Abstract

After the introduction of first generation MSNs for drug delivery with some challenges such as large particle sizes, irregular morphologies and aggregations, second generation provided uniform spherical morphologies, tunable pore/particle sizes and compositions. Henceforth, organic‐inorganic hybrid mesoporous silica nanosystems have grown rapidly and utilized for active and passive targeting of tumorigenic cells especially conjugated with organic polymers followed by third generation counterparts with improved functionalities for cancer therapy. The aim of this review article is to focus on the advancements in mesoporous silica based organic‐inorganic hybrid nanoparticles developed as drug carriers targeting cancer cells. Brief introduction to the state‐of‐the‐art in passive and active targeting methods is presented. Specifically, therapeutic, diagnostic and theranostic applications are discussed with emphases on triggered and ligand conjugated organic‐inorganic hybrid mesoporous silica nanomaterials. Although mesoporous silica nanoparticles perform well in preclinical tests, clinical translation progresses slowly as appropriate doses needs to be evaluated for human use along with biocompatibility and efficiency depending on surface modifications.

Keywords: Active targeting, Anticancer drug delivery, Diagnostic, Mesoporous silica nanoparticles, Theranostic

Abbreviations

- DOX

Doxorubicin

- GNPs

Gold nanoparticles

- GNRs

Gold nanorods

- GSH

Glutathione

- ICG

Indocyanine green

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- mSiO2

Mesoporous silica structures

- MSNs

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles

- NIR

Near‐Infrared

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

- P‐gp

P‐glycoprotein

- p(NIPAm)

poly(N‐isopropylacrylamide)

- PVP

Polyvinylpyrrolidone

1. Introduction

The inorganic nanoparticles such as quantum dots (QDs), gold nanoparticles (GNPs), magnetite (Fe3O4) nanomaterials have many advantageous features such as luminescent properties with a controllable wavelength, unique surface plasmon resonance properties or high magnetization in the presence of an external magnetic field. Another class of inorganic nanoparticles are silica‐based nanomaterials that can be investigated in two major groups: solid lipid nanoparticles (SNPs) and mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) 1. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles are widely explored silica based nanomaterials due to large surface areas and specific pore volumes owing to ordered pore structures, which enable drug loading. Furthermore, drug release rates can be regulated by editing the size of mesopores 2, 3. MSNs, such as 2D hexagonal MCM‐41 (Mobile Crystalline Material) and 3D cubic SBA‐15 (Santa Barbara Amorphous) are silica‐based porous materials with hundreds of empty channels, so called mesopores with a narrow size distribution in the range of 2–50 nm. Mesopores are appropriate supports for drug delivery and biomedical applications due to their high chemical and thermal stability 4. Their drug adsorption and release rates mainly depend on the textural and structural properties of the host‐matrix 5 and can be regulated to maximize cellular uptake 6. The approximate drug loading dose of conventional MSNs is about 200–300 mg which accounts for 600 mg drug/g silica 7.

First drug loaded into mesopores was isoprofen packed in MCM‐41 exhibiting a sustained drug release performance with improved loading ratio 8. Thereafter, biomedical studies on MSNs have grown rapidly and their development as a drug carrier has engendered in three generations 9, 10. The first generation was introduced for the sustained release with many challenges such as large particle sizes, irregular morphologies, several aggregations, cell level evaluations and in vivo applications. In conjunction with the fast development of synthetic chemistry, the second generation MSNs were constituted nano‐sized and uniform spherical morphology, tunable pore/particle sizes and compositions. Generation II MSNs have been constructed with various structures and morphologies such as hollow nanostructures, janus MSNs, yolk shell nanorattles (a special kind of core‐shell nanostructure) and organic–inorganic hybrid mesoporous silica. In addition, MSNs integrated with comprehensive functionalities have been presented as generation III, which were designed and fabricated in a more complex manner in regards to surface chemistry and synthesis approaches. The surface modifications are based on the silanol groups (Si‐OH) on the outer or inner mesoporous surfaces with various types of functional groups. The functional groups can be biological recognition ligands, peptides, aptamers, antibodies, nanovalves to control release profiles (e.g., stimuli responsive release, on‐demand release), genes for synergistically overcoming multidrug resistance (MDR) of cancer cells, biocompatible functional polymers/materials for improving blood circulation time and fluorescent agents for bioimaging. Consequently, the latest generation MSNs explore a wide variety of synthetic strategies for functionalization of inorganic nanoparticles with organic molecules and macromolecules.

Although, inorganic nanoparticles are highly stable and multifunctional, their biodegradability and biocompatibility have been disputed. Furthermore, burst release of active ingredients from the matrix is one of the major disadvantages of MSN limiting their use in clinical applications where controlled release is required. On the other hand, organic carriers are known for their high biocompatibility and biodegradability, but low stability and single functionality. The advancements in material science and drug delivery systems catalysed the fabrication of organic‐inorganic hybrid nanoparticles which combine desirable properties of organic and inorganic materials to overcome the weaknesses of MSNs 11, 12, 13, 14. Hybridization of organic and inorganic components can lead to multi‐functionality and enhanced material properties 15. The hybrid nanoparticles have significant properties of both inorganic and organic moieties and in addition they can be modified through the combination of functional elements. Also surface modification with the targeting moieties provides specific targeted imaging and therapeutic properties 1. Hybridized mesoporous nanoparticles can be synthesized via hydrolysis and condensation of organic and inorganic precursors under acidic or basic conditions resulting in monodisperse nanoparticles and tailored for internalization of various drugs 16, 17. These particles may have various morphologies such as stellate 18, ellipsoidal, spherical 19, octopus 20 and walnut kernel‐like 21. It would have been interesting to investigate the effects of these morphologies on drug loading efficiency, release kinetics, cellular uptake, subcellular localization, and cytotoxicity. Hybrid mesoporous materials are reported to act as host matrices for a wide range of drugs via weak interactions 8. The internal surfaces of mesopores can be functionalized to improve drug and carrier interaction. For instance, trimethylsilyl groups were incorporated inside the pore surfaces to enhance loading of hydrophobic drug molecules on to MSNs 18, 22.

This review article focuses on the advancements in mesoporous silica based organic‐inorganic hybrid nanoparticles developed as drug carriers targeting cancer cells. Brief introduction to the state‐of‐the‐art in both passive and active targeting methods are presented. Particularly, therapeutic, diagnostic and theranostic applications are discussed critically with emphases on triggered and ligand conjugated organic‐inorganic hybrid mesoporous silica nanomaterials.

2. Drug targeting to cancer cells

2.1. Passive targeting

Passive targeting is a kind of drug delivery strategy facilitated by nanoparticle fabrication techniques. The change in size, shape, charge and stiffness of the materials to enhance tissue accumulation, adhesion, cellular uptake of nanoparticles and drugs are part of the strategy 23. The polymeric drug carrier particles have more advantages than administration of free drugs like increased circulation time in the body because free drugs can be detected by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) and eliminated. Some anticancer drugs like camptothecin and doxorubicin (DOX) are effective in chemotherapy but the applications in humans were limited due to the poor water solubility of the drug. Therefore, a suitable solution for hydrophobic drug molecules is of prime importance 24. For instance, silicone oxide‐deposited DOX‐loaded stearic acid‐grafted‐chitosan nanoparticles were compared with stearic acid‐g‐chitosan polymeric micelles. The results showed that the nanoparticles have a more rapid drug release rate in vitro than the micelles and they could easily penetrate into the cells due to higher specific surface area obtained by their mesoporous structure 25 which, not only serve as unique drug reservoirs but also have a part in multiphasic release systems. In another study, drug delivery system using DOX loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticle composite nanofibers was fabricated which can release anti‐tumor drugs in two phases (burst release in the early stage and sustained release at a later stage) to reduce local recurrence of breast‐conserving therapy 26. The drug entrapped within MSNs must first be released at a solution state, then from polymeric fibers to the surrounding medium.

Polymeric particles may also be prone to delay or prevent recognition properties due to RES 24. Many types of generation II MSNs were synthesized with various structures and surface morphologies that could be used for targeted drug carrier systems passively through surface modifications with functional polymers. For example, poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) can significantly enhance the circulation time due to its excellent protein repellent properties 27. The polyethyleneimine‐polyethylene glycol (PEI‐PEG) decoration on the surface of the nanoparticles was reported to decrease RES uptake and resulted in the retention of about 8% of the administered particle dose at tumor site 28. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) is another type of polymer for functionalization of nanocarriers. In one of the studies, PVP was used as a protecting polymer adsorbed on the surface of silica microspheres and NaOH was employed as an etching agent. Mesopores were created in the silica microspheres owing to the protective nature of PVP and inhomogeneous etching 29. The surface modifications of recent organic‐inorganic silica hybrids with polymers are mostly based on PEG 27, PEI 28 , PVP 29, chitosan 25 and poly‐L‐lactic acid (PLLA) 26 for drug targeting to cancer cell (Table 1).

Table 1.

Passively targeted drug delivery or fluorescent imaging with organic‐inorganic hybrid silica nanosystems

| Treated cells/ animals | Drug molecules or imaging agent | Structure/hybrid type | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hep‐G2 mice | Docetaxel | PEGylated mesoporous silica nanorattle | 27 |

| MCF‐7/MDR mice | DOX and siRNA | Mesoporous silica nanoparticles were functionalized by PEI‐PEG copolymer | 28 |

| A549 | DOX | Stearic acid‐grafted chitosan (CS‐SA) core and SiO2 shell | 25 |

| HeLa | DOX and fluorescein | Fluorescent and cross‐linked organic−inorganic hybrid mesoporous poly‐(cyclotriphosphazene‐co‐fluorescein ) ‘PCTPF’ nanoshells | 36 |

| HeLa | Ibuprofen | Fluorescent poly(p‐phenylenevinylene) (PPV) | 34 |

| MDA‐MB‐231 mice | DOX | PLLA‐(MSN/DOX)‐DOX composite electrospun nanofibers | 26 |

| A549 | Rhodamine B | Combined a fluorescent inorganic silica core with a biocompatible polymer shell | 24 |

| HeLa | DOX | Luminescent YVO4:Eu3+ nanocrystals integrated mesoporous silica nanoparticles | 29 |

Meng and co‐worker 28 prepared MSNs functionalized with PEI‐PEG copolymer carrier to overcome DOX resistance in the MDR human breast cancer xenograft by co‐delivering DOX and siRNA that targets the P‐glycoproteins (P‐gp) drug exporter. MDR is one of the main obstacles in effective chemotherapeutic treatment of cancer, where pump and non‐pump drug resistances are reported as two major mechanisms. P‐gp and MRP‐1 (MDR‐associated protein‐1) are pump‐related gene products existing at the cellular and the nuclear membranes and pumps anticancer drugs to the extracellular matrix while drug‐induced expression of Bcl‐2 protein is responsible for the activation of anti‐apoptotic cellular defence as major mechanism in nonpump resistance 30, 31. Many studies have shown that co‐delivery of Bcl‐2 siRNA with chemotherapeutic drugs by functionalised MSNs downregulates the Bcl‐2 protein expression, which in turn could induce remarkable cell apoptosis 32, 33.

Co‐delivery of DOX and siRNA by the PEI‐PEG copolymer functionalised MSN nanocarriers resulted in synergistic inhibition of tumor growth in a MDR tumor xenograft model in vivo compared with free DOX and the carrier loaded with either drug or siRNA alone 28. Another approach for functionalization of mesoporous silica nanoparticles is the formation of core‐shell structure. An example for this approach is poly(p‐phenylenevinylene) (PPV) functionalized MSNs which were further coated with a layer of mesoporous silica shell to form the core‐shell structure. The PPV serve as a fluorescent polymer and the developed fluorescence MSNs with or without core‐shell structures were reported to improve the capabilities of drug loading, sustained drug release and cancer cell bioimaging 34.

2.2. Active targeting

During the last decade, surface‐functionalized, end‐capped MSNs have been designed for controlled anticancer drug delivery due to their low toxicity, high surface area and large accessible pore volumes which are suitable for loading drug molecules 35, 36. These systems have the capability of releasing the cargo only at the desired location by responding to certain external stimuli or specific ligand matching which was referred as active targeting 23, 37. Among stimuli response properties, pH changes represent an effective strategy especially for cancer therapy since the extracellular pH in tumour tissue is slightly lower than in normal tissue 35. Consequently, active targeting can not only be achieved by stimuli responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles that can respond to changes in pH 38, 39, 40, 41, temperature 42, 43, magnetism 44, 45, chemicals 46, enzymes 47, redox 48 or light 38, 49, 50, 51, 52, but also associated with receptor recognition reactions. We discussed these active targeting strategies based on the organic‐inorganic hybrid mesoporous silica nanocarriers for the therapeutic and diagnostic approaches in the next sections.

2.2.1. Therapeutic or diagnostic approach

2.2.1.1. Stimuli responsive organic‐inorganic hybrid silica nanomaterials

Stimuli responsive organic‐inorganic hybrid silica nanocarriers doped with chemotherapeutic drugs or imaging agents for therapeutic or bioimaging purposes are provided in Table 2. The pH sensing functions are of prime importance in MSN‐based triggered‐release nanocarriers. In one of the studies, fluorescent organic/inorganic hybrid MSNs were prepared with controllable redox‐responsive release of rhodamine B as a model drug 53. Indeed, many of hybrid materials prepared for controlled drug release on tumor location were often based on pH or glutathione (GSH) level changes because of acidic pH (5.0) and high GSH concentration levels (2−10 mM) on tumour intracellular environment compared with normal tissues 54. In another study, DOX hydrochloride was released by responding to acidic tumour intracellular environment 55. A dynamic cross‐linked supramolecular network of poly(glycidyl methacrylate)s (PGMAs) derivative chains was constructed on mesoporous silica nanoparticles via disulfide bond and ion‐dipole interactions between cucurbiturils and protonated diamines in the polymer chains, where this network was employed as a pH and GSH dual stimuli‐responsive nanovalve. Disulfide bonds between PGMA chains and MSNs endowed the hybrid material GSH responsiveness.

Table 2.

Stimuli responsive or ligand conjugated organic‐inorganic hybrid silicas for therapeutic or diagnostic purposes

| Target cell/animal | Therapy or imaging agent | Nanoparticle/bioconjugate type and triggering factors | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimuli responsive organic‐inorganic hybrid silicas | ||||

| A549 | DOX | – | Organic‐inorganic hybrid mesoporous nanoparticles with pH‐ and GSH‐ responsiveness | 55 |

| – | Rhodamine B | Fluorescent pH‐sensing organic/inorganic hybrid mesoporous silica nanoparticles | 53 | |

| – | Rhodamine 6G | Mesoporous SiO2 films, functionalized with high quantities of azochromophores as photodriven nanoimpellers | 52 | |

| KB‐V1 | DOX and siRNA | – | PEI coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles | 30 |

| Ligand conjugated organic‐inorganic hybrid silica nanomaterials | ||||

| U87 MG HEK 293 | DOX | GNPs@RGD peptide‐capped MSNs | 59 | |

| HCT116 mice | 5‐Fluorouracil | ‐ | MSN‐P(OEGMAa‐co‐ RGD peptide | 89 |

| HeLa HEK 293 | DiIb and DiOc as model drugs | ‐ | Folic acid‐conjugated and PEI‐functionalized MSNs | 90 |

| HeLa MCF‐7 | Camptothecin | Tumor homing and penetrating peptide (tLyP‐1) functionalized MSNs | 91 | |

poly(oligo(ethylene glycol)monomethyl ether methacrylate).

1,1’‐dioctadecyl‐3,3,3’,3’‐tetramethindocarbocyanine perchlorate.

3,3‐dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate.

Another approach to deliver drugs to specific locations is to control the drug release by light due to its non‐invasive nature. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles have large hollow interiors that serve as large reservoirs for enhanced drug‐loading capacity and demonstrate special structure–property relationships for nanomedicine 56. The first organic–inorganic hybrid hollow mesoporous organosilica‐based nanovehicles (HMOVs) were synthesised as nanocarriers. HMOVs with phenylene‐bridged silsesquioxane frameworks have been employed as excellent nano co‐delivery platforms for efficient intracellular transport of gene‐silencing agent namely the P‐gp and anticancer drugs. The co‐delivery of P‐gp associated short hairpin RNA and DOX enhanced chemotherapeutic efficiency due to higher intracellular DOX concentration 57. Not only the hollow structure of HMOVs was found to be responsible for the high cargo‐loading capacity, but also its phenylene‐bridged framework acted as pH‐responsive drug release.

2.2.1.2. Ligand conjugated organic‐inorganic hybrid silica nanomaterials

Despite the notable success of external and internal stimuli responsive organic‐inorganic hybrid silica nanoparticles, more specific applications were required in cancer therapy such as ligand conjugating strategy as active targeting in order to improve the specificity of nanoparticles towards tumor cells. For instance, traditional MSN drug release systems were not able to distinguish inflammatory tissues, resulting in damage of both inflammatory and healthy tissues 58. Thus, researchers searched for alternatives to improve the delivery efficiency and cancer specific recognition and focused on active targeting ligands, peptides and antibodies that recognize particular receptors in target cells with subsequent uptake through receptor‐mediated endocytosis. An example is functionalized MSNs showing sensitivity to pH by α‐amide‐β‐carboxyl unsaturated bond and further end‐capped with functional RGD peptide‐coated gold nanoparticles (GNPs). Hereby, bioactive surface of the GNPs‐peptide‐capped MSNs facilitated the binding to α v β 3 integrin overexpressed U87 MG cancer cells. On the contrary, limited internalization was observed in α v β 3 integrin negative HEK 293 cells 59. As majority of the publications related to ligand conjugated organic‐inorganic hybrid silica nanomaterials are designed for both therapeutic and imaging purposes, these will be discussed in the following section.

2.2.2. Theranostic approach

Theranostics describes the co‐delivery of therapeutic and imaging agents in a single formulation 60 where drug delivery can all be integrated into one functionalized nanoparticle 61. There have been many platforms that combine imaging and therapy for optimization of efficacy and safety of therapeutics such as nanocarriers related to light, magnetism, and sound 62.

Ligand‐conjugated organic‐inorganic hybrid silica nanoparticles with triggered mechanisms and stimuli responsive counterparts for theranostic purposes are summarised in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Various ligands that can specifically bind to receptors overexpressed in cancer cells were utilized for the design of targeted drug delivery systems 63. The differential expressions of receptor proteins, residing in cytosol, organelles or membrane are used as molecular markers. An example is the human epidermal growth factor receptor HER2 which is overexpressed in ∼30 % of breast cancers and used as a marker to target breast cancer cells 64. Overexpressed or specifically expressed receptors in various cancer tissues and cells are reported in literature 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70. As receptor‐ligand interactions are highly specific, this mechanism is applied for active targeting of nanocarriers or nanoconjugates 71.

Table 3.

Organic‐inorganic hybrid silicas with target‐ligand interactions for theranostic purposes

| Target cell/ animal | Chemo‐therapy agents | Imaging agents | Triggering event | Other therapy responsible agents | Targeting ligand | Target receptor | Nanoparticle/Bioconjugate type | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human squamous carcinoma cell spheroids (MCS) | DOX | – | NIR and enzyme dual responsive | Gold nanobipyramids (AuNBs) as a photothermal converter | Azobenzene and α‐cyclodextrin functionalized hyaluronic acid (HA) | CD44 is a major receptor for HA overexpressed in many solid tumor cells | HA(shell)‐MSNs‐AuNBs(core) triple‐layer core‐shell nanocomposites switchable system | 85 |

| AsPC‐1 mice | – | Iron oxide as MR contrast agent | NIR light | ICG fluorescent dye as a PTT agent, The gold nanoshells enhance the fluorescence of ICG | antibody (AntiNGAL) | Neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin (NGAL) | Encapsulated with iron oxide and ICG and then AntiNGAL‐conjugated theranostic triple‐layer‐gold nanoshells (TGNS) | 81 |

| U251/Normal human astrocytes, 1800 | DOX | – | pH sensitive and NIR stimulative | Graphene nanosheet as a PTT agent | IP peptide | Receptor chain 2 of interleukin 13 (IL‐13Rα2) | A targeting peptide (IP)‐modified mesoporous silica‐coated graphene nanosheet (GSPI) | 76 |

| A549 mice | DOX | – | NIR light | GNRs as a PTT agents | RGD peptide | αvβ3 integrin receptor | Conjugated RGD peptides on the terminal groups of PEG on mesoporous silica‐encapsulated GNRs | 86 |

| PC‐3 HDFs | – | – | NIR light | Gold shell as a PTT agent | EphrinA1 ligand | EphA2 receptor | Gold‐coated silica nanoshells conjugated to ephrinA1 ligand via PEG linker | 82 |

| SK‐BR‐3 HDF | – | – | NIR light | Gold shell as a PTT agent | Human epidermal growth factor (HER) | HER2 receptor | Gold‐coated silica nanoshells conjugated to HER via PEG linker | 64 |

| HeLa MCF‐7 | Campto‐thecin | Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) | NIR light | Au nanorod core as a PTT agent | tLyP1 tumor‐homing peptide | neuropilin‐1 (NRP1) receptor | tLyP1−Conjugated Mesoporous silica‐coated Au nanorod, (AuNR@SiO2) nanoshell | 84 |

| SK‐BR‐3 MCF‐10A | DOX | – | pH and NIR responsive | Mesoporous carbon cores serve as a drug carrier and PTT agent | SP13 ligand | HER2 receptor | SP13 peptide‐conjugated graphitic carbon (core) @ mesoporous silica nanospheres/(MMPSD) | 77 |

| SK‐BR‐3 MCF‐10A mice | DOX | FITC | pH and NIR responsive | semi‐graphitized carbon (sGC) on the inner wall can effectively convert NIR light into heat | DNA aptamer (HB5) | HER2 receptor | PEGylated mesoporous silica‐ carbon nanoparticles (MSCN) with HB5 aptamer | 63 |

| NCL positive MCF‐7 cancer cells | DOX | Cy5.5 fluorescence | NIR light | Graphene oxide (GO) gatekeeper converted NIR light into heat | Cy5.5 labelled AS1411 aptamer | Nucleolin receptor | Cy5.5‐AS1411 aptamer conjugate graphene oxide nanosheet coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN@GO) | 73 |

| MCF‐7 HEK‐293 | DOX Curcumin | – | NIR light | Cu1.8S | Aptamer‐modified GC‐rich DNA helix as gatekeepers and targeting ligand | Nucleolin receptor | DNA‐hybrid‐gated nanocarrier based on mesoporous silica‐coated Cu1.8S nanoparticles | 92 |

Table 4.

Stimuli responsive organic‐inorganic hybrid multifunctional silicas for theranostic purposes

| Target cell/animal | Chemo‐therapy agents | Imaging agents | Triggering event | Other stimuli‐responsive agents | Nanoparticle/Bioconjugate type | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SKOV3 | Indomethacin | Gd3+ ions as a T 1‐MR contrast agent | Temperature changes | p(NIPAm‐co‐AAm) was responsive to pH/temperature changes | Luminescent rattle‐type hollow mesoporous silica microspheres with a thermosensitive hydrogel via p(NIPAm‐co‐AAm conjugation | 93 |

| HeLa | DOX | Blue‐emitting AIE luminogen | pH responsive | ‐ | AIE luminogen‐functionalized hollow mesoporous silica nanospheres (FHMSNs) with pH‐ responsiveness | 94 |

| A549 mouse | DOX | Y2O3:Yb,Er core | pH/temperature and NIR light | Au25(SR)18 clusters were photodynamic (PDT) and photothermal therapy (PTT) agents. | Core/shell structured Y2O3:Yb,Er(core)@Y2O3:Yb(shell)@mSiO2‐Au25‐P(NIPAm‐MAA) (YSAP) up‐conversion nanoparticles | 95 |

| MCF‐7 | DOX | Gadolinium(III)‐chelated complexes as MRI contrast agents | NIR laser irradiation | ICG as photothermal agent | Gadolinium(III)‐chelated silica nanospheres loaded with DOX and ICG and then coated PDC (poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDC) | 96 |

| HeLa | DOX | Cu2‐x‐Se | pH and NIR light | Copper selenide (Cu2‐x‐Se) as a PTT agent | Cu2‐x‐Se nanoparticles core combined with DOX‐loaded MSN shell and then PEGylated | 80 |

| HeLa | DOX | CuS | pH and NIR light | CuS nanocrystal cores as PTT agents | CuS crystals @mSiO2‐PEG core–shell nanoparticles | 79 |

| HepG2 Chang liver cells | DOX | CuS | NIR laser irradiation | CuS as an efficient PTT agents | PEG‐modified DOX‐loaded/MSN@CuS nanohybrids | 78 |

| MCF‐7 mice | DOX | GNRs | pH and NIR light | GNRs as an PTT agents | DOX loaded mesoporous silica‐coated gold nanorods (GNRs@mSiO2‐DOX) | 74 |

| HeLa | DOX | GNRs | pH/temperature and NIR light | GNRs as an PTT agents and poly(N‐isopropylacrylamide)‐based N‐butyl imidazolium responsible for thermosensitivity | DOX loaded mesoporous silica shell‐coated GNRs | 97 |

As for stimuli responsive systems, especially Near‐Infrared (NIR) triggered multifunctional organic‐inorganic hybrid silica nanoparticles are commonly used as cancer theranostics. NIR‐triggered organic‐inorganic hybrid silica drug carriers include mainly two components; NIR absorption agents and a drug‐containing silica (mostly mesoporous) moiety, which can enable a synergistic treatment for cancer cells via dual effects of photothermal ablation and chemotherapy 72. Photothermal therapy (PTT) employs near‐infrared (NIR) laser photo‐absorbers to generate heat upon NIR laser irradiation. Indocyanine green (ICG) is one of the fluorescent dyes used for PTT, which absorbs NIR and converts light to heat in order to form localized hyperthermia in the cancerous tissue. Although ultraviolet (UV) and visible (Vis) lights have been used as exogenous stimuli to trigger drug release, concerns about high toxicity to healthy tissues and low penetration depth (∼10 mm) due to strong scattering ability of skin and soft tissues have limited their applications. NIR light triggered drug delivery systems offered some advantages such as deeper penetration, lower scattering and minimal damage 73. Gold nanorods (GNRs) as cores of nanoshells 74, gold layers in core‐shell nanoplatforms, gold nanocages 75, graphene nanosheets 76, graphitic 77 / semi‐graphitic carbon cores 63 and CuS nanoparticles 78, 79 and some other copper compounds 80 are the mostly studied NIR‐absorbing agents in NIR‐triggered hybrid silica nanocarriers.

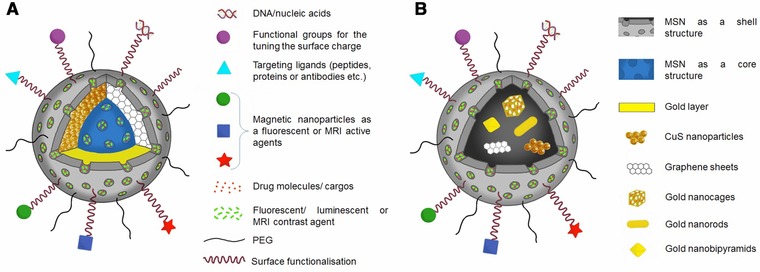

In an attempt to discuss NIR‐triggered silica nanocarriers in more details, core‐shell structure is regarded as a common denominator and these nanoconjugates are reviewed in two groups. One of the groups is represented with a mesoporous silica core and NIR‐responsive shell (Fig. 1A) is generally required as an additional outer mesoporous silica shell 81 encapsulated with drug, fluorescent agent or photothermal therapy agent. It is worth to mention that surface PEGylation might be required for higher stability and ligand conjugation 64, 82. An example to the first group of nanoconjugates is gold nanoshells (AuNS) with a dielectric core such as silica and a metallic gold layer which shows ~1 million‐fold greater absorption than conventional NIR dye, ICG 83.

Figure 1.

Two types of NIR‐triggered core‐shell type nanoshells; mesoporous silica core encapsulated with drug, fluorescent agent or photothermal therapy agent covered with an NIR responsive shell and an additional outer mesoporous silica shell functionalized for targeted delivery (A), NIR responsive core such as copper, graphene nanosheets and gold derivatives coated with mesoporous silica shell as a drug reservoir and functionalized surface (B).

The other group has a metal core and mesoporous silica shell structure (Fig. 1B) demonstrating many advantages in comparison to carbon derivative or single metal particles 76, 84, 85, 86. As an example for single metal particles, GNRs with nonporous structures exhibit low loading capacities and limited elasticity, restricting their applications in drug delivery 86. But they are still in use due to single‐ and two‐photon induced luminescence and longitudinal plasmonic resonance that can be tuned to near infrared wavelengths 87. Hence, the drug‐loaded mesoporous silica coating on the surface of this type of NIR‐converting agents improved biocompatibility, drug loading and post modification 77. A mesoporous silica‐coated graphene nanosheet (GS) was conjugated with a peptide for glioma targeting. The results showed that peptide conjugation enhanced cellular uptake in human glioma cell line, whereas normal astrocyte cells were not affected, indicating a selective therapeutic effect 76.

Another study focused on mesoporous silica coated graphitic carbon nanospheres conjugated with HER2 receptor specific SP13 peptide for DOX delivery with photothermal effect of NIR responsive graphitic carbon core on the SK‐BR‐3 breast carcinoma cells. The combined effect of nanocarrier system with NIR was remarkable with significantly lower IC50 of DOX (10.05 μg/mL) compared to that of free DOX (124.5 μg/mL) 77. A similar combined chemo‐photothermal therapy was attempted by the design of mesoporous silica encapsulated gold nanorods. A549 human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells were incubated with the nanocarrier loaded with DOX and a synergistic effect was reported with lower systematic toxicity 86. The multifunctional hybrid nanocarriers can enhance cancer therapy by providing chemo‐ and photothermal therapies while allowing fluorescence imaging for diagnostic purposes.

3. Concluding remarks

In the mid to late 1970s, the concept of polymer‐drug conjugates or “nano‐therapeutics” have initiated targeted or site‐controlled drug delivery systems in nanoscopic era. The discovery of three key technologies, PEGylation, active targeting to specific cells by ligands or other molecules conjugated to the drug delivery system and passive targeting to solid tumors via the EPR effect stimulated the development of polymeric and nano‐sized carriers as practical clinical applications from late 1980s to the present 88. Although MSNs perform well in preclinical tests, few clinical trials are performed and there are some comprehensible and essential hurdles regarding scale up of its synthesis to required dosage for acceptable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles 2. Herein, just a few of many topics were scrutinized related to silica based mesoporous organic‐inorganic hybrid nanocarrier systems in order to present latest developments in passive and active targeted drug delivery for cancer therapy. As our knowledge of material and biological sciences advances, so our ability to design more complex and multifunctional nano‐structures will continue to grow and MSNs have a promising future for innovative cancer treatments.

Practical application

This review highlights the most recent advances in the use of silica based organic‐inorganic hybrid drug carriers based on cancer therapy with different therapeutic, diagnostic and theranostic applications. Also their novel advantages through drug loading abilities, shape/size modifications and sophisticated functionalization processes were critically discussed in the light of technological developments. Multifunctionalisation techniques such as coating, grafting or capping allow specific responsiveness and homing properties to these nanocarriers. Not only passive or active targeting offer key technologies to tumor homing and penetrating but also photothermal therapy serves as an interesting tool for selective targeting of cancerous tissues.

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by the Research Fund of Ege University (16MUH052).

4 References

- 1. Vivero‐Escoto, J. L. , Huang, Y. T. , Inorganic‐organic hybrid nanomaterials for therapeutic and diagnostic imaging applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 3888–3927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Watermann, A. , Brieger, J. , Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as drug delivery vehicles in cancer. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yesil‐Celiktas, O. , Senyay, D. , The breadth and intensity of supercritical particle formation research with a projection on publication and patent disclosures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 7017‐7026. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pal, N. , Bhaumik, A. , Soft templating strategies for the synthesis of mesoporous materials: inorganic, organic‐inorganic hybrid and purely organic solids. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 189–190, 21–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang, M. , Liu, J. , Kuang, Y , Li, Q. et al., Ingenious pH‐sensitive dextran/mesoporous silica nanoparticles based drug delivery systems for controlled intracellular drug release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 98, 691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lu, J. , Liong, M. , Zink, J. I. , Tamanoi, F. , Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a delivery system for hydrophobic anticancer drugs. Small 2007, 3, 1341–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bharti, C. , Naqaich, U. , Pal, A. K. , Gulati, N. , Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in target drug delivery system: a review. Int J Pharma Investig. 2015, 5, 124–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vallet‐Regí, M. , Colilla, M. , González, B. , Medical applications of organic–inorganic hybrid materials within the field of silica‐based bioceramics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 596–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen, Y. , Zhang, H. , Cai, X. , Ji, J. et al., Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanocarriers for stimuli‐responsive target delivery of anticancer drugs. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 92073–92091. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen, Y. , Chen, H. , Shi, J. , Drug delivery/imaging multifunctionality of mesoporous silica‐based composite nanostructures. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 917–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cabral, H. , Matsumoto, Y. , Mizuno, K. , Chen, Q. et al., Accumulation of sub‐100 nm polymeric micelles in poorly permeable tumours depends on size. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 815–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He, Q. , Shi, J. , Zhu, M. , Chen, Y. et al., The three‐stage in vitro degradation behavior of mesoporous silica in simulated body fluid. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 131, 314–320. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Croissant, J. , Cattoën, X. , Wong Chi Man, M. , Dieudonné, P. et al., Protein‐gold clusters‐capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for high drug loading, autonomous gemcitabine/doxorubicin co‐delivery, and in‐vivo tumor imaging. J. Control. Release 2016, 229, 183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taylor‐Pashow, K.M. , Della Rocca, J. , Huxford, R. C. , Lin, W. , Hybrid nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Chem. Commun. 2010, 32, 5832–5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pandey, S. , Mishra, S. B. , Sol‐gel derived organic‐inorganic hybrid materials: synthesis, characterizations and applications. J. Sol‐Gel Sci. Technol. 2011, 59, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yesil‐Celiktas, O. , Pala, C. , Cetin‐Uyanikgil, E. O. , Sevimli‐Gur, C. , Synthesis of silica‐PAMAM dendrimer nanoparticles as promising carriers in neuroblastoma cells. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 519, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang, K. , Xu, L. , Jiang, J. , Calin, N. et al., Controllable fabrication of dendritic mesoporous silica–carbon nanospheres for anthracene removal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2427–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang, K. , Zhang, Y. , Hou, Q. , Yuan, E. et al, Novel synthesis and molecularly scaled surface hydrophobicity control of colloidal mesoporous silica. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2011, 143, 401–405. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luo, L. , Liang, Y. , Erichsen, E. S. , Anwander, R. , Monodisperse mesoporous silica nanoparticles of distinct topology. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 495, 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang, L. , Chen, Y. , Li, Z. , Li, L. et al, Tailored synthesis of octopus‐type janus nanoparticles for synergistic actively‐targeted and chemo‐photothermal therapy. Angew. Chemie ‐ Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2118–2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ge, K. , Ren, H. , Sun, W. , Zhao, Q. et al., Walnut kernel‐like mesoporous silica nanoparticles as effective drug carrier for cancer therapy in vitro. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2016, 18, 81. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang, K. , Albela, B. , He, M. Y. , Wang, Y. M. et al., Tetramethyl ammonium as masking agent for molecular stencil patterning in the confined space of the nano‐channels of 2D hexagonal‐templated porous silicas. PCCP 2009, 11, 2912–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhu, Y. , Liao, L. , Applications of nanoparticles for anticancer drug delivery: a review. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 4753–4773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Müllner, M. , Schallon, A. , Walther, A. , Freitag, R. et al., Clickable, biocompatible, and fluorescent hybrid nanoparticles for intracellular delivery and optical imaging. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yuan, H. , Bao, X. , Du, Y‐Z. , You, J. et al., Preparation and evaluation of SiO2‐deposited stearic acid‐g‐chitosan nanoparticles for doxorubicin delivery. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2012, 7, 5119–5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yuan, Z. , Pan, Y. , Cheng, R. , Sheng, L. et al., Doxorubicin‐loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticle composite nanofibers for long‐term adjustments of tumor apoptosis. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li, L. , Tang, F. , Liu, H. , Liu, T. et al., In vivo delivery of silica nanorattle encapsulated docetaxel for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy with low toxicity and high efficacy. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 6874–6882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meng, H. , Mai, W. X. , Zhang, H. , Xue, M. et al., Codelivery of an optimal drug/siRNA combination using mesoporous silica nanoparticles to overcome drug resistance in breast cancer in vitro and in vivo. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 994–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cheng, Z. , Ma, P. , Hou, Z. , Wang, W. et al., YVO 4: Eu 3+ functionalized porous silica submicrospheres as delivery carriers of doxorubicin. Dalt. Trans. 2012, 41, 1481–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meng, H. , Liong, M. , Xia, T. , Li, Z. et al., Engineered design of mesoporous silica nanoparticles to deliver doxorubicin and Pgp siRNA to overcome drug resistance in a cancer cell line. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Castillo, R. R. , Colilla, M. , Vallet‐Regi, M. , Advances in mesoporous silica‐based nanocarriers for co‐delivery and combination therapy against cancer. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2017, 14, 229‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhou, X. , Chen, L. , Nie, W. , Wang, W. et al., Dual‐responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles mediated codelivery of doxorubicin and Bcl‐2 SiRNA for targeted treatment of breast cancer. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 22375–22387. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taratula, O. , Garbuzenko, O. B. , Chen, A. M. , Minko, T. , Innovative strategy for treatment of lung cancer: targeted nanotechnology‐based inhalation co‐delivery of anticancer drugs and siRNA. J. Drug Target. 2011, 19, 900–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qu, Y. , Feng, L. , Tong, C. , Liu, B. et al., Poly(p‐phenylenevinylene) functionalized fluorescent mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug release and cell imaging. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 182, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen, Z. , Li, Z. , Lin, Y. , Yin, M. et al., Biomineralization inspired surface engineering of nanocarriers for pH‐responsive, targeted drug delivery. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 1364–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sun, L. , Liu, T. , Li, H. , Yang, L. et al., Fluorescent and cross‐linked organic‐inorganic hybrid nanoshells for monitoring drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 4990–4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Upponi, J. R. , Torchilin, V. P. , Passive vs. active targeting: an update of the epr role in drug delivery to tumors, in: Alonso M. J., Garcia‐Fuentes M. (Ed.), Nano‐Oncologicals New Targeting and Delivery Approaches, Springer Cham, Heidelberg, New York¸ Dordrecht London: 2014, pp. 3–46. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aznar, E. , Marcos, M. D. , Martinez‐Manez, R. , Sancenon, F. et al, pH‐ and photo‐switched release of guest molecules from mesoporous silica supports. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6833–6843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. He, Y. , Luo, L. , Liang, S. , Long, M. et al., Amino‐functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles as efficient carriers for anticancer drug delivery. J. Biomater. Appl. 2017, 32, 524‐532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu, R. , Zhang, Y. , Zhao, X. , Agarwal, A. et al., pH‐responsive nanogated ensemble based on gold‐capped mesoporous silica through an acid‐labile acetal linker. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang, C. , Li, Z. , Cao, D. , Zhao, Y.‐L. et al., Stimulated release of size‐selected cargos in succession from mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Angew. Chemie ‐ Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5460–5465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Angelos, S. , Choi, E. , Vögtle, F. , De Cola, L. et al., Photo‐driven expulsion of molecules from mesostructured silica nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 6589–6592. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aznar, E. , Mondragon, L. , Ros‐Lis, J. V. , Sancenon, F. et al., Finely tuned temperature‐controlled cargo release using paraffin‐capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Angew. Chemie ‐ Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 11172–11175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang, L. , Wang, T. , Li, L. , Wang, C. et al., Multifunctional fluorescent‐magnetic polyethyleneimine functionalized Fe3O4/mesoporous silica yolk/shell nanocapsules for siRNA delivery. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 8706–8708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Martínez‐Carmona, M. , Colilla, M. , Vallet‐Regí, M. , Smart mesoporous nanomaterials for antitumor therapy. Nanomaterials 2015, 5, 1906–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lai, C.‐Y. , Trewyn, B. G. , Jesftinija, D. M. , Jeftinija, K. et al., A mesoporous silica nanosphere‐based carrier system with chemically removable CdS nanoparticle caps for stimuli‐responsive controlled release of neurotransmitters and drug molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Agostini, A. , Mondragon, L. , Coll, C. , Aznar, E. et al., Dual enzyme‐triggered controlled release on capped nanometric silica mesoporous supports. ChemistryOpen 2012, 1, 17–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Patel, K. , Angelos, S. , Dictel, W. R. , Coskun, A. et al., Enzyme‐responsive snap‐top covered silica nanocontainers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2382–2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhu, Y. , Fujiwara, M. , Installing dynamic molecular photomechanics in mesopores: a multifunctional controlled‐release nanosystem. Angew. Chemie ‐ Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2241–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nguyen, T. D. , Leung, K. C.‐F. , Liong, M. , Liu, Y. et al., Versatile supramolecular nanovalves reconfigured for light activation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 2101–2110. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vivero‐Escoto, J. L. , Slowing, I. I. , Wu, C.‐W. , Lin, V. S‐Y. , Photoinduced intracellular controlled release drug delivery in human cells by gold‐capped mesoporous silica nanosphere. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3462–3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Iatsunskyi, I. , Pavlenko, M. , Viter, R. , Jancelewicz, M. et al., Tailoring the structural, optical, and photoluminescence properties of porous silicon/TiO2 nanostructures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 7164–7171. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wan, X. , Wang, D. , Liu, S. , Fluorescent pH‐Sensing organic/inorganic hybrid mesoporous silica nanoparticles with tunable redox‐responsive release capability. Langmuir 2010, 26, 15574–15579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bai, L. , Wang, X.‐H. , Song, F. , Wang, X.‐L. et al., ‘AND’ logic gate regulated pH and reduction dual‐responsive prodrug nanoparticles for efficient intracellular anticancer drug delivery. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li, Q.‐L. , Xu, S.‐H. , Zhou, H. , Wang, X. et al., PH and glutathione dual‐responsive dynamic cross‐linked supramolecular network on mesoporous silica nanoparticles for controlled anticancer drug release. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 28656–28664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li, Y. , Shi, J. , Hollow‐structured mesoporous materials: chemical synthesis, functionalization and applications. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 3176–3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wu, M. , Chen, Y. , Zhang, L. , Li, X. et al., A salt‐assisted acid etching strategy for hollow mesoporous silica/organosilica for pH‐responsive drug and gene co‐delivery. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 766–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Martinez‐Carmona, M. , Lozano, D. , Colilla, M. , Vallet‐Regi, M. , Lectin‐conjugated pH‐responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeted bone cancer treatment. Acta Biomaterialia 2018, 65, 393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chen, G. , Xie, Y. , Peltier, R. , Lei, H. et al., Peptide‐decorated gold nanoparticles as functional nano‐capping agent of mesoporous silica container for targeting drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 11204–11209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Charron, D. M. , Chen, J. , Zheng, G. , Theranostic lipid nanoparticles for cancer medicine, in: Mirkin C. A. et al. (Ed.), Nanotechnology‐Based Precision Tools for the Detection and Treatment of Cancer, Springer International Publishing; Switzerland: 2015, pp.103–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Feng, Y. , Panwar, N. , Tng, D. J. H. , Tjin, S. C. et al., The application of mesoporous silica nanoparticle family in cancer theranostics. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2016, 319, 86–109. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chen, X. , Wong, S. , Cancer theranostics: an introduction, in: Chen X., Wong S. (Ed.), Cancer Theranostics, Elsevier Inc, USA: 2014, pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang, K. , Yao, H. , Meng, Y. , Wang, Y. et al., Specific aptamer‐conjugated mesoporous silica‐carbon nanoparticles for HER2‐targeted chemo‐photothermal combined therapy. Acta Biomater. 2015, 16, 196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lowery, A. R. , Gobin, A. M. , Day, E. S. , Halas, N. J. et al., Immunonanoshells for targeted photothermal ablation of tumor cells. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2006, 1, 149–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mankoff, D. A. , Link, J. M. , Linden, H. M. , Sundararajan, L. et al., Tumor receptor imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 49, 149–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dorsam, R. T. , Gutkind, J. S. , G‐protein‐coupled receptors and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007, 7, 79–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gessi, S. , Merighi, S. , Sacchetto, V. , Simioni, C. , Borea, P. A. , Adenosine receptors and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta ‐ Biomembr. 2011, 1808, 1400–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Iqbal, N. , Iqbal, N. , Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in cancers: overexpression and therapeutic implications. Mol. Biol. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nahta, R. , Hortobagyi, G. N. , Esteva, F. J. , Growth factor receptors in breast cancer: potential for therapeutic intervention. Oncologist 2003, 8, 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Belfiore, A. , Malaguarnera, R. , Insulin receptor and cancer, Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2011, 18, 125–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Akhtar, M. J. , Ahamed, M. , Alhadlaq, H. A. , Alrokayan, S. A. et al., Targeted anticancer therapy: overexpressed receptors and nanotechnology. Clin. Chim. Acta 2014, 436, 78–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhang, L. , Li, Y. , Jin, Z. , Yu, J. C. et al., An NIR‐triggered and thermally responsive drug delivery platform through DNA/copper sulfide gates. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 12614–12624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tang, Y. , Hu, H. , Zhang, M. G. , Song, J. et al., An aptamer‐targeting photoresponsive drug delivery system using ‘off–on’ graphene oxide wrapped mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 6304–6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Monem, A. S. , Elbialy, N. , Mohamed, N. , Mesoporous silica coated gold nanorods loaded doxorubicin for combined chemo‐photothermal therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 470, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hu, F. , Zhang, Y. , Chen, G. , Li, C. et al., Double‐Walled Au Nanocage/SiO2 nanorattles: integrating SERS imaging, drug delivery and photothermal therapy. Small 2015, 11, 985–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wang, Y. , Wang, K. , Zhao, J. , Liu, X. et al., Multifunctional mesoporous silica‐coated graphene nanosheet used for chemo‐photothermal synergistic targeted therapy of glioma. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 4799−4804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wang, Y. , Wang, K. , Zhang, R. , Liu, X. et al., Synthesis of core‐shell graphitic carbon @ silica nanospheres with photothermochemotherapy. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 7870–7879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wu, L. , Wu, M. , Zeng, Y. , Zhang, D. et al., Multifunctional PEG modified DOX loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticle@CuS nanohybrids as photo‐thermal agent and thermal‐triggered drug release vehicle for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment. Nanotech. 2015, 26, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Liu, X. , Ren, Q. , Fu, F. , Zou, R. et al., CuS@mSiO2 ‐PEG core–shell nanoparticles as a NIR light responsive drug delivery nanoplatform for efficient chemo‐photothermal therapy. Dalt. Trans. 2015, 44, 10343–10351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Liu, X. , Wang, Q. , Li, C. , Zou, R. et al., Cu2‐xSe@mSiO2‐PEG core‐shell nanoparticles: a low‐toxic and efficient difunctional nanoplatform for chemo‐photothermal therapy under near infrared light radiation with a safe power density. Nanoscale. 2014, 6, 4361–4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Chen, W. , Ayala‐Orozco, C. , Biswal, N. C. , Perez‐Torres C. et al., Targeting of pancreatic cancer with magneto‐fluorescent theranostic gold nanoshells. Nanomed (Lond) 2014, 9, 1209–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Gobin, A. M. , Moon, J. J. , West, J. L. , EphrinA I‐targeted nanoshells for photothermal ablation of prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2008, 3, 351–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Melancon, M. P. , Lu, W. , Yang, Z. , Zhang, R. et al., In vitro and in vivo targeting of hollow gold nanoshells directed at epidermal growth factor receptor for photothermal ablation therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 1730–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Xu, B. , Ju, Y. , Cui, Y. , Song, G. et al., TLyP‐1‐conjugated Au‐nanorod@SiO2 core‐shell nanoparticles for tumor‐targeted drug delivery and photothermal therapy. Langmuir 2014, 30, 7789–7797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Chen, X. , Liu, Z. , Parker, S. G. , Zhang, X. et al., Light‐Induced hydrogel based on tumor‐targeting mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a theranostic platform for sustained cancer treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016, 8, 15857–15863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Shen, S. , Tang, H. , Zhang, X. , Ren, J. et al., Targeting mesoporous silica‐encapsulated gold nanorods for chemo‐photothermal therapy with near‐infrared radiation. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3150–3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Durr, N. J. , Larson, T. , Smith, D. K. , Korgel, B. A. et al., Two‐photon luminescence imaging of cancer cells using molecularly targeted gold nanorods. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 941–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hoffman, A. S. , The origins and evolution of ‘controlled’ drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2008, 132, 153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Pan, G. , Jia, T.‐t. , Huang, Q.‐x. , Qui, Y.‐y. et al., Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs)‐based organic/inorganic hybrid nanocarriers loading 5‐Fluorouracil for the treatment of colon cancer with improved anticancer efficacy. Colloids Surf., B 2017, 159, 375–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Rosenholm, J. M. , Peuhu, E. , Eriksson, J. E. , Sahlgren, C. et al., Targeted intracellular delivery of hydrophobic agents using mesoporous hybrid silica nanoparticles as carrier systems. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 3308–3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Xu, B. , Ju, Y. , Song, G. , Cui, Y. , tLyP‐1‐conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles for tumor targeting and penetrating hydrophobic drug delivery. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2013, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zhang, Y. , Hou, Z. , Ge, Y. , Deng, K. et al., DNA‐Hybrid‐Gated photothermal mesoporous silica nanoparticles for NIR‐Responsive and aptamer‐targeted drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 20696–20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kang, X. , Cheng, Z. , Yang, D. , Ma, P. et al., Design and synthesis of multifunctional drug carriers based on luminescent rattle‐type mesoporous silica microspheres with a thermosensitive hydrogel as a controlled switch. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 1470–1481. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Fan, Z. , Li, D. , Yu, X. , Zhang, Y. et al., AIE Luminogen‐functionalized hollow mesoporous silica nanospheres for drug delivery and cell imaging. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 3681–3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lv, R. , Yang, P. , He, F. , Gai, S. et al., An imaging‐guided platform for synergistic photodynamic/photothermal/chemo‐therapy with pH/temperature‐responsive drug release. Biomaterials 2015, 63, 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Cao, M. , Wang, P. , Kou, Y. , Wang, J. , Gadolinium(III)‐Chelated silica nanospheres integrating chemotherapy and photothermal therapy for cancer treatment and magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 25014–25023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Baek, S. , Singh, R. K. , Kim, T.‐H. , Seo, J.‐W. et al., Triple hit with drug carriers: pH‐ and temperature‐responsive theranostics for multimodal chemo‐ and photothermal therapy and diagnostic applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 8967–8979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]