Abstract

Background and objective

The true posterior communicating artery (TPCoA) aneurysms are rare and endovascular treatment for such lesions is limited in literature.

Methods

From January 2012 to March 2017, eight TPCoA aneurysms were treated endovascularly and included in our present study. The procedural complication and outcomes were assessed.

Results

Seven of eight aneurysms (87.5%) were ruptured. Stent-assisted coiling was used in one case that a stent was deployed via PCoA-ipsilateral P2 segment. The dual-microcatheter technique was used in one case. The remaining six cases were treated by coiling alone. One patient (12.5%) suffered perioperative complication, of which a coil herniated into parent vessel during the procedure without symptomatic stroke or other adverse event after the procedure. The initial embolization results showed complete occlusion in five cases and residual neck in three. Six patients (75%) had a mean of 15-month angiographic follow-up and two of them revealed recurrence (33.3%). Clinical follow-up was available in seven patients (87.5%) and all patients showed favorable clinical outcome with mRS score 0.

Conclusion

TPCoA aneurysms are rare and challenging lesions with high rupture rate in literatures. Endovascular treatment may be a feasible alternative for TPCoA aneurysms. Primary coiling, as well as adjunctive strategies, such as stent-assisted coiling or dual catheter techniques may be considered. Further study in a larger population is necessary.

Keywords: Posterior communicating artery aneurysm, rupture, stent-assisted coiling, endovascular treatment, dual-microcatheter technique

Introduction

True posterior communicating artery (TPCoA) aneurysms are defined as aneurysms arising from the PCoA itself rather than the junction of the internal carotid artery (ICA) and the PCoA.1,2 These aneurysms represent about 1.3% of all intracranial aneurysms and 6.8% of all PCoA aneurysms.1 Some studies suggest that this subtype of aneurysms is more prone to rupture.1–3

Some of the authors prefer microsurgical management to endovascular treatment because of difficulty in navigation of microcatheter and potential risk of intraoperative rupture.1,4–8 However, microsurgical clipping for such lesions also maintains challenges due to anatomic complexity.3,4,6–10 Although advances in endovascular devices and techniques have revolutionized the management of complex aneurysms, the feasibility and efficacy of these methods in managing TPCoA aneurysms are yet to be determined. In particular, the intrinsic location of the aneurysm neck, the high prevalence of anatomical PComm variants and shear size of the vessel pose unique challenges.

Given the low incidence of TPCoA aneurysms, only limited small endovascular experiences are available in the literature.11–19 To the best of our knowledge, only 19 total endovascularly treated cases are published in the literature with only six cases followed angiographically. The safety and efficacy of endovascular therapy for TPCoA aneurysm are still unclear based on limited cases. Therefore, in our present study, we demonstrate our experience in endovascular management of eight patients with eight TPCoA aneurysms.

Materials and methods

Patient population

From January 2012 to March 2017, 13 patients with 13 TPCoA aneurysms were diagnosed by digital subtraction angiography (DSA) in our hospital. Twelve aneurysms (92.3%) were ruptured. Of these cases, eight TPCoA aneurysms were treated endovascularly and included in our present study. Approved by the institutional review board, the medical records of these patients were reviewed to collect demographic, clinical, and radiological information. Morphological characteristics, including aneurysm size, neck size, aneurysm shape, size ratio (aneurysm size divided by parent vessel size, SR), and aspect ratio (aneurysm size divided by neck size, AR), were obtained and measured in three-dimensional (3D) angiographic images. Hunt and Hess grade was used for evaluating patients with ruptured aneurysms. Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores were collected for all patients before the treatment and discharge. Radiographic results were categorized using Raymond et al.20 scale: complete occlusion, residual neck, and residual aneurysm. A recurrence was defined as any increase in the size of the remnant. The follow-up was performed with angiographic examination, preferably DSA. Clinical outcomes were measured by mRS at time of follow-up angiography or by telephone interview.

Endovascular treatment

Treatment modality, such as coiling alone, dual-microcatheter coiling or stent-assisted coiling, is decided by three experienced neurointerventionists after careful evaluation of patients’ clinical condition and vascular anatomical features. Most of the cases included in the present study were ruptured and only one was unruptured. For ruptured TPCoA aneurysms, coiling alone is preferred or dual-microcatheter coiling is considered if the aneurysm neck is unfavorable. Stent-assisted coiling is also considered to be used in aneurysms with unfavorable neck (neck > 4 mm or dome-neck ratio <2) and it is also considered if the vascular anatomic relation is applicable with sufficient vascular diameter and less tortuous arterial course. For some instance, the stent may deploy via ipsilateral P1-PcomA-distal ICA (retrograde stenting) or via PcomA-ipsilateral P2.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The clinical and imaging characteristics of the included cases are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Of the eight patients, there were six women and two men, with a mean age of 48.6 years (range 41–58 years). Two cases had smoking history without hypertension and six patients showed hypertension without smoking. Seven of eight aneurysms (87.5%) were ruptured and six of the ruptured aneurysms were treated within 72 h. The Hunt-Hess grade was 3 in one patient, 2 in two patients and 1 in four patients. Before treatment, mRS score was 4 in two patients, 1 in five patients and 0 in one patient.

Table 1.

The clinical characteristics of the patients with true PCoA aneurysms.

| No. | Age | HTN | Smoke | Presentation | Hunt and Hess | Pre-mRS | Treatment strategy | Angiographic result | Complication | mRS at discharge | Angiographic FU/months | mRS at clinical FU/months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 40–45 | Yes | No | SAH within 72 h | 2 | 1 | Coiling | RN | No | 1 | R/3/DSA | 0/3 | |

| Case 2 | 50–55 | No | Yes | SAH within 8 h | 3 | 4 | DMC | RN | No | 1 | S/6/CTA | 0/23 | |

| Case 3 | 40–45 | Yes | No | SAH within 22 h | 1 | 4 | Coiling | CO | No | 0 | – | 0/20 | |

| Case 4 | 55–60 | Yes | No | SAH within 24 h | 2 | 1 | Coiling | CO | Coil herniation | 1 | S/36/DSA | 0/36 | |

| Case 5 | 50–55 | Yes | No | SAH after 1 month | 1 | 0 | Coiling | CO | No | 0 | R/13.5/DSA | 0/13.5 | |

| Case 6 | 50–55 | Yes | No | SAH within 6 h | 1 | 1 | Coiling | CO | No | 1 | – | – | |

| Case 7 | 40–45 | No | Yes | Blurred vision 1 month | 0 | 1 | SAC | CO | No | 0 | S/26/DSA | 0/26 | |

| Case 8 | 45–50 | Yes | No | SAH within 8 h | 1 | 1 | Coiling | RN | No | 1 | S/5.3/DSA | 0/5.3 | |

PCoA: posterior communicating artery; F: female; M: male; HTN: hypertension; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage; Pre-mRS: modified Rankin Scale before treatment; FU: follow up; DMC: dual-microcatheter coiling; SAC: stent-assisted coiling; CO: complete occlusion; RN: residual neck; R: recurrent; S: stable.

Table 2.

The morphological characteristics of the true PCoA aneurysms.

| No. | Location | Aneurysm size, mm | Neck size, mm | SR | AR | Daughter bleb | Dome projection | Ipsilateral P1 segment exist | Multiple aneurysms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Left proximal PCoA | 6.1 | 1.9 | 4.04 | 3.21 | Yes | Superior-posterior | No | No |

| Case 2 | Left proximal PCoA | 5.9 | 2.6 | 1.63 | 2.27 | No | Superior | No | No |

| Case 3 | Right proximal PCoA | 4.6 | 2.6 | 2.24 | 1.77 | No | Inferior | Yes | No |

| Case 4 | Left proximal PCoA | 5.3 | 3.2 | 1.94 | 1.66 | Yes | Inferior | Yes | Yes |

| Case 5 | Left proximal PCoA | 6.3 | 3.1 | 3.15 | 2.03 | No | Superior-posterior | Yes | No |

| Case 6 | Left proximal PCoA | 3.8 | 2.3 | 1.77 | 1.65 | Yes | Superior | Yes | No |

| Case 7 | Left distal PCoA | 10.5 | 7.1 | 4.57 | 1.48 | No | Lateral | Yes | No |

| Case 8 | Right proximal PCoA | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.16 | 1.36 | Yes | Superior-posterior | Yes | No |

PCoA: posterior communicating artery; SR: size ratio; AR: aspect ratio.

The mean aneurysm size, neck size, SR, and AR were 5.6 mm (range 2.3–10.5 mm), 3.1 mm (range 1.7–7.1 mm), 2.56 (range 1.16–4.57), and 1.93 (range 1.36–3.21), respectively. Three of the aneurysms showed irregular shape with daughter blebs. All seven ruptured aneurysms were located at proximal segment of PCoA and the unruptured aneurysm (case 7) was originated at distal segment of PCoA.

Procedure and complication

In the present study, one case (case 7, Figure 1) was treated by stent-assisted coiling with stent deployment from the PCoA to ipsilateral P2. The dual-microcatheter technique was used in one case which was embolized by coils via two microcatheters alternately (case 2). The remaining cases were treated with coil alone.

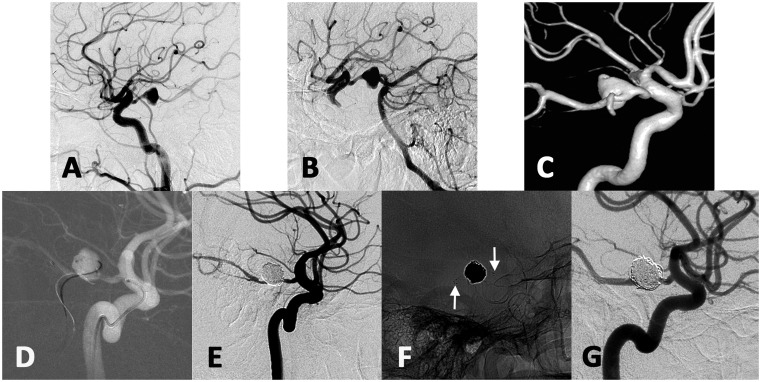

Figure 1.

The left internal carotid artery angiogram showed a 10.5 mm aneurysm arising from the distal segment of left PCoA (a). Left vertebral angiography with carotid compression showed the aneurysm via posterior communicating artery (b). Three-dimensional vascular reconstruction showed the aneurysm (c). The stent-microcatheter was navigated from left ICA-PCoA and delivered into PCA. Another microcatheter was introduced over micro-guidewire from left vertebral artery and navigated into the aneurysm (d). Final angiogram showed the aneurysm was complete occlusion by stent-assisted coiling (e). The white arrows showed the two ends of the stent (f). The aneurysm showed complete occlusion with PCoA patency at 26-month angiographic follow-up (g).

One perioperative complication occurred (12.5%, case 4) with coil herniation to the parent vessel, though no symptomatic stroke resulted. The initial embolization results showed complete occlusion in five cases (cases 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7) and residual neck in three (cases 1, 2, and 8). All of the patients showed good recovery at discharge (mRS 1 in five patients and 0 in three patients).

Outcome

In our study, six patients (75%; cases 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8) had a mean of 15-month angiographic follow-up (range, 3–36 months) and two of them revealed recurrence (33.3%; case 1 and case 5). Angiographic follow-up of these two cases showed coil compactions and both cases displayed an increasing percentage of contrast filling the aneurysmal neck. No retreatment was performed in the cases because of the technical difficulty in endovascular performance and the stable status based on results from additional follow-ups. Clinical follow-up was available in seven patients (87.5%) at a mean of 17.5 months and all patients showed favorable clinical outcome with mRS score 0.

Illustrative cases

Case 7

This 41-year-old man presented with blurred vision and left oculomotor nerve palsy for a month. DSA showed a 10.5 mm unruptured aneurysm arising from the distal segment of left PCoA (Figure 1). The aneurysm neck was 7.1 mm with dome-neck ratio 1.48 and the parent artery diameter was 2.3 mm. Three-dimensional angiography showed that the initiation of the PCoA was less torturous. Therefore, stent-assisted coiling was used in this case. Considering the small size of the parent vessel (PCoA was 2.3 mm), we thought there might be difficulty in navigating two micro-catheters in the PCoA following the same route of ICA-PCoA-PCA. Therefore, after general anesthesia and bilateral femoral sheaths placement, two guiding catheters were introduced respectively into left ICA and left vertebral artery. The stent-microcatheter was navigated from left ICA-PCoA and delivered into PCA. Then, the microcatheter with proper tip shape was introduced over micro-guidewire from left vertebral artery and navigated into the aneurysm. After sufficient coil embolization, an Enterprise stent (Cordis Neurovascular, Miami, FL, USA) was deployed from the P2 segment to the PCoA with post-intervention angiography showing complete occlusion of the aneurysm. Enterprise is a self-expandable and retractable device. This stent could be used in the vessel from 2.5 to 4.5 mm and the PCoA is about 2.3 mm in this case. Post-procedure course was uneventful. The aneurysm showed complete occlusion with PCoA patency at 26-month angiographic follow-up.

Discussion

TPCoA aneurysms, as aneurysms originating from PCoA itself, are extremely rare.1 The literature on endovascular management of such lesions is limited and the angiographic follow-up rate is considerably lower (Table 3).11–19 We retrospectively reviewed a series of eight TPCoA aneurysms in our database to assess the safety and efficacy of endovascular treatment in such cases. In this study, most of the treated TPCoA aneurysms were ruptured (7/8, 85.7%). Endovascular treatment is a feasible alternative for TPCoA aneurysms with careful evaluation before the procedure. Adjunctive techniques, such as stent-assisted coiling, could be considered for elective cases.

Table 3.

The published cases of true PCoA aneurysm under endovascular treatment.

| Author(s) and Reference no. | Sample size | Rupture/ unrupture | Operation | Complication | Angiographic outcome | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kubo et al.16 | 1 | 1/0 | 1 coiling | None | 3-month DSA/ complete obliteration | Full recovery |

| Meguro et al.15 | 1 | 1/0 | 1 coiling | Multiple cerebral infarctions caused by vasospasm | 7-month DSA/ complete obliteration | Full recovery |

| Park et al.14 | 1 | 0/1 | 1 coiling | None | 12-month DSA/ stable | mRS 0 |

| Guo et al.11 | 3 | 3/0 | 2 coiling | None | – | – |

| Munarriz et al.12 | 1 | 0/1 | 1 coiling | None | 6-month MRA/ stable | Marked improvement |

| Almeida-Perez et al.17 | 1 | 0/1 | 1 coiling | None | – | – |

| Yang et al.13 | 9 | 9/0 | 8 coiling/ 1 SAC | None | – | GOS five in all cases |

| Mitsuhashi et al.18 | 1 | 1/0 | 1 PAO | None | 1-month DSA/ complete obliteration | Well recovery |

| Yang et al.19 | 1 | 1/0 | 1 SAC | None | 9-month DSA/ stable | mRS 0 |

| Total | 19 | 16/3 | 15 coiling/ 2 SAC/ 1 PAO | 1 ischemic event | 6 cases had FU with stable or complete occlusion | 15 cases had FU with favorable outcome |

SAC: stent-assisted coiling; PAO: parent artery occlusion; FU: follow-up.

PCoA aneurysms, traditionally arising at the junction of ICA and PCoA, account for approximately 25% of all intracranial aneurysms.3 It is reported that PCoA aneurysms are more likely to rupture than aneurysms at other locations.3,21 For the TPCoA aneurysms, the rupture risk is reported to be even higher (44 of 49, 89.8%).2,3 Consistent with the limited literature, seven of eight cases (85.7%) in our study were ruptured. Successful and effective managements of these patients are crucial in preventing against re-rupture and subsequent mortality.

Nowadays, endovascular treatment has been widely used in management of intracranial aneurysms and such strategy in managing TPCoA aneurysms is reported in a few case studies.11–19 Munarriz et al.12 reported a case of successful endovascular coiling of a TPCoA aneurysm with subsequent angiographic stability. Another report from Guo et al.11 showed three such aneurysms, of which two were treated endovascularly without complications. However, the angiographic outcomes were unknown from their data. Parent artery occlusion with coils was also reported as an endovascular alternative in a case report.18 A study13 with nine ruptured TPCoA aneurysms was published. In their study, seven cases were completely embolized and two cases were near-completely occluded after initial treatment. All the patients showed good clinical outcome; however, their angiographic outcomes were unknown. In addition, the group reported a case treated by stent-assisted coiling though no details or images were available for reference and guidance.

As reported in the literature, microsurgical clipping for TPCoA aneurysms is traditionally preferred.1,4 However, the neurovascular anatomy of the PCoA is complex.3,4,9,10 The perforating arteries arising from PCoA supply the optic chiasm, oculomotor nerve, anterior thalamus, hypothalamus, and internal capsule. Therefore, care must be taken to avoid compromising the blood flow to PCoA during clipping of such lesions. Additionally, the oculomotor nerve typically comes laterally to PCoA and preservation of such nerve is also important.10,22 Thus, microsurgical clipping of TPCoA aneurysms is still full of challenges and the potential risk of microsurgical clipping should be evaluated carefully.5,6,8,9,23,24 Endovascular treatment should be considered as an alternative in aneurysms not amenable to microsurgical clipping, patients with high anesthesia/surgical risk or in cases with endovascularly favorable anatomy. A thorough understanding of aneurysm location and configuration is essential in successful treatment of these lesions. With the aid of 3D rotational angiography, preoperative aneurysm anatomy could be accurately evaluated, making it ideal for microcatheter navigation and embolization. Other authors noted the difficulty in navigating the microcatheter into these aneurysms, especially those with inferior dome configuration which lend themselves to higher intraoperative rupture risk.1,12 In our series, the microcatheter could be successfully introduced after appropriately tip shaping and no intraoperative rupture occurred in our cases. As with any other location, wide-neck aneurysms can be challenging and require adjunctive techniques such as stent-assisted coiling or dual microcatheter guidance. However, for TPCoA aneurysms, the vascular anatomic relationship is much more complex and those techniques may not be applicable to every case. Therefore, it may be difficult to achieve dense packing for some of the cases and therefore the risk of coil herniation may be higher as demonstrated in our series. Subsequently, the recurrence rate of TPCoA aneurysm without complete occlusion or dense packing will be higher. That may be the reason why the recurrence rate was 33.3% in our study. No retreatment was performed in our two recurrent cases because of the technical difficulty in endovascular performance and the stable status based on results from additional follow-ups. Importantly, in ruptured cased with SAH-treated endovascularly, there was no re-rupture events and 87.5% of these patients had a favorable clinical outcome. Therefore, endovascular treatment is still an effective therapy for patients with TPCoA aneurysms.

Young et al.25 reported two PCoA aneurysms treated with retrograde stent placement from the terminal ICA to PCoA. Yang et al.19 showed a stent-assisted coiling case with the proximal end of the stent protruded into the fetal PCA. It seems to be a good alternative for TPCoA aneurysms treatment. However, as the author indicated, such technique should be reserved for those cases with specific vascular anatomy. In our study, we demonstrated a case treated by stent-assisted coiling. Although this endovascular strategy is successful for our case, some anatomic requirements in P1, P2, PCoA, and ICA were needed before stent-assisted coiling. Briefly, in order to deploy the stent, the micro-catheter needs to be navigated via the PCoA. In some circumstances, the origin curve of the PCoA is too sharp to navigate the micro-catheter. Therefore, the vascular anatomy needs to be considered before the stent-assisted coiling. What’s more, the new stent device, such as Neuroform Atlas or LVIS Jr., may be a better choice for stent-assisted coiling of wide necked TPCoA aneurysm. The procedure may be much easier as the newer devices could be delivered through a lower profile micro-catheter.26 Meanwhile, most of the TPCoA aneurysms are ruptured and anti-platelet medication may increase potential risk of hemorrhage in treatment with stent. The safety and efficacy of this treatment strategy need to be assessed with larger population.

The main limitation of present study is that the sample size is small. Although, the efficacy of endovascular treatment of TPCoA aneurysms could not be concluded with such limited angiographic follow-up data, endovascular treatment may be still effective in preventing re-rupture of ruptured TPCoA aneurysm and 87.5% patients showed favorable clinical outcome. The rupture risk of TPCoA aneurysms should be also validated by a larger sample study. There are some other limitations, such as retrospective design, selection bias, treatment bias and lack of a comparison group of surgical clipping. Multicenter and high-volume analysis of embolization treatment for TPCoA aneurysm is still needed in the future.

Conclusion

TPCoA aneurysms are rare and challenging lesions with high rupture rate in literatures. Endovascular treatment may be a feasible alternative for TPCoA aneurysms. Primary coiling, as well as adjunctive strategies, such as stent-assisted coiling or dual catheter techniques may be considered. Further study in a larger population is necessary.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: supported by National Key Research and Development Plan of China (grant number: 2016YFC1300800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 81801156, 81801158, 81471167 and 81671139), the Special Research Project for Capital Health Development (grant number: 2018-4-1077) and Beijing Hospitals Authority Youth Programme, code: QML20190503.

References

- 1.He W, Gandhi CD, Quinn J, et al. True aneurysms of the posterior communicating artery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. World Neurosurg 2011; 75: 64–72. discussion 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He W, Hauptman J, Pasupuleti L, et al. True posterior communicating artery aneurysms: are they more prone to rupture? A biomorphometric analysis. J Neurosurg 2010; 112: 611–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golshani K, Ferrell A, Zomorodi A, et al. A review of the management of posterior communicating artery aneurysms in the modern era. Surg Neurol Int 2010; 1: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuzmik GA, Bulsara KR. Microsurgical clipping of true posterior communicating artery aneurysms. Acta Neurochir 2012; 154: 1707–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nery B, Araujo R, Burjaili B, et al. True posterior communicating aneurysms: three cases, three strategies. Surg Neurol Int 2016; 7: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mochizuki Y, Kawashima A, Yamaguch K, et al. Thrombosed giant “true” posterior communicating artery aneurysm treated by trapping and thrombectomy. Asian J Neurosurg 2017; 12: 757–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeda M, Kashimura H, Chida K, et al. Microsurgical clipping for the true posterior communicating artery aneurysm in the distal portion of the posterior communicating artery. Surg Neurol Int 2015; 6: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y, Meng X, Song J, et al. Microsurgical treatment of ruptured true posterior communicating artery aneurysm in the distal portion of the posterior communicating artery. J Craniofac Surg 2019; 30: e5–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorimachi T, Fujii Y, Nashimoto T. A true posterior communicating artery aneurysm: variations in the relationship between the posterior communicating artery and the oculomotor nerve. Case illustration. J Neurosurg 2004; 100: 353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vincentelli F, Caruso G, Grisoli F, et al. Microsurgical anatomy of the cisternal course of the perforating branches of the posterior communicating artery. Neurosurgery 1990; 26: 824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo J, Chen Q, Miao H, et al. True posterior communicating artery aneurysms with or without increased flow dynamical stress: report of three cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2014; 116: 93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munarriz PM, Castano-Leon AM, Cepeda S, et al. Endovascular treatment of a true posterior communicating artery aneurysm. Surg Neurol Int 2014; 5: S447–S450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, Su W, Meng Q. Endovascular treatment of ruptured true posterior communicating artery aneurysms. Turkish Neurosurg 2015; 25: 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yung Ki P, Hyoung-Joon C, Young-Jun L. Endovascular embolization of a de novo true posterior communicating artery aneurysm 23 years after surgical clipping of an ipsilateral posterior communicating artery-internal carotid artery aneurysm: a case report. Kor J Cerebrovasc Surg 2011; 13: 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meguro T, Terada K, Hirotune N, et al. [A case of ruptured true posterior communicating artery aneurysm with neurogenic pulmonary edema treated early by GDC embolization]. No Shinkei Geka 2005; 33: 1001–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubo M, Kuwayama N, Hirashima Y, et al. Endovascular treatment of unusual multiple aneurysms of the internal carotid artery-posterior communicating artery complex – case report. Neurol Med Chir 2000; 40: 476–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Almeida-Perez R, Espinosa-Garcia H, Alcala-Cerra G, et al. [Endovascular coiling of a <<true>> posterior communicating artery aneurysm]. Neurocirugia 2014; 25: 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitsuhashi T, Takeda N, Oishi H, et al. Parent artery occlusion for ruptured “true” posterior communicating artery aneurysm. Int Neuroradiol 2015; 21: 171–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang ZG, Liu J, Ge J, et al. A novel proximal end stenting technique for assisting embolization of a complex true posterior communicating aneurysm. J Clin Neurosci 2016; 28: 148–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raymond J, Guilbert F, Weill A, et al. Long-term angiographic recurrences after selective endovascular treatment of aneurysms with detachable coils. Stroke 2003; 34: 1398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forget TR, Jr., Benitez R, Veznedaroglu E, et al. A review of size and location of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2001; 49: 1322–1325. discussion 1325–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bisaria KK. Anomalies of the posterior communicating artery and their potential clinical significance. J Neurosurg 1984; 60: 572–576. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kudo T. An operative complication in a patient with a true posterior communicating artery aneurysm: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1990; 27: 650–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakano Y, Saito T, Yamamoto J, et al. Surgical treatment for a ruptured true posterior communicating artery aneurysm arising on the fetal-type posterior communicating artery–two case reports and review of the literature. J UOEH 2011; 33: 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho YD, Kim KM, Lee WJ, et al. Retrograde stenting through the posterior cerebral artery in coil embolization of the posterior communicating artery aneurysm. Neuroradiology 2013; 55: 733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Stenting after coiling using a single microcatheter for treatment of ruptured intracranial fusiform aneurysms with parent arteries less than 1.5 mm in diameter. World Neurosurg 2017; 99: 809.e7–809.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]