Abstract

Aims.

Mental health policy internationally varies in its support for recovery. The aims of this study were to validate an existing conceptual framework and then characterise by country the distribution, scientific foundations and emphasis in published recovery conceptualisations.

Methods.

Update and modification of a previously published systematic review and narrative synthesis of recovery conceptualisations published in English.

Results.

A total of 7431 studies were identified and 429 full papers reviewed, from which 105 conceptualisations in 115 papers were included and quality assessed using established rating scales. Recovery conceptualisations were identified from 11 individual countries, with 95 (91%) published in English-speaking countries, primarily the USA (47%) and the UK (25%). The scientific foundation was primarily qualitative research (53%), non-systematic literature reviews (24%) and position papers (12%). The conceptual framework was validated with the 18 new papers. Across the different countries, there was a relatively similar distribution of codings for each of five key recovery processes.

Conclusions.

Recovery as currently conceptualised in English-language publications is primarily based on qualitative studies and position papers from English-speaking countries. The conceptual framework was valid, but the development of recovery conceptualisations using a broader range of research designs within other cultures and non-majority populations is a research priority.

Key words: Recovery, systematic review, conceptual framework

Introduction

The term ‘recovery’ has become prominent in mental health systems internationally. Yet across different countries and settings, the term is used inconsistently and with differing implications for policy and practice. It has been suggested that this reflects an important debate about the core purpose of mental health services (Slade, 2009c). This debate has been characterised in two ways: as a difference in emphasis and as a paradigmatic tension.

What is ‘recovery’?

Proponents of the first characterisation emphasise the continuity between current conceptualisations about recovery and past initiatives in psychiatry. For example, in Europe, these would include Querido's development of social psychiatry in the Netherlands, the York Retreat in England, Pinel's asylum in France and the Basgalia Law in Italy. Social activists with no connection to the mental health system have also been included in the lineage of recovery thinking (Davidson et al. 2010a). This characterisation emphasises that different meanings of recovery exist, which are compatible and reflect differing needs at different points in an individual's journey. In England, this has involved the recommendation that ‘alongside a traditional emphasis on understanding psychopathology and treatment, the application of recovery values…would suggest: progressively involving experts by experience as trainers…; the importance of intentional peer support (Mead, 2005); the significance of narrative perspectives; self-management and self-directed care; and how mental health staff, people who use services and carers can work collaboratively to optimise recovery possibilities’ (Care Services Improvement Partnership, 2007) (p. 25).

The second way this debate has been characterised is as tension between opposing paradigms. These have been variously labelled as recovery ‘from’ v. recovery ‘in’ (Davidson et al. 2008b); clinical recovery v. social recovery (Secker et al. 2002); scientific v. consumer models of recovery (Bellack, 2006); and service-based recovery v. user-based recovery (Schrank & Slade, 2007).

An emergent differentiation is between clinical recovery and personal recovery (Slade, 2009b). Clinical recovery has emerged from professional-led research and practice, and involves returning to normal. For example, a widely used definition is that recovery comprises full symptom remission, full- or part-time work or education, independent living without supervision by informal carers, and having friends with whom activities can be shared, all sustained for a period of 2 years (Libermann & Kopelowicz, 2002). One merit of this definition of recovery is that epidemiological evidence on recovery rates can be collected (Arvidsson, 2011), showing for example that the majority (i.e. >50%) of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia will over a 20-year period experience clinical recovery (Slade et al. 2008). An orientation towards clinical recovery leads to a focus on ensuring access to effective treatments (Semisa et al. 2008).

However, people who use mental health services have challenged the assumptions about normality embedded in clinical recovery: ‘this kind of definition begs several questions that need to be addressed to come up with an understanding of recovery as an outcome: How many goals must be achieved to be considered recovered? For that matter, how much life success is considered ‘normal’?’ (Ralph, 2005, p. 5). People personally affected by mental illness have increasingly communicated both what their life is like with the mental illness and what helps in moving beyond the role of a patient (Romme et al. 2009). The understanding of recovery which has emerged from these narrative accounts differs in its focus from clinical recovery. A widely cited definition was put forward by William Anthony in 1993: ‘Recovery is a deeply personal, unique process of changing one's attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills, and/or roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even within the limitations caused by illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one's life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness’ (Anthony, 1993, p. 17). A briefer definition – in contrast to the clinical recovery focus on getting back to normal – is that recovery involves ‘living as well as possible’ (South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, 2010, p. 6).

Is recovery an international phenomenon?

A policy orientation towards personal recovery – generally defined using the Anthony definition in the previous paragraph – is present in some countries and absent in others (Slade et al. 2008). Broadly, a recovery approach is enshrined in the policy of most English-speaking countries, somewhat present in German-speaking Europe and not present in Central and Northern Europe, Asia and Africa. This is reflected in a recent review of recovery developments internationally, which features papers from Australia, Austria, Canada, England, Hong Kong, Israel, New Zealand, Scotland and the USA (Slade et al. in press).

This uneven policy endorsement may be due to a range of reasons. These include the absence of any mental health-specific policy in some countries; an opposition to a recovery orientation in principle; and an absence of recovery research relevant to the specific country. This study was undertaken to provide an evidence base to understand better the global distribution of pro-recovery policy, by systematically reviewing conceptualisations of recovery and analysing these in relation to their country of origin. The aims were to validate an existing coding framework for recovery processes, and then to use this coding framework to characterise by country the distribution, scientific foundations and emphasis in recovery conceptualisations.

Method

This systematic review updated and modified a previously published systematic review and narrative synthesis of the literature on the meaning of personal recovery (Leamy et al. 2011). The original review collated evidence available until September 2009, and did not report findings by country. Data and the coding framework from the original review are used in this review. Additionally, the original review was updated by including studies published from September 2009 to August 2011, and the synthesis was modified by analysing studies by country of origin.

Eligibility criteria

The review sought to identify papers that explicitly described or developed a conceptualisation of personal recovery from mental illness. A conceptualisation of recovery was defined as either a visual or narrative model of recovery, or themes of recovery, which emerged from a synthesis of secondary data or an analysis of primary data. Inclusion criteria for studies were: (i) contains a conceptualisation of personal recovery from which a succinct summary could be extracted; (ii) presented an original model or framework of recovery; (iii) based on either secondary research synthesising the available literature or primary research involving quantitative or qualitative data based on at least three participants; (iv) available in printed or downloadable form; and (v) available in English. Exclusion criteria were: (a) studies solely focusing on clinical recovery (i.e. using a predefined and invariant ‘getting back to normal’ definition of recovery through symptom remission and restoration of functioning); (b) studies involving modelling of predictors of clinical recovery; (c) studies defining remission criteria or recovery from substance misuse, addiction or eating disorders; and (d) dissertations and doctoral theses (due to article availability).

Search strategy and data sources

Three search strategies were used to identify relevant studies: electronic database searching (original search and updated search), hand searching (original search only) and web-based searching (original search only).

-

(1)

Twelve bibliographic databases were initially searched using three different interfaces: AMED; British Nursing index; EMBASE; MEDLINE; PsycINFO; Social Science Policy (accessed via OVID SP); CINAHL; International Bibliography of Social Science (accessed via EBSCOhost and ASSIA); British Humanities Index; Sociological abstracts; and Social Services abstracts (accessed via CSA Illumina). All databases were searched from inception to August 2011 using the following terms identified from the title, abstract, key words or medical subject headings: (‘mental health’ OR ‘mental illness$’ OR ‘mental disorder’ OR mental disease' OR ‘mental problem’) AND ‘recover$’ AND (‘theor$’, OR ‘framework’, OR ‘model’, OR ‘dimension’, OR ‘paradigm’ OR ‘concept$’). The search was adapted for the individual databases and interfaces as needed. For example, CSA Illumina only allows the combination of three ‘units’ each made up of three search terms at any one time e.g. (‘mental health’ OR ‘mental illness*’ OR ‘mental disorder’) AND ‘recover*’ AND (‘theor$’ OR ‘framework’ OR ‘concept’). As a sensitivity check, ten papers were identified by the research team as highly influential, based on number of times cited and credibility of the authors. These papers were assessed for additional terms, subject headings and key words, with the aim of identifying relevant papers not retrieved using the original search strategy. This led to the use of the following additional search terms: (‘psychol$ health’ OR ‘psychol$ illness$’ OR ‘psychol$ disorder’ OR psychol$ problem' OR ‘psychiatr$ health’, OR psychiatr$ illness$' OR ‘psychiatr$ disorder’ OR ‘psychiatr$ problem’) AND ‘recover$’ AND (‘theme$’ OR ‘stages’ OR ‘processes’). Duplicate articles identified in the original search were removed using Reference Manager Software Version 11 and identified in the updated search using Endnote X4.

-

(2)

The table of contents of journals which published key articles (Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, British Journal of Psychiatry and American Journal of Psychiatry) and literature reviews of recovery (Ralph, 2000; Care Services Improvement Partnership, 2007; Onken et al. 2007) were hand-searched.

-

(3)

Web-based resources were identified by internet searches using Google and Google Scholar and through searching specific recovery-orientated websites (Scottish Recovery Network: http://www.scottishrecovery.net; Boston University Repository of Recovery Resources: http://www.bu.edu/cpr/repository/index.html; Recovery Devon: http://www.recoverydevon.co.uk; and Social Perspectives Network: http://www.spn.org.uk).

Data extraction and quality assessment

In the original search, one rater (V.B.) extracted data and assessed the eligibility criteria for all retrieved papers, with a random sub-sample of 88 papers independently rated by a second rater (J.W. or C.L.). Disagreements between raters were resolved by a third rater (M.L.). In the updated search, two raters (F.B. and M.J.) extracted data and assessed eligibility criteria, with disagreements resolved by a third rater (V.B.). Acceptable concordance was predefined as agreement on at least 90% of ratings, and concordances of 91% in the original search and 92% in the updated search were achieved. For each included paper, the following data were extracted and tabulated: type of paper, methodological approach, participant information and inclusion criteria, study location, and summary of main study findings.

Qualitative papers were quality assessed using the RATS qualitative research review guidelines (Clark, 2003). The RATS scale comprises 25 questions about the relevance of the study question, appropriateness of qualitative method, transparency of procedures and soundness of interpretive approach. To make judgements about quality of papers, we dichotomised each question to yes (1 point) or no (0 points), giving a scale ranging from 0 (poor quality) to 25 (high quality). In the original search, papers were quality assessed by three raters (V.B., J.W. and C.L.), with a random sub-sample of 10 studies independently rated by a second rater (M.L.). The mean score from rating 1 was 14.8 and from rating 2 was 15.1, with a mean difference in ratings of 0.3 indicating acceptable concordance. In the updated search, all qualitative papers were quality assessed independently by two raters (F.B. and M.J.), achieving a rating concordance of 93.2%, with disagreements between raters resolved by a third rater (M.L.). Quantitative studies were quality assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project quality assessment tool (EPHPP, 1998), with independent identical ratings made by two reviewers (V.B. and M.L.). Systematic review papers were quality assessed using the NICE guidelines manual (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009).

Analysis

In the original review, a conceptual framework was developed from data collected during the original search, using a modified narrative synthesis approach (Popay et al. 2006). The first stage of the narrative synthesis comprised development of a preliminary synthesis using tabulation, translating data through thematic analysis of good quality primary data and vote counting of emergent themes. An initial coding framework was developed and used to thematically analyse a sub-sample of qualitative research studies with the highest RATS quality rating (i.e. RATS score of 15 or above), using NVIVO QSR International qualitative analysis software (Version 8). The main over-arching themes and related sub-themes occurring across the tabulated data were identified, using inductive, open-coding techniques. Additional codes were created by all analysts where needed and these new codes were regularly merged with the NVIVO master copy and then this copy was shared with other analysts, so all new codes were applied to the entire sub-sample. Once the themes had been created, vote counting was used to identify the frequency with which themes appeared in the 97 papers. The vote count for each category comprised the number of papers mentioning either the category itself or a subordinate category. On completion of the thematic analysis and vote counting, the draft conceptual framework was discussed and refined by all authors. Some new categories were created, and others were subsumed within existing categories, given less prominence or deleted. This process produced the preliminary conceptual framework.

In the second stage of the narrative synthesis, the relationships within and between studies were explored, with a specific focus on data involving people from Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) backgrounds. In the final stage, the robustness of the synthesis was assessed, using two approaches. First, qualitative studies that were rated as moderate quality on the RATS scale (i.e. RATS score of 14 or less) were thematically analysed until category saturation was achieved. The resulting themes were then compared with the preliminary conceptual framework developed in Stages 1 and 2. Second, the preliminary conceptual framework was sent to an expert consultation panel comprising 54 experts who had either academic, clinical or personal expertise about recovery. They were asked to comment on the positioning of concepts within different hierarchical levels of the conceptual framework, identify any important areas of recovery which they felt had been omitted and make any general observations. The preliminary conceptual framework was modified in response to these comments, to produce the final conceptual framework used in the current study.

Data from papers identified in the updated search were deductively coded using the first- and second-order themes (shown in Table 2) as the coding framework. Once the themes were coded, vote counting was carried out to calculate the frequency of each of the themes. The aim of the vote counting process was to quantify the number of papers in which the themes occurred. This meant that for each paper, a category, if present, was only counted once, regardless of the number of times it appeared in the text. One rater (M.L.) conducted the vote counting for all papers identified in the updated search. To improve the reliability, double vote counting was carried out by another researcher (F.B., M.J., C.L. or J.W.), with disagreements between researchers resolved by discussion. A concordance of 82% was achieved. All papers from both the original and updated search were then grouped by the country in which the studies had taken place, based on the study description and (when not stated) the author affiliations. The frequency of each theme per country was then calculated.

Table 2.

Validation of the deductive-coding framework

| Original search | Updated search | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of conceptualisations | 87 | 18 | 105 |

| RECOVERY PROCESS | |||

| Connectedness number (%) coded | 75 (86) | 17 (94) | 92 (87) |

| Peer support and support groups | 39 (45) | 13 (72) | 52 (50) |

| Relationships | 33 (38) | 13 (72) | 46 (44) |

| Support from others | 53 (61) | 13 (72) | 66 (63) |

| Being part of the community | 35 (40) | 3 (17) | 38 (36) |

| Hope and optimism about the future | 69 (79) | 16 (89) | 85 (81) |

| Motivation to change | 15 (17) | 14 (78) | 29 (28) |

| Belief in possibility of recovery | 30 (34) | 12 (67) | 42 (40) |

| Positive thinking and valuing success | 10 (11) | 5 (28) | 15 (14) |

| Having dreams and aspirations | 7 (8) | 11 (61) | 18 (17) |

| Hope-inspiring relationships | 12 (14) | 3 (17) | 15 (14) |

| Identity | 65 (75) | 17 (94) | 82 (78) |

| Dimensions of identity | 8 (9) | 3 (17) | 11 (10) |

| Rebuilding/redefining positive identity | 57 (66) | 15 (83) | 72 (69) |

| Over-coming stigma | 40 (46) | 17 (94) | 57 (54) |

| Meaning in life | 72 (83) | 18 (100) | 90 (86) |

| Meaning of mental illness experiences | 30 (34) | 16 (89) | 46 (44) |

| Spirituality | 32 (37) | 8 (44) | 44 (42) |

| Quality of life | 57 (66) | 17 (94) | 74 (70) |

| Meaningful life and social roles | 40 (46) | 3 (17) | 43 (41) |

| Meaningful life and social goals | 15 (17) | 15 (83) | 30 (29) |

| Rebuilding of life | 19 (22) | 13 (72) | 32 (30) |

| Empowerment | 77 (89) | 17 (94) | 96 (91) |

| Personal responsibility | 77 (89) | 17 (94) | 96 (91) |

| Control over life | 77 (89) | 17 (94) | 95 (90) |

| Focusing upon strengths | 14 (16) | 5 (28) | 19 (18) |

Results

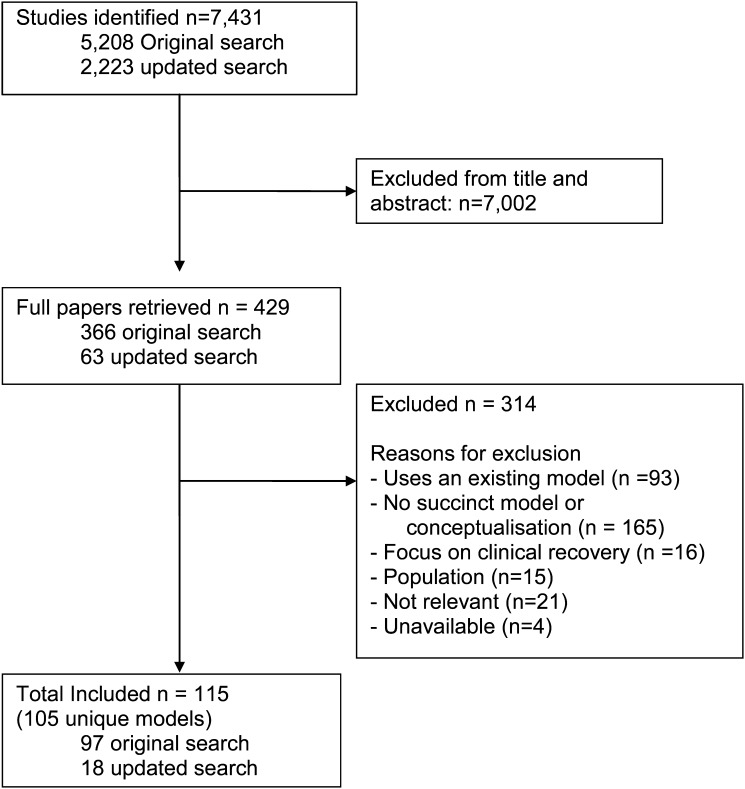

A total of 115 papers describing 105 conceptualisations of recovery were identified. The flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for identification of recovery models.

The 97 studies (reporting 87 new conceptualisations of recovery) in the original search were listed in the general paper (Leamy et al. 2011). In the updated search, 18 new studies were identified (Vogel-Scibilia et al. 2009; Romme et al. 2009; Dilks et al. 2010; Kartalova-O'Doherty & Tedstone Doherty, 2010; Kelly et al. 2010; Mansell et al. 2010; Mezey et al. 2010; Noiseux et al. 2010; Romano et al. 2010; Schön, 2010; Wood et al. 2010; Davidson et al. 2010b; Green et al. 2011; Holm & Severinsson, 2011; Kogstad et al. 2011; Turton et al. 2011; Stickley & Wright, 2011a, 2011b).

The scientific foundations for the 105 conceptualisations of recovery are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scientific foundation of identified models (n = 105)

| USA | UK | Canada | Australia | Ireland | Norway | Sweden | New Zealand | Taiwan | South Korea | Iceland | Mixed | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 49 | 26 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 105 |

| Design | |||||||||||||

| Systematic review | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Narrative review | 14 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 25 | ||||||

| Quantitative | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Qualitative | 24 | 12 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 55 | |

| Mean RATS score | 14 | 17 | 18 | 12 | 18 | 15 | 14 | 20 | 15 | 16 | 14 | ||

| Consensus methods | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Position paper | 6 | 4 | 3 | 13 | |||||||||

| Book chapter | 3 | 4 | 7 |

The quantitative study was rated as moderate quality, and the two systematic reviews were rated as 3/5 and 4/5.

Conceptualisations of recovery were identified from 11 individual countries, plus two mixed-country studies: UK and Austria (Schrank & Slade, 2007), and UK and Australia (Ramon et al. 2007). Four countries each had one identified paper: New Zealand (Lapsley et al. 2002), Taiwan (Song & Shih, 2009), South Korea (Sung et al. 2006) and Iceland (Asmundsdottir, 2009).

The final conceptual framework comprised three inter-linked, super-ordinate categories: Characteristics of the Recovery Journey; Recovery Processes; and Recovery Stages. The Recovery Processes comprised connectedness, hope and optimism about the future, identity, meaning in life and empowerment (summarised using the acronym CHIME), and are the focus of the current study since they have the most proximal relevance to clinical research and practice.

Within the CHIME framework, connectedness related not only to the connections, relationships and social support individuals have with other people, but also included connections to the wider community and to society as a whole. Different types of support were therefore incorporated within the connectedness category, including peer support, support from professionals and support from the community, family and friends. Hope was defined as vital to the process of recovery: people needed to have hope and a belief in their own recovery, but also needed others to believe in them. Hope also included the belief that things would get better, which often provided the motivation for change. Part of the process of overcoming mental illness, involved the individual's identity. In particular, redefining and rebuilding a positive sense of identity were identified as key recovery processes. Within the framework, meaning in life was a broad category, including many themes related to finding meaning in life and also meaning associated with the mental illness experience. Sub-categories described different ways individuals could find meaning, including through social roles, goals, employment and meaningful activities. Finally, the CHIME framework included empowerment, which related both to a sense of empowerment within mental health services – such as having control over treatment and having personal responsibility – and also included becoming an empowered member of society.

The CHIME categories and sub-categories were identified in the original review. To validate this coding framework, it was applied deductively to the papers identified in the updated review. The results are compared in Table 2.

Codings in papers identified in the updated search were at least as frequent for nearly all sub-categories as codings in papers identified in the original search, providing some evidence that the coding framework remains valid in more recent studies.

Codings for all papers were then considered. Papers were grouped by country. Codings in the four papers from individual countries (Iceland, New Zealand, South Korea and Taiwan) spanned all five CHIME categories, apart from the South Korea study that coded Connectedness and Meaning in life only. The distribution of coding categories for the seven countries with more than one paper is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Conceptual framework coding for recovery conceptualisations (n = 105), organised by country

| USA | UK | Canada | Australia | Ireland | Norway | Sweden | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of conceptualisations | 49 | 26 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 105 |

| RECOVERY PROCESS | ||||||||

| Connectedness number (%) coded | 43 (88) | 22 (85) | 6 (75) | 7 (100) | 3 (75) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 92 (87) |

| Peer support and support groups | 24 (49) | 15 (58) | 3 (38) | 2 (29) | 3 (75) | 1 (33) | 2 (100) | 52 (50) |

| Relationships | 20 (41) | 14 (54) | 4 (50) | 1 (14) | 1 (25) | 1 (33) | 2 (100) | 46 (44) |

| Support from others | 29 (59) | 17 (65) | 4 (50) | 4 (57) | 3 (75) | 2 (67) | 2 (100) | 66 (63) |

| Being part of the community | 18 (37) | 11 (42) | 2 (25) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 2 (67) | 1 (50) | 38 (36) |

| Hope and optimism about the future | 38 (78) | 23 (88) | 6 (75) | 5 (71) | 4 (100) | 2 (67) | 2 (100) | 85 (81) |

| Motivation to change | 10 (20) | 8 (31) | 4 (50) | 1 (14) | 2 (50) | 2 (67) | 1 (50) | 29 (28) |

| Belief in possibility of recovery | 21 (43) | 9 (35) | 3 (38) | 2 (29) | 1 (25) | 2 (67) | 2 (100) | 42 (40) |

| Positive thinking and valuing success | 3 (6) | 5 (19) | 5 (63) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 1 (50) | 15 (14) |

| Having dreams and aspirations | 6 (12) | 6 (23) | 2 (25) | 1 (14) | 1 (25) | 1 (33) | 1 (50) | 18 (17) |

| Hope-inspiring relationships | 7 (14) | 5 (19) | 1 (13) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 15 (14) |

| Identity | 41 (83) | 21 (81) | 5 (63) | 4 (57) | 3 (75) | 2 (67) | 2 (100) | 82 (78) |

| Dimensions of identity | 2(4) | 8 (31) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (10) |

| Rebuilding/redefining positive identity | 5 (63) | 5 (63) | 5 (63) | 5 (63) | 5 (63) | 2 (67) | 2 (100) | 72 (69) |

| Over-coming stigma | 28 (57) | 15 (58) | 4 (50) | 2 (29) | 2 (50) | 3 (100) | 1 (50) | 57 (54) |

| Meaning in life | 39 (80) | 24 (92) | 7 (88) | 7 (100) | 3 (75) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 90 (86) |

| Meaning of mental illness experiences | 17 (35) | 16 (62) | 5 (63) | 1 (14) | 1 (25) | 2 (67) | 2 (100) | 46 (44) |

| Spirituality | 18 (37) | 13 (50) | 5 (63) | 2 (29) | 1 (25) | 1 (33) | 1 (50) | 44 (42) |

| Quality of life | 31 (63) | 23 (88) | 6 (75) | 3 (43) | 2 (50) | 2 (67) | 2 (100) | 74 (70) |

| Meaningful life and social roles | 21 (43) | 10 (38) | 4 (50) | 4 (57) | 1 (25) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 43 (41) |

| Meaningful life and social goals | 9 (18) | 10 (38) | 3 (38) | 2 (29) | 2 (50) | 2 (67) | 1 (50) | 30 (29) |

| Rebuilding of life | 13 (27) | 9 (35) | 3 (38) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 2 (67) | 1 (50) | 32 (30) |

| Empowerment | 44 (90) | 25 (96) | 7 (88) | 6 (86) | 4 (100) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 96 (91) |

| Personal responsibility | 44 (90) | 25 (96) | 7 (88) | 6 (86) | 4 (100) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 96 (91) |

| Control over life | 43 (88) | 25 (96) | 7 (88) | 6 (86) | 4 (100) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 95 (90) |

| Focusing upon strengths | 7 (14) | 6 (23) | 2 (25) | 6 (86) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 19 (18) |

At the top level, there was relative high frequency of coding each CHIME category, with some differences for second-level categories.

Discussion

The international literature on conceptualisations of recovery was systematically reviewed for English-language publications, and then organised by country. A substantial majority – 95 (91%) of the 105 identified conceptualisations – were published in English-speaking countries, primarily the USA (47%) and the UK (25%). The scientific foundation was primarily qualitative research (53%), non-systematic literature reviews (24%) and position papers (12%), with very few systematic reviews (2%) and quantitative empirical studies (1%). Both systematic reviews were undertaken in the UK. In relation to emphasis within each country, there was a relatively similar distribution of codings for each of the CHIME top-level categories across the different countries. There were differences in coding of second-level categories.

Dominance of western conceptualisations of recovery

This study shows that published conceptualisations of recovery in English language publications have primarily emerged from the English-speaking world. This mirrors the distribution of pro-recovery policy. Ideas about recovery are becoming visible in non-English countries, even though the translation of the term varies. In Germany, the term is used in untranslated form (Amering & Schmolke, 2007). In Hong Kong, a popular translation is 復元 (fu yuan) in which yuan (元) denotes the primordial qi (meaning energy), so recovery means ‘regaining vitality and life force’ (Tse et al. 2012). An alternative translation is 復原 (fu yuan), or restoration to an original state, and a third is 復圓 (fu yuan), which involves the broader idea of regaining fullness and completeness. Although all three have the same English phonic, they differ in nuance.

Well-developed understandings of recovery and well-being exist in non-western cultures. For example, the identity of indigenous Australian people is interwoven with the physical world (Flood, 1991). Spiritual identity is shared with the land, a description of reality which clearly incorporates a concept of identity quite different from western psychological, sociological and philosophical understandings. Similarly, Native American Indian conceptions of health involve a relational or cyclical world-view, balancing context, mind, body and spirit (Cross et al. 2000). Māori and Pacific Islanders in New Zealand also have a cultural identity influenced by Whānau Ora – the diverse families embedded in the culture (Lapsley et al. 2002).

The absence of any substantial reference to these conceptualisations in English-language publications reinforces the concerns raised by others about the wider cultural applicability of ‘recovery’ (O'Hagan, 2004). Some question the focus on individuality: ‘the recovery approach seems to have taken us in an individualising and personalising direction,’ with a danger of ‘losing contact with the strength that people gain from each other, and the value of communities’ (Mind, 2008, p. 11). Others are concerned about the embedded socio-political assumptions: ‘I believe that current transnational forms of organizing social relations are both cultures of compliance and cultures of constraint … these global forces reconstruct people's identities so that they are given few social options for agency. There is a trend in the “recovery” movement to, at best, a constraining and, at worst, an oppressive set of social discourses and relations…the language of “recovery” needs to be questioned for its congruency with the type of social actor that is required for the successful spread of the global market economy’ (Mental Health ‘Recovery’ Study Working Group, 2009, p. 32). These concerns lead some – especially from within the service user movement – to an oppositional stance: ‘The “recovery” movement is dangerous if it stays solely focused on the adjustment of the individual to social forces by “recovering”’ (Mental Health ‘Recovery’ Study Working Group, 2009, p. 33).

One approach to avoiding a monocultural understanding of recovery will be to enlarge the scientific evidence base from non-western countries and from non-majority populations. For example, studies investigating recovery in Black and Minority Ethnic mental health service users identified a greater emphasis on spirituality, stigma, culture-specific factors and collectivist notions of identity (Leamy et al. 2011).

Evidence gaps

This study shows that the scientific foundation of recovery models and frameworks remains primarily qualitative studies and expert opinion. These forms of evidence are relatively low in the evidence-based medicine hierarchy. This points to the need for a more quantitative evidence base (Slade & Hayward, 2007), involving the use of standardised measures of recovery (Poloni et al. 2010). We identify three key knowledge gaps.

First, how does recovery unfold over time? A number of stage models have been proposed (Leamy et al. 2011), and these can be mapped onto the change model described in the Transtheoretical Model (Prochaska & Di Clemente, 1982). However, they are mainly based on evidence that is qualitative, retrospective and self-reported. Prospective, quantitative and multi-perspective evaluations are lacking. Empirical data about changes over time in the experience of recovery will inform both models and interventions. This might involve using mixed methods, such as a multivariate repeated measures design using quantitative standardised measures completed by the service user, their family member and their clinician, alongside a diary study. This design would also allow empirical investigation of the relationship between the stage of recovery and the five CHIME processes.

Second, debates about the contribution of mental health services to recovery continue, and are often polarised and non-evidence based. It is plausible to expect that the contribution of services to recovery varies both between individuals and within individuals over time, so there will be no single answer. It is also clear that the process of care is more than simply a vehicle for providing evidence-based treatments, but rather an active contribution to people's recovery (Davidson et al. 2008a). More broadly, best available evidence drawn from international guidelines suggests that mental health systems can support recovery in relation to four domains of practice: promoting citizenship, organisational commitment, supporting personally defined recovery and working relationships (Le Boutillier et al. 2011). Empirical evidence about the relative contribution of mental health services and other sources of support for recovery will inform this debate (Slade, 2010a).

Finally, quantitative approaches are needed to evaluate interventions that support recovery, and to understand the relationship between changes in recovery domains (e.g. CHIME) and clinical domains of outcome. These questions are being evaluated in the REFOCUS randomised controlled trial (Slade et al. 2011).

Although not within the scope of the current review, it is worth noting that the scientific evidence base for recovery is slowly growing. Systematic reviews (Doughty & Tse, 2005; Leamy et al. 2011), randomised controlled trials (Greenfield et al. 2008; Barbic et al. 2009), intervention manuals (Clarke et al. 2006; Bird et al. 2011), scholarly overviews (Slade, 2009c; Andresen et al. 2011) and practice guides (Davidson et al. 2009; Slade, 2009a) all contribute to an emerging evidence base for recovery practice and outcomes. Consensus on best practice internationally is now emerging (Compagni et al. 2007; Le Boutillier et al. 2011), and links are being established with a wider and related literature on topics such as person-centred planning (Adams & Grieder, 2005), positive psychology (Resnick & Rosenheck, 2006) and well-being (Slade, 2010b). A key challenge in the development of this evidence base is ensuring that those people directly affected by the research – people who use mental health services and their carers – are involved as partners in the development of scientific knowledge, either through direct co-production (Boyle & Harris, 2009) or through collaboration (Slade et al. 2010).

Differences between countries

At the top level of the coding framework, there was no great variation between countries. This suggests that, at least within English-speaking countries, the five CHIME dimensions do capture key aspects of recovery, and can be recommended as the basis for a common understanding, with the caveat of the monocultural concern noted earlier.

At the second level of coding, differences emerge. Connectedness sub-categories were most densely coded in the USA and UK, reflecting their focus on community integration and social inclusion, respectively. The importance placed on meaning in life was somewhat higher in the UK and Canada. Finally, a marked emphasis on strengths was present in Australia. This relates to two developments being implemented across the country: the Strengths Model (Rapp & Goscha, 2006) and the Collaborative Recovery Model (Oades et al. 2005), both of which have a strong empirical evidence base. A focus on strengths is for example prominent in a recent framework for recovery-oriented practice published in Victoria, Australia (Department of Health, 2011).

Limitations

The study has at least five limitations. First, the CHIME framework is based on secondary analysis presented in each source paper, rather than considering the primary data directly. Second, the emergent categories were only one way of grouping the findings, so the CHIME Framework could be amended if the narrative synthesis were repeated. Third, the country of origin for reviews may not reflect the often international sources of data informing the presented model. Fourth, the restriction to English-language papers means that the development of frameworks for recovery in other languages is unknown. Finally, and as with the original review, the CHIME framework should not be seen as definitive. Recovery is an individual and dynamic process, and this review is not intended to be a rigid definition of what recovery ‘is’, but rather a resource to inform future research and clinical practice.

The main finding is that current conceptualisations of recovery are primarily based on Western European and North American models, and a broader scientific evidence base is needed. The incorporation of recovery ideas into non-English speaking countries is underway (Tse et al. 2012) but this needs to be a two-way process: research from culturally more dissimilar countries would help to highlight both embedded social and political assumptions about the nature of recovery, and the individualistic rather than collectivist focus of current models of recovery.

Declaration of Interest

This study was funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grant for Applied Research (RP-PG-0707-10040) awarded to the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, and in relation to the NIHR Specialist Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams N, Grieder DM (2005). Treatment Planning for Person-Centered Care. Elsevier: Burlington, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Amering M, Schmolke M (2007). Recovery. Das Ende der Unheilbarkeit. Psychiatrie-Verlag: Bonn. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen R, Oades L, Caputi P (2011). Psychological Recovery: Beyond Mental Illness. John Wiley: London. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA (1993). Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health system in the 1990s. Innovations and Research 2, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson H (2011). Recovered or dead? A Swedish study of 321 persons surveyed as severely mentally ill in 1995/96 but not so ten years later. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 20, 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundsdottir EE (2009). Creation of new services: collaboration between mental health consumers and occupational therapists. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health 25, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Barbic S, Krupa T, Armstrong I (2009). A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a modified recovery workbook program: preliminary findings. Psychiatric Services 60, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellack A (2006). Scientific and consumer models of recovery in schizophrenia: concordance, contrasts, and implications. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32, 432–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird V, Leamy M, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M (2011). REFOCUS: Promoting Recovery in Community Mental Health Services. Rethink (researchintorecovery.com/refocus): London. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle D, Harris M (2009). The Challenge of Co-production. New Economics Foundation: London. [Google Scholar]

- Care Services Improvement Partnership, RCoP, Social Care Institute for Excellence (2007). A Common Purpose: Recovery in Future Mental Health Services. CSIP: Leeds. [Google Scholar]

- Clark J (2003). How to peer review a qualitative manuscript In Peer Review in Health Sciences (ed. Godlee F and Jefferson T), pp. 219–235. BMJ Books: London. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SP, Oades LG, Crowe T, Deane F (2006). Collaborative goal technology: theory and practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 30, 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagni A, Adams N, Daniels A (2007). International Pathways to Mental Health System Transformation: Strategies and Challenges. California Institute for Mental Health: California. [Google Scholar]

- Cross T, Earle K, Echo-Hawk-Solie H, Manness K (2000). Cultural strengths and challenges in implementing a system of care model in American Indian communities Systems of Care: Promising Practices in Children's Mental Health, 2000 Series, 1, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Miller R, Flanagan E (2008a). What's in it for me? The utility of psychiatric treatments from the perspective of the person in recovery. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 17, 177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Schmutte T, Dinzeo T, Andres-Hyman R (2008b). Remission and recovery in schizophrenia: practitioner and patient perspectives. Schizophrenia Bulletin 34, 5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Tondora J, Lawless MS, O'Connell M, Rowe M (2009). A Practical Guide to Recovery-Oriented Practice Tools for Transforming Mental Health Care. Oxford University Press: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Rakfeldt J, Strauss J (2010a). The Roots of the Recovery Movement in Psychiatry. Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Roe D, Andres-Hyman R, Ridgway P (2010b). Applying stages of change models to recovery from serious mental illness: contributions and limitations. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences 47, 2010–2221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2011). Framework for Recovery-oriented Practice. Mental Health, Drugs and Regions Division: Melbourne. [Google Scholar]

- Dilks S, Tasker F, Wren B (2010). Managing the impact of psychosis: a grounded theory exploration of recovery processes in psychosis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 49, 1–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty C, Tse S (2005). The Effectiveness of Service User-run or Service User-led Mental Health Services for People with Mental Illness: A Systematic Literature Review. Mental Health Commission: Wellington. [Google Scholar]

- EPHPP (1998). Effective Public Health Practice Project http://www.ephpp.ca/index.html.

- Flood J (1991). Archaeology of the Dreamtime: The Story of Prehistoric Australia and Its People. Collins: Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Green T, Batson A, Gudjonsson G (2011). The development and initial validation of a service-user led measure for recovery of mentally disordered offenders. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology 22, 252–265. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Stoneking BC, Humphreys K, Sundby E, Bond J (2008). A randomized trial of a mental health consumer-managed alternative to civil commitment for acute psychiatric crisis. American Journal of Community Psychology 42, 135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm AL, Severinsson E (2011). Struggling to recover by changing suicidal behaviour: narratives from women with borderline personality disorder. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 20, 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartalova-O'Doherty Y, Tedstone Doherty D (2010). Recovering from recurrent mental health problems: giving up and fighting to get better. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 19, 3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M, Lamont S, Brunero S (2010). An occupational perspective of the recovery journey in mental health. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 73, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kogstad RE, Ekeland TJ, Hummelvoll JK (2011). In defence of a humanistic approach to mental health care: recovery processes investigated with the help of clients' narratives on turning points and processes of gradual change. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 18, 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapsley H, Nikora LW, Black R (2002). Kia Mauri Tau! Narratives of Recovery from Disabling Mental Health Problems. Mental Health Commission: Wellington. [Google Scholar]

- Le Boutillier C, Leamy M, Bird VJ, Davidson L, Williams J, Slade M (2011). What does recovery mean in practice? A qualitative analysis of international recovery-oriented practice guidance. Psychiatric Services 62, 1470–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M (2011). A conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. British Journal of Psychiatry 199, 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libermann RP, Kopelowicz A (2002). Recovery from schizophrenia: a challenge for the 21st century. International Review of Psychiatry 14, 242–255. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell W, Powell S, Pedley R, Thomas N, Jones SA (2010). The process of recovery from bipolar 1 disorder: a qualitative analysis of personal accounts in relation to an integrative cognitive model. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 49, 193–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead S (2005). Intentional Peer Support: An Alternative Approach. Shery Mead Consulting: Plainfield, NH. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health ‘Recovery’ Study Working Group (2009). Mental Health ‘Recovery’: Users and Refusers. Wellesley Institute: Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Mezey GC, Kavuma M, Turton P, Demetriou A, Wright C (2010). Perceptions, experiences and meanings of recovery in forensic psychiatric patients. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology 21, 2010–2696. [Google Scholar]

- Mind (2008). Life and Times of a Supermodel. The Recovery Paradigm for Mental Health. Mind: London. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009). The Guidelines Manual. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: London. [Google Scholar]

- Noiseux S, Tribble St-Cyr D, Corin E, St-Hilaire PL, Morissette R, Leclerc C, Fleury D, Vigneault L, Gagnier F (2010). The process of recovery of people with mental illness: the perspectives of patients, family members and care providers: part 1. BMC Health Services Research 10, 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oades L, Deane F, Crowe T, Lambert WG, Kavanagh D, Lloyd C (2005). Collaborative recovery: an integrative model for working with individuals who experience chronic and recurring mental illness. Australasian Psychiatry 13, 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hagan M (2004). Recovery in New Zealand: lessons from Australia? Australian e-journal for the Advancement of Mental Health 3 (http://www.auseinet.com/journal/vol3iss1/ohaganeditorial.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- Onken SJ, Craig CM, Ridgway P, Ralph RO, Cook JA (2007). An analysis of the definitions and elements of recovery: a review of the literature. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 31, 9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poloni N, Callegari C, Buzzi A, Aletti F, Beranzini F, Vecchi F, Vender S (2010). [The Italian version of ISOS and RSQ, two suitable scales for investigating recovery style from psychosis]. Validazione della versione italiana delle Scale ISOS e RSQ per lo studio del recovery style nei disturbi psicotici. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 19, 352–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S (2006). Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. Results of an ESRC Funded Research Project (Unpublished Report) University of Lancaster: Lancaster. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Di Clemente CC (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 19, 276–288. [Google Scholar]

- Ralph RO (2000). Recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 4, 480–517. [Google Scholar]

- Ralph RO (2005). Verbal definitions and visual models of recovery: focus on the recovery model In Recovery in Mental Illness. Broadening Our Understanding of Wellness (ed. Ralph RO and Corrigan PW), pp. 131–145. American Psychological Association: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Ramon S, Healy B, Renouf N (2007). Recovery from Mental Illness as an Emergent Concept and Practice in Australia and the UK. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 53, 108–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp C, Goscha RJ (2006). The Strengths Model: Case Management With People With Psychiatric Disabilities. 2nd edn. Oxford University Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SG, Rosenheck RA (2006). Recovery and positive psychology: Parallel themes and potential synergies. Psychiatric Services 57, 120–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano DM, McCay E, Goering P, Boydell K, Zipursky R (2010). Reshaping an enduring sense of self: the process of recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 4, 243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romme M, Escher S, Dillon J, Corstens D, Morris M (2009). Living with Voices: 50 Stories of Recovery. PCCS: Ross-on-Wye. [Google Scholar]

- Schön U (2010). Recovery from severe mental illness, a gender perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 24, 557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrank B, Slade M (2007). Recovery in psychiatry. Psychiatric Bulletin 31, 321–325. [Google Scholar]

- Secker J, Membrey H, Grove B, Seebohm P (2002). Recovering from Illness or recovering your life? Implications of clinical versus social models of recovery from mental health problems for employment support services. Disability and Society 17, 403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Semisa D, Casacchia M, Di Munzio W, Neri G, Buscaglia G, Burti L, Pucci C, Corlito G, Bacigalupi M, Parravani R, Roncone R, Cristofalo D, Lora A, Ruggeri M, Gruppo S-DS, Asioli F, Balbi A, Buscaglia C, Carra G, Erlicher A, Lasalvia A, Marinoni A, Miceli M, Morganti C, Morosini P, Iacchetti D, Pegoraro M, Scavo V, Alderighi M, Lorenzo P, Lecci F, Tanini A, Cefali T, Caneschi A, Ottanelli R, Magnani N, Bardicchia F, Pescosolido R, Allevi L, Ferrigno J, Giusto G, Rolando P, Dall'Agnola R, Bissoli S, Cassano AM, Ciampolillo G, Fracchiolla P, Lupoi S, Visani E, Pismataro CP, Mari L, Gazale MF, Bianchi I, Milano MC, Amideo F, Basile F, Santelia S, Vanetti M, Carnevale L, Debernardi C, Fiorica L, Pollice R, Cavicchio A, Pioli R, Cicolella G, Riva E, Pismataro CP, Leng G, Levav I, Losavio T, Maj M, Pilling S, Saxena S, Tansella M (2008). [Promoting recovery of schizophrenic patients: discrepancy between routine practice and evidence. The SIEP-DIRECT'S Project]. Promuovere il recupero dei pazienti con schizofrenia: discrepanze fra pratiche di routine ed evidenze. Il Progetto SIEP-DIRECT'S. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 17, 331–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M (2009a). 100 Ways to Support Recovery. Rethink (rethink.org/100ways): London. [Google Scholar]

- Slade M (2009b). The contribution of mental health services to recovery. Journal of Mental Health 18, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Slade M (2009c). Personal Recovery and Mental Illness. A Guide for Mental Health Professionals. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Slade M (2010a). Measuring recovery in mental health services. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences 47, 206–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M (2010b). Mental illness and well-being: the central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Services Research 10, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M, Hayward M (2007). Recovery, psychosis and psychiatry: research is better than rhetoric. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 116, 81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M, Amering M, Oades L (2008). Recovery: an international perspective. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 17, 128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M, Bird V, Chandler R, Fox J, Larsen J, Tew J, Leamy M (2010). The contribution of advisory committees and public involvement to large studies: case study. BMC Health Services Research 10, 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, McCrone P, Leamy M (2011). REFOCUS Trial: protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial of a pro-recovery intervention within community based mental health teams. BMC Psychiatry 11, 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M, Adams N, O'Hagan M (2012). Recovery: past progress and future challenges. International Review of Psychiatry 24, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song LY, Shih CY (2009). Factors, process and outcome of recovery from psychiatric disability the utility model. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 55, 348–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (2010). Social Inclusion and Recovery (SIR) Strategy 2010–2015. SLAM: London. [Google Scholar]

- Stickley T, Wright N (2011a). The British research evidence for recovery, papers published between 2006 and 2009 (inclusive). Part One: a review of the peer-reviewed literature using a systematic approach. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 18, 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickley T, Wright N (2011b). The British research evidence for recovery, papers published between 2006 and 2009 (inclusive). Part Two: a review of the grey literature including book chapters and policy documents. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 18, 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung KM, Kim S, Puskar KR, Kim E (2006). Comparing life experiences of college students with differing courses of schizophrenia in Korea: case studies. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 42, 82–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse S, Cheung E, Kan A, Ng R, Yau S (2012). Recovery in Hong Kong: Service user participation in mental health services. International Review of Psychiatry 24, 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turton P, Demetriou A, Boland W, Gillard S, Kavuma M, Mezey G, Mountford V, Turner K, White S, Zadeh E, Wright C (2011). One size fits all: or horses for courses? Recovery-based care in specialist mental health services. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 46, 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel-Scibilia SE, McNulty KC, Baxter B, Miller S, Dine M, Frese III FJ (2009). The recovery process utilizing Erikson's stages of human development. Community Mental Health Journal 45, 405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood L, Price J, Morrison A, Haddock G (2010). Conceptualisation of recovery from psychosis: A service-user perspective. Psychiatrist 34, 465–470. [Google Scholar]