Abstract

PURPOSE

Conflict-induced cross-border travel for medical treatment is commonly observed in the Middle East. There has been little research conducted on the financial impact this has on patients with cancer or on how cancer centers can adapt their services to meet the needs of this population. This study examines the experience of Iraqi patients seeking care in Lebanon, aiming to understand the social and financial contexts of conflict-related cross-border travel for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

After institutional review board approval, 60 Iraqi patients and caregivers seeking cancer care at a major tertiary referral center in Lebanon were interviewed.

RESULTS

Fifty-four respondents (90%) reported high levels of financial distress. Patients relied on the sale of possessions (48%), the sale of homes (30%), and vast networks to raise funds for treatment. Thematic analysis revealed several key drivers for undergoing cross-border treatment, including the conflict-driven exodus of Iraqi oncology specialists; the destruction of hospitals or road blockages; referrals by Iraqi physicians to Lebanese hospitals; the geographic proximity of Lebanon; and the lack of diagnostic equipment, radiotherapy machines, and reliable provision of chemotherapy in Iraqi hospitals.

CONCLUSION

As a phenomenon distinct from medical tourism, conflict-related deficiencies in health care at home force patients with limited financial resources to undergo cancer treatment in neighboring countries. We highlight the importance of shared decision making and consider the unique socioeconomic status of this population of patients when planning treatment.

INTRODUCTION

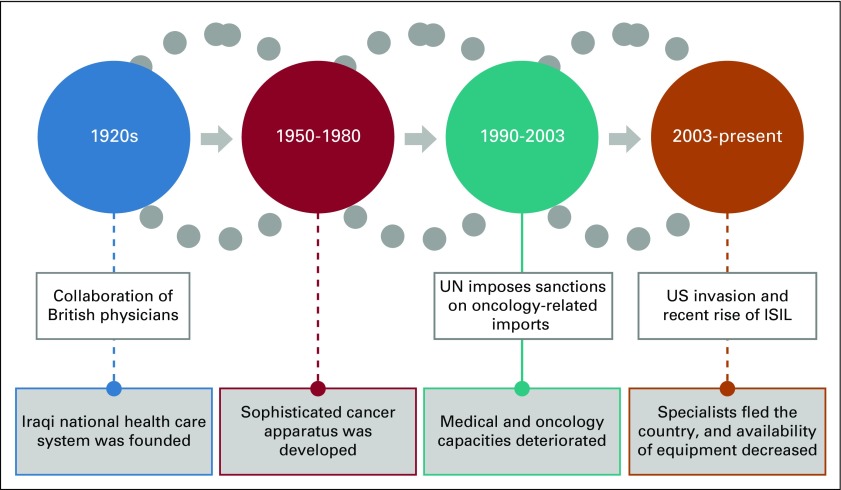

The impact of conflict on access to cancer treatment is particularly complex in the Middle East. Formerly robust health care systems in countries such as Iraq have witnessed deterioration under the weight of urban warfare, economic embargos, and the loss of medical personnel.1,2 One consequence of this has been the rise of cross-border trajectories of care. A growing number of patients split treatment between local and cross-border medical centers in Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, Iran, and India.3 Figure 1 summarizes the chronology of cancer care and challenges faced in Iraq.

FIG 1.

Chronology of cancer care development in Iraq. ISIL, Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant; UN, United Nations.

In the years after the US invasion (2003 to present), physicians have been forced to operate under immense sectarian pressures and amid episodes of violence,4 a significant number of specialists have fled the country.5 Efforts to rebuild the medical and oncology infrastructures have generated important projects,6 but serious challenges remain.7,8

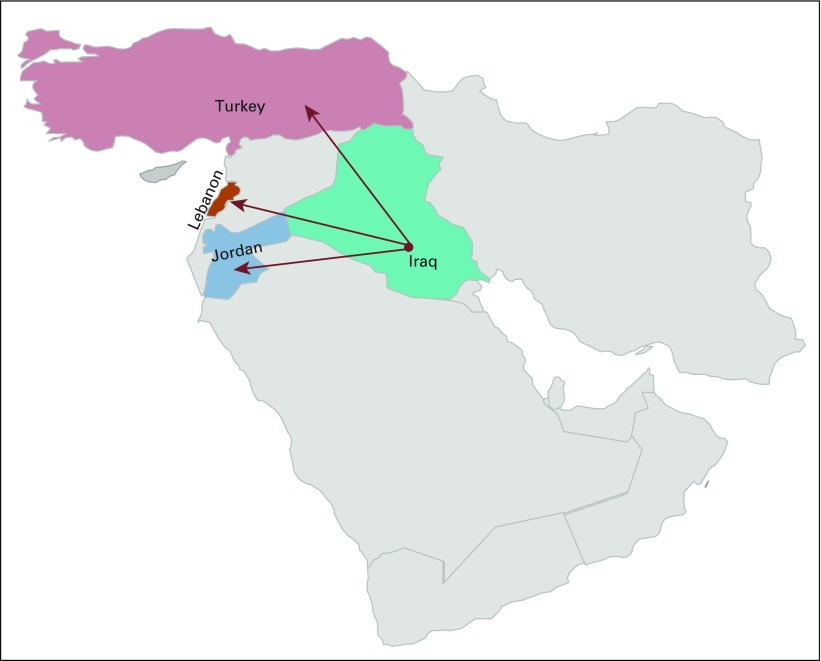

The more recent rise of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and anti-ISIL militias has further complicated access to oncology centers in Iraq.9 Although the official campaign against ISIL ended during the time between data collection and publication of this report, millions remain displaced, and a wide array of armed groups continues to occupy significant territory. Many oncology centers in the territories previously occupied by ISIL remain nonoperational. The loosening of border controls since 2003 has given patients alternative options for cancer diagnosis and treatment in neighboring countries. Oncology centers in the region have seen huge increases in the number of nonrefugee Iraqi patients with cancer who remain permanent residents of Iraq while traveling back and forth for health care (Fig 2).

FIG 2.

Iraqi cross-border travel for cancer care. Regional geography: Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey have become hubs for patients from Iraq seeking cancer care.

This study examines the experience of Iraqi patients with cancer seeking care in Lebanon through the lens of one such oncology hub, the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC). The aim of this study was to understand experiences of care in the social and financial contexts of conflict-related cross-border travel for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

After institutional review board (IRB) approval, adult Iraqi patients attending the private clinics at AUBMC were recruited for interviews through the display of flyers in clinic reception and chemotherapy treatment areas. Patients or caregivers interested in participating initiated contact with the research team and were asked to provide written informed consent for interviews and review of medical records. The interviews were conducted in Arabic by a member of the research team (M.Skelton) and included quantitative and qualitative questions on motivations for traveling to Lebanon, experiences of care, and social and financial circumstances. It is worth noting that the timing of the study coincided with the final months of the war against ISIL, by which many patients in the sample were directly or indirectly affected. Qualitative data from the surveys were reviewed and thematically analyzed by M.S., R.A., and D.M. For background epidemiologic data regarding the population of patients seeking cancer care at AUBMC, the diagnoses of adult patients with cancer with Iraqi nationality were retrospectively reviewed with IRB approval from January 2013 to December 2016. The inclusion of this retrospective data was important to emphasize the scale and broader contours of this cross-border phenomenon beyond the participants interviewed.

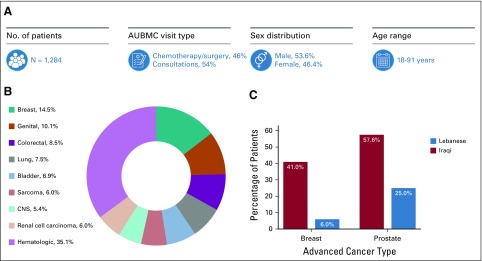

RESULTS

For the prospective sample, data from 60 patients and caregivers were collected, comprising 24 men and 36 women, with a median age of 49 years. All 60 respondents answered a mixed-methods qualitative and quantitative questionnaire. Forty-nine patients gave approval to access of medical records; the diagnoses and staging of these 49 patients are outlined in Figure 3, whereas the remaining data pertain to the full set of 60 respondents.

FIG 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients responding to prospective questionnaire. (A) Demographic and staging information. (B) Diagnosis/tumor type. ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia.

Financial Pressures and Strategies

Fifty-four respondents (90%) reported high levels of financial distress associated with paying for treatment in Lebanon. More than half (n = 35) of the respondents reported a monthly household income in the US$0 to US$1,000 range, 16 reported an income between US$1,000 and $2,000, and only 9 reported an income > US$2,000. For patients who had made 1 to 4 visits to Lebanon for cancer treatment, US$20,531 was the average total expenditure for treatment, board, tickets, food, and so on. For patients making ≥ 5 visits, US$98,852 was the average expenditure. The gap between income and expenditure over multiple trips forced patients and families to make difficult decisions around treatment. One caregiver of an elderly male patient who had already made 9 trips to Lebanon explained: “Today my father has decided he won’t do the necessary surgery in Lebanon, and maybe we’ll go back to do it in Baghdad, so that we don’t keep having to go back and forth constantly and to cut down on expenditures.”

Because none of the respondents possessed private health insurance covering treatment in Beirut, they drew on a combination of household income and other sources, such as the sale of possessions, raising of money through donations, and taking on debt. A vast majority of respondents reported an inability to pay for treatment with household income (54 of 60), and a significant portion drew on extended networks (43 of 60) and the sale of homes (18 of 60) to fund treatment trips. The reasons given for insufficient income (qualitative) were as follows: rising cost of living since 2003; difficulty in accessing a job; ransoms or death threats to owners of businesses, leading to job loss; displacement from origin and separation from income-earning networks; and destruction of income-generating farm equipment or land because of conflict.

Patterns of Mobility

Patients were asked to detail their place of residence and provinces/locations of all treatment sites to track patterns of mobility and access. Twenty-five reported residence in Baghdad, and 28 reported residence in the provinces south of the capital (eg, Basra, Najaf). Seven patients reported their original residence in the provinces directly affected by ISIL violence (eg, Mosul, Anbar, Salahadin, Diyala, Kirkuk); these 7 patients were displaced and temporarily residing elsewhere, largely in the semiautonomous Kurdistan region (eg, Erbil, Dohuk, Sulaymaniyah). Across the 60 respondents, the primary finding was that patients usually managed chemotherapy through back-and-forth travel between Iraq and Lebanon as opposed to taking up long-term residence in Beirut. Many added that this was a cost-saving measure resulting from the high daily rates of hotels and associated costs in Beirut. Most were traveling back and forth every 14 to 20 days according to chemotherapy schedules.

Cyclic international travel.

Patients (55 of 60) reported a pattern of regular back-and-forth travel between Iraq and Lebanon (or, among new visitors, an intention to do so); only a handful (5 of 60) reported semipermanent residence in Beirut.

Aligning visits with chemotherapy.

Respondents reported 3- to 7-day stays in Lebanon for chemotherapy, after which they would return to Iraq until the next treatment.

Total number of visits.

The study population included 10 first-time visitors; 21 respondents had visited Lebanon 2 to 5 times; 17 had visited 6 to 10 times; 13 had visited ≥ 11 times; 1 patient with rectal cancer had made 40 discrete visits to Lebanon.

Interprovincial travel.

Before coming to Lebanon for an initial visit, interprovincial care seeking across Iraqi regions was a widely shared practice (27 of 60) because of the shifting conditions of war, finances, and access to hospitals.

Experiences and Drivers of Cross-Border Treatment

All 60 patients in the prospective sample were asked a number of quantitative questions as well as open-ended qualitative questions on the value, quality, and reasons for seeking treatment across an international border. In the quantitative section, a majority of the patients rated the overall experience of treatment in Lebanese hospitals highly. Likewise, the provision of quality treatment, nursing, and social support was rated highly (49 of 60). The only moderate to low ratings pertained to the physician-patient sharing of information, with nearly half (27 of 60) rating their experience poorly in this regard.

In the qualitative section, patients described their reasons for coming to Beirut in the context of a deterioration of care in Iraq, particularly calling attention to the exodus of specialists after 2003.6 They described a lack of access to care as a result of either immediate conditions of violence or long-term deterioration of health care institutions. To detail the primary drivers of cross-border treatment, we list the top 5 themes from the thematic analysis of qualitative results (Fig 4).

FIG 4.

Drivers of cross-border treatment from Iraq to Lebanon (thematic analysis of qualitative results). AUBMC, American University of Beirut Medical Center.

Human resources.

All respondents saw the conflict-driven exodus of Iraqi physicians since 2003 as a hugely significant event, leading to overworked and under-resourced medical staff. In their experience, hospital staff in Beirut were, in contrast, able to devote more time and attention to patients.

Therapeutic and diagnostic shortages.

Respondents frequently stated that, although technically free of charge in public hospitals, chemotherapy agents in Iraq were only sporadically available. Patients traveled across provinces to a given hospital only to find that drugs were not available. Linear accelerators were reported to be extremely scarce throughout Iraq, with long wait times in the few cities with working machines. Respondents referred to the lack of modern diagnostic machines, particularly positron emission tomography (PET)–computed tomography scans. A patient with breast cancer from Baghdad explained: “Machines are unavailable in Iraq. Mammography is not clear. PET is not available. We don’t trust the chemotherapy.”

Destroyed facilities and blocked roads.

Some respondents noted how oncology centers were damaged in the central/northern areas of Iraq because of ISIL and/or militia violence, or access to them was cut off. The cutting off of major northern roadways affected not only patients from the ISIL-occupied territories but also those from Baghdad, who partially relied on treatment in the relatively strong oncology centers of Erbil and Sulaymaniyah and could no longer access the Kurdish region by car. One patient noted: “Now I have to fly to Erbil if I want treatment, just like I have to fly to Beirut. So it’s better to just come here!”

Visa regulations and proximity.

Respondents understood Lebanese visa regulations to be more lax than those of Jordan, Turkey, or India. Respondents noted the small fee for the entry visas provided in the Beirut airport (US$40) and the 1-hour plane ride from Iraq were essential in choosing Lebanon as a treatment destination.

Recommendations/referrals.

Networks of family and friends with previous experience at AUBMC served as informal referrals. Respondents also mentioned physician referrals. One woman with breast cancer said the following: “The chemotherapy in Iraq was okay, but the doctor said that hospitals in Beirut would be able to handle the side effects better.” In some cases, these referrals were more direct and personal. An Iraqi oncologist would mention the name of the specific oncologist to be visited in Lebanon.

In addition to discussing the drivers of cross-border treatment, respondents addressed the following country-specific factors contributing to high levels of financial distress.

War- and displacement-related financial hardship in Iraq.

The overall cost of cancer care is compounded by the broader financial hardships of life under conflict in Iraq. The 7 respondents from the central/northern territories occupied by ISIL reported losses of homes and farming equipment as a result of displacement. One displaced businessman who underwent bone marrow transplantation at AUBMC noted: “I used to be the owner of a factory in Anbar, but ISIL destroyed it, so I now live in Sulaymaniyah without income, and I cannot work there. I’ve paid $250,000 and sold my house for treatment, and now I can’t even fund a $2,000 trip to Lebanon for a checkup without asking a friend for money.”

Conflict economy.

Although not all provinces of Iraq are affected directly by ISIL-related violence, respondents from all areas complained of a war economy in which militias and political parties control local job markets and demand payments from small businesses.

High costs of and structural barriers to long-term planning in Lebanon.

Respondents reported that costs in Lebanon accrued unpredictably and without warning. One woman with breast cancer, whose family had already sold a house and land, had just received news of a change in cost structure: “We switched types of chemotherapy today and now it’s $4,000 instead of $1,800, so we are sitting here just staring at each other.” Iraqi families struggle to access information on long-term costs of treatment, which creates a knowledge deficit exacerbated by a pay-as-you-go accounting system that issues bills at the time of each visit rather than in cumulative packages. In the Iraq of the post-2003 era, patients have gradually become accustomed to purchasing high-cost cancer pharmaceuticals when unavailable in Iraqi public hospitals; however, services such as inpatient hospital stays and consultations remain either free in public hospitals or relatively inexpensive in private centers, so patients are shocked about the high cost of these services in Lebanon.

Disease Profiles and Demographics of Iraqi Patients With Cancer Presenting to AUBMC

The 60 patient cases comprising the prospective data fall within a larger population of Iraqi patients with cancer across dozens of Beirut hospitals, the size and scale of which remain unknown. To understand the scale of this cross-border phenomenon, we analyzed the disease profile of Iraqi patients with cancer presenting to AUBMC between 2013 and 2016. Patients with Iraqi nationality accounted for approximately 20% of patients included in the AUBMC institutional tumor registry annually (data summarized in Fig 5). Of these, 46% received chemotherapy or underwent surgery at AUBMC, whereas 54% presented for consultations only; 60% presented with localized disease, and 40% presented with advanced disease. Of Iraqi patients presenting with breast cancer, 41% presented to AUBMC with advanced disease (v approximately 6% of Lebanese patients who are diagnosed with stage IV disease).10 Data from patients with prostate cancer have shown that 25% of Lebanese patients present with advanced disease, compared with 57.6% of patients from Iraq who are treated at AUBMC.11

FIG 5.

Demographic and disease profile characteristics of Iraqi patients treated at the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC) from 2013 to 2016. (A) Demographic and clinical information. (B) Tumor type distribution. (C) Lebanese or Iraqi patients diagnosed with advanced breast or prostate cancer at AUBMC.

DISCUSSION

Iraqi patients with cancer travel domestically and internationally both for security reasons and to undergo treatments that are not available locally. This study examines the international dimension of this phenomenon through the lens of a regional oncology hub in Lebanon. Our data from a prospective sample of 60 patients provide a glimpse into the medical and economic dimensions of seeking cancer care under conditions of war in Iraq. In general, treatment-related costs vastly exceeded monthly household incomes, forcing patients to sell homes and property, with 90% of respondents reporting high levels of financial distress. Thematic analysis revealed several key drivers for undergoing cross-border treatment, including the conflict-driven exodus of Iraqi oncology specialists; the destruction of hospitals or road blockages; referrals by Iraqi physicians to Lebanese hospitals; the geographic proximity of Lebanon; and the lack of diagnostic equipment, radiotherapy machines, and reliable provision of chemotherapy in Iraq.

To put the data in a broader context, we reviewed the clinical diagnoses and staging of patients of Iraqi origin presenting to our center, which showed a high prevalence of advanced disease at diagnosis (Fig 5). Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size recruited from a single private health care institution. From our discussions with the 20% of patients of Iraqi origin presenting to us annually, we have become aware that financial toxicity is a common complaint but were surprised by the high prevalence of financial distress reported. The provision of quality treatment, nursing, and social support was highly rated by our respondents; however, physician-patient sharing of information was identified as an area for improvement that has direct implications for financial planning.

Health care across borders, typically labeled as medical tourism, is often conceptualized as low cost. Researchers have lauded the potential of countries in the Middle East region, such as Tunisia, to serve nearby European populations seeking private health care economically. Lautier12 and Kangas13 have forwarded an important counter of this model, arguing that inequalities within the Middle East leave patients from resource-poor countries, such as Yemen, no choice but to seek burdensome health care in medium- to high-income countries, such as those in the Gulf region.

Financial toxicity is a relatively recent term for a highly prevalent problem.14 With the exponential rise in the cost of cancer therapeutics, oncologists are becoming increasingly involved in these discussions.15 A recent systematic review of methods for measuring financial toxicity after cancer diagnosis identified a lack of consensus.16 Several instruments have been proposed, such as the COST measure, which has been validated in the United States but may not be relevant to patients in different health care settings.17

Ubel et al18 have argued in favor of the full disclosure of finances by oncologists. In the context of war, where costs accumulate for factors beyond treatment alone, it is essential for patients to be given the tools needed to make long-term financial plans. Given that most Iraqis seeking care in Lebanon are self-paying, without insurance, financial counseling includes informing the patient about the cost and expected duration of treatment and the need for sustainability in financial resources. In addition, we propose forming partnerships between Lebanese and Iraqi oncology institutions and improving communication for shared clinical decision-making. Disseminating the publicly available drug costs to Iraqi partners would provide a starting point for financial advice.

As a more general point, oncologists in Lebanon must take into account the specific social circumstances of these patients and understand the broader context of war-related socioeconomic hardship, recognizing that these patients are forced to seek care across borders.19,20 A broad collaboration between the Iraqi and Lebanese governments to address the clinical needs and financial deficits faced by Iraqi patents seeking medical care in Lebanon is the subject of ongoing efforts.

In conclusion, conflict-related deficiencies in health care at home force patients with limited financial resources to undergo cancer treatment in neighboring countries. We have identified high levels of financial distress among our patients traveling from Iraq to receive cancer care in Beirut. Providing information about the expected outcome, duration, and cost of treatment can empower them to engage in shared decision making and better financial planning. With the escalating costs of newly approved cancer treatments, we need to reframe our appraisal of value in cancer care within the socioeconomic context and be able to effectively communicate this information to patients. From a global oncology perspective, we should be aware that patients seeking cancer care across borders from conflict-affected regions represent a war-affected population with specific needs.

Footnotes

Presented as a poster at the 54th ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, June 1-5, 2018.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Mac Skelton, Raafat Alameddine, Omran Saifi, Miza Hammoud, Maya Zorkot, Sally Temraz, Ali Shamseddine, Kazim F. Namiq, Omar Dewachi, Deborah Mukherji

Administrative support: Raafat Alameddine, Maya Charafeddine, Talar Telvizian, Deborah Mukherji

Provision of study material or patients: Ali Shamseddine, Mohammed Saleem, Kazim F. Namiq

Collection and assembly of data: Mac Skelton, Raafat Alameddine, Omran Saifi, Miza Hammoud, Maya Zorkot, Marilyne Daher, Maya Charafeddine, Mohammed Saleem, Kazim F. Namiq, Deborah Mukherji

Data analysis and interpretation: Mac Skelton, Raafat Alameddine, Omran Saifi, Miza Hammoud, Maya Zorkot, Ali Shamseddine, Layth Mula-Hussain, Kazim F. Namiq, Ghassan Abu Sitta, Zahi Abdul-Sater, Talar Telvizian, Walid Faraj, Deborah Mukherji

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Sally Temraz

Honoraria: Merck Sharp & Dohme

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Amgen, Merck

Ali Shamseddine

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer

Speakers’ Bureau: Novartis, Sanofi, Merck, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Amgen, Bayer, Pfizer

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Amgen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck, Algorithm

Kadhim F. Namiq

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck Sharp & Dohme Oncology

Deborah Mukherji

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck Sharp & Dohme Oncology, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astellas Pharma

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Merck Serono (Inst), Novartis (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Amgen, Merck Serono

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dewachi O, Skelton M, Nguyen VK, et al. Changing therapeutic geographies of the Iraqi and Syrian wars. Lancet. 2014;383:449–457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sikora K. Cancer services are suffering in Iraq. BMJ. 1999;318:203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7177.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewachi O, Rizk A, Singh NV. (Dis)connectivities in wartime: The therapeutic geographies of Iraqi healthcare-seeking in Lebanon. Glob Public Health. 2018;13:288–297. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2017.1395469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alwan N, Kerr D. Cancer control in war-torn Iraq. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:291–292. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnham GM, Lafta R, Doocy S. Doctors leaving 12 tertiary hospitals in Iraq, 2004-2007. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hadad S, Al-Jadiry MF. Future planning to upgrade the pediatric oncology service in the Baghdad children welfare teaching hospital. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(suppl 1):S19–S20. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318249ab50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dewachi O: Ungovernable Life: Mandatory Medicine and Statecraft in Iraq. Palo Alto, CA, Stanford University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mula-Hussain L: Cancer Care in Iraq: A Descriptive Study. Riga, Latvia, LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skelton M, Mula-Hussain LYI, Namiq KF. Oncology in Iraq’s Kurdish region: Navigating cancer, war, and displacement. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–4. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.008193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Saghir NS, Assi HA, Jaber SM, et al. Outcome of breast cancer patients treated outside of clinical trials. J Cancer. 2014;5:491–498. doi: 10.7150/jca.9216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mukherji D, Abed El Massih S, Daher M, et al: Prostate cancer stage at diagnosis: First data from a Middle-Eastern cohort. J Clin Oncol 35, 2017 (suppl; abstr e552) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lautier M. Export of health services from developing countries: The case of Tunisia. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kangas B. Traveling for medical care in a global world. Med Anthropol. 2010;29:344–362. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2010.501315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zafar SY, Newcomer LN, McCarthy J, et al. How should we intervene on the financial toxicity of cancer care? One shot, four perspectives. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:35–39. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_174893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witte J, Mehlis K, Surmann B, et al. Methods for measuring financial toxicity after cancer diagnosis and treatment: A systematic review and its implications. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1061–1070. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120:3245–3253. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure: Out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1484–1486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1306826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connell J. A new inequality? Privatisation, urban bias, migration and medical tourism. Asia Pac Viewp. 2011;52:260–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8373.2011.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inhorn MC, Patrizio P. Rethinking reproductive “tourism” as reproductive “exile”. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:904–906. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]