Abstract

Deaths related to hostage situations occur in many forms, as these situations can easily escalate as a result of many confounding variables. When approaching such cases, forensic pathologists and death investigators should be mindful of the many details that should be well-documented at the scene and during autopsy to ensure that the correct conclusions and death certification are determined. This case report highlights a death in a hostage situation and the importance of correlating scene information and autopsy findings. An elderly female hostage was ambulating with a walker away from her ex-husband’s home, after police negotiations successfully convinced her ex-husband to release her. The ex-husband then appeared at the door, brandishing a weapon, at which time a police officer shot at the man. Instead of striking the man, the rifle’s projectile struck the woman in the chest. Subsequent investigation revealed that, although the police officer had a “clear shot” via the rifle sights, the muzzle end of the rifle was obstructed by the back corner of an automobile, behind which the officer was positioned during the hostage situation standoff. The case highlights a rarely discussed safety rule related to firearms: recognition that the line of sight via a weapon’s sights (or scope) is not identical to the barrel/bore axis.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Hostage, Investigation, Rifle, Homicide

Introduction

Hostage situations present a number of scenarios that can result in gun violence and the loss of life. In these scenarios, police often surround the area where the hostage-taker is located with their hostage(s). While negotiations are sometimes successful and the hostage(s) may be released peacefully, the perpetrator can also commit gun violence against the police, the hostage(s), and/or themselves. Gun violence directed from police toward the perpetrator may also occur, and occasionally, hostages may be the inadvertent victims of police gunfire. The police in these situations are trained to be patient but must act quickly to bring a swift resolution to the situation if an armed perpetrator appears to be in the act of inflicting gun violence. The authors present a hostage situation where a police officer inadvertently shot and killed a hostage.

Case Report

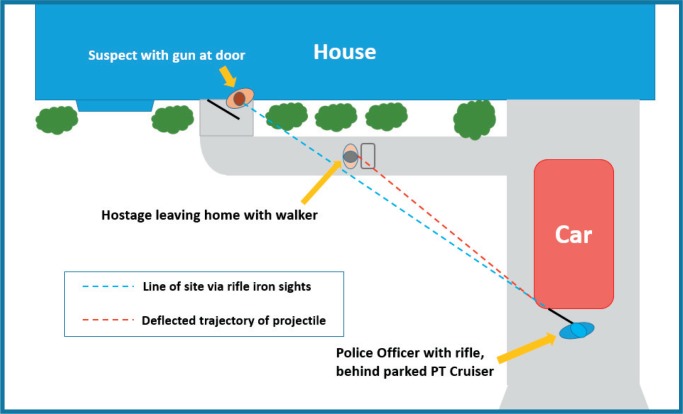

A 74-year-old woman was taken hostage by her ex-husband in his home, where he was reportedly threatening to kill her. After successful police negotiations with the perpetrator, the woman was released by the perpetrator and was exiting the residence via the front door, with her walker, when her ex-husband appeared at the front door brandishing a firearm. A police officer had a Bushmaster .223 caliber rifle trained on the man, and when the man brandished his weapon, the officer fired at him. The man was not hit by the gunfire. Instead, the woman, who was several feet from the front door, walking along a sidewalk parallel to the front of the home, was struck by the projectile, a 55 grain Remington full metal jacket round. She immediately collapsed to the ground. Despite attempts at resuscitation, including transport to the emergency department, she was pronounced dead. In reconstructing the events of the shooting (Figure 1), it was determined that the pathway of the bullet was deflected by an automobile behind which the shooting officer was positioned. The projectile’s trajectory was diverted from its intended target when it perforated the back left region of the automobile (Images 1-5). The officer’s line of sight via the iron sights of the rifle was unobstructed; however, the bore/barrel axis was blocked by the rear of the automobile (Image 6).

Figure 1.

A reconstruction diagram of the event at the time of the shooting.

Image 1.

Photograph of house with walker near where the hostage was hit by police projectile; photograph taken from the perspective of the police shooter.

Image 2.

Photograph of car where police shooter was positioned; photograph taken from the perspective of where the hostage was hit by police projectile.

Image 3.

The back of the vehicle that was interposed between the muzzle end of the police firearm and the target.

Image 4.

Close-up photograph of projectile entrance site on the car.

Image 5.

Close-up photograph of the projectile exit site on the car.

Image 6.

Reconstruction of event that led to projectile being diverted by car. Note that the iron sight (with “w” configuration on top portion of rifle) is not obstructed, whereas the muzzle end of the rifle cannot be seen, as the bore/barrel axis is obstructed by the back of the automobile.

A complete autopsy was performed. On the upper chest, slightly to the left of the suprasternal notch, there was a 5/16-inch × 1/4-inch irregular to crescent-shaped projectile wound, with an irregular marginal abrasion (Images 7 and 8). After perforating the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the chest, the projectile subsequently perforated the sternum, the left subclavian vein, the left subclavian artery, the upper lobe of the left lung, and the posterior aspect of left rib number six before penetrating the soft tissues of the left back. There was approximately 2000 mL of blood within the left chest cavity (Image 9). The deformed, small caliber projectile was recovered from the left back at autopsy (Image 10). Mild to severe atherosclerotic disease of the coronary arteries and aorta was also noted. A urine drug screen was negative, and a blood ethanol level was 244 mg/dL. The cause of death was a rifle wound of the chest. The manner of death (MOD) was homicide.

Image 7.

The location of the chest entrance wound as seen at autopsy.

Image 8.

A close-up view of the chest entrance wound. Note the large, atypical appearance of the wound, consistent with the projectile having traveled through an interposed target prior to striking the victim.

Image 9.

A postmortem chest radiograph, showing a left hemothorax, as well as the projectile, which was recovered from the back.

Image 10.

The recovered projectile.

Discussion

Scene investigation in hostage situations plays a vital role in recreating the events that transpired and resulted in the loss of life, whether it be the hostage-taker, a hostage, a police officer, or a bystander. Collection of evidence, including photography of important aspects of the scene, provides an observational basis by which reconstruction and modeling of the event can take place. As in all cases, evidence collected must be maintained through a chain of custody in order to ensure the authenticity of the data, should the death result in criminal proceedings or a lawsuit.

Hostage situation deaths can vary greatly depending on the situation. These often involve the hostage-taker but may involve hostages as well. One of the most frequent questions in these situations involves identifying the shooter, whether it was the police or the hostage-taker. At autopsy, it is extremely important to determine the range of fire (contact, close, intermediate/medium, or distant/indeterminate), as this may aid in the determination of the shooter’s relative location to the victim. As with any firearm-related death, it is also important to collect the projectiles, so that attempts may be made to match them to a specific weapon.

The MOD in gunshot wound (GSW) deaths can be accident, suicide, homicide, or undetermined (1, 2). In hostage situations in which the hostage-taker dies from a GSW, the MOD considerations are essentially homicide or suicide, where the deadly GSW is inflicted by police or by the hostage-taker, respectively. A contact GSW of the hostage-taker is typically indicative of a suicide (3 –5), although in certain situations where there is direct police contact with the GSW victim, one needs to consider the possibility of execution by police (6). Each case must be evaluated on its own merits. If greater than contact distance, homicide is more likely (3 –5). GSW deaths of hostages, police officers, or bystanders are rightfully ruled as homicides, no matter who fires the fatal shot. Ruling a hostage situation GSW death as an accident is unlikely, although arguments might be made for such a ruling in situations involving a ricochet (see below). Some additional GSW death scenarios where the MOD may be accidental are child shooters, malfunctioning firearms, dropped weapons, animals stepping on the trigger, and certain hunting cases (2), none of which tend to be involved in hostage situations. In certain cases, there may be pressure exerted on the pathologist from police or others to make a ruling of “accident” instead of “homicide.” This is not as likely in GSW cases as it is in police “restraint-associated deaths,” where there can be considerable debate regarding MOD (7, 8). In the case presented, the MOD was determined to be homicide, as the police officer pulled the trigger intending to cause incapacitation of the hostage-taker. An accidental MOD was never considered by the pathologist, as the gun did not malfunction, nor was the gun dropped by the police officer, but instead was purposefully fired, intending to bring an end to the situation. Unfortunately, even though the iron sights showed a clear path to the intended target, the muzzle of the gun was obstructed by the automobile, resulting in the projectile being redirected toward the hostage. The authors acknowledge that some might argue for ruling the MOD as accident in a case such as this; however, by convention and training, we believe that “homicide” is the most appropriate ruling in this case.

Although the shooting presented here does not, strictly speaking, represent a ricochet situation (but instead involves an interposed target), the flight of the projectile was similar to that of a ricocheting projectile. As such, it may be of benefit to briefly review ricochet cases. Ricochet GSW entrance wounds are often irregular in shape (as in the present case), and ricocheted bullets have a decreased likelihood of tissue penetration (9). Gill and Pasquale-Styles mentions ricochet bullets as a consideration when dealing with firearm deaths related to law enforcement (10). In their report of 42 homicides, they do not disclose an exact number of cases involving ricochet, but they do indicate that ricochets are rare, and they imply that they only occurred in the setting of multiple GSWs, with associated fragmentation of projectiles (10).

Reconstruction of a shooting event can provide very useful information when attempting to interpret autopsy and death scene investigation findings. In this case, reconstruction was extremely helpful, as the reenactment (depicted in Image 6) clearly indicated that the muzzle was blocked by the car while the officer’s line of site was unobstructed. In certain instances of scene reconstruction, it may be useful to know or calculate the expected velocity of the discharged projectile, how the bullet’s shape affects its flight, determination of the maximum range of fire for the given ammunition, and other parameters, in order to allow for calculations to be made regarding projectile pathways (11). However, in this case, the deflection produced by the automobile occurred so close to the muzzle as to make such calculations unnecessary and impractical. The muzzle velocity of a .223 (5.56 × 45) 55 grain projectile is reported to be approximately 3150 ft/s (12), and the muzzle was within inches of the automobile at discharge. Thus, there was no appreciable descent of the projectile after discharge prior to interposed target contact, as might happen at much greater lengths of travel. A review of proper firearm safety principles reveals that, had the officer remained diligent in following these principles, this tragic event would likely have been prevented. The accompanying Table 1 lists firearm safety rules, including the classic rules, as well as corollaries (13, 14). One common sense rule is to always treat guns as if they are loaded. This stipulates that the carrier of the firearm always keep the muzzle end of the gun pointed in a safe direction. Second, shooters must keep their finger off the trigger until ready to fire. Third, shooters must be aware of their target and what is beyond/around the target. This last rule is especially important in the present case, where a specific corollary is also worthy of note. Namely, shooters must be aware of the fact that the line of sight (via firearm sights, scopes, etc) is not exactly the same as the bore/barrel axis line. Particularly when there is a significant distance between the sight axis and bore/barrel axis, shooters must recognize that what is seen as a “clear shot” via the sights (or scope) does not necessarily translate into a “clear shot” from the standpoint of potential muzzle obstruction.

Table 1.

| Major Safety Rules |

| Always treat firearms as if they are loaded. |

| Keep finger off of trigger until ready to fire. |

| Know your target and what is beyond. |

| Corollary Rules |

| Prior to attempting to discharge a firearm, the user should know how to operate it and ensure that the weapon is mechanically sound. |

| A clear shot via a scope/sight does not necessarily correlate to a clear shot from the muzzle. |

| Never use alcohol or other debilitating drugs or substances before or while shooting. |

| Only use ammunition designed for the firearm in use. |

| Wear ear and eye protection as appropriate. |

| Store guns so that they are not accessible to unauthorized persons. |

| Ammunition should be stored separately from the firearm. |

| Be aware that some guns and many shooting activities require additional safety precautions. |

| Regular cleaning of firearms is important for firearms to operate correctly and safely. |

Conclusion

Hostage situation deaths require a thorough investigation and collaboration between death investigators, police, and forensic pathologists. Only through well-documented scene findings and autopsy results can accurate conclusions be reached and the death certificate completed appropriately. Because of the intense nature of hostage situations, split-second decisions sometimes result in tragic outcomes. It is incumbent upon all firearms users, including law enforcement personnel, to always be aware of potential safety issues when using a firearm. In this case, had the officer remained diligent in following all firearm safety principles by ensuring that the muzzle end and bore/barrel axis of the weapon were not blocked by an interposed target, this tragic event would likely have been prevented.

Authors

Samuel P. Prahlow MPH, Florida State University

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, principal investigator of the current study.

Joseph A. Prahlow MD, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine - Pathology

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, general supervision, general administrative support, writing assistance and/or technical editing.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

Statement of Informed Consent: No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscript

Disclosures & Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1). Hanzlick R, Hunsaker JC, Davis GJ. A guide for manner of death classification [Internet]. Marceline (MO): National Association of Medical Examiners; 2002; [cited 2016 Oct 26]. 29 p. Available from: https://netforum.avectra.com/public/temp/ClientImages/NAME/4bd6187f-d329-4948-84dd-3d6fe6b48f4d.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2). Hanzlick R. A perspective: gun-related fatalities and manner of death. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2013. June; 3(2):171–82. 10.23907/2013.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Molina DK, DiMaio VJM, Cave R. Handgun wounds: a review of range and location as pertaining to manner of death. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2013. December; 34(4):342–7. PMID: 24189632 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Molina DK, DiMaio V, Cave R. Gunshot wounds: a review of firearm type, range, and location as pertaining to manner of death. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2013. December; 34(4):366–71. PMID: 24196728 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Cave R, DiMaio VJ, Molina DK. Homicide or suicide? Gunshot wound interpretation: a Bayesian approach. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2014. June; 35(2):118–23. PMID: 24781397 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Karger B, Billeb E, Koops R, Brinkmann B. Autopsy features relevant for discrimination between suicidal and homicidal gunshot injuries. Int J Legal Med. 2002. October; 116(5):273–8. PMID: 12376836 10.1007/s00414-002-0325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Gill JR, Girela-López E. Manner of death for in-custody fatalities. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2015. September; 5(3):402–13. 10.23907/2015.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Graham M. Investigations of deaths temporally associated with law enforcement apprehension. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2014. September; 4(3): 366–89. 10.23907/2014.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Yong YE. A systematic review on richochet gunshot injuries. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2017. May; 26:45–51. PMID: 28549547 10.1016/j.legalmed.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Gill JR, Pasquale-Styles M. Firearm deaths by law enforcement. J Forensic Sci. 2009. January; 54(1):185–8. PMID: 19040676 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Warlow TA. Firearms, the law and forensic ballistics. Bristol (PA): Taylor & Francis Ltd; c1996 Chapter 6, External ballistics and cartridge loadings; p. 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- 12). DiMaio VJM. Gunshot wounds: practical aspects of firearms, ballistics, and forensic techniques. 3rd ed Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016. 355 p. [Google Scholar]

- 13). Prahlow JA. Fatal gunshot wounds in young children. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2016. December; 6(4):691–702. PMID: 31239941 PMCID: PMC6474487 10.23907/2016.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). NRA Explore [Internet]. Fairfax (VA): National Rifle Association; c2018 NRA Gun safety rules; [cited 2018 Sep 17]. Available from: http://training.nra.org/nra-gun-safety-rules.aspx. [Google Scholar]