Abstract

PURPOSE

To improve cancer outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people through the development and national endorsement of the first population-specific optimal care pathway (OCP) to guide the delivery of high-quality, culturally appropriate, and evidence-based cancer care.

METHODS

An iterative methodology was undertaken over a 2-year period, and more than 70 organizations and individuals from diverse cultural, geographic, and sectorial backgrounds provided input. Cancer Australia reviewed experiences of care and the evidence base and undertook national public consultation with the Indigenous health sector and community, health professionals, and professional colleges. Critical to the OCP development was the leadership of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health experts and consumers.

RESULTS

The OCP received unanimous endorsement by all federal, state, and territory health ministers. Key elements of the OCP include attention to the cultural appropriateness of the health care environment; improvement in cross-cultural communication; relationship building with local community; optimization of health literacy; recognition of men’s and women’s business; and the need to use culturally appropriate resources. The OCP can be used as a tool for health services and health professionals to identify gaps in current cancer services and to inform quality improvement initiatives across all aspects of the care pathway.

CONCLUSION

The development of the OCP identified a number of areas that require prioritization. Ensuring culturally safe and accessible health services is essential to support early presentation and diagnosis. Multidisciplinary treatment planning and patient-centered care are required for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, irrespective of location. Health planners and governments acknowledge the imperative for change and have expressed strong commitment to work with Indigenous Australians to improve the accessibility, cultural appropriateness, and quality of cancer care.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a leading cause of death across the world, and Indigenous populations carry a substantial and increasing cancer burden.1 Despite these trends, cancer in Indigenous populations has largely been overlooked.2

Although Australia’s cancer survival rates overall are among the best in the world,3 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience disparities in cancer incidence and outcomes. In 2011 to 2015, cancer was the second leading cause of death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.4 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were 40% more likely to die as a result of cancer than non-Indigenous Australians.5 In 2010 to 2014, the 5-year observed survival rate for all cancers combined was 48% for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people—substantially lower than that for non-Indigenous Australians (59%).6

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a different pattern of cancer incidence: some cancers occur more commonly than among non-Indigenous Australians.7 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a higher incidence of cancers that are preventable (eg, cervical and head and neck cancers), and are more likely to be fatal (eg, lung and liver cancers).7,8 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people also face higher risk factors for cancer. For instance, the smoking rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people age 18 years or older is approximately 41% compared with approximately 15% in non-Indigenous Australians.9 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people also have higher levels of other modifiable risk factors for cancer, including obesity, lack of physical activity, risky levels of alcohol consumption, and high rates of hepatitis B and C infections.10-16

In addition, participation rates in national breast, cervical, and bowel cancer screening programs are generally lower among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people,17-20 and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are generally more likely than other Australians to be diagnosed with cancer (except for prostate cancer) at an advanced stage of disease.6,21 These disparities in cancer incidence and outcomes may be due in part to the existence of comorbidities or to poorer access to health care services because of financial, language, cultural, or geographic barriers.15,16,22-24 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are less likely to be hospitalized for cancer care.15 The impact of unconscious or implicit bias from service providers is particularly detrimental and can perpetuate health inequities experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.25

Cancer Australia is the Australian Government agency established to provide leadership in national cancer control. Cancer Australia has identified Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cancer control as a priority and has acknowledged the importance of leading a shared agenda to address the unwarranted variations in Indigenous cancer outcomes. Cancer Australia established the Leadership Group on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Control (Leadership Group) as a strategic advisory group to bring together leaders of influence in Indigenous health, research, and policy as well as consumers affected by cancer. The Leadership Group has evolved over time to build a national conversation about cancer, has informed the sector about the increasing cancer burden experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities, and has guided and influenced service and system change.

In 2015, Cancer Australia developed an evidence-based, nationally agreed-upon strategic framework to guide future Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cancer control efforts. The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework identifies seven priorities that would have the greatest impact on disparities in cancer outcomes. Priority five is to “ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people affected by cancer receive optimal and culturally appropriate treatment, services, and supportive and palliative care.”10

The distinct epidemiology of cancer among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their unique connection to culture highlighted the need for a focus to develop guidance for services and health professionals on the delivery of culturally safe and responsive health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Cancer Australia has taken the successful Australian model of tumor-specific optimal care pathways26 and developed, for the first time, a population-based pathway, the Optimal Care Pathway (OPC) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer. Optimal cancer care pathways describe the key steps in a patient’s cancer journey and the expected standards of care at each stage to improve patient outcomes for all people diagnosed with cancer, regardless of where they live or receive cancer treatment.27

This paper describes the development process of this ground-breaking OCP, which is a pragmatic guide to care delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. An iterative methodology was undertaken over a 2-year period with a literature review to inform the drafting of the OCP and with broad input at key stages from more than 70 organizations and individuals from diverse cultural, geographic, and sectorial backgrounds. The engagement process provides a valuable model to develop policy that considers the contexts of those most affected, and it is informed by health service planners and providers who can help drive change at both service and system levels.

METHODS

Governance

The development of the OCP was an initiative of Cancer Australia as part of the National Cancer Work Plan of the National Cancer Expert Reference Group (NCERG). Established by the Council of Australian Governments in 2011, NCERG brings together jurisdictional representatives with cancer experts and consumers to take forward key initiatives that address disparities in cancer outcomes across different groups as well as more effective cancer diagnosis, treatment, and referral protocols.

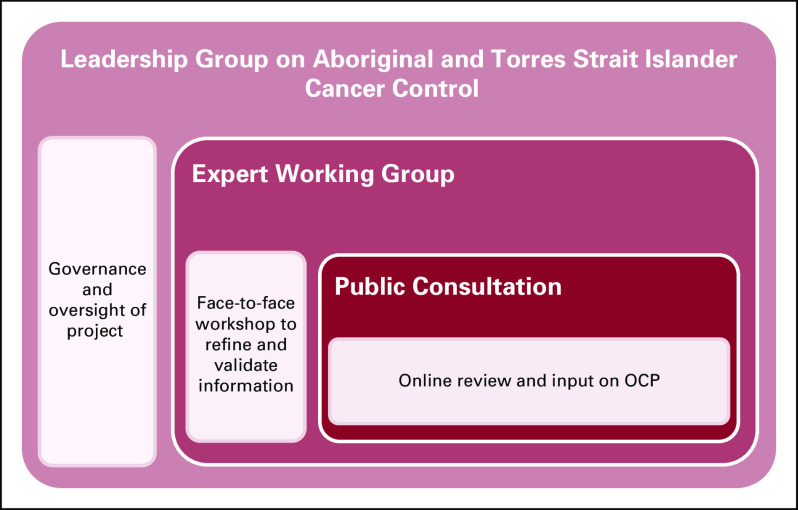

The OCP project steering committee, chaired by Robert Thomas, OAM, comprises clinical, consumer, and health policy representation and has guided the development of all OCPs. The Cancer Australia Leadership Group provided strategic guidance and oversight throughout the development of the OCP. An overview of consultation and governance is depicted in Figure 1.

FIG 1.

Overview of consultation and governance. OCP, Optimal Care Pathway.

OCP Development

Cancer Australia partnered with the Victorian state Department of Health and Human Services to lead the development of the OCP and to coordinate cross-jurisdictional input and endorsement. The evidence review and drafting of the OCP were undertaken in collaboration with Cancer Council Victoria, an agency with significant experience in drafting tumor-specific OCPs.

The three main research activities conducted to develop the OCP were as follows: a review of the available evidence; stakeholder consultation and input; and synthesis of the evidence and feedback to develop the OCP.

Review of evidence.

A desktop literature review was undertaken to identify the key considerations for the delivery of culturally safe and responsive care across the continuum for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer. The literature review was undertaken between October 2016 and January 2017 and examined the evidence that informed the development of the Cancer Australia National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework10 (Framework) and recent English-language, peer-reviewed publications. During the Framework development, peer review databases—including Informit, OVID, IPortal, EBSCOhost, Cochrane library, Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar—were searched between December 2014 and February 2015. The key search terms were broad and related to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cancer (specific terms were as follows: Aborigin* or Torres Strait* or ATSI or Oceanic Ancestry Group and cancer or malignan* or tumo$r* or oncology or neoplasm*). The review also included targeted searches of contemporary gray literature, such as jurisdictional policy documents, medical college reports, conference presentations and abstracts, and relevant standards of care. The literature review specifically sought to identify any barriers to optimal care based on the experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to ensure that the OCP addressed these areas of concern. On the basis of this evidence, an initial draft of the OCP was developed.

Stakeholder consultation and input.

Genuine engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, communities, and organizations was critical to the OCP development, whose efforts are central to improvement in cancer outcomes for Indigenous Australians. A stakeholder mapping process was undertaken to ensure that all relevant stakeholders were engaged. Consultation was undertaken in two ways: (1) engagement of a multidisciplinary expert working group (EWG) to refine and validate the initial draft of the OCP at a 1-day, face-to-face workshop and (2) subsequent inquiry into the views of a broad range of stakeholders on a refined draft by e-mail. Community engagement and collaboration, information exchange, and sustainability were hallmarks of Cancer Australia’s engagement process.

Health professionals, researchers, community members affected by cancer and representatives from all government jurisdictions were invited to participate in the EWG. The EWG comprised 23 members, and more than 50% of members identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.

The EWG co-chairs, Jacinta Elston and William Glasson, AO, facilitated detailed discussion among members to refine and validate the OCP. Members considered the appropriateness of the language as well as the tone and cultural information, identified any gaps in the content, considered the accuracy of the medical information, and suggested appropriate additional resources. The EWG also considered the importance of reflecting the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, their needs, and their preferences.

After EWG engagement, input, and agreement, an online national public consultation was conducted during a 7-week period to obtain broad input into the content and structure of the OCP. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peak health bodies, medical colleges, organizations, associations, health professionals, and consumers were invited to participate in this national consultation process. Specifically, feedback was sought on current evidence and practice in the provision of culturally safe, high-quality, and evidence-based cancer care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The consultation received 36 submissions from national peak bodies, professional associations, federal government departments, state-based cancer organizations, state government departments, local service providers, primary health networks, academics, and individuals. Submissions to the national public consultation were reviewed and synthesized, and these informed the finalization of the OCP.

Final drafting of the OCP.

After the evidence review and stakeholder consultations, an iterative approach was used to identify the key inclusions in the draft OCP. This involved synthesis of new evidence, EWG input, and refinement of the draft based on specific feedback from the broader stakeholder consultation.

The project team collated and synthesized priority themes, and they accounted for contextual issues that related to health and cancer care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the social determinants and cultural determinants of health, and Australia’s multifaceted health care system. The EWG and the Leadership Group were actively consulted on the content and revisions of the draft OCP to draw upon the expert knowledge and experience of the members.

The Leadership Group informed the development of the final draft through confirmation of key themes, appropriate messaging, and audience, and this group confirmed the importance of measuring the impact of the OCP. Input was provided on the development of the supporting resources: a quick reference guide for health professionals as well as consumer guides for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people undergoing tests for suspected cancer and for those who have received a cancer diagnosis. Importantly, the draft consumer guides were focus tested in diverse Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and revised according to feedback.

RESULTS

The OCP incorporated the pathway steps and key principles of optimal care that are outlined in all tumor-specific OCPs.

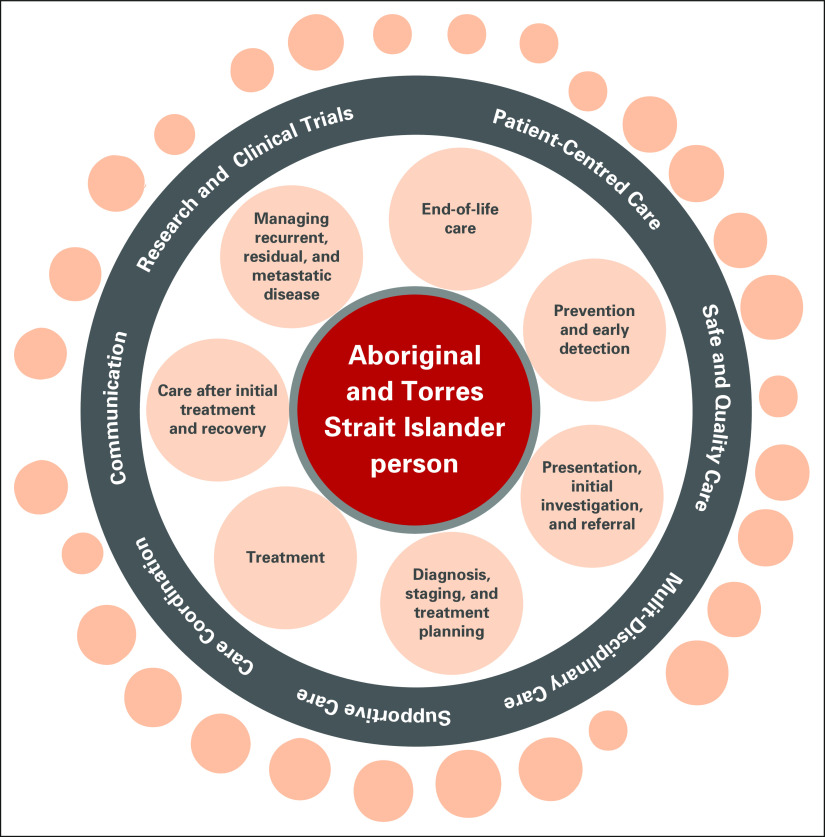

The principles of optimal care are as follows: patient-centered care, safe and quality care, multidisciplinary care, supportive care, care coordination, communication, and research and clinical trials. The steps and principles were contextualized for application by health services and health professionals who work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. An example of contextualization of the principle of patient-centered care is acknowledgment of the philosophies of holistic health and well-being.28 Consultation feedback influenced the fundamental conceptualization of the original linear pathway to one in which the patient is consistently the center of care (Fig 2).

FIG 2.

Optimal Care Pathway (OCP) principles and steps.

An introductory section about how to support the delivery of optimal care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer was developed to provide information and guidance on the practical application of the principles across the cancer continuum. Key elements of this section include attention to the cultural safety of the health care environment; improvement in cross-cultural communication; relationship building with local community; optimization of health literacy; recognition of men’s and women’s business; and the need to use culturally appropriate resources. The extensive consultation of the OCP also identified the importance of inclusion and support of family and carers using culturally appropriate supportive care needs assessment and provision and noted the value of inclusion of an expert in provision of culturally appropriate care in the patient’s multidisciplinary care team. This expert may be an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health worker, health practitioner, or hospital liaison officer.

The OCP can be used as a tool for health services and health professionals to identify gaps in current cancer services and to inform quality improvement initiatives across all aspects of the care pathway. Clinicians also can use the OCP as an information resource and tool to promote discussion and collaboration between health professionals and people affected by cancer.

The OCP received unanimous endorsement by NCERG and all jurisdictional health ministers through the Council of Australian Governments Health Council. As part of this endorsement process, health ministers discussed initiatives to improve health care and achieve equity in health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Health ministers acknowledged the significant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership in the development of the OCP.

DISCUSSION

The tumor-specific OCPs provided the basis for development of an evidence-based optimal care pathway for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, a population of diverse cultures who experience significant disparities in cancer outcomes. The development characteristics of this OCP are in line with the ASCO Criteria for High-Quality Pathways in Oncology; it has a shared agenda for change, and it transparently details in the Foreword how stakeholder input was reflected.29

The policy leadership of well-respected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders brought credibility to the process, strengthening engagement and, ultimately, buy-in to emerging national policy. This combination of input and leadership has been a unique aspect of the development of this OCP, distinct from the tumor-specific OCPs, which were clinician-led.

The diagnostic and treatment pathway for cancer is complex and involves multiple health professionals across a range of public and private settings. Although the clinical aspects of optimal care are the same for all people, ensuring the pathway is culturally safe and responsive is vital to address the disparities in outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer. A key component to achieve this is by building consciousness among health professionals and health services about implicit bias and a deeper understanding about how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer can be supported in the delivery of care. There is an imperative for the health system to work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to design and deliver integrated, culturally appropriate care across the patient pathway and to empower the patient to understand and inform their treatment choices.

There is strong, tangible commitment across sectors to implement change. The development process highlighted a range of activities already initiated by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled health sector, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, innovative health and cancer services, health professionals, and government agencies. All health ministers unanimously endorsed the final OCP and are now looking at opportunities for investment to support sustainable improvements across the health sector, including strengthened cultural safety capability, Indigenous-led health research, and growth in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce. The collaborative effort and engagement in the process of developing this OCP has strengthened the momentum to implement best-practice, culturally appropriate care that will improve cancer outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

It was clear through the development of the OCP that a number of areas require prioritization. There is a need for health units and practitioners to improve the cultural safety of their services, particularly at the primary health care level to support early presentation and diagnosis. Multidisciplinary treatment planning and patient-centered care are required for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, irrespective of location. Greater efforts could be directed to successfully integrate care across services and to address practical, psychological, and cultural needs to support the continuation of treatment. This is particularly important when treatment needs to occur away from home. The inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professionals and liaison officers in care planning and delivery, supported by all governments, will go some way to improve the quality of communication and the accessibility and completion of treatment.

Cancer Australia is collaborating across sectors with cross-jurisdictional cancer experts to set in motion the development of a national strategy to support uptake of the OCP. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people must remain at the center of this process to inform on design and delivery. Development of practical approaches to measure change at population and system levels also will be critical to the success of OCP implementation. Next steps for the OCP focus on promotion of uptake of the pathway and implementation of priority action so that Australia can see improvements in cancer outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Throughout the OCP development process, there were strong intentions to engage with all key stakeholders across the country. However, some limitations must be acknowledged. The national online consultation could have been strengthened to encourage more communities and organizations to participate in consultation. The process could have been improved through broader and earlier engagement with stakeholders, including face-to-face consultation when resources were available.

In conclusion, the development of the OCP involved a comprehensive, iterative process to analyze inputs and synthesize key elements of best-practice care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer. Consultation across a diverse range of stakeholders was critical to canvass different perspectives and inform the iterative development of this pathway.

This paper outlines the development of a specific pathway to improve cancer outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. However, the planning and methodology described could have wider application for the development of national policy initiatives, both within Australia and internationally. Although the collection of knowledge and views of a diverse range of stakeholders has its challenges, this highly consultative approach has the benefit of fostering ownership and targeted action for those who have the levers to drive change.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the following: NSW Breast Partners Forum, Sydney, Australia, February 5, 2018; Cancer Nurses Society of Australia Annual Congress 2018, Brisbane, Australia, June 23, 2018; Cancer Institute NSW Innovations in Cancer Treatment and Care Conference 2018, Sydney, Australia, September 13, 2018; World Cancer Congress, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, October 1-4, 2018; Clinical Oncology Society of Australia Annual Scientific Meeting 2018, Perth, Australia, November 12, 2018; Optimal Care Pathway National Workshop, Melbourne, Australia, May 8, 2019; and Gynecologic Oncology Network: Nursing and Allied Health Seminar Day, Sydney, Australia, May 24, 2019.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jennifer Chynoweth, Meaghan M. McCambridge, Helen M. Zorbas, Jacinta K. Elston, William J.H. Glasson, Joanna M. Coutts, Barbara A. Daveson, Kathryn M. Whitfield

Collection and assembly of data: Jennifer Chynoweth, Meaghan M. McCambridge, Helen M. Zorbas, Robert J.S. Thomas, William J.H. Glasson, Joanna M. Coutts, Barbara A. Daveson, Kathryn M. Whitfield

Data analysis and interpretation: Jennifer Chynoweth, Meaghan M. McCambridge, Helen M. Zorbas, Joanna M. Coutts, Barbara A. Daveson, Kathryn M. Whitfield

Administrative support: Jacinta K. Elston, Kathryn M. Whitfield

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jgo/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Jennifer Chynoweth

Consulting or Advisory Role: Allergenis (I)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Allergenis (I)

Joanna M. Coutts

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Medibank Private

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brands J, Garvey G, Anderson K, et al. Development of a national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cancer framework: A shared process to guide effective policy and practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:942. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15050942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris B, Smart G, Moore S, et al. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/575e13942b8ddeb3fba54b8a/t/58a294bfcd0f68d988b3d29f/1487049941200/WICC+Post+Conference+Report+Aug2016.pdf World Indigenous Cancer Conference 2016 post-conference report.

- 3.Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): Analysis of individual records for 37,513,025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391:1023–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33326-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council . Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework 2017 report. Canberra, Australia: Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Cancer in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Australia. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-in-indigenous-australians/contents/ [PubMed]

- 6.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Cancer in Australia 2019. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-in-australia-2019/contents/table-of-contents. [Google Scholar]

- 7.CancerAustralia Cancer incidence. https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/diagnosis/cancer-incidence/cancer-incidence

- 8.CancerAustralia Cancer mortality. https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/outcomes/cancer-mortality/cancer-mortality

- 9.CancerAustralia Smoking prevalence: Adults. https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/prevention/smoking-prevelance/smoking-prevalence-adults

- 10.CancerAustralia National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cancer framework. https://canceraustralia.gov.au/publications-and-resources/cancer-australia-publications/national-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-cancer-framework

- 11.Haigh M, Burns J, Potter C, et al. Review of cancer among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Aust Indigen Health Bull. 2018;18 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham J, Rumbold AR, Zhang X, et al. Incidence, aetiology, and outcomes of cancer in indigenous peoples in Australia. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:585–595. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System Annual Report Working Group Australia’s notifiable disease status, 2014: Annual report of the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2016;40:E48–E145. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2016.40.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Kirby Institute . Bloodborne viral and sexually transmitted infections in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: Annual surveillance report 2018. Sydney, Australia: The Kirby Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-health-welfare/health-performance-framework-new/contents/tier-1-health-status-outcomes Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework (HPF) report.

- 16.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIWH) Australia’s Health 2018 (catalog No. AUS 221). Canberra, Australia: AIHW; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIWH) National Bowel Cancer Screening Program: Monitoring Report 2018 (catalog No. CAN 112) Canberra, Australia: AIHW; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cancer Australia https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/screening/breast-screening-rates/breast-screening-rates Breast screening rates.

- 19.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIWH) Cervical Screening in Australia 2019 (catalog No. CAN 124) Canberra, Australia: AIHW; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whop LJ, Garvey G, Baade P, et al. The first comprehensive report on indigenous Australian women’s inequalities in cervical screening: A retrospective registry cohort study in Queensland, Australia (2000-2011) Cancer. 2016;122:1560–1569. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cancer Australia https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/diagnosis/distribution-cancer-stage/distribution-cancer-stage Distribution of cancer stage.

- 22.Gurney J, Sarfati D, Stanley J. The impact of patient comorbidity on cancer stage at diagnosis. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:1375–1380. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li JL. Cultural barriers lead to inequitable healthcare access for aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders. Clin Nurs Res. 2017;4:207–210. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amery R. Recognising the communication gap in indigenous health care. Med J Aust. 2017;207:13–15. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson AM, Kelly J, Magarey A, et al. Working at the interface in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health: Focussing on the individual health professional and their organisation as a means to address health equity. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15:187. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0476-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viner AH, Williams-Spence JM, Whitfield KT, et al. Optimal cancer care pathways: Developing best practice guides to improve patient outcomes and identify variations in care. Australian Journal of Cancer Nursing. 2016;17:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Australian Government Department of Health Optimal Cancer Care Pathways (OCPs) http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/occp

- 28.Cancer Australia . Optimal care pathway for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer. https://canceraustralia.gov.au/publications-and-resources/cancer-australia-publications/optimal-care-pathway-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people-cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daly B, Zon RT, Page RD, et al. Oncology clinical pathways: Charting the landscape of pathway providers. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e194–e200. doi: 10.1200/JOP.17.00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]