Abstract

Background

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States. More and more states legalized medical and recreational marijuana use. Adolescents and emerging adults are at high risk for marijuana use. This ecological study aims to examine historical trends in marijuana use among youth along with marijuana legalization.

Method

Data (n = 749,152) were from the 31-wave National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 1979–2016. Current marijuana use, if use marijuana in the past 30 days, was used as outcome variable. Age was measured as the chronological age self-reported by the participants, period was the year when the survey was conducted, and cohort was estimated as period subtracted age. Rate of current marijuana use was decomposed into independent age, period and cohort effects using the hierarchical age-period-cohort (HAPC) model.

Results

After controlling for age, cohort and other covariates, the estimated period effect indicated declines in marijuana use in 1979–1992 and 2001–2006, and increases in 1992–2001 and 2006–2016. The period effect was positively and significantly associated with the proportion of people covered by Medical Marijuana Laws (MML) (correlation coefficients: 0.89 for total sample, 0.81 for males and 0.93 for females, all three p values < 0.01), but was not significantly associated with the Recreational Marijuana Laws (RML). The estimated cohort effect showed a historical decline in marijuana use in those who were born in 1954–1972, a sudden increase in 1972–1984, followed by a decline in 1984–2003.

Conclusion

The model derived trends in marijuana use were coincident with the laws and regulations on marijuana and other drugs in the United States since the 1950s. With more states legalizing marijuana use in the United States, emphasizing responsible use would be essential to protect youth from using marijuana.

Keywords: Marijuana, Adolescents and young adults, HAPC model, United States

Introduction

Marijuana use and laws in the United States

Marijuana is one of the most commonly used drugs in the United States (US) [1]. In 2015, 8.3% of the US population aged 12 years and older used marijuana in the past month; 16.4% of adolescents aged 12–17 years used in lifetime and 7.0% used in the past month [2]. The effects of marijuana on a person’s health are mixed. Despite potential benefits (e.g., relieve pain) [3], using marijuana is associated with a number of adverse effects, particularly among adolescents. Typical adverse effects include impaired short-term memory, cognitive impairment, diminished life satisfaction, and increased risk of using other substances [4].

Since 1937 when the Marijuana Tax Act was issued, a series of federal laws have been subsequently enacted to regulate marijuana use, including the Boggs Act (1952), Narcotics Control Act (1956), Controlled Substance Act (1970), and Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [5, 6]. These laws regulated the sale, possession, use, and cultivation of marijuana [6]. For example, the Boggs Act increased the punishment of marijuana possession, and the Controlled Substance Act categorized the marijuana into the Schedule I Drugs which have a high potential for abuse, no medical use, and not safe to use without medical supervision [5, 6]. These federal laws may have contributed to changes in the historical trend of marijuana use among youth.

Movements to decriminalize and legalize marijuana use

Starting in the late 1960s, marijuana decriminalization became a movement, advocating reformation of federal laws regulating marijuana [7]. As a result, 11 US states had taken measures to decriminalize marijuana use by reducing the penalty of possession of small amount of marijuana [7].

The legalization of marijuana started in 1993 when Surgeon General Elder proposed to study marijuana legalization [8]. California was the first state that passed Medical Marijuana Laws (MML) in 1996 [9]. After California, more and more states established laws permitting marijuana use for medical and/or recreational purposes. To date, 33 states and the District of Columbia have established MML, including 11 states with recreational marijuana laws (RML) [9]. Compared with the legalization of marijuana use in the European countries which were more divided that many of them have medical marijuana registered as a treatment option with few having legalized recreational use [10–13], the legalization of marijuana in the US were more mixed with 11 states legalized medical and recreational use consecutively, such as California, Nevada, Washington, etc. These state laws may alter people’s attitudes and behaviors, finally may lead to the increased risk of marijuana use, particularly among young people [13]. Reported studies indicate that state marijuana laws were associated with increases in acceptance of and accessibility to marijuana, declines in perceived harm, and formation of new norms supporting marijuana use [14].

Marijuana harm to adolescents and young adults

Adolescents and young adults constitute a large proportion of the US population. Data from the US Census Bureau indicate that approximately 60 million of the US population are in the 12–25 years age range [15]. These people are vulnerable to drugs, including marijuana [16]. Marijuana is more prevalent among people in this age range than in other ages [17]. One well-known factor for explaining the marijuana use among people in this age range is the theory of imbalanced cognitive and physical development [4]. The delayed brain development of youth reduces their capability to cognitively process social, emotional and incentive events against risk behaviors, such as marijuana use [18]. Understanding the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use among this population with a historical perspective is of great legal, social and public health significance.

Inconsistent results regarding the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use

A number of studies have examined the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use across the world, but reported inconsistent results [13]. Some studies reported no association between marijuana laws and marijuana use [14, 19–25], some reported a protective effect of the laws against marijuana use [24, 26], some reported mixed effects [27, 28], while some others reported a risk effect that marijuana laws increased marijuana use [29, 30]. Despite much information, our review of these reported studies revealed several limitations. First of all, these studies often targeted a short time span, ignoring the long period trend before marijuana legalization. Despite the fact that marijuana laws enact in a specific year, the process of legalization often lasts for several years. Individuals may have already changed their attitudes and behaviors before the year when the law is enacted. Therefore, it may not be valid when comparing marijuana use before and after the year at a single time point when the law is enacted and ignoring the secular historical trend [19, 30, 31]. Second, many studies adapted the difference-in-difference analytical approach designated for analyzing randomized controlled trials. No US state is randomized to legalize the marijuana laws, and no state can be established as controls. Thus, the impact of laws cannot be efficiently detected using this approach. Third, since marijuana legalization is a public process, and the information of marijuana legalization in one state can be easily spread to states without the marijuana laws. The information diffusion cannot be ruled out, reducing the validity of the non-marijuana law states as the controls to compare the between-state differences [31].

Alternatively, evidence derived based on a historical perspective may provide new information regarding the impact of laws and regulations on marijuana use, including state marijuana laws in the past two decades. Marijuana users may stop using to comply with the laws/regulations, while non-marijuana users may start to use if marijuana is legal. Data from several studies with national data since 1996 demonstrate that attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, and use of marijuana among people in the US were associated with state marijuana laws [29, 32].

Age-period-cohort modeling: looking into the past with recent data

To investigate historical trends over a long period, including the time period with no data, we can use the classic age-period-cohort modeling (APC) approach. The APC model can successfully discompose the rate or prevalence of marijuana use into independent age, period and cohort effects [33, 34]. Age effect refers to the risk associated with the aging process, including the biological and social accumulation process. Period effect is risk associated with the external environmental events in specific years that exert effect on all age groups, representing the unbiased historical trend of marijuana use which controlling for the influences from age and birth cohort. Cohort effect refers to the risk associated with the specific year of birth. A typical example is that people born in 2011 in Fukushima, Japan may have greater risk of cancer due to the nuclear disaster [35], so a person aged 80 in 2091 contains the information of cancer risk in 2011 when he/she was born. Similarly, a participant aged 25 in 1979 contains information on the risk of marijuana use 25 years ago in 1954 when that person was born. With this method, we can describe historical trends of marijuana use using information stored by participants in older ages [33]. The estimated period and cohort effects can be used to present the unbiased historical trend of specific topics, including marijuana use [34, 36–38]. Furthermore, the newly established hierarchical APC (HAPC) modeling is capable of analyzing individual-level data to provide more precise measures of historical trends [33]. The HAPC model has been used in various fields, including social and behavioral science, and public health [39, 40].

Several studies have investigated marijuana use with APC modeling method [17, 41, 42]. However, these studies covered only a small portion of the decades with state marijuana legalization [17, 42]. For example, the study conducted by Miech and colleagues only covered periods from 1985 to 2009 [17]. Among these studies, one focused on a longer state marijuana legalization period, but did not provide detailed information regarding the impact of marijuana laws because the survey was every 5 years and researchers used a large 5-year age group which leads to a wide 10-year birth cohort. The averaging of the cohort effects in 10 years could reduce the capability of detecting sensitive changes of marijuana use corresponding to the historical events [41].

Purpose of the study

In this study, we examined the historical trends in marijuana use among youth using HAPC modeling to obtain the period and cohort effects. These two effects provide unbiased and independent information to characterize historical trends in marijuana use after controlling for age and other covariates. We conceptually linked the model-derived time trends to both federal and state laws/regulations regarding marijuana and other drug use in 1954–2016. The ultimate goal is to provide evidence informing federal and state legislation and public health decision-making to promote responsible marijuana use and to protect young people from marijuana use-related adverse consequences.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study population

Data were derived from 31 waves of National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 1979–2016. NSDUH is a multi-year cross-sectional survey program sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The survey was conducted every 3 years before 1990, and annually thereafter. The aim is to provide data on the use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drug and mental health among the US population.

Survey participants were noninstitutionalized US civilians 12 years of age and older. Participants were recruited by NSDUH using a multi-stage clustered random sampling method. Several changes were made to the NSDUH after its establishment [43]. First, the name of the survey was changed from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) to NSDUH in 2002. Second, starting in 2002, adolescent participants receive $30 as incentives to improve the response rate. Third, survey mode was changed from personal interviews with self-enumerated answer sheets (before 1999) to the computer-assisted person interviews (CAPI) and audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) (since 1999). These changes may confound the historical trends [43], thus we used two dummy variables as covariates, one for the survey mode change in 1999 and another for the survey method change in 2002 to control for potential confounding effect.

Data acquisition

Data were downloaded from the designated website (https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm). A database was used to store and merge the data by year for analysis. Among all participants, data for those aged 12–25 years (n = 749,152) were included. We excluded participants aged 26 and older because the public data did not provide information on single or two-year age that was needed for HAPC modeling (details see statistical analysis section). We obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida to conduct this study.

Variables and measurements

Current marijuana use: the dependent variable. Participants were defined as current marijuana users if they reported marijuana use within the past 30 days. We used the variable harmonization method to create a comparable measure across 31-wave NSDUH data [44]. Slightly different questions were used in NSDUH. In 1979–1993, participants were asked: “When was the most recent time that you used marijuana or hash?” Starting in 1994, the question was changed to “How long has it been since you last used marijuana or hashish?” To harmonize the marijuana use variable, participants were coded as current marijuana users if their response to the question indicated the last time to use marijuana was within past 30 days.

Chronological age, time period and birth cohort were the predictors. (1) Chronological age in years was measured with participants’ age at the survey. APC modeling requires the same age measure for all participants [33]. Since no data by single-year age were available for participants older than 21, we grouped all participants into two-year age groups. A total of 7 age groups, 12–13, ..., 24–25 were used. (2) Time period was measured with the year when the survey was conducted, including 1979, 1982, 1985, 1988, 1990, 1991... 2016. (3). Birth cohort was the year of birth, and it was measured by subtracting age from the survey year.

The proportion of people covered by MML: This variable was created by dividing the population in all states with MML over the total US population. The proportion was computed by year from 1996 when California first passed the MML to 2016 when a total of 29 states legalized medical marijuana use. The estimated proportion ranged from 12% in 1996 to 61% in 2016. The proportion of people covered by RML: This variable was derived by dividing the population in all states with RML with the total US population. The estimated proportion ranged from 4% in 2012 to 21% in 2016. These two variables were used to quantitatively assess the relationships between marijuana laws and changes in the risk of marijuana use.

Covariates: Demographic variables gender (male/female) and race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic and others) were used to describe the study sample.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the prevalence of current marijuana use by year using the survey estimation method, considering the complex multi-stage cluster random sampling design and unequal probability. A prevalence rate is not a simple indicator, but consisting of the impact of chronological age, time period and birth cohort, named as age, period and cohort effects, respectively. Thus, it is biased if a prevalence rate is directly used to depict the historical trend. HAPC modeling is an epidemiological method capable of decomposing prevalence rate into mutually independent age, period and cohort effects with individual-level data, while the estimated period and cohort effects provide an unbiased measure of historical trend controlling for the effects of age and other covariates. In this study, we analyzed the data using the two-level HAPC cross-classified random-effects model (CCREM) [36]:

| 1 |

Where Mijk represents the rate of marijuana use for participants in age group i (12–13, 14,15...), period j (1979, 1982,...) and birth cohort k (1954–55, 1956–57...); parameter αi (age effect) was modeled as the fixed effect; and parameters βj (period effect) and γk (cohort effect) were modeled as random effects; and βm was used to control m covariates, including the two dummy variables assessing changes made to the NSDUH in 1999 and 2002, respectively.

The HAPC modeling analysis was executed using the PROC GLIMMIX. Sample weights were included to obtain results representing the total US population aged 12–25. A ridge-stabilized Newton-Raphson algorithm was used for parameter estimation. Modeling analysis was conducted for the overall sample, stratified by gender. The estimated age effect αi, period βj and cohort γk (i.e., the log-linear regression coefficients) were directly plotted to visualize the pattern of change.

To gain insight into the relationship between legal events and regulations at the national level, we listed these events/regulations along with the estimated time trends in the risk of marijuana from HAPC modeling. To provide a quantitative measure, we associated the estimated period effect with the proportions of US population living with MML and RML using Pearson correlation. All statistical analyses for this study were conducted using the software SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Sample characteristics

Data for a total of 749,152 participants (12–25 years old) from all 31-wave NSDUH covering a 38-year period were analyzed. Among the total sample (Table 1), 48.96% were male and 58.78% were White, 14.84% Black, and 18.40% Hispanic.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample, overall, by gender and by race/ethnicity, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 1979–2016

| Period | Total | Gender | Race/Ethnicity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | White | Black | Hispanic | Others | ||

| 1979 | 4209 | 2063 | 2146 | 3350 | 490 | 244 | 125 |

| 1982 | 2864 | 1404 | 1460 | 2263 | 358 | 169 | 74 |

| 1985 | 4042 | 1919 | 2123 | 1790 | 1049 | 1158 | 45 |

| 1988 | 4600 | 2199 | 2401 | 2218 | 1067 | 1217 | 98 |

| 1990 | 4229 | 2028 | 2201 | 2262 | 862 | 974 | 131 |

| 1991 | 15,942 | 7465 | 8477 | 7335 | 4068 | 3946 | 593 |

| 1992 | 14,975 | 7124 | 7851 | 6668 | 3606 | 4053 | 648 |

| 1993 | 12,509 | 6121 | 6388 | 5516 | 2914 | 3573 | 506 |

| 1994 | 10,425 | 5072 | 5353 | 4950 | 2313 | 2892 | 270 |

| 1995 | 8558 | 4074 | 4484 | 3979 | 2048 | 2260 | 271 |

| 1996 | 8904 | 4017 | 4887 | 3950 | 2207 | 2438 | 309 |

| 1997 | 14,083 | 6627 | 7456 | 6936 | 2408 | 3949 | 790 |

| 1998 | 14,096 | 6658 | 7438 | 6017 | 3172 | 4056 | 851 |

| 1999 | 35,766 | 17,514 | 18,252 | 24,182 | 4705 | 4785 | 2094 |

| 2000 | 37,293 | 18,351 | 18,942 | 25,035 | 4794 | 5206 | 2258 |

| 2001 | 35,090 | 17,182 | 17,908 | 23,400 | 4557 | 4841 | 2292 |

| 2002 | 35,437 | 17,320 | 18,117 | 23,534 | 4698 | 4946 | 2259 |

| 2003 | 36,587 | 18,210 | 18,377 | 23,162 | 4934 | 5597 | 2894 |

| 2004 | 36,769 | 17,991 | 18,778 | 23,344 | 4843 | 5579 | 3003 |

| 2005 | 37,154 | 18,067 | 19,087 | 23,080 | 4938 | 6062 | 3074 |

| 2006 | 36,246 | 17,974 | 18,272 | 22,137 | 5060 | 6041 | 3008 |

| 2007 | 36,044 | 17,851 | 18,193 | 21,908 | 4719 | 6168 | 3249 |

| 2008 | 36,495 | 18,021 | 18,474 | 21,546 | 4998 | 6523 | 3428 |

| 2009 | 36,288 | 17,793 | 18,495 | 21,404 | 4959 | 6426 | 3499 |

| 2010 | 37,469 | 18,512 | 18,957 | 22,331 | 5003 | 6602 | 3533 |

| 2011 | 38,447 | 19,165 | 19,282 | 22,564 | 5306 | 6907 | 3670 |

| 2012 | 36,014 | 17,720 | 18,294 | 20,640 | 4901 | 6909 | 3564 |

| 2013 | 35,878 | 17,642 | 18,236 | 20,114 | 4999 | 6938 | 3827 |

| 2014 | 26,669 | 13,176 | 13,493 | 14,691 | 3533 | 5426 | 3019 |

| 2015 | 28,138 | 13,688 | 14,450 | 14,940 | 3834 | 6118 | 3246 |

| 2016 | 27,932 | 13,822 | 14,110 | 15,140 | 3809 | 5876 | 3107 |

Prevalence rate of current marijuana use

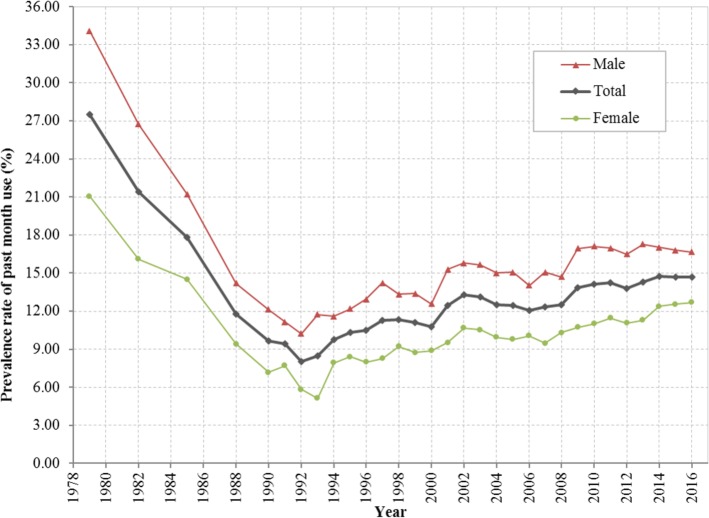

As shown in Fig. 1, the estimated prevalence rates of current marijuana use from 1979 to 2016 show a “V” shaped pattern. The rate was 27.57% in 1979, it declined to 8.02% in 1992, followed by a gradual increase to 14.70% by 2016. The pattern was the same for both male and female with males more likely to use than females during the whole period.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence rate (%) of current marijuana use among US residents 12 to 25 years of age during 1979–2016, overall and stratified by gender. Derived from data from the 1979–2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

HAPC modeling and results

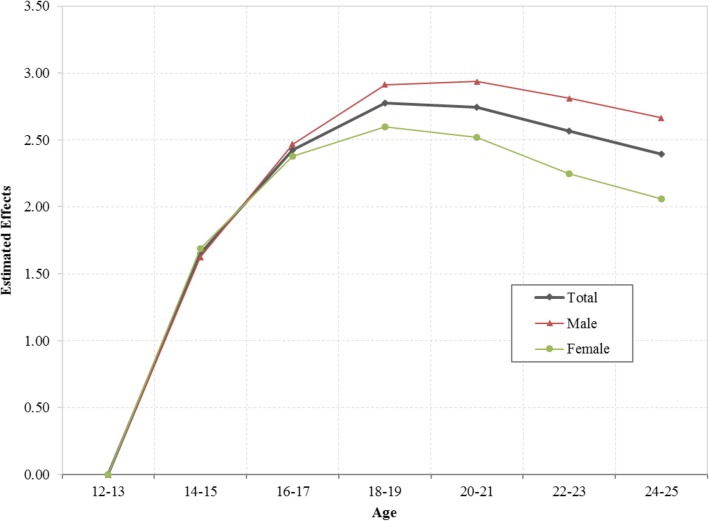

Estimated age effects αi from the CCREM [1] for current marijuana use are presented in Fig. 2. The risk by age shows a 2-phase pattern –a rapid increase phase from ages 12 to 19, followed by a gradually declining phase. The pattern was persistent for the overall sample and for both male and female subsamples.

Fig. 2.

Age effect for the risk of current marijuana use, overall and stratified by male and female, estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method with 31 waves of NSDUH data during 1979–2016. Age effect αi were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

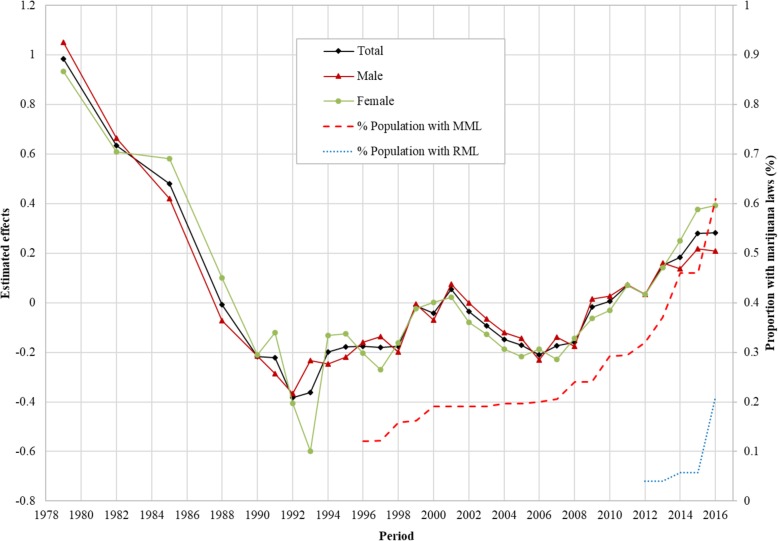

The estimated period effects βj from the CCREM [1] are presented in Fig. 3. The period effect reflects the risk of current marijuana use due to significant events occurring over the period, particularly federal and state laws and regulations. After controlling for the impacts of age, cohort and other covariates, the estimated period effect indicates that the risk of current marijuana use had two declining trends (1979–1992 and 2001–2006), and two increasing trends (1992–2001 and 2006–2016). Epidemiologically, the time trends characterized by the estimated period effects in Fig. 3 are more valid than the prevalence rates presented in Fig. 1 because the former was adjusted for confounders while the later was not.

Fig. 3.

Period effect for the risk of marijuana use for US adolescents and young adults, overall and by male/female estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method and its correlation with the proportion of US population covered by Medical Marijuana Laws and Recreational Marijuana Laws. Period effect βj were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

Correlation of the period effect with proportions of the population covered by marijuana laws: The Pearson correlation coefficient of the period effect with the proportions of US population covered by MML during 1996–2016 was 0.89 for the total sample, 0.81 for male and 0.93 for female, respectively (p < 0.01 for all). The correlation between period effect and proportion of US population covered by RML was 0.64 for the total sample, 0.59 for male and 0.49 for female (p > 0.05 for all).

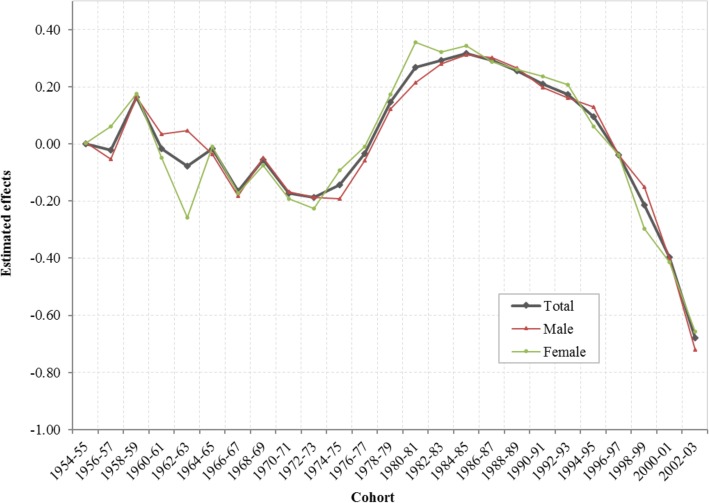

Likewise, the estimated cohort effects γk from the CCREM [1] are presented in Fig. 4. The cohort effect reflects changes in the risk of current marijuana use over the period indicated by the year of birth of the survey participants after the impacts of age, period and other covariates are adjusted. Results in the figure show three distinctive cohorts with different risk patterns of current marijuana use during 1954–2003: (1) the Historical Declining Cohort (HDC): those born in 1954–1972, and characterized by a gradual and linear declining trend with some fluctuations; (2) the Sudden Increase Cohort (SIC): those born from 1972 to 1984, characterized with a rapid almost linear increasing trend; and (3) the Contemporary Declining Cohort (CDC): those born during 1984 and 2003, and characterized with a progressive declining over time. The detailed results of HAPC modeling analysis were also shown in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Fig. 4.

Cohort effect for the risk of marijuana use among US adolescents and young adults born during 1954–2003, overall and by male/female, estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method. Cohort effect γk were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

Discussion

This study provides new data regarding the risk of marijuana use in youth in the US during 1954–2016. This is a period in the US history with substantial increases and declines in drug use, including marijuana; accompanied with many ups and downs in legal actions against drug use since the 1970s and progressive marijuana legalization at the state level from the later 1990s till today (see Additional file 1: Table S2). Findings of the study indicate four-phase period effect and three-phase cohort effect, corresponding to various historical events of marijuana laws, regulations and social movements.

Coincident relationship between the period effect and legal drug control

The period effect derived from the HAPC model provides a net effect of the impact of time on marijuana use after the impact of age and birth cohort were adjusted. Findings in this study indicate that there was a progressive decline in the period effect during 1979 and 1992. This trend was corresponding to a period with the strongest legal actions at the national level, the War on Drugs by President Nixon (1969–1974) President Reagan (1981–1989) [45], and President Bush (1989) [45],and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [5].

The estimated period effect shows an increasing trend in 1992–2001. During this period, President Clinton advocated for the use of treatment to replace incarceration (1992) [45], Surgeon General Elders proposed to study marijuana legalization (1993–1994) [8], President Clinton’s position of the need to re-examine the entire policy against people who use drugs, and decriminalization of marijuana (2000) [45] and the passage of MML in eight US states.

The estimated period effect shows a declining trend in 2001–2006. Important laws/regulations include the Student Drug Testing Program promoted by President Bush, and the broadened the public schools’ authority to test illegal drugs among students given by the US Supreme Court (2002) [46].

The estimated period effect increases in 2006–2016. This is the period when the proportion of the population covered by MML progressively increased. This relation was further proved by a positive correlation between the estimated period effect and the proportion of the population covered by MML. In addition, several other events occurred. For example, over 500 economists wrote an open letter to President Bush, Congress and Governors of the US and called for marijuana legalization (2005) [47], and President Obama ended the federal interference with the state MML, treated marijuana as public health issues, and avoided using the term of “War on Drugs” [45]. The study also indicates that the proportion of population covered by RML was positively associated with the period effect although not significant which may be due to the limited number of data points of RML. Future studies may follow up to investigate the relationship between RML and rate of marijuana use.

Coincident relationship between the cohort effect and legal drug control

Cohort effect is the risk of marijuana use associated with the specific year of birth. People born in different years are exposed to different laws, regulations in the past, therefore, the risk of marijuana use for people may differ when they enter adolescence and adulthood. Findings in this study indicate three distinctive cohorts: HDC (1954–1972), SIC (1972–1984) and CDC (1984–2003). During HDC, the overall level of marijuana use was declining. Various laws/regulations of drug use in general and marijuana in particular may explain the declining trend. First, multiple laws passed to regulate the marijuana and other substance use before and during this period remained in effect, for example, the Marijuana Tax Act (1937), the Boggs Act (1952), the Narcotics Control Act (1956) and the Controlled Substance Act (1970). Secondly, the formation of government departments focusing on drug use prevention and control may contribute to the cohort effect, such as the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (1968) [48]. People born during this period may be exposed to the macro environment with laws and regulations against marijuana, thus, they may be less likely to use marijuana.

Compared to people born before 1972, the cohort effect for participants born during 1972 and 1984 was in coincidence with the increased risk of using marijuana shown as SIC. This trend was accompanied by the state and federal movements for marijuana use, which may alter the social environment and public attitudes and beliefs from prohibitive to acceptive. For example, seven states passed laws to decriminalize the marijuana use and reduced the penalty for personal possession of small amount of marijuana in 1976 [7]. Four more states joined the movement in two subsequent years [7]. People born during this period may have experienced tolerated environment of marijuana, and they may become more acceptable of marijuana use, increasing their likelihood of using marijuana.

A declining cohort CDC appeared immediately after 1984 and extended to 2003. This declining cohort effect was corresponding to a number of laws, regulations and movements prohibiting drug use. Typical examples included the War on Drugs initiated by President Nixon (1980s), the expansion of the drug war by President Reagan (1980s), the highly-publicized anti-drug campaign “Just Say No” by First Lady Nancy Reagan (early 1980s) [45], and the Zero Tolerance Policies in mid-to-late 1980s [45], the Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [5], the nationally televised speech of War on Drugs declared by President Bush in 1989 and the escalated War on Drugs by President Clinton (1993–2001) [45]. Meanwhile many activities of the federal government and social groups may also influence the social environment of using marijuana. For example, the Federal government opposed to legalize the cultivation of industrial hemp, and Federal agents shut down marijuana sales club in San Francisco in 1998 [48]. Individuals born in these years grew up in an environment against marijuana use which may decrease their likelihood of using marijuana when they enter adolescence and young adulthood.

Conclusion

This study applied the age-period-cohort model to investigate the independent age, period and cohort effects, and indicated that the model derived trends in marijuana use among adolescents and young adults were coincident with the laws and regulations on marijuana use in the United States since the 1950s. With more states legalizing marijuana use in the United States, emphasizing responsible use would be essential to protect youth from using marijuana.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, study data were collected through a household survey, which is subject to underreporting. Second, no causal relationship can be warranted using cross-sectional data, and further studies are needed to verify the association between the specific laws/regulation and the risk of marijuana use. Third, data were available to measure single-year age up to age 21 and two-year age group up to 25, preventing researchers from examining the risk of marijuana use for participants in other ages. Lastly, data derived from NSDUH were nation-wide, and future studies are needed to analyze state-level data and investigate the between-state differences. Although a systematic review of all laws and regulations related to marijuana and other drugs is beyond the scope of this study, findings from our study provide new data from a historical perspective much needed for the current trend in marijuana legalization across the nation to get the benefit from marijuana while to protect vulnerable children and youth in the US. It provides an opportunity for stack-holders to make public decisions by reviewing the findings of this analysis together with the laws and regulations at the federal and state levels over a long period since the 1950s.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Estimated Age, Period, Cohort Effects for the Trend of Marijuana Use in Past Month among Adolescents and Emerging Adults Aged 12 to 25 Years, NSDUH, 1979-2016. Table S2. Laws at the federal and state levels related to marijuana use.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACASI

Audio computer-assisted self-interviews

- APC

Age-period-cohort modeling

- CAPI

Computer-assisted person interviews

- CCREM

Cross-classified random-effects model

- CDC

Contemporary Declining Cohort

- HAPC

Hierarchical age-period-cohort

- HDC

Historical Declining Cohort

- MML

Medical Marijuana Laws

- NHSDA

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse

- NSDUH

National Survey on Drug Use and Health

- RML

Recreational Marijuana Laws

- SIC

Sudden Increase Cohort

- US

The United States

Authors’ contributions

BY designed the study, collected the data, conducted the data analysis, drafted and reviewed the manuscript; XGC designed the study and reviewed the manuscript. XFC and HY reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data of the study are available from the designated repository (https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida. Data in the study were public available.

Consent for publication

All authors consented for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12889-020-8253-4.

References

- 1.CDC. Marijuana and Public Health. 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/marijuana/index.htm. Accessed 13 June 2018.

- 2.SAMHSA. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.htm

- 3.Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana: An Evidence Review and Research Agenda, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed]

- 4.Collins C. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):879. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1407928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belenko SR. Drugs and drug policy in America: a documentary history. Westport: Greenwood Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerber RJ. Legalizing marijuana: Drug policy reform and prohibition politics. Westport: Praeger; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Single Eric W. The Impact of Marijuana Decriminalization: An Update. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1989;10(4):456. doi: 10.2307/3342518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SFChronicle. Ex-surgeon general backed legalizing marijuana before it was cool [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.sfchronicle.com/business/article/Ex-surgeon-general-backed-legalizing-marijuana-6799348.php

- 9.PROCON. 31 Legal Medical Marijuana States and DC. 2018 [cited 2018 Oct 4]. Available from: https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=000881

- 10.Bifulco M, Pisanti S. Medicinal use of cannabis in Europe: the fact that more countries legalize the medicinal use of cannabis should not become an argument for unfettered and uncontrolled use. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(2):130–132. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Models for the legal supply of cannabis: recent developments (Perspectives on drugs). 2016. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/pods/legal-supply-of-cannabis. Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

- 12.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Cannabis policy: status and recent developments. 2017. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/topics/cannabis-policy_en#section2. Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

- 13.Hughes B, Matias J, Griffiths P. Inconsistencies in the assumptions linking punitive sanctions and use of cannabis and new psychoactive substances in Europe. Addiction. 2018;113(12):2155–2157. doi: 10.1111/add.14372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mark Anderson D., Hansen Benjamin, Rees Daniel I. Medical Marijuana Laws and Teen Marijuana Use. American Law and Economics Review. 2015;17(2):495–528. doi: 10.1093/aler/ahv002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age and Sex for the United States, States, and Puerto Rico Commonwealth: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016 2016 Population Estimates. 2017 [cited 2018 Mar 14]. Available from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

- 16.Chen X, Yu B, Lasopa S, Cottler LB. Current patterns of marijuana use initiation by age among US adolescents and emerging adults: implications for intervention. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(3):261–270. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2016.1165239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miech R, Koester S. Trends in U.S., past-year marijuana use from 1985 to 2009: an age-period-cohort analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg L. The influence of neuroscience on US supreme court decisions about adolescents’ criminal culpability. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(7):513–518. doi: 10.1038/nrn3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Fink DS, Greene E, Le A, Boustead AE, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2018;113(6):1003–1016. doi: 10.1111/add.14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasin DS, Wall M, Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the USA from 1991 to 2014: results from annual, repeated cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(7):601–608. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pacula RL, Chriqui JF, King J. Marijuana decriminalization: what does it mean in the United States? National Bureau of Economic Research; 2003.

- 22.Donnelly N, Hall W, Christie P. The effects of the Cannabis expiation notice system on the prevalence of cannabis use in South Australia: evidence from the National Drug Strategy Household Surveys 1985-95. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2000;19(3):265–269. doi: 10.1080/713659382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorman DM, Huber JC. Do medical cannabis laws encourage cannabis use? Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18(3):160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynne-Landsman SD, Livingston MD, Wagenaar AC. Effects of state medical marijuana laws on adolescent marijuana use. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1500–1506. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pacula RL, Powell D, Heaton P, Sevigny EL. Assessing the effects of medical marijuana laws on marijuana and alcohol use: the devil is in the details. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013.

- 26.Harper S, Strumpf EC, Kaufman JS. Do medical marijuana laws increase marijuana use? Replication study and extension. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stolzenberg L, D’Alessio SJ, Dariano D. The effect of medical cannabis laws on juvenile cannabis use. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;27:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang GS, Roosevelt G, Heard K. Pediatric marijuana exposures in a medical marijuana state. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(7):630–633. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wall MM, Poh E, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin DS. Adolescent marijuana use from 2002 to 2008: higher in states with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(9):714–716. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Yu B, Stanton B, Cook RL, Chen D-GD, Okafor C. Medical marijuana laws and marijuana use among U.S. adolescents: evidence from michigan youth risk behavior surveillance data. J Drug Educ. 2018;47237918803361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Chen X. Information diffusion in the evaluation of medical marijuana laws’ impact on risk perception and use. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(12):e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Xinguang, Yu Bin, Stanton Bonita, Cook Robert L., Chen Ding-Geng(Din), Okafor Chukwuemeka. Medical Marijuana Laws and Marijuana Use Among U.S. Adolescents: Evidence From Michigan Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Data. Journal of Drug Education. 2018;48(1-2):18–35. doi: 10.1177/0047237918803361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Land K. Age-Period-Cohort Analysis: New Models, Methods, and Empirical Applications. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2013.

- 34.Yu B, Chen X. Age and birth cohort-adjusted rates of suicide mortality among US male and female youths aged 10 to 19 years from 1999 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1911383. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akiba S. Epidemiological studies of Fukushima residents exposed to ionising radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant prefecture--a preliminary review of current plans. J Radiol Prot. 2012;32(1):1–10. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/32/1/1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y, Land KC. Age-period-cohort analysis of repeated cross-section surveys: fixed or random effects? Sociol Methods Res. 2008;36(3):297–326. doi: 10.1177/0049124106292360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Brien Robert. Age-Period-Cohort Models. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen X, Sun Y, Li Z, Yu B, Gao G, Wang P. Historical trends in suicide risk for the residents of mainland China: APC modeling of the archived national suicide mortality rates during 1987-2012. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;54(1):99–110. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1593-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y. Social inequalities in happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: an age-period-cohort analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 2008;73(2):204–226. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reither EN, Hauser RM, Yang Y. Do birth cohorts matter? Age-period-cohort analyses of the obesity epidemic in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(10):1439–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerr WC, Lui C, Ye Y. Trends and age, period and cohort effects for marijuana use prevalence in the 1984-2015 US National Alcohol Surveys. Addiction. 2018;113(3):473–481. doi: 10.1111/add.14031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson RA, Gerstein DR. Age, period, and cohort effects in marijuana and alcohol incidence: United States females and males, 1961-1990. Substance Use Misuse. 2000;35(6–8):925–948. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 NSDUH: Summary of National Findings, SAMHSA, CBHSQ. 2014 [cited 2018 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.htm

- 44.Bauer DJ, Hussong AM. Psychometric approaches for developing commensurate measures across independent studies: traditional and new models. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(2):101–125. doi: 10.1037/a0015583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drug Policy Alliance. A Brief History of the Drug War. 2018 [cited 2018 Sep 27]. Available from: http://www.drugpolicy.org/issues/brief-history-drug-war

- 46.NIDA. Drug testing in schools. 2017 [cited 2018 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/drug-testing/faq-drug-testing-in-schools

- 47.Wikipedia contributors. Legal history of cannabis in the United States. 2015. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Legal_history_of_cannabis_in_the_United_States&oldid=674767854. Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

- 48.NORML. Marijuana law reform timeline. 2015. Available from: http://norml.org/shop/item/marijuana-law-reform-timeline. Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Estimated Age, Period, Cohort Effects for the Trend of Marijuana Use in Past Month among Adolescents and Emerging Adults Aged 12 to 25 Years, NSDUH, 1979-2016. Table S2. Laws at the federal and state levels related to marijuana use.

Data Availability Statement

The data of the study are available from the designated repository (https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm).