Abstract

Aims

There are an estimated 1.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Ukraine because of the armed conflict in the east of the country. The aim of this paper is to examine utilisation patterns of mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) care among IDPs in Ukraine.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey design was used. Data were collected from 2203 adult IDPs throughout Ukraine between March and May 2016. Data on mental health care utilisation were collected, along with outcomes including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety. Descriptive and multivariate regression analyses were used.

Results

PTSD prevalence was 32%, depression prevalence was 22%, and anxiety prevalence was 17%. Among those that likely required care (screened positive with one of the three disorders, and also self-reporting a problem) there was a large treatment gap, with 74% of respondents who likely required MHPSS care over the past 12 months not receiving it. For the 26% (N = 180) that had sought care, the most common sources of services/support were pharmacies, family or district doctor/paramedic (feldsher), neurologist at a polyclinic, internist/neurologist at a general hospital, psychologists visiting communities, and non-governmental organisations/volunteer mental health/psychosocial centres. Of the 180 respondents who did seek care, 163 could recall whether they had to pay for their care. Of these 163 respondents, 72 (44%) recalled paying for the care they received despite government care officially being free in Ukraine. The average costs they paid for care was US$107 over the previous 12 months. All 180 respondents reported having to pay for medicines and the average costs for medicines was US$109 over the previous 12 months. Among the 74% had not sought care despite likely needing it; the principal reasons for not seeking care were: thought that they would get better by using their own medications, could not afford to pay for health services or medications, no awareness of where to receive help, poor understanding by health care providers, poor quality of services, and stigma/embarrassment. The findings from multivariate regression analysis show the significant influence of a poor household economic situation on not accessing care.

Conclusions

The study highlights a high burden of mental disorders and large MHPSS treatment gap among IDPs in Ukraine. The findings support the need for a scaled-up, comprehensive and trauma-informed response to provision of MHPSS care of IDPs in Ukraine alongside broader health system strengthening.

Key words: Ukraine, mental health, war, refugee, health services, access

Introduction

There are an estimated 1.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Ukraine because of the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine between the Ukrainian army and pro-Russian separatist forces. IDPs in Ukraine have experienced multiple types of trauma exposure such as forced displacement, bombardment, being caught in war fighting, injury and assault (UNOCHA, 2015). The IDPs are living in a combination of private accommodation or in collective settlements (e.g., temporary settlements such as camps, former hotels, hospitals and schools). Unemployment is high and access to social support services appears limited. These are all well-recognised risk factors for elevated levels of mental disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety (Miller & Rasmussen, 2009; Steel et al. 2009; WHO & UNHCR, 2012).

There is therefore a need in Ukraine for mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) interventions and community mobilisation to improve mental health outcomes, relieve individual suffering and improve functioning. Government services in Ukraine for mental disorders are offered to all Ukrainian citizens, with the majority of services delivered by specialists in polyclinics, psychiatric hospitals, and psychiatric departments in general hospitals. In principal, mental health services should be free of charge, while out-patients have to purchase their own medications in an outpatient setting, but inpatients also frequently need to contribute to pharmaceutical costs (Lekhan et al. 2015). Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and private sector providers are also providing MHPSS services.

Evidence and guidelines from other conflict-affected settings strongly support the need for scaled-up and comprehensive responses to promote the mental health of conflict-affected populations, including trauma-informed policies that will guide the mental health system and services (IASC, 2007; WHO, 2013). However, there is very limited research on utilisation of health services among conflict-affected civilians in low- and middle-income countries, which is where the vast majority of conflict-affected civilians live. To the best of our knowledge, no such data have been collected in Ukraine despite the very high numbers of IDPs and the need for reliable epidemiological data to inform appropriate MHPSS responses there. The aim of this paper is to examine utilisation patterns of MHPSS care among IDPs in Ukraine.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted throughout Ukraine (except the territories currently not controlled by Ukrainian government) with IDPs aged 18 years and over between March and May 2016. An IDP was considered as someone who answered the questionnaire-screening question that they had been forced to flee their homes because of the fighting and is currently living away from their home, following agreed definitions for IDPs (Deng, 1998). Exclusion criteria included people deemed under the influence of alcohol or drugs, and those with severe intellectual or mental impairment, at the time of the survey. The survey sought to be as nationally representative as possible of IDPs in Ukraine, and took place in 25 Oblasts with high numbers of IDPs.

Time–location sampling was chosen as a probabilistic method to recruit hard-to-reach and migrant populations (Fisher Raymond et al. 2007; Tyldum & Johnston, 2014). The sampling procedure involved contacting IDPs in the places of gathering (e.g., hostels for IDPs, state services, volunteer organisations and NGOs, places of the distribution of humanitarian aid). The sampling framework consists of time–location units which represent the potential universe of places, days and times, where and when target group can be accessed. In our study, 33% of the respondents were recruited in collective centres, 31% in NGOs working with IDPs, and 6% in state institutions. 24% were contacted with the help of another person (informant), and 6% were reached by other means (for example, in church or with door-to-door survey method). In total, 121 unique locations were used for recruiting during the survey (not counting the private dwellings and working places of the respondents reached with the help of informants).

Survey questionnaire

The questionnaire included questions on demographic socio-economic and displacement characteristics, and screening measures for mental disorders. The outcome measures were PTSD, depression and anxiety as these are the common disorders among conflict-affected populations (de Jong et al. 2003; Porter & Haslam, 2005; Blanchet et al. 2017). These measures were the PCL-5 for PTSD with a question recall period of previous 1 month, and screening cut-off score >33 (Blevins et al. 2015); the PHQ-9 for depression with a recall period of previous 2 weeks and cut-off score ≥10 (Kroenke et al. 2001); and the GAD-7 for anxiety with a recall period of previous 2 weeks and cut-off score ≥10 (Spitzer et al. 2006). These outcome measures have been used and validated in a wide range of cultural and linguistic settings, including populations affected by conflict. The PCL-5, PHQ-9 and GAD-7 showed good reliability in our main study sample (N = 2203), with Cronbach's alpha scores of 0.95, 0.90, 0.92 respectively; and results from a separate test–retest mini survey (N = 110) produced intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) of 0.83, 0.84 and 0.89, respectively. For validity in the main study sample (N = 2203), principal component analysis showed high construct validity, with strong associations (>0.7) between individual items and a single underlying construct for each measure: with the PCL-5 scoring 17 items >0.7 and the remaining 3 items >0.6; the PHQ-9 scoring 8 items >0.7 and 1 item >0.6; and the GAD-7 scoring all 7 items >0.7 (see Online Annex 1 for individual item scores). Construct validity was also supported by Pearson Correlation Tests showing strong (>0.7) associations between the instruments as would be expected (PCL-5 and PHQ-9 = 0.78; PCL and GAD-7 = 0.76; and PHQ-9 and GAD-7 = 0.72).

Respondents were also asked whether they had feelings such as anxiety, nervousness, depression, insomnia or any other emotional or behavioural problems for which they sought health care during the 12 months prior to interview. Those that had sought some kind of care were then asked the source of services/support (see Table 2 for these sources) and the type of care (medications, psychosocial support and counselling/psychotherapy). Psychosocial support refers to ‘any type of local or outside support that aims to protect or promote psychosocial well-being and/or prevent or treat mental disorders’. Counselling refers to a conversation with a doctor/related health professional giving advice, and psychotherapy refers to treatment without medications through interactions with a specialist (psychologist, psychiatrist). The costs of the care were also recorded through a question worded as: ‘overall, approximately how much did you have to spend for your treatment and medicines (including formal and informal payments)?’ This was recorded in the Ukrainian currency of Hryvnia and, for the purposes of this paper, then converted to US dollars at the average exchange rate during the data collection period (Exchange Rates site, 2017). Respondents who self-reported having mental, emotional or behavioural problems, but did not use health services, were asked additional questions about reasons for not seeking care.

Table 2.

Sources of external services/support for respondents who self-reported problems and screened with a mental disorder and who sought care (N = 180, multiple answers allowed)

| Source of services/support | Care type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medications | Psychosocial support | Counselling/psychotherapy | Total | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N | |

| Pharmacy | 87 (48.57) | 87 | ||

| Family or district doctor/paramedic | 40 (22.19) | 20 (11.26) | 9 (5.12) | 69 |

| Neurologist at polyclinic | 28 (15.37) | 15 (8.22) | 17 (9.87) | 60 |

| Internist/neurologist at general hospital | 30 (16.47) | 9 (4.92) | 16 (8.98) | 55 |

| Psychologists visiting communities | 34 (19.06) | 15 (8.15) | 49 | |

| NGO/volunteer mental health/psychosocial centre | 21 (11.87) | 17 (9.52) | 38 | |

| Private mental health specialist | 6 (3.07) | 11 (6.03) | 5 (2.90) | 22 |

| Church | 22 (11.95) | 22 | ||

| Emergency care | 6 (3.16) | 1 (0.56) | 1 (0.56) | 8 |

| Psychiatric dispensary | 1 (0.56) | 3 (1.59) | 2 (0.94) | 6 |

| Home visits by social workers | 5 (2.98) | 1 (0.56) | 6 | |

| Alternative/traditional health provider | 2 (1.02) | 1 (0.78) | 3 | |

| Psychiatric hospital | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 |

| Total | 199 | 143 | 84 | |

Notes: Multiple answers allowed. % denominator is N = 180 (respondents who self-reported mental health and emotional problems and with symptoms of PTSD (PCL-5 Score >33), depression (PHQ-9 score ≥10) or anxiety (GAD-7 score ≥10) and who sought care).

The survey questionnaire was developed in English and underwent adaptation and translation process into Ukrainian and Russian based on best practice procedures to ensure reliability, validity and appropriateness with the study population (Van Ommeren et al. 1999). The questionnaires were administered in either Ukrainian or Russian by trained enumerators from the Kiev International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) through face-to-face interviews in the place agreed with the respondent. Before administering the questionnaire, each respondent listened to the explanations about the aim of the survey and terms of participation. In addition, the respondent received an information sheet and consent form and then gave either written or verbal consent. Ethical approval was provided by the KIIS Institutional Review Board.

Data analysis

Descriptive and multivariate regression analyses were conducted. To describe the treatment gap, the proportion of individuals who required MHPSS care but did not receive treatment was calculated. The definition of those requiring care was respondents who reported that they had not used services despite reporting mental, emotional or behavioural problems over the past 12 months and who also screened positive with one or more of PTSD, depression and anxiety (based upon the above cut-offs for PCL-5, PHQ-9 and GAD-7). To assess the influence of different factors on health service utilisation, multivariate logistic regression was conducted. The dependent variable was service utilisation in the past 12 months (as defined above). Key independent variables were selected based on evidence from related previous studies and these included gender, age, economic situation and severity of mental disorders. All data were weighted to reflect the true geographic distribution of IDPs in the different Oblasts of Ukraine. Statistical significance was assumed at p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 14.

Results

A total of 2203 questionnaires were completed and the overall response rate was 89%. The 58% of interviews took place in regional cities, 40% in other cities and towns, and 2% in villages. The sample characteristics are given in Table 1. Over two-thirds of respondents were women (68% women, 32% men). The gender ratio in the study conforms to national statistics (State Employment Service, 2016) and results of other surveys of IDPs in Ukraine (UNOCHA, 2015; Summers et al. 2016). The majority of respondents rated their household economics situation as bad or very bad (59%). Only 22% of respondents were in regular paid work. The average length of current displacement was 18 months.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 2203)

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 704 (31.9) |

| Women | 1499 (68.1) | |

| Age | 18–30 | 480 (21.8) |

| 31–44 | 711 (32.3) | |

| 45–59 | 522 (23.6) | |

| 60–74 | 356 (16.2) | |

| 75 and over | 134 (6.1) | |

| Education | Incomplete secondary or less | 114 (5.2) |

| Secondary education/technical equivalent | 528 (24.0) | |

| Secondary technical education/ incomplete higher education | 767 (34.9) | |

| Higher education | 790 (35.9) | |

| Occupation | Regular paid work | 489 (22.4) |

| Irregular paid work | 216 (9.9) | |

| Self-employed | 61 (2.8) | |

| Unemployed/seeking work | 391 (17.9) | |

| Housewife | 81 (3.7) | |

| Maternity leave | 157 (7.2) | |

| Retired due to old age or disability | 631 (28.8) | |

| Other | 159 (7.3) | |

| Household economic situation | Very good | 15 (0.7) |

| Good | 95 (4.5) | |

| Average | 755 (35.7) | |

| Bad | 989 (46.7) | |

| Very bad | 261 (12.4) | |

| Displacement | Average length (months) of current displacement (min; max) | 18 (1.26) |

The rates of mental disorders among IDPs were high, particularly among women (Fig. 1). The prevalence of symptoms of PTSD was 32% (22% men; 36% women), for depression it was 22% (16% men; 25% women), and for anxiety was 18% (13% men; 20% women).

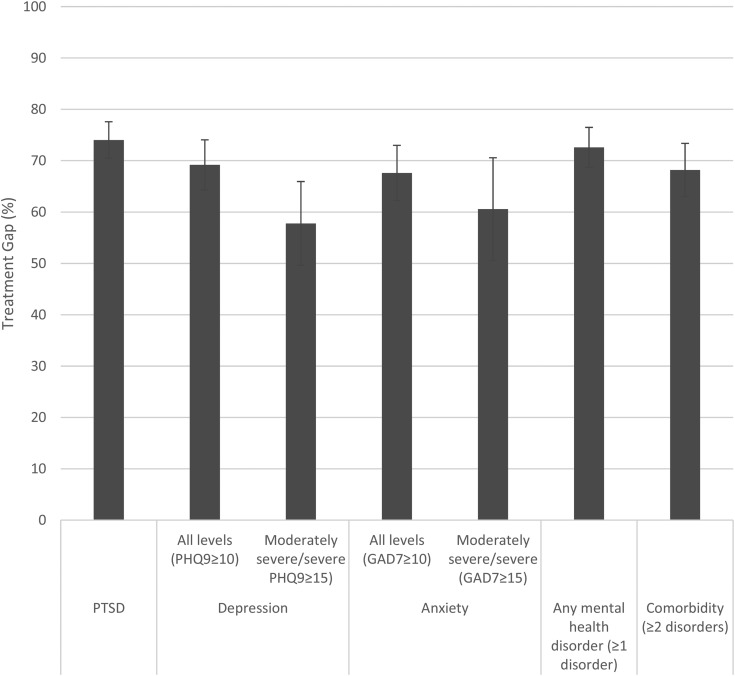

Fig. 1.

Treatment gap – proportion of respondents reporting mental health problems in the previous 12 months and also screened with mental disorder symptoms but who did not access care, by disorder (N = 703).

Health care utilisation and costs of care

Respondents were asked whether they had experienced any kind of mental health or emotional problem over the previous 12 months. There were 703 respondents who had experienced such problems and were also screened positive with PTSD, depression or anxiety in our questionnaire. Of the 703 respondents, 180 had sought care. The sources of services and support utilised by these 180 respondents are provided in Table 2. The most common sources of services/support were: pharmacy (N = 87); family or district doctor/paramedic (N = 69); internist at a polyclinic (N = 60); internist/neurologist at a general hospital (N = 55); psychologists visiting communities (N = 49); and NGO/volunteer mental health/psychosocial centre (N = 38). Within these, the most common care type was medications (N = 199), psychosocial support (N = 143), and then counselling (N = 84). The sources of services and support by disorder type are provided in Table 3. The most significant difference was the greater reliance on pharmacies for medication for those with depression and anxiety compared with those with PTSD; whereas those with PTSD made greater use of a family doctor and visiting psychologist for psychosocial support.

Table 3.

Sources of external services/support for respondents who self-reported problems and screened with a disorder and who sought care, by disorder type (multiple answers allowed)

| PTSD (N = 152)* | Depression (N = 108)* | Anxiety (N = 96)* | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care type | Care type | Care type | ||||||||||

| Source of services/support | Medica-tion (%) | Psycho-social support (%) | Counse-lling/psycho-therapy (%) | Total N | Medica-tion (%) | Psycho-social support (%) | Counse-lling/psycho-therapy (%) | Total N | Medica-tion (%) | Psycho-social support (%) | Counse-lling/psycho-therapy (%) | Total N |

| Pharmacy | 49.00 | 74 | 60.44 | 64 | 53.73 | 51 | ||||||

| Family or district doctor/paramedic | 23.95 | 12.40 | 4.83 | 62 | 22.61 | 7.57 | 4.72 | 37 | 22.83 | 5.01 | 4.93 | 28 |

| Neurologist at Polyclinic | 14.92 | 7.39 | 11.58 | 50 | 16.98 | 7.89 | 9.08 | 36 | 18.37 | 10.35 | 12.52 | 36 |

| Internist/neurologist at general hospital | 17.68 | 5.63 | 10.32 | 50 | 21.71 | 5.04 | 10.05 | 39 | 23.39 | 4.17 | 12.22 | 36 |

| Psychologists visiting communities | 18.58 | 7.42 | 39 | 14.43 | 6.30 | 22 | 20.36 | 7.52 | 25 | |||

| NGO/volunteer mental health/psychosocial centre | 11.24 | 9.14 | 31 | 8.60 | 7.65 | 17 | 15.00 | 13.03 | 25 | |||

| Private mental health specialist | 2.10 | 3.33 | 2.66 | 12 | 1.74 | 4.16 | 3.50 | 10 | 4.42 | 8.29 | 2.10 | 13 |

| Church | 11.34 | 17 | 8.83 | 9 | 10.87 | 10 | ||||||

| Emergency care | 3.70 | 0.27 | 0.75 | 7 | 2.96 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 4 | 5.44 | 0.42 | 1.19 | 6 |

| Psychiatric dispensary | 0.32 | 1.86 | 1.10 | 5 | 0.43 | 2.50 | 1.48 | 5 | 0.26 | 2.95 | 1.74 | 4 |

| Home visits by social workers | 3.50 | 0.27 | 6 | 4.01 | 0.36 | 5 | 2.63 | 0.42 | 3 | |||

| Alternative/traditional health provider | 1.20 | 0.91 | 3 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | |||

| Psychiatric hospital | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 |

Notes: multiple answers allowed.

PTSD PCL-5 Score >33, depression PHQ-9 score ≥10, anxiety GAD-7 score ≥10. Results by disorder include cases with >1 disorder. % denominator is total with the disorder who had sought care. Total N is the total number with the disorder who sought that particularly source of services/support.

Of the 180 respondents who did seek care, 163 could recall whether they had to pay for their care. Of these 163 respondents, 72 (44%) recalled paying for the care they received. The average costs they paid for care was US$107 over the previous 12 months. All 180 respondents reported having to pay for medicines and the average costs for medicines was US$109 over the previous 12 months. In order to explore variance in costs by disorder type, a sub-group analysis was conducted of respondents with a single disorder only (rather than multiple disorders). The respective costs for those with only PTSD who had to pay were US$171 for care (N = 31) and US$154 for medicines (N = 57), while for depression only it was US$42 for care (N = 17) and US$80 for medicines (N = 36), and for anxiety only it was US$40 for care (N = 11) and US$98 for medicines (N = 21). However, the sample size was quite small for this sub-group analysis and so variance in cost by outcome could be due to artefact.

When the 180 respondents were asked how much they felt the treatment helped them, 6% felt it had helped a lot, 19% felt it had helped somewhat, 57% felt it had helped only a little, and 18% felt it not helped at all. When they were asked how satisfied they felt with their care, 10% were very satisfied, 26% satisfied, 39% were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 13% were dissatisfied, and 12% were very dissatisfied. There were no significant differences in a sub-group analysis of respondents with the different disorders with regard to either perceived effectiveness or satisfaction.

Treatment gap

Of the 703 respondents who reported having a mental health or emotional problem over the previous 12 months and who also screened positive with PTSD, depression, or anxiety, 520 respondents did not seek care (there were missing data for the remaining three respondents). This equates to an overall treatment gap of 74% (95% CI 70.99–77.55). When broken down by condition, the treatment gap was 74% (95% CI 70.47–77.60) for PTSD, 69% (95% CI 64.31–74.05) for depression, and 68% (95% CI 62.25–72.99) for anxiety. There were no statistically significant differences in the treatment gap between men and women. Notably, the treatment gap remains high even for more severe levels of disorders, at 57% (95% CI 49.62–65.95) for severe depression (PHQ-9 score ≥20) and 60% (95% CI 50.56–70.58) for severe anxiety (GAD-7 score ≥15) (see also Fig. 1).

The findings from multivariate regression analysis on the characteristics associated with not accessing care for respondents reporting mental health problems in the previous 12 months and also screened positive with mental disorder symptoms are given in Table 4. The adjusted results show the influence of a poor household economic situation on not accessing care. Those with less severe depression were also less likely to access care. Gender, age and severity of anxiety showed no significant associations with not accessing care.

Table 4.

Results of multivariate regression analysis on characteristics associated with not utilising care for respondents reporting mental health problems in the previous 12 months and also screened with mental disorder symptoms (N = 520)

| Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Gender | ||

| Men | Ref | |

| Women | 0.82 (0.48–1.39) | 0.46 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–30 | Ref | |

| 31–44 | 1.19 (0.57–2.48) | 0.65 |

| 45–59 | 0.82 (0.40–1.71) | 0.60 |

| 60–74 | 0.74 (0.34–1.61) | 0.45 |

| ≥75 | 0.80 (0.31–2.08) | 0.64 |

| Household economic situation | ||

| Good/average | Ref | |

| Bad | 2.06 (1.20–3.54) | 0.01 |

| Very bad | 1.95 (1.03–3.67) | 0.04 |

| Depressiona | ||

| Severe | Ref | |

| Moderately severe | 2.77 (1.22–6.31) | 0.02 |

| Moderate | 4.61 (1.97–10.78) | 0.00 |

| Mild | 4.41 (1.78–10.94) | 0.00 |

| Anxietyb | ||

| Severe | Ref | |

| Moderate | 0.70 (0.36–1.38) | 0.30 |

| Mild | 0.83 (0.40–1.73) | 0.62 |

OR, Odds Ratio (adjusted); CI (Confidence Interval).

Data in bold are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

PHQ-9 score.

GAD-7.

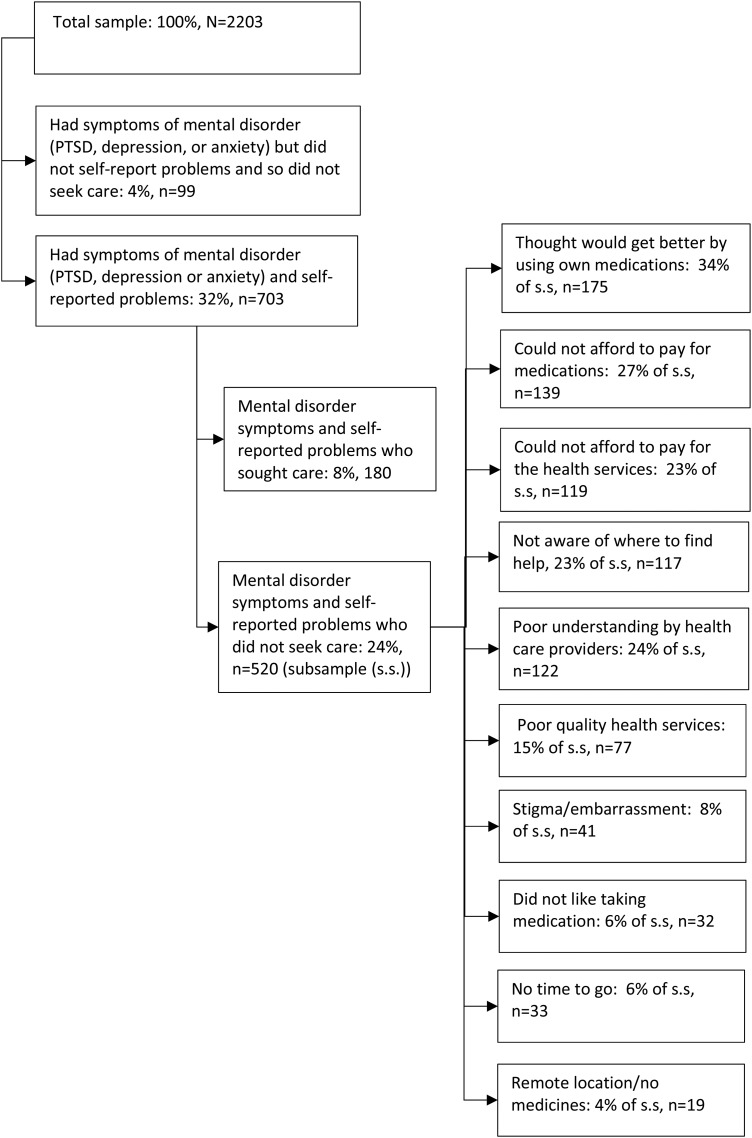

Of the 520 people who did not seek care despite self-reporting a mental health or emotional problem and being screened positive with PTSD, depression or anxiety, the most common reasons for not seeking care were: thought that they would get better by using their own medications (N = 176), could not afford to pay for medications (N = 140) or health services (N = 118), not aware of where they could find help (N = 118), poor understanding by health care providers (N = 123), poor quality of services (N = 78) and stigma/embarrassment (N = 41). See also Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Reasons of not seeking health care in the presence of mental health symptoms (multiple answers allowed).

Discussion

This study shows that among those likely to require some kind of MHPSS care (screened positive with at least one of the three disorders, and also self-reporting a problem) there was a treatment gap of 74%. Key reasons for not seeking care were using their own medications, could not afford to pay for health services or medications, no awareness of where to receive help, poor understanding by health care providers, poor quality of services, and stigma/embarrassment. The high treatment reflects the treatment gap observed globally (Kohn et al. 2004; WHO, 2010). Among non-conflict-affected persons in the WHO Europe region, the treatment gap varies from 45% for people with major depression to 62% for people with anxiety (Kohn et al. 2004; WHO, 2010). The closest direct comparison is with a study of IDPs in Georgia which used similar methods and definition of treatment gap and which showed a smaller treatment gap of 61% for people with symptoms of one or more disorders (PTSD, depression or anxiety) (Chikovani et al. 2015). Other studies with conflict-affected populations include a study conducted 8 years after the war in Kosovo, which found that 72% of people had used medical services in the past 12 months (Eytan & Gex-Fabry, 2012). Another study from Kosovo among female civilians 10 years after the war found that more than half used health care services during the previous 3 months but only a small minority used specialist mental health services (Morina & Emmelkamp, 2012). A study of war-affected populations from the Balkans observed general service use rates of between 61 to 94% and psychiatric service use ranged between 1.9 to 20.9% (Sabes-Figuera et al. 2012). However, direct comparison with these three studies is challenging due to different recall periods, methodologies and definitions. It is not possible to directly compare the treatment gap between IDPs and the rest of the Ukrainian population as the only other study on the treatment gap in Ukraine (from the 2001–2003 World Mental Health Survey) used a different methodology and definition, which followed narrower criteria, which led to an even higher treatment gap of around 83% (Demyttenaere et al. 2004).

The high treatment gap among IDPs and the barriers to care reported in our study reflect wider challenges with the provision and availability of MHPSS services in Ukraine and the health system more broadly. This includes low government spending on mental health, with only around 2.5% of total health expenditure allocated to mental health (compared with around 5% in neighbouring Poland) (Lekhan et al. 2015). The mental health system in Ukraine is also challenged by the ongoing reliance on centralised care through large psychiatric hospitals with often very poor conditions, rather than the globally recommended decentralisation of mental health care through the primary care system (WHO, 2010; Lekhan et al. 2015). Access to care is further hampered by insufficient and unequally distributed use of psychologists and psychotherapists, and the virtual absence of social workers in the system, particularly in clinical care settings (Pinchuk et al. 2013; Lekhan et al. 2015).

In addition, the costs of medications and care in Ukraine can be high. In our study, the average cost for the 44% of respondents that had paid for care was US$107 over the previous 12 months, while all respondents paid for medicines and the average cost for medicines over the previous 12 months was US$109. To put this in context, the average wage in Ukraine during that 12-month period was US$193. The negative influence of a bad household economic situation on health care utilisation further highlights the financial barriers faced by respondents in accessing MHPSS care. Given that few respondents used private providers, it appears that informal payments within the government services were common among respondents, reflecting such patterns in health service provision generally in Ukraine (Bazylevych, 2009; Footman et al. 2014; KIIS, 2015; Lekhan et al. 2015; Stepurko et al. 2015). Officially, Ukraine has a comprehensive guaranteed package of health care services provided free of charge at the point of use as a constitutional right; and, in theory, vulnerable groups and inpatients should be covered by public provision, but in practice they are often obliged to pay for their care (Lekhan et al. 2015). For historical reasons, outpatient medicines are not generally included in the state guaranteed package of benefits and the prices of pharmaceuticals in Ukraine are high by international standards; this has caused a substantial treatment gap with many patients forgoing medicines (Footman et al. 2014; Richardson et al. 2015).

Problems in accessing medicines are exacerbated by the lack of a national system for supplying medication to mental health patients, which increases the burden for the patients and their families, reduces access to treatment, and hampers compliance (Murphy et al. 2013; Lekhan et al. 2015; Zaprutko et al. 2015). Other studies in Ukraine have also highlighted the economic burden on patients with chronic conditions due to out-of-pocket payments (Murphy et al. 2013).

The study findings also highlight the heavy reliance on using pharmacies, with almost half of the respondents with current symptoms of a mental disorder using pharmacies and 17% using only a pharmacy without consulting a health professional. Such practice can be referred to as self-treatment because the pharmacist is not formally authorised to dispense medications for mental conditions without a prescription.

In our study, 10% of those who screened with a current mental disorder symptom did not recognise or acknowledge having a problem requiring professional help. While this is lower than observed with IDPs in Georgia (Chikovani et al. 2015), it nevertheless suggests there is a need to raise awareness and knowledge on mental health among IDPs in Ukraine given the evidence on how poor mental health knowledge negatively influences decisions about mental health treatment (ten Have et al. 2010; Rusch et al. 2011).

Given the high levels of mental disorders and limited utilisation of MHPSS care, IDPs should be considered a priority group for MHPSS care by relevant government agencies in Ukraine. Scaled-up, comprehensive and trauma-informed responses are needed for the provision of adequate MHPSS care for IDPs in Ukraine. These activities will require that health and social service providers should be trained in managing PTSD and common mental disorders, particularly family and district doctors, neurologists at polyclinics and general hospitals, alongside mental health specialists and social workers visiting communities. These responses also need to be part of wider health system strengthening reforms to improve access to MHPSS for the whole population.

Importantly, the strong negative influence of poverty on mental health and access to services should be recognised and addressed, including ensuring that national policies on free care and medicines are adhered to and ways of reducing financial barriers to mental health care addressed (Patel & Kleinman, 2003; Murali & Oyebode, 2004; Knapp et al. 2006; Saxena et al. 2007). More health promotion activities on the consequences of traumatic exposures and experiences should be developed and disseminated with an aim to educate populations on mental health symptoms and disorders, self-care, effects of self-medication, stigma, sources of services and support, and to increase demand and utilisation of services.

Limitations

We used screening instruments for mental disorders and so present data on symptoms of mental health disorders rather than diagnosed mental disorders case. In addition, the presence of symptoms of a mental disorder may not, in fact, indicate a need for care because those with milder conditions could remit without treatment (Demyttenaere et al. 2004; IASC, 2007). A more in-depth diagnostic interview would be preferable to gauge a more accurate treatment gap, but this was outside the scope and resources of the study. However, these measures have proven validity for measuring mental health needs (see above), with symptom severity indicative of mental health needs and poor overall functioning (Kroenke et al. 2001; Spitzer et al. 2006; Makhashvili et al. 2014; Blevins et al. 2015; Lahiri et al. 2016). We also could not determine whether the treatment received was effective (therefore potentially under-estimating the reported treatment gap for effective care). The distinction between different categories of services may also have not been obvious to participants (although clarification was provided to participants if requested). The study did not investigate participants’ perceptions on the quality of care or the care pathways. The data on costs of care and medicines were not linked to specific treatment or prescription/consumption patterns and so we could not determine the time-period the costs covered. The respondent numbers on costs incurred were also fairly small (particularly for the sub-group analysis by disorder type) and so are not generalisable. The period of mental disorder symptoms (within the past 1 or 2 weeks) differed from the period for the question on utilising health care for emotional and behavioural problems (1 year) which could increase recall bias. Another limitation was that we did not perform inter-rater reliability test for the data collectors. The study instruments were also not developed specifically for the study population and so may be prone to lack of cultural validity. However, they did go through a rigorous translation, adaption and piloting process, and the psychometric properties of the instruments were also tested and shown to be good (see above). We could also not explore how PTSD severity influenced the findings as the PCL-5 uses only a cut-off for screening with/without PTSD and does not use additional cut-offs for levels of PTSD severity and we were reluctant to arbitrarily impose cut-offs for PTSD severity due to validity concerns, particularly sensitivity and specificity. Last, the study did not include the estimated 5 million people still living in the conflict-affected area in the Donbas region and it is quite likely they will have considerable mental health needs given the daily stressors they are facing and their limited access to mental health services.

Conclusions

This study provides the first nationally representative data on the mental health of adult IDPs in Ukraine. The study shows that around three quarters of IDPs who require mental health care did not receive it. Key reasons for not seeking care were not being aware of the need for care, self-medicating, the high costs of treatment and medicines, and poor quality of existing care. Scaled-up, comprehensive and trauma informed responses are needed for the provision of MHPSS care of IDPs in Ukraine.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the IDP respondents in this study.

Financial support

This study was funded through a grant from the European Union the EU Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP) under the Project: Psychosocial seeds for peace: trauma rehabilitation and civic activism in Ukraine, implemented by International Alert (UK).

Conflict of interest

None.

Availability of Data and Materials

Further information on the data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from bayard.roberts@lshtm.ac.uk

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796017000385.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- Bazylevych M (2009). Who is responsible for our health? Changing concepts of the state and the individual in post-Soviet Ukraine. Anthropology of East Europe Review 27, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet K, Ramesh A, Frison S,Warren E, Hossain M, Smith J, Knight A, Post N, Lewis C, Woodward A, Dahab M, Ruby A, Sistenich V, Pantuliano S, Roberts B (2017). A review of evidence on public health interventions in humanitarian crises. Lancet June, 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress 28, 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikovani I, Makhashvili N, Gotsadze G, Patel V, McKee M, Uchaneishvili M, Rukhadze N, Roberts B (2015). Health service utilization for mental, behavioural and emotional problems among conflict-affected population in Georgia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 10, e0122673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JT, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M (2003). Common mental disorders in postconflict settings. Lancet 361, 2128–2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, de Girolamo G, Morosini P, Polidori G, Kikkawa T, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Takeshima T, Uda H, Karam EG, Fayyad JA, Karam AN, Mneimneh ZN, Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, de Graaf R, Ormel J, Gureje O, Shen Y, Huang Y, Zhang M, Alonso J, Haro JM, Vilagut G, Bromet EJ, Gluzman S, Webb C, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Anthony JC, Von Korff MR, Wang PS, Brugha TS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Lee S, Heeringa S, Pennell BE, Zaslavsky AM, Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Consortium WH O. W. M. H. S. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291, 2581–2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng F (1998). Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. United Nations: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Exchange Rates site (2017). US Dollar (USD) to Ukraine Hryvnia (UAH) exchange rate history.

- Eytan A, Gex-Fabry M (2012). Use of healthcare services 8 years after the war in Kosovo: role of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. European Journal of Public Health 22, 638–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher Raymond H, Ick T, Grasso M, Vaudrey J, McFarland W (2007). Resource Guide: Time Location Sampling (TLS). San Francisco Department of Public Health: San Francisco. [Google Scholar]

- Footman K, Richardson E, Roberts B, Alimbekova G, Pachulia M, Rotman D, Gasparishvili A, McKee M (2014). Foregoing medicines in the former Soviet Union: changes between 2001 and 2010. Health Policy 118, 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IASC (2007). IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. IASC: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- KIIS (2015). Analytical Report: Corruption in Ukraine: Comparative Analysis of National Surveys: 2007, 2009, 2011, and 2015. Kiev International Institute of Sociology: Kiev. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp M, Funk M, Curran C, Prince M, Grigg M, McDaid D (2006). Economic barriers to better mental health practice and policy. Health Policy and Planning 21, 157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B (2004). The treatment gap in mental health care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82, 858–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16, 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri S, van Ommeren M, Roberts B (2016). The influence of humanitarian crises on social functioning among civilians in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Glob Public Health, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekhan V, Rudiy V, Shevchenko M, Nitzan Kaluski D, Richardson E (2015). Ukraine: health system review. Health Systems in Transition 17, 1–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhashvili N, Chikovani I, McKee M, Bisson J, Patel V, Roberts B (2014). Mental disorders and their association with disability among internally displaced persons and returnees in Georgia. Journal of Trauma Stress 27, 509–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Rasmussen A (2009). War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science and Medicine 70, 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morina N, Emmelkamp PM (2012). Health care utilization, somatic and mental health distress, and well-being among widowed and non-widowed female survivors of war. BMC Psychiatry 12, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murali V, Oyebode F (2004). Poverty, social inequality and mental health. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 10, 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A, Mahal A, Richardson E, Moran AE (2013). The economic burden of chronic disease care faced by households in Ukraine: a cross-sectional matching study of angina patients. International Journal for Equity in Health 12, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Kleinman A (2003). Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81, 609–615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinchuk IY (2013). The dynamics of mental health in the Ukrainian population from 2008 to 2012 and prospects for the development of mental health care services in the country. Archives of Psychiatry 72, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Porter M, Haslam N (2005). Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a meta-analysis. JAMA 294, 602–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson E, Sautenkova N, Bolokhovets G (2015). Access to pharmaceuticals in the former Soviet Union. Eurohealth 21, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rusch N, Evans-Lacko SE, Henderson C, Flach C, Thornicroft G (2011). Knowledge and attitudes as predictors of intentions to seek help for and disclose a mental illness. Psychiatric Services 62, 675–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabes-Figuera R, McCrone P, Bogic M, Ajdukovic D, Franciskovic T, Colombini N, Kucukalic A, Lecic-Tosevski D, Morina N, Popovski M, Schutzwohl M, Priebe S (2012). Long-term impact of war on healthcare costs: an eight-country study. PLoS ONE 7, e29603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H (2007). Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 370, 878–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine 166, 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State Employment Service (2016). Policy Brief: The information of Providing Services to IDPs (In Ukrainian). State Employment Service: Kiev. [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, Marnane C, Bryant RA, van Ommeren M (2009). Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 302, 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepurko T, Pavlova M, Gryga I, Murauskiene L, Groot W (2015). Informal payments for healthcare services in Lithuania and Ukraine In Informal Economies in Post-Socialist Spaces: Practices, Institutions and Networks (ed. Morris J and Polese A), pp. 195–223. Palgrave Macmillan: London. [Google Scholar]

- Summers A, Leidman E, Bilukha O (2016). Health and Nutrition Assessment of Older Persons – Donetsk and Luhansk, Ukraine. UNICEF/US CDC: Kiev. [Google Scholar]

- ten Have M, de Graaf R, Ormel J, Vilagut G, Kovess V, Alonso J (2010). Are attitudes towards mental health help-seeking associated with service use? results from the European study of epidemiology of mental disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 45, 153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyldum G, Johnston LG (eds) (2014). Applying Respondent Driven Sampling to Migrant Populations. Palgrave: London. [Google Scholar]

- UNOCHA (2015). Humanitarian Needs Overview – Ukraine. UNOCHA: Geneva/Kiev. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ommeren M, Sharma B, Thapa S, Makaju R, Prasain D, Bhattarai R, De Jong J (1999). Preparing instruments for transcultural research: use of the translation monitoring form with Nepali-speaking Bhutanese refugees. Transcultural Psychiatry 36, 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2010). mhGAP Intervention Guide for Mental, Neurological and Substance use Disorders in Non-specialized Health Settings. World Health Organization: Geneva. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2013). Guidelines for the Management of Conditions Specifically Related to Stress. World Health Organization: Geneva. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO & UNHCR (2012). Assessing Mental Health and Psychosocial Needs and Resources: Toolkit for Major Humanitarian Settings. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Zaprutko T, Nowakowska E, Kus K, Bilobryvka R, Rakhman L, Poglodzinski A (2015). The cost of inpatient care of schizophrenia in the Polish and Ukrainian academic centers–Poznan and Lviv. Academic Psychiatry 39, 165–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796017000385.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Further information on the data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from bayard.roberts@lshtm.ac.uk