Abstract

Background:

There are only a small number of prospective studies that have systematically evaluated standardised diagnostic criteria for mental disorder for more than a decade. The aim of this study is to present the approximated overall and sex-specific cumulative incidence of mental disorder in the Zurich cohort study, a prospective cohort study of 18–19 years olds from the canton of Zurich, Switzerland, who were followed through age 50.

Method:

A stratified sample of 591 participants were interviewed with the Structured Psychopathological Interview and Rating of the Social Consequences of Psychological Disturbances for Epidemiology, a semi-structured interview that uses a bottom-up approach to assess the past-year presence of 15 psychiatric syndromes. Seven interview waves took place between 1979 and 2008. Approximated cumulative incidence was estimated using Kaplan–Meier methods.

Results:

Rates of mental disorder were considerably higher than those generally reported in cross-sectional surveys. We found rates ranging from 32.5% for major depressive disorder to 1.2% for Bipolar I disorder. The cumulative probability of experiencing any of the mental disorders assessed by age 50 was 73.9%, the highest reported to date. We also found that rates differed by sex for most disorders, with females generally reporting higher rates of mood, anxiety and phobic disorder, and males reporting higher rates of substance- and alcohol-related disorders.

Conclusions:

These findings confirm those of other long-term prospective studies that indicate the nearly universal nature of disturbances of emotion and behaviour across the life span. Greater community awareness of the normative nature of these experiences is warranted. An important area of future research is study long-term course and stability to determine who among those with such disturbances suffer from chronic disabling mental disorders. Such longitudinal studies may aid in directing services and intervention efforts where they are most needed.

Key words: Epidemiology, prevalence, prospective, psychiatric disorders

Introduction

There is now widespread information on the prevalence and disability associated with mental disorders worldwide. A recent mega-analysis of data from 187 countries demonstrated that mental and substance use disorders are the leading cause of years lost to disability of any other disorder including heart disease, cancer and respiratory conditions (Whiteford et al. 2013). However, the overwhelming majority of systematic studies on the magnitude of mental disorders have been cross-sectional (e.g., Kessler et al. 2007) and there is relatively limited information from prospective longitudinal studies that track the onset of these conditions over time.

Although several studies have followed samples of children and adolescents through early adulthood (Cohen et al. 1993, Lewinsohn et al. 1993, Wittchen et al. 1998, Fergusson & Horwood, 2001, Moffitt et al. 2010, Gonzalez et al. 2012, Copeland et al. 2013), there are a limited number of studies that have tracked representative population samples of adults. Aside from the two classic longitudinal studies in psychiatric epidemiology that combined data from clinical registries, primary care, mental health treatment settings with personal interviews, the Lundby Study in Sweden (Essen-Möller, 1956, Hagnell et al. 1994, Asselmann et al. 2014) and the Stirling County, Nova Scotia Study (Murphy et al. 2008), there are few studies that have followed community cohorts using structured diagnostic interviews to ascertain standardised diagnostic criteria for the full range of Axis I Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) for more than a decade. These studies, including the Zurich Cohort Study of 19–20-year-old adults from Zurich, Switzerland (Angst et al. 2005), the Upper Bavarian Longitudinal Community Study (Fichter et al. 2010), the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-up (Eaton et al. 1997, Eaton et al. 2007), the Dunedin, New Zealand Study with multiple follow-ups of a birth cohort that included structured diagnostic interviews from age 18 to 32, (Moffitt et al. 2010); the Early developmental stages of psychopathology (EDSP) study in Munich, Germany that has followed a sample of adolescents and adults for up to 10 years (Wittchen et al. 1998, Asselmann et al. 2014) and the 10-year follow-up of the National Comorbidity Survey (Kessler et al. 2009), have provided substantial information about the prevalence, course, stability, risk factors comorbidity and mortality associated with mental disorders across the life span.

This paper provides data on the frequency of occurrence of mental disorders from the latest follow-up of the Zurich Cohort Study, when the participants were 49–50 years old. A previous paper in this journal reported cumulative 12-month prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders from age 20/21 to 40/41, assessed prospectively from 1979 to 1999 by six interviews (Angst et al. 2005). The aim of this study is to present the approximated cumulative incidence of mental disorders up to age 50, using information from all seven interview waves, both overall and by sex.

Methods

Sampling and procedure

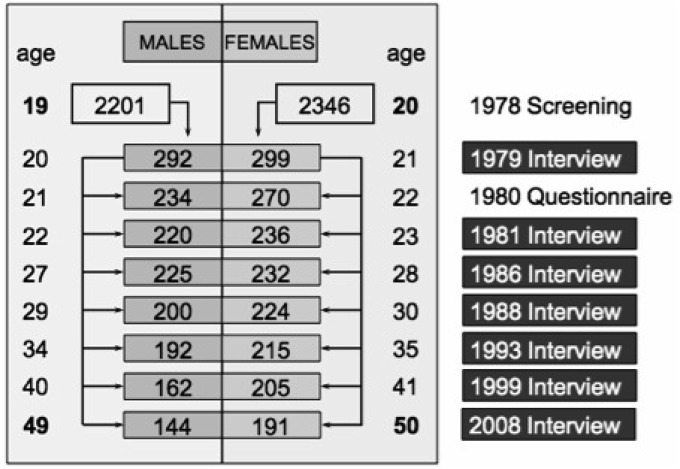

The Zurich Study comprised a cohort of 4547 subjects (2201 males; 2346 females) representative of the canton of Zurich in Switzerland, who were screened in 1978 with the Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) (Derogatis, 1977) when males were 19 and females 20 years old. Male and female participants were sampled with different approaches. In Switzerland, every male person must undertake a military screening test at the age of 19. Therefore, conscripts within a defined catchment area comprise its respective, complete male age group. With the consent of military authorities, but independent of their screening procedure, we randomly screened 50% of all male conscripts of the canton of Zurich of this age group. The refusal rate was 0.3%. Female participants were identified from the complete electoral register of the canton of Zurich. Again, 50% of them were randomly selected and received questionnaires by mail; 75% responded. In order to increase the probability of the development of psychiatric syndromes, a stratified subsample of 591 subjects (292 males, 299 females) was selected for interview, with two-thirds consisting of high scorers (defined by the 85th percentile or more of the global severity index (GSI) of the SCL-90-R) and a random sample of those with scores below the 85th percentile of the GSI. Such a two-phase procedure consisting of initial screening and subsequent interview with a stratified subsample is fairly common in epidemiological research (Dunn et al. 1999). Altogether seven interview waves have been conducted: in 1979, 1981, 1986, 1988, 1993, 1999 and in 2008 (see Fig. 1 for more information). The initial distribution above and below the 85th percentile of the GSI did not change over the seven interview waves, although dropouts were more common among extremely high or low scorers on the GSI (Eich et al. 2003). We repeated those dropout analyses for the last interview in 2008 and found additionally, that those participants who dropped out did not differ significantly in their socio-economic status and education at onset of the study from subjects who remained in the study. Neither was there a difference in initial psychopathologic impairment according to the nine SCL-90-R subscales. However, there were more dropouts among males (OR = 1.82; 95% CI = 1.31–2.53; p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Number and age of participants over seven assessment waves

Instrument and measures

Interviews were conducted with the ‘Structured Psychopathological Interview and Rating of the Social Consequences of Psychological Disturbances for Epidemiology’ (SPIKE) (Angst et al. 1984). This semi-structured interview, specifically developed for epidemiological surveys in psychiatric research, assesses data about socio-demography, somatic syndromes, psychopathology, substance use, medication, health services, impairment and social activity. Its reliability and validity have been reported previously (Angst et al. 2005). The SPIKE interview uses a bottom-up approach assessing the past-year presence of about 14 somatic and 15 psychiatric syndromes, checking symptoms, duration, frequency and recency of episodes, distress, impairment and treatment. The interviews administered by trained psychologists or psychiatrists focused mainly on the past year in order to minimise forgetting. As described in detail in the previous report, diagnoses were based on DSM-III, DSM-III-R and DSM-IV definitions (Angst et al. 2005). Exclusion criteria were not applied to any diagnoses in order to investigate associations between diagnostic categories.

The diagnoses were principally according to DSM criteria: 1986 by DSM-III, 1988 and 1993 by DSM-III-R and subsequently by DSM-IV. This was the case for major depressive disorders (MDD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD, panic), all phobias, bulimia and substance use disorders. Binge eating was defined by 4+ attacks over the past year. Anorexia was too rare to be considered. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) was always diagnosed according to DSM-III-R. Psychotic symptoms were assessed in the last interview; not a single case of schizophrenia was identified.

Statistical analysis

Cumulative incidence up to age 50 was approximated using information about past-year prevalence from seven interviews at ages 20–21, 22–23, 27–28, 29–30, 34–35, 40–41 and 49–50. The presence of past-year disorder at each wave was used as a proxy for disorder during the preceding interval (for the first interview, the start of the preceding interval is birth). Thus, the coverage of each interval was incomplete; episodes of disorder that arose after one interview wave and resolved before one year prior to the next wave were not captured. Our approximation therefore underestimates the true cumulative incidence at age 50.

Cumulative incidence was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier Product Limit method. Individuals were censored at the last follow-up wave in which they participated; for intervening waves with missing interviews, it was assumed that no new mental disorders arose. Cumulative incidence was calculated as the inverse of the proportion surviving without disorder at each wave. Confidence intervals were calculated using a log–log transformation. Analyses were weighted to adjust for the sample stratification and are therefore representative of the population cohort from which the sample was drawn. Analyses were conducted using the LIFETEST procedure of SAS version 9.3.

Results

Approximated cumulative incidence rates for various diagnoses at each assessment wave are displayed in Figs 2–5 and approximated cumulative incidence rates in 2008 (referred to as age 50) of mental disorders, by sex, are given in Table 1. Significant sex differences in cumulative incidence at age 50 are inferred on the basis of confidence interval overlap.

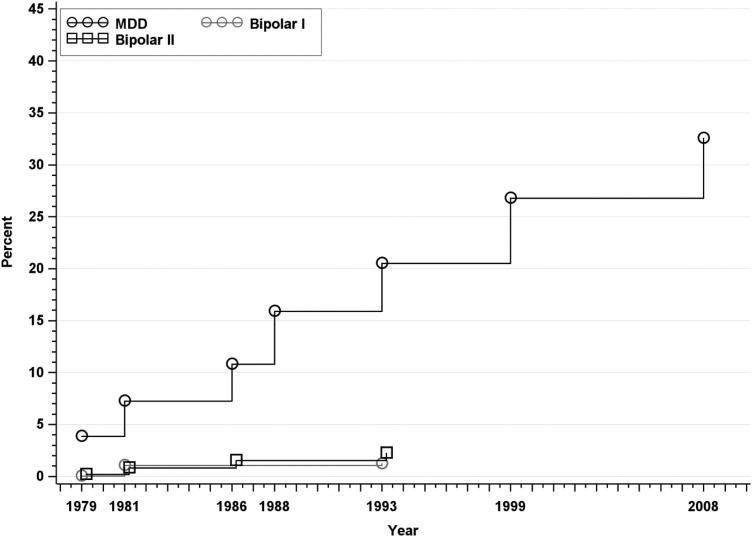

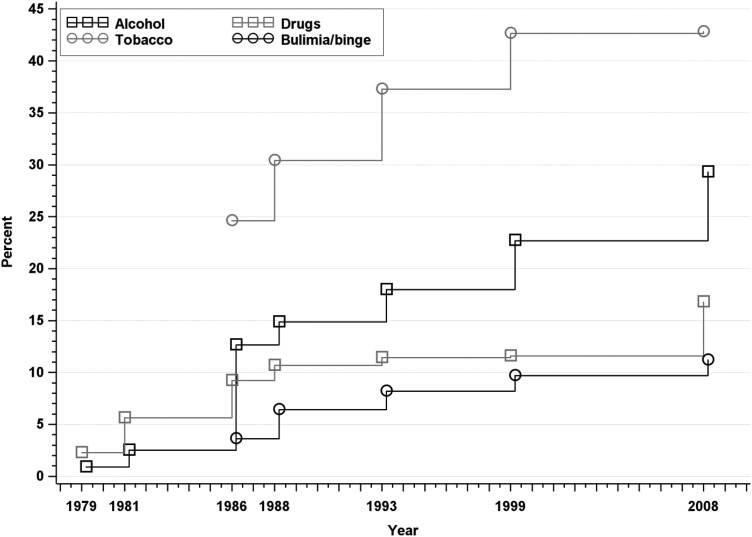

Fig. 2.

Approximated cumulative incidence to age 50 of MDD, Bipolar I disorder, and Bipolar II disorder in the Zurich Cohort Study, 1979–2008. Estimate in 1979 represents past-year prevalence; subsequent estimates incorporate new past-year cases at each wave.

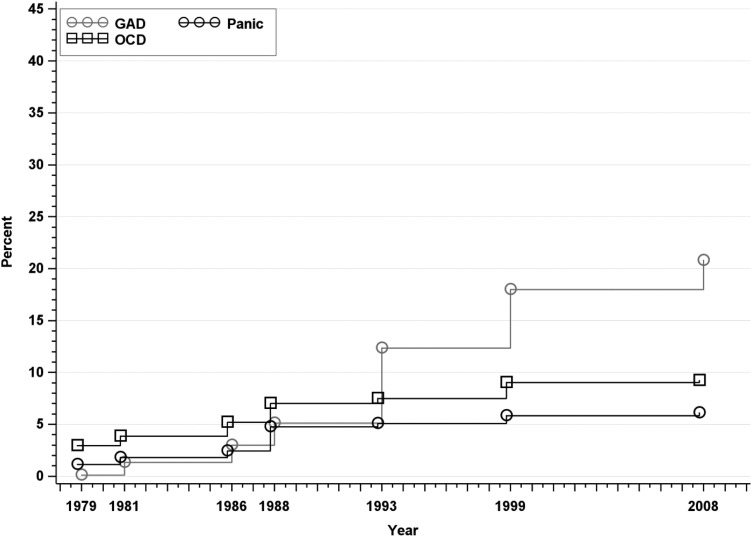

Fig. 3.

Approximated cumulative incidence to age 50 of Generalised Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder and Obsessive-compulsive Disorder in the Zurich Cohort Study, 1979–2008. Estimate in 1979 represents past-year prevalence; subsequent estimates incorporate new past-year cases at each wave.

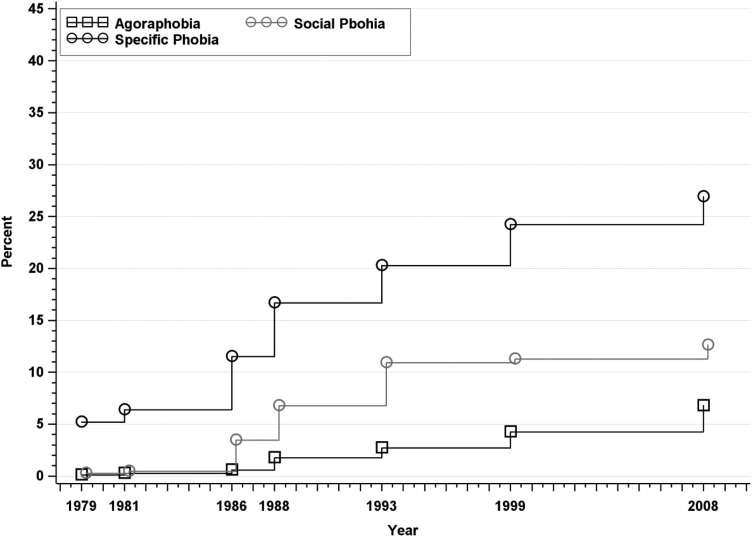

Fig. 4.

Approximated cumulative incidence to age 50 of phobias in the Zurich Cohort Study, 1979–2008. Estimate in 1979 represents past-year prevalence; subsequent estimates incorporate new past-year cases at each wave.

Fig. 5.

Approximated cumulative incidence to age 50 of alcohol abuse/dependence, drug abuse/dependence, tobacco dependence and bulimia/binge eating in the Zurich Cohort Study, 1979–2008. Estimate in 1979 represents past-year prevalence; subsequent estimates incorporate new past-year cases at each wave.

Table 1.

Approximated cumulative incidence of psychiatric disorders to age 50 in the Zurich Cohort Study

| Overall | Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disorder | CI | 95% CL | CI | 95% CL | CI | 95% CL |

| MDD | 32.54 | 30.44–34.75 | 25.23 | 22.46–28.28 | 39.33 | 36.31–42.51 |

| BPI | 1.21 | 0.83–1.75 | 0.11 | 0.02–0.76 | 2.25 | 1.54–3.28 |

| BPII | 2.22 | 1.68–2.95 | 1.93 | 1.24–3.01 | 2.51 | 1.74–3.60 |

| Agoraphobia | 6.79 | 5.69–8.08 | 2.46 | 1.57–3.86 | 10.72 | 8.88–12.90 |

| Social phobia | 12.61 | 11.21–14.18 | 10.69 | 8.82–12.92 | 14.66 | 12.63–16.99 |

| Specific phobia | 26.90 | 24.99–28.93 | 17.80 | 15.47–20.43 | 35.14 | 32.32–38.14 |

| Panic | 6.10 | 5.15–7.22 | 3.65 | 2.66–5.01 | 8.37 | 6.85–10.20 |

| GAD | 20.79 | 18.98–22.75 | 17.50 | 15.09–20.25 | 23.92 | 21.32–26.79 |

| OCD | 9.23 | 8.08–10.55 | 6.59 | 5.25–8.27 | 11.64 | 9.87–13.70 |

| Binge eating/bulimia | 11.21 | 9.86–12.72 | 5.55 | 4.16–7.38 | 16.87 | 14.68–19.34 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 29.30 | 27.27–31.44 | 44.26 | 41.01–47.65 | 15.21 | 13.05–17.70 |

| Alcohol abuse | 20.85 | 19.10–22.73 | 33.37 | 30.39–36.56 | 9.08 | 7.43–11.07 |

| Alcohol dependence | 17.72 | 15.99–19.61 | 27.30 | 24.39–30.48 | 8.77 | 7.07–10.86 |

| Drug use disorder | 16.78 | 15.18–18.54 | 20.50 | 18.00–23.29 | 13.39 | 11.41–15.67 |

| Sedatives | 9.51 | 8.22–10.99 | 9.89 | 7.98–12.22 | 9.31 | 7.63–11.32 |

| Stimulants | 4.05 | 3.31–4.96 | 6.55 | 5.24–8.17 | 1.59 | 0.99–2.53 |

| Opiates | 2.25 | 1.71–2.97 | 3.42 | 2.48–4.71 | 1.13 | 0.66–1.92 |

| Cannabis | 9.26 | 8.13–10.55 | 13.25 | 11.38–15.39 | 5.39 | 4.20–6.90 |

| Tobacco dependence | 42.83 | 40.68–45.04 | 48.45 | 45.32–51.67 | 37.49 | 34.59–40.54 |

CI, cumulative incidence; CL, confidence limits.

Rates of mood disorders are displayed in Fig. 2. The approximated cumulative incidence of MDD at age 50 was 32.54% (95% CI: 30.44–34.75) and was significantly higher in females than in males (39.33% v. 25.23%). There were no new cases of BPI or BPII after the 1993 assessment. The approximated cumulative incidence at age 50 was 1.21% for BPI (95% CI: 0.83–1.75) and 2.22% for BPII (95% CI: 1.68–2.95). Rates of BPI were higher in females than in males (2.25% v. 0.11%). Rates of BPII did not differ between males and females (Table 1).

The incidence rates of Panic, GAD and OCD are depicted in Fig. 3. Cumulative incidence of all three disorders at age 50 was higher in females compared with males (Table 1). There was no change in cumulative incidence of panic disorder from the previous interview. The overall cumulative incidence of panic disorder was 6.10% (95% CI: 5.15–7.22); 8.37% for females and 3.65% for males. The overall cumulative incidence of GAD was 20.79% (95% CI: 18.98–22.75); 23.92% for females and 17.50% for males. The cumulative incidence of OCD was 9.23% overall (95% CI: 8.08–10.55), 11.64% in females and 6.59% in males.

Incidence rates of phobias are displayed in Fig. 4. The cumulative incidence rates of all three phobias at age 50 were higher among females than males, but the male and female confidence intervals for social phobia barely overlapped. The cumulative incidence of agoraphobia was 6.79% overall (95% CI: 5.69–8.08), 10.72% among females and 2.46% among males. The cumulative incidence of social phobia was12.61% overall (95% CI: 11.21–14.18) and was slightly higher in females (14.66%) than males (10.69%), although confidence intervals overlapped slightly. The cumulative incidence of specific phobia was 26.90% overall (95% CI: 24.99–28.93) and was significantly higher in females (35.14%) than males (17.80%).

Incidence rates of substance use disorders are depicted in Fig. 5. All substance use disorders, with the exception of sedative abuse or dependence, were significantly more common among males than females, as was bulimia/binge eating. The cumulative incidence of any alcohol use disorder was 29.30% (95% CI: 27.27–31.44); 44.26% for males and 15.21% for females. The cumulative incidence of any drug use disorder was 16.78% (95% CI: 15.18–18.54); 20.50% among males and 13.39% among females. The most common drug use disorders were sedative abuse/dependence (9.51% overall, 95% CI: 8.22–10.99) and cannabis abuse/dependence (9.26% overall, 95% CI: 8.13–10.55), and the least common was opiate abuse/dependence (2.25% overall, 95% CI: 1.71–2.97). Tobacco dependence was the most common disorder assessed, with an overall cumulative incidence at age 50 of 42.83% (95% CI: 40.68–45.04); 48.45% among males and 37.49% among females. There was no change in cumulative incidence of tobacco dependence from the previous interview. The cumulative incidence of bulimia/binge eating at age 50 was 11.21% overall (95% CI: 9.86–12.72), 16.87% among females and 5.55% among males.

The cumulative incidence of any of the disorders considered at age 50 was 81.88% (95% CI: 80.04–83.65), and was similar between males (81.97%) and females (81.99%), with overlapping confidence intervals. When tobacco dependence was ignored, the cumulative incidence of any disorder at age 50 was 73.86% (95% CI: 71.78–75.89), and was also similar between males (72.30%) and females (75.41%) (not shown).

Discussion

Recent evidence indicates that rates of mental disorder estimated using prospectively-collected data are considerably higher than rates estimated via cross-sectional retrospective assessment (Moffitt et al. 2010, Copeland et al. 2011, Olino et al. 2012, Takayanagi et al. 2014). Here, using the data collected prospectively during seven waves of assessment over 29 years, we found corroborating evidence that rates of mental disorder up to age 50 are considerably higher than those generally reported in cross-sectional surveys (Kessler et al. 2007), with a range of rates of 1.2% for Bipolar I disorder to 32.5% for MDD. The cumulative probability of experiencing any of the mental disorders assessed by age 50 was 73.9%, the highest reported to date. We also found that rates differed by sex for most disorders, with females generally reporting higher rates of mood, anxiety and phobic disorder, and males reporting higher rates of substance- and alcohol-related disorders.

Cross-sectional surveys assessing lifetime prevalence have been shown to underestimate true lifetime risk (Andrews et al. 2005, Susser & Shrout, 2010). In the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication, the lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder among 49–59 years old was 46.5%, with markedly lower rates of nearly all individual disorders than those reported here, with the exception of panic disorder (Kessler et al. 2005). Among other Western European countries participating in the World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys, the lifetime prevalence of any mood disorder ranged from 9.9% in Germany and Italy to 21.0% in France, all substantially lower than our estimate of 32.5% for MDD alone (Kessler et al. 2007). The highest lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder observed in the WMH surveys outside of the USA was 39.3% in New Zealand, close to half the cumulative incidence at age 50 we observed here (Kessler et al. 2007).

Measures of disorder occurrence that rely upon retrospective recall are subject to forgetting (Andrews et al. 2005). A small number of longitudinal studies of mental disorder have compared rates generated from prospective assessment to those generated via retrospective recall (Moffitt et al. 2010, Copeland et al. 2011, Olino et al. 2012, Takayanagi et al. 2014). Moffitt et al. (2010) reported that when using data across four prospective waves from age 18 to 32 in the Dunedin Study, rates of disorder in some cases were almost double to those reported retrospectively in the New Zealand Mental Health Survey. The prospective assessment by Moffitt et al. that covered an age range that is similar to ages captured in the first five waves of the Zurich Cohort Study (20/21 to 34/35), yielded rates that are similar to or in excess of those reported here. Moffitt et al. (2010) found similar rates of panic (6.5%); higher rates of depression (41.4%), alcohol dependence (31.8%), cannabis dependence (18.0%) and social phobia (18.8%); and lower rates of specific phobia (18.8%) and GAD (14.2%). Likewise, using prospectively collected data over four interviews from age 16/17 to 34 in an adolescent cohort of youth from Oregon in the USA, Olino et al. (2012) reported the rates of panic disorder, alcohol use disorder and drug use disorder that were similar to those reported here; although rates of MDD were higher (47.1%) and rates of other disorders were lower. A recent study from the Baltimore Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study. Follow-up that compared prospectively – v. retrospectively – ascertained lifetime diagnoses of a range of mental and physical disorders found that retrospective estimates of mental disorders were 2–12 times lower than prospective estimates (Takayanagi et al. 2014). They reported comparable rates of panic disorder (6.7%) drug abuse or dependence (17.6%) alcohol abuse or dependence (25.9%) OCD (7.1%), and social phobia (25.3%) and lower rates of MDD (13.1%) than those reported herein. Although it is difficult to make strict comparisons between this study and others due to differences in methodology and in the age ranges considered (Copeland et al. 2011), it is informative that many of the rates we report here are of similar magnitude to those reported in the other long-term prospective studies mentioned above. This study adds to the growing body of evidence demonstrating that mental disorders are commonly experienced in the population (Copeland et al. 2011); a finding that may only be uncovered in prospective studies (Susser & Shrout, 2010).

We found sex differences in approximated cumulative incidence at age 50 for almost all of the disorders assessed. The only disorders for which we did not observe sex differences on the basis of confidence interval overlap were Bipolar II disorder, social phobia and sedative abuse or dependence. The pattern of sex differences was generally consistent with prior literature (Kessler et al. 2005, Seedat et al. 2009); females had higher rates of mood, anxiety, phobic and eating disorders, while males had higher rates of substance use disorders. Many of these differences were also mirrored in a recent national study of the cumulative incidence of treated disorders at age 50 in Denmark (Pedersen et al. 2014).

This study is the longest prospective follow-up study of a general population sample of adults to assess a variety of mental disorders. The ‘bottom-up’ approach of our diagnostic interview allowed us to systematically apply DSM-III, DSM-III-R and DSM-IV criteria as the study progressed to maintain comparability with other international studies of the epidemiology of mental disorders. Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample size, slight differences in the availability of diagnostic information across the study waves as the interview was adapted to changing diagnostic systems, and the high attrition rate that naturally occurs over such long periods of follow up. Our estimates assume that censoring in this study was non-informative. They also underestimate the true cumulative incidence to age 50 due to incomplete coverage of all observation years by the interview. The study was conducted among a particular birth cohort that may not generalise to other populations. Finally, slight methodological differences between this study and others hinder our ability to make strict comparisons between studies.

These findings have important implications both for public health as well as for mental health services and prevention. One important implication of these findings is that disturbances in emotion and behaviour at some point across mid-adulthood are nearly universal (Moffitt et al. 2010, Copeland et al. 2011). Education regarding the normative nature of periodic episodes of mood and anxiety disorders and potential remedies should be expanded to the community level, which may help reduce public stigma towards mental disorder (Pinfold et al. 2003, Hengartner et al. 2013). There is also a need for more prospective research on predictors of chronicity, severity and treatment of mental disorders across the lifespan. Knowledge regarding who are most likely to exhibit continuity of symptoms and impairment throughout early and middle adulthood will aid in directing services and intervention efforts where they are most needed (Merikangas, 2011).

Acknowledgement

None.

Financial Support

This work was supported by Grant numbers 3200-050881.97/1 and 32-50881.97 of the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The project received prior approval (1978) from the Ethical Committee of the Zurich University Psychiatric Hospital.

References

- Andrews G, Poulton R, Skoog I (2005). Lifetime risk of depression: restricted to a minority or waiting for most? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 495–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Dobler-Mikola A, Binder J (1984). The Zurich study – a prospective epidemiological study of depressive, neurotic and psychosomatic syndromes. European Archives of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 234, 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Gamma A, Neuenschwander M, Ajdacic-Gross V, Eich D, Rossler W, Merikangas KR (2005). Prevalence of mental disorders in the Zurich Cohort study: a twenty year prospective study. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 14, 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselmann E, Wittchen H-U, Lieb R, Höfler M, Beesdo-Baum K (2014). Associations of fearful spells and panic attacks with incident anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: a 10-year prospective-longitudinal community study of adolescents and young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 55, 8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J, Kasen S, Velez CN, Hartmark C, Johnson J, Rojas M, Brook J, Streuning E (1993). An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence—I. Age-and Gender-Specific Prevalence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34, 851–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland W, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A (2011). Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorders by young adulthood: a prospective cohort analysis from the great smoky mountains study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 252–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Adair CE, Smetanin P, Stiff D, Briante C, Colman I, Fergusson D, Horwood J, Poulton R, Costello EJ, Angold A (2013). Diagnostic transitions from childhood to adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 791–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR (1977). SCL-90: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual-I for the Revised Version and Other Instruments of the Psychopathology Rating Scale Series. John Hopkins University: Baltimore. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G, Pickles A, Tansella M, Vázquez-Barquero JL (1999). Two-phase epidemiological surveys in psychiatric research: editorial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton W, Kalaydjian A, Scharfstein D, Mezuk B, Ding Y (2007). Prevalence and incidence of depressive disorder: the Baltimore ECA follow-up, 1981–2004. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 116, 182–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Gallo J, Cai G, Tien A, Romanoski A, Lyketsos C, Chen L-S (1997). Natural history of Diagnostic Interview Schedule/DSM-IV major depression: the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eich D, Ajdacic-Gross V, Condrau M, Huber H, Gamma A, Angst J, Rössler W (2003). The Zurich Study: participation patterns and symptom checklist 90-R scores in six interviews, 1979–99. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108, 11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essen-Möller E, Larsson H, Uddenberg CE, White G (1956). Individual traits and morbidity in a Swedish rural population. Acta Psychiatricaet et Neurologica Scandinavica, (Suppl. 100), 1–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ (2001). The Christchurch health and development study: review of findings on child and adolescent mental health. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35, 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Fischer UC, Kohlboeck G (2010). Twenty-five-year course and outcome in anxiety and depression in the Upper Bavarian Longitudinal Community Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 122, 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Boyle MH, Kyu HH, Georgiades K, Duncan L, Macmillan HL (2012). Childhood and family influences on depression, chronic physical conditions, and their comorbidity: findings from the Ontario Child Health Study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46, 1475–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagnell O, Ojesjo L, Otterbeck L, Rorsman B (1994). Prevalence of mental disorders, personality traits and mental complaints in the Lundby Study. A point prevalence study of the 1957 Lundby cohort of 2,612 inhabitants of a geographically defined area who were re-examined in 1972 regardless of domicile. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine Supplementum, 50, 1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner M, Loch A, Lawson F, Guarniero F, Wang Y-P, Rössler W, Gattaz W (2013). Public stigmatization of different mental disorders: a comprehensive attitude survey. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 22, 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, De Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, De Girolamo G, Gluzman S, Gureje O, Haro JM (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry, 6, 168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Sampson N, Miller M, Nock MK (2009). The association between smoking and subsequent suicide-related outcomes in the National Comorbidity Survey panel sample. Molecular Psychiatry, 14, 1132–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA (1993). Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III – R disorders in high school students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR (2011). What is a case? New lessons from the great smoky mountains study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 213–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Kokaua J, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Poulton R (2010). How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychological Medicine, 40, 899–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Burke JD Jr., Monson RR, Horton NJ, Laird NM, Lesage A, Sobol AM, Leighton AH (2008). Mortality associated with depression. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43, 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Shankman SA, Klein DN, Seeley JR, Pettit JW, Farmer RF, Lewinsohn PM (2012). Lifetime rates of psychopathology in single versus multiple diagnostic assessments: comparison in a community sample of probands and siblings. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46, 1217–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB, Mors O, Bertelsen A, Waltoft BL, Agerbo E, McGrath JJ, Mortensen PB, Eaton WW (2014). A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 71, 573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinfold V, Toulmin H, Thornicroft G, Huxley P, Farmer P, Graham T (2003). Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: evaluation of educational interventions in UK secondary schools. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 182, 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedat S, Scott KM, Angermeyer MC, Berglund P, Bromet EJ, Brugha TS, Demyttenaere K, De Girolamo G, Haro JM, Jin R (2009). Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 785–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susser E, Shrout P (2010). Two plus two equals three? Do we need to rethink lifetime prevalence? Psychological Medicine, 40, 895–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi Y, Spira AP, Roth KB, Gallo JJ, Eaton WW, Mojtabai R (2014). Accuracy of reports of lifetime mental and physical disorders: results from the Baltimore epidemiological catchment area study. JAMA Psychiatry, 71, 273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Flaxman AD, Johns N (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 382, 1575–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H-U, Nelson CB, Lachner G (1998). Prevalence of mental disorders and psychosocial impairments in adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine, 28, 109–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]