Abstract

Aims.

Few studies have compared time trends for the incidence of psychosis. To date, the results have been inconsistent, showing a decline, an increase or no significant change. As far as we know, no studies explored changes in prevalence of early risk factors. The aim of this study was to investigate differences in early risk factors and cumulative incidences of psychosis by type of psychosis in two comparable birth cohorts.

Methods.

The Northern Finland Birth cohorts (NFBCs) 1966 (N = 12 058) and 1986 (N = 9432) are prospective general population-based cohorts with the children followed since mother's mid-pregnancy. The data for psychoses, i.e. schizophrenia (narrow, spectrum), bipolar disorder with psychotic features, major depressive episode with psychotic features, brief psychosis and other psychoses (ICD 8–10) were collected from nationwide registers including both inpatients and outpatients. The data on early risk factors including sex and place of birth of the offspring, parental age and psychosis, maternal education at birth were prospectively collected from the population registers. The follow-up reached until the age of 27 years.

Results.

An increase in the cumulative incidence of all psychoses was seen (1.01% in NFBC 1966 v. 1.90% in NFBC 1986; p < 0.001), which was due to an increase in diagnosed affective and other psychoses. Earlier onset of cases and relatively more psychoses in women were observed in the NFBC 1986. Changes in prevalence of potential early risk factors were identified, but only parental psychosis was a significant predictor in both cohorts (hazard ratios ≥3.0; 95% CI 1.86–4.88). The difference in psychosis incidence was not dependent on changes in prevalence of studied early risk factors.

Conclusions.

Surprisingly, increase in the cumulative incidence of psychosis and also changes in the types of psychoses were found between two birth cohorts 20 years apart. The observed differences could be due to real changes in incidence or they can be attributable to changes in diagnostic practices, or to early psychosis detection and treatment.

Key words: Cumulative incidence, early risk factors, psychosis, schizophrenia

Introduction

Time trends in the incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses have been challenging to investigate due to the lack of suitably large and comparable samples from different time periods. Other challenges include differences and changes in population structure, diagnostic criteria, risk factors, health care organisation, and biases in data recording (Kendell et al. 1993). Studies have not shown large difference in incidence rates across countries worldwide (Jablensky, 2000). In a systematic review of studies from 33 countries, the median value of the incidence of schizophrenia was 15.2 (7.7–43.0) per 100 000 (McGrath et al. 2004).

Results of previous incidence studies of psychosis over time in high-income countries since 1960s have been inconsistent, some reporting a decline (Takei et al. 1996; Brewin et al. 1997; Suvisaari et al. 1999; Ösby et al. 2001) increase (Häfner & an der Heiden 1986; Bamrah et al. 1991) or no change in incidence (Allardyce et al. 2000; Kirkbride et al. 2009). Studies from the Nottingham, England reported greater variety of psychotic diagnoses in cohort 1992–1994 compared with 1978–1980 (Brewin et al. 1997) and increase in other non-affective psychoses (away from schizophrenia) over three time periods (1978–1980, 1993–1995 and 1997–1999) (Kirkbride et al. 2009). A meta-analysis suggested the pooled annual incidence of all psychoses in England over the period 1950–2009 was 31.7 (95% CI 24.6–40.9) per 100 000 person-years and 15.2 (95% CI 11.9–19.5) for schizophrenia (Kirkbride et al. 2012). The results of these studies support that incidences of schizophrenia do not vary significantly, but estimates for all psychoses vary over time, indicating inconsistency between studies on time trends of schizophrenia (McGrath et al. 2004; Kirkbride et al. 2009).

In Finland the lifetime prevalence of any psychosis varies regionally from 2.2 to 4.6%, with the highest prevalence in Northern Finland. The differences have been explained by area-related environmental factors (e.g. more underweight newborns in rural Eastern and Northern regions) and genetic predisposition (Perälä et al. 2008). Suvisaari et al. (1999) identified a decline in the incidence of schizophrenia in Finland in the period 1954–1965 and Haukka et al. (2001) found that urban birth increased incidence in cohorts born since 1955.

In the beginning of the 1990s in Finland new Mental Health Act led to significant changes and resulted in integration of mental health with somatic health and social services, the decentralisation of the financing and the deinstitutionalisation process. A reduction of psychiatric beds in hospitals from 20 000 to 6000 during period of 20 years since 1980s was followed by development of out-patient care and community based mental health services. It has been claimed sometimes that outpatient care did not receive enough resources in that period. On the other hand, extra budget was allocated for the development of mental health services for young people (Lehtinen & Taipale, 2001). Furthermore, the diagnostic system of diseases in Finland has changed from ICD 8 (1968–1986) via ICD 9 (1987–1995) to ICD 10 (1996–2012).

Previous studies have identified a number of early risk factors for schizophrenia and psychosis such as male sex (Matheson et al. 2011), family history of schizophrenia (Gottesman, 1991) or other psychoses and severe mental disorders (Matheson et al. 2011), advanced paternal age (Miller et al. 2011), unwanted pregnancy (Myhrman et al. 1996) and maternal depression during pregnancy in offspring with parental psychosis (Mäki et al. 2010), obstetric complications (Matheson et al. 2011), low birth weight (Isohanni et al. 2006), infections in the central nervous system during childhood (Khandaker et al. 2014), stressful life events and childhood adversities (Varese et al. 2012), cannabis use later in life and urban residence (Matheson et al. 2014). A higher incidence of psychosis across the lifespan among males than females has been reported (Kleinhaus et al. 2011) and previous studies on gender differences in onset age focus primarily on schizophrenia rather than other psychoses (Gureje, 1991). Many risk factors are non-specific for schizophrenia and overlap with other psychotic and psychiatric disorders (Laursen et al. 2007), but this area requires further investigation (Laurens et al. 2015). Still, there seems to be lack of studies on consistency of early risk factors in the same geographical region over time.

Finland offers an ideal setting to explore time trends in the incidence of psychosis due to its high-quality health care registers, personal identity code use for each resident, a homogenous population, and a low migration rate (Miettunen, 2011). Furthermore, our data base, the two Northern Finland Birth Cohorts (NFBC 1966 and NFBC 1986) are unique, comparable and large general population cohorts based in the same geographical region with data collected prospectively since pregnancy.

The aim of the present study is to explore in two cohorts setup 20 years apart: (1) the cumulative incidence of psychoses and age of illness onset; (2) changes in type of diagnosis; and (3) changes in the early risk factors in order to be able to understand changes and determinants of the risk of psychosis over time.

Methods

Sample

The NFBC 1966 (N = 12 058) and 1986 (N = 9432) are prospective birth cohorts covering the two northernmost former provinces of Finland (i.e. Oulu and Lapland) with a population of 604 000 and 630 000 at their baseline data collection, respectively (Statistics Finland, 2015). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Identification of psychoses

The data for psychoses were collected from several registers:

-

(1)

Care Register for Health Care (CRHC);

-

(2)

Finnish outpatient registers;

-

(3)

Social Insurance Institution (SII) registers: reimbursable medicines, sick days, and disability pensions;

-

(4)

Finnish Centre for Pensions: disability pensions.

For more details on the registers and time periods see Supplementary material 1. We included data only up to the age 27 years in both cohorts for study subjects as this was the average age at the last follow-up in NFBC 1986. Parental psychosis was identified through disability pensions registers since 1964, CRHC since 1972, specialised outpatient care data since 1998 and primary care outpatient care data since 2011 (Miettunen, 2011) until children's age 27, except sick days and reimbursable medicines which were not available for parents.

Diagnostic criteria and age of illness onset

Psychoses were defined according to ICD 8 (1968–1986), ICD 9 (1987–1995) or ICD 10 (1996–2012). The diagnostic categories included are presented in Table 1. The diagnosis and age of onset were based on the first day of any psychosis treatment recorded in the registers. In case of disability pensions registers, the onset was defined as 1 year before the recorded date, since in Finland disability pension is allowed at the earliest 1 year after the onset of psychosis. The earliest age of onset was defined as a minimum 12 years old due to inconsistency in psychosis diagnosis in childhood (McKenna et al. 1994).

Table 1.

Diagnostic categories of psychotic disorder based on ICD 8–10

| Diagnosis | ICD-8 code (1968–1986) | ICD-9 code (1987–1995) | ICD-10 code (1996–2012) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | 295, 2954 | 295, 2954 | F20 |

| Schizophrenia spectrum | |||

| Schizoaffective disorder | 2957 | 2957 | F25 |

| Delusional disorder | 297 | 297 | F22 |

| Bipolar disorder (with psychotic features) | 2961–2969 | 2962E, 2963E, 2964E, 2967 | F302, F312, F315 |

| Major depressive disorder (with psychotic features) | 2960, 2980 | 2961E | F323, F333 |

| Brief psychosis | 298 (except 2980) | 2988 | F23, F24 |

| Other non-organic psychoses | 299 | 2989 | F28,F29 |

Early risk factors

We investigated some of the risk factors that were reported to be associated with psychosis in previous reviews, if the comparable data were available for both NFBCs.

The following variables were used as predictors of psychosis: sex, diagnosis of psychosis in parents before the participant was 27 years of age (yes/no), paternal age (<25, 25–40, >40 years), maternal age at delivery (<20, 20–35, >35 years), place of residence at birth (urban/rural) and maternal education at baseline (basic, secondary, higher education). Urban residence was classified as born in the six largest cities in the region (Statistics Finland, 2015). The categorical variables for parental age and maternal education were created based on the previous NFBC studies (Keskinen et al. 2013).

Data on birth dates (cohort members and their parents), sex and parental psychosis were obtained from the national registers (cf. above). At baseline (i.e. at birth), information on place of residence and maternal education was collected from parents’ questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables (sex, parental psychosis, maternal education, place of residence, maternal and paternal age) and student's t-test was used to compare the continuous variable (onset age of psychosis). Cox regression was applied in the univariate analyses to explore the relationships between the exposures and the outcome. We assumed that adjusting would not have given reliable estimates of hazard ratios (HRs) since most of the unadjusted HRs were non-significant and number of cases was relatively low. Association between changes in risk factors and incidence was studied with the pooled data (NFBCs 1966 and 1986) by cox regression with a cohort membership variable as a predictor and other risk factors as covariates in a multivariate analysis. Times of emigration and death were used as censoring points in analyses (information from the Population Register Centre). Cohort members with undefined outcome due to death and emigration before age of 12 (minimum age of onset) were excluded (n = 901 in NFBC 1966; n = 150 in NFBC 1986). Risk estimates were expressed as HRs with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Interactions between cohort membership and risk factors (cohort*risk factor) were also studied using Cox regression. Data analyses were carried out using SPSS Statistics version 21, International Business Machines (IBM).

Results

Cumulative incidence and age of onset of psychosis

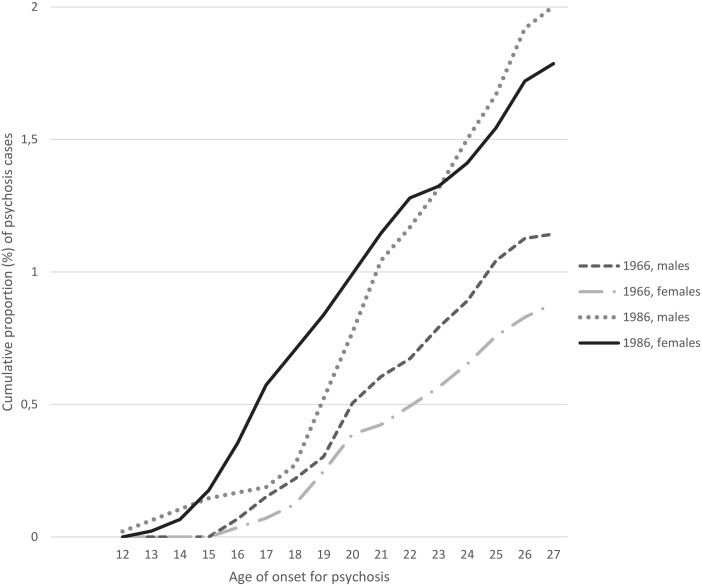

The cumulative incidence of psychosis was lower in the NFBC 1966 than in the NFBC 1986 (1.01 v. 1.90%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The mean, median and standard deviation (s.d.) of age of onset for psychosis did not differ between the total cohorts (p = 0.08) being 21.54, 21.45 (s.d.: 3.22) years in the NFBC 1966 and 20.94, 20.97 (s.d.: 3.76) years in the NFBC 1986, respectively. Among women, the NFBC 1986 had significantly earlier mean age of onset of psychosis than NFBC 1966 (i.e. 20.15 (3.88) v. 21.74 (3.36), p = 0.018). To investigate distinct trend (Fig. 1), men and women were compared until age of 18 years. Until that age women in the NFBC 1986 had a higher cumulative incidence of psychosis compared to men in the NFBC 1986 and women in the NFBC 1966 (p < 0.001). However, after age of 18 years the difference between males and females in NFBC 1986 was no longer significant (p = 0.166).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidences of psychoses among males and females in the NFBC 1966 and NFBC 1986.

Types of diagnosis

A shift in types of diagnosis between the two cohorts was found (Table 2). While the proportion of schizophrenia was quite similar (0.45/0.42%), more cases with schizophrenia spectrum, affective psychoses (bipolar disorder, major depression) and other psychoses (brief psychosis, other non-organic psychoses) were seen in the NFBC 1986. Among all psychotic cases, altogether 4% (n = 5) had bipolar disorder (psychotic) and 2% (n = 2) had major depression (psychotic) in the NFBC 1966, while the respective figures for NFBC 1986 were, 10% (n = 17) and 15% (n = 27) (in Table 2 the proportions are calculated by the total study sample).

Table 2.

Cumulative incidence (%) of different psychotic disorders in the cohorts by the age of 27 years

| NFBC 1966 (N = 11 621) | NFBC 1986 (N = 9329) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | n (%) | n (%) | p-value |

| Schizophrenia | 53 (0.45%) | 39 (0.42%) | 0.751 |

| Schizophrenia spectrum* | 8 (0.06%) | 11 (0.12%) | 0.257 |

| Bipolar disorder with psychotic features | 5 (0.04%) | 17 (0.18%) | 0.002 |

| Major depressive episode with psychotic features | 2 (0.02%) | 27 (0.29%) | p < 0.001 |

| Brief psychosis | 13 (0.11%) | 20 (0.21%) | 0.078 |

| Other non-organic psychoses | 37 (0.32%) | 63 (0.68%) | p < 0.001 |

| Total | 118 (1.01%) | 177 (1.90%) | p < 0.001 |

Note: schizophrenia spectrum includes schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder.

Early risk factors

Socio-demographic characteristics and distribution of early risk factors of psychosis differed between the two cohorts. The NFBC 1966 had more subjects with a parental psychosis (6.4 v. 4.6%), fewer subjects with urban residence (30.5 v. 43.3%) and with mothers having at least a secondary education (22.7 v. 67.2%) compared to NFBC 1986 (Table 3). In addition, higher proportions of parents were 20–35 years old and fewer were <20 years old in the NFBC 1986 compared to the NFBC 1966.

Table 3.

Distribution of early risk factors

| Predictor | NFBC 1966, n (%) | NFBC 1986, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | N = 11 621 | N = 9321 | p-value |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 5949 (51.2%) | 4794 (51.4%) | p = 0.778 |

| Female | 5672 (48.8%) | 4535 (48.6%) | |

| Parental psychosis (until age 27) | p < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 746 (6.4%) | 430 (4.6%) | |

| No | 10 875 (93.6%) | 8899 (95.4%) | |

| Mother's education at birth | |||

| Basic education (9 years) | 8361 (73.2%) | 2100 (26.5%) | p < 0.001 |

| Secondary education | 2591 (22.7%) | 5334 (67.2%) | |

| Higher education | 464 (4.1%) | 503 (6.3%) | |

| Place of residence at birth | |||

| Urban | 3547 (30.5%) | 3938 (43.3%) | p < 0.001 |

| Rural | 8074 (69.5%) | 5158 (56.7%) | |

| Maternal age at birth (years) | |||

| <20 | 1144 (9.9%) | 394 (4.2%) | p < 0.001 |

| 20–35 | 8431 (73.2%) | 7710 (82.6%) | |

| >35 | 1945 (16.9%) | 1225 (13.1%) | |

| Paternal age at birth (years) | |||

| <25 | 2405 (22.2%) | 1568 (17.0%) | p < 0.001 |

| 25–40 | 7092 (65.6%) | 7052 (76.4%) | |

| >40 | 1315 (12.2%) | 614 (6.6%) |

Only parental psychosis was found to be a predictor of psychosis in both cohorts with about a threefold risk increase: HR1966 = 3.01 (95% CI 1.86–4.88); HR1986 = 2.99 (95% CI 1.91–4.67) (Table 4). There was no evidence for an interaction between cohort membership and any of the studied risk factors (i.e. sex, parental psychosis, baseline mother's education, place of residence and parental age) in the causation of psychosis (data not shown).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis of early risk factors for psychosis in the cohorts presented in HR

| NFBC 1966 N = 11 621 |

NFBC 1986 N = 9321 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | n/N (%) | HR (95%CI) | n/N (%) | HR (95%CI) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 68/118 (57.6%) | 1.30 (0.90–1.87) | 96/177 (54.2%) | 1.12 (0.84–1.51) |

| Female | 50/118 (42.4%) | 1 | 81/177 (45.8%) | 1 |

| Parental psychosis (until age 27) | ||||

| No | 98/118 (83.1%) | 1 | 155/177 (87.6%) | 1 |

| Yes | 20/118 (16.9%) | 3.01 (1.86–4.88) | 22/177 (12.4%) | 2.99 (1.91–4.67) |

| Mother's education at birth | ||||

| Basic education | 80/117 (68.4%) | 0.77 (0.51–1.17) | 41/143 (28.7%) | 1.15 (0.79–1.66) |

| Secondary education | 32/117 (27.4%) | 1 | 91/143 (63.6%) | 1 |

| Higher education | 5/117 (4.3%) | 0.87 (0.34–2.23) | 11/143 (7.7%) | 1.29 (0.69–2.41) |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 38/118 (32.2%) | 1 | 82/171 (48.0%) | 1 |

| Rural | 80/118 (67.8%) | 1.08 (0.74–1.59) | 89/171 (52.0%) | 1.21 (0.90–1.64) |

| Maternal age | ||||

| <20 | 10/117 (8.5%) | 0.89 (0.46–1.72) | 9/177 (5.1%) | 1.23 (0.63–2.41) |

| 20–35 | 83/117 (70.9%) | 1 | 143/177 (80.8%) | 1 |

| >35 | 24/117 (20.5%) | 1.26 (0.80–1.98) | 25/177 (14.1%) | 1.01 (0.72–1.68) |

| Paternal age | ||||

| <25 | 19/112 (17.0%) | 0.69 (0.42–1.14) | 28/176 (15.9%) | 0.94 (0.62–1.41) |

| 25–40 | 81/112 (72.3%) | 1 | 134/176 (76.1%) | 1 |

| >40 | 12/113 (10.7%) | 0.80 (0.44–1.47) | 14/176 (8.0%) | 1.21 (0.70–2.10) |

HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

We explored association between changes in risk factors and incidence. The unadjusted HR for the cohort membership variable (NFBC 1986 v. NFBC 1966) in respect to incidence of psychosis was 1.88 (95% CI 1.49–2.38), that indicated that members of NFBC 1986 had higher risk to develop psychosis compared with NFBC 1966. After adjustments with parental psychosis, place of residence, paternal age and education, the HR was 1.73 (95% CI 1.35–2.23) (not shown in tables).

Sex differences in psychosis

The proportion of psychosis in men was significantly higher in the NFBC 1966 than in NFCB 1986, (p < 0.001). When only men with psychoses were compared between cohorts, the proportion of individuals with a secondary education was lower (p < 0.001) and rural residence was higher (p = 0.003) than in the NFBC 1966. In women with psychosis, only the proportion of individuals with a secondary education was lower in the NFBC 1966 (p < 0.001).

In NFBC 1986, the mean age of onset of psychosis was earlier in women than in men (20.15 years (s.d.: 3.88) v. 21.61 years (s.d.: 3.52); p = 0.01) (not shown in tables). Men had more schizophrenia (narrow) diagnoses (p = 0.013), (psychotic) major depression (p = 0.011) and other psychoses (p = 0.078) compared with men in the NFBC 1966. Also women in NFBC 1986 had more schizophrenia (p = 0.01) and more (psychotic) major depression (p = 0.003), but in addition also more (psychotic) bipolar disorder (p = 0.05) than women in the NFBC 1966 (c.f. Supplementary material 2). Especially up to age 18, women in the NFBC 1986 had the highest cumulative incidence of psychosis (see Fig. 1). Among female members of the NFBC 1986 with psychosis up to age 18 32% (n = 10) had schizophrenia (narrow), 13% (n = 4) had schizophrenia spectrum disorder, 6.5% (n = 2) had bipolar disorder (psychotic), 22.5% (n = 7) had major depression (psychotic), 10% (n = 3) brief psychosis and 16% (n = 5) had other non-organic psychoses (not shown in tables).

Schizophrenia v. all other psychosis

Prevalence of risk factors was compared between subjects with schizophrenia diagnosis v. all other psychoses within cohorts. There were significantly more male individuals with schizophrenia than with all other psychoses in the NFBC 1986 (p = 0.045). However, no other statistical differences were observed (not shown in tables).

Discussion

Main findings

Even if the cumulative incidence of schizophrenia remained the same when the two cohorts, set up 20 years apart were compared, that for all psychoses increased (from 1.0 to 1.9%). Also the onset, based on first treatment or disability pension, had become earlier. The highest risk for early onset shifted from men to young women. Of the studied risk factors for psychosis, only parental psychosis was a significant risk factor of psychosis (HR ≥ 3.0) in both cohorts.

Time trends in the incidence of schizophrenia

Studies from high-income countries across time are inconsistent, some reported a decline in the incidence of schizophrenia (range: −9 to −66%), no change or an increase in incidence rates (range: +18 to +64%) (Warner, 2004). The incidence of schizophrenia in Finland has declined in cohorts born between 1954 and 1965 (Suvisaari et al. 1999). In the 1980s, first admission rates due to schizophrenia decreased with only slightly increase thereafter (Salokangas et al. 2011). The life-time schizophrenia prevalence in an internal isolate from Northeastern Finland has been higher (2.2%) compared with other regions (1.2%) in Finland (Hovatta et al. 1997). In the present study, NFBCs represent mainly other northern regions. Thus, genetic predisposition, while being probably a strong contributing factor, might not entirely explain higher psychosis incidence in Northern Finland. Future research should explore gene environment interaction.

Changes in risk factors in respect to incidence of psychosis

In the two NFBCs, the proportions of risk factors of psychosis had both increased as well as decreased within 20 years, e.g. rural residence earlier parental age and low maternal education were less frequent in the NFBC 1986. On the other hand, more infants with low birth weight <2500 g should have survived to adulthood due to improved quality of health care and it could increase the incidence of psychosis. The analysis showed that the difference in incidence of psychosis between the two cohorts was not dependent on change in prevalence of risk factors, since after the adjustment for potential risk factors the decrease in pooled HR (NFBC 1986 v. NFBC 1966) was only 8% (not presented in tables). Paternal age has not been associated with increased psychosis risk in either of the NFBCs, but in a meta-analysis – including also the NFBC 1966 – advanced paternal age was linked with psychosis risk (relative risk, RR = 1.65; 1.46–1.89; p < 0.01). The recent meta-analysis by Rasic et al. (2013) has shown that at age 20 and over offspring of parents with schizophrenia had 7.87 RR of schizophrenia (95% CI 4.14–14.94, p < 0.001), that is lower compared to previously found 13% risk (Gottesman, 1991). Also the recent follow-up of NFBC 1966 (age of 46) found that parental psychosis increased risk for any psychosis only with HR 2.9 (95% CI 1.90–4.89) (Keskinen, 2015).

In the present study only limited amount of early risk factors could be investigated. Data on, e.g. childhood adversities/stress were not collected and data for adolescence cannabis use were not available for NFBC 1966. In the 1990s, an increase in the number of psychiatric inpatients consuming illegal drugs was observed in Finland (Pirkola & Sohlman, 2005), but in the NFBC 1966 there were no cases of schizophrenia with a cannabis abuse (Koskinen et al. 2010). Later in the NFBC 1986, adolescent cannabis use was linked with prodromal symptoms of psychosis (Miettunen et al. 2008). Migration could also affect the risk of psychosis (Matheson et al. 2014), but the NFBCs have a homogeneous population with very low prevalence of non-Finnish parents.

Diagnostic system changes

Diagnostic changes are a methodological challenge. During the total 40 years of the NFBCs, the diagnostic system has changed from ICD 8 via ICD 9 to ICD 10. During ICD 8 period Finnish psychiatrists followed the Bleulerian principles in diagnosing schizophrenia, i.e. preferring schizophrenia for manic depressive illness (Salokangas, 1985). In the time of the ICD 9, the diagnostic criteria for mental disorders were adopted with slight modification from DSM–III–R, which had narrower definition for schizophrenia and a requirement of 6-month duration of symptoms (Kuoppasalmi et al. 1989). Later, in the ICD 10 it is only 1 month as was the case also for schizophreniform disorder in ICD 8/9. Thus, schizophreniform disorder was included to schizophrenia (narrow) in the present study. Diagnostic practices have been assessed in the NFBC 1966, firstly up to 1993 and then up to 1997, showing that 43 and 48% of schizophrenia cases were diagnosed as ‘schizophreniform disorder’ and ‘other psychosis’ (Isohanni et al. 1997; Moilanen et al. 2003). In NFBC 1986, such studies have not been conducted. Even if this should not dramatically bias our results, the shift from schizophrenia to other types of psychoses might include some misclassifications due to the change in diagnostic practise over the period (Munk-Jorgensen, 1986; Allardyce et al. 2000; Sorvaniemi et al. 2006).

Health system changes and new registers

Schizophrenia can be seen as a continuum of symptomatology (Van Os et al. 2009) and early detection of first-episode psychosis increases the chances of milder deficits and superior functioning (ten Velden Hegelstad et al. 2012). According to clinical staging model, earlier identification and referral of those at risk of psychosis in a non-stigmatising way (by e.g. school counsellors, primary/specialist care) play essential role in early prevention (Scott et al. 2013). As a result of the mental healthcare actions in Finland, outpatient mental health visits increased (from 1.6 million to 2.3 million) during 1997–2010 period (Pirkola & Sohlman, 2005). The admissions of adolescent patients more than doubled between 1991 and 2003 (Salokangas et al. 2011). Earlier psychosis detection due to more options in mental health services could partially explain higher rates of psychosis in the NFBC 1986 than in the NFBC 1966, but also the decrease of the most severe forms of psychosis. Differences in incidence and onset (NFBC 1986 v. NFBC 1966) may be explained, at least partially, by earlier help-seeking behaviour and detection in younger people, especially in those with affective symptoms, which may be considered as a prodromal stage of psychosis. That also could explain higher incidence among females.

Early screening should result in decreased duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), but the time trends of DUP among adolescents have not been studied and no large-scale prevention programmes have been conducted among them in Northern Finland. A review by Singh (2007) observed that in 13 selected studies from high-income countries mean DUP varied from 25 to 722.8 months. In the NFBC 1966, DUP was 33.02 weeks (Penttilä et al. 2010), which is shorter compared with almost all studies in this review. However, there is no evidence to state that DUP in NFBC 1986 is shorter than in NFBC 1966. Thus, health system changes could have an effect on incidence of psychosis in Northern Finland, but this requires further research.

The new registers available in the NFBC 1986 (v. NFBC 1966) could have increased the number of identified cases. However, the proportion of outpatients was low and fully covered by SII registries in the NFBC 1966. Due to deinstitutionalisation, the out-patients registers play more important role for cases identification in NFBC 1986 than in the NFBC 1966, but should not have had any major effect on the results. Parental psychosis data were available only since 1962 and it could result in underestimation of parental psychosis in NFBC 1966.

Strengths

The use of two cohorts set up 20 years apart covering the same geographic region is the main strength allowing greater comparability of two cohorts. The prospective data collection from two successive subjects’ generations (Rantakallio, 1988) and the use of Finnish national registers with good validity and high coverage (Sund, 2012) are the other strengths. The birth cohort design allowed us to study very early as well as some prospectively collected risk factors.

Limitations

The comparison of the two cohorts only up to the age 27 years based on the follow-up available in NFBC 1986. In the latest NFBC 1966 follow-up in 2012 (age 46 years), the incidence of psychosis was 3.1 and 46.5% among diagnosed had schizophrenia, 13.1% had bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms and 33.1% had depression with psychotic symptoms (Keskinen, 2015). Still, when comparing the two cohorts until the age 27, the peak risk period for developing a psychosis (adolescence) is included (Paus et al. 2008). The samples include only help-seeking/treated cases and the results could at least partially be influenced by trends in diagnostic practise and the mental health services reorganisation that took place in Finland. It might be that affective psychoses and non-schizophrenia cases were under-diagnosed and untreated in the NFBC 1966 even though their incidence in early adulthood may be low (Mäki et al. 2010), while earlier detection of cases could have been possible in the NFBC 1986. Thus, some of the results are based on few cases. Still, the quality of Finnish register is high and according to a study by Perälä et al. (2007) the underestimation of cases was only 25% in CRHC and 13.7% in all other registers. Lastly, non-studied or not collected risk factors may have also affected the incidence of psychosis at least in some extent.

In conclusion, comparison of the two birth cohorts within 20 years covering altogether a period of 40 years showed increase in incidence of psychosis in younger NFBC 1986. Shift in types of diagnosis, to less severe psychoses, and to earlier onset, especially among women, were found. Studied risk factors did not explain the time trends of psychosis. The observed differences could be due to real changes in incidence or they can be attributable to changes in diagnostic practices, or to early psychosis detection and treatment. However, more research is needed to explore reasons for these changes.

Acknowledgements

We thank the late Professor Paula Rantakallio (1930–2013) (launch of NFBC 1966) and Professor Anna-Liisa Hartikainen (launch of NFBC 1986), the participants in the study and the NFBC project center. We acknowledge the financial support received from the listed below foundations.

Financial support

The research leading to these results has received funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007–2013 under REA grant agreement no 316795 and the Academy of Finland (#132071, #268336, #278286), the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation, the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, and the Northern Finland Health Care Support Foundation, and the Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, Finland.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000123.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- Allardyce J, Morrison G, Van Os J, Kelly J, Murray RM, McCreadie RG (2000). Schizophrenia is not disappearing in south-west Scotland. British Journal of Psychiatry 177, 38–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamrah JS, Freeman HL, Goldberg DP (1991). Epidemiology of schizophrenia in Salford, 1974–84. Changes in an urban community over ten years. British Journal of Psychiatry 159, 802–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin J, Cantwell R, Dalkin T, Fox R, Medley I, Glazebrook C, Kwiecinski R, Harrison G (1997). Incidence of schizophrenia in Nottingham. A comparison of two cohorts, 1978–80 and 1992–94. British Journal of Psychiatry 171, 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman II (1991). Schizophrenia Genesis: The Origins of Madness, p. 96 WH Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O (1991). Gender and schizophrenia: age at onset and sociodemographic attributes. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 83, 402–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häfner H, an der Heiden W (1986). The Mannheim case register: the long-stay population In Psychiatric Case Registers in Public Health (ed. ten Horn GHMM, Giel R, Gulbinat WH and Henderson JH), pp. 28–50, Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Haukka J, Suvisaari J, Varilo T, Lonnqvist J (2001). Regional variation in the incidence of schizophrenia in Finland: a study of birth cohorts born from 1950 to 1969. Psychological Medicine 31, 1045–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovatta I, Terwilliger JD, Lichtermann D, Makikyro T, Suvisaari J, Peltonen L, Lonnqvist J (1997). Schizophrenia in the genetic isolate of Finland. American Journal of Medical Genetics 74, 353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isohanni M, Makikyro T, Moring J, Rasanen P, Hakko H, Partanen U, Koiranen M, Jones P (1997). A comparison of clinical and research DSM-III-R diagnoses of schizophrenia in a Finnish national birth cohort. Clinical and research diagnoses of schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32, 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isohanni M, Miettunen J, Maki P, Murray GK, Ridler K, Lauronen E, Moilanen K, Alaraisanen A, Haapea M, Isohanni I, Ivleva E, Tamminga C, McGrath J, Koponen H (2006). Risk factors for schizophrenia. Follow-up data from the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. World Psychiatry 5, 168–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablensky A (2000). Epidemiology of schizophrenia: the global burden of disease and disability. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 250, 274–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendell RE, Malcolm DE, Adams W (1993). The problem of detecting changes in the incidence of schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 162, 212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskinen E. (2015) Parental psychosis, risk factors and protective factors for schizophrenia and other psychosis. The Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966. Retrieved 05. 01. 2016 from http://herkules.oulu.fi/isbn9789526210483/isbn9789526210483.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Keskinen E, Miettunen J, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Mäki P, Isohanni M, Jääskeläinen E (2013). Interaction between parental psychosis and risk factors during pregnancy and birth for schizophrenia – the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort study. Schizophrenia Research 145, 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandaker G, Clarke M, Cannon M, Jones P (2014). Life course approach to specific mental disorders: schizophrenia and related psychosis In Life Course Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ed. Koenen K, Rudenstine S, Susser E and Galeo S), p. 64, Oxford University Press: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride JB, Croudace T, Brewin J, Donoghue K, Mason P, Glazebrook C, Medley I, Harrison G, Cooper JE, Doody GA, Jones PB (2009). Is the incidence of psychotic disorder in decline? Epidemiological evidence from two decades of research. International Journal of Epidemiology 38, 1255–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride JB, Errazuriz A, Croudace TJ, Morgan C, Jackson D, Boydell J, Murray RM, Jones PB (2012). Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in England, 1950–2009: a systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 7, e31660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhaus K, Harlap S, Perrin M, Manor O, Weiser M, Lichtenberg P, Malaspina D (2011). Age, sex and first treatment of schizophrenia in a population cohort. Journal of Psychiatric Research 45, 136–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen J, Lohonen J, Koponen H, Isohanni M, Miettunen J (2010). Rate of cannabis use disorders in clinical samples of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 36, 1115–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuoppasalmi K, Lönnqvist J, Pylkkänen K, Huttunen M (1989). Classification of mental disorders in Finland. A comparison of the Finnish classification of mental disorders in 1987 with DSM III-R. Psychiatria Fennica 20, 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Laurens KR, Luo L, Matheson SL, Carr VJ, Raudino A, Harris F, Green MJ (2015). Common or distinct pathways to psychosis? A systematic review of evidence from prospective studies for developmental risk factors and antecedents of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders and affective psychoses. BMC Psychiatry 15, 205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB (2007). A comparison of selected risk factors for unipolar depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia from a Danish population-based cohort. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68, 1–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen V, Taipale V (2001). Integrating mental health services: the Finnish experience. International Journal of Integrated Care 1, e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäki P, Riekki T, Miettunen J, Isohanni M, Jones P, Murray G, Veijola J (2010). Schizophrenia in the offspring of antenatally depressed mothers in the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort – relationship to family history of psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry 167, 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson SL, Shepherd AM, Laurens KR, Carr VJ (2011). A systematic meta-review grading the evidence for non-genetic risk factors and putative antecedents of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 133, 133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson SL, Shepherd AM, Carr VJ (2014). How much do we know about schizophrenia and how well do we know it? Evidence from the Schizophrenia Library. Psychological Medicine 44, 3387–3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Saha S, Welham J, El Saadi O, MacCauley C, Chant D (2004). A systematic review of the incidence of schizophrenia: the distribution of rates and the influence of sex, urbanicity, migrant status and methodology. BMC Medicine 2, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna K, Gordon CT, Lenane M, Kaysen D, Fahey K, Rapoport JL (1994). Looking for childhood-onset schizophrenia: the first 71 cases screened. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33, 636–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettunen J (2011). Use of register data for psychiatric epidemiology in the Nordic countiries In Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology (ed. Tsuang M, Tohen M and Jones PB), pp. 117–131. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Miettunen J, Tormanen S, Murray GK, Jones PB, Mäki P, Ebeling H, Moilanen I, Taanila A, Heinimaa M, Joukamaa M, Veijola J (2008). Association of cannabis use with prodromal symptoms of psychosis in adolescence. British Journal of Psychiatry 192, 470–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B, Messias E, Miettunen J, Alaraisanen A, Jarvelin MR, Koponen H, Rasanen P, Isohanni M, Kirkpatrick B (2011). Meta-analysis of paternal age and schizophrenia risk in male versus female offspring. Schizophrenia Bulletin 37, 1039–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen K, Veijola J, Laksy K, Makikyro T, Miettunen J, Kantojarvi L, Kokkonen P, Karvonen JT, Herva A, Joukamaa M, Jarvelin MR, Moring J, Jones PB, Isohanni M (2003). Reasons for the diagnostic discordance between clinicians and researchers in schizophrenia in the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38, 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk-Jorgensen P (1986). Decreasing first-admission rates of schizophrenia among males in Denmark from 1970 to 1984. Changing diagnostic patterns? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 73, 645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myhrman A, Rantakallio P, Isohanni M, Jones P, Partanen U (1996). Unwantedness of a pregnancy and schizophrenia in the child. British Journal of Psychiatry 169, 637–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ösby U, Hammar N, Brandt L, Wicks S, Thinsz Z, Ekbom A, Sparen P (2001). Time trends in first admissions for schizophrenia and paranoid psychosis in Stockholm County, Sweden. Schizophrenia Research 47, 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 9, 947–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penttilä M, Jääskeläinen E, Haapea M, Tanskanen P, Veijola J, Ridler K, Murray GK, Barnes A, Jones PB, Isohanni M, Koponen H, Miettunen J (2010). Association between duration of untreated psychosis and brain morphology in schizophrenia within the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Schizophrenia Research 123, 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perälä J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, Kuoppasalmi K, Isometsa E, Pirkola S, Partonen T, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Hintikka J, Kieseppa T, Harkanen T, Koskinen S, Lonnqvist J (2007). Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 64, 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perälä J, Saarni SI, Ostamo A, Pirkola S, Haukka J, Härkänen T, Koskinen S, Lönnqvist J, Suvisaari J (2008). Geographic variation and sociodemographic characteristics of psychotic disorders in Finland. Schizophrenia Research 106, 337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkola S, Sohlman B (2005). Atlas of Mental Health: Statistics from Finland. National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health: Helsinki, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Rantakallio P (1988). The longitudinal study of the northern Finland birth cohort of 1966. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 2, 59–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasic D, Hajek T, Alda M, Uher R (2013). Risk of mental illness in offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of family high-risk studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin 40, 28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salokangas RK (1985). Towards comprehensive care in schizophrenia. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 39, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Salokangas RK, Helminen M, Koivisto AM, Rantanen H, Oja H, Pirkola S, Wahlbeck K, Joukamaa M (2011). Incidence of hospitalised schizophrenia in Finland since 1980: decreasing and increasing again. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 46, 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Leboyer M, Hickie I, Berk M, Kapczinski F, Frank E, Kupfer D, McGorry P (2013). Clinical staging in psychiatry: a cross-cutting model of diagnosis with heuristic and practical value. British Journal of Psychiatry 202, 243–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S (2007). Outcome measures in early psychosis Relevance of duration of untreated psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 191, s58–s63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorvaniemi M, Alho A, Kesti S, Mattila S, Moglia P, Parssinen H, Raittio N, Vattulainen K (2006). Improved detection and pharmacotherapy of major depression from 1989 to 2001 in psychiatric outpatient care in Finland. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 60, 239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Finland Population (2015). Retrieved 2. 12. 2015 from http://www.stat.fi/tup/suoluk/suoluk_vaesto_en.html.

- Sund R (2012). Quality of the finnish hospital discharge register: a systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 40, 505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvisaari JM, Haukka JK, Tanskanen AJ, Lonnqvist JK (1999). Decline in the incidence of schizophrenia in Finnish cohorts born from 1954 to 1965. Archives of General Psychiatry 56, 733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei N, Lewis G, Sham PC, Murray RM (1996). Age-period-cohort analysis of the incidence of schizophrenia in Scotland. Psychological Medicine 26, 963–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Velden Hegelstad W, Larsen TK, Auestad B, Evensen J, Haahr U, Joa I, Johannesen JO, Langeveld J, Melle I, Opjordsmoen S, Rossberg JI (2012). Long-term follow-up of the TIPS early detection in psychosis study: effects on 10-year outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry 169, 374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L (2009). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness–persistence–impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychological Medicine 39, 179–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, Lieverse R, Lataster T, Viechtbauer W, Read J, van Os J, Bentall RP (2012). Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective-and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin 38, 661–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner R (2004). Recovery from Schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Political Economy. Routledge: Hove, East Sussex BN3 2FA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000123.

click here to view supplementary material