Abstract

Bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) are intracellular proteinaceous organelles devoid of a lipid membrane that encapsulates enzymes of metabolic pathways. Salmonella enterica synthesizes propanediol‐utilization BMCs containing enzymes involved in the degradation of 1,2‐propanediol. BMCs can be designed to enclose heterologous proteins, paving the way to engineered catalytic microreactors. Here, we investigate broader applicability of this design principle by directing three different enzymes to the BMC. We demonstrate that β‐galactosidase, esterase Est5, and cofactor‐dependent glycerol dehydrogenase can be directed to the BMC and copurified with the microcompartment shell in a catalytically active form. We show that the BMC shell protects enzymes from pH‐dependent but not from temperature stress. Moreover, we provide evidence that the heterologously expressed BMCs act as a moderately selective diffusion barrier for lipophilic small molecules.

Keywords: Microcompartment, Nano‐bioreactor, Propanediol, Scaffolding, Synthetic biology

Abbreviations

- βGal

beta‐galactosidase

- BMC

bacterial microcompartment

- EP

encapsulation peptide

- MUG

4‐methylumbelliferyl β‐D‐galactopyranoside

- oNPG

o‐Nitrophenyl‐β‐galactoside

- PDO

1,2‐propanediol

- Pdu

propanediol utilization

1. Introduction

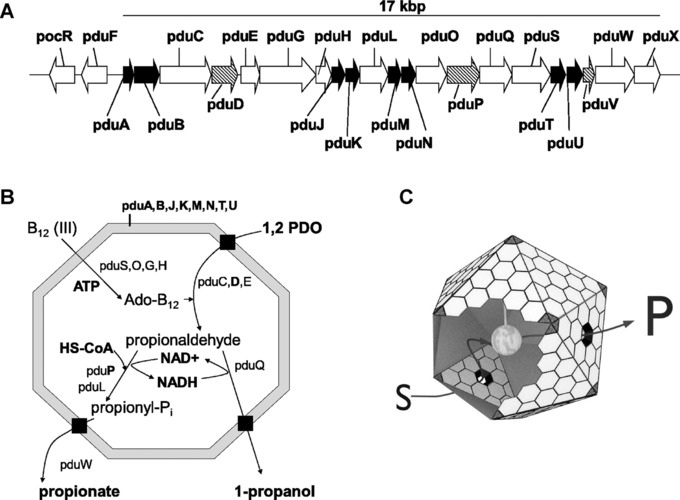

The archetype of a prokaryotic cell lacks lipid‐membrane enclosed subcellular organelles with few exceptions like magnetosomes or annamoxosomes 1, 2. Proteinaceous organelles lacking lipids, however, are widespread in prokaryotes where they often serve metabolic functions (metabolosomes) 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. The prototype of this kind of subcellular biocatalytic entities is the carboxysome of cyanobacteria. The lumen of carboxysomes is filled with RuBisCo (ribulose‐1,5‐bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) and carbonic anhydrase acting synergistically to sequester CO2. Bacterial metabolosomes, also termed bacterial microcompartments (BMC) are thought to protect cells from toxic by‐products and enhance overall turnover rates 8. In our study, we heterologously express the BMCs that Salmonella enterica employs to degrade 1,2‐propanediol (PDO). PDO is produced during microbial breakdown of plant wall sugars (rhamnose, fucose), or lactic acid, e.g. by Lactobacillus species 9. S. enterica synthesises microcompartments when PDO is degraded to sustain growth (Fig. 1). The multicistronic operon involved encodes proteins for the degradation of PDO as well as the proteins constituting the BMC shell. Propionaldehyde is an intermediate of the pathway, and BMCs likely serve to prevent cell damage or loss by sequestering the reactive and volatile aldehyde 3.

Figure 1.

The propanediol utilization (Pdu) microcompartment organelle of bacteria. (A) The pdu‐operon of Salmonella enterica encodes 21 proteins. Gene expression is controlled by the regulatory protein PocR. Eight proteins (black arrows) are sufficient to reconstitute the shell in heterologous hosts (e.g. E. coli). PduD and PduP are involved in degradation of 1,2‐propanediol (PDO). Their N‐termini encode individual peptides that govern protein encapsulation into BMCs 3. (B) Model of PDO degradation in Pdu‐microcompartments (Pdu‐BMC) of Salmonella enterica; black box indicates transport of external substrate across the proteinaceous shell. (C) Ideal model of a protein (gray ball in the center) attached to the inner surface of the bacterial Pdu‐BMC. PduA and PduB assemble into hexameric‐building blocks of the proteinaceous shell. Pentamers (shown in black) presumably encoded by pduN form the vertices of the overall polyhedral 3D‐structure, while the assembled PduB‐subunits form central pores that allow uptake of substrates (S) and efflux of products (P).

Only recently, the mechanism that directs propanediol‐utilization (Pdu) proteins to the lumen of the BMCs was uncovered. The N‐termini of enzymes of the PDO‐degradative pathway (e.g. PduP; Fig. 1) were shown to encode short polypeptides (encapsulation peptides; EP) absent in homologous proteins of non‐BMC‐encoding organisms. Fusing those peptides to GFP led to its association with BMCs 10, 11. The EP of the PduP‐enzyme was shown to interact with the PduA‐subunit of the shell by coiled‐coil interactions of two α‐helices in S. enterica, whereas the PduK‐subunit is the major recognition epitope in BMCs of Citrobacter freundii 12, 13. The mechanism of targeting proteins to the BMC is presently not fully understood but occurs most likely during shell assembly 8, 14, 15. The identification of native EPs and the successful design of nonnatural EPs that direct proteins to the lumen opened the door to rationally reprogram BMCs to provide tailor‐made microreactors for a wide range of applications in synthetic biology, applied biotechnology, and nanotechnology 13, 16, 17.

To date, examples that demonstrate functional association of heterologous enzymes not involved in 1,2‐propanediol or ethanolamine metabolism to the PDU‐BMC are rather limited. One such example was the successful construction of an ethanol‐nanoreactor composed of pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenase from Zymomonas mobilis 13. A key issue probably discouraging more such endeavors is whether the proteinaceous shell acts as a selective barrier restricting substrate access to the lumen 18, 19. Crystal structures of PduA and PduB hexamers suggest substrate selectivity of the pores for, e.g. PDO or glycerol 20, 21. Indirect evidence is provided that the PduA pores of the BMC shell might interact in a selective manner with substrates 22; however, unequivocal direct evidence for absolute transport‐selectivity is a challenging task and currently pending as integrity of engineered BMCs needs to be demonstrated with ultra‐high resolution structural analyses 13. Selective transport of small molecules is important only if BMCs should act as tight intracellular metabolic insulators in the prokaryotic cell. This would enable orthogonal metabolism in engineered living cells 17, 23. A more relaxed transport specificity, however, would still allow for spatiotemporal orthogonality by improving metabolite fluxes due to scaffolding effects 24, 25, 26, which is an important goal in many metabolic engineering concepts. Moreover, protection of enzymes from harsh environmental conditions is a key issue in biocatalysis employing isolated enzymes or even enzyme cascades 27, 28 and BMCs might provide a protective shelter for otherwise susceptible proteins 29.

Here, we demonstrate that enzymes completely unrelated to the native metabolic function of the Pdu BMC can be targeted to a heterologously expressed BMC shell and are putatively incorparated. We demonstrate that engineered enzymes, i.e. esterase Est5 isolated from soil metagenome that cleaves alkylesters, β‐galactosidase hydrolyzing lactose and artificial substrates, and NADH‐dependent glycerol dehydrogenase (GldA) from E. coli, associate with the BMC shell while keeping their enzymatic activity. Moreover, we demonstrate that BMCs offer protection against external pH stress and provide some evidence that BMCs restrict access of lipophilic small molecules to BMC‐associated or incorporated enzyme payloads.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plasmids and cloning

Coding sequences for the BMC shell proteins PduA, ‐B, ‐B’, ‐J, ‐K, ‐M, ‐N, ‐T, and –U were amplified from genomic DNA of Salmonella enterica DSM17058 and cloned into single copy vector pCC1 (BRAIN lab‐collection) by USER fusion 30. Informations on primers and plasmids used in this study are given in supplementary information S8. Expression of the Pdu BMC shell genes is under control of the IPTG‐inducible pTrc promoter; however, LacI is not encoded on pCC1. The corresponding plasmid was termed pCC1‐MQ4.

Midcopy plasmid pBMC‐P (BRAIN lab‐collection) was used to express and target the enzymes to the BMC lumen. Expression of the proteins is under control of the ParaBAD/AraC regulatory system. The plasmid encodes the first 19 AA of the PduP protein followed by a N´‐GGGGS‐C´‐linker peptide (G4S) (Supporting Information S8). The coding sequences of the proteins of interest were fused to the G4S‐linker, and a 6x‐His epitope was added to the C‐terminus of each protein. The genes of the enzymes were amplified from genomic DNA of E. coli K12 W3110 (βGal and GldA), or from plasmid pEst5His_4165 (encoding esterase Est5; BRAIN lab collection).

2.2. Bacterial strains and growth conditions

All expression experiments were conducted using E. coli strain BW25113 31. The cells were aerobically cultured in rich medium (Luria Bertani, LB) at 37°C. Salmonella enterica DSM 17058 was aerobically cultivated in LB medium at 37°C in presence of 4% v/v 1,2‐propanediol to induce synthesis of BMCs. Routinely, cultivation was done overnight (12–16 h).

2.3. Heterologous BMC expression and purification

LB‐medium (50 mL) supplemented with antibiotics was inoculated with an overnight culture to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 and incubated at 37°C and shaken at 250 rpm. At an OD600 of 1.0 expression of enzymes and/or of BMCs was induced simultaneously by adding 0.002% w/v L(+)‐arabinose and/or 400 μM IPTG (isopropyl‐β‐D‐thiogalactopyranoside), respectively. After 5 h of incubation at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm the cells were harvested at 4000 × g for 10 min. BMC purification was conducted as described elsewhere 32. One deviation from the procedure was the usage of BugBuster HT (Merck KGaA, Germany) as the cell‐lysis/protein‐extraction reagent. Cell lysis was done as recommended by the manufacturer.

Purified BMCs (cleared pellet; Supporting Information Fig. S1) were incubated with 60 μL magnetic nickel bead suspension (PureProteome, Merck KGaA, Germany) for 30 min at room temperature, gently rotating. The BMC‐containing supernatant was removed and used for in vitro enzyme assays. The nickel beads‐bound proteins were eluted for analysis by resuspending and incubating the beads in 100 μL elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Eluted proteins were analyzed by SDS‐PAGE, western blot, and in vitro enzyme assays.

2.4. SDS‐PAGE, western blot, and image analysis

Protein concentrations were determined using a Micro BCA Protein Assay (Fisher Scientific GmbH, Germany) with BSA as standard. Twenty micrograms total protein were loaded per well of a 12% SDS‐gel. For western blot analyses, proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes, blocked in PBS supplemented with 5% w/v milk powder and incubated with the primary anti‐tetra‐His antibody overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies were purchased from QIAGEN (Cat. no. 34670) and used in 1:5000 dilutions in PBS containing 2% w/v milk powder. After washing the membranes three times in PBST (PBS supplemented with 0.05% v/v Tween‐20), they were incubated in horseradish peroxidise‐coupled secondary anti‐mouse antibody (GE Healthcare, Cat. no. NA931; 1:15000 in PBS containing 2% w/v milk powder). After three washing steps, chemiluminescence was detected by a horseradish peroxidase assay (Immobilon western, Millipore). The Fiji image processing package (http://fiji.sc/Fiji) was used to make relative quantification of protein bands within the same SDS‐gel or western blot.

2.5. Enzyme assays

The activity of β‐galactosidase (βGal) was determined by a spectrophotometric assay. A 3 μL sample was mixed with 47 μL potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.0). Fifty microliters substrate solution (3 mM o‐nitrophenyl‐β‐galactoside, oNPG; 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0) was added and the formation of 2‐nitrophenol (2‐NP) was monitored at 412 nm. Buffer B (50 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM KCl, 12.5 mM MgCl2, pH 8.0; 32) instead of 3 μL sample was used as blank (negative control) for resuspended BMCs, and nickel bead elution buffer was used as blank for nickel beads eluates. A 2‐NP dilution series in potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 8.0) from 19.5 μM up to 10 mM was used as standard.

4‐Methylumbelliferyl β‐D‐galactopyranoside (MUG) hydrolyzing activities of βGal were measured by diluting 3 μL sample in 47 μL PM buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM MgSO4; pH 7.0) and adding 50 μL substrate solution (1 μM MUG in PM buffer). Fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 370 nm and emission wavelength of 460 nm.

Lactose cleaving β‐galactosidase activities were determined by a two‐step enzymatic assay. First, lactose is hydrolyzed by βGal producing galactose and glucose. Next, galactose is oxidized by the NAD‐dependent galactose dehydrogenase and formation of NADH is monitored. For lactose hydrolyzation, 3 μL of the enzyme containing sample was added to 97 μL β‐lactose buffer (127 mM potassium phosphate, 216 mM β‐lactose, pH 7.0). The reactions were incubated at 30°C for 1 h. After inactivating the enzymes at 99°C for 10 min the amount of produced galactose was measured by mixing 180 μL galactose buffer (4.4 μg/mL BSA, 2.1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM NAD, 0.11 U/mL galactose‐dehydrogenase/‐mutarotase (E‐GALMUT, Megazyme Int., Ireland), 110 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.5) with 20 μL of the lactose‐cleavage reaction. Absorbance was measured at 340 nm after 1 h incubation. Completely hydrolyzed β‐lactose solutions generated from a β‐lactose dilution series ranging from 0.125 to 4 mM was used as standard for quantification.

Esterase activity was determined using 4‐nitrophenyl butyrate (pNP‐butyrate) as substrate. Twenty microliters of enzyme solution was added to 160 μL Tris/HCl buffer (10 mM, pH 8.0). After the addition of 20 μL substrate solution (10 mM pNP‐butyrate in DMSO) the absorbance was recorded at 405 nm.

Glycerol dehydrogenase activities were monitored in buffer 18 (300 mM potassium, 50 mM phosphate, 245 mM glutamate, 20 mM sodium, 2 mM magnesium, 0.5 mM calcium, pH 7.5). Ten millimolar NADH and 10 mM acetol or methylglyoxal, respectively, were added and the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm was monitored.

Experiments to determine the effect of pH and temperature on free or BMC‐associated βGal were done with protein solutions obtained from the same sample after the 20 000 × g centrifugation step (supernatant; step 3, Supporting Information Fig. S1) and after purification of the BMCs with Ni‐beads (step 5, Supporting Information Fig. S1). Supernatant samples were further purified using Ni‐beads and ultrafiltration to deplete contaminating proteins and to enrich βGal roughly threefold. For the experiments testing different pH, 30 μL of each protein solution (free βGal or BMC‐associated βGal) were mixed gently with 120 μL of a 50 mM Na‐citrate buffer solution adjusted to the respective pH (3–7), and incubated for 60 min at 4°C. Next, 1350 μL of potassium‐phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.0) was added to ensure identical pH of the different protein solutions. Fifty microliters of this solution was mixed with 50 μL of an oNPG solution (3 mM in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8) and the absorbance at 412 nm was recorded over 2 h at 30°C to calculate the βGal activity. For experiments testing the effect of different temperatures on βGal activity, 20 μL of said protein solution was incubated in a thermocycler at the given temperature for 15 min. Three microliters of the heat‐treated protein solution was then used for the standard oNPG assay as described above.

2.6. Electron microscopy

EM‐preparation started with High‐Pressure‐Freezing (HPM100, Leica, Germany) of bacterial cells pelleted in their respective medium plus 20% BSA, followed by freeze substitution (AFS2, Leica, Germany) in acetone including 0.5% OsO4/0.2% uranyl acetate/0.5% glutaraldehyde/0.5% water, running a temperature‐slope from –90° to –25°C during two days, washed in acetone at –20°C and embedding in epoxide (glycid‐ether/MNA/DDSA; Serva Electrophoresis GmbH, Germany) after equilibration to room temperature. Ultrathin sections of nominal thickness 60 nm were stained with uranyl and lead and investigated with an EM910 (Carl‐Zeiss, Germany). Micrographs were registered on image‐plates at 16 000 × primary magnification and scanned at 30 μm resolution (Ditabis, Germany).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Expression of the microcompartment shell of Salmonella enterica in Escherichia coli

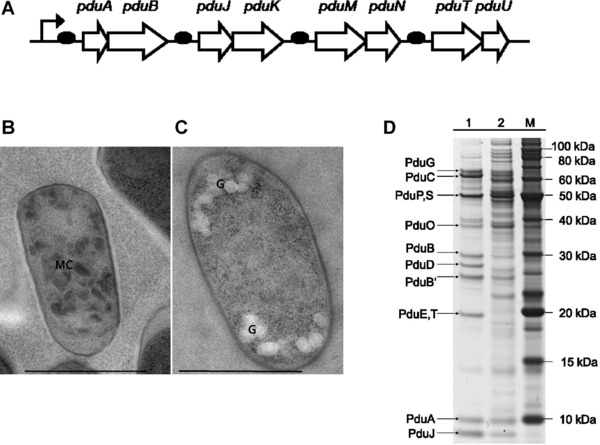

A functional minimal‐shell of the Pdu‐BMC was generated by expressing the genes pduA, ‐B, ‐J, ‐K, ‐M, ‐N, ‐T, and ‐U 32, 33. We amplified the corresponding genes from genomic DNA of S. enterica strain LT2 (DSM 17058) and cloned the amplicons as a synthetic operon in the single copy vector pCC1. We generated four PCR products encoding the genes pduAB, pduJK, pduMN, and pduTU and assembled the amplicons in vector pCC1‐MQ4. A synthetic Shine‐Dalgarno sequence (SD) of the pET3a vector precedes the genes pduA, ‐J, ‐M, and ‐T, whereas translation of the genes pduB, ‐K, ‐N, and ‐U is initiated by their authentic SD (Fig. 2). Construction and expression of the empty BMC shell was performed according to the protocol established by Parsons et al., who demonstrated the expression of a functional Pdu shell from Citrobacter freundii in E. coli 33 with the exception that we used the pTrc‐ instead of the T7‐promoter for transcription of the shell genes.

Figure 2.

Heterologous expression of S. enterica Pdu‐BMCs in E. coli. (A) Scheme of operon design for heterologous expression of the Pdu shell proteins under the control of the pTrc promoter. Synthetic Shine‐Dalgarno sequences sites (black ovals) precede the pduA, ‐J, ‐M, and ‐T genes; translation of the remaining genes is initiated by native elements. (B) Transmission electron micrograph of an E. coli BW25113 cell harboring plasmid pCC1‐MQ4 induced with 0.4 mM IPTG to express the minimal shell BMC. The cell is compartmentalized by many irregular dark bodies [MC]. (C) Noninduced cell harboring pCC1‐MQ4 cultivated in presence of 1% glucose (negative control, bright granules [G] represent glyocogen); Bar, 1 μm. (D) Comparison of shell‐protein expression levels in native and heterologous host cells. BMCs were prepared as described elsewhere 32 from S. enterica cultivated in presence of 4% v/v 1,2‐propanediol (lane 1), or from E. coli harboring plasmid pCC1‐MQ4 induced with 0.4 mM ITPG (lane 2).

We analyzed expression of the BMC shell by SDS‐PAGE and electron microscopy. Expression of the BMC encoding genes reduced the growth rate of E. coli by 8–20% compared to the control (pCC1) indicating a metabolic burden due to protein synthesis. Bacterial microcompartments comprise 5000–20 000 proteins 3 and we observed 20–30 BMC‐like microbodies in recombinant BMC expressing cells (Fig. 2). SDS‐PAGE analysis was done to compare the expression of shell proteins of our heterologous system with that of Salmonella cells treated with 1,2‐propanediol to induce the expression of authentic BMCs. The most abundant shell proteins PduA, ‐B, ‐B´ (the PduB‐gene has two alternative translational start sites) and PduJ were readily visible in preparations of BMC expressing cells (Salmonella and E. coli; Fig. 2). We detected four out of the nine (PduB,‐B´ regarded as individual proteins) shell proteins necessary for the minimal shell in the E. coli sample. The expression of PduK, ‐M, ‐N, ‐T, and ‐U could not be demonstrated. However, the missing proteins were not detected in the Salmonella sample, which represents the authentic expression levels, either. PduE and PduT have almost the same molecular weight (19.14 or 19.15 kDa, respectively). Hence, the distinct band of corresponding size clearly visible in the Salmonella sample could not be attributed unequivocally to PduT. A SDS‐PAGE analysis by Parsons et al. working on isolated BMCs from Citrobacter expressed in E. coli, revealed similar results 34. Therefore, we assume that missing protein bands reflect a rather low expression level of the corresponding proteins necessary for correct assembly of the BMC‐shell.

Electron microscopy of recombinant E. coli cells harbouring the empty plasmid pCC1 (negative control) or expressing the shell proteins (pCC1‐MQ4) detected irregular shaped polyhedral mircrobodies exclusively in pCC1‐MQ4 harboring cells (Fig. 2). Irregular polyhedral BMCs different from the ideal icosahedral form have been described for some purified BMCs or carboxysomes are common observations even in native systems 35. Purification of BMCs, e.g. by sucrose‐gradient centrifugation, enriches nearly‐ideal‐icosahedral shaped BMCs and analysis of BMCs in cells revealed irregularly shaped polyhedra also for carboxysomes, ethanolamine‐, and Pdu‐BMCs in their native host 14. Moreover, a recent general model predicts a wide range of polyhedral bodies formed spontaneously in multicomponent shells 36. Therefore, the common notion that only ideally formed BMCs are intact might be misleading.

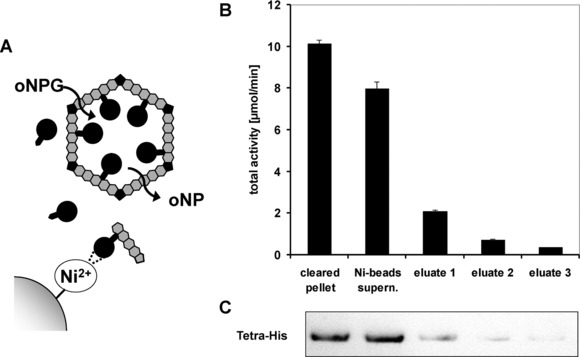

3.2. Affinity purification of BMCs loaded with heterologous enzymes

Coexpression of the target‐enzyme and the BMC shell encoding genes has to be fine‐tuned in order to ensure the absence of unbound target‐enzyme in the preparation of reprogrammed BMCs. We circumvented this challenge by including an affinity‐purification step in our modified BMC‐purification protocol. We basically followed the well‐established method of Sinha et al. 32 and added purification by nickel‐coated magnetic beads to provide essentially pure preparations of recombinant BMCs for our enzymatic in vitro assays. The purification protocol (Supporting Information Fig. S1) was established for the βGal enzyme and was later on successfully applied for the purification of Est5 and GldA. A typical result of the purification protocol is described in the Supporting Information S1.

Affinity purification using Ni‐coated magnetic beads depleted nonencapsulated enzymes efficiently. The three enzymes used in this work were expressed as C‐terminal His‐tag fusions. The use of Ni‐coated magnetic beads enabled the preparation of pure and intact BMCs due to avoidance of any harsh physical treatments (e.g. high pressure or shear forces). The beads bind His‐tagged enzymes unless the enzymes are sheltered by intact BMCs. Accordingly, we used Ni‐bead purification to deplete free (i.e. unbound, nonencapsulated) enzyme, as well as fractions of broken or misfolded BMCs, hereafter collectively termed contamination.

Western blot analysis of proteins eluted from the Ni‐beads demonstrated that three successive incubations with fresh Ni‐beads sufficed to deplete >99% of the contaminations. Enzyme activities of proteins eluted from the beads gave corresponding results (>96% depletion; Fig. 3). Proteins eluted from the Ni‐beads show faint bands corresponding to PduA, ‐B and ‐J along with the enzyme (Supporting Information Fig. S7). This observation demonstrates accessibility of the His‐tag epitope to the Ni‐coated beads when the His‐tagged enzymes associate with ill‐formed BMCs. Hence, our in vitro assays were effectively devoid of contaminating enzyme species contributing no more than 4% of the determined activities. Therefore, we argue that the observed turnover of the different substrates was catalyzed by encapsulated or tightly associated (but sheltered) enzymes that are not exposed to the bulk liquid phase in our in vitro assays.

Figure 3.

Affinity purification depletes nonencapsulated enzyme from the in vitro assay system. BMCs containing β‐galactosidase‐His tagged with the PduP‐encapsulation peptide (P‐βGal; black circles) were purified and subsequently incubated three times with fresh Ni2+‐coated magnetic beads. (A) Upon incubation with Ni‐beads, the supernatant was enriched with intact BMCs that do not interact with the magnetic beads. Beads were separated from the supernatant, washed, and bound proteins were eluted. The eluent contained unbound P‐βGal or P‐βGal associated with ill‐assembled or broken BMCs. (B) Total activity of β‐galactosidase of the supernatant or the eluent was determined by the oNPG‐assay. (C) P‐βGal content of each eluent sample was determined by western blot analysis using an anti‐tetra‐His antibody.

3.3. Heterologous enzymes differentially associate with the BMC shell

S. enterica degrades 1,2‐propanediol via a multistep pathway including CoA‐dependent propionaldehyde dehydrogenase (PduP; Fig. 1). Individual N‐terminal peptides direct proteins to the lumen of BMCs, most likely during assembly and folding of the BMC‐shell 15, 37. For S. enterica, the interaction between shell proteins and the EP was uncovered for the PduA‐PduP pair on the molecular level 12. The study suggests that the N‐terminus of PduP and C‐terminus of PduA both form helical structures that bind one another via key residues of the helical structures involved. By fusing the first 18 amino acids (AA) of PduD or PduP to the N‐terminus of the GFP‐protein, Bobik and coworkers demonstrated targeting of heterologous proteins to the lumen of the Pdu‐BMC in Salmonella 10, 11. We fused the first 19 AA of PduP to three different enzymes: β‐galactosidase (βGal) and glycerol dehydrogenase GldA of E. coli, and Est5, an esterase isolated from a soil metagenome sample. A 6xHis‐tag was also fused to the C‐terminus of each enzyme for detection and purification purposes. The corresponding fusion proteins were individually expressed from plasmid pBMC‐P (midcopy number) under control of the ParaBAD/AraC regulatory system that was induced by the addition of 0.002% w/v L‐arabinose. Corresponding constructs lacking the targeting‐ and linker sequence served as control.

We show that the three individual enzymes (βGal, Est5, GldA) were successfully targeted to the BMCs as they copurified with major shell proteins (Fig. 6). Thus, PduP peptide‐mediated targeting of proteins allows for modular design in reprogramming BMCs with heterologous proteins, which was demonstrated only for pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenase so far 13. Moreover, accumulation was strongly dependent on the presence of the PduP‐targeting peptide, indicating that unspecific incorporation of untagged proteins during BMC‐assembly appears to be negligible (Fig. 4). The extent of protein targeting to the BMCs varied. We observed a >63‐fold accumulation for Est5, whereas the accumulation of βGal and GldA was lower (roughly 25‐fold) when accumulation levels were normalized to the prominent band of the PduB‐shell protein of each sample (Fig. 6). Together with previous reports by other groups, peptide‐mediated targeting seems to be suitable to rationally reprogram the Pdu‐BMC with various heterologous proteins. Four native EPs (PduD, PduL, PduP, PduV) are currently available that had been engineered to compete with the native EPs, thus allowing to control the ratio between the heterologous proteins to be encapsulated 16, 38. However, our observations indicate that the nature of the cargo‐protein might influence targeting efficiency and encapsulation in a so far elusive manner, too, thereby complicating the rational design. Interestingly, βGal, which is active in the homotetrameric form, retained activity although every single monomer was fused to the PduP‐EP. Here, a surplus in expression of βGal over the PduA‐level might enable tetramer‐formation of βGal during BMC formation. Accordingly, even protein complexes might be incorporated into BMCs, although only one of the subunits has the respective EP. Notably, the PduCDE diol dehydratase of the native Pdu‐BMC of Salmonella is supposed to be a dimer of heterotrimers (αβψ )2, that is targeted via the PduD‐EP to the lumen of the BMC 3.

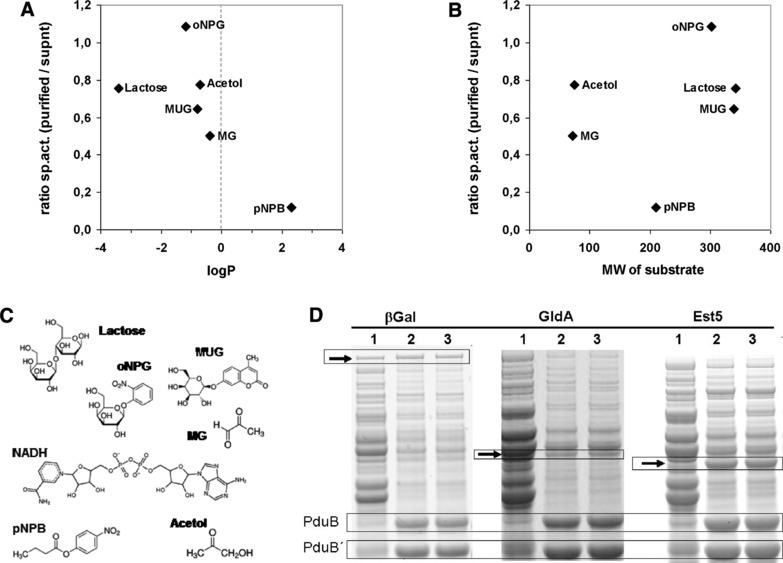

Figure 6.

Specific activities of enzymes associated to BMCs correlates with the partition coefficient logP of substrates. The ratio of the specific activities of enzymes associated with BMCs and of the enzymes not associated with BMCs of the same expression experiment was plotted against the logP (A) or the molecular weight (B) of the substrate compounds. LogP describes the distribution of a given compound in an octanol‐water biphasic solution system. Lipophilic compounds have positive logP values and vice versa. In the graphs, a ratio of 1 indicates unrestricted access of substrates to the BMC‐associated enzyme. (C) Molecular structure of the substrate compounds used in this study; abbreviations, see table S6. (D) SDS‐PAGE analyses of the protein samples used for this analysis demonstrate similar amounts of βGal in the soluble and the BMC‐containing fraction, whereas esterase Est5 is strongly enriched in the BMC‐fraction. Arrows indicate relevant protein bands; PduB, PduB´, major shell proteins of the BMC used for comparing protein amounts. Lane 1, supernatant after centrifugation at 20 000 × g, BMCs are largely depleted; lane 2, cleared pellet, i.e. resuspended pellet after the 20 000 × g centrifugation step; lane 3, purified BMCs after affinity purification using magnetic Ni‐beads to deplete unbound enzymes. Protein samples corresponding to lanes 1 and 3 were used for determining the ratio of the specific activities plotted in graph (A) and (B).

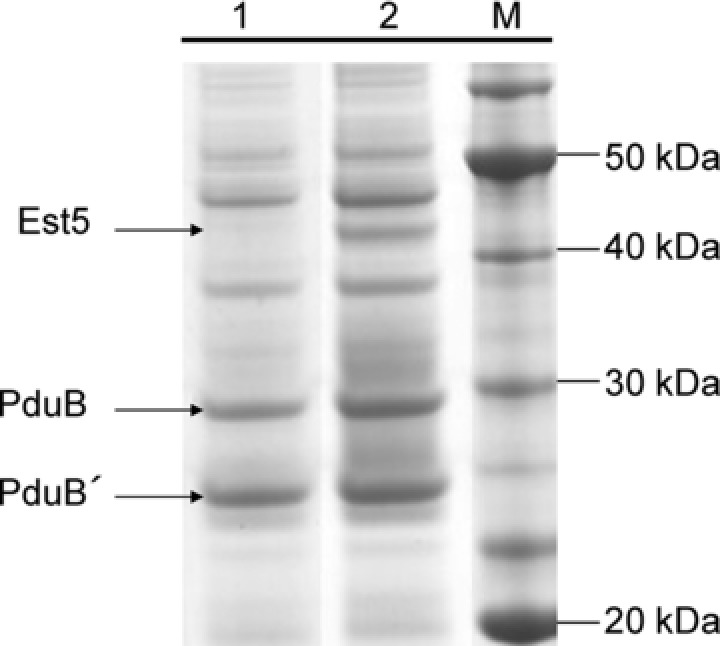

Figure 4.

Association of proteins to BMCs is strongly dependent on the targeting peptide. Esterase Est5 (43 kDa) was cloned with or without the PduP‐encapsulation peptide and coexpressed in E. coli BW25113 together with the BMC‐genes encoded by pCC1‐MQ4. Lane 1, Est5 without the encapsulation peptide coexpressed with BMC‐genes; lane 2, Est5 with the PduP‐encapsulation peptide fused to the N‐terminus and coexpressed with BMC‐genes.

3.4. Encapsulation peptide impacts enzyme activity

In order to target the three enzymes βGal, Est5, and GldA to the BMCs, we fused the first 19 AA of PduP via the flexible glycine‐serine rich peptide linker (N´‐GGGGS‐C´; G4S; Supporting Information S8) to the N‐terminus of the different enzymes. Fusion of the EP to the target protein via a flexible peptide linker should minimize potentially adverse effects on enzyme activity 39.

We examined the influence of the PduP‐EP fused to the G4S‐peptide on the esterase or the β‐galactosidase (βGal) activity in the absence of the BMC‐shell proteins in crude extracts. We observed opposite effects for the two enzymes tested. While the specific activity of Est5 toward the pNPB substrate decreased by 42%, βGal activity (oNPG substrate) increased by 290% (Supporting Information Table S4). Corresponding SDS‐PAGE analyses revealed improved expression for each of the peptide‐tagged enzyme variants by a factor of 2. Therefore, we conclude that the individual influence of the targeting peptide is rather context‐specific comprising all the different aspects of protein expression, including stability of mRNA transcripts, translation‐initiation mechanisms, or the overall protein structure. Consequently, the effect of the targeting peptide on the catalytic performance of retargeted enzymes cannot be predicted a priori and has to be evaluated empirically. Likewise, Warren and coworkers observed lowered specific activities for three out of four tagged enzymes of a synthetic 1,2‐propanediol production pathway when the EPs of PduD or PduP were fused to the enzymes. Notably, the EPs were fused without any flexible linker to the enzymes 26.

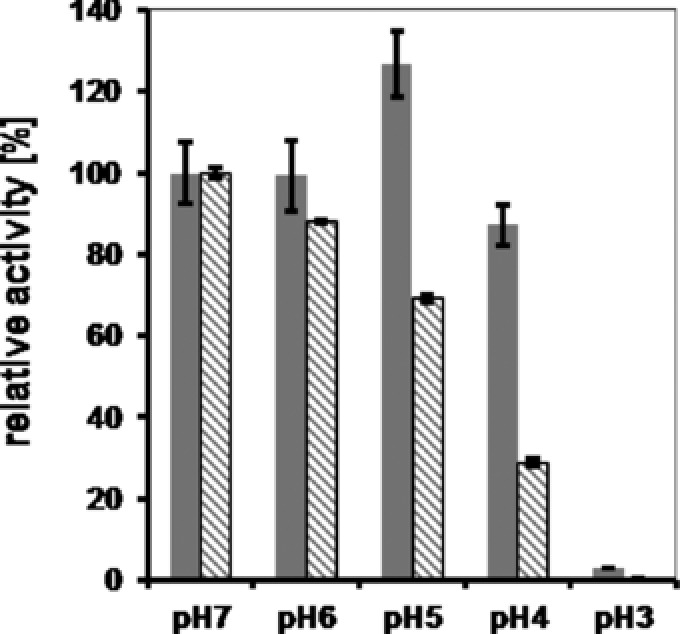

3.5. The BMC‐shell proteins protect β‐galactotsidase from pH but not from temperature stress

The major function of BMCs in vivo appears to be protecting cells from toxic intermediates of metabolic pathways or to prevent loss of volatile intermediates either by restricted diffusion or enhanced turnover due to scaffolding effects. For in vitro applications, e.g. in cell‐free environments, BMCs might protect their enzyme payloads from harsh environments. A systematic survey of the shape of purified BMCs under different stress conditions revealed remarkable stability of the shell 29. However, no analyses concerning protection of the encapsulated cargo proteins have been performed. We tested βGal as a blueprint for catalytically active enzymes and tested whether the BMC shell offers protection against pH and temperature stress. Free βGal not associated with the BMC shell was sensitive only toward acid pH, but not toward alkaline pH (Supporting Information Fig. S3). Therefore, our analysis was restricted to pH values between 3 and 7. The βGal activity determined at pH7 was set 100% and we observed almost complete inhibition of the βGal activity at pH3 for the unsheltered enzyme while the BMC‐associated βGal retained 2.9% compared to the activity at pH7. The protective effect of BMCs was most pronounced between pH4 to pH6. At pH4, the unsheltered enzyme retained only 13% of the activity while BMC‐associated βGal retained 87% of the reference activity (Fig. 5). At pH5, the activity was significantly improved for the BMC‐assosicated βGal (126%) whereas the free enzyme showed 30% loss in activity (Supporting Information Fig. S3). Interestingly, Kim et al. observed distortion of the BMC structure and a decrease in size at pH5 and below 29. Improved cooperativity of the βGal monomers due to the decreased BMC size, improved access of the oNPG substrate due to distortion of the shell or other, so far unknown mechanisms, might account for the increased βGal activity. Regardless of the exact mechanism, our results indicate that BMCs offer protection at least from acidic pH stress in cell‐free environments. This was not the case for temperature stress (Supporting Information Fig. S2). We tested the activity of the βGal in the standard assay after a 15 min incubation of the free or BMC‐associated enzyme at temperatures between 35 and 60°C. The activity determined after the incubation step at 4°C served as reference activity and was set as 100%. We observed no significant decrease in activity up to temperatures of 44°C for both, free and BMC‐associated βGal. The βGal activity started to decrease at 50°C. No βGal activity was detected for temperatures above 58°C. Our observations are in line with the results by Kim et al. who observed the onset of BMC‐shell denaturation starting at temperatures of 53°C 29. Association of the enzyme with BMCs thus could not increase the thermostability of the bGal‐activity, an expected result as heat—unlike pH—is a physical stressor.

Figure 5.

Protection of BMC‐associated β‐galactosidase from acidic pH. β‐Glactosidase (βGal) of E. coli W3110 was expressed in E. coli in presence or absence of BMCs. After affinity purification of the free enzyme or the βGal containing BMCs, both protein solutions were incubated for 60 min at 4°C in buffer solutions (Na‐citrate) adjusted to the respective pH. Thereafter, protein solutions were diluted threefold in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH7, and 50 μL were subsequently used in the standard oNPG assay for the determination of the specific activity. Gray bars, βGal associated with BMCs; hatched bars, βGal without BMCs.

3.6. Indications that the BMC‐shell acts as a hydrophobic diffusion barrier

The physiological function of BMCs is still a matter of debate in the current literature 40. One function might be the restriction of free diffusion of highly reactive, volatile, or toxic compounds within the cytosol to prevent damage or loss of carbon from the cell. Correspondingly, ruptured shells of a cyanobacterial carboxysome enabled a roughly threefold improved rate of CO2‐hydration by carbonic anhydrase compared to intact carboxysomes 41. The Pdu‐BMCs of Salmonella have to allow transport of PDO, and crystal‐structures obtained from purified hexamers of the Pdu‐BMC from Lactobacillus sp. show glycerol molecules trapped in the central pore of the BMC‐subunits 21. Highly selective transport, however, will limit broader use of BMCs in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology applications as the pores needed to be individually engineered to allow transport of a given substrate. Likewise, Bobik and coworkers recently described that engineering the PduA‐subunit of the Pdu‐BMC affects growth rates of Salmonella when PDO or propionaldehyde serves as carbon source, probably due to altered transport specificities of the PduA‐pore 22. The construction of a recombinant ethanol nanoreactor based on Pdu‐BMCs converting pyruvate to ethanol, on the other hand, challenges the idea of BMCs acting as tight metabolic insulators, although integrity of the reprogrammed BMCs was not investigated 13.

With the availability of three different heterologous enzymes that could be fused to the PduP‐EP while keeping their activity, and with the availability of essentially pure Pdu‐BMC preparations from E. coli, we decided to further investigate evidences for transport‐selectivity or promiscuity of BMCs with the help of in vitro enzyme assays. Our basic concept followed the idea that the specific activity of enzymes encapsulated in BMCs should be lower compared to nonencapsulated enzymes if transport across the BMC‐shell is the rate‐limiting step of the substrate conversion. In one extreme scenario, no other than the native substrate (i.e. 1,2‐propanediol) could cross the proteinaceous shell; likewise, a completely unselective shell will give access to the BMC‐associated enzymes to any kind of molecule independent of its physical properties. Accordingly, the observation of differential enzyme kinetics for the conversion of the different, nonnative substrates indicates both, integrity of the BMC‐shell and relaxed transport selectivity.

Esterase Est5, β‐galactosidase, and glycerol‐dehydrogenase were individually coexpressed with BMCs and purified. After removal of cell debris, the second centrifugation step (step 3, Supporting Information Fig. S1) separated unbound enzymes (supernatant) from BMC‐bound enzymes. The BMCs were further purified from weakly associated enzymes via affinity purification as detailed above. Individual in vitro activity assays were performed for the supernatant or BMC‐preparations, respectively, and the specific activity was calculated (Supporting Information Table S5). Next, we calculated the ratio between the specific activity of enzymes bound to the BMC and those of the supernatant. A ratio of 1 indicates unrestricted interaction of substrate and enzyme using reprogrammed BMCs for enzymatic catalysis. A ratio significantly lower than 1 indicates restricted interactions, most likely due to rate‐limiting transport processes across the proteinaceous shell. We observed ratios between 1.08 for βGal/oNPG and 0.12 for Est5/pNPB combinations. Next, we plotted the ratios against either the molecular weight or the logP partition coefficient of the compounds (Fig. 6; Supporting Information Table S5). We observed no correlation for the molecular weight of the substrate molecules. However, a trend was observed concerning hydrophilicity of the substrate molecules (hydrophobic substrates have logP values >0). Compounds with negative logP values (i.e. hydrophilic compounds) are clearly separated from the hydrophobic compound tested (p‐nitrophenylbutyrate, pNPB; logP = 2.3). The supposed native substrates and products of the Pdu‐BMC show negative or slightly positive logP values. Interestingly, methylglyoxal, a highly reactive aldehyde, shows the lowest ratio (0.5) within the hydrophilic group of compounds in our analysis (Supporting Information Table S6). We conclude that hydrophilic compounds can diffuse more easily to or across the BMC shell than hydrophobic compounds. This conclusion is in line with recent studies of engineered PduA‐variants in Salmonella. The mutant PduA‐S40A pore is less polar than the wild‐type pore and allowed for enhanced secretion of the otherwise retarded propionaldehyde (logP = 0.6) 22. We cannot prove absolute integrity of the BMCs we used for our in vitro assays and ill‐formed BMCs might give access to nonnatural substrates. However, differential ratios for the specific activities indicate intact BMCs. Our results demonstrate, that even heterologously expressed BMCs can be used by biotechnologists to gain control over otherwise unrestricted diffusion of small hydrophobic molecules in noncompartmentalized environments.

4. Concluding remarks

Bacterial microcompartments have been investigated for more than 20 years but only gained increased attention recently when the mechanism of targeting heterologous payloads to these proteinaceous cargos had been uncovered. With these insights, biotechnologists, especially synthetic biologists, start to envision diverse applications with rationally designed BMCs acting as nanobioreactors for in vitro or in vivo applications in biotechnology or even in medicine, where they might be used to precisely deliver therapeutics to the target cells 17, 42. The ability to express BMCs in heterologous hosts offers plug‐and‐play strategies for engineering the platform organisms used in synthetic biology. Alternatively, BMCs encoded by the native hosts might be easily engineered using genome‐editing technologies like the CRISPR‐Cas system. Despite all these possibilities, the number of reports on reprogrammed BMCs is rather scarce yet, and mainly relies on GFP as a reporter system that does not have catalytic activity. Our results expand the number of proof‐of‐concept cases, demonstrating that quite different enzymes can be successfully targeted to the BMC while keeping their activity. Notably, we could show that multimeric or cofactor dependent enzymes retain activity. Moreover, we demonstrate that BMCs might be a suitable means to protect sensitive enzymes from harsh environments. The notion that transport across the proteinaceous shell is rather specific might have discouraged synthetic biologists to harness BMCs to a greater extent. However, absolute specificity of the transport of small molecules across the shell has not been unequivocally demonstrated so far. As long as insulation of metabolic reactions or pathways—e.g. for establishing orthogonal metabolism in the noncompartmentalized prokaryotic cell 23—is not required, integrity of heterologously expressed BMCs or successful encapsulation of the payloads might not be an issue. We and others demonstrate that harnessing the BMC‐technology offers a novel and advantageous design principle for synthetic biology applications 13, 26.

Practical application

Bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) are exclusively composed of proteins and lack any lipid membrane. Therefore, they can be rationally designed and expressed in heterologous hosts. We show that hydrolases and oxidoreductases can be targeted to the BMC while keeping their activity. Moreover, BMCs offer protection against acidic pH stress and restrict diffusion of lipophilic compounds. Rationally designed BMCs might therefore find broad applications in biocatalysis. Here, they can provide a scaffolding platform to build up enzyme‐cascades that can be easily designed and produced in a scalable manner in heterologous hosts. Rationally designed BMCs might be also used to optimize intracellular metabolite fluxes in living cells, although fine‐tuning of the expression levels of the BMC‐shell and its corresponding cargo proteins is a challenging task. Recombinant BMCs will be especially useful in complex biosynthetic pathways that produce toxic or volatile intermediates that otherwise might harm the living cell.

J.M. is an employee of the BRAIN AG.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information S1

Acknowledgments

We thank T.J. Goedecke for performing the measurements of the activity of βGal at different pH and temperature. We thank Dr. Klaus Liebeton (BRAIN AG) for providing esterase Est5 and fruitful discussions.

5 References

- 1. Lefevre, C. T. , Wu, L. F. , Evolution of the bacterial organelle responsible for magnetotaxis. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shively, J. , Cannon, G. , Heinhorst, S. , Fuerst, J. et al., Intracellular structures of prokaryotes: Inclusions, compartments and assemblages, in: Schaechter M. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Microbiology, Academic Press, Oxford: 2009, pp. 404–424. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chowdhury, C. , Sinha, S. , Chun, S. , Yeates, T. O. et al., Diverse bacterial microcompartment organelles. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2014, 78, 438–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lassila, J. K. , Bernstein, S. L. , Kinney, J. N. , Axen, S. D. et al., Assembly of robust bacterial microcompartment shells using building blocks from an organelle of unknown function. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 2217–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Erbilgin, O. , McDonald, K. L. , Kerfeld, C. A. , Characterization of a planctomycetal organelle: A novel bacterial microcompartment for the aerobic degradation of plant saccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2193–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schuchmann, K. , Schmidt, S. , Martinez Lopez, A. , Kaberline, C. et al., Nonacetogenic growth of the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii on 1,2‐propanediol. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 382–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Held, M. , Kolb, A. , Perdue, S. , Hsu, S. Y. et al., Engineering formation of multiple recombinant Eut protein nanocompartments in E. coli . Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cameron, J. C. , Wilson, S. C. , Bernstein, S. L. , Kerfeld, C. A. , Biogenesis of a bacterial organelle: The carboxysome assembly pathway. Cell 2013, 155, 1131–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oude Elferink, S. J. , Krooneman, J. , Gottschal, J. C. , Spoelstra, S. F. et al., Anaerobic conversion of lactic acid to acetic acid and 1, 2‐propanediol by Lactobacillus buchneri . Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fan, C. , Bobik, T. A. , The N‐terminal region of the medium subunit (PduD) packages adenosylcobalamin‐dependent diol dehydratase (PduCDE) into the Pdu microcompartment. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 5623–5628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fan, C. , Cheng, S. , Liu, Y. , Escobar, C. M. et al., Short N‐terminal sequences package proteins into bacterial microcompartments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7509–7514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fan, C. , Cheng, S. , Sinha, S. , Bobik, T. A. , Interactions between the termini of lumen enzymes and shell proteins mediate enzyme encapsulation into bacterial microcompartments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14995–15000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lawrence, A. D. , Frank, S. , Newnham, S. , Lee, M. J. et al., Solution structure of a bacterial microcompartment targeting peptide and its application in the construction of an ethanol bioreactor. ACS Synth. Biol. 2014, 3, 454–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tocheva, E. I. , Matson, E. G. , Cheng, S. N. , Chen, W. G. et al., Structure and expression of propanediol utilization microcompartments in Acetonema longum . J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 1651–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sutter, M. , Faulkner, M. , Aussignargues, C. , Paasch, B. C. et al., Visualization of bacterial microcompartment facet assembly using high‐speed atomic force microscopy. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 1590–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jakobson, C. M. , Kim, E. Y. , Slininger, M. F. , Chien, A. et al., Localization of proteins to the 1,2‐propanediol utilization microcompartment by non‐native signal sequences is mediated by a common hydrophobic motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 24519–24533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chessher, A. , Breitling, R. , Takano, E. , Bacterial microcompartments: Biomaterials for synthetic biology‐based compartmentalization strategies. ACS Biomat. Sci. Eng. 2015, 1, 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cai, F. , Sutter, M. , Bernstein, S. L. , Kinney, J. N. et al., Engineering bacterial microcompartment shells: Chimeric shell proteins and chimeric carboxysome shells. ACS Synth. Biol. 2015, 4, 444–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sinha, S. , Cheng, S. , Sung, Y. W. , McNamara, D. E. et al., Alanine scanning mutagenesis identifies an asparagine‐arginine‐lysine triad essential to assembly of the shell of the Pdu microcompartment. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 2328–2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crowley, C. S. , Cascio, D. , Sawaya, M. R. , Kopstein, J. S. et al., Structural insight into the mechanisms of transport across the Salmonella enterica Pdu microcompartment shell. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 37838–37846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pang, A. , Liang, M. , Prentice, M. B. , Pickersgill, R. W. , Substrate channels revealed in the trimeric Lactobacillus reuteri bacterial microcompartment shell protein PduB. Acta Crystallogr. 2012, 68, 1642–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chowdhury, C. , Chun, S. , Pang, A. , Sawaya, M. R. et al., Selective molecular transport through the protein shell of a bacterial microcompartment organelle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2990–2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mampel, J. , Buescher, J. M. , Meurer, G. , Eck, J. , Coping with complexity in metabolic engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee, H. , DeLoache, W. C. , Dueber, J. E. , Spatial organization of enzymes for metabolic engineering. Metab. Eng. 2012, 14, 242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Castellana, M. , Wilson, M. Z. , Xu, Y. , Joshi, P. et al., Enzyme clustering accelerates processing of intermediates through metabolic channeling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 1011–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee, M. J. , Brown, I. R. , Juodeikis, R. , Frank, S. et al., Employing bacterial microcompartment technology to engineer a shell‐free enzyme‐aggregate for enhanced 1,2‐propanediol production in Escherichia coli . Metab. Eng. 2016, 36, 48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Idan, O. , Hess, H. , Engineering enzymatic cascades on nanoscale scaffolds. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 606–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmidt, S. , Scherkus, C. , Muschiol, J. , Menyes, U. et al., An enzyme cascade synthesis of epsilon‐caprolactone and its oligomers. Angewandte Chemie 2015, 54, 2784–2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim, E. Y. , Slininger, M. F. , Tullman‐Ercek, D. , The effects of time, temperature, and pH on the stability of PDU bacterial microcompartments. Protein Sci. 2014, 23, 1434–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Geu‐Flores, F. , Nour‐Eldin, H. H. , Nielsen, M. T. , Halkier, B. A. , USER fusion: A rapid and efficient method for simultaneous fusion and cloning of multiple PCR products. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baba, T. , Ara, T. , Hasegawa, M. , Takai, Y. et al., Construction of Escherichia coli K‐12 in‐frame, single‐gene knockout mutants: The Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006, 2, 2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sinha, S. , Cheng, S. , Fan, C. , Bobik, T. A. , The PduM protein is a structural component of the microcompartments involved in coenzyme B(12)‐dependent 1,2‐propanediol degradation by Salmonella enterica . J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 1912–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parsons, J. B. , Frank, S. , Bhella, D. , Liang, M. et al., Synthesis of empty bacterial microcompartments, directed organelle protein incorporation, and evidence of filament‐associated organelle movement. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Parsons, J. B. , Dinesh, S. D. , Deery, E. , Leech, H. K. et al., Biochemical and structural insights into bacterial organelle form and biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 14366–14375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yeates, T. O. , Thompson, M. C. , Bobik, T. A. The protein shells of bacterial microcompartment organelles. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011, 21, 223–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vernizzi, G. , Sknepnek, R. , Olvera de la Cruz, M. , Platonic and Archimedean geometries in multicomponent elastic membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4292–4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aussignargues, C. , Paasch, B. C. , Gonzalez‐Esquer, R. , Erbilgin, O. et al., Bacterial microcompartment assembly: The key role of encapsulation peptides. Comm. Integr. Biol. 2015, 8, e1039755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu, Y. , Jorda, J. , Yeates, T. O. , Bobik, T. A. , The PduL phosphotransacylase is used to recycle coenzyme a within the Pdu microcompartment. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 2392–2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lu, P. , Feng, M. G. , Bifunctional enhancement of a beta‐glucanase‐xylanase fusion enzyme by optimization of peptide linkers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 79, 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Penrod, J. T. , Roth, J. R. , Conserving a volatile metabolite: A role for carboxysome‐like organelles in Salmonella enterica . J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 2865–2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Heinhorst, S. , Williams, E. B. , Cai, F. , Murin, C. D. et al., Characterization of the carboxysomal carbonic anhydrase CsoSCA from Halothiobacillus neapolitanus . J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 8087–8094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Corchero, J. L. , Cedano, J. , Self‐assembling, protein‐based intracellular bacterial organelles: Emerging vehicles for encapsulating, targeting and delivering therapeutical cargoes. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information S1