Abstract

Crude proteins and pigments were extracted from different microalgae strains, both marine and freshwater. The effectiveness of enzymatic pre‐treatment prior to protein extraction was evaluated and compared to conventional techniques, including ultrasonication and high‐pressure water extraction. Enzymatic pre‐treatment was chosen as it could be carried out at mild shear conditions and does not subject the proteins to high temperatures, as with the ultrasonication approach. Using enzymatic pre‐treatment, the extracted proteins yields of all tested microalgae strains were approximately 0.7 mg per mg of dry cell weight. These values were comparable to those achieved using a commercial lytic kit. Ultrasonication was not very effective for proteins extraction from Chlorella sp., and the extracted proteins yields did not exceed 0.4 mg per mg of dry cell weight. For other strains, similar yields were achieved by both treatment methods. The time‐course effect of enzymatic incubation on the proteins extraction efficiency was more evident using laccase compared to lysozyme, which suggested that the former enzyme has a slower rate of cell disruption. The crude extracted proteins were fractionated using an ion exchange resin and were analyzed by the electrophoresis technique. They were further tested for their antioxidant activity, the highest of which was about 60% from Nannochloropsis sp. The total phenolic contents in the selected strains were also determined, with Chlorella sp. showing the highest content reaching 17 mg/g. Lysozyme was also found to enhance the extraction of pigments, with Chlorella sp. showing the highest pigments contents of 16.02, 4.59 and 5.22 mg/g of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and total carotenoids, respectively.

Keywords: Cell disruption, Enzymes, Microalgae, Pigments, Proteins

Abbreviations

- AA

antioxidant activity

- BBM

bold bassel medium

- DPPH

1,1‐diphenyl‐2‐picryl‐hydrazyl

- GAE

gallic acid equivalent

- M.C. sp.

isolated microalgae strain from Malaria Center, UAE

- TPC

total phenolic contents

1. Introduction

The search for compounds possessing bioactivities for possible pharmaceutical applications has seen a surge in recent years, with an emphasis on microalgae attracting a lot of attention 1. Microalgae have proven to be an important source of lipids suitable for biodiesel production, and hence, numerous studies have been focused on the extraction of lipids from microalgae for fuel purposes. Consequently, the potential of microalgae to produce proteins and other high‐value components and their extractions have received much less attention 2. Some compounds produced by microalgae such as antioxidants, antiviral, anti‐inflammatory, antimicrobials and antitumor agents have shown marked selectivity to respond to a wide diversity of molecular targets 3. In addition to these potentially valuable pharmaceutical agents, microalgae have been explored as potential sources for antioxidants and antimicrobial additives.

Several of the aforementioned compounds are proteins, which are either not found or present at much lower concentrations in other natural sources 4. These proteinaceous compounds from microalgae have also shown to exhibit cancer chemo‐preventive features at different stages of carcinogenesis 5.

Antioxidants, which are substances that have the ability to overcome the damaging effects of free radicals on human health, are an important theme in the pharmaceutical and food industry. Antioxidants are capable of preventing the destructive effect of oxidants by binding with their free radicals forms 6. There are natural and synthetic antioxidants, with the natural ones being safer. Phenolic compounds have been reported to be one of the main natural antioxidants. Turkmen et al. 7 have shown that the antioxidant activity of extract from tea leaves increases linearly with total phenolic contents (TPC). It is of interest in this work to assess the TPC found in the microalgae crude extracts.

In addition, the production of pigments from microalgae is of great scientific and commercial importance 8. Pigments derived from microalgae are promising natural high‐value compounds. These pigments, which include chlorophylls (green pigments) and carotenoids (yellow or orange pigments) have health‐promoting properties such as being vitamin precursors, antioxidants, immune enhancers and anti‐inflammatory agents 9. Accordingly, microalgae pigments can find commercial applications as new functional additives to food, as well as to pharmaceutical and cosmetic products.

There are other advantages in cultivating microalgae in addition to obtaining compounds with unique properties. Microalgae can utilize CO2 as the sole carbon source, which has the concurrent advantages of reducing harmful emissions. In addition, microalgae cultivation does not require the development of agricultural lands. The most important feature of microalgae is their ability to grow in saline water, which reduces freshwater loading, and relatively high temperatures that makes them ideal for dry climates.

Extracting a specific component from microalgae is often hindered by the intrinsic rigidity of its cell wall. To overcome this, the cells must be disrupted to facilitate the extraction process. Many cell disruption techniques have been tested including bead milling 10, ultrasonication 11, microwave radiation 12, cell homogenizer 13 and high‐pressure cell disruption 14. However, all these processes are either energy intensive or may subject the extract to excessive heat or shear.

Recently, cell disruption using lytic enzymes has gained popularity 15, due to their lower energy consumption and their ability to avoid the harsh conditions that proteins are subjected to in other techniques. To protect it against the environment, microalgae has rigid cell walls consist of either tri‐layered structures of cellulose and proteins with other components such as uronic acid, mannose, xylan, or trilaminar layers of algaenan and glycoproteins, with minerals 16. Several lytic enzymes can be used, such as cellulase that can effectively hydrolyze the cellulosic structure of the cell walls, and lysozyme that can hydrolyze the linkage between peptidoglycan residues 17. The present study focuses on evaluating the effect of different lytic enzymes on the efficiency of protein extraction from different microalgae strains of different cell wall macrostructures.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains and culture media

In this study, the effect of lytic enzymes on the extraction of protein from both freshwater and marine strains was investigated. The fresh water strains were Chlorella sp., Ankistrodesmus braunii and Pseudochlorococcum sp. and marine strains were Tetraselmis sp. and Nannochloropsis sp., obtained from a local marine research center in Umm Al‐Quwain, UAE. In addition, a freshwater strain, Scenedesmus sp., was kindly provided by Algal Oil Limited, Philippines and an indigenous microalgae strain isolated from Musaffah, Abu Dhabi was kindly provided by Prof. K. Salihi, New York University in Abu Dhabi, UAE, which was identified to be of Chlamydomonas strain. The selection of these strains was based on their availability on the day of inoculums collection. The freshwater strains were grown phototrophically in modified bold bassel medium (BBM) consisting of (mM): 8.82 NaNO3, 0.17 CaCl2•2H2O, 0.3 MgSO4•7H2O, 1.29 KH2PO4, 0.43 K2HPO4, 0.43 NaCl, 1 (mL/L) of Vitamin B12, and 6 (mL/L) of P‐IV solution that consisted of 2 Na2EDTA•2H2O, 0.36 FeCl3•6H2O, 0.21 MnCl2•4H2O, 0.37 ZnCl2, 0.0084 CoCl2•6H2O and 0.017 Na2MoO4•2H2O. Marine strains were grown in F/2 medium (32 ppt salinity) consisting of (μM); 880 NaNO3, 36 NaH2PO4•H2O, 106 Na2SiO3•9H2O, 1 (mL/L) of; vitamin B12, biotin vitamin and thiamine vitamin solutions and 1 (mL/L) of trance metal solution that consisted of (μM); 0.08 ZnSO4•7H2O, 0.9 MnSO4•H2O, 0.03 Na2MoO4•2H2O, 0.05 CoSO4•7H2O, 0.04 CuCl2•2H2O, 11.7 Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2•6H2O and 11.7 Na2EDTA•2H2O. The prepared media, excluding vitamins, were sterilized in an autoclave (Hirayama HV‐50, Japan) at 121°C for 15 min and cooled to room temperature prior to use. In addition, a mixed culture of microalgae was obtained from Ras Al‐Khaimah Malaria Center, UAE. This culture was segregated by serial dilutions followed by streaking on an agar medium surface and incubated until colonies appeared. Individual dominant colony was isolated and inoculated into a sterilized liquid medium of BBM, and hereinafter referred to as M.C. sp. Agar medium was prepared by mixing 2 % (wt %) of the agar nutrient (No. 1, LAB MTM) with prepared BBM in 250 mL flask and dissolved by heating, followed by sterilization. The sterilized medium was then poured into a Petri dish, which was followed by the algae streaking.

2.2. Enzymes and chemicals

Lysozyme from chicken egg white (activity > 40 000 U/mg) and cellulase from Trichoderma longibrachiatum (activity ≥ 1.0 U/mg) were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich, USA. The enzymes were stored below 8°C according to supplier's instructions. All other chemicals and reagents were also obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich.

2.3. Extraction processes

The microalgae cultivation started with an initial cell concentration of about 100–200 mg/L. Once the concentration exceeded 3 g/L, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7000 rpm for 15 min. The harvested cells were then pretreated by ultrasonication, enzymes or high‐pressure water, to enhance the proteins extraction.

2.3.1. Ultrasonication

One gram of wet harvested microalgae cells were mixed with 10 mL of distilled water using an ultrasoniocator (Q‐Sonica, USA) at 1000 W for 3 min (30 s cycles and 5 s resting time in ice). During the resting time, the sample was placed in ice to prevent overheating. At the end of the extraction, the cells were separated by centrifugation, using IEC‐CL Multispeed centrifuge (Model No. 11210913, France) at 6000 rpm for 25–30 min. The supernatant was collected for protein analysis.

2.3.2. High‐pressure water

High‐pressure water extraction experiments were carried in a 10 cm3 extraction cell using high‐pressure fluid extraction apparatus (ISCO, SFX 220, USA). The apparatus comprised of a syringe pump (Model 260D, ISCO, USA), heating chamber, an extractor with 10 cm3 stainless steel cell and a temperature controlled incubator. Pressure within the chamber was measured and controlled by an internal control system. In each run, 1 g of wet biomass was placed in the extraction vessel with 5/8″ filters placed at the top and bottom of the sample to prevent carryover of particles. Water flowed into the high‐pressure syringe pump and pressurized to the desired pressure of 500 bars, which is the highest pressure the pump can provide. When the desired pressure was reached, the extraction cell was filled with high‐pressure water and the extraction started. After 8 h, the cell was depressurized by opening elution valve. The aqueous solution was collected for protein analysis.

2.3.3. Enzymatic treatment

The wet harvested microalgae cells (1g) were mixed with 3.25 mL of enzymatic solution (1 mg/mL) and 7.5 mL 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution of suitable pH (pH 7 and pH 5 for lysozyme and cellulase pre‐treatments, respectively). Distilled water (9.25 mL) was then added to bring the volume to 20 mL and the mixture was incubated in water bath shaker (Model No. SCT‐106.026, USA) at 37°C and 100 rpm for 2, 4 and 16 h. The cells were separated by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 30 min and the supernatant was collected for protein analytic. It should be noted that the amount of protein in each enzyme solution used was first measured. The amount of extracted protein from the enzymatically treated microalgae was determined by subtracting the amount of protein in the enzyme solution from the total amount of measured protein.

2.4. Protein quantification

Protein concentration was determined using a Bio‐Rad protein assay kit. The crude extracted samples (2 mL) were mixed with 8 mL of Bio‐Rad Bradford reagent each. The absorbance of the mixture at 595 nm was then measured within 60 min using UV‐spectrophotometer (UV–1800, Shimadzu, Japan). A calibration curve of the standard protein (albumin from bovine serum 98%) solutions of known concentrations was used to determine the extracted proteins yield (defined as the amount of protein per dry weight biomass, attained using each extraction technique). The extracted proteins yields were compared to the total protein content determined by Bio‐Rad Protein Assay kit.

There were 45 harvested microalgae mass samples, collected from seven different strains and subjected to different extraction processes. All experiments were carried out in duplicates (two parallel identical samples of same wet weight from the same strain) were subjected to the same experimental conditions. The presented data were the averages of the duplicated runs.

2.5. Proteins fractionation and molecular weights determination

Protein fractionation was carried out using HiTrap Q HP (Prepacked Q Sepharose, High Performance strong ion exchange column). The columns were first washed with 5 mL wash buffer solution (20 mM Tris, pH 8.5), followed by 5 mL regeneration buffer (20 mM Tris, 1M NaCl, pH 8.5) and 10 mL wash buffer, according to manufacturer's instructions. The crude sample (2 mL) was first filtered using Whitman filter paper in a vacuum filtration apparatus. The filtrate (1.5 mL) was then injected into the column through a syringe filter (0.45 μm). Each column was then injected with 1.5 mL of different NaCl solutions (0.1–1.0 M). The eluted fractions were collected in separate Eppendorf tubes and their protein concentrations were estimated by measuring the absorbance values at 280 nm 18.

The molecular weights distribution of the extracted crude microalgae soluble proteins was estimated under denaturing conditions by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) using Mini‐PROTEAN Tetra vertical system. The crude extracted protein solutions (250 μL) from selected strains were mixed with 100 μL trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to precipitate the proteins. The solutions were centrifuged and the supernatants were discarded. The precipitated proteins were dissolved in 40 μL of water and 10 μL of 5× SDS solution, bringing the final concentration to 1× SDS. Approximately, 10 μL of the protein in 1× SDS solution were then loaded into the wells, which were previously loaded with 10% gel solution and 0.1 mL (10% w/v) SDS). After a running time of around 1 h, the proteins in the gel were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R‐250.

2.6. Antioxidant activity

The samples of extracted proteins from microalgae (lysozyme and ultrasonication treated) were tested for their antioxidant activity. The free radical scavenging activity of all the extracts was evaluated by 1,1‐diphenyl‐2‐picryl‐hydrazyl (DPPH) according to the method by Shen et al. 19. Briefly, 1 g of wet microalgae biomass from Nannochloropsis sp., Tetraselmis sp. and Chlamydomonas sp., was mixed with 10 mL of distilled water and ultrasonicated, as described in Section 2.3.1. The extracts (0.5 mL) were mixed with 3.3 mL of 0.5 mM solution of DPPH in ethanol each. The mixtures were shaken vigorously and then allowed to stand at room temperature for 120 min. The absorbance of each sample with DPPH was measured at 517 nm using a UV‐VIS spectrophotometer. A blank solution was prepared with the solvent solutions only, without the extracts. A control solution was also used which consists of 0.5 mM solution of DPPH in ethanol, without the extracted samples. Lower absorbance values of reaction mixture indicate higher free radical scavenging activity. Extract's scavenging capability to DPPH radical was calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

where AA% is the percentage of the antioxidant activity, A517 is the absorption at 517 nm. For comparison, the experiment was repeated with 0.5 mL protein extract from lysozyme treated cells of Nannochloropsis sp. for 8 h, as described in Section 2.3.3.

The DPPH scavenging percentage was calibrated against suitable concentrations of Trolox. A linear regression equation (Eq. (2)) between the Trolox concentration and its scavenging percentage has been determined, which showed a good linear relationship with R 2 = 0.994 20

| (2) |

2.7. Total phenolic content

The phenolic contents of the crude extracts were determined to verify the origin of the antioxidant activity of the extract; wither it was owing to co‐extracted phenolic compounds or of the proteins themselves. In addition, the TPC of the microalgae was determined due to the importance of their high antioxidant activity in therapeutic applications. TPC of the extracts was estimated colorimetrically according to the Folin–Ciocalteau method 21. The extracted samples (0.2 mL) were added to aqueous Folin–Ciocalteau reagent (1.50 mL, 1:10 v/v) and allowed to stand for 5 min at ambient temperature. After 5 min, 1.5 mL of 60 g/L sodium carbonate solution was added and allowed to react for 90 min at ambient temperature. The absorbance of each sample was recorded at 760 nm with an UV‐VIS spectrophotometer. A calibration curve of gallic acid with a range of concentrations from 0.005 to 0.05 mg/mL was prepared as phenolic compound standard for quantification of TPC of the extracts. The TPC was expressed as gallic acid equivalent per gram of initial microalgae dry weight (mg GAE gdry microalgae −1).

2.8. Pigments extraction

Cellular pigments were quantified using a spectrophotometric method after extraction with 80% acetone 9. One‐gram wet cell microalgae biomass was suspended in 3.25 mL enzymatic solution of predetermined concentration and added to phosphate buffer solution (7.5 mL 0.1 M of pH 7.0). The mixture was then incubated in water bath shaker (Model No. SCT‐106.026, USA) at 37°C and 100 rpm for 12 h and the cells were then separated by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 30 min. The separated biomass was resuspended in 1.6 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH = 7) and 6.4 mL 100% acetone solution (final concentration of acetone was 80%). The mixture was then incubated in the dark for 24 h and centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 30 min. This extraction process was repeated four times, and the extracts were combined together. The absorbance was measured using UV‐spectrophotometer (UV–1800, Shimadzu, Japan) at three different wavelengths, namely 470, 646 and 663, subsequently. The amount of pigments was calculated using the following equations 9:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where Ai is the absorption at different wavelengths., Ca and Cb are the chlorophyll a and b concentrations, respectively (μg/mL), Ct is the total carotenoids (μg/mL) and the subscript i is the wavelength

2.9. Experimental replication and reproducibility of the results

All experiments were carried out in parallel duplicates. Wet biomass was harvested by centrifugation, and equal amounts (1 g) were placed in separate flasks and subjected to the same experimental procedure, under the conditions. The collected samples from the duplicated experiment were analyzed, and average values of the results were then presented. The reproducibility of the experimental results was evaluated for the total 45 samples in groups according to their methods of extractions and their types. The standard deviations were represented as error bars in the figures and error values in the tables. P‐values were considered significant where p < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Protein extraction

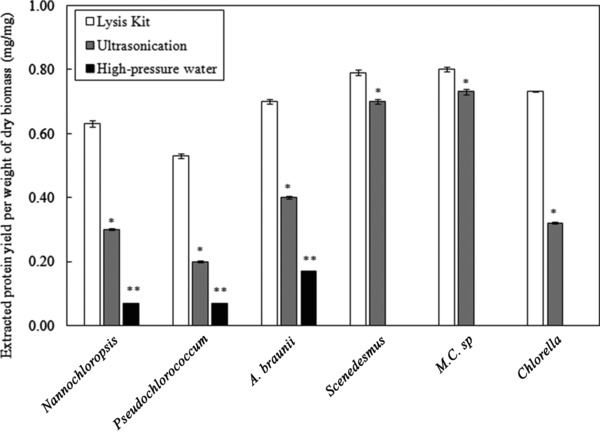

The study presented here compared the efficiency of different protein extraction techniques on different microalgae strains, grown under the same conditions. Figure 1 shows the results obtained using the lytic kit (detergent‐based solution) in comparison with the ultrasonication, high‐pressure water extraction methods and untreated cells. The reproducibility of the results is confirmed from the small error bars shown in the figure. The extracted amount of proteins from untreated cells was undetectable, which confirms the need for efficient cell disruption.

Figure 1.

Protein yield obtained from different microalgae strains treated with commercial lytic kit, ultasonication and high‐pressure water extraction. *Comparison between ultasonication and lytic kit: 0.01< p < 0.05 (significant). **Comparison between high‐pressure water and lytic kit: 0.001<p < 0.01 (very significant). The data presented are the average values of duplicated experiments, with the error bars showing the standard deviations.

The comparison of the extraction techniques has shown that the ultrasonication was superior to the high‐pressure water extraction. This was not surprising, as it required a pressure of 5400 bars to achieve a protein yield of about 0.55 g/g from Chlorella vulgaris 22. Nevertheless, this pressure was not attainable using the syringe pump used in this work, and the highest pressure that can be reached was 500 bar. Ultrasonication was effective with some strains, such as Scenedesmus sp. and M.C. sp., allowing extraction of more than 70% of the proteins. However, the ultrasonication was found to be less effective for other strains.

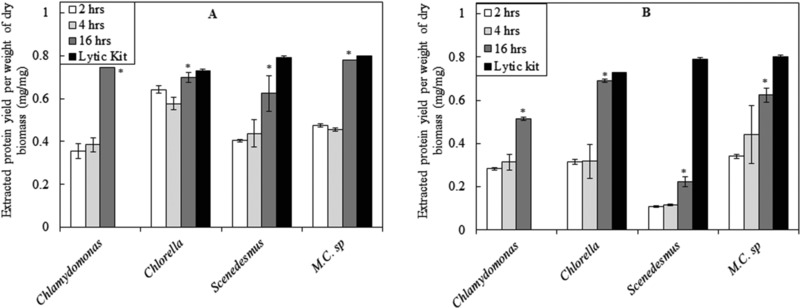

The detergent‐based lytic kit is very efficient in disrupting cells, which allows it to be used for determining the actual amount of protein in the cell. However, using this reagent denatured the proteins completely. On the other hand, ultrasonication is an easy method to execute and results in extracting high portions of the cells proteins. However, the use of this method is not preferable due to high power consumption and the heat generation during the process, which could result in protein denaturation. In addition, the probe has a short life time and needs to be replaced frequently. To overcome these problems, enzyme pre‐treatment has been proposed. The use of enzymes has the advantage of operating at mild conditions and low energy requirements. Figure 2 shows the protein yield achieved by using lysozyme and cellulase, respectively, on three selected microalgae, namely Chlorella sp., Scenedesmus sp. and M.C. sp, which have shown the highest protein yields, as shown in Fig. 1. In addition, the locally isolated strain, Chlamydomonas sp. was also tested. The reproducibility of the results was confirmed from the small error bars shown in the figure.

Figure 2.

Protein yield obtained from different microalgae strains treated with (A) lysozyme and (B) cellulase and compared to that extracted from the same strains treated with lytic kit. *Comparison between 4 and 16 h enzymatic treatments: 0.01< p < 0.05 (significant). The data presented are the average values of duplicated experiments, with the error bars showing the standard deviations.

A comparison between the results presented in Fig. 1 and 2 shows that the yields of extracted proteins from enzymatically treated cells were similar to those achieved by ultrasonication. However, when ultrasonication was not very effective, as in the case of Chlorella sp., enzymatic treatment was effective and showed better results.

The time‐course experiments showed increasing extracted proteins yields with prolonging the incubation time with the lysozyme. It was expected that a longer exposure time to the lytic enzyme would result in more disruption of the cell walls. Both enzymes performed well, with lysozyme generally performing better than cellulase, during the time‐course of the experiments. However, for Chlorella sp, the better performance of lysozyme was only at shorter treatment periods, and both enzymes performances were almost the same for the 16 h treatment. In addition, the extracted protein yields from cellulase treated cells of Chlorella sp. were nearly equal to the total proteins content determined using commercial lytic kit. This is in agreement with reported results, confirming the presence of a considerable amount of cellulose in cell wall of Chlorella sp. 23.

High‐pressure homogenization and alkaline treatments were tested to disrupt microalgae cell walls and enhance the extraction of proteins 24. The highest protein yield was achieved from Porphyridium cruentum microalgae, which has an actual protein content of 0.58 g/g dry weight. The extraction yields from alkaline treated and high‐pressure homogenized cells were 0.44 and 0.52 g/g dry weight, which correspond to 76 and 88% of the actual protein content 24. Other tested strains showed lower yields compared to the actual protein contents, ranging between 76 and 41%. In general, the extraction yields from high‐pressure treated cells were higher than those achieved using chemical treatment for all of the reported microalgae's strains. This work resulted in better yields of proteins extracted from the tested microalgae mass, with lysozyme treatment for 16 h (ranging from 79 to 97% of the actual protein content).

The protein contents in Chlorella sp. and Scenedesmus sp. found in this study were 0.72 and 0.78 g/g, respectively, which are higher than those reported in the literature 25, 26 for the same strains, 0.57 and 0.56 g/g, respectively. Although the strains could be from the same genus, their species might have been different. In addition, the higher protein contents found in this work could result from a higher accumulation of proteins, at the expense of the lipids, in the microalgae adapted to the high temperatures in the UAE region, where in summer it may reach as high as 50°C. The adaptation of the strains to the higher temperature in the environment can alter the metabolic pathway more towards the protein production. For example, Vasileva et al. 27 and Pancha et al. 28 quantified the lipid contents of Scenedesmus sp. to be around 0.30 and 0.20 g/g, respectively, whereas in our previous work 17, it was shown that the lipid contents of the same strain did not exceed 0.12 g/g in nitrogen rich medium. The inverse effect of temperature on the lipid contents, which in turn resulted in increasing protein contents, was also confirmed by Renaud et al. 29. A decrease of the lipid contents of C. vulgaris microalgae from 14.71 to 5.90% was also reported with the increase in temperature from 25 to 30°C 30. However, the same study reported an opposite effect of temperature on the lipid contents of N. oculata. It should be noted though that the effect of temperature referred to here is not the growth condition, but rather the adaptation of the strains to the higher temperature in the environment, which alters the metabolic pathway more towards the protein production. Yet another possibility to explain the increased protein content in the microalgae is the effect of the medium used. Vasileva et al. 27 showed that the protein content in Scenedesmus sp. changes with concentration of the growth medium and the type of nitrogen source it contains. The highest extracted protein of 0.43 g/g dry weight was observed in urea‐containing medium. A slightly higher protein content of 0.47 g/g was also reported by Pancha et al. 28 using the same strain grown in BG‐11 medium. This explain the lower protein contents reported in the works of Vasileva et al. 27 and Pancha et al. 28 compared to those reported in the literature for the same strain, which reached 0.57 g/g 25, 26.

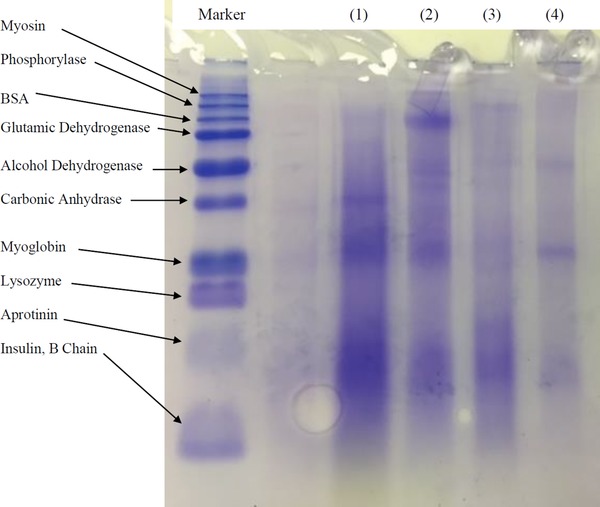

3.2. Proteins fractions and molecular weights

The extracted proteins by ultrasonication from the three selected strains, aforementioned in Section 3.1, namely Chlorella sp., Scenedesmus sp. and M.C. sp, were fractionated using HiTrap Q HP (Prepacked Q Superose High Performance strong ion exchange column), and the results are shown in Table 1. For these experiments, ultrasonication was chosen as a preferable extraction technique over enzymatic treatment to avoid the interference if the protein found in the enzymes. The results revealed that the proteins did not show a specific trend and considerable fractions eluted at all NaCl concentrations. This was also reflected in the molecular weights distribution of the extracted crude microalgae soluble proteins as shown in Fig. 3. The observed distributed bands suggest that the proteins extracted from Chlorella sp. have a range of different molecular weights. However, Chlamydomonas sp. and Scenedesmus sp. have slightly higher concentration of heavier molecular weights fractions. Table 1 displays two main fractions of proteins from M.C. sp. extract, one at low NaCl concentration and anther at medium concentration. This is reflected in the two clear bands shown in Fig. 3.

Table 1.

Protein fractions from Chlorella sp., Scenedesmus sp., M.C. sp. A. Braunii, and Pseudochlorococcum sp. using prepacked Q superose high performance strong ion exchange column

| NaCl concentration in the elution solution | Chlorella | Scenedesmus | M.C.Sp. | A. Braunii | Pseudochlorococcum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction 1 (0.1M) | 24.2 | 31.1 | 25.4 | 24.8 | 12.0 |

| Fraction 2 (0.2M) | 4.8 | 20.7 | 10.5 | 30.1 | 32.0 |

| Fraction 3 (0.3M) | 4.8 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 16.8 | 12.0 |

| Fraction 4 (0.4M) | 0.0 | 2.6 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 4.0 |

| Fraction 5 (0.5M) | 4.8 | 1.6 | 4.1 | 7.1 | 4.0 |

| Fraction 6 (0.6M) | 24.2 | 4.1 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 8.0 |

| Fraction 7 (0.7M) | 9.7 | 5.2 | 12.2 | 3.5 | 14.0 |

| Fraction 8 (0.8M) | 9.7 | 19.7 | 13.9 | 0.9 | 4.0 |

| Fraction 9 (0.9M) | 9.7 | 2.1 | 11.5 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Fraction 10 (1.0M) | 8.2 | 6.2 | 4.7 | 1.8 | 8.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Figure 3.

Molecular weight distribution of crude extracted proteins: (1) Chlamydomonas sp., (2) Chlorella sp., (3) Scenedesmus sp. and (4) M.C. sp.

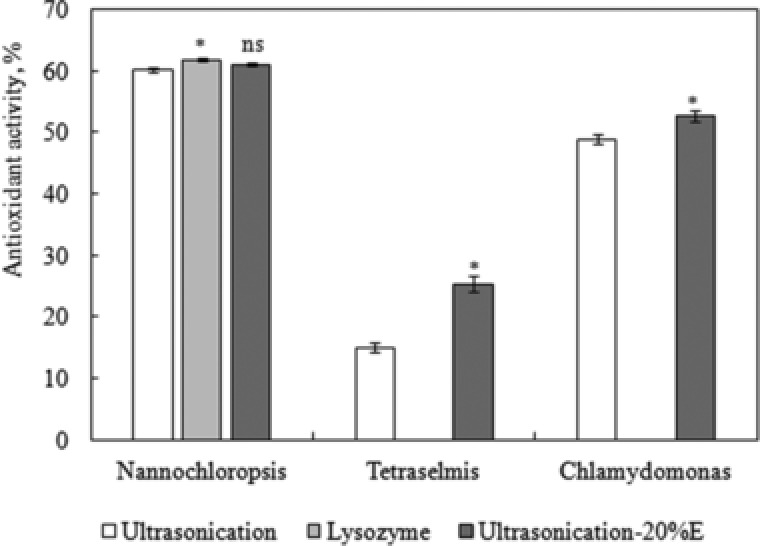

3.3. Antioxidant activity

Many previously reported evidences confirm a relationship between protein's antioxidant capacity and structural stress. Almost all forms of reactive oxygen species (ROS) oxidize methionine residues of proteins to a mixture of the R‐ and S‐isomers of methionine sulfoxide. It was proposed that the cyclic oxidation/reduction of methionine residues might serve as antioxidants to scavenge ROS, and also to facilitate the regulation of critical enzyme activities, through the methionine sulfoxide reductases, and catalyze the thioredoxin‐dependent reduction of the sulfoxides back to methionine in the organisms 31. It is therefore interesting to determine the antioxidant activities of the proteins extracted from microalgae. The antioxidant activity of proteins extracted from ultrasonicated strains, namely, Nannochloropsis sp., Tetraselmis sp. and Chlamydomonas sp has been determined in this work. The results in Fig. 4 show the activity of the extracts from the strains under investigation. Nannochloropsis sp. showed the highest activity of 60.2% (equivalent to 0.0079 mg Trolox mL−1), followed by Chlamydomonas sp. with 48.9% activity (equivalent to 0.0028 mg Trolox mL−1). The experiment was repeated using Nannochloropsis sp. (the strain that showed the highest activity) treated with lysozyme. As shown in Fig. 4, the antioxidant activity increased to 61.8% (equivalent to 0.0087 mg Trolox mL−1), which was due to the enhanced cell disruption with lysozyme. The t‐test results showed p < 0.05, which confirmed that the increase was not due to experimental randomness.

Figure 4.

Comparison between the antioxidant activities of the crude extracts of lysozyme treated and ultrasonicated biomass of different microalgae strains. *Comparison between Nannochloropsis treated with lysozyme and ultasonication: 0.01< p < 0.05 (significant). ns Comparison between Nannochloropsis treated with ultrasonication and ultrasonication E20: p > 0.05 (not significant). *Comparison between Chlamydomonas sp. and Tetraselmis sp. treated with ultrasonication and ultrasonication E20%: 0.01< p < 0.05 (significant). The data presented are the average values of duplicated experiments, with the error bars showing the standard deviations.

As mentioned earlier, phenolic have been reported to be one of the main sources of natural antioxidants and proved to be more potent antioxidants than Vitamin C and E and carotenoids 32. The phenolic have been reported to dissolve well in 20% ethanol–water mixture 7. Therefore, the experiment was repeated for the three strains with ultrasonication, but in 20% v/v ethanol–water mixture (referred to by E20%), instead of distilled water. The results in Fig. 4 show that the extract from Nannochloropsis sp. showed a slight increase in the antioxidant activity to reach 61.1% (equivalent to 0.0083 mg Trolox mL−1). The t‐test results showed p < 0.1, which suggests that the increase was not significant, and that the proteins, extracted in distilled water, have antioxidant activity similar to that of phenolic, extracted in E20%. The increase in the activity of the extracts from Chlamydomonas sp. cells were more evident, reaching 52.8% (equivalent to 0.0045 mg Trolox mL−1), respectively, with more significant t‐test results, p < 0.05.

3.4. Total phenolic contents

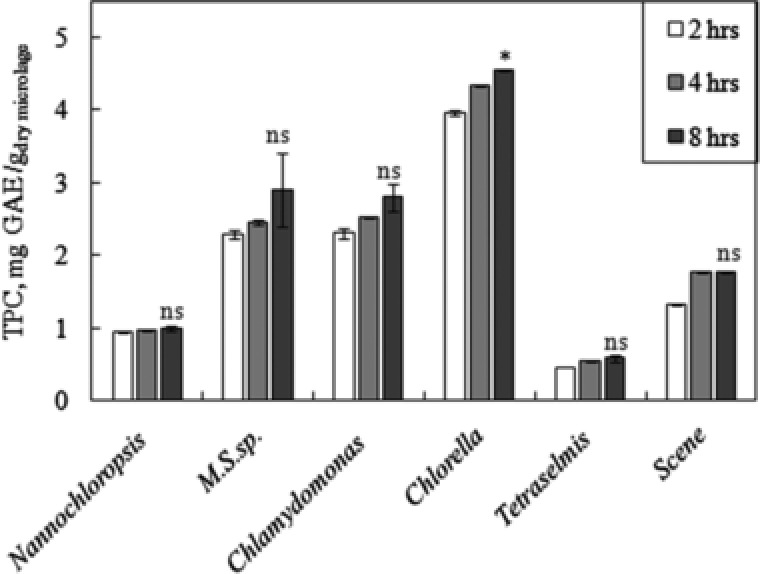

The phenolic contents in the crude protein extracts, from different microalgae strains treated with lysozyme for 2, 4 and 8 h, are shown in Fig. 5. It can be seen that the phenolic content increased during the time of incubation with the lytic enzyme, which was expected, as the longer exposure to the lytic enzyme results in more disruption of the cell walls. The differences in phenolics obtained after 4 and 8 h incubations were relatively small. The t‐test results showed that the differences were not significant, with p > 0.05. Except for Chlorella sp., which showed a significant difference with 0.01<p <0.05. Nevertheless, as shown in Fig. 5, this small p‐value was mainly due to the small difference between the two runs at the same time, which is shown in the small error bar. In addition, since lysozyme was used in this test, the rate of proteins extraction rate is expected to be fast, as shown in Fig. 2, unlike the use of cellulase. The crude extracts from Chlorella sp. showed the highest phenolic content. Generally, the extracts from freshwater microalgae strains contained higher phenolic contents compared to those from marine strains. Generally, the phenolic contents in crude proteins extracts were relatively small. This is mainly because the extraction was done in water, whereas phenolic compounds dissolve better in ethanol–water mixtures 7. This suggests that the high antioxidant activity of the crude proteins extracts is mainly due to the activity of the extracted proteins themselves. With Nannochloropsis sp, the antioxidant activity of the proteins extracts was close to that of the total phenols extracted using 20% ethanol, as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 5.

TPCs found in the crude extracts of lysozyme treated cells of different microalgae strains. *Comparison between phenolics extracted at 4 and 8 h for Chlorella sp.: 0.01< p < 0.05 (significant). ns Comparison between phenolics extracted at 4 and 8 h for all strains except Chlorella sp.: p > 0.05 (not significant). The data presented are the average values of duplicated experiments, with the error bars showing the standard deviations.

To determine the TPC in the microalgae, the experiment was repeated with 8 h treatment with lysozyme, but the phenolic were extracted using 20% (v/v ethanol‐water) mixture (referred to by E20%). Using this solvent, the amount of TPC values increased drastically. The TPC values of Chlorella sp. increased from 4.6 ± 0.01 mg GAE gdry microalgae −1 using water to 17.0 ± 0.05 mg GAE gdry microalgae −1 using E20%. For M.C. sp., Chlamydomonas sp. and Scenedesmus sp., the increase was more significant, from 2.9 ± 0.03, 2.8, ± 0.02 and 1.8 ± 0.01 mg/g to 25.6 ± 0.01, 16.9, ± 0.05 and 12.8 ± 0.01 mg GAE gdry microalgae −1, respectively. The results obtained by E20% solvent system were in agreement with those found by Turkmen et al. 7 on phenolic extracted from tea leaves. For example, it was found that the TPC extracted from black tea using water was 33.3 mg GAE gdry microalgae −1, which increased to 130.6 mg GAE gdry microalgae −1 using E20% solution. It is worth mentioning here that increasing the ethanol percentage resulted in reducing the amount of extracted phenolic. Although the phenolic contents in the crude proteins extracts were low, those extracts displayed high antioxidant activity, presumably due to the activity of the extracted proteins themselves.

3.5. Pigments extraction

It was shown that cell disruption, achieved through grinding, homogenization, ultrasound or sonication, significantly improves the effectiveness of chlorophyll extraction using organic solvents 33, 34, 35. On the other hand, the use of lysozyme was shown to enhance the lipid extraction from microalgae, due to the enhanced cell wall disruption 17.” In this study, the enhancement of pigments extraction by enzyme pre‐treatment using lysozyme was assessed. Table 2 shows the pigments extracted from five microalgae strains, namely, Chlorella sp., Scenedesmus sp., M.C. sp., Chlamydomonas sp. and Nannochloropsis sp. for the lysozyme treated and untreated biomasses. The selected strains were marine and freshwater to confirm the applicability of both to the enzymatic treatment. It was found that lysozyme pre‐treatment significantly increased the amount of extracted pigments. It is well known that cell wall of Chlorella sp. is sensitive to lysozyme that degrade polymers containing N‐acetylglucosamine 36. In addition to cell disruption, the type of solvent used affects the extraction efficiency. It was reported that 90% acetone is a less effective solvent than methanol 37. This explains the low amounts of extracted pigments from untreated samples using 80% acetone in this work. However, the use methanol as an extraction solvent is not preferred because it results in an unstable solution and leads to the formation of chlorophyll a degradation products 38. Acetone solution on the other hand strongly inhibited the formation. This justifies the need for effective cell disruption, using lysozyme, which significantly enhanced the extraction.

Table 2.

Comparison between the amounts of extracted pigments from lysozyme treated and untreated biomass of Chlorella sp., Scenedesmus sp., M.C. sp. Chlamydomonas sp., and Nannochloropsis sp

| Strain | Chlorophyll a (mg/g) | Chlorophyll b (mg/g) | Total carotenoids (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorella (treated) | 16.02 ± 0.39 | 4.59 ± 0.10 | 5.22 ± 0.04 |

| Chlorella (untreated) | 0.4 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.00 |

| Scenedesmus (treated) | 8.24 ± 0.10 | 1.59 ± 0.15 | 1.84 ± 0.08 |

| Scenedesmus (untreated) | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.17± 0.00 | 0.07 ± 0.00 |

| M.C. Sp. (treated) | 9.77 ± 0.11 | 2.72 ± 0.26 | 3.19 ± 0.17 |

| M.C. Sp. (untreated) | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.41 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.00 |

| Chlamydomonas (treated) | 1.39 ± 0.06 | 0.89 ± 0.21 | 0.60 ± 0.30 |

| Chlamydomonas (untreated) | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.00 |

| Nannochloropsis (treated) | 14.38 ± 0.10 | 3.54 ± 0.51 | 3.8 ± 0.12 |

| Nannochloropsis (untreated) | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.00 |

The highest extracted pigment content was from the freshwater strain, Chlorella sp. It was interesting to notice that the pigment content of the marine strain, Nannochloropsis sp., was comparable to that of Chlorella, and higher than the other three freshwater strains. Macias‐Sanchez et al. 37 tested the extraction of chlorophyll a and total carotenoids from freeze dried Synechococcus sp. using supercritical CO2 and compared their results to methanol extraction. The pigments were extracted at 500 bars and 60°C, and the yield was only 0.72 mg/g dry weight. The yield was lower than that achieved using methanol on ultrasonicated biomass, which was 4.1 mg/g dry weight. The highest yield of the pigments was extracted using acetone solution on lysozyme treated biomass, in the range of 8.2–16.0 mg/g. The extracted yield of total carotenoids using supercritical CO2 at the optimum conditions was similar to the extracted quantity achieved using methanol, which was 1.3 mg/g. However, the treatment with lysozyme followed by extraction with acetone achieved yields in the range of 3.2–5.2 mg/g.

From all results, Chlorella sp. was identified as the best candidate strain for protein and pigments extraction. The protein content of this strain was found to be 73%, determined using the commercial lytic kit. Almost all the proteins were extracted with a yield of 70% after treatment with lysozyme for 16 h. The crude extract from this strain showed the highest TPC of 4.5% after treatment for 8 h with lysozyme, compared to other tested strains. The extracted pigments were also the highest from this strain. The treatment for 12 h with lysozyme achieved extraction of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total carotenoids contents of 16.02, 4.59 and 5.22 mg/g, respectively.

4. Concluding remarks

Different microalgae strains were cultivated and crude proteins were successfully extracted using enzymatic pre‐treatment. The yields of extracted proteins from enzymatically treated cells were similar to those achieved by conventional ultrasonication technique. The enzymatic process is more preferable, as it has the advantage of operating at milder conditions and lower energy requirements, compared to untriasonication process. In addition, with Chlorella sp., enzymatic treatment showed a superior performance over the ultrasonication process. Low phenolic compounds were co‐extracted with the proteins that showed comparable antioxidant activity compared to total phenolic compounds extracted using 20% ethanol solution. It was also found that lysozyme pre‐treatment, along with better cell disruption, significantly increased the amount of extracted pigments from the microalgae. These extracted active natural compounds are of great interest due to their possible therapeutic applications.

Practical application.

Lytic enzymes, lysozyme and laccase, have been used to disrupt the cell walls of selected microalgae strains and enhance extraction of proteins and pigments. In addition, the use of enzymes has the advantage of operating at mild conditions and low energy requirements. The yields of extracted proteins from enzymatically treated cells were similar to those achieved by conventional ultrasonication technique. However, when ultrasonication was not very effective, as in the case of Chlorella sp. (extraction yield not exceeding 0.4 mg per mg dry cell), enzymatic treatment was effective and showed better extraction (0.7 mg per mg dry cell). It was also found that by lysozyme pre‐treatment, along with the better cell disruption, a significant increase in the amount of extracted pigments from the microalgae was achieved. These extracted active natural compounds are of great interest due to their possible therapeutic applications.

Nomenclature

| AA% | [–] | Percentage of the antioxidant activity |

| Ai | [–] | Absorption at different wavelengths |

| Ca | [μg/mL] | Chlorophyll a concentration |

| Cb | [μg/mL] | Chlorophyll b concentration |

| Ct | [μg/mL] | Total carotenoids concentration |

| Indices | ||

| i | [nm] | Wavelength |

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support provided by Zayed Center for Health Sciences (Fund# 31R019) and Prof. Koroush Salihi from the New York University Abu Dhabi, for providing samples of Chlamydomonas sp. used in this work.

5 References

- 1. Amaro, H. M. , Barros, R. , Guedes, A. C. , Sousa‐Pinto, I. et al., Microalgal compounds modulate carcinogenesis in the gastrointestinal tract. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Foley, P. M. , Beach, E. S. , Zimmerman, J. B. , Algae as a source of renewable chemicals: Opportunities and challenges. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Afify, A. M. , El‐Beltag, H. S. , Fayed, S. A. , Shalaby, E. A. , Acaricidal activity of different extracts from Syzygium cumini L. Skeels (Pomposia) against Tetranychus urticae Koch. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2011, 13, 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shanab, S. M. , Mostafa, S. S. , Shalaby, E. A. , Mahmoud, G. I. , Aqueous extracts of microalgae exhibit antioxidant and anticancer activities. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, 608–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guedes, A. C. , Amaro, H. M. , Malcata, F. X. , Microalgae as sources of high added‐value compounds‐a brief review of recent work. Biotechnol. Prog. 2011, 27, 597–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blasa, M. , Gennari, L. , Angelino, D. , Ninfali, P. , Fruit and vegetable antioxidants in health, in: Watson R., Preedy V. (Eds.), Bioactive Foods in Promoting Health. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turkmen, N. , Sari, F. , Velioglu, Y. S. Effects of extraction solvents on concentration and antioxidant activity of black and black mate tea polyphenols determined by ferrous tartrate and Folin–Ciocalteu methods. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 835–841. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Armstrong, G. A. , Genetics of eubacterial carotenoid biosynthesis, a colourful tale. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 51, 629–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wellburn, R. , The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometer of different resolutions. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee, J. Y. , Yoo, C. , Jun, S. Y. , Ahn, C. Y. et al., Comparison of several methods for effective lipid extraction from microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, S75–S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gerde, J. A. , Montalbo‐Lomboy, M. , Yao, L. , Grewell, D. et al., Evaluation of microalga cell disruption by ultrasonic treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 125, 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zheng, H. , Yin, J. , Gao, Z. , Huang, H. et al., Disruption of Chlorella vulgaris cells for the release of biodiesel‐producing lipids: A comparison of grinding, ultrasonication, bead milling, enzymatic lytic, and microwaves. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2011, 164, 1215–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mendes‐Pinto, M. M. , Raposo, M. F. J. , Bowen, J. , Young, A. J. et al., Evaluation of different cell disruption processes on encysted cells of Haematococcus pluvialis: Effects on astaxanthin recovery and implications for bio‐availability. J. Appl. Phycol. 2001, 13, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jubeau, S. , Marchal, L. , Pruvost, J. , Jaouen, P. et al., High pressure disruption: A two‐step treatment for selective extraction of intracellular components from the microalga Porphyridium cruentum . J. Appl. Phycol. 2012, 25, 983–989. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sari, Y. W. , Bruins, M. E. , Sanders, J. P. M. , Enzyme assisted protein extraction from rapeseed, soybean, and microalgae meals. Ind. Crop Prod. 2013, 43, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee, A. K. , Lewis, D. M. , Ashman, P. , Disruption of microalgal cells for the extraction of lipids for biofuels: Processes and specific energy requirements. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 46, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Taher, H. , Al‐Zuhair, S. , AlMarzoqui, A. , Haik, Y. et al., Effective extraction of microalgae lipids from wet biomass for biodiesel production. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 66, 159–167 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stoscheck, C. M. , Quantitation of protein. Method Enzymol. 1990, 182, 50–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shen, Q. , Zhang, B. , Xu, R. , Wang, Y. et al., Antioxidant activity in vitro of selenium‐contained protein from the se‐enriched. Bifodoba. anim. 01 . Anaerobe 2010, 16, 380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liao, H. , Dong, W. , Shi, X. , Liu, H. et al., Analysis and comparison of the active components and antioxidant activities of extracts from Abelmo. escule. L . Pharm. Mag. 2012, 8, 156–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singleton, V. L. , Rossi, J. A. , Colorimetry of total phenolic with phosphomolybdic‐ phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ursu, A. V. , Marcati, A. , Sayd, T. , Sante‐Lhoutellier, V. et al., Extraction, fractionation and functional properties of proteins from the microalgae Chlor. vulgaris . Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 157, 134–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meindl, L. , Cell wall‐lytic activity in Chlorella fusca . Planta 1984, 160, 357–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Safi, C. , Charton, M. , Ursu, V. A. , Laroche, C. et al., Release of hydro‐soluble microalgal proteins using mechanical and chemical treatments. Algal Res. 2014, 3, 55–60 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Becker, E. W. , Micro‐algae as a source of protein. Biotechnol. Adv. 2007, 25, 207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Al hattab, M. A. , Ghaly, A. E. , Microalgae oil extraction pre‐treatment methods: Critical review and comparative analysis. J. Renew. Energy Appl. 2015, 5, 1–26 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vasileva, I. A. , Marinova, G. V. , Gigova, L. G. , Effect of nitrogen source on the growth and biochemical composition of a new Bulgarian isolate of Scenedesmus sp . J. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2015, SE/ONLINE, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pancha, I. , Choksh, K. , George, B. , Ghosh, T. et al., Nitrogen stress triggered biochemical and morphological changes in the microalgae Scenedesmus sp. CCNM 1077. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 156, 146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Renaud, S. M. , Zhou, H. C. , Parry, D. L. , Thinh, L. V. et al., Effect of temperature on the growth, total lipid content and fatty acid composition of recently isolated tropical microalgae Isochrysis sp., Nitzschia closterium, Nitzschia paleacea, and commercial species Isochrysis sp. (clone T.ISO). J. Appl. Phycol. 1995, 7, 595–602 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Converti, A. , Casazza, A. A. , Ortiz, E. Y. , Perego, P. et al., Effect of temperature and nitrogen concentration on the growth and lipid content of Nannochloropsis oculata and Chlorella vulgarisfor biodiesel production. Chem. Eng. Proc. Proc. Intensification 2009, 48, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stadtman, E. R. , Moskovitz, J. , Berlett, B. S. , Levine, R. L. , Cyclic oxidation and reduction of protein methionine residues is an important antioxidant mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002, 3–9, 234–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dai, J. , Mumper, R. J. , Plant phenolic: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Macías‐Sánchez, M. D. , Mantell, C. , Rodríguez, M. , Martínez de la Ossa, E. et al., Comparison of supercritical fluid and ultrasound‐assisted extraction of carotenoids and chlorophyll a from Dunaliella salina . Talanta 2009, 77, 948–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sartory, D. P. , Grobbelaar, J. U. , Extraction of chlorophyll a from freshwater phytoplankton for spectrophotometric analysis. Hydrobiologia 1984, 114, 177–187. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Simon, D. , Helliwell, S. , Extraction and quantification of chlorophyll a from freshwater green algae. Water Res. 1998, 32, 2220–2223. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gerken, H. G. , Donohoe, B. , Knoshaug, E. P. , Enzymatic cell wall degradation of Chlorella vulgaris and other microalgae for biofuels production. Planta 2013, 237, 239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Macías‐Sánchez, M. D. , Mantell, C. , Rodríguez, M. , Martínez de la Ossa, E. et al., Supercritical fluid extraction of carotenoids and chlorophyll a from Synechococcus sp . J. Supercrit. Fluid 2007, 39, 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mantoura, R. F. C. , Llewellyn, C. A. , The rapid determination of algal chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments and their breakdown products in natural waters by reverse‐phase highperformance liquid chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta 1983, 151, 297–314. [Google Scholar]