Abstract

Aims.

To explore the role of psychiatric admission, diagnosis and reported unfair treatment in the relationship between ethnicity and mistrust of mental health services.

Methods.

The Mental Illness-Related Investigations on Discrimination (MIRIAD) study was a cross-sectional study of 202 individuals using secondary mental health services in South London. Two structural equation models were estimated, one using Admission (whether admitted to hospital for psychiatric treatment in the past 5 years) and one using involuntary admission to hospital in the past 5 years.

Results.

Increased mistrust was directly associated with the latent variable ‘unfair treatment by mental health services and staff’ and with Black or mixed ethnicity in both models. Those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum (as compared to depression and bipolar disorder) had a lower average score on the latent variable, suggesting that on average they reported less unfair treatment. We found evidence of increased reporting of unfair treatment by those who had an admission in the past 5 years, had experienced involuntary admission, and for people of Black of mixed Black and White ethnicity.

Conclusions.

Neither prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum nor rates of hospital admission explained the greater mistrust of mental health services found among people of Black and mixed Black and White ethnicity compared with White ethnicity. Rather, people of Black and mixed Black and white ethnicity may be more likely to experience unfair treatment, generating mistrust; furthermore, this group is more likely to express mistrust even after accounting for reporting of unfair treatment by mental health services and staff.

Key words: Discrimination, Ethnicity, Involuntary psychiatric admission, Mistrust

Introduction

People in Black ethnic groups are at greater risk of being involuntarily detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 in England, according to a meta-analysis of 19 studies published in 2007 (Singh et al. 2007). The possible reasons for this are debated and to a large extent lacking in evidence (Harrison, 2002; Singh et al. 2007). Controlling for higher rates of psychosis among Black groups reduces but does not eliminate this difference (Davies et al. 1996). Some have suggested that this is a form of racial discrimination, linked to the stereotype that Black men in particular are more likely to be violent (Littlewood & Lipsedge, 1997). Health professionals may also misdiagnose and under-recognise mental illness in people of Black ethnicity, resulting in lower referral rates to specialist services (Fernando, 1988) and higher rates of involuntary admission through emergency pathways. Among Black minority groups, a greater degree of mental illness stigma (Evans-Lacko et al. 2013) has been suggested to deter help seeking (Harrison et al. 1989). Finally, there is evidence of greater dissatisfaction with mental health services among younger Black Caribbean service users, which appears to increase with the number of admissions (Parkman et al. 1997). Greater dissatisfaction reflects a lower level of trust (Verhaeghe & Bracke, 2011), which may reduce willingness to be admitted to hospital informally, resulting in a higher proportion of involuntary hospitalisations. This suggests a vicious cycle between detention under the Mental Health Act and mistrust of mental health services (Keating & Robertson, 2004). However, it should not be assumed that use of the Mental Health Act per se leads to mistrust, as other associated factors such as diagnosis and the experience of hospital admission, may also play a role (Keating & Robertson, 2004). The aim of this study was therefore to explore the role of these factors in the relationship between ethnicity and mistrust of mental health services. We hypothesised that being of Black ethnicity would be related to mistrust through: (1) a pathway of admission to hospital and the experience of unfair treatment from mental health staff; and (2) diagnosis, as other research has indicated a relationship between psychotic illness and lower trust of mental health professionals (Verhaeghe & Bracke, 2011).

Methods

The Mental Illness-Related Investigations on Discrimination (MIRIAD) study was a cross-sectional study of 202 individuals using secondary mental health services in South London. Data were collected between September 2011 and October 2012.

Recruitment and sample

Inclusion criteria for participants were: aged at least 18 years; a clinical diagnosis of either Major Depression, Bipolar or Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (ICD-10 F32, F21 and F20-F29 respectively); self-defined Black, White or Mixed (either Black and/or White mixed) ethnicity; current treatment with a community mental health team; sufficiently fluent in English to provide informed consent; and sufficiently well for participation to not pose a risk to their or others’ health or safety. We did not include Asian ethnicities due to low prevalence numbers in the target area; further, as rates of use of the Mental Health Act are highest among Black groups in comparison to White groups, these groups were chosen for inclusion in the study.

Service user participants were recruited from fourteen generic (n = 12) or early intervention in psychosis (n = 2) community mental health teams. Clinicians in the teams were presented with lists of service user participants who met inclusion criteria and asked if the service user was sufficiently well to participate. If so, a letter was posted to the service user inviting them to contact the research team. A reminder flyer was sent to non-responders within one month.

Data collection

Research Assistants administered the interview to consenting service user participants usually over two sessions (range 1–4). The interview schedule collected demographic and clinical information and contained a battery of measures on stigma, discrimination and access to care for mental and physical health; those relevant to this paper are detailed below. Clinical data were also extracted from electronic patient records.

Measures

Mistrust was measured using a single item: ‘Generally you can trust mental health staff and services’ with four response options, strongly agree to strongly disagree, adapted from a measure previously in research on social capital (Lindstrom, 2008).

Lifetime experienced discrimination was assessed by a count of the number out of twelve major experiences of unfair treatment in domains such as employment, physical health care and mental health care, by adapting the Major Experiences of Discrimination Scale (Williams et al. 1997; Kessler et al. 1999). For each domain, participants indicated if discrimination was experienced and were asked to give their perceived main attribution and secondary attributions. Possible attributions included race/ethnicity, religion, gender, mental illness and appearance.

The Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC-12) (Thornicroft et al. 2009; Brohan et al. 2013) was used to measure experienced discrimination on the basis of having a diagnosis of a mental illness. The DISC-12 is interviewer-administered, and contains: 21 items on negative, mental health-related experiences of discrimination, covering 21 specific life areas including mental and physical health care. All responses are given on a four point scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘a lot’.

The Barriers to Care Evaluation (BACE) (Clement et al. 2012) was used to assess barriers to mental health care. It asks respondents if they have ever been stopped, delayed or discouraged from seeking or continuing to seek professional care for a mental health problem due to a comprehensive list of potential barriers, conceptually categorised as stigma-related, attitudinal and instrumental barriers. It includes an item on having had previous bad experiences with mental health staff.

Current psychiatric symptoms were measured using the 18-item version of the British Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Hafkenscheid, 1993) In this scale, the following symptoms are rated on a seven-point scale: somatic concern, anxiety, emotional withdrawal, conceptual disorganisation, guilt feelings, tension, mannerisms and posturing, grandiosity, depressive mood, hostility, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behaviours, motor retardation, uncooperativeness, unusual thought content, blunted affect, excitement and disorientation. The scale is very widely used and has been shown to be reliable and valid. It is an interview measure for use by clinicians or researchers.

Data analysis

We first explored predictors of missing data. A total of eight individuals had missing data on one or more variables; including two individuals with missing data on Mental Health Act admission within the past 5 years. Black or mixed ethnicity was found to be a predictor of missing data. Univariate comparisons by ethnicity were made for demographic and clinical characteristics, unfair treatment in mental health services and mistrust.

To estimate the relative effects of these variables we used structural equation modelling, which allowed multiple response variables (endogenous and exogenous) to be estimated simultaneously. The distal outcome is mistrust, ‘Generally you can trust mental health staff and services’, a four-category ordinal item dichotomised into agree/disagree for a more parsimonious model with the small sample (n = 202).

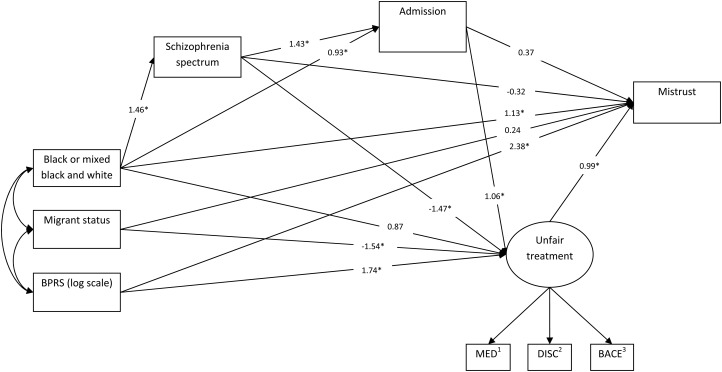

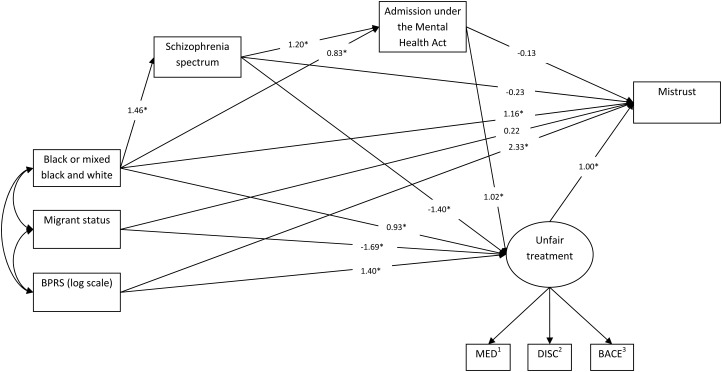

Two models were created, Model 1 using Admission (whether or not having ever had an admission to hospital for psychiatric treatment in the past 5 years, see Fig. 1) and Model 2 using involuntary admission to hospital (admission under the Mental Health Act in the past 5 years, see Fig. 2) as manifest variables.

Fig. 1.

Model (1) Significant association (p < 0.05). (1) ‘Have you ever been treated unfairly when getting or having mental health care?’ (MED, for which any attribution for the unfair treatment can be given). (2) ‘Have you been treated unfairly by mental health staff?’ (DISC, for the attribution of unfair treatment to having a psychiatric diagnosis). (3) ‘Having had previous bad experiences with mental health staff’.

Fig. 2.

Model (2) * Significant association (p < 0.05). (1) ‘Have you ever been treated unfairly when getting or having mental health care?’ (MED, for which any attribution for the unfair treatment can be given). (2) ‘Have you been treated unfairly by mental health staff?’ (DISC, for the attribution of unfair treatment to having a psychiatric diagnosis). (3) ‘Having had previous bad experiences with mental health staff’.

To define the experience of ‘unfair treatment by mental health services and staff’, a latent variable approach was used as multiple indicators of the unfair treatment were collected from the sample, and measurement error in these items could be more efficiently accounted for by using all indicators in this manner. Three relevant items, one from each of the MED, DISC and BACE were used to represent unfair treatment by mental health staff or services. These were: ‘Have you ever been treated unfairly when getting or having mental health care?’ (MED, for which any attribution for the unfair treatment can be given); ‘Have you been treated unfairly by mental health staff?’ (DISC, for the attribution of unfair treatment to having a psychiatric diagnosis); and ‘Having had previous bad experiences with mental health staff’ (BACE).

Other variables included in both models were: ethnic group (White or Other), migrant status (migrated to the UK v. born in the UK), Diagnosis (Schizophrenia v. Bipolar/Depression) and symptom severity (BPRS). See Figs 1 and 2 for more details.

Analyses were conducted in Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013). The models were estimated using participants with no missing data on independent variables (n = 197). The estimator used in the analysis was robust maximum likelihood (MLR), with 50 random sets of starting values and computing results on the ten best solutions. Maximum likelihood was chosen as an efficient estimator appropriate for structural equation modelling with continuous and categorical outcomes (Yuan & Bentler, 2000) that uses all information under missing at random assumptions (Rubin, 1976) for missing data in the outcomes, as well as covariates. Although missingness in the sample was small (4%), it was found that Black or mixed ethnicity was associated with missing outcome data. The models were also estimated using robust weighted least squares (mean and variance adjusted, rWLS) and produced similar results with the same interpretations. MLR was chosen to estimate the more conservative Huber–White s.e. that are robust to non-normality. Monte Carlo integration was required to fit the model involving admission under the Mental Health Act due to two observations with missing data for this variable. Models were assessed by various fit indices, which are reported to aid interpretation.

Results

4233 service users were screened for eligibility. 1345 (31.7%) were eligible and were invited to participate. 207 (15.4%) service users provided written and informed consent. There were no differences between eligible consenting and eligible non-consenting service users in terms of diagnoses, age, gender and ethnicity. Five service users were excluded after interview due to incorrect diagnoses (n = 4) or incomplete data (n = 1), leaving 202 participants.

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical variables by ethnicity with univariate analyses. The proportions of hospitalisation were different for the Black or mixed group compared to the White group, both for admission (83 v. 57%, p < 0.001) and admission under the Mental Health Act (26 v. 13%, p < 0.026). The Black or mixed group also reported higher mistrust in mental health services and Staff (34 v. 15%, p = 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical variables by ethnicity

| Non-Black or mixed ethnic Group | Black or mixed ethnic Group | Univariable Association* of Black or mixed ethnic group on outcome variables (p value) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean[s.d.]) | 43.2 | 11.9 | 40.3 | 9.8 | 0.059 |

| Gender (n[%]) | |||||

| Male | 54 | 50% | 38 | 40% | 0.173 |

| Female | 54 | 50% | 56 | 60% | |

| Diagnosis (n[%]) | |||||

| Bipolar | 28 | 26% | 13 | 14% | |

| Depression | 46 | 43% | 19 | 20% | |

| Schizophrenia spectrum | 34 | 31% | 62 | 66% | <0.001 |

| BPRS | 34.9 | 9.9 | 36.3 | 12.6 | 0.651 |

| Migration status (n[%]) | |||||

| Born in UK | 95 | 88% | 59 | 63% | |

| Migrated to UK | 13 | 12% | 35 | 37% | 0.001 |

| MED: ‘Have you ever been treated unfairly when getting or having mental health care?’ (n[%]) | |||||

| No | 63 | 58% | 51 | 54% | |

| Yes | 45 | 42% | 43 | 46% | 0.560 |

| DISC: ‘Have you been treated unfairly by mental health staff?’ (n[%]) | |||||

| No | 81 | 75% | 62 | 66% | |

| Yes | 27 | 25% | 32 | 32% | 0.159 |

| BACE: ‘Having had previous bad experiences with mental health staff’ (n[%]) | |||||

| No | 58 | 54% | 44 | 49% | |

| Yes | 50 | 46% | 46 | 51% | 0.500 |

| Mistrust in mental health staff and services (n[%]) | |||||

| No | 92 | 85% | 61 | 66% | |

| Yes | 16 | 15% | 32 | 34% | 0.001 |

| Hospital admission in last 60 months (n[%]) | |||||

| No | 46 | 43% | 16 | 17% | |

| Yes | 62 | 57% | 78 | 83% | <0.001 |

| Number of hospital admissions in last 60 months (median[IQR]) | |||||

| 2 | 1–6 | 3 | 2–4 | 0.846 | |

| Mental Health Act admission in last 60 months (n[%]) | |||||

| No | 93 | 87% | 67 | 74% | |

| Yes | 14 | 13% | 23 | 26% | 0.026 |

Pearson's chi-square test on all categorical, T-tests were used to test for differences in age and BPRS (log scale) and Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to test for differences in the number of admissions.

Results of the two structural equation models are presented in Table 2, and pathways with the fitted estimates can be found in Figs 1 and 2, respectively. Paths between migrant status and BPRS with diagnosis of schizophrenia and admission were tested and removed based on non-significance and modification indices. Negative pathways imply reduction while positive pathways imply an increase in the value of the variable, and those where evidence of a statistically significant association was found (p < 0.05) are marked with an asterisk. Both models fit the data well as assessed by the model fit indices (Model chi-square, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis index (TFI) and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA)).

Table 2.

Structural Equation Model results for the two models: Admission and Admission under the Mental Health Act

| MODEL (1) Admission | MODEL (2) Admission under the Mental Health Act | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate* (s.e.) | p value | Estimate* (s.e.) | p value | |

| Measurement | ||||

| Unfair Treatment by | ||||

| MED item | 1.000c | / | 1.000c | / |

| DISC item | 1.193 (0.450) | 0.008† | 1.180 (0.426) | 0.006† |

| BACE item | 0.801 (0.237) | 0.003† | 0.783 (0.256) | 0.002† |

| Structural | ||||

| Mistrust on | ||||

| Unfair Treatment | 0.994 (0.443) | 0.025† | 0.997 (0.427) | 0.020† |

| Admission(1) Mental Health Act Admission(2) | 0.369 (0.670) | 0.582 | −0.126 (0.709) | 0.859 |

| Log(BPRS) | 2.384 (0.922) | 0.010† | 2.328 (0.952) | 0.014† |

| Diagnosis: Schizophrenia | −0.321 (0.632) | 0.611 | −0.225 (0.662) | 0.734 |

| Black or mixed black and white ethnicity group | 1.134 (0.576) | 0.049† | 1.162 (0.573) | 0.043† |

| Migrant | 0.239 (0.700) | 0.733 | 0.222 (0.722) | 0.758 |

| Unfair Treatment on | ||||

| Admission(1) Mental Health Act Admission(2) | 1.064 (0.509) | 0.037† | 1.017 (0.490) | 0.038† |

| Log(BPRS) | 1.735 (0.716) | 0.015† | 1.900 (0.707) | 0.007† |

| Diagnosis: Schizophrenia | −1.465 (0.518) | 0.005† | −1.400 (0.508) | 0.006† |

| Black or mixed black and white ethnicity | 0.872 (0.453) | 0.054 | 0.929 (0.444) | 0.037† |

| Migrant | −1.537 (0.538) | 0.004† | −1.690 (0.554) | 0.002† |

| Admission(1) Mental Health Act Admission(2) on | ||||

| Diagnosis: Schizophrenia | 1.431 (0.376) | <0.001† | 1.203 (0.415) | 0.004† |

| Black or Mixed Ethnic group | 0.934 (0.369) | 0.011 | 0.830 (0.399) | 0.037 |

| Diagnosis: Schizophrenia on | ||||

| Black or Mixed Ethnic group | 1.457 (0.305) | <0.001† | 1.457 (0.305) | <0.001† |

| Model Fit: | ||||

| N | 197 | 197 | ||

| MODEL χ2 | χ2(16) = 18.234, p = 0.310 | χ2(16) = 20.033, p = 0.219 | ||

| CFI | 0.992 | 0.985 | ||

| TFL | 0.983 | 0.969 | ||

| RMSEA (90% CI) | 0.027 (0.000 to 0.073) | 0.036 (0.000 to 0.079 | ||

BY, measured by; ON, regressed on; CFI, comparative fit index; TFL, Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation; c, constrained; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.

*Estimates are in the form of logits except for the linear regression on the continuous latent variable ‘unfair treatment’ where regression coefficients are presented.

†Significant in rWLS estimated model.

Increased mistrust was directly associated with the latent variable ‘unfair treatment by mental health services and staff’ and with Black or mixed ethnicity in both models. No evidence was found for a direct association between increased mistrust and admission or a diagnosis of schizophrenia in either of the two models.

BPRS score was positively associated with both mistrust and unfair treatment in both models. However, those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum (as compared to depression and bipolar disorder) had a lower average score on the latent variable ‘unfair treatment by mental health services and staff’, suggesting that on average they reported less unfair treatment. This was significant in both models, and independent of the effects of admission and Black or mixed ethnic group. The Models showed evidence of increased unfair treatment for those who had an admission in the past 5 years and with admission under the Mental Health Act. There was also a trend for reporting increased unfair treatment in the Black or mixed ethnic group, with this trend reaching statistical significance in Model 2. On the other hand, migrants were less likely to report unfair treatment in both models.

Those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder had an increased likelihood of both admission (Model 1) and admission under the Mental Health Act (Model 2) adjusted for Black or mixed ethnic group. Black or mixed ethnic group was found to be associated with increased likelihood of an admission (Model 1) (p = 0.011) and for admission under the Mental Health Act (Model 2) (p = 0.037), although using the rWLS estimator they did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.067 and 0.201, respectively).

Discussion

Greater mistrust of mental health services was found among people of Black and mixed Black and white ethnicity compared with white ethnicity and this was not explained by the higher prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum in these groups, by their BPRS score nor by their greater rates of admission. While a diagnosis of schizophrenia as opposed to depression or bipolar disorder might be expected to lead to more reports of unfair treatment because of the greater rates of persecutory beliefs in this group, we thus found the opposite, and no direct association between schizophrenia and mistrust. Thus, reporting of unfair treatment and mistrust of services appear similar to complaints about care, which are rarely made on the basis of psychotic symptoms (Pitarka-Carcani et al. 2000). One possible explanation is that cognitive problems or negative symptoms due to schizophrenia lead to under-reporting of unfair treatment, but we were not able to explore this hypothesis in the current study. Given the negative association between schizophrenia and reporting unfair treatment and the lack of association with mistrust, it is interesting that BPRS score was positively associated with both of these variables. One possibility is that greater symptom severity increases service users’ exposure to the risk of unfair treatment by virtue of increased levels of contact with professionals.

Our results are partially consistent with previous work in that we found some evidence of an association between ethnicity and both admission and use of the Mental Health Act were after controlling for the higher prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum in Black and mixed Black and White ethnic groups (Singh et al. 2007).

These findings suggest that it is not necessarily use of the Mental Health Act nor even hospital admission itself which leads to subsequent mistrust of services among people of Black and mixed Black and White ethnicity. Rather, this group is more likely to express mistrust regardless of admission. There are several possible reasons for the latter finding, including greater experience of unfair treatment, for which we found some evidence; mistrust of health care based on personal experiences of racial discrimination (Armstrong et al. 2013), and mistrust based on hearing about others’ bad experiences with mental health services.

Examination of examples of unfair treatment provided by participants was consistent with results of the two models, in that while admission increases the likelihood of reporting unfair treatment and there were many examples of unfair treatment given by study participants that occurred while the participant was an inpatient, none of these examples specified being ‘sectioned’ (involuntarily detained in hospital) under the Mental Health Act as unfair treatment. Rather, ‘unfair treatment’ most often related to interactional issues such as not feeling listened to (Rose et al. 2011).

This study is subject to several limitations and our analyses have been performed accordingly. The small sample size prevents us from drawing firm conclusions about some of the relationships, particularly for the model using admission under the Mental Health Act. The sample did not include other major ethnic groups present in the UK and the results cannot be applied to these groups. The use of one item to assess trust in mental health services has not been validated but is widely used in studies of, e.g. trust in health care (Ahnquist et al. 2010); we did not find a brief validated measure. The cross-sectional design allows us to estimate the effects of historical events such as having had a psychiatric admission on current views such as mistrust, but critically we cannot determine the impact of mistrust and unfair treatment on subsequent clinical and service use outcomes. This represents important future work.

We hope that this exploratory study will lead to renewed efforts to design and test interventions to reduce both the ethnic disparities in inpatient service use reported elsewhere (Wilson, 2009) and the rates of unfair treatment within mental health services reported by service users (Corker et al. 2013), and to increase trust (Afuwape et al. 2010; Bhugra et al. 2011). Economic evaluation of the CRIMSON trial of joint crisis plans (Barrett et al. 2013) suggests that they are cost-effective for Black service users due to reduced inpatient service use. Furthermore, the use of advance statements can improve the therapeutic alliance with outpatient professionals (Swanson et al. 2006; Thornicroft et al. 2010). Future research should test whether the use of such advance statements can also reduce experiences of unfair treatment for any or all ethnic groups.

Financial Support

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Scheme (RP-PG-0606-1053). GT is also funded through a NIHR Specialist Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at the King's College London Institute of Psychiatry and the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standard

The study was approved by the East of England/Essex 2 Research Ethics Committee (ref. 11/EE/0052).

Contributor Information

Collaborators: the MIRIAD study group

References

- Afuwape SA, Craig TK, Harris T, Clarke M, Flood A, Olajide D, Cole E, Leese M, McCrone P, Thornicroft G (2010). The Cares of Life Project (CoLP): an exploratory randomised controlled trial of a community-based intervention for Black people with common mental disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 127, 370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahnquist J, Wamala SP, Lindstrom M (2010). What has trust in the health-care system got to do with psychological distress? Analyses from the national Swedish survey of public health. International Journal of Quality in Health Care 22, 250–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K, Putt M, Halbert CH, Grande D, Schwartz JS, Liao K, Marcus N, Demeter MB, Shea JA (2013). Prior experiences of racial discrimination and racial differences in health care system distrust. Medical Care 51, 144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett B, Waheed W, Farrelly S, Birchwood M, Dunn G, Flach C, Henderson C, Leese M, Lester H, Marshall M, Rose D, Sutherby K, Szmukler G, Thornicroft G, Byford S (2013). Randomised controlled trial of joint crisis plans to reduce compulsory treatment for people with psychosis: economic outcomes. Plos ONE DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074210 Nov 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D, Ayonrinde O, Butler G, Leese M, Thornicroft G (2011). A randomised controlled trial of assertive outreach vs. treatment as usual for Black people with severe mental illness. Epidemiological and Psychiatric Sciences 20, 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, Rose D, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G (2013). Development and psychometric validation of the Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC). Psychiatry Research 208, 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S, Brohan E, Jeffery D, Henderson C, Hatch SL, Thornicroft G (2012). Development and psychometric properties the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation scale (BACE) related to people with mental ill health. BMC Psychiatry 12, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corker E, Hamilton S, Henderson C, Weeks C, Pinfold V, Rose D, Wiliams P, Flach C, Gill V, Thornicroft G (2013). Experiences of discrimination among people using mental health service users in England 2008–11. British Journal of Psychiatry 202, s58–s63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S, Thornicroft G, Leese M, Higgingbotham A, Phelan M (1996). Ethnic differences in risk of compulsory psychiatric admission among representative cases of psychosis in London. British Medical Journal 312, 533–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko S, Henderson C, Thornicroft G (2013). Public knowledge, attitudes and behaviour regarding people with mental illness in England 2009–2012. British Journal of Psychiatry 202, s51–s57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando S (1988). Race and Culture in Psychiatry. Tavistock: London. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison G (2002). Ethnic minorities and the Mental Health Act. British Journal of Psychiatry 180, 198–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison G, Holton A, Neilson D, Owens D, Boot D, Cooper J (1989). Severe mental disorder in Afro-Caribbean patients: some social, demographic and service factors. Psychological Medicine 19, 683–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafkenscheid A (1993). Reliability of a standardized and expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: a replication study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 88, 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating F, Robertson D (2004). Fear, Black people and mental illness. A vicious circle? Health and Social Care in the Community 12, 439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 40, 208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom M (2008). Social capital, anticipated ethnic discrimination and self-reported psychological health: a population-based study. Social Science & Medicine 66, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlewood R, Lipsedge M (1997). Aliens and Alienists: Ethnic Minorities and Psychiatry. Routledge: London. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2013). Mplus User's Guide, 7th edn. Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Parkman S, Davies S, Leese M, Phelan M, Thornicroft G (1997). Ethnic differences in satisfaction with mental health services among representative people with psychosis in South London: PRiSM study 4. British Journal of Psychiatry 171, 260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitarka-Carcani I, Szmukler G, Henderson C (2000). Complaints about care in a mental health trust. Psychiatric Bulletin 24, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Rose D, Willis R, Brohan E, Sartorius N, Villares C, Wahlbeck K, Thornicroft G (2011). Reported stigma and discrimination by people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 20, 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin D (1976). Inference and missing data. Biometrika 63, 581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Greenwood N, White S, Churchill R (2007). Ethnicity and the Mental Health Act 1983. British Journal of Psychiatry 191, 99–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, Van Dorn R, Ferron J, Wagner HR, McCauley BJ, Kim M (2006). Facilitated psychiatric advance directives: a randomized trial of an intervention to foster advance treatment planning among persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 163, 1943–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N, Leese M (2009). Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 373, 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G, Farrelly S, Szmukler G, Birchwood M, Waheed W, Fiach C, Barett B, Byford S, Henderson C, Sutherby K, Lester H, Rose D, Dunn G, Leese M, Marshall M (2013). Randomised controlled trial of joint crisis plans to reduce compulsory treatment for people with psychosis: clinical outcomes. Lancet 381, 1634–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe M, Bracke P (2011). Stigma and trust among mental health service users. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 25, 294–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology 2, 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M (2009). Delivering Race Equality in Mental Health Care: a Review. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K, Bentler P (2000). Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data In Sociological Methodology 2000 (ed. Sobel ME and Becker MP), pp. 165–200. ASA: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]