Abstract

Background: Palliative care can alleviate symptom burden, reduce psychosocial distress, and improve quality of life for patients suffering from serious or life-threatening illnesses. However, the extent to which U.S. adults are aware of or understand the goals and benefits of palliative care is not well understood. Public awareness of palliative care is necessary to change norms and create demand, and as such, limited awareness may be a significant barrier to palliative care uptake. An assessment of current palliative care awareness in the United States is needed to inform the health care sector's improving palliative care communication and delivery.

Objective: To examine the prevalence of palliative care awareness among a nationally-representative sample of U.S. adults and to identify sociodemographic and health-related characteristics associated with palliative care awareness.

Design: Weighted data from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS 5, Cycle 2 [2018], N = 3445) were used to produce frequencies of the characteristics, and associations with palliative care awareness were determined through multiple logistic regression.

Results: An estimated 71% of U.S. adults reported having never heard of palliative care. Older individuals, those with higher educational attainment, women, and whites (vs. nonwhites) had greater odds of palliative care awareness.

Conclusions: These data suggest there is limited awareness of palliative care in the United States, despite its documented benefits. Addressing this awareness gap is a priority to change norms around using palliative care services. Community- and population-based interventions are necessary to raise awareness and inform the public about palliative care.

Keywords: end of life, palliative care, quality of life

Introduction

The American Medical Association defines palliative care as “that which relieves suffering and improves quality of life for people with serious illnesses, no matter whether they can be cured.1” Although palliative care has many demonstrated benefits, including improving patients' quality of life and addressing symptom burden, gaps in access to and uptake of palliative care persist.2 This low uptake has been attributed to inconsistent understanding about the role of palliative care3 and limited patient–provider communication about the benefits of palliative care.4 Palliative care definitions have been ambiguous and at times conflicting, and there are misperceptions about palliative care among providers,5,6 patients, and caregivers. A 2011 study also found relatively low awareness of palliative care among the general public.6

Educating the public and newly diagnosed patients about palliative care has been found to decrease fear and increase intention to use palliative care services; it can potentially normalize and increase demand for palliative care services.7 To inform the development of patient education, clinical support, and community-based interventions aimed at facilitating communication about palliative care, it is important to first assess the current level of palliative care awareness in the United States. Furthermore, to develop effective patient-centered interventions that meet the needs of diverse patient populations, it is necessary to identify demographic and health care-related factors associated with palliative care awareness. Knowing which demographic groups are least likely to have palliative care awareness may inform prioritization and allocation of resources for targeted communication efforts to improve palliative care awareness before a need for such services arises.8 Using a nationally representative sample, this study aims to report the current (2018) level of self-reported awareness of palliative care among U.S. adults, and to identify sociodemographic and health care-related predictors of palliative care awareness.

Methods

The most recent iteration of the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS 5, Cycle 2), administered by the National Cancer Institute, was used to provide nationally-representative estimates of U.S. adults' palliative care awareness. Data were collected during January–May 2018 using residential sampling. Methodology reports on the framework and design are published elsewhere,9 and data (as well as more detailed information about the methodology and measures) can be found online at hints.cancer.gov.

The outcome variable, palliative care awareness, was assessed by a single item: “How would you describe your level of knowledge about palliative care?” Responses were dichotomized as aware of palliative care (I know a little bit about palliative care or I know what palliative care is and could explain it to someone else) and not aware of palliative care (Never heard of palliative care). Standard sociodemographic variables were included as predictors of palliative care awareness: age, gender (male/female), race/ethnicity (dummy-coded; e.g., white or nonwhite), education (high school or less, post-high school/some college, college graduate, or postgraduate), and geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West). Personal cancer experience (ever/never) and status serving as a current caregiver to someone with a serious health problem (yes/no) were included to examine whether experience with a cancer diagnosis or engagement with the health care system predicted palliative care awareness.

Descriptive statistics were produced to determine the prevalence of palliative care awareness; bivariate and multivariable logistic regression models were used to determine significant predictors of palliative care awareness using SAS 9.4. To account for the complex sampling design and generate nationally-representative estimates, jackknife replicate weights were applied to all analyses.

Results

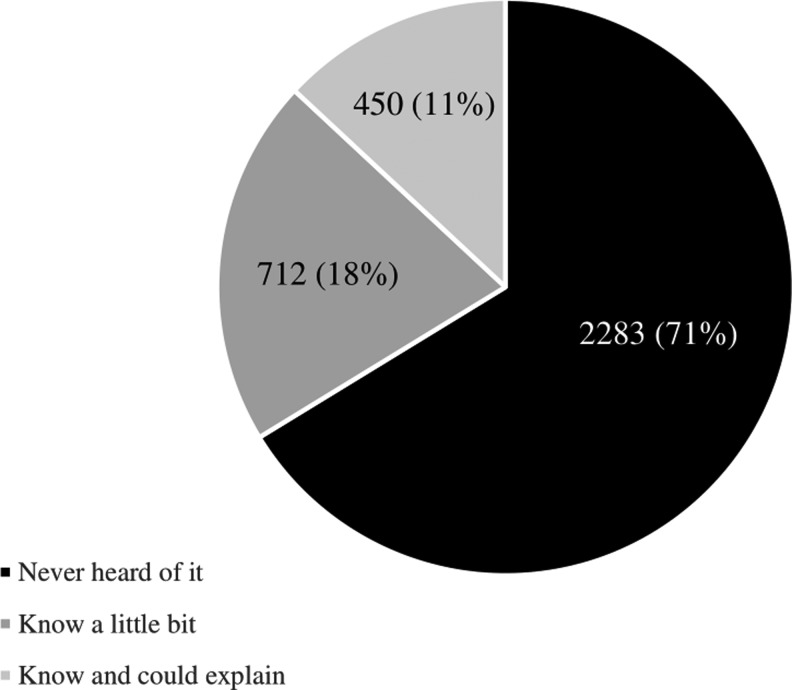

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the weighted sample, as well as descriptive statistics stratified by level of palliative care awareness. Figure 1 suggests that nearly three-quarters (71%; n = 2283) of U.S. adults have never heard of palliative care, whereas 18% (n = 712) knew a little about it, and 11% (n = 450) could explain palliative care to someone else; the latter two were combined in the subsequent analysis.

Table 1.

Frequencies and Weighted Percentages of Participants' Sociodemographic Characteristics, by PC Awareness

| Characteristic | Full sample | Never heard of PC (n = 2283, 71%) | Know a little bit about PC (n = 712, 18%) | Know and could explain PC (n = 450, 11%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 | 413 (24) | 297 (27.1) | 68 (17.6) | 48 (14.7) |

| 35–49 | 626 (25.9) | 407 (25.7) | 123 (22.5) | 96 (32.4) |

| 50–64 | 1123 (30.3) | 714 (28.7) | 252 (35) | 157 (33.1) |

| 65+ | 1243 (19.8) | 839 (18.5) | 260 (25) | 144 (19.9) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1400 (49) | 1051 (54.1) | 232 (39) | 117 (30.8) |

| Female | 2045 (51) | 1232 (45.9) | 480 (61) | 333 (69.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 2487 (79.9) | 1544 (77.9) | 582 (85.6) | 361 (83.4) |

| Nonwhite | 744 (20.1) | 559 (22.1) | 115 (14.4) | 70 (16.6) |

| Black | 586 (14.6) | 441 (15.9) | 83 (10) | 62 (13.6) |

| Nonblack | 2645 (85.4) | 1662 (84.1) | 614 (90) | 369 (86.4) |

| Hispanic | 490 (15.5) | 381 (18.2) | 66 (8.5) | 43 (9.6) |

| Non-Hispanic | 2955 (84.5) | 1902 (81.8) | 646 (91.5) | 407 (90.4) |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 900 (31.1) | 761 (38) | 104 (17.5) | 35 (7.7) |

| Post-HS and some college | 1032 (39.9) | 718 (40) | 196 (40) | 118 (39.5) |

| College graduate | 915 (17.7) | 562 (15.7) | 209 (21.1) | 144 (25.5) |

| Postgraduate | 598 (11.3) | 242 (6.3) | 203 (21.4) | 153 (27.3) |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 517 (17.7) | 319 (16.5) | 122 (20.4) | 76 21.3) |

| Midwest | 626 (21) | 422 (21.7) | 135 (20.8) | 69 (16.8) |

| South | 1490 (37.6) | 994 (37.1) | 299 (38.4) | 197 (39.2) |

| West | 812 (23.7) | 548 (24.7) | 156 (20.4) | 108 (22.6) |

| Past cancer diagnosis | ||||

| No, never diagnosed with cancer | 2857 (90.6) | 1902 (91.3) | 600 (90.7) | 355 (85.6) |

| Yes, have been diagnosed with cancer | 588 (9.4) | 381 (8.7) | 112 (9.3) | 95 (14.4) |

| Current caregiver experience | ||||

| No, currently not a caregiver | 2876 (85) | 1952 (87.6) | 582 (81.2) | 342 (73.8) |

| Yes, currently a caregiver | 472 (15) | 262 (12.4) | 115 (18.8) | 95 (26.2) |

Health Information National Trends Survey, 2018 (n = 3445).

HS, high school.

FIG. 1.

Prevalence of awareness about palliative care. Awareness of palliative care is defined in response to the item: “How would you describe your level of knowledge about palliative care?”

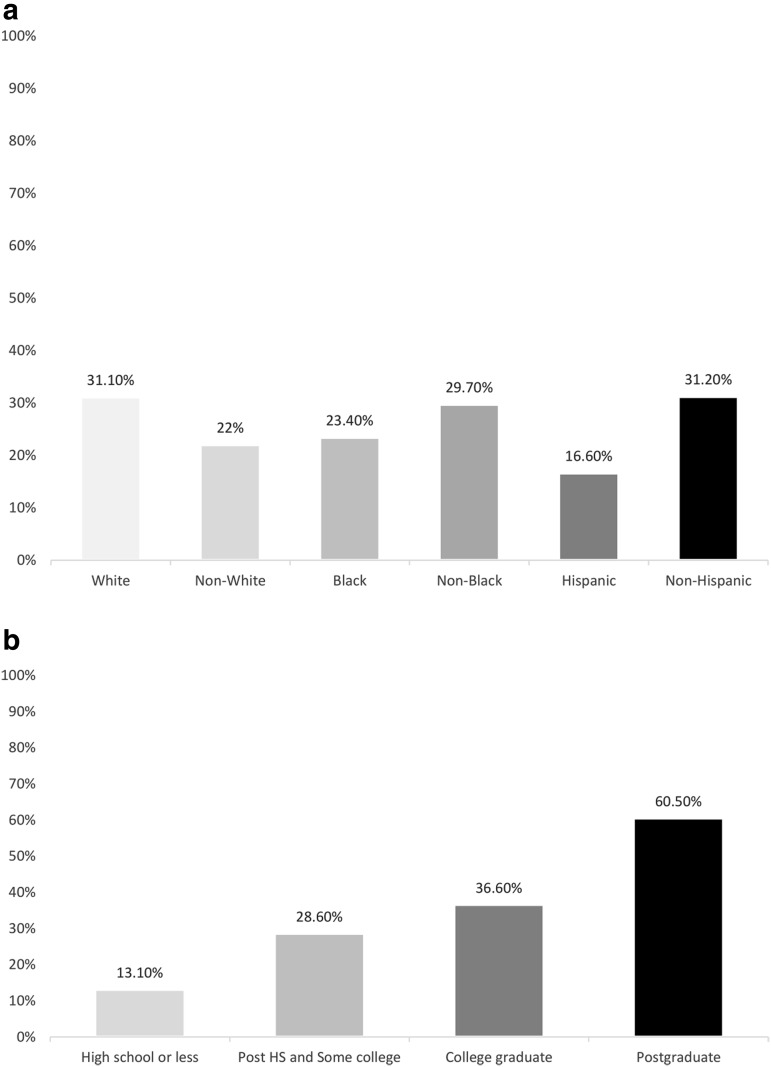

The multivariable logistic regression model identified a number of significant sociodemographic predictors of awareness (Table 2). Women (odds ratio [OR] = 2.41, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.84–3.17) and those reporting white race (vs. nonwhite; OR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.23–2.75) had greater odds of being aware of palliative care. Those reporting Hispanic ethnicity (vs. non-Hispanic; OR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.36–0.98) had lower odds of being aware of palliative care. In addition, compared with those aged 18–34 years, individuals aged 35–49 (OR = 1.79, 95% CI = 1.10–2.90), 50–64 (OR = 2.44, 95% CI = 1.57–3.81) and 65+ (OR = 2.62, 95% CI = 1.72–3.97) reported greater odds of being aware of palliative care. In addition, compared with individuals with a high school education or less, those who completed high school or some college (OR = 2.73, 95% CI = 1.83–4.06), college graduates (OR = 4.37, 95% CI = 2.80–6.81), and postgraduates (OR = 11.08, 95% CI = 6.95–17.68) were more likely to be aware of palliative care. Adjusted predicted rates of palliative care awareness by race/ethnicity and education are described in Figure 2a and b. Past cancer diagnosis and currently being a caregiver were not significantly associated with palliative care awareness.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Multivariable Logistic Regression of Characteristics Predicting Awareness About Palliative Carea

| Demographic/health characteristic | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–34 | REF | REF | ||||||

| 35–49 | 1.78 | 1.14 | 2.77 | 0.01 | 1.79 | 1.10 | 2.90 | 0.02 |

| 50–64 | 2.06 | 1.36 | 3.11 | <0.001 | 2.44 | 1.57 | 3.81 | <0.001 |

| 65+ | 2.21 | 1.52 | 3.21 | <0.001 | 2.62 | 1.721 | 3.97 | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | REF | REF | ||||||

| Female | 2.39 | 1.86 | 3.07 | <0.001 | 2.41 | 1.84 | 3.17 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||||||

| White vs. nonwhite | 1.52 | 1.05 | 2.21 | 0.03 | 1.84 | 1.23 | 2.75 | <0.001 |

| Black vs. nonblack | 0.68 | 0.55 | 1.05 | 0.08 | 1.32 | 0.80 | 2.19 | 0.28 |

| Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.77 | 0.003 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.04 |

| Education | ||||||||

| High school or less | REF | REF | ||||||

| Post-HS and some college | 2.58 | 1.79 | 3.71 | <0.001 | 2.73 | 1.83 | 4.06 | <0.001 |

| College graduate | 3.93 | 2.67 | 5.79 | <0.001 | 4.37 | 2.80 | 6.81 | <0.001 |

| Postgraduate | 9.98 | 6.61 | 15.07 | <0.001 | 11.08 | 6.95 | 17.67 | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||||||

| Northeast | REF | REF | ||||||

| Midwest | 0.59 | 0.41 | 0.86 | 0.01 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 1.19 | 0.26 |

| South | 0.78 | 0.56 | 1.08 | 0.13 | 0.89 | 0.60 | 1.32 | 0.57 |

| West | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 0.83 | 0.54 | 1.27 | 0.38 |

| Past cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| No, never diagnosed with cancer | REF | REF | ||||||

| Yes, been diagnosed with cancer | 1.33 | 1.00 | 1.76 | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.72 | 1.36 | 0.95 |

| Current caregiver experience | ||||||||

| No, currently not a caregiver | REF | REF | ||||||

| Yes, currently a caregiver | 1.88 | 1.33 | 2.65 | <0.001 | 1.45 | 0.98 | 2.15 | 0.06 |

Hot-deck imputation was used to replace missing responses with imputed data for age, gender, educational attainment, ethnicity, and past cancer diagnosis. The adjusted multivariable model fully adjusts for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, region, past cancer diagnosis, and current caregiver experience.

Each race/ethnicity variable was entered as a dummy-coded variable (e.g., white vs. nonwhite). Unadjusted results are reported from the bivariate model and adjusted results are reported from the multivariable model.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Bold values are reported in the results section.

FIG. 2.

(a) Adjusted rate of individuals who know at least a little about palliative care, by race/ethnicity. (b) Adjusted rate of individuals who know at least a little about palliative care, by education.

Discussion

This nationally-representative survey analysis revealed that more than two-thirds of U.S. adults reported having never heard of palliative care. This finding raises concerns for practitioners and policy makers. The limited awareness in the general public stands in stark contrast to movements to increase early integration of palliative care as a standard of care regardless of curative intent.10 It is an important reminder for clinicians not to assume that patients and caregivers know about palliative care or its benefits. Moreover, ongoing efforts to improve palliative care communication and decision support may be hindered by low baseline awareness.11 Specifically, low awareness of palliative care could explain why many in the United States do not inquire about palliative care despite suffering from serious illnesses. Limited awareness may also make them more likely to have misperceptions about palliative care, consequently requiring extra efforts to communicate with them about palliative care when a need arises. Research suggests that when patients are informed and educated about palliative care, they largely choose to receive it.12 Therefore, raising public awareness may facilitate interest in and decisions to use palliative care services at a time of need. Finally, awareness about palliative care can help normalize palliative care and reduce associated stigma, improve patient self-efficacy, and increase overall demand. Raising awareness of palliative care is necessary but not sufficient; disseminating accurate knowledge about palliative care is also critically important. Self-reported awareness of palliative care does not necessarily translate into accurate knowledge of palliative care. This study did not examine the accuracy of the knowledge held by the 18% of respondents who reported knowing a little bit and the 11% who reported being able to explain palliative care to someone else. Future research is needed to assess the level of accurate palliative care knowledge.

The analysis of factors associated with palliative care awareness suggests that age, gender, race/ethnicity, and education are robust predictors of palliative care awareness. Older individuals are more likely to be aware of palliative care, possibly given more life course experience with chronic illnesses.13 However, fine-grained age differences may be masked in this analysis, which treated age categorically, warranting further in-depth analyses. Higher awareness among women might reflect women's tendencies to seek more information about treatment options.14 These demographic differences point to a need for targeted palliative care communication and education efforts directed to younger individuals and men. Our findings provide some insight into known disparities in palliative care uptake. For example, research suggests that racial minorities underuse palliative care even with sufficient access; this might be due to communication barriers, lack of trust in the health care system, and lack of insurance coverage or limited reimbursement.15 In addition, investigation of narrower regional differences may be needed to assess whether geographical areas where individuals of racial/ethnic minorities and low socioeconomic status are underserved by palliative care. Future work is needed to nest these individual factors within the broader set of structural barriers that exist, particularly access to palliative care services. This is particularly important to the extent that these structural barriers may covary with individual factors, such as race. Moreover, lower palliative care awareness among those with limited educational attainment suggests the need for more systematic efforts targeting individuals with lower education within health care and community settings (e.g., through tailored decision aids). Lastly, it is notable that being diagnosed with cancer or currently serving as a caregiver did not predict palliative care awareness in the multivariable model.

This analysis is one of the first to examine a nationally-representative sample of U.S. adults' awareness of palliative care. In addition, it examines the factors associated with level of palliative care awareness, which may inform future work aimed at increasing palliative use among diverse populations. Limitations to this study include lack of availability of broader indices of illness experience and an inability to examine reasons for the nonsignificant association between cancer history, caregiver experience, and palliative care awareness. Possible explanations include small cell sizes or palliative care awareness being context sensitive. Concerted efforts to promote awareness and understanding of palliative care among the general public may help support informed decision making; such endeavors should begin with the populations with the least awareness and most needs.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. American Medical Association: Hospice and Palliative Care. [Issue Brief] 2017. [cited 2018]. www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/public/about-ama/councils/Council%20Reports/council-on-medical-service/issue-brief-hospice-palliative-care.pdf (last accessed November1, 2018)

- 2. Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. : Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;316:2104–2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmedzai SH, Costa A, Blengini C, et al. : A new international framework for palliative care. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:2192–2200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hsiao JL, Evan EE, Zeltzer LK: Parent and child perspectives on physician communication in pediatric palliative care. Palliat Supportive Care 2007;5:355–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pastrana T, Jünger S, Ostgathe C, Elsner F, Radbruch L: A matter of definition–key elements identified in a discourse analysis of definitions of palliative care. Palliat Med 2008;22:222–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Care CTAP: 2011 Public Opinion Research on Palliative Care: A Report Based on Research by Public Opinion Strategies. New York: Center to Advance Palliative Care, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoerger M, Perry LM, Gramling R, Epstein RM, Duberstein PR: Does educating patients about the Early Palliative Care Study increase preferences for outpatient palliative cancer care? Findings from Project EMPOWER. Health Psychol 2017;36:538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pillemer K, Chen EK, Riffin C, Prigerson H, Reid MC: Practice-based research priorities for palliative care: Results from a research-to-practice consensus workshop. Am J Public Health 2015;105:2237–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nelson D, Kreps GL, Hesse BW, et al. : The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS): Development, design, and dissemination. J Health Commun 2004;9:443–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Smith TJ: Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update Summary. J Oncol Pract 2017;13:119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lovell A, Yates P: Advance care planning in palliative care: A systematic literature review of the contextual factors influencing its uptake 2008–2012. Palliat Med 2014;28:1026–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wiener L, Weaver MS, Bell CJ, Sansom-Daly UM: Threading the cloak: Palliative care education for care providers of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Clin Oncol Adolesc Young Adults 2015;5:1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morrison RS: Research priorities in geriatric palliative care: An introduction to a new series. J Palliat Med 2013;16:726–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koffman J, Burke G, Dias A, et al. : Demographic factors and awareness of palliative care and related services. Palliat Med 2007;21:145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crawley L, Payne R, Bolden J, et al. : Palliative and end-of-life care in the African American community. JAMA 2000;284:2518–2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]