Abstract

In a recently published study, we developed a simple methodology to monitor Escherichia coli cell integrity and lysis during bioreactor cultivations, where we intentionally triggered leakiness. In this follow‐up study, we used this methodology, comprising the measurement of extracellular alkaline phosphatase to monitor leakiness and flow cytometry to follow viability, to investigate the effect of process parameters on a recombinant E. coli strain producing the highly valuable vascular endothelial growth factor A165 (VEGF‐A165) in the periplasm. Since the amount of soluble product was very little (<500 μg/g dry cell weight), we directly linked the effect of the three process parameters temperature, specific uptake rate of the inducer arabinose and specific growth rate (μ) to cell integrity and viability. We found that a low temperature and a high μ were beneficial for cell integrity and that an elevated temperature resulted in reduced viability. We concluded that the recombinant E. coli cells producing VEGF‐A165 in the periplasm should be cultivated at low temperature and high μ to reduce leakiness and guarantee high viability. Summarizing, in this follow‐up study we demonstrate the usefulness of our simple methodology to monitor leakiness and viability of recombinant E. coli cells during bioreactor cultivations.

Keywords: Alkaline phosphatase, Flow cytometry, Monitoring, Outer membrane integrity, VEGF‐A165

Abbreviations

- AP

alkaline phosphatase

- DCW

dry cell weight [g/L]

- DoE

design of experiments

- FCM

flow cytometry

- μ

specific growth rate [1/h]

- PP

periplasmic space

- qs_ara

specific uptake rate of the inducer arabinose [g/g/h]

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

1. Introduction

Escherichia coli is the most widely used microbial host for recombinant production of therapeutic proteins. About 30% of all FDA‐approved therapeutic proteins are currently produced in this prokaryotic organism 1, 2. E. coli provides many advantages as it can be cultivated on inexpensive media to high cell densities, an increasingly large number of molecular manipulation tools is constantly being developed and a library of different host strains, engineered for specific purposes, is available 1, 3, 4. One significant disadvantage of this host, however, is its lack of performing posttranslational modifications, like the correct formation of disulfide bonds in the cytoplasm and glycosylation. Nevertheless, many high valuable biopharmaceuticals, such as antibody fragments and growth factors, do not require glycosylation for proper folding and biological activity and thus can be expressed in E. coli. However, a lot of these biopharmaceuticals carry disulfide bonds, which is why they have to be expressed in the oxidative environment of E. coli’s periplasm to be correctly folded 5. In that case, the bioprocesses have to be carefully designed and monitored, since it is well known that E. coli gets leaky or even dies and lyses in response to metabolic burden and process parameters and consequent stress 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. Lysis has to be avoided, since it does not only result in tremendous product loss, but also leads to problems during cultivation (e.g. foam formation, overfeeding of cells) and complicates the subsequent downstream process. Cell leakiness, however, is a double‐edged sword: in case leakiness happens uncontrolled, it also leads to loss of periplasmic product and thus has to be avoided or at least kept at a minimum. On the other hand, if leakiness can be intentionally triggered, it describes a smart way to harvest periplasmic product, since most of the contaminating host cell proteins remain within the cell. In a recently published study, we investigated different methods to intentionally trigger periplasmic release during bioreactor cultivations by means of permeabilization agents, heat treatment, and combinations thereof 6. In fact, we were able to intentionally trigger the release of up to 30% of the periplasmic product (i.e. the model enzyme horseradish peroxidase). We also tested different methods to monitor leakiness and lysis and came up with a combination of (1) extracellularly measuring the enzyme alkaline phosphatase (AP) to follow leakiness, and (2) doing β‐galactosidase measurements and flow cytometry (FCM) to monitor viability and lysis 6.

In this follow‐up study, we demonstrate the applicability of this simple methodology, the combination of AP measurements and FCM, to monitor leakiness and cell viability in response to process parameters for a recombinant E. coli strain producing a highly valuable product in the periplasm. For that purpose we cultivated a strain producing the vascular endothelial growth factor VEGF‐A165 in a series of controlled bioreactor cultivations, where we varied the process parameters temperature (22°C–35°C), specific uptake rate of the inducer arabinose (qs_ara; 0.025–0.1 g/g/h) and specific growth rate (μ; 0.05–0.15 h−1) following a multivariate full factorial screening design. Summarizing, we were able to easily monitor the effects of these process parameters on E. coli cell integrity and viability and thus demonstrated the use of our simple methodology for bioprocess monitoring.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strain

E. coli strain C41 DE3 (Lucigen; Middleton, WI, USA) was used for the production of VEGF‐A165. The respective gene was cloned into a vector derived from the pBAD/GIII system (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA) using the tight regulation of the araBAD promoter 12, 13, 14. The signal sequence GIII allowed posttranslational transport of the product to the periplasmic space 15, 16.

2.2. Impact of process parameters on cell integrity—Design of experiments

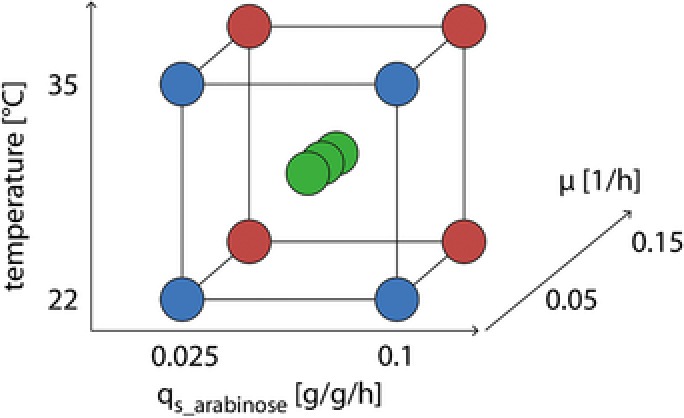

We analyzed the effect of the process parameters temperature, μ and qs_ara on the integrity of recombinant E. coli cells producing VEGF‐A165 in the periplasm. Therefore, we performed a full factorial design of experiments (DoE) screening study using the program MODDE (Umetrics; Umea, Sweden). In the DoE we analyzed the effect of the three factors temperature (22°C–35°C), μ (0.05–0.15 h−1), and qs_ara (0.025–0.1 g/g/h) on cell integrity and viability resulting in 11 controlled bioreactor cultivations (Fig. 1, Supporting Information Table S1). The limits of the factors were chosen based on previous studies 13, 17, 18. We had found that the specific productivity, though for another product, increased between qs_ara 0.025 and 0.11 g/g/h, but then decreased at higher levels 13. Thus, we set the limits of qs_ara with 0.025–0.10 g/g/h. With respect to temperature, we chose the lower limit with 22°C, since it is known that correct protein folding is enhanced at low temperatures 19, 20, 21. We chose 35°C as the upper limit to stay below 37°C where E. coli shows maximum metabolic activity and thus reduce metabolic load. Due to the complex procedure of posttranslational translocation of VEGF‐A165 to the periplasm caused by the GIII signal sequence, we speculated that μ might impact cell integrity and viability. Furthermore, it is well known that productivity in E. coli is growth related 13, 18. Thus, we included μ as factor in the range of 0.05–0.15 h−1. We chose the lower limit with 0.05 h−1 to potentially increase the amount of soluble product 18. The upper limit was set to 0.15 h−1 since this was the maximum μ at 22°C.

Figure 1.

Design space of the design of experiments screening study. The effects of the three factors qs_ara [g/g/h], temperature [°C], and μ [1/h] on cell integrity were analyzed.

2.3. Bioreactor cultivations

2.3.1. Bioreactor setup

Cultivations were carried out in a DASGIP multibioreactor system with four glass bioreactors and a working volume of 2 L each (Eppendorf; Hamburg, Germany). The DASGIP control software v4.5 revision 230 was used to control the process parameters pH (Hamilton; Reno, NV, USA), pO2 (Mettler Toledo; Greifensee, Switzerland; module DASGIP PH4PO4), temperature and stirrer speed (module DASGI PTC4SC4) as well as aeration (module DASGIP MX4/4). The pH was controlled with 12.5% NH4OH using pump module DASGIP MP8. CO2, O2, and mass flow in the off‐gas were quantified by a gas analyzer (module DASGIP GA4) using the nondispersive infrared and zircon dioxide detection principle, respectively.

2.3.2. Process design

All fed‐batch experiments comprised three phases: (1) batch on glucose, (2) noninduced fed‐batch on glucose, and (3) induced fed‐batch on a mix of glucose and arabinose. To reach the same amount of biomass and thus allow comparability, cultivations at a lower μ were run for a longer time according to the respective generation times (Supporting Information Fig. S1).

After the batch, resulting in a biomass concentration of 9 g/L dry cell weight (DCW), the uninduced fed‐batch was performed at a μ of 0.2 h−1 for 3.5 h corresponding to one generation and an increase of the DCW from 9 to 18 g/L. The induction phase was also conducted for one generation time to yield 36 g/L DCW. Different temperatures, μ and qs_ara were controlled according to the respective DoE setpoints (Fig. 1, Supporting Information Table S1) to investigate their impact on cell integrity and viability. Fed‐batch phases were controlled via feed forward exponential feeding as we described previously 13.

2.3.3. Media

Defined DeLisa medium was used in this study 22. d‐glucose was used as carbon source in the batch medium at a concentration of 20 g/L. The fed‐batch medium for the noninduced fed‐batch contained d‐glucose at a concentration of 400 g/L. For induction the fed‐batch medium contained d‐glucose and l‐arabinose at different ratios according to the DoE (Fig. 1, Supporting Information Table S1). The total concentration of carbon source in the feed was 400 g/L.

2.3.4. Cultivation procedure

100 mL precultures, inoculated from frozen stocks, were grown in 1000 mL baffled Erlenmeyer flasks in a shaking incubator at 35°C and 200 rpm for 11 h. Then, the preculture was aseptically transferred to the culture vessel. The inoculum volume was 10% of the final starting volume. Batch, noninduced fed‐batch and induction were performed at pH 7.2, a stirrer speed of 1600 rpm and an aeration rate of 90 L/h. The ratio of pure oxygen and air was adapted to maintain a dissolved oxygen level above 60% saturation. The temperature was kept at 35°C during batch and noninduced fed‐batch and was adjusted according to the DoE during induction (Fig. 1, Supporting Information Table S1).

2.4. Analytics

During cultivation, samples were taken and analyzed for biomass concentration, cell integrity, and viability 6.

2.4.1. Biomass

Samples (2 mL) were centrifuged (5000 g, 10 min) and pellets were washed with physiological NaCl solution. After drying at 105°C for 72 h, biomass concentration was quantified gravimetrically in triplicates.

2.4.2. FCM

FCM was carried out according to Langemann et al. 23. We used a CyFlow® Cube 6 flow cytometer (Partec; Münster, Germany) with 488‐nm blue solid‐state lasers. Three fluorescence channels were available (FL1, 536/40 nm bandpass; FL2, 570/50 nm bandpass; FL3, 675 nm longpass) alongside forward scatter (trigger parameter) and side scatter detection. The machine featured true volumetric absolute counting with a sample size of 200 μL. Data were collected using the software CyView 13 (Cube 6; Partec) and analyzed with the software FCS Express V.4.07.0001 (DeNovo Software; Los Angeles, CA, USA). Membrane potential‐sensitive dye DiBAC4(3) (abs./em. 493/516 nm) was used for the assessment of viability. Fluorescent dye RH414 (abs./em. 532/760 nm) was used for staining of plasma membranes yielding strong red fluorescent enhancement for the analysis of total cell number. Stocks of 0.5 mM DiBAC4(3) and 2 mM RH414 were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide and stored at –20°C. Both dyes were purchased from AnaSpec (Fremont, CA, USA). A 1.5 μL of both stocks were added to 1 mL diluted sample resulting in final concentrations of 0.75 μM DiBAC4(3) and 3.0 μM RH414, respectively. Samples were measured directly after addition of the dyes, without further incubation. By the combination of those two dyes it was possible to quantify all cells (RH414) and dead cells (DiBAC4(3)).

2.4.3. Alkaline phosphatase

Samples (1 mL) were centrifuged (5000 g, 10 min) and AP activity was determined in the cell‐free cultivation broth. 67 microliters supernatant were mixed with 133 μL of Tris buffer containing 4‐nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt hexahydrate (5 g/L in 100 mM TrisPufferan®; pH 8.5) as substrate. The formation of 4‐Nitrophenol was monitored in triplicates at 37°C at 405 nm in a plate reader (Tecan; Infinite M200 pro) in an interval of 150 s for 1.5 h. Volumetric AP activity was calculated according to Eq. (1) using a molar extinction coefficient of 18 000 M−1·cm−1.

| (1) |

Volumetric alkaline phosphatase activity [U/L]

- k

Slope of activity measurement [ΔAU/min]

- A

Molar extinction coefficient [1/M/cm]

- d

Path length through cuvette [cm]

- Vtotal

Total reaction volume [μL]

- Vsample

Sample volume [μL]

3. Results and discussion

The goal of this follow‐up study was to show the applicability of a recently developed methodology to distinguish between intact, leaky, and dead E. coli cells 6. We used this methodology to monitor cell integrity and viability of an E. coli strain producing the highly valuable product VEGF‐A165 in the periplasm in response to three different process parameters.

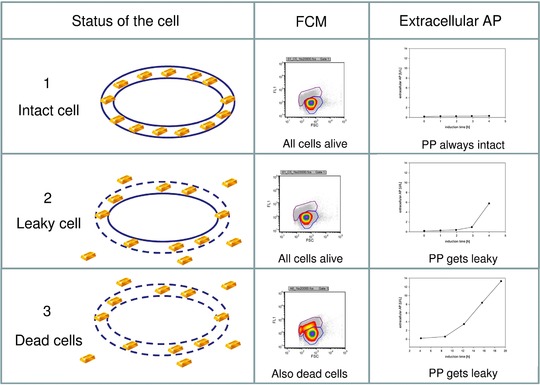

3.1. Monitoring methodology

FCM in combination with certain dyes allows to distinguish between viable and dead cells 23. However, no information about the integrity of the outer membrane can be gained therefrom. By measuring extracellular AP, a native protein in E. coli that can only be active in the periplasm 24, 25, 26, 27, the integrity of the outer membrane can be evaluated 28, however a differentiation between leaky and dead cells is not possible (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the responses used in the DoE screening experiment

| Response | Differentiate between | Morphological event |

|---|---|---|

| Dead cells [%] | Viable cell | Cells are viable, but no information on leakiness |

| Dead cell | Cells are dead, inner and outer membrane are not intact | |

| Extracellular AP [U/L] | Intact cell | Cells are viable and have intact outer membrane |

| Leaky cell | Outer membrane is leaky, but no information on viability |

By combining the two methods, FCM and extracellular AP measurements, which both can actually be implemented online 29, 30, 31 and thus answer to process analytical technology requirements (e.g. 32, 33), it is possible to monitor both cell leakiness and viability (Fig. 2), as we have also shown in a recently published study 6.

Figure 2.

A combination of FCM and the determination of extracellular AP allows differentiation between intact, leaky, and dead cells. Gold bars indicate the highly valuable product VEGF‐A165 in the periplasm (PP) of E. coli.

3.2. Impact of process parameters on cell integrity

In this follow‐up study, we wanted to demonstrate the use of our simple monitoring methodology to investigate the effect of different process parameters on cell integrity and viability of a recombinant E. coli strain producing VEGF‐A165 in the periplasm during bioreactor cultivations. Three of the key process parameters that are commonly used as regulating screws for E. coli bioprocesses are: (1) growth rate, (2) induction and (3) temperature. We expected to see effects of these three process parameters on productivity, cell integrity and viability. We wanted to link these three responses to each other, but finally also to the process parameters to generate process understanding. Thus, we conducted a multivariate DoE screening experiment comprising a total of 11 controlled bioreactor cultivations. However, the amount of soluble VEGF‐A165 in all these experiments was very low. We never exceeded a final product yield of 500 μg/g dry cell weight at the end of cultivation. In fact, we could only estimate the amount of soluble product by Western Blotting, which also revealed no trend in the data. Thus, we were not able to include the productivity as a response in our analyses. However, we believe that this very low amount of soluble product in the periplasm did not affect cell integrity by exceeding the capacity of the periplasm and assumed that leakiness and cell viability were a direct consequence of the process parameters.

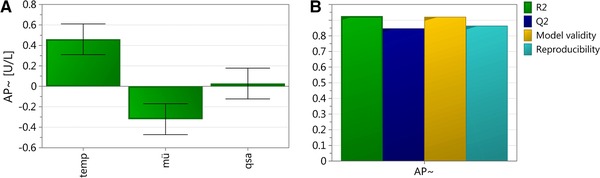

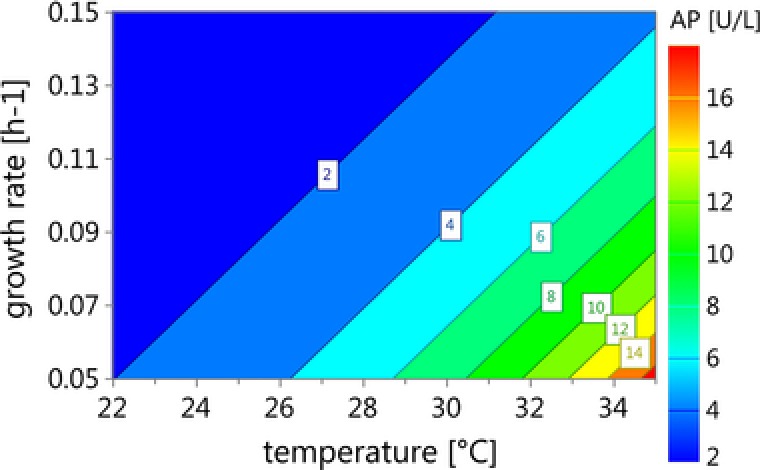

3.2.1. Leakiness

We found that the recombinant E. coli cells producing VEGF‐A165 in the periplasm became increasingly leaky with higher temperature during induction. We also found that a lower μ led to leakiness of the outer cell membrane. qs_ara was determined not to be a significant factor affecting leakiness, which we expected due to the very low amount of soluble product in the periplasm. Summarizing, both temperature and μ had a significant impact on leakiness. The model was valid with model statistics: R 2 = 0.93; Q2 = 0.85; Model validity = 0.93; Reproducibility = 0.87. In Fig. 3 the respective summary of fit plot and coefficient plot are shown. The respective contour plot summarizing the effect of temperature and μ on leakiness is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 3.

Results of the DoE for extracellular AP activity. (A) Summary of fit plot; (B) Coefficient plot. Error bars indicate the confidence level of the regression coefficients, evaluated from 11 performed experiments, which are significant when confidence interval does not cross zero.

Figure 4.

Contour plot of the factors temperature and μ and their effect on leakiness.

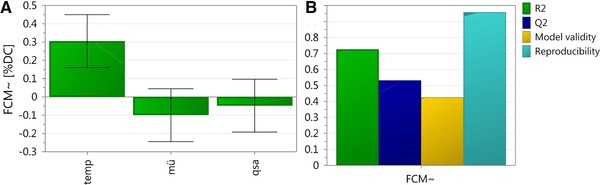

3.2.2. Viability

We found between 1–10% dead cells at the end of the different cultivations. The factor temperature was revealed to significantly affect viability, whereas μ and qs_ara had no significant impact. The model was valid with model statistics: R 2 = 0.73; Q2 = 0.53; Model validity = 0.43; Reproducibility = 0.96 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Results of the DoE for viability. (A) Summary of fit plot; (B) Coefficient plot. Error bars indicate the confidence level of the regression coefficients, evaluated from 11 performed experiments, which are significant when confidence interval does not cross zero.

As shown in Fig. 5, cell viability decreased with increasing temperature. This trend was also shown for leakiness. Thus, we concluded that the temperature was the most significant factor affecting both viability and integrity of the recombinant E. coli cells. We concluded that these cells should be cultivated at low temperature and high μ to reduce leakiness and guarantee high viability. Although we do not yet understand the physiological reasons for these phenomena, we could nicely demonstrate that two simple methods were sufficient to distinguish between intact, leaky, and dead cells and thus identify critical process parameters affecting leakiness and viability.

4. Concluding remarks

In a recent study we implemented a simple methodology to monitor leakiness and cell death of a recombinant E. coli strain producing a model enzyme in the periplasm. We measured extracellular AP to follow leakiness and did β‐galactosidase measurements and FCM to quantify viability during experiments where we intentionally triggered leakiness.

In this follow‐up study, we demonstrate the usefulness of this simple methodology to monitor cell integrity and viability for a recombinant E. coli strain producing the highly valuable product VEGF‐A165 in the periplasm during bioreactor cultivations. We actually used this simple methodology to multivariately investigate effects of the three process parameters μ, qs_ara, and temperature on leakiness and viability. Due to the very low amounts of soluble product in the periplasm we concluded that the stress for the E. coli cells leading to compromised outer membrane integrity and reduced viability was not a consequence of increased productivity and the resulting excess of periplasmic capacity, but directly linked the process parameters to cell integrity and viability. We concluded that E. coli producing VEGF‐A165 fused to GIII in the periplasm should be cultivated at low temperature and high μ to reduce leakiness and guarantee high viability. We believe that our simple methodology, that can be implemented online and answers to PAT criteria, is a nice tool for process monitoring, e.g. to determine the optimal time point of harvest.

Practical application

Numerous highly valuable products, like growth factors, and antibody fragments, are currently being produced in the oxidative environment of the periplasm of E. coli due to formation disulfide bridges. Uncontrolled leakiness of the outer membrane and reduced viability result in tremendous product loss. In this follow‐up study, we demonstrate the usefulness of a simple methodology, comprising the measurement of extracellular alkaline phosphatase (AP), and flow cytometry (FCM), to monitor leakiness and viability of recombinant E. coli during bioreactor cultivations. We believe that our simple methodology, that can be implemented online and answers to PAT criteria, is a useful tool for bioprocess monitoring, e.g. to determine the optimal time point of harvest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information Table S1. Experimental design for the DoE screening study.

Supporting Information Figure S1. Visualization of biomass trend and feed rate in the three cultivation phases (batch, fed‐batch, induction) for different specific growth rates.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the scientific input of Andrea Meitz, and Timo Langemann and the support of Philipp Doppler and Thomas Hartmann for carrying out the alkaline phosphatase activity measurements.

5 References

- 1. Baeshen, M. N. , Al‐Hejin, A. M. , Bora, R. S. , Ahmed, M. M. et al., Production of biopharmaceuticals in E. coli: Current scenario and future perspectives. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 953–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walsh, G. , Biopharmaceutical benchmarks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 992–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosano, G. L. , Ceccarelli, E. A. , Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: Advances and challenges. Front Microbiol. 2014, 5, 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sugiki, T. , Fujiwara, T. , Kojima, C. , Latest approaches for efficient protein production in drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2014, 9, 1189–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goemans, C. , Denoncin, K. , Collet, J. F. , Folding mechanisms of periplasmic proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 1517–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wurm, D. J. , Slouka, C. , Bosilj, T. , Herwig, C. et al., How to trigger periplasmic release in recombinant Escherichia coli: A comparative analysis. Eng. Life Sci. 2016, in press. DOI: 10.1002/elsc.201600168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lin, H. Y. , Hanschke, R. , Nicklisch, S. , Riemschneider, S. et al., Cellular responses to strong overexpression of recombinant genes in Escherichia coli, in: Merten O.‐W., Mattanovich D., Lang C., Larsson G., et al. (Eds.), Recombinant Protein Production with Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells. A Comparative View on Host Physiology, Dordrecht, Springer Netherlands: 2001, pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neubauer, P. , Winter, J. , Expression and fermentation strategies for recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli, in: Merten O.‐W., Mattanovich D., Lang C., Larsson G., et al. (Eds.), Recombinant Protein Production with Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells. A Comparative View on Host Physiology, Dordrecht, Springer Netherlands: 2001, pp. 195–258. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhu, J. , Thakker, C. , San, K.‐Y. , Bennett, G. , Effect of culture operating conditions on succinate production in a multiphase fed‐batch bioreactor using an engineered Escherichia coli strain. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 92, 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Striedner, G. , Cserjan‐Puschmann, M. , Pötschacher, F. , Bayer, K. , Tuning the transcription rate of recombinant protein in strong Escherichia coli expression systems through repressor titration. Biotechnol. Prog. 2003, 19, 1427–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rinas, U. , Hoffmann, F. , Selective leakage of host‐cell proteins during high‐cell‐density cultivation of recombinant and non‐recombinant Escherichia coli . Biotechnol. Prog. 2004, 20, 679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sagmeister, P. , Kment, M. , Wechselberger, P. , Meitz, A. et al., Soft‐sensor assisted dynamic investigation of mixed feed bioprocesses. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 1839–1847. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sagmeister, P. , Schimek, C. , Meitz, A. , Herwig, C. et al., Tunable recombinant protein expression with E. coli in a mixed‐feed environment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 2937–2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schleif, R. , AraC protein, regulation of the l‐arabinose operon in Escherichia coli, and the light switch mechanism of AraC action. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 779–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Denks, K. , Vogt, A. , Sachelaru, I. , Petriman, N. A. et al., The Sec translocon mediated protein transport in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2014, 31, 58–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Marco, A. , Strategies for successful recombinant expression of disulfide bond‐dependent proteins in Escherichia coli . Microb. Cell Fact. 2009, 8, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sagmeister, P. , Langemann, T. , Wechselberger, P. , Meitz, A. et al., A dynamic method for the investigation of induced state metabolic capacities as a function of temperature. Microb. Cell Fact. 2013, 12, 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shin, C. S. , Hong, M. S. , Kim, D. Y. , Shin, H. C. et al., Growth‐associated synthesis of recombinant human glucagon and human growth hormone in high‐cell‐density cultures of Escherichia coli . Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1998, 49, 364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Francis, D. M. , Page, R. , Strategies to optimize protein expression in E. coli . Curr. Protocols Protein Sci. 2010, 5, Unit 5.24.21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gopal, G. J. , Kumar, A. , Strategies for the production of recombinant protein in Escherichia coli . Protein J. 2013, 32, 419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Correa, A. , Oppezzo, P. , Tuning different expression parameters to achieve soluble recombinant proteins in E. coli: Advantages of high‐throughput screening. Biotechnol. J. 2011, 6, 715–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DeLisa, M. P. , Li, J. C. , Rao, G. , Weigand, W. A. et al., Monitoring GFP‐operon fusion protein expression during high cell density cultivation of Escherichia coli using an on‐line optical sensor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1999, 65, 54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Langemann, T. , Mayr, U. B. , Meitz, A. , Lubitz, W. et al., Multi‐parameter flow cytometry as a process analytical technology (PAT) approach for the assessment of bacterial ghost production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim, E. E. , Wyckoff, H. W. , Structure of alkaline phosphatases. Clin. Chim. Acta 1990, 186, 175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoffman, C. S. , Wright, A. , Fusions of secreted proteins to alkaline phosphatase: An approach for studying protein secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 5107–5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Michaelis, S. , Inouye, H. , Oliver, D. , Beckwith, J. , Mutations that alter the signal sequence of alkaline‐phosphatase in Escherichia coli . J. Bacteriol. 1983, 154, 366–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dubose, R. F. , Hartl, D. L. , Evolutionary and structural constraints in the alkaline‐phosphatase of Escherichia coli, in: Selander R. K., Clark A. G., Whittam T. S. (Eds.), Evolution at the Molecular Level, Sunderland, Sinauer Associates: 1991, pp. 58–79. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Witte, A. , Lubitz, W. , Biochemical characterization of φX174‐protein‐E‐mediated lysis of Escherichia coli . Eur. J. Biochem. 1989, 180, 393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dietzsch, C. , Spadiut, O. , Herwig, C. , On‐line multiple component analysis for efficient quantitative bioprocess development. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 163, 362–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Broger, T. , Odermatt, R. P. , Huber, P. , Sonnleitner, B. , Real‐time on‐line flow cytometry for bioprocess monitoring. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 154, 240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arnoldini, M. , Heck, T. , Blanco‐Fernandez, A. , Hammes, F. , Monitoring of dynamic microbiological processes using real‐time flow cytometry. PLoS One 2013, 8, e80117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for industry: PAT A framework for innovative pharmaceutical development, manufacturing, and quality assurance. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm070305.pdf (Accessed January 24, 2017).

- 33. Lawrence, X. Y. , Amidon, G. , Khan, M. A. , Hoag, S. W. et al., Understanding pharmaceutical quality by design. AAPS J. 2014, 16, 771–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Table S1. Experimental design for the DoE screening study.

Supporting Information Figure S1. Visualization of biomass trend and feed rate in the three cultivation phases (batch, fed‐batch, induction) for different specific growth rates.