Abstract

The reactor systems used for microbial electrosynthesis, i.e. bioelectrochemical systems for achieving bioproduction so far reported in literature are relatively small in scale and highly diverse in their architecture and modes of operation. The often diverging requirements of the electrochemical and the biological processes and the interdisciplinarity of the field make the engineering of these systems a special challenge. This has led to multiple, differently optimized approaches of reactor vessels, designs and operating conditions making standardization and normalization or even a systematic engineering almost impossible. Overcoming this lack of standardization, scalability and knowledge‐driven engineering is the driving force for this work introducing an upgrade kit for bioreactors transforming these reversibly to bioelectroreactors. The prototypes of the bioreactor upgrade kit were integrated with commercial bioreactor (fermentor) systems and performances compared to a classic, small‐scale bioelectrochemical glass cell system. The use of the upgrade kit allowed interfacing with the existing infrastructure of the conventional bioreactors for growing electroactive microorganisms in pure culture conditions, with the added electrochemical control and further process monitoring. The results of growing Shewanella oneidensis MR‐1 clearly show that these systems can be used to control, monitor, and scale microbial bioelectrochemical processes, providing better resolution of the data for the tested experimental conditions.

Keywords: Bioelectrochemical systems, Bioelectrosynthesis, Bioelectrotechnology, Electrobiotechnology, Microbial electrochemical technology

Abbreviations

- CE

counter electrode

- DEET

direct extracellular electron transfer

- LB

lysogenic broth

- MEET

mediated extracellular electron transfer

- RE

reference electrode

- SHE

standard hydrogen electrode

- VVM

volume of gas per volume of liquid per minute

- WE

working electrode

1. Introduction

Bioelectrotechnology or electrobiotechnology 1 combines the flow of electric current and transformations for the synthesis and upgrading of chemicals based on biological redox reactions. Thereby electrons are transferred between an electrode and a biological moiety—being referred to as microbial or enzymatic electrocatalyst—enabling the desired transformation by different mechanisms. In the following work, an upgrade kit for conventional bioreactors is introduced 2, 3 and exemplarily demonstrated on a microbial electrochemical process that can be used for enzymatic electrochemical synthesis and other microbial electrochemical technologies as well.

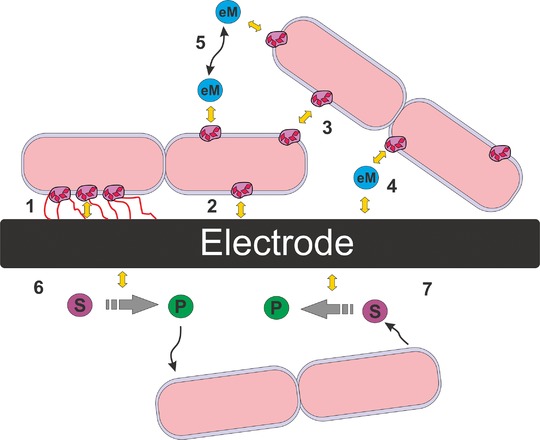

Figure 1 depicts the possible modes of interactions of electrodes and microorganisms. From the engineering perspective three principle cases can be distinguished (i) biofilm processes, where the microbial electrocatalyst is physically connected to the electrode and hence based purely on direct extracellular electron transfer (Fig. 1 modes 1 to 3), (ii) planktonic processes, where the microbial electrocatalyst is suspended in solution and the transduction of electrons is based on mediated extracellular electron transfer as well as direct extracellular electron transfer (Fig. 1, modes 1–5), and (iii) planktonic processes where the microbial moiety does not perform an immediate interaction with the electrode. The connection of electrochemical and microbial transformation is more indirect and based on abiotic reactions that can either provide the microorganisms with an in situ synthetized product that can be uptaken into the microbial metabolism (Fig. 1, mode 6), or start from an extracellular microbial exudate that is used as a substrate for the abiotic electrochemical synthesis (Fig. 1, mode 7). All cases face different prerequisites and engineering needs; however they are bound to the same objective: setting up an economically viable process and thus the need for optimized space time yields, high product titers, selectivity, etc. 6.

Figure 1.

Interfacing microorganisms and electrodes: modes of microbial extracellular electron transfer—objects placed between inner and outer membrane represent bacterial surface‐exposed cytochromes. Nanowires are presented in red. Yellow arrows represent electron transfer steps. Mechanisms 1–3 correspond to direct extracellular electron transfer (DEET), where electrons are transferred directly to the exterior of the cells through the periplasmic cytochrome pool and/or nanowires: (1) using nanowires attached to the electrode surface, (2) DEET by contact of surface exposed cytochromes with the electrode. (3) interspecies DEET by contact of the surface exposed cytochromes between bacteria and/or nanowires; mechanisms 4 and 5 represent mediated extracellular electron transfer (MEET), where a reversible redox mediator (eM) is reduced (or oxidized) by bacteria and transported (via convection and diffusion—black arrows) through the extracellular environment, to the next electron acceptor/ donor. (4) MEET, where the mediator is reduced (or oxidized) by bacteria and oxidized (or reduced) by contacting with the electrode surface, (5) interspecies MEET, where the mediator is reduced (or oxidised) by one bacterial species and again oxidized (or reduced) by another bacteria, see for more details.4, 5. (6 and 7) Abiotic electrochemical reactions: the microbial electron donor/acceptor is provided by/to an abiotic electrochemical reaction; P and S are, respectively, the products(s) and substrate(s) of the abiotic electrochemical reactions.

The proposed product spectrum for microbial electrosynthesis is almost infinite as all redox reactions can in principle be interfaced to electrodes. The products of bioelectrosynthesis shown so far range from hydrogen 7, methane 8, and acetic acid, to more complex molecules such as 1,3‐propanediol 9 and 2‐oxobutyrate 10 (see Table 1). Based on the example of lysine production from sucrose it was shown that microbial electrosynthesis has a realistic market potential 6.

Table 1.

Representative examples of microbial electrosynthesis, adapted from 6

| Products | Electrode/reactor | Reactor volume anode/cathode (L) | Microbial electrocatalyst | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | Graphite felt/two‐chamber reactor | 0.250/0.250 | Naturally selected cultures from wastewater (biocathode) | 20 |

| NaOH | Graphite felt, stainless steel mesh/ lamellar reactor | 1.02/0.61 | Naturally selected cultures from brewery wastewater (biocathode) | 21 |

| CH4 | Fiber brush anode, carbon cloth cathodes/single‐chamber MEC | 0.250/0.250 | Microbial community from methane producing MEC | 7 |

| CH3COOH, CH3CH2COCOOH | Unpolished graphite sticks/H‐cell | 0.200/0.200 | Sporomusa ovata | 9 |

| CH3COOH, CH3CH2COCOOH | Unpolished graphite sticks/H‐cell | 0.200/0.200 | Clostridium ljungdahlii, S. sphaeroides, S. silvacetica, C. aceticum, M. thermoacetica | 10 |

| CH4, CH3COOH, H2 | Graphite granules/glass chambers | 0.150/0.150 | Microbial community from brewery waste water | 22 |

| CH3COOH, C2H5COOH C3H7COOH | Neutral red activated graphite felt/adapted bioreactor | 0.05/0.5 | Clostridium acetobutylicum KCTC1037 (with neutral red as mediator) | 23 |

| CH3COOH | NanoWeb RVC/three‐electrode two‐chamber cell | 0.010/0.25 | Microbial consortium from natural environment mixed with engineered anaerobic systems culture | 24 |

| C2H6O | Carbon fiber electrode/three electrode cell with membrane | 0.012 | Engineered S. oneidensis | 19 |

| C5H9NO4 | Platinum/shake flask | 0.040 | Brevibacterium flavum No. 2247 (with neutral red as a mediator) | 25 |

| C3H8O2, C3H6O2, C5H10O2 | Graphite plates/cubic two‐chamber bio‐reactor | 0.200/0.200 | Microbial consortium | 26 |

| CH3COOH, C3H6O2 | Platinum electrodes/standard three‐electrode cell | 0.005/0.1 | Propionibacterium freudenreichii (with mediator CoS) | 27 |

In contrast to their promising potential bioelectrotechnological synthesis are still far from entering the market. One major drawback is based on the missing standards and comparability in the field making an assessment of different studies on the same process as well as the benchmarking of bioelectrotechnological processes versus established processes so far not feasible. One major reason is based on the lack of comparable reactor systems, which also hampers a knowledge‐driven process engineering 11. Reactor systems that can be found in literature for bioelectrochemical synthesis, being also known as bioelectrochemical systems, are most often custom‐made, small‐scale (<1 L) designs (see Table 1), most of them are adapted from microbial fuel cell like wastewater treatment systems. Furthermore, these reactors are rarely equipped with sufficient process monitoring and process control devices 6. Consequently, standardization not only of data analysis and acquisition 6, 12 but also of the infrastructure used seems essential to pave the way of microbial electrosynthesis from research to application level.

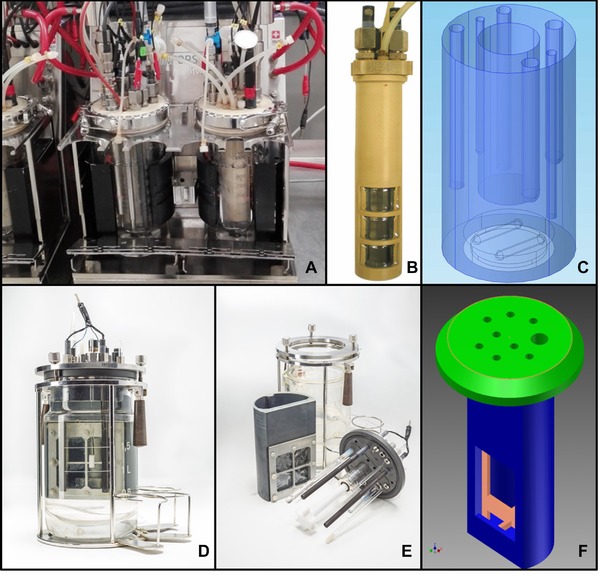

This gap between basic studies and process development up to pilot scale can be minimized by the use of a common reactor technology platform. Here, we propose such a platform based on an upgrade kit for conventional lab‐scale bioreactors to build bioelectroreactors (Fig. 2). Using this upgrade kit, existing bioreactor systems (fermentors) can be reversibly repurposed to allow performing (bio)electrochemical processes. Thereby, the benefits of the conventional bioreactor systems, the longstanding workhorse of biotechnology, can be utilized for research and development of bioelectrotechnological processes. Using this integrated system electrochemical parameters can be studied and controlled while at the same time the bioreactor infrastructure enables monitoring and control of common process variables (e.g. pO2, pH, and temperature). We are confident that bioelectroreactors will allow in future, not only a high level of standardization and systematic development as well as scaling, but also cross‐comparison and benchmarking of bioelectrosynthesis. Here, we provide proof of concept that the bioreactor upgrade kit is compatible with standard, pure culture cultivation methods and electrochemical monitoring of the model organism Shewanella oneidensis MR‐1.

Figure 2.

Breadboard prototype pictures and designs. (A–C) Pictures of bioreactor upgrade kit A, for an Infors HT system. (A) Bioelectroreactors in operation; (B) Picture of the chamber dividing inlay of upgrade kit A; (C) CAD design representing the liquid volume and stirrer of upgrade kit A. (D–F) Pictures of bioreactor upgrade kit B, for a Sartorius Biostat B system. (D) Bioelectroreactors with upgrade kit B (©André Künzelmann, UFZ Leipzig, Germany). (E) Expanded picture showing the components of upgrade kit B (©André Künzelmann, UFZ Leipzig, Germany); (F) CAD sketch of a scaled version of upgrade kit B.

Shewanella oneidensis MR‐1 is one of the model organisms exhaustively studied for its extracellular electron transfer capabilities 13. It is a Gram negative, rod shaped, flagelated proteobacteria, facultative anaerobe, and resistant to low temperatures and mild salinity. It possesses capacity to reduce both inorganic and organic compounds like no other known microorganism in both anaerobic and aerobic conditions. It can either form biofilms with electron conductive nanowires, or thrive as a planktonic organism, producing its own extracellular electron transfer mediators 14, 15. It can be considered as possessing a Swiss Army pocket knife like metabolism unrivaled by any other metal respiring microorganism 16. Its genome is fully sequenced 17 and its phylogenetic proximity to E. coli means genetic manipulation and associated tools are being quickly adapted, and some are already developed to be implemented and used 18, 19.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Classic electrochemical cell

For the comparison with the bioelectroreactors, electrochemical cells based on three‐neck round‐bottom flasks modified from 28 were used. Graphite rod working electrode (WE, 9.25 cm2) and counter electrode (CE, 15 cm2) were hosted in membrane separated WE chamber with a volume of 100 mL and the CE chamber with 10 mL and the WE chamber hosting a reference electrode (RE) and stirrer. The separation between the electrode chambers was accomplished by a circular ion exchange membrane crimped to a custom‐made glass tube hosting the, by then, spatially separated but ionically connected CE. At the WE, the reaction under study, here the extracellular electron transfer of Shewanella, takes place, while at the CE the necessary counter reaction, here the hydrogen evolution reaction, proceeds.

2.2. Design and fabrication of the upgrade kits

The set of reactors used in this work were equipped with breadboard prototypes of an upgrade kit designed for the integration into existent conventional bioreactors 2, 3 (Fig. 2). The upgrade kit is composed of three principal parts: an optimized/adapted lid, attached to an inlay, equipped with an ion exchange membrane, and a set of anodes and cathodes. The lid and inlay parts are made of a nonconductive material—here polyether ether ketone—‐that needs to be autoclavable for pure culture studies. The lid harbors all standard connectors and screws of bioreactor systems allowing connecting and mounting standard sensors (e.g. pH, pO2, temperature), gas inlets and outlets, acid/base inlets for pH control, and sampling and feeding ports. Additionally, electrode inlet ports (here two for each WE and CE and one for the RE) to allow electrochemical control and monitoring are introduced. The inlay possesses a lateral opening (window), where an ion exchange membrane is fixed, that divides the liquid volume of the bioreactor vessel in two compartments: the WE compartment hosting the WE and the RE, and the CE compartment hosting the CE. The electrodes used in this study were polycrystalline graphite rods, a geometrically simple standard used in numerous laboratories. Certainly, other electrode materials as well as electrode geometries can be easily adapted and used. Based on the bioreactor platform, design differences between upgrade kits occur. In Fig. 2, two different bioelectroreactor prototypes are shown: upgrade kit A (Fig. 2A–C), was made for upgrading the 1 L glass vessels reactor (Infors HT Multifors system, Switzerland), where the stirrer is magnetically driven from the bottom of the reactor (Fig. 1C), and upgrade kit B (Fig. 2F) built for upgrading a 2 L glass vessel reactor (Sartorius Biostat B, Germany), with a top driven stirrer motor and stirrer shaft. This difference in the original stirring elements resulted in a different inlay design: For the bioelectroreactor with upgrade kit B the working volume (900 mL) occupies ∼2/3 of the circular section of the vessel and is enclosed by the inlay with the stirrer shaft being centralized relatively to the inlay, but offset relatively to the lid. The original steel stirrer and stirrer shaft were replaced by a 6‐blade Rushton turbine impeller, made of polytetrafluoroethylene (Fig. 2E). The volume outside the inlay (1 L) serves as CE chamber. In case of the bioelectroreactor with upgrade kit A the inlay position is central in the vessel and lid, and encloses the CE chamber (150 mL). Stirring of the outer WE chamber (750 mL) is achieved using a custom‐made magnetic stirrer on the bottom of the vessel, driven by the original magnetic drive of the reactor system (Fig. 2C). Experiments shown in this work were performed with bioelectroreactors using upgrade kit A, where in each reactor the WE was cut to display 76.97 cm2 geometric surface area, and the WE chamber volume was 750 mL.

The introduction of electrochemical control in the reactors requires the introduction of respective equipment: for lab‐scale studies and to be characterized processes potentiostats/glavanostats are preferable (as used in this study); for larger scales, well‐known processes and especially routine operation DC power sources will be sufficient.

2.3. Case study experiments

2.3.1. Chemicals and cultivations

All chemicals were of at least analytical grade. For all experiments deionized water (Millipore) was used. All potentials are provided versus standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) by conversion from Ag/AgCl (sat. KCl, +0.197 V vs. SHE).

Shewanella oneidensis MR‐1, obtained from Zentrum für Angewandte Geowissenschaften (Universität Tübingen, Germany), was maintained in glycerol cryostocks at −80°C. The cryostock culture was regularly streaked on to lysogenic broth (LB) agar plates 29, and grown overnight (16–18 h) at 30°C.

Precultures used for all experiments consisted of inoculating 150 mL LB growth medium with bacteria derived from an isolated single colony of a fresh LB agar plate, and incubating in an Erlenmeyer flask (500 mL) for 24 h at 30°C, 150 rpm in an orbital shaker. Prior to experiments optical density was measured at 600 nm (OD600), and precultures diluted to a final OD600 of 0.2. Sterile M4 minimal media was used in all experiments 30 containing 50 mM l‐lactate as substrate and electron donor, respectively.

2.3.2. Bioelectroreactor setup and operation

WE and CE were made from crystalline graphite rods (CP‐2200 quality, CP‐Handels GmbH, Wachtberg, Germany) with 10 mm Ø and 50 cm in length. RE (Ag/AgCl sat. KCl, Sensortechnik SE11, Meinsberg, Germany) were stored in a saturated KCl solution, and rinsed extensively with water before use (for the classic bioelectrochemical cells), or dipped in a 70% ethanol solution for 24 h before insertion in the bioelectroreactors. The ion exchange membranes for separating the electrode compartments (FKE, Fumatech GmbH, Bissingen, Germany) were either extensively soaked and washed in deionized water—for the classic bioelectrochemical cell experiments—or autoclaved in custom‐made, sealed, steam‐tight autoclaving bags at 121°C for 20 min—for experiments in bioelectroreactors.

WEs in the systems were poised at a potential of +397 mV versus SHE with recording of the current every 60 s using a multipotentiostat system (MPG‐2, Bio‐Logic, Claix, France) for classic bioelectrochemical cells and a multipotentiostat (VSP, Bio‐Logic Claix) for the bioelectroreactors. Every 6 h cyclic voltammograms were acquired with 1 mV s−1 scan rate, between +397 mV and −403 mV versus SHE (two consecutive scans per time). Temperature was controlled at 30 ± 1°C using a thermostatic incubator for the classic bioelectrochemical system and the integrated heating/cooling control for the bioelectroreactors, respectively. The equipment of the classic bioelectrochemical cells was washed and disinfected with Wofasteril E 400 (Kelsa GmbH, Bitterfeld‐Wolfen, Germany) followed by exhaustive rinsing with deionized water and drying at 60°C before using, whereas all the components of the bioelectroreactors (with exception of the RE) were autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min. The autoclaved parts and the ethanol‐sterilized REs were assembled in a laminar flow hood.

All experiments were conducted in triplicates for each condition. Three different aeration and stirring combinations were used in both classic bioelectrochemical cells and bioelectroreactors:

Cultivation condition 1—Anaerobic: The cultures were kept under continuous gassing using filtered, humidified nitrogen throughout the experiment (65 h). The gas flow rate was kept constant at 0.5 vvm (vvm: gas volume per WE chamber volume per minute). No mechanical stirring was introduced for this condition.

Cultivation condition 2—Aerated: The cultures were aerated with filtered, humidified compressed air at 0.5 vvm for the first 25 h. Then cultures were supplemented with lactate back to 50 mM, and gassing was changed to filtered humidified nitrogen for the remaining experiment time. No mechanical stirring was introduced in for this condition.

Cultivation condition 3—Aeration and agitation: The same treatment as condition 2 was applied, where additionally the media (anolyte) was mechanically stirred at 200 rpm.

2.3.3. Chemical analysis and calculations

In all cultivations liquid samples (1 mL for classic bioelectrochemical cells, 7 mL for bioelectroreactors, from which the first 5 mL was discarded) were drawn periodically. OD600 was determined (Amersham Pharmacia Ultrospec 1100 Pro UV, Amersham, UK) and samples were analyzed by HPLC (Shimadzu Cooperation, Japan) and lactate and acetate concentrations calculated based on calibration curves. Prior to HPLC analysis the sample was centrifuged in a microcentrifuge (MiniSpin, Eppendorf, Wesseling‐Berzdorf, Germany) for 5 min at room temperature at 13 000 rpm. HPLC analysis was performed using a HiPlex H column 300 × 7.7 mm (Agilent Technologies, Inc., CA, USA) with a SecurityGuard Cartidge Carbo‐H 4 × 3.0 mm precolumn (Phenomenex, USA) and refractive index detector (RID‐10A, Shimadzu Cooperation). The isocratic liquid phase was 0.01 N sulfuric acid at a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1 and the column oven temperature was set to 50°C.

All data from the triplicate measurements obtained (current, concentrations, optical densities, acetate and lactate concentrations) was averaged for each time and condition, and confidence intervals at 95% confidence calculated using the standard deviation and Student‐t probability distributions for n = 3 31.

Current densities were calculated by dividing the obtained current by the anode geometric area used in each of the systems. Coulombic efficiencies were determined by comparison of the total amount of electrons produced in each system based on the amount of educt (lactate) or product (acetate) cumulatively consumed or produced, respectively, assuming a theoretical yield of four electrons per mole of either educt or product turnover.

3. Results and discussion

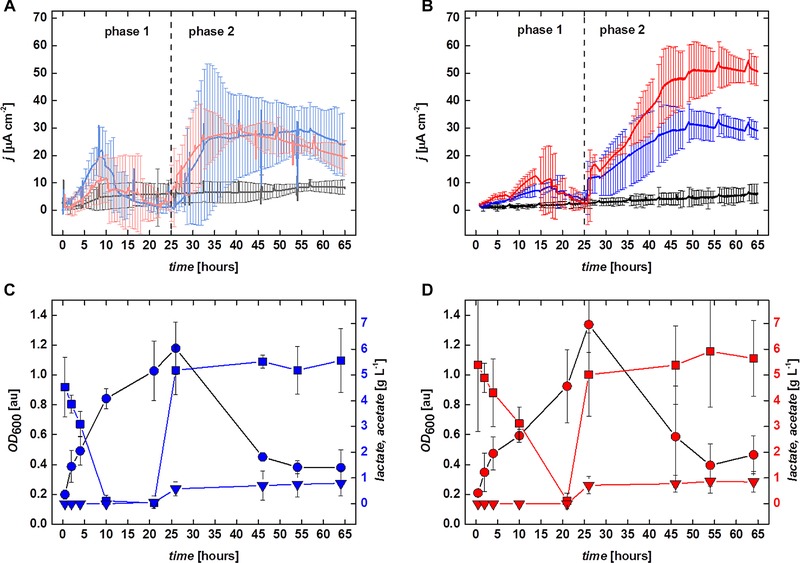

Cultivation of S. oneidensis MR‐1, a well characterized electroactive microorganism, was used for providing a comparative example between the use of classic bioelectrochemical cells and the upgrade kit A for bioreactors. Figure 3A and B shows the resulting averaged chronoamperograms, i.e. current density as function of time, obtained using the classic bioelectrochemical cells (Fig. 3A) and bioelectroreactors (Fig. 3B), respectively. Based on the experimental design (see Section 2.3.2) the figures can be divided in two distinct phases: phase 1 (0–25 h) where for cultivation conditions 2 and 3 oxygen was supplied to the systems by aeration with compressed air, and where cultivation condition 1 served as a strict anaerobic control (Supporting information, Fig. S1 and S2 depict the detail of Fig. 3A and B for this phase, respectively), and phase 2 (25–65 h) where previous aeration of the systems with compressed air was changed for nitrogen creating anaerobic conditions. (Supporting information, Fig. S3 and S4 depict the detail of Fig. 3A and B for this phase respectively).

Figure 3.

Results obtained growing S. oneidensis MR‐1. (A and B) Average current densities obtained for the three conditions studied in classic bioelectrochemical cells (A) and bioelectroreactors (B), respectively. (A) cultivation condition 1,

cultivation condition 1,  cultivation condition 2,

cultivation condition 2,  cultivation condition 3; (B)

cultivation condition 3; (B)  cultivation condition 1,

cultivation condition 1,  cultivation condition 2,

cultivation condition 2,  cultivation condition 3. Corresponding color error bars show the 95% confidence interval calculated from the triplicate experimental measurements. (C and D) Average lactate (

cultivation condition 3. Corresponding color error bars show the 95% confidence interval calculated from the triplicate experimental measurements. (C and D) Average lactate ( ,

,  ) and acetate (

) and acetate ( ,

,  ) concentrations, and OD600 (

) concentrations, and OD600 ( ,

,  ) obtained from triplicate experimental measurements for the cultivation of S. oneidensis MR‐1 in bioelectroreactors, using cultivation condition 2 (C), and cultivation condition 3 (D), respectively. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval calculated for each average data point.

) obtained from triplicate experimental measurements for the cultivation of S. oneidensis MR‐1 in bioelectroreactors, using cultivation condition 2 (C), and cultivation condition 3 (D), respectively. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval calculated for each average data point.

The statistical confidence intervals calculated for the chronoamperometric data shown in Fig. 3A, obtained using classic bioelectrochemical cells, imply that clear distinction between the current densities obtained for the different conditions can only be made from approximately 40 h onwards, and only for cultivation condition 1 versus cultivation conditions 2 and 3. The chronoamperometric data from the last two conditions was not differing significantly. In contrast, when using the bioelectroreactors harbouring the upgrade kit A and applying the analogous conditions, shows well resolved confidence intervals for the chronoamperometric data between all cultivation conditions and already for early stages of cultivation. Differences between all three conditions are only insignificant in phase 1 from 15 to 25 h, whereas in phase 2, conditions 2 and 3 can only be deemed different from each other from 46 h onwards, but remain different from condition 1 for the complete duration of this phase. Additionally, using the bioelectroreactor systems allows to measure online routine parameters such as pH and pO2 relative to air saturation. However, for every specific application the possible effect of the applied electric field on sensor components must be addressed, and glavanic insulation introduced if required. In the present study, the applied electrochemical conditions had no effect during step‐wise chronoamperometry (data not shown) and even voltammetric techniques could be performed without interfering with the online measurements (see cyclic voltammograms—Supporting information, Fig. S5 and S6, and online measured data, Supporting information, Fig. S7). The routine measurement of these parameters in classical bioelectrochemical cells is often very difficult to achieve. Therefore, in addition to the lower process variability, monitoring and steering of bioelectrochemical processes can be significantly improved in bioelectroreactors.

These findings already demonstrate the better suitability of the upgrade kit equipped bioreactor system for comparison of the electrochemical data obtained using the experimental conditions employed in this study.

Overall, maximum current densities obtained in this study were around 30 μA cm−2 (being well in line with results obtained for this model organism, e.g. 32), but a significantly higher maximum current density of 50 μA cm−2 was obtained using cultivation condition 3 in the bioelectroreactor system. This was most likely due to the introduction of consistent convective movement by improved stirring—an effect needing further experimental and theoretical evaluation. The improved overall mass transfer inside the agitated reactor for cultivation condition 3 also increased the collision probability of electron carrying molecules (cellular cytochromes and/or extracellular riboflavin mediators) with the anodes. Coulombic efficiencies of the electron transfer from the microorganisms to the electrodes in both classic and bioelectroreactor systems, in the anaerobic phase 2 were between 7.30 ± 2.17 % and 13.08 ± 1.84%, averaging 10.19 ± 2.84%. Both current densities and coulombic efficiencies obtained in this work were found consistent with values described for similar growth conditions of S. oneidensis MR‐1 32.

All cultivations using condition 1 in phase 1 exhibited low anodic current of ∼5.1 μA cm−2 in the classic bioelectrochemical cells and ∼2.5 μA cm−2 in the bioelectroreactors (Fig. 3A and B), indicating low but viable metabolic activity of the bacterial cells. For cultivations using condition 1 during phase 1 OD600 is remaining near the initial inoculation value of 0.2 in both systems, indicating that for strict anaerobic cultivation a measurable increase in the number of planktonic cells of S. oneidensis MR‐1 as well as lactate consumption could not be obtained in the time frame of our experiments.

When comparing both systems using cultivation conditions 2 and 3, during phase 1, planktonic growth of the bacteria was observed as expected, with OD600, increasing from its initial value significantly and averaging at OD600 = 1.1 ± 0.2 in the classic bioelectrochemical cells, and OD600 = 1.2 ± 0.2 and OD600 = 1.3 ± 0.2, in the bioelectroreactors. This growth is accompanied by the complete consumption of the substrate, lactate for these two conditions.

Figure 3C (condition 2) and D (condition 3) shows in detail the lactate consumption and OD600 in the bioelectroreactor systems. In the initial aerobic phase 1, a difference in OD600 between the bioelectroreactors that were not (Fig. 3C) and those that were (Fig. 3D) subjected to mechanical agitation was observed: S. oneidensis MR‐1 cells grew and consumed most of the lactate 10 h earlier in the reactors without agitation, than in those where agitation was set at 200 rpm. At the same time the fast growing cells yielded lower current densities and total current in the nonagitated reactors, than in the agitated ones (Fig. 3B, Supporting information, Fig. S2). Interestingly, in these conditions pO2 as measured in the bioelectroreactors was around 1% for the duration of the experiments. This result may suggest that with the aeration conditions used, the metabolism of the bacteria was probably mixed, i.e. split between aerobic and anaerobic as also suggested by 16. The utilization of the anaerobic metabolic pathways by the bacteria was promoted mainly due to the more often discharge of electrons from the cytochrome “capacitor” pool onto the reactor electrodes. One now may speculate that the more electrons were removed from the cells through this path, the higher the fraction of the metabolism was in anoxic mode, which is reflected in slower overall planktonic cell growth rate and substrate consumption, as well as higher current production. This, however, needs further evaluation.

4. Concluding remarks

In this study we have compared the growth of S. oneidensis MR‐1, a well‐known and well characterized electroactive microorganism, in two different reactors setups: The classic electrochemical three‐neck‐round‐bottom glass cell and a bioreactor equipped with an upgrade kit termed bioelectroreactor 2, 3. The classic electrochemical cell was used as typical representative (100 mL anolyte, 0.092 cm2 mL−1). The bioelectroreactor systems used were larger in scale (750 mL anolyte, 0.102 cm2 mL−1) operated at sterile conditions and allowed the monitoring of further process parameters like pH and pO2. The performance of the bioelectroreactors was clearly more reproducible (i.e. yielding more consistent results) and allowing differentiating all experimental conditions used.

Bioelectroreactors were allowing further distinguishing growth and current production by S. onedensis MR‐1 for only (seemingly) slightly different mass‐transfer conditions, which is not possible in classical electrochemical cells and needing further investigation. The application example clearly shows that bioelectroreactors can be used to engineer microbial electrochemical processes and technologies being based on plethora of different so far known (see e.g. Table 1), as well as to be discovered electroactive microorganisms. Hence the introduced bioelectroreactors can become a platform technology that also allows benchmarking to competing processes in biotechnology.

Practical application

An upgrade kit for bioreactors (fermentors) enabling these to be used for bioelectrotechnology is introduced. This upgrade kit can be tailored to different conventional bioreactors systems and scales, and is reversibly mounted and suitable for a plethora of application conditions (e.g. environmental and biotechnological operation). The resulting bioelectroreactors are introduced on example of cultivating the electroactive model organism Shewanella oneidenis MR‐1. In contrast to classical electrochemical cells, bioelectroreactors can use the monitoring and controlling units of bioreactors completely, and hence provide further insights within a standardized system for the cultivation of microorganisms. Based on the demonstrated upgrade kit it will be not only possible to study and engineer a specific bioelectrotechnological application, it will also allow the comparison across studies and laboratories (being not possible to date) enabling standardization and knowledge‐driven engineering and its benchmarking to conventional processes.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

Peter Portius and co‐workers from the workshop of the UFZ Leipzig are acknowledged for their help building the upgrade kits. Sebastian Engel is acknowledged for his help in sterile preparation and sampling of the bioelectroreactors.

F.H. acknowledges support by the BMBF (Research Award “Next generation biotechnological processes ‐ Biotechnology 2020+”) and the Helmholtz‐Association (Young Investigators Group). This work was supported by the Helmholtz‐Association within the Research Programme Renewable Energies.

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

5 References

- 1. Schröder, U. , Harnisch, F. , Angenent, L. T. , Microbial electrochemistry and technology: Terminology and classification. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 513–519. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gimkiewicz, C. , Hunger, S. , Stang, C. , Rosa, L. F. M. et al., Aufrüstset für Bioreaktoren zur Durchführung der mikrobiellen Bioelektrosynthese. Biospektrum 2015, 21, 453–454 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harnisch, F. , Hunger, S. , Zehnsdorf, A. , Beyer, D. et al., Expansion kit for bioreactors used for performing microbial bio‐electrosynthesis . German patent DE102013224673A1, International patent WO2015082490 A1, PCT/EP2014/076293, 2013.

- 4. Sunil, C. H. , Patil, A. , Gorton, L. , Electron transfer mechanisms between microorganisms and electrodes in bioelectrochemical systems. Bioanal. Rev. 2012, 4, 159–192. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schröder, U. , Anodic electron transfer mechanisms in microbial fuel cells and their energy efficiency. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 2619–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harnisch, F. , Rosa, L. F. M. , Kracke, F. , Virdis, B. et al., Electrifying white biotechnology: Engineering and economic potential of electricity‐driven bio‐production. Chemsuschem 2015, 8, 758–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng, S. , Xing, D. , Call, D. F. , Logan, B. E. , Direct biological conversion of electrical current into methane by electromethanogenesis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 3953–3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhou, M. , Chen, J. , Freguia, S. , Rabaey, K. et al., Carbon and electron fluxes during the electricity driven 1,3‐propanediol biosynthesis from glycerol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 11199–11205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nevin, K. P. , Woodard, T. L. , Franks, A. E. , Summers, Z. M. et al., Microbial electrosynthesis: Feeding microbes electricity to convert carbon dioxide and water to multicarbon extracellular organic compounds. mBio 2010, 1, (e00103‐10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nevin, K. P. , Hensley, S. A. , Franks, A. E. , Summers, Z. M. et al., Electrosynthesis of organic compounds from carbon dioxide is catalyzed by a diversity of acetogenic microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 2882–2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krieg, T. , Sydow, A. , Schröder, U. , Schrader, J. et al., Reactor concepts for bioelectrochemical syntheses and energy conversion. Trends Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harnisch, F. , Rabaey, K. , The diversity of techniques to study electrochemically active biofilms highlights the need for standardization. Chemsuschem 2012, 5, 1027–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hau, H. H. , Gralnick, J. A. , Ecology and biotechnology of the genus Shewanella. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 61, 237–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thormann, K. M. , Saville, R. M. , Shukla, S. , Pelletier, D. A. et al., Initial phases of biofilm formation in Shewanella oneidensis MR‐1. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 8096–8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marsili, E. , Baron, D. B. , Shikhare, I. D. , Coursolle, D. et al., Shewanella secretes flavins that mediate extracellular electron transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2008, 105, 3968–3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sturm, G. , Richter, K. , Doetsch, A. , Heide, H. et al., A dynamic periplasmic electron transfer network enables respiratory flexibility beyond a thermodynamic regulatory regime. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1802–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heidelberg, J. F. , Paulsen, I. T. , Nelson, K. E. , Gaidos, E. J. et al., Genome sequence of the dissimilatory metal ion‐reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002, 20, 1118–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ross, D. E. , Flynn, J. M. , Baron, D. B. , Gralnick, J. A. et al., Towards electrosynthesis in shewanella: Energetics of reversing the mtr pathway for reductive metabolism. PloS One 2011, 6, e16649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Flynn, J. M. , Ross, D. E. , Hunt, K. A. , Bond, D. R. et al., Enabling unbalanced fermentations by using engineered electrode‐interfaced bacteria. mBio 2010, 1, (e00190‐10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rozendal, R. A. , Jeremiasse, A. W. , Hamelers, H. V. , Buisman, C. J. , Hydrogen production with a microbial biocathode. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 629–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rabaey, K. , Butzer, S. , Brown, S. , Keller, J. et al., High current generation coupled to caustic production using a lamellar bioelectrochemical system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 4315–4321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marshall, C. W. , Ross, D. E. , Fichot, E. B. , Norman, R. S. et al., Electrosynthesis of commodity chemicals by an autotrophic microbial community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 8412–8420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Young‐Jeon, B. , Jung, I. L. , Park, D. H. , Conversion of carbon dioxide to metabolites by Clostridium acetobutylicum KCTC1037 cultivated with electrochemical reducing power. Adv. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 332–339. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jourdin, L. , Freguia, S. , Donose, B. C. , Keller, J. , Autotrophic hydrogen‐producing biofilm growth sustained by a cathode as the sole electron and energy source. Bioelectrochemistry 2015, 102, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hongo, M. , Iwahara, M. , Electrochemical studies on fermentation: Application of electro‐energizing method to l‐glutamic acid fermentation. Agric Biol Chem (Tokyo) 1979, 43, 2075–2081. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou, M. J. C. , Freguia, S. , Rabaey, K. , Carbon and electron fluxes during the electricity driven 1,3‐propanediol biosynthesis from glycerol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 11199–11205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Emde, R. , Schink, B. , Enhanced propionate formation by Propionibacterium Freudenreichii in a 3‐electrode amperometric culture system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990, 56, 2771–2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gimkiewicz, C. , Harnisch, F. , Waste water derived electroactive microbial biofilms: Growth, maintenance, and basic characterization. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 28, (e50800). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fonseca, B. M. , Saraiva, I. H. , Paquete, C. M. , Soares, C. M. , The tetraheme cytochrome from Shewanella oneidensis MR‐1 shows thermodynamic bias for functional specificity of the hemes. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 14, 375–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schutz, B. , Seidel, J. , Sturm, G. , Einsle, O. et al., Investigation of the electron transport chain to and the catalytic activity of the diheme cytochrome c peroxidase CcpA of Shewanella oneidensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 6172–6180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miller, J. C. , Miller, J. N. , Basic statistical‐methods for analytical‐chemistry .1. Statistics of repeated measurements—A review. Analyst 1988, 113, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosenbaum, M. , Cotta, M. A. , Angenent, L. T. , Aerated Shewanella oneidensis in continuously fed bioelectrochemical systems for power and hydrogen production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 105, 880–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting information