Abstract

Morphological engineering techniques have recently become popular, since they are used to increase the production of a variety of metabolites and enzymes when fungi are grown in submerged cultures. This study aimed to facilitate cellulase production by adding aluminum oxide to Trichoderma viride My precultures.

The results showed that the highest cellulase activity was achieved when aluminum oxide at 10 g/L was used, and the activities of cellulase for filter paper and endoglucanase activity assays increased from 519.11 to 607.35 U/mL by 17.1%, and from 810.08 U/mL to 917.59 U/mL by 13.3%, compared with the control, respectively. Addition of aluminum oxide decreased the size of T. viride My pellets and increased the final pH. The changes in pellet diameter after the addition of different concentrations of aluminum oxide were fitted using a modified exponential decay model, which could precisely predict the pellet size by controlling aluminum oxide concentration.

The optimum concentration of microparticles, and therefore pellet size, could significantly improve cellulase production, which is an encouraging step towards commercial cellulase production.

Keywords: Aluminum oxide microparticles, Cellulase production, Exponential decay model, Morphological engineering, Trichoderma viride

Abbreviations

- EG

Endoglucanase

- FPA

Filter paper activity

1. Introduction

Cellulase is an important enzyme in the food, animal feed, textile, starch processing, pulp and paper, alcohol fermentation, pharmaceutical, and brewing industries 1, 2 and it is mainly produced by the filamentous fungi Trichoderma viride, due to its high cellulase productivity, safety and overproducing capacity in industry 3. Recent studies have shown that the use of bioethanol as fuel could lead to the rapid development of cellulose‐based industries 4. However, the high cost of cellulase is a major obstacle for commercializing bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass 5, and investigations on new approaches to improve cellulase yield are ongoing 6.

Filamentous fungi are morphologically complex, differing in form between surface and submerged growth, as well as various culture medium compositions and physical environments 7. Fungi grown in submerged cultures exhibit different morphological forms such as dispersed mycelia and densely interwoven mycelia called pellets. Mycelial morphology in submerged cultures has a strong impact on metabolite biosynthesis 8, 9. The pellet size and structure affects the mixing of the suspension (broth viscosity) and mass transfer (mainly of oxygen and nutrients) in submerged cultures 10. Dispersed mycelia are better supplied with oxygen and nutrients than large pellets, whose inner cores might contain inactive or dead biomass 11.

The maximal performance of fungi during fermentation could vary according to their morphology, which is difficult to control, especially during mass production 11. Nevertheless, a novel approach to the targeted control of fungal morphology was recently introduced, namely morphological engineering 12, involving the addition of microparticles to fermentation media to control the morphological development of filamentous microorganisms 9, 11, 13. Germec et al. 14 investigated different fermentation strategies in fed‐batch fermentation (suspended, immobilized cell, biofilm and microparticle‐enhanced bioreactor) for β‐mannanase production by using recombinant Aspergillus sojae. They found that the enzyme activity was significantly enhanced by addition of microparticles compared to other fed‐batch fermentation strategies. Further development of this approach could result in morphological engineering targeted toward improving enzyme production by filamentous fungi. However, none of the existing methods allow for precise morphological adjustments. Mathematical models are important to describe complicated processes of dynamic change, particularly when optimizing biological processes and predicting regular pattern changes. Quantified morphological information (pellet size) can be used to construct morphologically structured change models of predictive value. Quantified mathematical modeling to predict optimal pellet diameter could improve the design and operation of fungal fermentations with the most efficient morphology, and increase the application of laboratory findings for cellulase production on a commercial scale. Therefore, this study aimed to enhance cellulase production and evaluate fungal morphology after the addition of aluminum oxide to the preculture medium of Trichoderma viride My using the morphological engineering technique.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Microorganisms

T. viride My, a mutant strain generated by 12C6+ ion irradiation of the T. viride strain GSTCC 62010 (NM01), was provided by the Biophysics Laboratory of the Institute of Modern Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). The working culture was grown on potato dextrose agar slants at 30°C for 6 days, and stored at 4°C. T. viride My was transferred at monthly intervals to fresh sterile agar slants to maintain viability. Before fermentation, the slants were washed with sterile 0.1% (w/v) peptone water to obtain a spore suspension, which was used to inoculate the preculture at 106 cells/mL.

2.2. Shake‐flask fermentation

Fermentation was conducted in shake flasks with a working volume of 50 mL (the total volume of each flask was 250 mL) on a rotary shaker. The preculture medium consisted of 7.5 g of CMC‐Na, 5 g of peptone, 2 mL of Tween‐80, 0.3 g of MgSO4·7H2O, 2.0 g of K2HPO4, 0.3 g of CaCl2, 0.005 g of FeSO4·7H2O, 0.0016 g of MnSO4·H2O, 0.0014 g of ZnSO4·7H2, 0.002g of CoCl2 per liter of deionized water. The fermentation medium 15 consisted of 7.5 g of CMC‐Na, 2 mL of Tween‐80, 0.3 g of MgSO4·7H2O, 1.4 g of (NH4)2SO4, 2.0 g of K2HPO4, 0.3 g of CaCl2, 0.005 g of FeSO4·7H2O, 0.0016 g of MnSO4 ·H2O, 0.0014 g of ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.002 g of CoCl2 per liter of deionized water.

To affect fungal morphology, aluminum oxide (Al2O3, 11037, Sigma‐Aldrich, powder suspended in 100 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.5) 13, 16 were added to the preculture medium at 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 g/L, in individual preculture flasks. Preculture medium without aluminum oxide was used as a control. The fermentation medium was inoculated with 24 h precultures at 5% (v/v). All fermentation processes were conducted at 30°C and a constant rotary speed of 200 rpm for 5 days. Samples were recovered daily and analyzed for cellulase activity and pellet size. Additionally, another set of experiments was conducted for final pH measurement of the shake‐flask fermentations.

2.3. Determination of cellulase activity

Cellulase activity was measured using the filter paper activity (FPA) assay as reported previously 17, 18, with minor modifications. A 3 mm × 4 mm filter paper (Whatman No. 1) disk was soaked with citric acid buffer (0.05 M, pH 4.8, 1.5 mL) and digested with 0.5 mL of the enzyme solution at 50°C for 60 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 3 mL of dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS), followed by incubation in boiling water for 5 min. The samples were cooled in an ice bath. The reducing sugar content produced during the 60 min reaction was determined by measuring the absorbance at 540 nm. One unit of FPA activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that generated 1 μg of reducing sugar in 1 min.

Endoglucanase (EG) activity was determined using a previously reported method 19 with modifications. Carboxymethyl cellulose (2%, pH 4.8, 1.5 mL) was digested with 0.5 mL of enzyme solution at 50°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 3 mL of DNS, followed by incubation in boiling water for 5 min. The samples were cooled in an ice bath. The reducing sugar content produced in the 30 min reaction was determined by measuring the absorbance at 540 nm. One unit of EG activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that generated 1 μg of reducing sugar in 1 min. Measurements of all samples were performed in triplicate, and mean values were calculated. The absorbance values were converted to cellulase activity by using equations generated from standard curves, as shown in Eqs. (1) and (2).

| (1) |

where is the concentration of reducing sugars (mg/mL) released during the reaction.

| (2) |

where the cellulase activity refers to the FPA or EG assay value, Df is the dilution factor, and t is the duration of the reaction in minutes.

2.4. Analysis of pellet size in the shake‐flask fermentation

The mean pellet diameter and fungal morphology were analyzed using a light microscope (Olympus BX53, Japan) equipped with an imaging system (Olympus DP72, Japan). Unfiltered broth (40 mL) was poured into an 18 cm Petri dish, and digital photographs were captured. The images were first contrasted to appear black 16, and the diameters of 60 randomly selected pellets were measured using the image analysis software, Image J (1.42q/Java 1.6.0_10 [32‐bit]). The diameters were measured as follows 20: a digital photograph was opened with Image J→a pellet was selected using the Elliptical tool→ the height and width was recorded→the diameter was calculated according to the height and width of pellet.

2.5. Kinetic parameters

After the cellulase activity and pellet size of each sample were measured, the residual sugar concentration in the fermentation broth was determined using 3,5‐dinitrosalycylic acid method according to Miller et al. 21. The kinetic parameters of the enzyme yield (Yp, U/mL), maximum enzyme production rate (QP, U/(mL h)), and sugar consumption rate (QS, g/(L h)) were calculated. The enzyme yield (Yp, U/mL) was calculated as the actual enzyme activity and expressed as U per mL broth (U/mL). The maximum enzyme production rate (QP, U/(mL h)) and sugar consumption rate (QS, g/(L h)) were determined from the maximum slopes in the plots of enzyme produced and substrate utilized versus fermentation time 22, 23.

2.6. Mathematical model

Pellet diameters after the addition of different concentrations of aluminum oxide to the preculture during shake‐flask fermentation were fitted using modified exponential decay equations 24, 25, and were used to predict the change in pellet diameter with the addition of aluminum oxide at various concentrations. The modified exponential decay model is given as follows:

| (3) |

where Y is the diameter of the pellet, y0 is a specific value when c is approximately 30 g/L aluminum oxide, A1 is the constant value for each fit, kc is the constant rate (L/g), and c is the concentration of aluminum oxide added to the preculture (g/L). The following assumptions served as the basis for mathematical modeling: a.The aluminum oxide microparticles of a size are completely homogeneous; b. Microbial cultures are practically saturated by substrate level.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All fermentation processes and measurements were performed in triplicate, and reported values represent the mean. The error bars indicate the standard deviation (SD) of the mean of triplicate experiments. The data were analyzed using one‐way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's test (SPSS, Version 20.0).

3. Results and discussion

In this work, aluminum oxide microparticles, targeted control agent, were used for cellulase production by T. viride My, and the cellulase activity, fungal morphology, mathematical model were investigated.

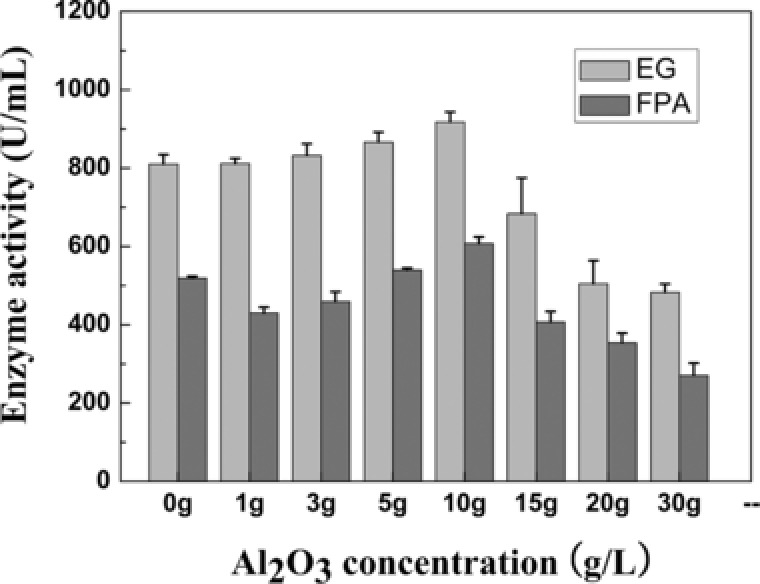

3.1. Effect of aluminum oxide on cellulase activity during shake‐flask fermentation

Shake‐flask fermentations clearly showed that cellulase activity varied with the change in aluminum oxide concentration (Fig. 1), and was efficiently improved. The highest cellulase activity was achieved with 10 g/L aluminum oxide. Under these conditions, the resulting cellulase activities in the FPA (607.35 U/mL) and EG (917.59 U/mL) assays were increased by 17.1% and 13.3%, respectively, compared to that of the control (Table 1). The EG activity improved with increased aluminum oxide concentration up to 10 g/L. When the concentration of the microparticles was higher than 10 g/L, a decrease was observed. Similarly, the addition of aluminum oxide at concentrations higher than 10 g/L decreased FPA activity to near the level observed in the control fermentation (Fig. 1). This suggested that higher concentrations of microparticles can provide smaller pellet size, and thus increase the viscosity of the fermentation broth. This increase in viscosity negatively affects the mass transfer of oxygen and nutrients, microbial growth, and consequently, product formation during fermentation 10. Therefore, although small pellets are better supplied with oxygen and nutrients than large pellets, whose inner cores may contain inactive or dead biomass, the growth of very small fungal pellets negatively affects the products formation during fermentation 10, 11. Coban et al. 26 studied Aspergillus ficuum fermentation in the presence of aluminum oxide and talcum. They reported that the addition of 15 g/L aluminum oxide and 15 g/L talcum increased phytase activity to 2.01 U/mL and 2.93 U/mL, respectively, compared with that in the control (1.02 U/mL), and microparticle concentrations higher than 15 g/L decreased phytase activity. A similar result was reported by Kaup et al. 13, who observed that the addition of 0.5‐10 g/L talcum to Caldariomyces fumago fermentation enhanced the production of chloroperoxidase; however, higher concentrations decreased enzyme activity. In this study, the increase in cellulase activity was correlated with a considerable change in pellet diameter, caused by the addition of aluminum oxide microparticles to the preculture (Figs. 1 and 2). Moreover, Karahalil et al. 27 investigated polygalacturonases (PGs) production of Aspergillus sojae by using shake flask fermentation by adding aluminum oxide as microparticles to the media. They found that the the highest PG activity of 34.55±0.5 U/mL was achieved with the addition of 20 g/L of Al2O3. The maximum PG activity was 2.2‐fold higher than control (15.64±3.3 U/mL).

Figure 1.

Effects of aluminum oxide microparticles on the cellulase activity of Trichoderma viride My production medium after 120 h of fermentation. Data are reported as mean values, and the error bars represent the SD of triplicate experiments. EG, endoglucanase; FPA, filter paper activity.

Table 1.

Effect of various concentrations of aluminum oxide on the maximum cellulase production, enzyme production rate, sugar consumption rate, final pH, and fungal morphology of T. viride My in shake‐flask fermentation

| Aluminum oxide conc. (g/L) | Max. cellulase enzyme activity (Yp. U/mL) | Max. enzyme production rate (QP, U/(mL h)) | Max. sugar consumption rate (Qs, g/(L h)) | pH after 120 h of shake‐flask fermentation | Fungal morphology | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPAa | EGb | FPA | EG | ||||

| 0 | 519.11 ± 4.86 | 810.08 ± 24.47 | 5.69 | 11.89 | 0.12 | 3.19 | Large pellets |

| 1 | 430.03 ± 14.59 | 811.49 ± 13.44 | 6.30 | 11.67 | 0.09 | 3.25 | Large pellets |

| 3 | 459.1 ± 24.95 | 832.42 ± 29.71 | 5.58 | 15.42 | 0.13 | 3.27 | Large pellets |

| 5 | 539.74 ± 4.86 | 866.33 ± 25.73 | 9.97 | 13.13 | 0.17 | 3.28 | Large pellets |

| 10 | 607.35 ± 16.92 | 917.59 ± 25.61 | 8.44 | 11.40 | 0.14 | 3.34 | Large pellets |

| 15 | 407.11 ± 26.53 | 683.59 ± 91.27 | 6.72 | 9.33 | 0.09 | 3.36 | Pellets |

| 20 | 354.1 ± 24.31 | 504.82 ± 58.97 | 4.04 | 7.35 | 0.11 | 3.41 | Pellets |

| 30 | 270.44 ± 31.3 | 482.75 ± 21.25 | 4.07 | 8.59 | 0.08 | 3.41 | Pellets + filaments |

FPA, filter paper activity.

EG, endoglucanase.

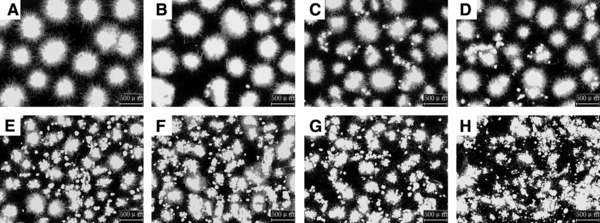

Figure 2.

Images of pellets obtained after 24 h of preculture with various concentrations of aluminum oxide microparticles. A, control (0 g/L); B, 1 g/L; C, 3 g/L; D, 5 g/L; E, 10 g/L; F, 15 g/L; G, 20 g/L; H, 30 g/L. Scale bars: 500 μm.

Although the highest sugar consumption rate was 0.17 g/(L h) of 5 g/L of aluminum oxide in medium, the concentrations of aluminum oxide did not significantly affect the sugar consumption rates for fermentation (Table 1). The maximum enzyme production rate in the FPA assay was 9.97 U/(mL h) with the addition of 5 g/L aluminum oxide; however, the maximum production rate of EG was 15.42 U/(mL h) with the addition of 3 g/L aluminum oxide. Compared with the control, the addition of aluminum oxide improved the rate of enzyme production in the FPA assay, except when 20 and 30 g/L aluminum oxide were used (Table 1). Addition of the appropriate concentration of aluminum oxide could improve enzyme production, while the addition of higher concentrations of aluminum oxide caused lower cellulase activity and decreased enzyme production rate 16.

3.2. Effect of aluminum oxide on the morphology of T. viride My during shake‐flask fermentation

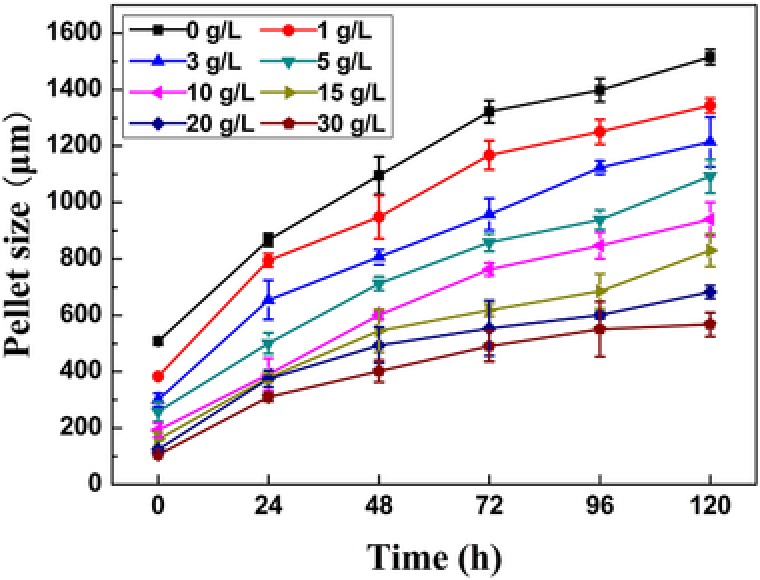

The addition of aluminum oxide microparticles to the preculture caused a substantial change in pellet diameter in the shake‐flask fermentation (Fig. 2). The addition of higher concentrations of aluminum oxide not only decreased the pellet diameters, but also increased the number of pellet‐free cells. This was clearly observed in the microscopic images (Fig. 2). The pellet diameter in the preculture medium after 24 h of fermentation at 30 g/L (105.32 μm) decreased by more than 384% compared to the control (508.41 μm; Fig. 3); thus, aluminum oxide can be used for the efficient control of T. viride My pellet diameter for cellulase production. Microbial cells were homogenously dispersed in the fermentation medium when aluminum oxide was used.

Figure 3.

Changes in mean pellet diameter over time in precultures treated with various concentrations of aluminum oxide. Error bars represent the SD, calculated based on the mean pellet diameters from triplicate experiments.

In addition, the final pH value increased with increased microparticle concentration during shake‐flask fermentation (Table 1) because of the small diameter of the pellets, which were similar to that in the filamentous type. Several previous studies have shown that the filamentous growth of Aspergillus niger is preferable for enzyme production, whereas the pelleted form is preferred for citric acid production 28, 29. Therefore, optimum pellet diameter and the high homogeneity of the broth caused by the addition of aluminum oxide increased nutrient transfer, and resulted in more effective release of the enzyme compared with that observed in the control.

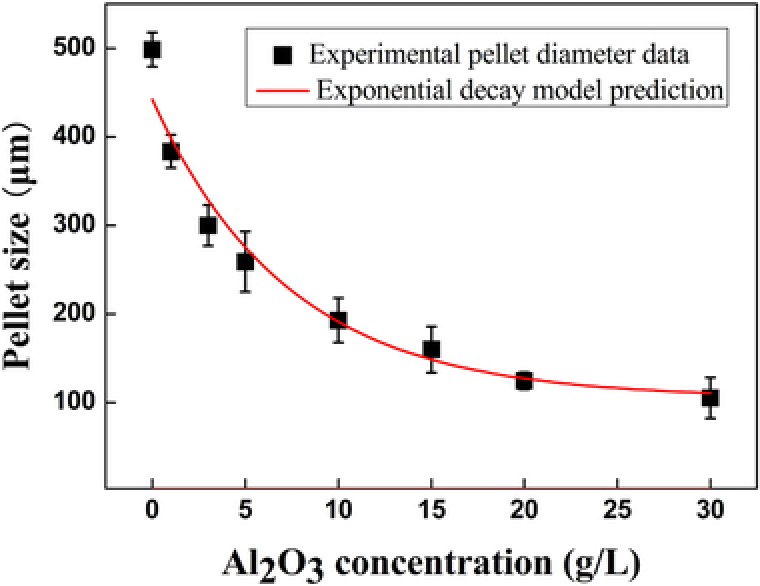

3.3. Mathematical models

The trend of pellet size change was predicted using the exponential decay model. The fitting exponential decay model is shown in Eq. (4).

| (4) |

The equation shows that y0 = 105.32 μm, A1 = 336.81, kc = 7.32 L/g, and R 2 = 0.9562. The value of R 2 indicated good correlation between the experimental and predicted values for pellet diameter by using the model.

The predicted diameters of T. viride My pellets after the addition of 0–30 g/L aluminum oxide to the preculture are shown in Fig. 4. Although the model efficiently predicted the size of the pellets after the addition of microparticles, it slightly under‐ and over‐predicted the pellet diameter at low and high concentrations of microparticles, respectively (Fig. 4). The optimal fungal morphology for product formation was observed at 10 g/L aluminum oxide (Fig. 1). At this concentration, the diameter of the T. viride My pellets was 192.9 μm after 24 h of preculture. Therefore, this model could be used to predict the best pellet diameter for optimal product formation by controlling the concentration of aluminum oxide added to the preculture. This quantified mathematical model for predicting optimal pellet diameter could improve the design and operation of fungal fermentation with optimal morphology, and advance the application of laboratory results to commercial production.

Figure 4.

Relationship between the diameter of Trichoderma viride My pellets and the concentration of aluminum oxide added to the preculture after 24 h of growth. Black squares: experimental pellet diameter values upon the addition of various concentrations of microparticles. Red line: predicted pellet diameter in the preculture, calculated using an exponential decay model.

4. Concluding remarks

In this study, the cellulase activities in FPA and EG assays increased with the addition of 10 g/L aluminum oxide compared with the control, and the size of the T. viride My pellets decreased. Additionally, the changes in pellet diameter during shake‐flask fermentation were efficiently predicted using a modified exponential decay model. This model has a high R 2 value (R 2 = 0.9562), and can be used to adjust different morphological forms by the addition of the predicted quantity of microparticles. Overall, this study showed that the addition of aluminum oxide microparticles can successfully enhance T. viride My cellulase production in shake‐flask fermentations.

Practical application

Cellulase is an important enzyme used in many fields (including food, animal feed, textile, starch processing, pulp and paper, alcohol fermentation, pharmaceuticals, and brewing industries), however, the high cost of cellulase production, especially bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass, is a major factor impeding its commercialization. In this study, morphological engineering techniques involving the addition of aluminum oxide to Trichoderma viride My precultures was used for controlling pellet size and increasing cellulase activity. The changes in pellet diameter during shake‐flask fermentation in the presence of aluminum oxide were efficiently predicted using an exponential decay model. Our findings could improve the design and operation of fungal fermentations with the most efficient morphology, and increase the application of laboratory findings for cellulase production on a commercial scale.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11305225), the key projects of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KFZD‐SW‐109), and Xizang Forage Science and Technology (2016ZDKJZC‐22).

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

5 References

- 1. Oksanen, T. , Pere, J. , Paavilainen, L. , Buchert, J. et al., Treatment of recycled Kraft pulps with Trichoderma reesei hemicellulases and cellulases. J. Biotechnol. 2000, 78, 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mach, R. L. , Zeilinger, S. , Regulation of gene expression in industrial fungi: Trichoderma. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 60, 515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gusakov, A. V. , Alternatives to Trichoderma reesei in biofuel production. Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu, Z. , Inokuma, K. , Ho, S. H. , den, Haan, R. et al., Improvement of ethanol production from crystalline cellulose via optimizing cellulase ratios in cellulolytic Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 1201–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chovau, S. , Degrauwe, D. , Bruggen, B. V. , Critical analysis of techno‐economic estimates for the production cost of lignocellulosic bio‐ethanol. Renew Sust. Energ. Rev. 2013, 26, 307–321. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuhad, R. C. , Deswal, D. , Sharma, S. , Bhattacharya, A. et al., Revisiting cellulase production and redefining current strategies based on major challenges. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2016, 55, 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Papagianni, M. , Fungal morphology and metabolite production in submerged mycelial processes. Biotechnol. Adv. 2004, 22, 189–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gonciarz, J. , Bizukojc, M. , Adding talc microparticles to Aspergillus terreus ATCC 20542 preculture decreases fungal pellet size and improves lovastatin production. Eng. Life Sci. 2014, 14, 190–200. [Google Scholar]

- 9. McIntyre, M. , Müller, C. , Dynesen, J. , Nielsen, J. , Metabolic engineering of the morphology of Aspergillus. Metabol. Eng. 2011, 103–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Driouch, H. , Sommer, B. , Wittmann, C. , Morphology engineering of Aspergillus niger for improved enzyme production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 105, 1058–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Driouch, H. , Hänsch, R. , Wucherpfennig, T. , Krull, R. et al., Improved enzyme production by bio‐pellets of Aspergillus niger: targeted morphology engineering using titanate microparticles. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012, 109, 462–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wucherpfennig, T. , Hestler, T. , Krull, R. , Morphology engineering‐Osmolality and its effect on Aspergillus niger morphology and productivity. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaup, B. A. , Ehrich, K. , Pescheck, M. , Schrader, J. , Microparticle‐enhanced cultivation of filamentous microorganisms: increased chloroperoxidase formation by Caldariomyces fumago as an example. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2001, 99, 491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Germec, M. , Yatmaz, E. , Karahalil, E. , Turhan, I. , Effect of different fermentation strategies on b‐mannanase production in fed‐batch bioreactor system. Biotech. 2017, 7, 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang, S. Y. , Jiang, B. L. , Zhou, X. , Chen, J. H. et al., Study of a high‐yield cellulase system created by heavy‐ion irradiation induced Mutagenesis of Aspergillus niger and mixed fermentation with Trichoderma reesei. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0144233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yatmaz, E. , Yatmaz, E. , Karahalil, E. , Germec, M. et al., Controlling filamentous fungi morphology with microparticles to enhanced β‐mannanase production. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2016, 39, 1391–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu, X. X. , Liu, Y. , Cui, Y. X. , Cheng, Q. Y. et al., Measurement of filter paper activities of cellulase with microplate‐based assay. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2016, 23, 93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ghose, T. K. , Measurement of cellulase activities. Pure Appl. Chem. 1987, 59, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu, W. , Hildebrand, A. , Kasuga, T. , Xiong, X. et al., Direct cellobiose production from cellulose using sextuple beta‐glucosidase gene deletion Neurospora crassa mutants. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2013, 52, 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abramoff, M. D. , Magalhães, P. J. , Ram, S. J. , Image processing with Image J. Biophoton. Int. 2004, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller, G. L. , Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lawford, H. G. , Rousseau, J. D. , Comparative‐study of glucose conversion to ethanol by Zymomonas mobilis and a recombinant Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Lett. 1993, 15, 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hayyat, M. U. , Ali, S. , Kinetics of an Extracellular β‐D‐Fructofuranosidase Fructohydrolase production from a Derepressed mutant of Saccharomyces carlsbergensis and parameter significance analysis by 2‐factorial design. Pakistan J. Zool. 2013, 45, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar]

- 24. John, D. A. , Jerry, M. M. , Charles, A. M. , Predicting long‐term patterns of mass loss, nitrogen dynamics, and soil organic matter formation from initial fine litter chemistry in temperate forest ecosystems. Can. J. Bot. 1990, 68, 2201–2208. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tronchoni, J. , Gamero, A. , Arroyo‐López, F. N. , Differences in the glucose and fructose consumption profiles in diverse Saccharomyces wine species and their hybrids during grape juice fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 134, 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coban, H. B. , Demirci, A. , Turhan, I. , Microparticle‐enhanced Aspergillus ficuum phytase production and evaluation of fungal morphology in submerged fermentation. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 38, 1075–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karahalil, E. , Demirel, F. , Evcan, E. , Germec, M. et al., Microparticle‐enhanced polygalacturonase production by wild type Aspergillus sojae. Biotech. 2017, 7, 361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steel, R. , Lentz, C. P. , Martin, S. M. , A standard inoculum for citric acid production in submerged culture. Can. J. Microbiol. 1954, 1, 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kristiansen, B. , Bullock, J. D. , Developments in industrial fungal biotechnology, in: Smith J. E., Berry D. R., Kristiansen B. (Eds.), Fungal Biotechnology, Academic Press, London: 1988, pp. 203–223. [Google Scholar]