Abstract

Aims.

Mental health stigma and discrimination are significant problems. Common coping orientations include: concealing mental health problems, challenging others and educating others. We describe the use of common stigma coping orientations and explain variations within a sample of English mental health service users.

Methods.

Cross-sectional survey data were collected as part of the Viewpoint survey of mental health service users’ experiences of discrimination (n = 3005). Linear regression analyses were carried out to identify factors associated with the three stigma coping orientations.

Results.

The most common coping orientation was to conceal mental health problems (73%), which was strongly associated with anticipated discrimination. Only 51% ever challenged others because of discriminating behaviour, this being related to experienced discrimination, but also to higher confidence to tackle stigma.

Conclusions.

Although stigma coping orientations vary by context, individuals often choose to conceal problems, which is associated with greater anticipated and experienced discrimination and less confidence to challenge stigma. The direction of this association requires further investigation.

Key words: Discrimination, mental illness stigma, stereotypes, stress

Background

Experiences of discrimination are common among people with mental health problems (Brohan et al. 2013; Corker et al. 2013; Henderson et al. 2014; Lasalvia et al. 2015). Moreover, stigma and discrimination represent important factors, which can impede help-seeking (Lewer et al. 2015) and recovery (Livingston & Boyd, 2010). Stigma and discrimination experienced by people with mental health problems can be considered within a stress and coping framework, with the stressor being a threat to social identity (Major & O'Brien, 2005). There are three coping orientations within the stigma-coping-framework by Link et al. (1991, 2002) that are commonly described in the literature: (1) secrecy (concealing mental illness), (2) educating others about mental illness and (3) challenging others about their stigmatising attitudes and behaviours.

Coping with stigma can help to maintain a positive self-concept (Major & O'Brien, 2005) and self-esteem (Ilic et al. 2011). But, depending on the coping strategy, outcomes may differ substantially. The literature suggests that secrecy is associated with lower self-esteem (Ilic et al. 2011), higher levels of experienced discrimination (Lasalvia et al. 2013) and perceived discrimination as well as self-stigma (Vauth et al. 2007). In contrast, active strategies like educating others and challenging others were not associated with less self-esteem or feeling ashamed (Link et al. 2002), and there was no effect on self-stigma (Moses, 2014) or on devaluation and discrimination (Link et al. 1991). Overall, there is only little evidence about positive and negative correlates of different coping orientations. In addition to anticipated and experienced stigma and discrimination, clinical and socio-demographic characteristics such as diagnosis (Brohan et al. 2011) and gender may be associated with variation in use of coping orientations (Rusch et al. 2011). Still, findings are contradictory and scarce, particularly for socio-demographic variables such as age, ethnicity and education (Ilic et al. 2011; Rüsch et al. 2011; Moses, 2014).

Aims

Our study describes the occurrence and pattern of use of three common stigma coping orientations (Link et al. 1991, 2002): (1) concealing mental health problems (=secrecy), (2) educating others and (3) challenging others among a sample of 3005 English mental health service users. Further, we describe associations of these coping orientations with anticipated and experienced discrimination, social capital and overall confidence and ability to use personal skills in coping with stigma and discrimination.

Method

Study design

This study uses data from the Viewpoint survey of mental health service users’ experiences of discrimination in England, collected between 2011 and 2013. Full methodological details and results have been reported elsewhere (Corker et al. 2013). The study team conducted telephone interviews among a different sample each year. Participants were recruited through National Health Service (NHS) Mental Health trusts (service provider organisations). Participants were eligible to take part if they were aged 18–65, had any mental health diagnosis (excluding dementia) and had been in recent receipt of specialist mental health services (contact during the previous 6 months). Participants were excluded if they were not currently living in the community (e.g., in prison or hospital) since participants needed to be available to take part in a sensitive, confidential telephone survey.

In each year, five different NHS mental health trusts across England were selected to take part (n = 15). Trusts were intended to be representative of NHS mental health organisations in England, based on the socio-economic deprivation level of their catchment area. The study received approval from Riverside NHS Ethics Committee 07/H0706/72.

Participants

Within each participating trust, non-clinical staff in information technology or patient records departments used their central patient database to select a random sample of persons receiving care for ongoing mental health problems. Up to 4000 invitation packs were sent out from each participating trust to achieve a sample size of approximately 1000 service users each year.

Invitation packs contained complete information about the study including lists of interview topics, local and national sources of support, and a consent form. Information was also included in 13 commonly spoken languages explaining how to obtain the information pack in another language if needed. A reminder letter was mailed to non-responders after 2 weeks. Participants mailed written consent forms, including contact details, directly to the research team. Participants were offered a £10 voucher for taking part in the survey. All telephone interviewers were trained and supervised by the research team. Data collection was carried out by trained and supervised interviewers, the majority of whom had experience of mental health problems themselves. Consent was confirmed verbally by the interviewer prior to start of the interview. The current study comprises the samples of 2011, 2012 and 2013 with a total of 3005 participants.

Measures

Experienced and anticipated discrimination

The Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC) was used to measure experienced discrimination and anticipated discrimination. The DISC is interviewer administered and has demonstrated good reliability, validity and acceptability (Thornicroft et al. 2009; Brohan et al. 2013). Experienced discrimination is assessed via 22 items, covering 21 specific life areas, plus an additional item to record ‘other’ experiences. Anticipated discrimination is measured with four items, three items asking about life areas where discrimination was anticipated and one item asking about concealing mental health problems. Overall experienced discrimination scores were calculated by counting any reported instance of negative discrimination as ‘1’ and situations in which no discrimination was reported as ‘0’. The overall score was then calculated as: sum of reported discrimination divided by the number of questions answered (only applicable answers were included) and multiplied by 100. This provides a percentage of items in which discrimination was reported. For example, if a participant reported discrimination for 13 out of the possible 22 items and also reported that four items were not applicable, then the overall score would be 3/(22–4) × 100 = 72%.

Confidence and ability to tackle stigmatisation

The final section of the DISC-12 contains one item about the ability to deal with discrimination and stigma encountered because of mental illness. In addition, one question about participants’ overall confidence in tackling stigma and discrimination was included in the survey.

Social capital

The Resource Generator-UK (RG-UK) (Webber & Huxley, 2007) was used to measure participants’ access to social resources within their own social network (‘social capital’). The instrument has four subscales each representing a concrete domain of social capital: domestic resources, personal skills, expert advice and problem-solving resources. The RG-UK has good reliability and validity (Webber & Huxley, 2007) and has been used in samples of people with mental health problems (Webber et al. 2014) and produced valid findings. RG-UK total and subscale scores were calculated by scoring items accessible within a participant's network as 1 and those not accessible as 0, and then summing to calculate scale totals. Missing values of RG-UK items were replaced using multiple imputation (Sterne et al. 2009).

Stigma coping

We assessed three types of stigma coping orientations: educating others, challenging others and concealing mental health problems. Educating others and challenging others were assessed via two subscales of the revised Stigma Coping Scale (Link et al. 2004). The educating others subscale consists of three items assessing how much mental health service users educate others about their condition or about mental illness in general. Responses are given on a four-point scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ within the context of the previous 3 months; Cronbach's alpha is 0.71. The stigma coping orientation challenging others is measured using five items assessing how much mental health service users challenge stigmatising behaviour of others within the context of the previous 3 months. Response options are on a five-point scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘very often’ Cronbach's alpha is 0.75. As a proxy for the coping orientation secrecy the DISC-item asking about concealing mental health problems (terms are used interchangeably) was used, with response options on a four-point scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘a lot’ within the context of the previous 12 months.

Statistical analysis

In order to characterise coping orientations, we first created binary variables, categorising participants who reported any v. no use of the three coping orientations. Cut points were identified, which captured the natural distribution of the sample data. Neither concealing mental health problems nor challenging others were normally distributed as both had a substantial percentage of people not applying the coping orientation at all. Thus, concealing mental health problems was dichotomised as ‘not at all’ v. ‘a little’, ‘sometimes’, ‘fairly often’ and ‘very often’. Educating others had a normal distribution and therefore was dichotomised as ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘disagree’ – v. ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’. Challenging others was dichotomised as ‘never’ v. ‘almost never’, ‘sometimes’, ‘fairly often’ and ‘very often’. As some individuals used multiple coping orientations, we also investigated the pattern of use (i.e., exclusive use or multiple use of coping orientations) for each of the three coping orientation styles challenging others, educating others and secrecy for the full sample and stratified by gender in order to describe gender differences in the use of coping orientations. Coping orientations of males v. females were compared using chi-squared statistic.

Unadjusted and fully adjusted linear regression analyses were carried out in order to identify factors associated with the three stigma coping orientations (challenging, educating and concealment). We calculated standardised mean values for each of the stigma coping orientation outcomes based on z-score. Thus, the outcomes reflect the frequency and/or intensity that each strategy was employed. Independent variables were: socio-demographic characteristics including age, gender, ethnicity, education and employment, and clinical characteristics including first contact with mental health services, involuntary admission, and diagnosis (depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorder, schizoaffective disorder and other). Further, experienced and anticipated discrimination, social capital and the ability and confidence to cope with stigma were independent variables. Regression diagnostics were carried out for each model, the data did not have significant outliers, and the statistical assumptions of collinearity, normality, homogeneity of variance and linearity were met. Analyses were carried out using SPSS for Mac, release 22.

Results

Participant characteristics

Overall, 3005 participants were included in our analysis. Response rates for completed interviews were 11% in 2011, 10% in 2012 and 10% in 2013, respectively. Female (61.1%) and white (89.5%) British participants were over-represented in our sample. Half of the participants were unemployed (51.4%) and depression was the most common diagnosis (27.7%) followed by bipolar disorder (19.4%) and schizophrenia (14%). For details of participant characteristics see Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

| Demographic characteristic | Participants (n = 3005) n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 1163 (38.7) |

| Female | 1835 (61.1) |

| Transgender | 6 (0.2) |

| Age (years) Mean (s.d.) | 45 (11.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 2688 (89.5) |

| Black or Mixed Black and White | 145 (4.8) |

| Asian or Mixed Asian and White | 124 (4.1) |

| Other | 34 (1.1) |

| Unanswered | 14 (0.5) |

| Education | |

| Professional training | 167 (5.6) |

| University – post graduate | 315 (10.5) |

| University – undergraduate | 580 (19.3) |

| College/school A-levels/equivalent | 812 (27.0) |

| School – O-level/GCSE/equivalent | 913 (30.4) |

| Other | 189 (6.3) |

| Unanswered | 29 (1.0) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 1545 (51.4) |

| Part-time employed | 292 (9.7) |

| Full-time employed | 301 (10) |

| Self-employed | 75 (2.5) |

| Retired | 234 (7.8) |

| Volunteering | 161 (5.4) |

| Training/education | 109 (3.6) |

| Other | 285 (9.5) |

| Unanswered | 2 (0.1) |

| Main diagnosis | |

| Depression | 833 (27.7) |

| Bipolar disorder | 583 (19.4) |

| Schizophrenia | 421 (14.0) |

| Anxiety disorder | 298 (9.9) |

| Personality disorder | 224 (7.5) |

| Eating disorder | 41 (1.4) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 79 (2.6) |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 10 (0.3) |

| Substance misuse/addiction | 3 (0.1) |

| Multiple diagnoses | 57 (1.9) |

| Other | 197 (6.6) |

| Unanswered | 5 (0.2) |

| Received involuntary treatment | |

| Yes | 1120 (37.3) |

| No | 1879 (62.5) |

| Unanswered | 6 (0.2) |

| Have you been able to use your personal skills or abilities in coping with stigma? | |

| Yes | 2024 (67.4) |

| No | 730 (24.3) |

| Not applicable | 215 (7.2) |

| Compared with a year ago I feel I have more confidence to challenge mental health stigma and discrimination when I see it | |

| Yes | 1796 (59.8) |

| No | 1191 (39.6) |

| Resource generator UK | Mean (s.d.) |

| Total score | 13.35 (5.99) |

| Domestic score | 3.86 (1.99) |

| Expert score | 4.05 (2.38) |

| Skills score | 2.63 (1.64) |

| Problem solving score | 2.80 (1.27) |

Prevalence of type of stigma coping orientation

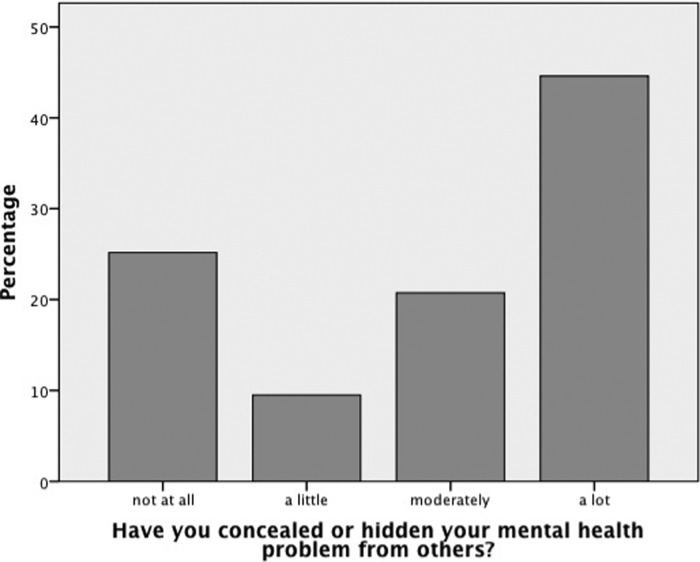

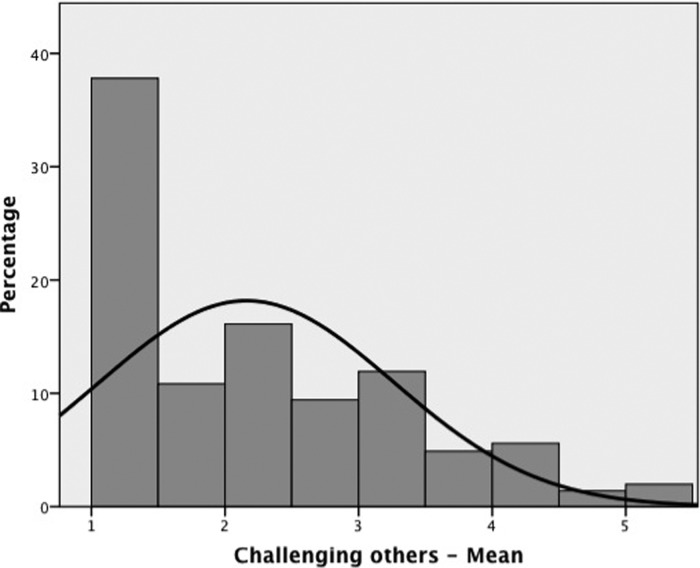

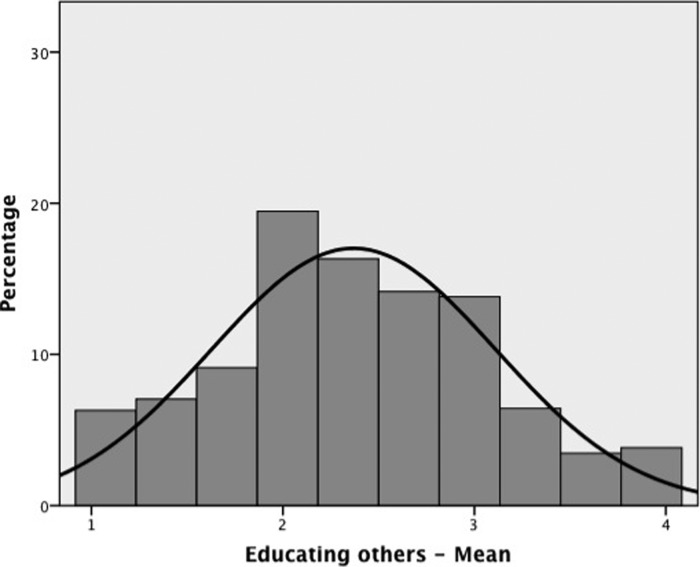

The most common coping orientation concealing mental health problems was used by 73% of mental health service users. The distribution of responses was left skewed with 44% reporting using this orientation ‘a lot’, 20% ‘moderately’ and 9% ‘a little’. Only 25% reported not concealing mental health problems at all (see Fig. 1). Challenging others about their stigmatising attitudes to mental illness was reported by 51% of respondents while almost half (49%) ‘never’ challenged others (see Fig. 2). For educating others, 43% of participants ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that they were applying this coping orientation. The use of this coping orientation was normally distributed (see Fig. 3). As all three coping orientations were rated simultaneously, the frequencies of their use do not add up to 100%.

Fig. 1.

The DISC-item was used as a proxy for the coping orientation secrecy. Answer options range from 1= not at all to 4 = a lot.

Fig. 2.

Item example: ‘How often did you let someone know that their behaviour was stigmatising?’ Answer options range from 1 = never to 5 = very often.

Fig. 3.

Item example: ‘After you entered mental health services, you found yourself educating others about what it means to be a mental health service user’; answer options range from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree.

Pattern of coping orientation

Only a minority of participants (19%) used one stigma coping orientation alone. Combining multiple coping orientations was common, with the majority of people (44%) applying two and about a third applying all three orientations (31.6%). Significant gender differences were found with women being more likely than men to combine conceal and challenging and conceal, educating and challenging. Men were more likely than women to use educating others as well as a combination of educating and challenging (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Reported patterns of stigma coping orientations (n = 3005)

| Total sample n (%) | Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Fisher's exact test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigma coping orientation | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Gender diff. |

| Conceal only (‘not at all’ v. ‘a little – a lot’) | 173 (5.8) | 2766 (92.0) | 74 (6.4) | 1056 (90.8) | 99 (5.4) | 1704 (92.9) | p = 0.135 |

| Educating only (strongly disagree/disagree v. agree/strongly agree) | 158 (5.3) | 2818 (93.8) | 94 (8.1) | 1055 (90.7) | 64 (3.5) | 1756 (95.7) | p < 0.001 (m > f) |

| Challenging only (‘never’ v. ‘almost never – very often’) | 245 (8.2) | 2719 (90.5) | 110 (9.5) | 1030 (88.6) | 133 (7.2) | 1685 (91.8) | p = 0.015a (m > f) |

| Conceal and educating | 354 (11.8) | 2588 (86.1) | 145 (13.2) | 978 (84.1) | 199 (10.8) | 1605 (87.5) | p = 0.022a (m > f) |

| Conceal and challenging | 721 (24.0) | 2201 (73.2) | 217 (18.7) | 902 (77.6) | 502 (27.4) | 1295 (70.6) | p < 0.001 (f > m) |

| Educating and challenging | 258 (8.6) | 2725 (90.7) | 122 (10.5) | 1027 (88.3) | 135 (7.4) | 1692 (92.2) | p = 0.002 (m > f) |

| Conceal, educating and challenging | 950 (31.6) | 1972 (65.5) | 320 (27.5) | 799 (68.7) | 630 (34.3) | 1167 (63.6) | p < 0.002 (f > m) |

Overall test significance, but standardised residual <1.96.

Differences in the stigma coping orientations by diagnosis

There were significant differences by diagnosis for concealing mental health problems (χ2 (6, n = 2686) = 48.6; p < 0.0001), challenging others (χ2 (6, n = 2727) = 43.9; p < 0.0001) and educating others (χ2 (6, n = 2738) = 13.3; p < 0.038). Mental health service users with a diagnosis of depression (p < 0.0001) and a diagnosis of personality disorder (p < 0.004) concealed their mental health problems significantly more, whereas those diagnosed with schizophrenia concealed less (p < 0.0001). Participants diagnosed with schizophrenia challenged others less for their discriminating behaviour than those with other diagnoses (p < 0.0001) but educated others more (p < 0.002) than other mental health service users.

Factors associated with different stigma coping orientations

The most important predictor for the coping orientation concealing mental health problems was the number of life areas in which discrimination was anticipated, with more anticipated discrimination being associated with a higher tendency to conceal mental health problems. Furthermore, concealment was significantly associated with higher experienced discrimination and having less confidence to challenge stigma. In relation to socio-demographic and clinical variables, concealing mental health problems was positively associated with being female, being from a White background (v. being from a Black or Asian background), holding a university degree, being employed or economically inactive (v. unemployed) and not having been admitted to hospital involuntarily. These factors overall explained 32% of the variance for concealing mental health problems. When predictors were removed blockwise from the regression model, only anticipated discrimination changed the adjusted R2 significantly, dropping from R2adj = 0.32 to R2adj = 0.10 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlates of ‘Conceal mental health problems’ in a multivariable linear regression analysis

| Variable | Unadjusted B (95% CI) | Adjusted B (95% CI) | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–24 (ref.) | – | – | – |

| 25–44 | −0.06 (−0.23, 0.11) | −0.04 (−0.18, 0.10) | −0.02 |

| 45–65 | −0.14 (−0.31, 0.02) | −0.03 (−0.17, 0.12) | −0.01 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | −0.26 (−0.33, −0.18)** | −0.15 (−0.22, −0.09)** | −0.08 |

| Female (ref.) | – | – | – |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Black | −0.18 (−0.35, −0.01)* | −0.25 (−0.42, −0.07)* | −0.04 |

| Asian | −0.21 (−0.39, −0.03)* | −0.30 (−0.55, −0.04)* | −0.04 |

| Other | −0.08 (−0.26, 0.42) | −0.09 (−0.23, 0.05) | −0.02 |

| White (ref.) | – | – | – |

| Highest education | |||

| University degree or professional training | 0.08 (0.008, 0.16)* | 0.002 (−0.05, 0.05) | 0.001 |

| No university degree or professional training (ref.) | – | – | – |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | −0.004 (−0.09, 0.08) | 0.13 (0.06, 0.21)** | 0.06 |

| Economically inactive | −0.06 (−0.16, 0.04) | 0.10 (0.016, 0.19)* | 0.04 |

| Unemployed (ref.) | – | – | – |

| Involuntary admission | |||

| Having been admitted | −0.18 (−0.26, −0.11)** | −0.12 (−0.18, −0.05)** | −0.06 |

| Not having been admitted (ref.) | – | – | – |

| Years since first contact with mental health services? | −0.001 (−0.004, 0.002) | 0.000 (−0.003, 0.003) | −0.001 |

| Number of life areas in which discrimination was anticipated | 0.44 (0.42, 0.47)** | 0.41 (0.39, 0.44)** | 0.52 |

| Experienced discrimination (DISC score) | 0.012 (0.01, 0.013)** | 0.003 (0.001, 0.004)** | 0.06 |

| Have you been able to use your personal skills or abilities in coping with stigma? | |||

| Yes | −0.004 (−0.09, 0.08) | 0.000 (−0.08, 0.07) | 0.000 |

| Not applicable | −0.33 (−0.48, −0.17)** | −0.01 (−0.15, 0.13) | −0.003 |

| No (ref.) | – | – | – |

| Confidence to challenge mental health stigma and discrimination | |||

| Yes | −0.18 (−0.26, −0.11)** | −0.09 (−0.15, −0.021)* | −0.04 |

| No (ref.) | – | – | – |

| Resource generator UK total score | −0.01 (−0.02, −0.004)** | −0.004 (−0.01, 0.001) | −0.03 |

| Model summary | R2adj = 0.32, F = 70.67, p < 0.001 | ||

Significance level: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

The main characteristic associated with using the stigma coping orientation challenging others was experienced discrimination: greater past experience of discrimination was associated with a stronger tendency to challenge others. Also, challenging discrimination was positively related to a higher number of life areas in which discrimination was anticipated. Higher social capital, as well as a stronger ability to cope with stigma and discrimination and more confidence to challenge stigma was significantly associated with a greater likelihood to challenging others.

Furthermore, challenging others was positively associated with female gender and not having been admitted to hospital involuntarily. Overall these factors explained 19% of the variance of the stigma coping orientation challenging others. After removing experienced discrimination from the regression model, the R2adj dropped to 0.09 and the removal of ‘resources’ (social capital, ability and confidence to cope with stigma) changed the R2adj to 0.11. Exclusion of other (socio-demographic variables and anticipated stigma) variables left the R2adj largely unaffected (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlates of ‘Challenging others’ in a multivariable linear regression analysis

| Variable | Unadjusted B (95% CI) | Adjusted B (95% CI) | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–24 (ref.) | – | – | |

| 25–44 | −0.19 (−0.36, −0.03)* | −0.16 (−0.31, −0.004)* | −0.08 |

| 45–65 | −0.26 (−0.42, −0.10)* | −0.07 (−0.23, 0.09) | −0.04 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | −0.22 (−0.30, −0.15) | −0.13 (−0.20, −0.06)** | −0.06 |

| Female (ref.) | – | – | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Black | −0.01 (−0.18, 0.16) | −0.11 (−0.30, 0.08) | −0.02 |

| Asian | −0.03 (−0.22, 0.15) | 0.08 (−0.19, 0.36) | 0.01 |

| Other | 0.39* (0.05, 0.73) | 0.08 (−0.08, 0.23) | 0.02 |

| White (ref.) | – | – | |

| Highest Education | |||

| University degree or professional training | −0.03 (−0.11, 0.04) | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.03) | −0.02 |

| No university degree or professional training (ref.) | – | – | |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | 0.067 (−0.01, 0.15) | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.10) | 0.006 |

| Economically inactive | −0.08 (−0.18, 0.02) | −0.02 (−0.11, 0.08) | −0.006 |

| Unemployed (ref.) | – | – | |

| Involuntary admission | |||

| Having been admitted | −0.10 (−0.17, −0.02)* | −0.10 (−0.17, −0.03)* | −0.05 |

| Not having been admitted (ref.) | – | – | |

| Years since first contact with mental health services? | −0.002 (−0.006, 0.001) | −0.002 (−0.006, 0.001) | −0.03 |

| Number of life areas in which discrimination was anticipated | 0.13 (0.10, 0.16)** | 0.03 (0.003, 0.06)* | 0.04 |

| Experienced discrimination (DISC score) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02)** | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02)** | 0.31 |

| Have you been able to use your personal skills or abilities in coping with stigma? | |||

| Yes | 0.29 (0.21, 0.38)** | 0.18 (0.10, 0.26)** | 0.08 |

| Not applicable | −0.43 (−0.58, −0.28)** | −0.21 (−0.36, −0.06)* | −0.05 |

| No (ref.) | – | – | |

| Confidence to challenge mental health stigma and discrimination | |||

| Yes | 0.43 (0.36, 0.50)** | 0.39 (0.32, 0.46)** | 0.19 |

| No (ref.) | – | – | |

| Resource generator UK total score | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03)** | 0.02 (0.01, 0.02)** | 0.10 |

| Model summary | R2adj = 0.19, F = 33.74, p < 0.001 | ||

Significance level: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

Although the regression model for the stigma coping orientation educating others was found to be significant, only 3.6% of the variance was explained by these variables. Educating others was significantly positively associated with anticipated discrimination, but negatively with experienced discrimination. Also, a higher tendency to educate others was associated with having been admitted to hospital involuntarily, less confidence to challenge stigma and lower social capital (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlates of ‘Educating others’ in a multivariable linear regression analysis

| Variable | Unadjusted B (95% CI) | Adjusted B (95% CI) | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | – | – | |

| 25–44 | −0.006 (−0.17, 0.16) | −0.02 (−0.19, 0.15) | −0.01 |

| 45–65 | −0.06 (−0.22, 0.11) | −0.13 (−0.31, 0.04) | −0.07 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 0.08 (0.007, 0.15) | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.13) | 0.03 |

| Female (ref.) | – | – | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Black | −0.09 (−0.26, 0.07) | −0.10 (−0.31, 0.11) | −0.02 |

| Asian | −0.10 (−0.29, 0.08) | −0.02 (−0.32, 0.28) | −0.002 |

| Other | 0.17 (−0.17, 0.51) | −0.13 (−0.30, 0.03) | −0.03 |

| White (ref.) | – | – | |

| Highest education | |||

| University degree or professional training | −0.12 (−0.20, −0.05) | −0.01 (−0.07, 0.05) | −0.01 |

| No university degree or professional training (ref.) | – | – | |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | −0.09 (−0.18, −0.01) | −0.001 (−0.09, 0.09) | 0.000 |

| Economically inactive | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.16) | 0.12 (0.01, 0.22)* | 0.04 |

| Unemployed (ref.) | – | – | |

| Involuntary admission | |||

| Having been admitted | 0.14 (0.07, 0.21) | 0.16 (0.08, 0.24)** | 0.08 |

| Not having been admitted (ref.) | – | – | |

| Years since first contact with mental health services? | 0.001 (−0.003, 0.004) | −0.001 (−0.004, 0.003) | −0.01 |

| Number of life areas in which discrimination was anticipated | 0.05 (0.02, 0.08) | 0.06 (0.03, 0.09)** | 0.07 |

| Experienced discrimination (DISC score) | 0.000 (−0.002, 0.001) | −0.002* (−0.004, −0.001) | −0.05 |

| Have you been able to use your personal skills or abilities in coping with stigma? | |||

| Yes | −0.09 (−0.17, −0.005)* | −0.008 (−0.10, 0.08) | −0.004 |

| Not applicable | 0.04 (−0.11, 0.20) | 0.11 (−0.06, 0.27) | 0.03 |

| No (ref.) | – | – | |

| Confidence to challenge mental health stigma and discrimination | |||

| Yes | −0.26 (−0.33, −0.18) | −0.23 (−0.31, −0.15)** | −0.11 |

| No (ref.) | – | – | |

| Resource generator UK total score | −0.02 (−0.02, −0.01) | −0.01 (−0.02, −0.003)* | −0.06 |

| Model summary | R2adj = 0.036, F = 6.19, p < 0.001 | ||

Significance level: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

Discussion

Overall, the most common type of stigma coping orientation was concealing mental health problems, followed by challenging others and lastly educating others. In relation to the pattern of use of coping orientations, 81% of mental health service users reported more than one coping orientation, which is consistent with stigma-coping research, suggesting that people may be flexible in how they use coping orientations, depending on the type of stigma and discrimination (Holmes & River, 1998) as well as the specific appraisals of the stressful events (Miller & Kaiser, 2001).

Concealing mental health problems

Although the most common and an understandable reaction to being devalued by the public, most of the available evidence suggests that there are mainly negative consequences associated with concealing mental health problems, such as lower self-esteem, higher self-stigma and higher experienced discrimination (Link et al. 1991; Ilic et al. 2011; Lasalvia et al. 2013). In line with this, we also found negative correlates such as higher anticipated and experienced stigma and discrimination, and less confidence to challenge stigma. In line with modified labelling theory (Link, 1989), the anticipation of stigma and discrimination – the strongest predictor in our regression model – is closely linked to ‘self-protection’ by keeping mental health problems a secret, more than actual experiences of discrimination. This is consistent with recent findings by Schibalski et al. (2017), showing that perceived stigma, that is correlated with anticipated stigma, predicted avoidant coping strategies. Consequently, this may lead to a loss of confidence to challenge stigma that, in turn, can enhance the anticipation and experience of stigma and discrimination and vice-versa (Vauth et al. 2007). Disclosing one's mental health problem, however, may not have only positive consequences. For example, although disclosure is associated with a reduction in stigma related stress (Rüsch et al. 2014), it may also increase the experience of stigma (Sarkin et al. 2015) and hence decrease self-esteem (Bos et al. 2009).

Challenging others

This coping orientation was most strongly associated with more experienced discrimination; but, at the same time participants also reported a better ability to cope with and greater confidence to challenge stigmatisation. This might be explained, on the one hand, by greater consciousness towards discrimination among people who challenge other's stigmatising thoughts and behaviour. On the other hand, those individuals might experience more discrimination and thus have more opportunities to challenge discrimination. Greater social capital was also associated with a higher likelihood of challenging other's stigmatising attitudes and behaviour – social resources might reduce psychological distress due to stigmatisation (Henderson et al. 2014; Webber et al. 2014). This relation might be also explained by more opportunities to challenge others when being part of a larger social network. Longitudinal studies need to be carried out for a better understanding of the direction of these relationships.

Educating others

Finally, educating others about their mental health problems was not associated with experienced discrimination, socio-demographic or clinical variables or with the confidence and ability to challenge stigma and only 3.6% of the variance was explained by our model. This finding is consistent with other studies reporting contradictory findings for educating others with less impact on various outcomes such as experienced discrimination and self-stigma (Link et al. 1991; Moses, 2014). Furthermore evidence from public anti-stigma campaigns suggests that improved public knowledge about people with mental illness does not necessarily increase empowerment among people with mental illness (Evans-Lacko et al. 2013).

Relationship of coping strategies with socio-demographic and clinical variables

We identified a significant relationship of diagnosis with use of different coping orientations. Secondary mental health service users with a diagnosis of depression or personality disorders concealed their mental health problems more than those with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and anxiety disorder. Those diagnosed with schizophrenia concealed less, and this is consistent with other findings noting higher disclosure rates among people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia compared with those with other diagnoses (Thornicroft et al. 2009). Individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia were also less likely to challenge others for their discriminating behaviour, but did educate others more about mental illness. For people with schizophrenia, it might be more difficult to hide symptoms and furthermore, they have a higher percentage of involuntary admissions compared with people with a diagnosis of depression (65 v. 20% in depression in our sample). In line with this, involuntary admissions themselves were independently associated with less secrecy and less challenging. On the other hand, the motivation to educate others about their illness might be higher in people who have less common diagnoses such as schizophrenia.

Gender was also a significant factor related to coping strategies. Being a woman was associated with a higher tendency to conceal mental health problems in the overall sample and more specifically in the subgroups of individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder or personality disorder. Although some studies suggest greater openness (Rüsch et al. 2011) and more help seeking behaviour among women (Holzinger et al. 2012), women also tend to report more experiences of discrimination and greater stigma associated with disclosure (Sarkin et al. 2015). At the same time, women challenged others more for their discriminating behaviour, consistent with previous findings from general stress research with women using more active strategies than men. Although significant associations of coping orientations with other socio-demographic variables (education, age) could be found, they were only weak predictors for the type or pattern of coping orientation used.

Implications for service users

The majority of mental health service users face stigma and discrimination (Thornicroft et al. 2009; Lasalvia et al. 2013; Corker et al. 2016). This study focused on how people respond to these life stressors, which are commonplace. Our data suggest that more active strategies are associated with positive effects and may lead to e.g., increased confidence to tackle stigma in contrast to secrecy. Those who conceal their mental health problems as a main coping strategy may experience greater fear of stigmatisation in education, work or in relationships. Self-stigma and anticipated public stigma might undermine efforts such as applying for a job or engaging in a relationship, also known as the ‘Why Try Effect’ (Corrigan & Rao, 2012). Interventions such as ‘Coming Out Proud’ (Corrigan et al. 2013) or decision aids for disclosure (Henderson et al. 2013) could help service users to develop more effective coping strategies and reduce stigma stress. Of course positive and negative consequences of different coping orientations have to be weighed out individually and depend on specific personal situations and the broader socio-cultural context in which the individual is living. A society, which is supportive and inclusive of people with mental health problems is a key factor for facilitating this virtuous cycle. More evidence is needed to specify the short and long term outcomes of different coping orientations.

Limitations and future directions

There are several limitations of our study, which could stimulate future stigma-coping-research. First of all, due to the cross-sectional nature of our study, we cannot draw conclusions about causality or the efficacy of stigma coping orientations. Also, due to a relatively low response rate (10%) the results may only be generalised with caution. The strength of this study is that it did not use a convenience sample and participants were randomly selected in contrast to other studies (Thornicroft et al. 2009; Brohan et al. 2011; Lasalvia et al. 2013). Furthermore, reported rates of anticipated and experienced discrimination are comparable to those reported in other surveys using different data collection methods (Thornicroft et al. 2009; Lasalvia et al. 2013). Additionally, the internal relationship between the coping strategy and other factors should remain valid.

Second, a proxy measure was used for the coping orientation concealing mental health problems. Consequently, the frequency of this coping orientation might be overestimated, as the item did not confine the use of concealing mental health problems to the last 3 months, as was the case for challenging and educating. Further, although secrecy is a coping orientation within Link's stigma coping framework, it should be acknowledged that it is rather a response to stigmatisation than an active coping strategy as challenging and educating others. Third, the DISC-12 does not measure stress appraisal and stress experience associated with reported instances of anticipated or experienced discrimination, which could be important moderating factors. Finally, specific discriminating events should be matched to the coping strategy applied in order to determine their effectiveness. Also, mediating variables like self-stigma, self-esteem and self-efficacy need to be included in longitudinal studies to further determine the direction of the associations between stigma and discrimination and different coping strategies.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

GT is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King's College London Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. GT acknowledges financial support from the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre and Dementia Unit awarded to South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King's College London and King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. GT is supported by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) Emerald project.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Availability of data and materials

We do not have ethical approval to share the data supporting the findings of our study.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S204579601700021X.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- Bos AER, Kanner D, Muris P, Janssen B, Mayer B (2009). Mental illness stigma and disclosure: consequences of coming out of the closet. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 30, 509–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Gauci D, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G (2011). Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with bipolar disorder or depression in 13 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Journal of Affective Disorders 129, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Clement S, Rose D, Sartorius N, Slade M, Thornicroft G (2013). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC). Psychiatry Research 208, 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corker E, Hamilton S, Henderson C, Weeks C, Pinfold V, Rose D, Williams P, Flach C, Gill V, Lewis-Holmes E, Thornicroft G (2013). Experiences of discrimination among people using mental health services in England 2008–2011. British Journal of Psychiatry 202 (Suppl. 55), s58–s63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corker E, Hamilton S, Robinson E, Cotney J, Pinfold V, Rose D, Thornicroft G, Henderson C (2016). Viewpoint survey of mental health service users’ experiences of discrimination in England 2008–2014. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 134 (Suppl. 446), 6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Rao D (2012). On the self-stigma of mental illness: stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 57, 464–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Kosyluk KA, Rüsch N (2013). Reducing self-stigma by coming out proud. American Journal of Public Health 103, 794–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko S, Malcolm E, West K, Rose D, London J, Rusch N, Little K, Henderson C, Thornicroft G (2013). Influence of Time to Change's social marketing interventions on stigma in England 2009–2011. British Journal of Psychiatry 202 (Suppl. 55), s77–s88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C, Brohan E, Clement S, Williams P, Lassman F, Schauman O, Dockery L, Farrelly S, Murray J, Murphy C, Slade M, Thornicroft G (2013). Decision aid on disclosure of mental health status to an employer: feasibility and outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 203, 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson RC, Corker E, Hamilton S, Williams P, Pinfold V, Rose D, Webber M, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G (2014). Viewpoint survey of mental health service users’ experiences of discrimination in England 2008–2012. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 49, 1599–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EP, River LP (1998). Individual strategies for coping with the stigma for severe mental illness. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 5, 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Holzinger A, Floris F, Schomerus G, Carta MG, Angermeyer MC (2012). Gender differences in public beliefs and attitudes about mental disorder in western countries: a systematic review of population studies. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 21, 73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic M, Reinecke J, Bohner G, Hans-Onno R, Beblo T, Driessen M, Frommberger U, Corrigan PW (2011). Protecting self-esteem from stigma: a test of different strategies for coping with the stigma of mental illness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 58, 246–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasalvia A, Zoppei S, Van Bortel T, Bonetto C, Cristofalo D, Wahlbeck K, Bacle SV, Van Audenhove C, van Weeghel J, Reneses B, Germanavicius A, Economou M, Lanfredi M, Ando S, Sartorius N, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Thornicroft G (2013). Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination reported by people with major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 381, 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasalvia A, Van Bortel T, Bonetto C, Jayaram G, van Weeghel J, Zoppei S, Knifton L, Quinn N, Wahlbeck K, Cristofalo D, Lanfredi M, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G (2015). Cross-national variations in reported discrimination among people treated for major depression worldwide: the ASPEN/INDIGO international study. British Journal of Psychiatry 207, 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewer D, O'Reilly C, Mojtabai R, Evans-Lacko S (2015). Antidepressant use in 27 European countries: associations with sociodemographic, cultural and economic factors. British Journal of Psychiatry 207, 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B (1989). A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. American Sociological Review 54, 400–423. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Mirotznik J, Cullen FT (1991). The effectiveness of stigma coping orientations: can negative consequences of mental illness labeling be avoided? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 32, 302–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC (2002). On describing and seeking to change the experience of stigma. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 6, 201–231. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, Collins PY (2004). Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30, 511–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, Boyd JE (2010). Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science and Medicine 71, 2150–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, O'Brien LT (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology 56, 393–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Kaiser CR (2001). A theoretical perspective on coping with stigma. Journal of Social Issues 57, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Moses T (2014). Coping strategies and self-stigma among adolescents discharged from psychiatric hospitalization: a 6-month follow-up study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Evans-Lacko SE, Henderson C, Flach C, Thornicroft G (2011). Knowledge and attitudes as predictors of intentions to seek help for and disclose a mental illness. Psychiatric Services 62, 675–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Abbruzzese E, Hagedorn E, Hartenhauer D, Kaufmann I, Curschellas J, Ventling S, Zuaboni G, Bridler R, Olschewski M, Kawohl W, Rossler W, Kleim B, Corrigan PW (2014). Efficacy of coming out proud to reduce stigma's impact among people with mental illness: pilot randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 204, 391–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkin A, Lale R, Sklar M, Center KC, Gilmer T, Fowler C, Heller R, Ojeda VD (2015). Stigma experienced by people using mental health services in San Diego County. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 50, 747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schibalski JV, Müller M, Ajdacic-Gross V, Vetter S, Rodgers S, Oexle N, Corrigan PW, Rössler W, Rüsch N (2017). Stigma-related stress, shame and avoidant coping reactions among members of the general population with elevated symptom levels. Comprehensive Psychiatry 74, 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, Wood AM, Carpenter JR (2009). Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. British Medical Journal 338, b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N, Leese M (2009). Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 373, 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauth R, Kleim B, Wirtz M, Corrigan PW (2007). Self-efficacy and empowerment as outcomes of self-stigmatizing and coping in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 150, 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber M, Corker E, Hamilton S, Weeks C, Pinfold V, Rose D, Thornicroft G, Henderson C (2014). Discrimination against people with severe mental illness and their access to social capital: findings from the Viewpoint survey. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 23, 155–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber MP, Huxley PJ (2007). Measuring access to social capital: the validity and reliability of the Resource Generator-UK and its association with common mental disorder. Social Science and Medicine 65, 481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S204579601700021X.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

We do not have ethical approval to share the data supporting the findings of our study.