 2 if easily found, grade 3 when emboli were present in large numbers, and grade 4 when they were present in potentially fatal concentration (47). Grade 4 was not otherwise described. Mason stated that the evidence was that fat embolism was evenly distributed in the lung, so any block of lung will do for examination. Examination of controls showed grade 0 was the most common concentration and grade 1 was recorded in a small number of cases. Grades 2 and 3 were rare, but included a case of fat embolism in a patient with leukemia who underwent multiple bone marrow punctures and a case of fat embolism post radical mastectomy.

Table 4:

Mason Scoring System

| Grade | Emboli Present |

|---|---|

| 0 | No emboli |

| 1 | Emboli were not immediately apparent in two or three microscopic fields |

| 2 | Emboli easily found |

| 3 | Emboli present in large numbers |

| 4 | Emboli present in potentially fatal concentration |

Falzi and colleagues developed a scoring system, which was adapted by Janssen (48). The grading is summarized in Table 5 . Fat embolism was scored as grade 0—not fat embolism (punctiform when present—sporadic and not in every microscopic field), grade 1—light fat embolism when the form of embolism was described as drop shaped and sporadic in every microscopic field, grade 2—when multiple, disseminated in every microscopic field and sausage shaped or rounded, and grade 3—when antler shaped and numerous everywhere, in every microscopic field.

Table 5:

Falzi Scoring System (Adapted by Janssen)

| Grade | Emboli Present |

|---|---|

| 0 | Not fat embolism (punctiform when present) - sporadic |

| 1 | Light fat embolism drop-shaped, sporadic in every microscopic field |

| 2 | Multiple, disseminated, sausage shaped or rounded |

| 3 | Every microscopic field, antler shaped and numerous everywhere |

Mudd and colleagues graded fat embolism from 0 to 4, where 0 was no emboli (×4), grade 1 when there were one to ten emboli in the entire section (×4), grade 2 was when there were one to five emboli in the majority of low-power fields (×10), grade 3 when there were one to five emboli in the majority of high-power fields (×40), and grade 4 was recorded when there were four, five, or more emboli in the majority of high-power fields (×40) (49).

Incidence of Fat Embolism at Autopsy

Fat embolism is common at autopsy in trauma cases. Vance reported an incidence in his series of trauma cases of 75%, Robb-Smith 81%, Wyatt and Khoo 100%, and Scully 91% (3 –5, 50). Scully reported that in only 19%, the grade was more than slight. Systemic embolism was classified as more than slight in only 4% of Scully’s series. Emson examined 100 patients dying from trauma (6) and recorded fat embolism present in 89% of injured patients (6).

The diagnosis of FES at autopsy can be relatively easy if there is access to clinical and laboratory data. This can then be combined with autopsy findings to make the diagnosis. Miller and Prahlow have proposed criteria for making the diagnosis at autopsy (51). The difficult group are those cases where there is sudden collapse with few clinical findings to suggest clinically significant fat embolism. They suggested that in cases of sudden death occurring in trauma patients where there is only a mild amount of fat emboli identified within the lungs, but with no other explanation for death, pathologists should also consider the possibility of FES. In such cases, the term possible or probable may be used in combination with FES.

The problem is of course how much fat is enough fat. The scoring systems described above may help, but ultimately it will be a judgment call as to whether there are enough pathological changes to provide the cause of death.

Fat Embolism and Resuscitation

Fat embolism is very common following resuscitation, which complicates the interpretation of histology in cases of trauma and resuscitation. Eriksson and colleagues found pulmonary fat embolism in 7 of 10 patients who had cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) but no trauma (7). Samdanci and colleagues found isolated pulmonary fat embolism in 402 of 4118 autopsied cases (52). They graded fat embolism from 1 to 3 based upon Scully and Glass and modified by Mudd and colleagues (49). In 100 cases, there was CPR performed in cases without trauma, principally in cases with myocardial infraction. In these 100 cases, every case had a degree of pulmonary fat embolism. Higher scores for fat embolism were present in trauma cases compared with nontrauma cases.

Fat Embolism as Proof of Vitality

In sudden traumatic deaths, a question may arise as to whether the victim was dead before the trauma was inflicted. The presence of fat embolism has been used to determine whether the heart was beating when the injuries were inflicted. The concept is reviewed extensively in Mason’s textbook on aviation accident pathology published in 1962 (47). Mason concluded that the presence of fat embolism was deemed highly associated with trauma and a beating heart. Resuscitation, as detailed above, negates the validity this determination.

Postmortem Imaging and Fat Embolism

There have been recent publications discussing the postmortem computed tomography (PMCT) and magnetic resonance imaging findings in fat embolism compared with microscopy. Makino and colleagues stated that massive pulmonary fat embolism can be suggested by a “fat-fluid level” in the right ventricle or pulmonary trunk or fat in the pulmonary artery branches (53). Chatzaraki and colleagues examined 366 cases of pulmonary fat embolism cases and compared them with controls. Degree of fat embolism was scored according to Falzi grading described above (54). Eighteen cases had a fat layer seen on PMCT. In two cases, there was no antemortem trauma, but CPR had been conducted. In 2 further cases, a fat layer was present when none was seen on histology. Both cases involved massive trauma with instantaneous death. Overall, only a small minority of cases had evidence of fat embolism identified on PMCT and histology remains the most important diagnostic tool at autopsy.

Homicide by Soft Tissue Injury

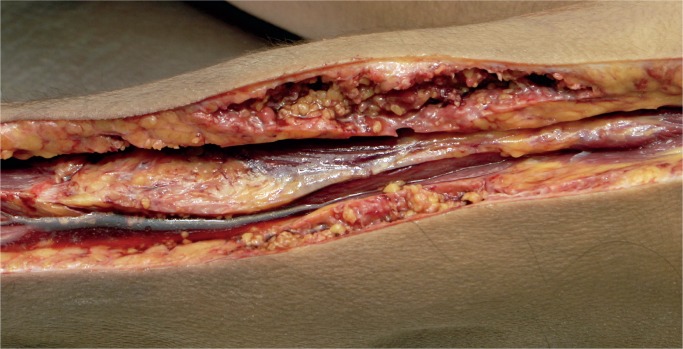

Cases of soft tissue damage from beatings have been reported for over a century. In 1920, Beurger, quoted by Vance, reported the case of a 72-year-old woman who was beaten with a club and suffered extensive damage with separation of the dermis from the muscular fascia (3). The subcutaneous fat was torn forming pockets full of blood and oil. No fractures were noted, and large numbers of fat emboli were seen in the lungs at autopsy. We have encountered a similar case. Macroscopically, there was no significant external bruising on the limbs but on subcutaneous dissection the fat was torn and separated (Images 10 and 11). On microscopy, these areas showed acute hemorrhage and chronic inflammation with hemosiderin present (Images 12 and 13). There was both fat embolism in the lungs and myoglobinuria in the kidneys. Lee and Opeskin reported several homicide cases where death occurred in the presence of superficial injury only (55). Fat embolism was seen in one case. Cluroe reported another case in which fat embolism was seen following a beating with soft tissue injury (56). The cause of death was attributed to blood loss in the soft tissues. Nichols et al reported fat embolism in a two-year-old child who had been beaten (57). There were multiple blunt traumatic injuries but no skeletal fractures. Pulmonary, cerebral, and renal fat emboli were identified at autopsy.

Image 10:

Fat necrosis in the arm.

Image 11:

Fat necrosis in the leg.

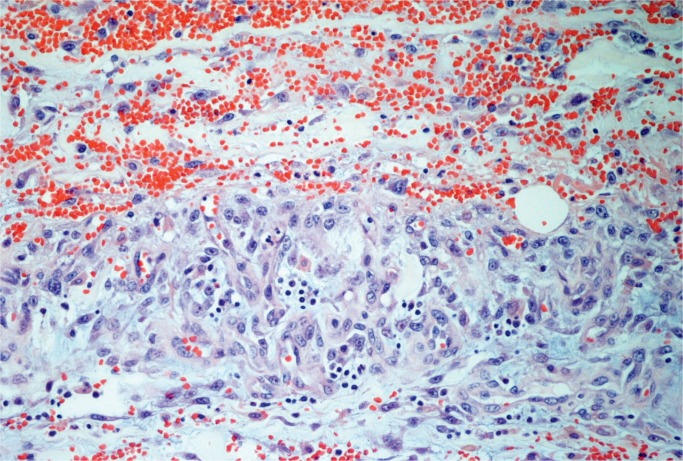

Image 12:

Acute hemorrhage with chronic inflammation (H&E, x200).

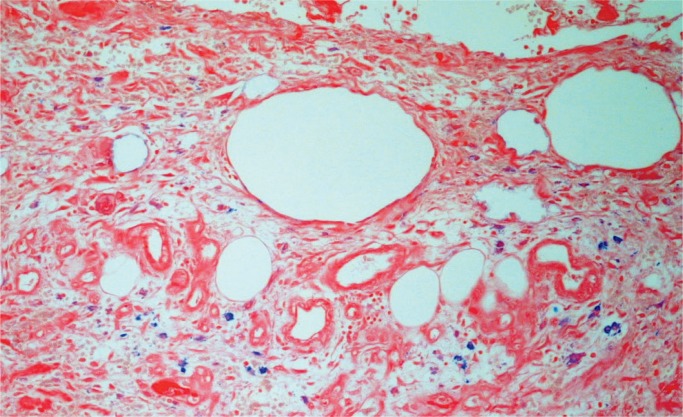

Image 13:

Hemosiderin macrophages in damaged fat tissue (Perls’ stain, x200).

Silicone Injection

Silicone is used as a cosmetic agent to enhance certain anatomical areas. It has been associated with death when the silicone enters the circulation (58). This is often when unlicensed practitioners inject silicone for such procedures as breast or buttock enhancement. Symptoms have been reported to begin within minutes to up to 72 hours after injection and include hypoxia, dyspnea, fever, petechiae, and neurological symptoms. They thus have an overlap with fat embolism including microscopic features. Histologically, the globules may be seen in vessels. Acute lung injury and intra-alveolar hemorrhage have been reported on biopsy (59). Systemic silicone emboli may be seen in the heart, liver, spleen, kidneys, and brain (60). Chung and colleagues identified the silicone globules in tissues using infrared spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy on lungs (61).

Conclusion

Fat embolism is common at autopsy in trauma cases. It may also occur in nontraumatic conditions. Identification is by histological examination of the lungs. It can be seen on routine hematoxylin and eosin stains and confirmed with simple special stains. It can be identified using formalin-fixed tissue with fat stains on frozen sections. Fat embolism is very common following resuscitation. Clinicopathological correlation is required to diagnose FES, but typically these patients will be in hospital following trauma.

Authors

Christopher M. Milroy MBChB MD LLB BA LLM FRCPath FFFLM FRCPC DMJ, The Ottawa Hospital - Anatomical Pathology

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work.

Jacqueline L. Parai MD MSc FRCPC, The Ottawa Hospital - Anatomical Pathology

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

Statement of Informed Consent: No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscript

Disclosures & Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1). Hulman G. The pathogenesis of fat embolism. J Pathol. 1995. May; 176(1):3–9. PMID: 7616354 10.1002/path.1711760103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Lehman EP, McNattin RF. Fat embolism: II. Incidence at postmortem. Arch Surg. 1928. August; 17(2):179–89. 10.1001/archsurg.1928.01140080003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Vance BM. The significance of fat embolism. Arch Surg. 1931. September; 23(3):426–65. 10.1001/archsurg.1931.01160090071002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Robb-Smith AH. Pulmonary fat-embolism. Lancet. 1941. February; 237(6127):135–41. 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)77494-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Scully RE. Fat embolism in Korean battle casualties: its incidence, clinical significance, and pathologic aspects. Am J Pathol. 1956. May-Jun; 32(3):379–403. PMID: 13313711. PMCID: PMC1942694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Emson HE. Fat embolism studied in 100 patients dying after injury. J Clin Pathol. 1958. January; 11(1):28–35. PMID: 13502457. PMCID: PMC1024125 10.1136/jcp.11.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Eriksson EA, Pellegrini DC, Vanderkolk WE, et al. Incidence of pulmonary fat embolism at autopsy: an undiagnosed epidemic. J Trauma. 2011. August; 71(2):312–5. PMID: 21825932 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182208280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Weisz GM, Rang M, Salter RB. Posttraumatic fat embolism in children: review of the literature and of experience in the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. J Trauma. 1973. June; 13(6):529–34. PMID: 4711285 10.1097/00005373-197306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Barson AJ, Chistwick ML, Doig CM. Fat embolism in infancy after intravenous fat infusions. Arch Dis Child. 1978. March; 53(3):218–23. PMID: 417679. PMCID: PMC1545144 10.1136/adc.53.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Levene M, Wigglesworth JS, Desai R. Pulmonary fat accumulation after intralipid infusion in the preterm infant. Lancet. 1980. October 18; 2(8199):815–8. PMID: 6107497 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Mughal MZ, Robinson MJ, Duckworth W. Neonatal fat embolism and agglutination of intralipid. Arch Dis Child. 1984. November; 59(11): 1098–9. PMID: 6439127. PMCID: PMC1628807 10.1136/adc.59.11.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Eriksson EA, Rickey J, Leon SM, et al. Fat embolism in pediatric patients: an autopsy evaluation of incidence and etiology. J Crit Care. 2015. February; 30(1):221.e1-5. PMID: 25306239 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Sevitt S. Fat Embolism. London (UK): Butterworths; 1962. Chapter 1, The background and perspective of fat embolism; p 1-18. [Google Scholar]

- 14). Gossling HR, Pellegrini VD., Jr. Fat embolism syndrome: a review of the pathophysiology and physiological basis of treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982. May; (165):68–82. PMID: 7042168 10.1097/00003086-198205000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Talbot M, Schemitsch EH. Fat embolism syndrome: history, definition, epidemiology. Injury. 2006. October; 37 Suppl 4:S3-7 PMID: 16990059 10.1016/j.injury.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Dalavayi S, Prahlow JA. Sudden death during hip replacement surgery: a case series. J Forensic Leg Med. 2019 Aug; 66:138-43. PMID: 31302444 10.1016/j.jflm.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17). Lynch MJ. Nephrosis and fat embolism in acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1954. November; 94(5):709–17. PMID: 13206453 10.1001/archinte.1954.00250050023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Scroggins C, Barson PK. Fat embolism syndrome in a case of abdominal lipectomy with liposuction. Md Med J. 1999. May-Jun; 48(3):116–8. PMID: 10394227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Taviloglu K, Yanar H. Fat embolism syndrome. Surg Today. 2007; 37(1):5–8. PMID: 17186337 10.1007/s00595-006-3307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Blacker E, Tsitsikas D. Fat embolism syndrome in sickle cell disease: a case series. Br J Haematol. 2018;181 (Suppl 1):124.28106255 [Google Scholar]

- 21). Jones JP, Jr, Engleman EP, Najarian JS. Systemic fat embolism after renal homotransplantation and treatment with corticosteroids. N Engl J Med. 1965. December 30; 273(27):1453–8. PMID: 5322324 10.1056/NEJM196512302732703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). MacMahon HE, Weiss S. Carbon tetrachloride poisoning with macroscopic fat in the pulmonary artery. Am J Pathol. 1929. November; 5(6):623–630.3. PMID: 19969878. PMCID: PMC2007268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Schulz F, Trübner K, Hilderbrand E. Fatal fat embolism in acute hepatic necrosis with associated fatty liver. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1996. September; 17(3):264–8. PMID: 8870880 10.1097/00000433-199609000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Inoue H, Ikeda N, Tsuji A, et al. Pulmonary fat embolization as a diagnostic finding for heat exposure. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2009. January; 11(1):1–3. PMID: 18657464 10.1016/j.legalmed.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Mellor A, Soni N. Fat embolism. Anaesthesia. 2001. February; 56(2):145–54. PMID: 11167474 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.01724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Prakash S, Sen RK, Tripathy SK, et al. Role of interleukin-6 as an early marker of fat embolism syndrome: a clinical study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013. July; 471(7):2340–6. PMID: 23423626. PMCID: PMC3676609 10.1007/s11999-013-2869-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Ross AP. The fat embolism syndrome: with special reference to the importance of hypoxia in the syndrome. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1970. March; 46(3):159–71. PMID: 4910880. PMCID: PMC2387738. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Wong MW, Tsui HF, Yung SH, et al. Continuous pulse oximeter monitoring for inapparent hypoxemia after long bone fractures. J Trauma. 2004. February; 56(2):356–62. PMID: 14960980 10.1097/01.TA.0000064450.02273.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Fabian TC, Hoots AV, Stanford DS, et al. Fat embolism syndrome: prospective evaluation in 92 fracture patients. Crit Care Med. 1990. January; 18(1):37–46. PMID: 2293968 10.1097/00003246-199001000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Gurd AR. Fat embolism: an aid to diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970. November; 52(4):732–7. PMID: 5487573 10.1302/0301-620x.52b4.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Riska EB, Myllynen P. Fat embolism in patients with multiple injuries. Orthop Trauma Direct. 2009. November; 7(06):29–33. 10.1055/s-0028-1100871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Riska EB, von Bonsdorff H, Hakkinen S, et al. Prevention of fat embolism by early internal fixation of fractures in patients with multiple injuries. Injury. 1976. November; 8(2):110–6. PMID: 1002284 10.1016/0020-1383(76)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Bulger EM, Smith DG, Maier RV, Jurkovich GJ. Fat embolism syndrome: a 10-year review. Arch Surg. 1997. April; 132(4):435–9. PMID: 9108767 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430280109019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Pinney SJ, Keating JF, Meek RN. Fat embolism syndrome in isolated femoral fractures: does timing of nailing influence incidence? Injury. 1998. March; 29(2):131–3. PMID: 10721407 10.1016/s0020-1383(97)00154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Gurd AR, Wilson RI. The fat embolism syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1974. August; 56B(3):408–16. PMID: 4547466 10.1302/0301-620x.56b3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Jacobson DM, Terrence CF, Reinmuth OM. The neurologic manifestations of fat embolism. Neurology. 1986. June; 36(6):847–51. PMID: 3703294 10.1212/wnl.36.6.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Cronin KJ, Hayes CB, Moghadamian ES. Early-onset fat embolism syndrome: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2018. Apr-Jun; 8(2):e44. PMID: 29952778 10.2106/JBJS.CC.17.00175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Schonfeld SA, Ploysongsang Y, DiLisio R, et al. Fat embolism prophylaxis with corticosteroids: a prospective study in high-risk patients. Ann Intern Med. 1983. October; 99(4):438–43. PMID: 6354030 10.7326/0003-4819-99-4-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Bancroft JD, Stonard JH. Fat stains and the Sudan dyes In: Survana SK, Layton C, Bancroft C, editors. Bancroft’s theory and practice of histological techniques. 8th ed Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2019. p 496. [Google Scholar]

- 40). Abramowsky CR, Pickett JP, Goodfellow BC, Bradford WD. Comparative demonstration of pulmonary fat emboli by “en bloc” osmium tetroxide and oil red O methods. Hum Pathol. 1981. August; 12(8):753–5. PMID: 7026413 10.1016/s0046-8177(81)80179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41). Davison PR, Cohle SD. Histologic detection of fat emboli. J Forensic Sci. 1987. September; 32(5):1426–30. PMID: 2444667 10.1520/jfs11190j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42). Tracy RE, Walia P. A method to fix lipids for staining fat embolism in paraffin sections. Histopathology. 2002. July; 41(1):75–9. PMID: 12121240 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43). Kamenar EL, Burger PC. Cerebral fat embolism: a neuropathological study of a microembolic state. Stroke. 1980. Sep-Oct; 11(5):477–84. PMID: 7423578 10.1161/01.str.11.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44). Reidbord HE. Microscopic diagnosis in forensic pathology. Springfield (IL): Charles C Thomas; 1980. Chapter 8, Microscopic features of emboli; p 226–30. [Google Scholar]

- 45). Voisard MX, Schweitzer W, Jackowski C. Pulmonary fat embolism—a prospective study within the forensic autopsy collective of the Republic of Iceland. J Forensic Sci. 2013. January; 58 Suppl 1:S105-11. PMID: 23106443 10.1111/1556-4029.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46). Nikolić S, Živković V, Strajina V, et al. Lung fat embolism in a body changed by putrefaction: a hip fracture antemortem in origin. Med Sci Law. 2012. July; 52(3):178–80. PMID: 22833487 10.1258/msl.2011.011024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47). Mason JK. Aviation accident pathology: a study of fatalities. London, United Kingdom: Butterworth; 1962. 358 p. [Google Scholar]

- 48). Janssen W. Forensic histopathology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1984. 402 p. [Google Scholar]

- 49). Mudd KL, Hunt A, Matherly RC, et al. Analysis of pulmonary fat embolism in blunt force fatalities. J Trauma. 2000. April; 48(4):711–5. PMID: 10780606 10.1097/00005373-200004000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50). Wyatt JP, Khoo P. Fat embolism in trauma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1950. July; 20(7):637–40. PMID: 15432360 10.1093/ajcp/20.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51). Miller P, Prahlow JA. Autopsy diagnosis of fat embolism syndrome. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2011. September; 32(3):291–9. PMID: 21817869 10.1097/PAF.0b013e31822a6428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52). Turkmen Samdanci E, Reha Celik M, Pehlivan S, et al. Histopathological evaluation of autopsy cases with isolated pulmonary fat embolism (IPFE): is cardiopulmonary resuscitation a main cause of death in IPFE? Open Access Emerg Med. 2019. June 7; 11:121–7. PMID: 31239793. PMCID: PMC6559766 10.2147/OAEM.S194340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53). Makino Y, Kojima M, Yoshida M, et al. Postmortem CT and MRI findings of massive fat embolism. Int J Legal Med. 2019. August 2 PMID: 31375910 10.1007/s00414-019-02128-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54). Chatzaraki V, Heimer J, Thali MJ, et al. Approaching pulmonary fat embolism on postmortem computed tomography. Int J Legal Med. 2019. November; 133(6):1879–87. PMID: 30972495 10.1007/s00414-019-02055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55). Lee KA, Opeskin K. Death due to superficial soft tissue injuries. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1992. September; 13(3):179–85. PMID: 1476118 10.1097/00000433-199209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56). Cluroe AD. Superficial soft-tissue injury. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1995. June; 16(2):142–6. PMID: 7572870 10.1097/00000433-199506000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57). Nichols GR, 2nd, Corey TS, Davis GJ. Nonfracture-associated fatal fat embolism in a case of child abuse. J Forensic Sci. 1990. March; 35(2):493–9. PMID: 2329342 10.1520/jfs12853j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58). Restrepo CS, Artunduaga M, Carrillo JA, et al. Silicone pulmonary embolism: report of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009. Mar-Apr; 33(2):233–7. PMID: 19346851 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31817ecb4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59). Schmid A, Tzur A, Leshko L, Krieger BP. Silicone embolism syndrome: a case report, review of the literature, and comparison with fat embolism syndrome. Chest. 2005. June; 127(6):2276–81. PMID: 15947350 10.1378/chest.127.6.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60). Price EA, Schueler H, Perper JA. Massive systemic silicone embolism: a case report and review of literature. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2006. June; 27(2):97–102. PMID: 16738424 10.1097/01.paf.0000188072.04746.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61). Chung KY, Kim SH, Kwon IH, et al. Clinicopathologic review of pulmonary silicone embolism with special emphasis on the resultant histologic diversity in the lung: a review of five cases. Yonsei Med J. 2002. April; 43(2):152–9. PMID: 11971208 10.3349/ymj.2002.43.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]