Abstract

Background

Influenza vaccination is recommended for asthmatic patients in many countries as observational studies have shown that influenza infection can be associated with asthma exacerbations. However, influenza vaccination has the potential to cause wheezing and adversely affect pulmonary function. While an overview concluded that there was no clear benefit of influenza vaccination in patients with asthma, this conclusion was not based on a systematic search of the literature.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the efficacy and safety of influenza vaccination in children and adults with asthma.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Airways Group trials register and reviewed reference lists of articles. The latest search was carried out in November 2012.

Selection criteria

We included randomised trials of influenza vaccination in children (over two years of age) and adults with asthma. We excluded studies involving people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Data collection and analysis

Inclusion criteria and assessment of trial quality were applied by two review authors independently. Data extraction was done by two review authors independently. Study authors were contacted for missing information.

Main results

Nine trials were included in the first published version of this review, and nine further trials have been included in four updates. The included studies cover a wide diversity of people, settings and types of influenza vaccination, and we pooled data from the studies that employed similar vaccines.

Protective effects of inactivated influenza vaccine during the influenza season

A single parallel‐group trial, involving 696 children, was able to assess the protective effects of influenza vaccination. There was no significant reduction in the number, duration or severity of influenza‐related asthma exacerbations. There was no difference in the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) although children who had been vaccinated had better symptom scores during influenza‐positive weeks. Two parallel‐group trials in adults did not contribute data to these outcomes due to very low levels of confirmed influenza infection.

Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine in the first two weeks following vaccination

Two cross‐over trials involving 1526 adults and 712 children (over three years old) with asthma compared inactivated trivalent split‐virus influenza vaccine with a placebo injection. These trials excluded any clinically important increase in asthma exacerbations in the two weeks following influenza vaccination (risk difference 0.014; 95% confidence interval ‐0.010 to 0.037). However, there was significant heterogeneity between the findings of two trials involving 1104 adults in terms of asthma exacerbations in the first three days after vaccination with split‐virus or surface‐antigen inactivated vaccines. There was no significant difference in measures of healthcare utilisation, days off school/symptom‐free days, mean lung function or medication usage.

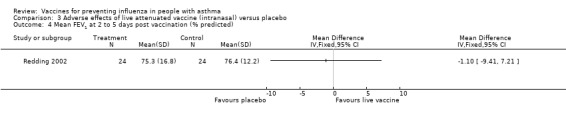

Effects of live attenuated (intranasal) influenza vaccination

There were no significant differences found in exacerbations or measures of lung function following live attenuated cold recombinant vaccine versus placebo in two small studies on 17 adults and 48 children. There were no significant differences in asthma exacerbations found for the comparison live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular) in one study on 2229 children (over six years of age).

Authors' conclusions

Uncertainty remains about the degree of protection that vaccination affords against asthma exacerbations that are related to influenza infection. Evidence from more recently published randomised trials of inactivated split‐virus influenza vaccination indicates that there is no significant increase in asthma exacerbations immediately after vaccination in adults or children over three years of age. We were unable to address concerns regarding possible increased wheezing and hospital admissions in infants given live intranasal vaccination.

Plain language summary

Vaccines for preventing flu in people with asthma

Asthma is a condition that affects the airways – the small tubes that carry air in and out of the lungs ‐ and the symptoms are generally coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath and chest tightness. The symptoms can be occasional or persistent. When a person with asthma breathes in an asthma trigger (something that irritates their airways), the muscles around the walls of the airways tighten so that the airways become narrower and the lining of the airways becomes inflamed and starts to swell. For many people with asthma, cold and flu viruses trigger their symptoms. Therefore, getting a flu virus makes their asthma worse and having a flu jab (influenza vaccine) may protect people against some of the flu viruses that they will come into contact with in a given winter. However, the effects of a flu jab (vaccination) are not straightforward as there is also the possibility that the flu jab itself could cause a worsening of asthma. Current guidelines in the UK recommend that high‐risk groups such as people with severe asthma should have a flu jab each winter (NHS Choices); however, there is limited evidence for this approach.

In this review, we evaluated evidence from randomised trials (RCTs) in relation to potential benefits and harms of all types of influenza vaccination in adults and children (over the age of two years) with asthma.

One trial in 696 children assessed the benefits of injecting inactivated influenza vaccine (inactivated virus vaccines are the type currently used in the US and UK and cannot cause flu). There were no significant differences in the number of people experiencing an asthma attack (worsening of symptoms); however, there were better symptom scores (people reporting fewer asthma symptoms) in weeks in which children had a positive test for influenza, in those who had received the jab compared to those who did not.

Two trials involved 1526 adults and 712 children who were given inactivated influenza vaccination, examined the harmful effects caused immediately after injection. These studies ruled out the likelihood of any more than four out of 100 people having a resultant asthma attack in the first two weeks after getting their flu jab. There was not enough information to compare different vaccination types.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo.

| Inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo for people with asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: children and adults with asthma Settings: community Intervention: inactivated influenza vaccine (intramuscular injection) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo | |||||

| Results from trials in children | ||||||

| Protection from experiencing an asthma exacerbation of any cause over the influenza season ‐ children (over 6 years of age) given inactivated influenza vaccine | 90 per 100 |

86 per 100 (81 to 90) |

See comment | 696 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Risks were calculated from risk difference in a single study (at low risk of bias) |

| Protection from experiencing an influenza‐related asthma exacerbation over the influenza season ‐ children (over 6 years of age) given inactivated influenza vaccine | 5 per 100 |

6 per 100 (3 to 9) |

See comment | 696 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Risks were calculated from risk difference in a single study (at low risk of bias) |

| Asthma exacerbation (adverse effects) caused by inactivated influenza vaccine, measured in the first 2 weeks following vaccination ‐ children (over 3 years of age) given inactivated influenza vaccine | 33 per 100 |

34 per 100 (29 to 38) |

See comment | 712 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | Risks were calculated from paired proportions in a single cross‐over study (at low risk of bias) |

| Results from trials in adults3 | ||||||

| Protection from experiencing an asthma exacerbation of any cause over the influenza season ‐ adults given inactivated influenza vaccine | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | 2 parallel‐group studies in adults did not contribute to this outcome due to low levels of influenza infection in the season following vaccination |

| Protection from experiencing an influenza‐related asthma exacerbation over the influenza season ‐ adults given inactivated influenza vaccine | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | 2 parallel‐group studies in adults did not contribute to this outcome due to low levels of influenza infection in the season following vaccination |

| Asthma exacerbation (adverse effects) caused by inactivated influenza vaccine, measured in the first 2 weeks following vaccination ‐ adults given inactivated influenza vaccine | 25 per 100 |

27 per 100 (24 to 29) |

See comment | 1526 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3 | Risks were calculated from pooled risk differences (from paired proportions in 2 cross‐over studies) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the mean control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the reported risk difference of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Single study on children with 95% CI that included no difference between vaccination and placebo.

2 95% CI from the pooled results of two studies excluded the pre‐specified threshold of a 6% increase in the number of participants with an asthma exacerbation following influenza vaccination.

3One trial at low risk of bias and one trial at unclear risk of bias.

Background

The primary goal of influenza vaccination policy has been the reduction of excess deaths associated with influenza epidemics (Barker 1982). Mortality statistics suggest that influenza may be associated with 3000 excess deaths per year in the UK alone and in epidemic years this may increase to as many as 18,000 (Ashley 1991). A large observational study in the US compared expected with observed mortality during seven influenza epidemics between 1957 and 1966 with similar results (Housworth 1974). These results have consistently demonstrated the majority of excess mortality during influenza outbreaks occurs in the elderly population. The major limitations of these studies involve a lack of a direct causal link between mortality and influenza infection and the biases inherent in their retrospective research methods (Patriarca 1994).

While there is still little evidence that influenza vaccination has an impact upon mortality, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of patients aged over 65 years without known risk factors has demonstrated a 50% reduction in serologically confirmed influenza infection (Govaert 1994). One review advocated immunisation of all patients aged over 65 years, irrespective of risk factor status (NHS CRD 1996), despite the lack of supporting evidence for this approach. However, the current policy in the UK and many other countries is to concentrate on those who are deemed to be at higher risk including those with severe asthma (NHS Choices 2011). Recommendations for asthmatics are not supported by evidence from RCTs, and provide no indication of which subgroups of patients with asthma, if any, should receive immunisation.

Observational studies have shown that exacerbations of asthma in children are often associated with viral infections; however, there is disagreement between studies on the relative importance of influenza compared to other viruses in this respect (McIntosh 1973; Roldaan 1982; Johnston 1995). To counter the argument that immunisation might benefit patients, the potential exists for influenza vaccination to precipitate an exacerbation in some asthmatics. This is one reason why some physicians remain reluctant to recommend the vaccine for people with asthma (Rothbarth 1995).

While the beneficial effect of influenza vaccine in people with asthma may be limited and there exists some concern about potential harm, other research suggests that some asthmatics who acquire influenza infections demonstrate reductions in pulmonary function (Kondo 1991). Therefore, immunisation has the potential to protect asthmatic patients from deterioration in lung function.

One previously published overview addressed the issue of influenza vaccination in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Rothbarth 1995). This review concluded that there was no clear benefit of influenza vaccination in patients with asthma and COPD. One review (Nicholson 2003) concluded that influenza vaccination is safe in asthma. However, these results were not based on a systematic search of the published and unpublished literature. Moreover, other methodological issues limit the validity of their conclusions.

This systematic review aims to systematically search for, and combine all evidence from, RCTs relating to the effects of influenza vaccination in asthmatic patients in order to generate the best available evidence on which to base recommendations for clinical practice and further research.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and harms of influenza vaccination in children and adults with asthma.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs with or without blinding.

Types of participants

We included asthmatic children (mean age greater than two years) and adults of all degrees of severity, irrespective of living arrangements (independent, institutional, etc.). We excluded studies reporting results on patients with COPD; however, we included data from studies of mixed populations if separate data on the asthmatic patients were available from the article or following contact with the authors.

Types of interventions

We included vaccination with any influenza vaccine including live, inactivated, whole, split virus, monovalent, bivalent, trivalent, polyvalent, A and B. We included the following comparison groups; placebo, no vaccine or another type of influenza vaccine.

Types of outcome measures

Protective effects of vaccination were measured during the influenza season (late benefits), while adverse effects caused by vaccination were measured in the first two weeks following vaccination (early adverse effects). We included the following outcomes measures under both categories:

asthma exacerbations;

admission to hospital (asthma related and from all causes);

pneumonia (confirmed by chest X‐ray);

asthma symptom scores, both in the two weeks and six months following immunisation;

lung function measurements (peak expiratory flow (PEF), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1); both absolute and % predicted), both in the two weeks and six months following immunisation;

number of visits to the emergency department or for other medical attention (excluding routine visits) concerning asthma in the two weeks and six months following immunisation;

number of rescue courses of corticosteroids (e.g. prednisolone, prednisone, dexamethasone or triamcinolone) in the two weeks and six months following immunisation;

mortality.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials (CAGR), which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (see Appendix 1 for further details). All records in the CAGR coded as 'asthma' were searched using the following terms:

((vaccin* or immuni*) and (influenza* or flu*)) or (flumist or trivalent or CAIV or LAIV or medimmune).

All databases were searched from their inception to the present and there was no restriction on language of publication or publication status. The most recent search was conducted in November 2012.

Searching other resources

We checked all references in the identified trials and contacted authors of included studies to identify any additional published or unpublished data. We also checked review articles for references to missed studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CJC and TOJ) assessed titles and abstracts identified from the computerised search. We obtained the full text of all potentially relevant citations for independent assessment by two review authors (CJC and AB), who identified studies for inclusion. We resolved disagreement by consensus. We contacted study authors for clarification where necessary.

Data extraction and management

Data on the trial characteristics and outcomes was extracted from the papers and entered into Review Manager (RevMan 2011) by one review author (CJC) and checked by a second review author (JS or CK).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CJC and EB), independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion between the review authors. Data were checked and entered onto the computer by one review author (CJC). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants and personnel;

blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting; and

other bias.

We graded each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear.

Measures of treatment effect

Weighted treatment effects (using random effects) were calculated across trials using the Cochrane statistical package, RevMan 2011. Dichotomous outcomes were expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) and risk difference (RD) with 95% CI. Continuous outcomes were calculated as weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95% CI. Analyses were performed on the benefits of vaccination over the full influenza season, and the short‐term harms experienced in the two weeks following vaccination.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials were included along with parallel group study designs in this review. The binary results were analysed using paired binomial proportions or discordant pairs, and the results combined with the parallel trials using the generic inverse variance method for the 2012 update. Analysis using paired data in this way was possible for Castro 2001 and Nicholson 1998; however, Kmiecik 2007 only provided descriptive statistics and was therefore analysed as if it was a parallel trial.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis of first time and repeat vaccinees were carried out where there were sufficient data.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were planned to compare the immediate and delayed response to whole virus and split virus vaccines in children and adults, as adverse reactions have been reported to be more frequent with whole virus vaccination in children. Comparison of the main outcomes in long‐term hospital care and those in the community were planned.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The original database search identified 36 abstracts for screening and 26 were selected for possible inclusion in the review. Two further papers were identified from references in other papers (Govaert 1992; Govaert 1994). The full text of each paper was obtained and translated when necessary (three from German). Papers were excluded for the following reasons: retrospective studies (five studies); not randomised (five studies); COPD (two studies) and no separate asthma data (five studies). Nine studies were included in this review with complete agreement between the two review authors. Two further studies had been identified for the first update of this review; one was excluded as it was not randomised (Ahmed 1997) and one new study was included (Reid 1998). Four further studies were identified for the second update and have been included (Sener 1999; Castro 2001; Redding 2002; Bueving 2003). One of these studies is the subject of three papers on different aspects of the trial (Castro 2001) and the other papers are shown as secondary references.

Further searches up to December 2007 identified 22 new abstracts; from these one large new study was included (Fleming 2006). Authors of two other large studies on young children were contacted (Ashkenazi 2006, Belshe 2007) to try to obtain data on the subset of children with asthma. All of the new included studies compared intranasal live attenuated vaccine to trivalent inactivated vaccine (TIV). Seven abstracts were publications relating to studies in this review, four were not randomised studies and one allocated patients to treatment by alternation (Chiu 2003). One small study was also excluded as it was not possible to contact the authors to clarify if randomisation occurred (Kim 2003).

A further search was carried out in November 2012, which identified 20 references to 16 trials. These were independently assessed by two review authors (CJC and JS or CK) and two new trials were included (Kmiecik 2007; Pedroza 2009). Five potentially relevant studies were excluded; two because they involved children without asthma (Ashkenazi 2006; Belshe 2007), two were not randomised (Piedra 2005; Andreeva 2007) and one because it compared two different doses of the same H1N1 influenza vaccination with no placebo arm (Busse 2011).

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies for details.

Nine studies were conducted in Europe (Hahn 1980; Stenius 1986; Ortwein 1987; Govaert 1992; Nicholson 1998; Sener 1999; Bueving 2003; Fleming 2006; Kmiecik 2007), two in Japan (Miyazaki 1993; Tanaka 1993) and five in the US and Mexico (Bell 1978; Atmar 1989; Castro 2001; Redding 2002; Pedroza 2009). The patients studied included children (Bell 1978; Miyazaki 1993; Tanaka 1993; Castro 2001; Redding 2002; Bueving 2003; Fleming 2006; Pedroza 2009) and adults (Stenius 1986; Atmar 1989; Govaert 1992; Nicholson 1998; Sener 1999; Castro 2001; Kmiecik 2007). Intramuscular injections of inactivated virus were most commonly studied but four trials (Atmar 1989; Miyazaki 1993; Tanaka 1993; Redding 2002) studied intranasal live vaccine. Three studies included randomised comparisons of different vaccine types (Ortwein 1987; Nicholson 1998; Fleming 2006).

Five studies (Bell 1978; Nicholson 1998; Sener 1999; Castro 2001; Kmiecik 2007) used cross‐over designs; all the others were parallel groups. All studies included some outcome measures for asthma exacerbation in the early post‐vaccination period, but only six studies looked for late outcomes to assess the protective efficacy of the vaccine (Stenius 1986; Govaert 1992; Miyazaki 1993; Tanaka 1993; Bueving 2003; Fleming 2006).

Risk of bias in included studies

Studies were not assigned as low risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel unless there was a clear indication that the placebo injection was similar in appearance to the active injection. This judgement was then applied retrospectively to the previously included studies and a summary of the 'Risk of bias' from all the studies is shown in Figure 1. On this basis, five studies had at least four of the five domains judged to be at low risk of bias (Stenius 1986; Govaert 1992; Nicholson 1998; Castro 2001; Bueving 2003). The late outcome data from Bell 1978 was not included as it was retrospective and not randomised.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Inactivated influenza vaccine (intramuscular injection) versus placebo

Protective effects of vaccination measured during the influenza season

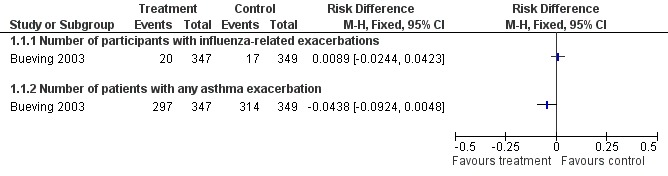

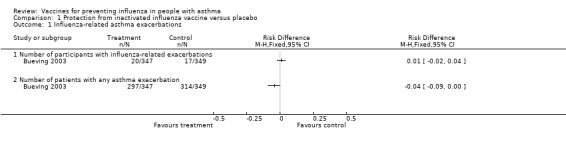

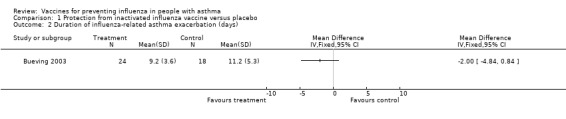

There was a single study, at low risk of bias, on 696 children reporting on the late benefits of inactivated vaccine compared with placebo that contributed data to the review (Bueving 2003). This study was conducted in the Netherlands over two influenza seasons and, in the 37 children who suffered asthma exacerbations related to positive throat swab identification of influenza virus, 20 were in the vaccinated group and 17 in the placebo group. This represented no change (RD 0.0089; 95% CI ‐0.024 to 0.042) with a narrow CI excluding a 6% absolute difference in exacerbations in the longer term following vaccination (Figure 2). It should be noted that a small proportion of exacerbations were related to confirmed influenza infection and when all exacerbations were considered the proportion of children in each group suffering an exacerbation was 85.5% in the vaccinated group and 90.1% in the placebo group; this represented an RD of ‐0.044 (95% CI ‐0.092 to 0.0048). The adjusted OR reported in the paper did not identify a significant difference between the groups (P = 0.10). The duration and severity of exacerbations were also not significantly different between the two groups.

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Protection from inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Influenza‐related asthma exacerbations.

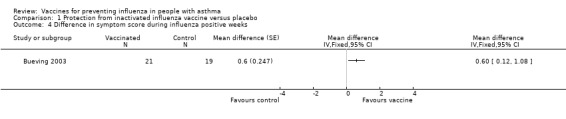

There was no significant difference in FEV1 (% predicted) during influenza positive weeks in 41 children (MD 9%; 95% CI ‐3.86% to 21.86%). In 40 children who tested positive for influenza and had asthma quality of life measurements, there was a statistically significant difference in the change in total scores in influenza‐positive weeks (MD 0.6; 95% CI 0.08 to 1.12). The total scores did not reach significance in "all illness" weeks. The number of patients with a change in quality of life score of at least 0.5 units (the minimally clinically important difference) was 10 (48%) in the vaccine group and 13 (68%) in the placebo group; however, this change only reached significance in the symptoms and activities domains and not in the total score. Nevertheless, these results do suggest a potential for influenza vaccination to be of benefit in increased asthma quality of life scores associated with test‐positive influenza in children.

Data from two studies could not be pooled. These studies were also designed to examine the late outcomes of influenza vaccination (Stenius 1986; Govaert 1992). In a study involving 328 adults, the incidence of influenza was low in Finland during the study and only one confirmed influenza infection was detected (Stenius 1986). No differences were found between the vaccinated and control groups in daily PEF measurements, symptom scores, daily medication use, and courses of oral corticosteroids or hospitalisation in the eight months following vaccination. In one other study for which data were available from the author for asthmatic patients (Govaert 1992), none of the 25 asthmatic patients had serologically confirmed influenza.

Adverse effects caused by vaccination measured in the first two weeks following vaccination

Combined results

Six studies contributed to the data for early adverse events, of which four studies were judged to be at low risk of bias (Stenius 1986; Nicholson 1998; Castro 2001; Bueving 2003). Data from Bueving 2003 have been included for the outcomes of bronchodilators, medical consultation and days off school; these data come from the report in Vaccine 2004.

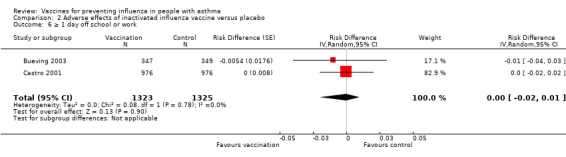

Two cross‐over trials (Castro 2001; Kmiecik 2007) involving 1526 adults and 712 children (over three years old) with asthma compared inactivated trivalent split‐virus influenza vaccine with a placebo injection. The pooled data excluded any clinically important overall increase in asthma exacerbations in the two weeks following influenza vaccination (RD 0.01; 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.04; Figure 3). The results in adults (RD 0.02; 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.05) and children (RD 0.01; 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.05) both excluded the pre‐specified increase in risk of six percentage points (Castro 2001). Castro 2001 was judged to be at low risk of bias, and exclusion of the results from Kmiecik 2007 (which was at unclear risk of bias and reported only descriptive statistics), made very little difference to the findings.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Split virus or surface antigen vaccine versus placebo (adverse events in first two weeks), outcome: 2.1 Asthma exacerbation within two weeks.

There was unexplained heterogeneity between the results of Castro 2001 and Nicholson 1998 in terms of the risk of asthma exacerbation in the first three days after influenza vaccination (RD 0.01; 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.05, I2 = 83%, Figure 4). The increased risk of exacerbation found in Nicholson 1998 was greatest in first‐time vaccinees (Figure 5), and no separate data were reported for the two different vaccines used in this study (split‐virus and surface vaccine). The heterogeneity between the results of Castro 2001 and Nicholson 1998 is significant (I2 = 83%). While further information has been requested from the authors of Nicholson 1998, particularly in relation to the two vaccines types used in this study, this information has not been provided. Information has been obtained from the other authors (Castro 2001) in relation to whether data are available about the previous vaccination status of the participants, indicating that first time vaccinees are not at increased risk of exacerbation in this study.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Split virus or surface antigen vaccine versus placebo (adverse events in first two weeks), outcome: 2.2 Asthma exacerbation within three days.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Split virus or surface antigen vaccine versus placebo (adverse events in first two weeks), outcome: 2.3 Asthma exacerbation within two weeks (subgrouped by previous vaccination status).

There were no significant differences found in hospital admissions from one study on 510 adults (Analysis 2.4) or symptom‐free days or days off work or school from one study involving 1952 adults and children (Analysis 2.5; Analysis 2.6). Medical consultation following vaccination was not increased in three studies involving 2894 adults and children (RD 0.00; 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.01). Similarly, no significant differences were found in lung function or use of rescue medication (Analysis 2.8; Analysis 2.9; Analysis 2.10; Analysis 2.11; Analysis 2.12).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 4 Hospital admission (0 to 14 days post vaccination).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 5 Number of symptom‐free days in 2 weeks after vaccination.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 6 ≥ 1 day off school or work.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 8 Patients at least 15% fall in FEV1 within 5 days.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 9 Fall in mean peak flow (% baseline) days 2 to 4.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 10 New or increased oral corticosteroid use (0 to 14 days after immunisation).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 11 Increased nebuliser usage within 3 days.

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 12 Increased use of rescue medication following vaccination (days 1 to 3).

Individual study results

In the earlier study on 262 patients (Nicholson 1998), there was a significant increase in the number of patients who suffered an exacerbation of asthma after inactivated split‐virus or surface antigen vaccine administration. This was defined as a fall in PEF of over 20%, in the first three days after injection (RD 0.031; 95% CI 0.03 to 0.058). Similarly, the number of patients with a fall of over 30% in their PEF in the first three days after active vaccination was significantly higher than after placebo (RD 0.031; 95% CI 0.007 to 0.054). In a subgroup analysis, excluding patients with 'common colds' from the analysis reduced the difference to statistically non‐significant, and subgroup analysis performed by the authors suggested that the majority of the exacerbations were observed in patients receiving vaccine for the first time. No other significant differences were found in the mean PEF, bronchodilator usage (via nebuliser or metered dose inhaler), hospital admission, medical consultations, oral corticosteroid usage or asthma symptoms. No significant difference was reported between the results for patients given split‐virus or subunit vaccines, but the authors have not been able to provide separate data for the two groups.

The subsequent large high‐quality study (Castro 2001) involving 2032 adults and children given inactivated influenza vaccination ruled out a significant increase in asthma exacerbations both for three days and for 14 days following vaccination. The pre‐defined significant difference was an absolute increase of 6% (RD 0.06) and this was outside the CI for this study and for the pooled result. It was also outside the CI of the pooled results for 30% fall in PEF, increased use of bronchodilators and oral corticosteroids, and unscheduled medical consultations for asthma. Significant increases in any of these outcomes were therefore excluded for inactivated influenza vaccination in this study.

In another study at low risk of bias, 318 patients were administered inactivated vaccine or placebo immunisation (Stenius 1986). No difference was found in the mean morning or evening PEF for the seven days after vaccination. No individual data on patients with a fall in PEF of over 20% were collected.

One study identified for the first update of this review (Reid 1998) compared mean FEV1 and airway responsiveness (PD20 methacholine) at 48 and 96 hours following injection of inactivated surface antigen in 17 adult asthmatic patients compared with five patients who were given placebo. No significant differences were found in the mean levels in either group and no patient had a change in PD20 of more than two‐fold.

One small cross‐over study in 24 volunteers with mild asthma (Sener 1999) found no increase in asthma symptoms or deterioration in lung function in the two weeks following vaccination with split antigen trivalent vaccine.

One early study, regarded by its authors as being preliminary (Bell 1978), identified a significant fall (‐12% from baseline, standard error (SE) 6%) in morning PEF at 48 hours after immunisation of children in a residential asthma care centre with inactivated influenza vaccine compared to a control group that received no vaccination. This was accompanied by a rise in nebuliser usage at 48 hours, but no change was observed in the afternoon PEF. The original data are no longer available (Bell, personal communication), and the published results cannot be used for meta‐analysis as control and treatment group data were not presented separately. Moreover, this was an open study with no placebo, randomisation by the patients' chart number and no checks for period effects were reported.

There were two other small studies in this group. No significant deterioration in home PEF measurement was reported by Hahn using split virus vaccine, subunit vaccine or placebo groups in the two weeks following vaccination, but no numerical data were provided (Hahn 1980). Govaert 1992 also reported no adverse symptoms from any of the 14 asthmatic patients immunised with split virus vaccine or the 11 asthmatic patients given placebo (data provided by author in response to a request for further information).

The data from Kmiecik 2007 were only reported using descriptive statistics, so we were incorporated the trial using a conservative approach (as if it were a parallel trial). Nine out of 286 adults experienced a severe asthma exacerbation in the 14 days after influenza vaccine compared to four out of 286 on placebo; this is reported as a difference of 1.7% ("descriptive statistics" in the paper reports 95% CI 1% to 2.7%, with no details of the derivation of this interval).

Live attenuated cold recombinant vaccine (intranasal) versus placebo

Protective effects of vaccination measured during the influenza season

Two studies in hospitalised children from Japan documented the protective effect of vaccination during influenza outbreaks on the ward, but neither reported any outcomes associated with asthma (Miyazaki 1993; Tanaka 1993). The authors did not respond to a request for further information.

Adverse effects caused by vaccination measured in the first two weeks following vaccination

One further study on 48 children was identified for the 2003 update (Redding 2002). There was no significant difference between groups in the primary outcome of the study (percentage change in % predicted FEV1). There was also no significant difference in the secondary outcomes of asthma exacerbations, number of participants with reduction in PEF of over 15% or over 30% and use of beta2‐agonists as rescue medication. A previously identified study (Atmar 1989) included 17 asthmatic patients. No significant differences were found in adults for hospital admission with asthma exacerbation, fall in mean FEV1, number of patients with exacerbation (fall in FEV1 of over 12% or 50 mL). This study also reported that none of the vaccine recipients reported an increase in bronchodilator therapy following vaccination, but no numerical data were provided. The pooled results from these two studies did not demonstrate a significant difference in the risk of a drop in FEV1 on days two to four after vaccination; however, the CI was wide due to small numbers of participants (RD 0.01; 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.15).

Two other studies in children (Miyazaki 1993; Tanaka 1993) reported that no asthma attacks were apparent following vaccination; however, no definition of asthma exacerbation was provided by the authors.

Inactivated whole virus versus split virus versus subunit vaccine

In the study that compared inactivated virus, split virus and subunit vaccine, the authors reported no significant difference in home PEF measurements in the three days following vaccination in any of the vaccine groups individually or together. They also reported that there was no deterioration in lung function measured in the laboratory in the three days following vaccination (Ortwein 1987). No numerical data were provided and numbers were small (24 to 28 in each group).

4. Live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular)

One large open‐label study used intranasal vaccine (cold‐adapted live attenuated influenza vaccine (CAIV‐T)) administered by a spray applicator delivering 1 mL to each nostril on 2229 participants aged six to 17 years (Fleming 2006). The comparison group was administered TIV by intramuscular injection. There was no placebo group.

Protective effects of vaccination measured during the influenza season

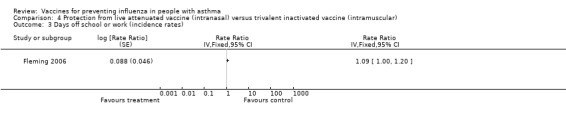

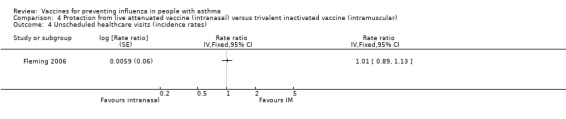

One single study, which was at risk of performance and detection bias, on 2229 children over six years of age contributed data to the review (Fleming 2006). Since there was no placebo arm in Fleming 2006 the absolute benefit of CIAV could not be assessed. In comparison with TIV, there was no significant difference in asthma exacerbations between intranasal and intramuscular vaccines over the full duration of the study (difference 1.6%; 95% CI ‐2.2 to 5.4%; Analysis 4.1). Out of 2229 participants, there were two hospitalisations for respiratory illness with TIV or CIAV; this was not a significant difference (OR 0.2; 95% CI 0.01 to 4.17) (Analysis 4.2). There was a marginally significant difference between groups for days off school (RR 1.09; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.2) (Analysis 4.3); however, significant differences for unscheduled healthcare visits or children with serious adverse events were not identified (1.8% with CIAV and 1.7% with TIV) (Analysis 4.4).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Protection from live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular), Outcome 1 Difference in incidence of asthma exacerbation over total study period.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Protection from live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular), Outcome 2 Hospitalisations due to respiratory illness.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Protection from live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular), Outcome 3 Days off school or work (incidence rates).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Protection from live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular), Outcome 4 Unscheduled healthcare visits (incidence rates).

Adverse effects caused by vaccination measured in the first two weeks following vaccination

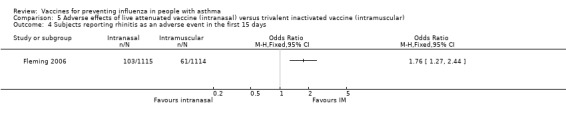

The single study on 2229 children reported harms caused by vaccination in the first two weeks following vaccination (Fleming 2006). In the first 15 days there was a significant increase in children reporting runny nose after the intranasal vaccine (66% versus 53%; OR 1.78; 95% CI 1.50 to 2.11) (Analysis 5.2), and the increase was also significant in those reporting rhinitis as an adverse event (9% versus 5%; OR 1.76; 95% CI 1.27 to 2.44) (Analysis 5.4). This has to be balanced against 60% of children who reported pain from the injection site with the intramuscular injection. In terms of bronchospasm reported as an adverse event there was no significant difference between groups (3% in both groups; OR 1.03; 95% CI 0.62 to 1.72) (Analysis 5.3). However, there were fewer cases of wheezing reported in the first 15 days with intranasal vaccine compared to injection of TIV (18% versus 22%; OR 0.79; 95% CI 0.64 to 0.97) (Analysis 5.1). No significant difference was found between exacerbation rates in the two groups over the first 42 days following vaccination (RD ‐0.1 percentage points; 95% CI ‐2.8 to 2.6).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular), Outcome 2 Subjects reporting runny nose or nasal congestion in the first 15 days.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular), Outcome 4 Subjects reporting rhinitis as an adverse event in the first 15 days.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular), Outcome 3 Subjects reporting bronchospasm as an adverse event in first 15 days.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular), Outcome 1 Subjects reporting wheeze in the first 15 days.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review examines the best available evidence regarding the effectiveness of influenza vaccination in patients with stable asthma. Despite employing an exhaustive search, few articles were identified that met the inclusion criteria. While this review is largely descriptive in nature, the potential for short‐term adverse effects and long‐term benefits can be summarised. There are now three cross‐over trials assessing the adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccination on asthma (Nicholson 1998; Castro 2001 at low risk of bias, and Kmiecik 2007 at unclear risk of bias). Overall, it is reassuring that the likelihood of an asthma exacerbation following influenza vaccination in adults and children (over the age of three years) is small, and that the absolute difference in risk of exacerbation between active vaccination and placebo lies between a 4% reduction and 5% increase, respectively. The excess of early exacerbations in one study (Nicholson 1998) following first‐time vaccination remains unexplained.

In contrast, the data from the trial on longer‐term benefit of influenza vaccination in the prevention of asthma exacerbations caused by exposure to influenza virus in the community have shown few significant benefits (Bueving 2003). The authors failed to demonstrate a significant benefit in children in the Netherlands in two seasons of exposure and the absolute benefit of vaccination from this trial lies between a 3% reduction and a 4% increase in exacerbations related to confirmed influenza infection. Again the CI excludes the pre‐determined 6% difference used by Castro in their power calculation (Castro 2001). The point estimate for the difference in all exacerbations was a 4% reduction in risk, but the CI included an increase of 0.05% and a decrease of 9% in risk difference. Consequently, there is no firm evidence from controlled clinical trials to support the adoption of universal vaccination in patients with asthma as a clinical policy. More information has been published on asthma symptoms during influenza positive illness weeks in Bueving 2003, indicating that the asthma quality of life scores in such weeks may be improved by influenza vaccination (in 40 of the 696 children who had confirmed influenza infection). Several new large studies have been identified comparing intranasal vaccine to intramuscular injection in children aged six to 17 years (Fleming 2006), and in infants from six to 72 months (Ashkenazi 2006; Belshe 2007). Although there was no indication of an increase in adverse respiratory outcomes in the older children, one of the studies on infants (Belshe 2007) has raised concerns over increased wheezing and hospital admissions following intranasal vaccination in the younger age group. A subsequent epidemiological survey (Miller 2012), from two of the cohorts in Belshe 2007 found that family history of asthma was a risk factor for wheezing after influenza vaccination in this study.

Quality of the evidence

Methodological limitations

1. The trials identified in this review represent a wide diversity of patients, settings and types of influenza vaccine. Initially most of the trials involved small numbers of patients; however, the review has now been strengthened by the addition of two new larger placebo‐controlled trials of high methodological quality (Castro 2001; Bueving 2003).

2. Influenza vaccination is administered at a time of year when upper respiratory viral infections are common; these can cause symptoms and asthma exacerbation that may occur soon after vaccination. The importance of a valid placebo control is demonstrated in one study (Atmar 1989) in which four of the six patients from the placebo group had an illness in the week following the vaccination. One patient from the placebo group was also admitted to hospital with an asthma exacerbation. This problem was addressed by other authors who re‐analysed their data after excluding patients with symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection in order to minimise the risk of including patients with exacerbations due to viral illness (Nicholson 1998).

3. Many studies did not report numerical outcomes for use of bronchodilator therapy and worsening of asthma symptoms. These data are therefore included in tables of results in the other data tables. Reports of "no significant difference" may hide small effects that become important when pooled; however, such comments are not useful without the data from which they are derived. Our attempts to contact the authors met with limited success, as most did not reply to a letter and a fax requesting further details.

4. The use of mean values for lung function data and asthma symptoms is of limited value as individual changes in important specific outcomes (i.e. asthma exacerbations or pulmonary function) may be missed.

5. The proportion of asthmatic patients who might contract influenza in a non‐pandemic winter may be small, and similarly the proportion suffering an adverse event from the vaccine may also be low. One study (Stenius 1986) identified only one serologically confirmed case of influenza among 157 asthmatics who were given a placebo vaccination. In another (Govaert 1994), none of the 11 asthmatic patients given placebo developed serologically confirmed influenza, and in the total 911 elderly patients given placebo only 9% went on to develop serologically confirmed infection. Of those patients who develop influenza, not all would be expected to develop asthma exacerbations. 6. Many other respiratory viruses can cause symptoms and asthma exacerbations. One observational study (Nicholson 1993) found that in 27 adults with viral infections leading to a fall of over 50 L/min in PEF, only one was due to confirmed influenza virus (compared to 16 in which human rhinovirus was confirmed). Similarly, in children aged nine to 11 years old, common cold viruses were identified in 80% of reported asthma exacerbations; influenza viruses were detected seven times less commonly in exacerbations (Johnston 1995). It is therefore important that any exacerbations following an influenza‐like illness are only regarded as being due to influenza if confirmed by a rise in antibody titre or virus detection, such as carried out in Bueving 2003.

Clinical practice

The potential impact of influenza vaccine will depend upon the frequency with which this virus causes acute exacerbations and infections in asthmatic individuals. This may also vary between epidemic/pandemic and non‐epidemic/non‐pandemic years. Such data are not available. Interpretation of the protective effects of influenza vaccines has to be viewed within this background.

Protective effect of vaccination

There are very limited data available from randomised trials to assess the protective effect of influenza vaccination in asthma. Only two studies of high quality used clinically important outcomes to test for a reduction in asthma exacerbations following influenza vaccination (Stenius 1986; Bueving 2003). Significant benefit in terms of reducing asthma exacerbations caused by influenza virus infection has not been demonstrated, although there is now a suggestion of a benefit in asthma quality of life scores in relation to episodes of proven influenza infection in a small number of children.

Comparison of vaccine types

Randomised comparisons of different vaccination types have been carried out in three studies looking for short‐term adverse effects (Hahn 1980; Ortwein 1987; Nicholson 1998); however, reporting of the outcomes was restricted to "no significant differences" found between groups.

Asthma exacerbation following vaccination

A higher incidence of asthma exacerbations following inactivated influenza vaccination was found in one study (Nicholson 1998), with a risk difference of 3.1% (95% CI 0.3 to 5.8) compared to placebo. This study was methodologically strong and was designed to identify patients in which common colds might explain the exacerbation. When patients with upper respiratory tract infections were excluded, the difference was no longer significant. It is not possible to say whether the risk difference was less, as the total number of patients excluded from each group due to colds was not reported. The authors concluded that the risk of exacerbation was low in comparison to the possible protective effect of the vaccine. This has not been borne out by the subsequent trial from the Netherlands (Bueving 2003). The large study on split virus vaccine (Castro 2001) gives reassurance in terms of the safely of this type of influenza vaccination. More recently three large studies in children (Ashkenazi 2006; Fleming 2006; Belshe 2007) have compared intranasal vaccine with intramuscular injection in infants and older children. It appears that in children aged six to 17 years of age, intranasal and intramuscular vaccines have similar profiles for asthma exacerbations and wheeze of sufficient severity to be considered an adverse event. Two further studies (Ashkenazi 2006; Belshe 2007) were found comparing intranasal vaccine with intramuscular vaccine in children from six to 71 months of age; some of these children had a clinical diagnosis of asthma and further information has been sought from the authors on this subgroup of children. At present these studies have not been included in this review. However, concern was raised in the Belshe 2007 study as the new intranasal vaccine was associated with an increase in hospital admissions of any cause in children from six to 11 months (6.1% versus 2.6% over 180 days; rate difference 3.5%; 95% CI 1.4 to 5.8), and more episodes of medically significant wheezing in the first 42 days following the vaccine (2.3% versus 1.5%; rate difference 0.77%; 95% CI 0.12 to 1.46).

Two other studies (Atmar 1989; Redding 2002) that measured individual exacerbations following recombinant vaccine demonstrated no significant difference between the vaccinated and placebo groups; however, the pooled results were underpowered to detect the risk difference of 3% found in the Nicholson study.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The evidence available from RCTs identified no significant reduction in the frequency of asthma exacerbations following influenza infection; however, one study has now demonstrated improved asthma quality of life scores in a small number of children with confirmed influenza infection.

Overall, influenza vaccination appears safe in adults and older children with asthma; a significant increase in asthma exacerbations immediately following split‐virus influenza vaccination has now been excluded. No significant difference has been identified between vaccine types in these age groups. However, there are insufficient trials and the number of patients upon which these comparisons are based is small.

Intranasal vaccination in children under two years of age may be associated with increased wheezing and hospital admission.

Implications for research.

Further large randomised trials are needed to determine whether there is a protective effect of influenza vaccination in ambulatory adults and children with stable asthma. The trial should have sufficient power to detect infrequent exacerbations (such as the 6% risk difference used by Castro 2001) due to the immunisation or influenza infection and changes in asthma quality of life in relation to proven influenza infection.

The infrequent nature of influenza illness among patients with asthma implies that studies with adequate sample size and sufficiently long follow‐up are required to add clarity to this important clinical question. Ideally more than one influenza season should also be studied, in view of the variation in vaccination and influenza infection serotypes from year to year.

Future trials should include an analysis of exacerbation rate using recognised methods and definitions for detecting asthma exacerbations and verification of influenza exposure. Other important asthma‐related outcomes should also be reported, such as hospital admission, rescue courses of oral corticosteroids and unscheduled attendance in primary care or emergency departments.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 23 November 2012 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | We updated the risk of bias tables and rewrote much of the review text. We updated the methodology used in the meta‐analysis of cross‐over trials. The conclusions of the review now include separate consideration of adverse events in adults and children. |

| 23 November 2012 | New search has been performed | We updated the literature search and included two new studies. Kmiecik 2007 was a cross‐over study involving 286 adults and Pedroza 2009 was a parallel group study involving 163 children. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1997 Review first published: Issue 3, 1998

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 December 2008 | Amended | Search methods edited. Search dates corrected. |

| 4 December 2008 | New search has been performed | This review was previously updated as follows: 2008 update: Three large new trials were identified comparing intranasal cold‐attenuated live vaccine with intramuscular inactivated vaccine. Fleming 2006 included 2300 children aged 6 to 17 years and found the impact on asthma to be similar in both groups. One of the studies in younger children (Belshe 2007) showed an increase in wheezing episodes and hospital admissions in the infants given intranasal vaccination. Children under two years of age are not included in this review so further information is being sought from the authors, to see if they can provide data on the older children. Meanwhile it may be wise to avoid intranasal vaccination in infants who are prone to wheezing. 2003 update: four new trials were included. The first, Castro 2001, was a large cross‐over trial (2032 asthmatic children and adults) that did not find an increase in adverse asthmatic events following inactivated influenza vaccine in the two weeks after vaccination. The second, Redding 2002, assessed the safety and tolerability of intra‐nasal vaccination in 48 children and adolescents with asthma (parallel‐designed trial) and found that it was safe and well‐tolerated. The third, Bueving 2003, carried out a longer‐term parallel‐design trial in 696 children with inactivated influenza vaccine, but did not find a significant difference in influenza related asthma exacerbations compared to placebo over the following five months. The fourth, Sener 1999, was a small cross‐over study on 24 volunteers with mild asthma that did not find deterioration in symptoms or lung function after influenza vaccination. 1999 update: this review was updated to include the results of one new study (Reid 1998). The results and implications for practice and research were not been altered. |

| 1 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 18 February 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The NHS Executive (North Thames) provided funding for Dr Cates to prepare the original version of this review. We would especially like to thank Tom Jefferson for co‐authoring the original review and initial updates, but who stepped down from the review byline in 2012. In addition we would like to acknowledge the assistance provided by the CARG staff (Steve Milan, Jane Dennis, Toby Lasserson and Karen Blackhall) in identifying the trials from the register and obtaining copies of the papers. We would also like to thank Klaus Linde for help with translation of the German papers and assessment of their methodological quality, and Jo Picot for assisting with trial selection and data extraction for the 2003 update. We would like to thank the following authors for responding to correspondence and supplying additional data for the review: Dr Robert Atmar, Dr Mario Castro, Dr Phile Govaert, Dr Brita Stenius‐Aarnalia, Dr Tom Bell, Jonathan Nguyen‐Van‐Tam, Dr Stephen Bourke, Jing‐Long Huang and Hans van der Wouden. We would like to thank Anna Bara for her contribution to the original review and Toby Lasserson for help with assessment of papers to include in the 2007 update. We would also like to thanks Joannie Shen (JS), Charlotta Karner (CK) and Elora Baishnab (EB) for their contributions to the 2012 update.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Sources and search methods for the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register (CAGR)

Electronic searches: core databases

| Database | Frequency of search |

| MEDLINE (Ovid) | weekly |

| EMBASE (Ovid) | weekly |

| CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library) | Quarterly (4 issues per year) |

| PsycINFO (Ovid) | Monthly |

| CINAHL (Ebsco) | Monthly |

| AMED (Ebsco) | Monthly |

Handsearches: core respiratory conference abstracts

| Conference | Years searched |

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) | 2001 onwards |

| American Thoracic Society (ATS) | 2001 onwards |

| Asia Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR) | 2004 onwards |

| British Thoracic Society Winter Meeting (BTS) | 2000 onwards |

| Chest Meeting | 2003 onwards |

| European Respiratory Society (ERS) | 1992, 1994, 2000 onwards |

| International Primary Care Respiratory Group Congress (IPCRG) | 2002 onwards |

| Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) | 1999 onwards |

MEDLINE search strategy used to identify trials for the CAGR

Condition search

1. exp Asthma/

2. asthma$.mp.

3. (antiasthma$ or anti‐asthma$).mp.

4. Respiratory Sounds/

5. wheez$.mp.

6. Bronchial Spasm/

7. bronchospas$.mp.

8. (bronch$ adj3 spasm$).mp.

9. bronchoconstrict$.mp.

10. exp Bronchoconstriction/

11. (bronch$ adj3 constrict$).mp.

12. Bronchial Hyperreactivity/

13. Respiratory Hypersensitivity/

14. ((bronchial$ or respiratory or airway$ or lung$) adj3 (hypersensitiv$ or hyperreactiv$ or allerg$ or insufficiency)).mp.

15. ((dust or mite$) adj3 (allerg$ or hypersensitiv$)).mp.

16. or/1‐15

17. exp Aspergillosis, Allergic Bronchopulmonary/

18. lung diseases, fungal/

19. aspergillosis/

20. 18 and 19

21. (bronchopulmonar$ adj3 aspergillosis).mp.

22. 17 or 20 or 21

23. 16 or 22

24. Lung Diseases, Obstructive/

25. exp Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/

26. emphysema$.mp.

27. (chronic$ adj3 bronchiti$).mp.

28. (obstruct$ adj3 (pulmonary or lung$ or airway$ or airflow$ or bronch$ or respirat$)).mp.

29. COPD.mp.

30. COAD.mp.

31. COBD.mp.

32. AECB.mp.

33. or/24‐32

34. exp Bronchiectasis/

35. bronchiect$.mp.

36. bronchoect$.mp.

37. kartagener$.mp.

38. (ciliary adj3 dyskinesia).mp.

39. (bronchial$ adj3 dilat$).mp.

40. or/34‐39

41. exp Sleep Apnea Syndromes/

42. (sleep$ adj3 (apnea$ or apnoea$)).mp.

43. (hypopnoea$ or hypopnoea$).mp.

44. OSA.mp.

45. SHS.mp.

46. OSAHS.mp.

47. or/41‐46

48. Lung Diseases, Interstitial/

49. Pulmonary Fibrosis/

50. Sarcoidosis, Pulmonary/

51. (interstitial$ adj3 (lung$ or disease$ or pneumon$)).mp.

52. ((pulmonary$ or lung$ or alveoli$) adj3 (fibros$ or fibrot$)).mp.

53. ((pulmonary$ or lung$) adj3 (sarcoid$ or granulom$)).mp.

54. or/48‐53

55. 23 or 33 or 40 or 47 or 54

Filter to identify RCTs

1. exp "clinical trial [publication type]"/

2. (randomised or randomised).ab,ti.

3. placebo.ab,ti.

4. dt.fs.

5. randomly.ab,ti.

6. trial.ab,ti.

7. groups.ab,ti.

8. or/1‐7

9. Animals/

10. Humans/

11. 9 not (9 and 10)

12. 8 not 11

The MEDLINE strategy and RCT filter are adapted to identify trials in other electronic databases

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Protection from inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Influenza‐related asthma exacerbations | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Number of participants with influenza‐related exacerbations | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Number of patients with any asthma exacerbation | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Duration of influenza‐related asthma exacerbation (days) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Severity of influenza‐related asthma exacerbation (symptom score) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Difference in symptom score during influenza positive weeks | 1 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Proportion of patients with minimum important difference in total symptom score (influenza‐positive weeks) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 FEV1 (% predicted) during influenza positive weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Protection from inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 1 Influenza‐related asthma exacerbations.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Protection from inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 2 Duration of influenza‐related asthma exacerbation (days).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Protection from inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 3 Severity of influenza‐related asthma exacerbation (symptom score).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Protection from inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 4 Difference in symptom score during influenza positive weeks.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Protection from inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 5 Proportion of patients with minimum important difference in total symptom score (influenza‐positive weeks).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Protection from inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 6 FEV1 (% predicted) during influenza positive weeks.

Comparison 2. Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Asthma exacerbation within 2 weeks | 2 | 2238 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.01, 0.04] |

| 1.1 Adults | 2 | 1526 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.01, 0.05] |

| 1.2 Children | 1 | 712 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.04, 0.05] |

| 2 Asthma exacerbation within 3 days | 2 | 2212 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.03, 0.05] |

| 3 Asthma exacerbation within 2 weeks (subgrouped by previous vaccination status) | 2 | 2206 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.02, 0.04] |

| 3.1 First‐time vaccinees | 2 | 474 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.03, 0.12] |

| 3.2 Repeat vaccinees | 2 | 1732 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.02, 0.01] |

| 4 Hospital admission (0 to 14 days post vaccination) | 1 | Risk Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Number of symptom‐free days in 2 weeks after vaccination | 1 | Mean Difference (Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 ≥ 1 day off school or work | 2 | 2648 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.02, 0.01] |

| 7 Medical consultation (0 to 14 days after immunisation) | 3 | 2894 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | 0.00 [‐0.01, 0.01] |

| 8 Patients at least 15% fall in FEV1 within 5 days | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8.1 First dose of vaccination | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.2 Second dose of vaccination | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 9 Fall in mean peak flow (% baseline) days 2 to 4 | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10 New or increased oral corticosteroid use (0 to 14 days after immunisation) | 2 | 2209 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | 0.00 [‐0.01, 0.02] |

| 11 Increased nebuliser usage within 3 days | 1 | Risk Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 12 Increased use of rescue medication following vaccination (days 1 to 3) | 4 | 2810 | Risk Difference (Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.02, 0.01] |

| 13 Change in airways responsiveness | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 14 Change in asthma symptoms in the week following vaccination | Other data | No numeric data |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 1 Asthma exacerbation within 2 weeks.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 2 Asthma exacerbation within 3 days.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 3 Asthma exacerbation within 2 weeks (subgrouped by previous vaccination status).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 7 Medical consultation (0 to 14 days after immunisation).

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 13 Change in airways responsiveness.

| Change in airways responsiveness | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Kut 1999 | No significant change in PC20 following either placebo or vaccine. PC20 (SD) in the placebo group was 7.02 (9.3) before challenge and 7.3 (3.6) after 24 hours. In the vaccine group PC20 was 9.5(10.6) before vaccine and 9.8(9.3) afterwards. (P>0.05) |

| Reid 1998 | No significant difference found in placebo group (n=5) or vaccination group (n=17) in either mean PD20 or mean FEV1 (tested by analysis of variance ANOVA). No individual patient in either group showed a change of PD20 of more than two‐fold. |

| Sener 1999 | No significant difference between placebo and vaccine in PD20 at 2 weeks. Vaccine 2.96(SD 3.2) and placebo 2.76 (SD 2.91) |

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse effects of inactivated influenza vaccine versus placebo, Outcome 14 Change in asthma symptoms in the week following vaccination.

| Change in asthma symptoms in the week following vaccination | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Govaert 1992 | No adverse reactions on asthma symptoms reported from any of the 14 asthmatics immunised with split‐virus vaccine or the 11 astmatics given placebo. (Communication from author) |

| Hahn 1980 | No significant deterioration in home Peak Flow measurement in the split vaccine (25 patients), subunit vaccine (25 patients) or placebo group (16 patients) in the two weeks following vaccination. No numerical data given. |

| Sener 1999 | No significant difference in symptom scores in the week after vaccine. Placebo mean score 4.66 (SD 7.3), vaccine mean score 4.92 (SD 7.56) |

| Stenius 1986 | Similar in the vaccine and placebo groups. No numerical data provided. |

Comparison 3. Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hospital admission for asthma exacerbation | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Asthma exacerbations in the month after vaccination | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Asthma exacerbations in the week following vaccination | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4 Mean FEV1 at 2 to 5 days post vaccination (% predicted) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Number of patients with significant fall in FEV1 (over 12% to 15% or 50 mL) on day 2 to 4 | 2 | 65 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.12, 0.15] |

| 6 Fall in mean FEV1 (L) (day 2 to 4) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7 Number of puffs of beta2‐agonist per day (in month following vaccination) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8 Morning peak flow of greater than 30% below baseline at least once in the 4 weeks after vaccination | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus placebo, Outcome 1 Hospital admission for asthma exacerbation.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Asthma exacerbations in the month after vaccination.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus placebo, Outcome 3 Asthma exacerbations in the week following vaccination.

| Asthma exacerbations in the week following vaccination | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Miyazaki 1993 | No asthma attacks were apparent following vaccination. Evaluation was made difficult by an Adenovirus outbreak during the study period. No defintion of asthma attack provided by the authors. |

| Tanaka 1993 | No asthma attacks were observed following vaccination (20 patients given CR vaccine and 25 given placebo). No defintion of asthma attack provided by the authors. |

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Mean FEV1 at 2 to 5 days post vaccination (% predicted).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus placebo, Outcome 5 Number of patients with significant fall in FEV1 (over 12% to 15% or 50 mL) on day 2 to 4.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus placebo, Outcome 6 Fall in mean FEV1 (L) (day 2 to 4).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus placebo, Outcome 7 Number of puffs of beta2‐agonist per day (in month following vaccination).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus placebo, Outcome 8 Morning peak flow of greater than 30% below baseline at least once in the 4 weeks after vaccination.

Comparison 4. Protection from live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Difference in incidence of asthma exacerbation over total study period | 1 | % Rate difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Hospitalisations due to respiratory illness | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Days off school or work (incidence rates) | 1 | Rate Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Unscheduled healthcare visits (incidence rates) | 1 | Rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Children with serious adverse events | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Protection from live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular), Outcome 5 Children with serious adverse events.

Comparison 5. Adverse effects of live attenuated vaccine (intranasal) versus trivalent inactivated vaccine (intramuscular).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Subjects reporting wheeze in the first 15 days | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Subjects reporting runny nose or nasal congestion in the first 15 days | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Subjects reporting bronchospasm as an adverse event in first 15 days | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Subjects reporting rhinitis as an adverse event in the first 15 days | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Atmar 1989.

| Methods | Randomisation: no details Blinding: double‐blind, but no details of method used Number excluded: no details Withdrawals: 2 (1 from each group due to extraneous viral infection) Baseline characteristics: antibody levels to influenza A and B measured and baseline lung function tests | |

| Participants | Location: Houston, TX Participants: 19 healthy adult volunteers with a history of asthma. 17 had data analysed, 11 given vaccine and 6 placebo Asthma definition and severity: history of intermittent wheezing, 15 patients using intermittent or continuous bronchodilator therapy Exclusion criteria: acute respiratory illness, allergy to egg, pregnancy | |

| Interventions | Vaccine type: intranasal bivalent (H3N2+H1N1) influenza A vaccine. 0.25 mL per nostril Placebo: allantoic fluid, 0.25 mL per nostril | |

| Outcomes | Early: lung function tests on days 0, 3 or 4, and 7; performed in the mornings (no bronchodilators taken before testing). The authors regarded a reduction in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 13% (or greater) from baseline to be clinically significant Bronchodilator therapy and hospital admission were also reported | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Generated by statistical group in General Clinical Research Centre |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Double‐blind but no details of similarity between placebo and active vaccine |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No drop‐outs reported |

Bell 1978.

| Methods | Randomisation: by hospital number Blinding: none (cross‐over with no placebo) Number excluded: no details Withdrawals: none Baseline characteristics: not compared | |