Abstract

Downstream processing remains one of the biggest challenges in manufacturing of biologicals and vaccines. This work focuses on a Design of Experiments approach to understand factors influencing the performance of sulfated cellulose membrane adsorbers for the chromatographic purification of a cell culture‐derived H1N1 influenza virus strain (A/Puerto Rico/8/34). Membranes with a medium ligand density together with low conductivity and a high virus titer in the feed stream resulted in optimum virus yields and low protein and DNA content in the product fraction. Flow rate and salt concentration in the buffer used for elution were of secondary importance while membrane permeability had no significant impact on separation performance. A virus loss of 2.1% in the flow through, a yield of 57.4% together with a contamination level of 5.1 pgDNA HAU−1 and 1.2 ngprot HAU−1 were experimentally confirmed for the optimal operating point predicted. The critical process parameters identified and their optimal settings should support the optimization of sulfated cellulose membrane adsorbers based purification trains for other influenza virus strains, streamlining cell culture‐derived vaccine manufacturing.

Keywords: Design of Experiments, Downstream processing, Influenza A virus purification, Membrane adsorption chromatography, Sulfated cellulose

Abbreviations

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- DNAprod

DNA content in the product fraction

- DoE

Design of Experiments

- Feedcond

conductivity of the virus feed stream

- FeedHAU

virus titer in the feed stream

- FTvirus

virus loss in the flow through

- LD

ligand density

- MDCK

Madin‐Darbin Canine Kidney (cell line)

- Protprod

total protein content in the product fraction.

- Q

flow rate

- SCMA

sulfated cellulose membrane adsorbers

- SV

total system volume

1. Introduction

The purification of cell culture‐derived virus particles is still a challenge in influenza vaccine manufacturing. It should be efficient, economically viable, robust regarding the seasonal update of vaccine composition, and reliably result in a product quality accepted by regulation agencies. Furthermore, the downstream processing (DSP) should be scalable to cope with increasing market demands for prevention of seasonal epidemics (requiring trivalent or tetravalent formulations) as well as enable a fast response in cases of pandemics. Finally, advances in upstream virus production techniques, like the use of different cell culture systems 1, 2, 3 and high cell density culture systems 4 present new challenges in DSP of influenza viruses that need to be addressed 5.

Several unit operations have been described for the purification of virus particles 3, 5, 6. Density gradient ultracentrifugation (e.g. using sucrose) is used extensively for concentration and purification of egg and cell culture‐derived virus particles. Given its strain independency, this unit operation is also used at industrial level 3. As an alternative, several DSP schemes include one or more chromatographic separation steps 3, 5. These are easier to scale‐up and have lower investment and operating costs 6. Several chromatography techniques were reported for the purification of influenza virus, as reviewed by Wolff, M. and Reichl, U. 3. One of them explores the use of pseudo‐affinity chromatography based on sulfated carbohydrate matrices for binding of influenza virus particles 5. Heparin is a highly sulfated glycosaminoglycan 7, which interacts with viral proteins, from influenza virus but also from herpes, flavi, adeno‐associated and immunodeficiency type 1 viruses and others 5. Alternatively, simple and cost‐effective carbohydrates that mimic the properties of heparin should be considered. Carbohydrates constitute the base of various chromatographic supports, e.g. as cellulose or dextran. These can be chemically modified to include sulfate groups (‐OSO3 −) as ligands 8. Such materials are currently commercially available as bead‐based matrices, namely, Cellufine™ sulfate (JNC Corporation) and Capto™ DeVirs (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Their use for purification of influenza virus particles is covered by various publications 3, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14. The same surface chemistry can also be applied to cellulose membrane adsorbers 13, 14 to improve productivity and to overcome problems related to packed bed columns. First, membrane adsorbers can be operated at higher flow rates, given their higher pressure limits. Second, the total available binding surface effectively used is larger, as the surface of membranes is more accessible for binding of large particles, like influenza viruses (∼100 nm 15), which are excluded from the internal pore surface of beads 6.

Sulfated cellulose membranes adsorbers (SCMA) can be used as a capture step for purification of influenza virus particles, as shown first by Opitz et al. 10, and in a follow‐up study of Weigel et al. 12. However, the influence of process conditions including the choice of membrane properties has not been well characterized until now. In its review on downstream processing of viral vectors and vaccines, Morenweiser 6 highlighted the need to systematically investigate and optimize chromatographic processes to improve efficiency and robustness. In a broader context, Muthukumar, S. and Rathore, A. S. 16 pointed out the importance of understanding and optimizing process parameters involved in the switch from packed bed to membrane chromatography.

Design of Experiments (DoE) is a valuable tool for both in academia and industry. The advantages of its application in the production of biopharmaceuticals are widely covered 17, 18, 19. Although less intuitive than the ‘changing one separate factor at a time’ approach, the application of a DoE strategy can significantly increase the amount and the (statistical) meaning of the information retrieved when screening or optimizing experimental factors. Simultaneously, it can reduce the number of experiments required, saving time and resources 17. Several applications describe the use of DoE for factor screening and optimization of chromatographic processes 16, 20, 21, 22, including membrane chromatography 16. Ji et al. 20 investigated the influence of loading pH, NaCl concentration, volume and flow rate in the performance of a packed‐bed column in flow through mode (Capto™ Adhere) for the purification of a Streptococcus pneumonia capsular polysaccharide for vaccine production. The study concluded that the NaCl concentration of the loading buffer had the largest effect on the separation. Furthermore, Afonso et al. 21, optimized the purification of specific pre‐microRNA, a potential Alzheimer's therapeutic agent, via a newly established O‐phospho‐L‐tyrosine affinity chromatography process. They used a Box‐Behnken design to determine the temperature, binding and elution salt concentrations resulting in optimal product recovery and purity. Given that the goal was an optimization, all three factors were highly relevant. Almeida et al. 22 applied a Composite Central Face design to improve the recovery of plasmid DNA, from an arginine monolith. They optimized the pH‐value, the NaCl concentration of the binding and washing buffer, and showed that the pH‐value was a critical parameter for the success of the purification. Regarding membrane chromatography, Muthukumar, S. and Rathore, A. S. 16 reported the use and validation of DoE as a platform for process development in miniaturized systems (96‐well plates, single layer, 7 μL total membrane bed volume) compared to laboratory scale (16 layers stacked membranes, 25 mm diameter, 0.86 mL total membrane bed volume). The two case‐studies presented by the authors are simple examples of how this platform can be applied in bind‐elute and in flow through mode, with traditional cation and anion exchangers. In both examples, the influence of pH‐value and NaCl concentration of the binding buffer for the recovery of a glycoprotein expressed in Escherichia coli was investigated. The authors obtained similar results at both investigated scales, which underlines the advantages of using DoE.

This work identifies factors that are relevant for SCMA‐based purification of cell culture‐derived influenza A virus. Furthermore, it investigates to what extent virus yield as well as protein and host cell DNA content can be optimized using a DoE approach. In the first part, six different factors (inputs) were screened and their influence evaluated with four different responses (outputs), reflecting process performance. In the second part, the optimal operating point to obtain high virus particle yields together with low contamination levels was determined and confirmed experimentally.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Virus production and primary purification

MDCK.SUS2 suspension cells were cultivated according to Lohr et al. 1 (37°C, 5% CO2, 130 rpm; Multitron orbital incubator, Infors HT, Bottmingen, Switzerland) in 600 mL working volume shakers (VWR International GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) using a chemically defined medium (Smif8, Gibco, by contact through K. Scharfenberg, FH Oldenburg/Ostfriesland/Wilhelmshaven, Germany) supplemented with 4 mM L‐glutamine and 4 mM pyruvate (#G3126 and #P0564, Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The infection with H1N1 influenza virus A/PuertoRico/8/34 (Robert Koch‐Institute, Berlin, Germany) adapted to MDCK.SUS2 suspension cells was done at 2.5 × 106 cells/mL at a multiplicity of infection of 1 × 10−5, with 50% medium volume exchange at time of infection, and the addition of 5000 U trypsin (#27250‐018, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). After 72 h, the culture broth was harvested and clarified with a series of Sartopure® PP3 filters (5 and 0.65 μm, #5055342P7–FF–A, #5051305P4–SS–B, Sartorius Stedim Biotech GmbH, Göttingen, Germany). The clarified virus material was then chemically inactivated by addition of β‐propiolactone (#33672.01, SERVA Electrophoresis GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) to a final concentration of 8 mM and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Afterwards, a secondary clarification was done using a 0.45 μm Sartopure® PP3 filter (#5051306P4–SS–B, Sartorius Stedim Biotech GmbH, Göttingen, Germany), and the clarified virus material concentrated by tangential flow filtration using a Sartocon® slice 200 cassette containing a 750 kDa regenerated cellulose membrane prototype (Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Göttingen, Germany) connected to an ÄKTAcrossflow system (UNICORN™ 5.1 software; GE Healthcare Amersham Biosciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Finally, the concentrated virus material was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until further use.

2.2. Membrane production

Sulfated reinforced cross‐linked regenerated cellulose membranes were produced as described by Villain et al. 14. The different combinations of membrane‐related parameters addressed in the experimental design (see Table 1 in 2.3), namely ligand density and membrane permeability, were achieved by varying the sulfation and cellulose cross‐linking processes 14. The ligand density of each prototype tested was determined by titration. Briefly, the membrane is equilibrated with a 1M HCl solution and then washed with purified water. Therefore, there are only H+ ions in the vicinities of the sulfate ligands. Afterward, a NaOH solution (10 mM) is gradually added and the H+ ions are replaced with Na+. By monitoring the conductivity in the membrane outlet, it is possible to calculate the ligand density by determining the area under the conductivity curve until complete breakthrough of the Na+ ions (maximum conductivity) 14. The membrane permeability was measured with 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.0. The membranes were packed in devices with 6 layers of 6.7 mm in diameter disks, for a total bed volume of 0.056 mL and a total surface area of 2.1 cm2.

Table 1.

Experimental factors and levels used for the investigation of SCMA for purifying cell culture‐derived influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 using a DoE approach

| Factor | Abbreviation | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Center | High | ||

| Ligand density (μmol cm−1) | LD | 14 | 19.5 | 25 |

| Membrane permeability (mL (min bar cm2)−1) | Lp | 75 | 97.5 | 120 |

| Flow rate (mL min−1) | Q | 0.112 | 0.336 | 0.560 |

| [NaCl] in the step elution (mM) | [NaCl] | 200 | 1100 | 2000 |

| Conductivity of the feed stream (mS cm−1) | Feedcond | 4.0 | 6.5 | 9.0 |

| Virus titer in the feed stream (logHAU) | FeedHAU | 3.0 | 3.7 | 4.0 |

2.3. Experimental design

A Rechtschaffner design with resolution V was chosen to generate the experimental matrix using MODDE® Pro 11 (Sartorius Stedim Data Analytics, Malmö, Sweden). A total of six factors (inputs), membrane or process‐related, were screened for their influence on the separation performance of the SCMA. These factors were: ligand density (μmol cm−2), membrane permeability (mL (min bar cm2)−1), flow rate (mL min−1), NaCl concentration in the elution buffer (mM), conductivity (mS cm−1) of the feed conditioning buffer, and virus titer (logHAU, see Section 2.6.1). Four responses (outputs) were considered: virus loss in the flow through (FTvirus as % of the total amount of virus loaded), process yield (as % of the total amount of virus loaded found in the first elution step), and the content of DNA as well as the total protein content in the product fraction (DNAprod and Protprod as pgDNA HAU−1 and ngprot HAU−1, respectively, normalized to the virus titer of the same fraction).

The two‐level design space for the investigated factors (Table 1) was based on: scouting experiments performed regarding virus losses in the flow through for different salt concentrations of the feed conditioning buffer (data not shown); the recommended flow rate range for the prototypes (24 to 119 cm h−1); expected virus titers in the feed stream; as well as ligand density and membrane permeability of the SCMA prototypes investigated. The design matrix comprised 25 runs including three replicates of the center point performed in randomized order (Table 2). Furthermore, three additional runs were performed to complement the design matrix.

Table 2.

Rechtschaffner Res V design matrix implemented to investigate the influence of membrane‐related factors (membrane ligand density (LD) and membrane permeability (Lp)) and process‐related factors (conductivity of the feed material (Feedcond), virus titer in the feed material (FeedHAU), flow rate (Q), and salt concentration in the elution buffer ([NaCl]) on four responses (virus loss in the flow through (FTvirus), yield, DNA and total protein content in the product fraction (DNAprod and Protprod, respectively)). Center points are marked with a star (*)

| Run no. | Factors | Responses | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD (μmol cm−²) | Lp (mL (min bar cm²)−1) | Feedcond (mS cm−1) | FeedHAU (logHAU) | Q (mL min−1) | [NaCl] (mM) | FTvirus (%) | Yield (%) | DNAprod (pgDNA HAU−1) | Protprod (ngprot/HAU−1) | |

| 1 | 13.9 | 96 | 5.3 | 3.2 | 0.112 | 200 | 12.6 | 46.8 | 4.8 | 1.5 |

| 2 | 14.4 | 116 | 14.8 | 4.3 | 0.560 | 2000 | 49.6 | 7.8 | 20.7 | 2.3 |

| 3 | 25.6 | 78 | 10.7 | 4.2 | 0.560 | 2000 | 22.4 | 45.6 | 8.1 | 1.5 |

| 4 | 26.3 | 110 | 5.6 | 4.1 | 0.560 | 2000 | 5.7 | 73.3 | 5.7 | 1.4 |

| 5 | 26.3 | 110 | 9.6 | 4.2 | 0.112 | 2000 | 12.7 | 52.6 | 7.0 | 1.8 |

| 6 | 26.3 | 110 | 9.2 | 4.4 | 0.560 | 200 | 6.4 | 37.1 | 6.8 | 1.6 |

| 7 | 26.3 | 110 | 9.5 | 3.2 | 0.560 | 2000 | 26.9 | 49.6 | 4.7 | 1.7 |

| 8 | 26.3 | 110 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 0.112 | 200 | 6.8 | 45.6 | 5.6 | 1.7 |

| 9 | 25.6 | 78 | 9.8 | 3.1 | 0.112 | 200 | 29.3 | 37.0 | 5.2 | 1.6 |

| 10 | 25.6 | 78 | 4.6 | 3.3 | 0.560 | 200 | 14.9 | 37.3 | 16.1 | 1.0 |

| 11 | 25.6 | 78 | 5.3 | 3.2 | 0.112 | 2000 | 10.2 | 51.0 | 4.5 | 1.8 |

| 12 | 25.6 | 78 | 20.8 | 4.3 | 0.112 | 200 | 55.9 | 5.0 | 19.0 | 1.8 |

| 13 | 14.4 | 116 | 11.1 | 3.2 | 0.112 | 200 | 43.1 | 40.8 | 2.7 | 1.3 |

| 14 | 14.4 | 116 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 0.560 | 200 | 17.3 | 48.9 | 4.2 | 1.2 |

| 15 | 14.4 | 116 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 0.112 | 2000 | 12.3 | 55.2 | 5.0 | 1.4 |

| 16 | 14.4 | 116 | 9.2 | 4.3 | 0.112 | 200 | 8.9 | 41.3 | 5.6 | 1.3 |

| 17 | 13.9 | 96 | 9.4 | 3.1 | 0.560 | 200 | 35.6 | 57.6 | 3.0 | 1.3 |

| 18 | 13.9 | 96 | 10.0 | 3.3 | 0.112 | 2000 | 54.9 | 37.4 | 3.7 | 1.3 |

| 19 | 13.9 | 96 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 0.112 | 200 | 11.1 | 35.9 | 8.6 | 1.6 |

| 20 | 13.9 | 96 | 4.8 | 3.3 | 0.560 | 2000 | 4.3 | 47.0 | 3.5 | 1.0 |

| 21 | 13.9 | 96 | 5.1 | 4.2 | 0.560 | 200 | 13.5 | 50.1 | 4.9 | 1.3 |

| 22 | 13.9 | 96 | 5.2 | 4.3 | 0.112 | 2000 | 8.9 | 53.9 | 12.2 | 1.3 |

| 23* | 20.0 | 106 | 7.2 | 4.0 | 0.336 | 1100 | 5.5 | 46.3 | 9.2 | 1.5 |

| 24* | 20.0 | 106 | 7.3 | 3.9 | 0.336 | 1100 | 7.8 | 52.5 | 5.6 | 1.6 |

| 25* | 20.0 | 106 | 7.7 | 3.9 | 0.336 | 1100 | 3.8 | 67.8 | 5.1 | 1.3 |

| 26 | 26.3 | 110 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 0.560 | 2000 | 4.4 | 49.4 | 4.9 | 1.5 |

| 27 | 13.9 | 96 | 4.9 | 3.3 | 0.560 | 200 | 16.5 | 42.0 | 3.5 | 0.3a |

| 28* | 20.0 | 106 | 6.9 | 4.0 | 0.336 | 1100 | 1.7 | 60.0 | 11.0 | 1.5 |

Outlier, not considered in the model.

The same software was used for data fitting, using partial least squares regression (PLS) 23. All coefficients were scaled, centered and normalized to the variance of each response 23, 24. Except for the protein content, all responses were log10 transformed to improve the regression model and the reliability of predictions. The general second order polynomial equation that describes each response Y as a function of each factor X and all factor interactions is given by Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where are the calculated regression coefficients, n the total number of factors, and j all other factors except i.

2.4. Optimization of the purification process and model validation

Based on the data obtained from the experiments performed (Table 2), optimal settings of factors were identified using the Optimizer tool of the DoE software. The criteria were defined, within the Predictor’s range, to maximize virus yield, and to minimize losses in the flow through and both DNA and total protein content in the product fraction. The resulting ‘robust set point’ was chosen and experimentally verified with technical replicates (n = 3).

2.5. Chromatographic separation

2‐Amino‐2‐(hydroxymethyl)propane‐1,3‐diol (Tris) (Pufferan® ≥99.9%, #5429.2), hydrochloric acid (37%, ROTIPURAN®, #4625.2), and sodium chloride (Ph. Eur. ≥99%, #P029.3) were purchased from Carl Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany) and used for formulation of the buffers required for sample preparation and chromatographic separation. All buffers were filtered through a 0.2 μm PES bottle top membrane filter (#514‐0340, Radnor, PA, USA) and degassed.

For each run, the inactivated and concentrated virus material was thawed at room temperature and individually dialyzed (14 kDa Membra‐Cel™, #0653.1, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), overnight at 4°C, against a 10 mM Tris/HCl and different NaCl concentrations for adjustment to the conductivity required (see Table 2). Sodium azide (p.a. ≥ 99.0%, #71290, Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to prevent microbial growth (0.05% w/v in dialysis buffer). Afterwards, the virus titer in the feed stream was adjusted to the required value (see Table 2) by dilution with the same buffer used for dialysis. Finally, the samples were pre‐filtered with 0.45 μm single‐use cellulose acetate syringe filters (surfactant‐free, #16555———‐K, Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Göttingen, Germany).

The chromatographic separations were performed using an ÄKTA pure 25 system (UNICORN™ 6.3 software, GE Healthcare Bio‐Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) and monitored in‐line via UV‐signal (at 280 nm) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) detection (NICOMP™ 380 at 633 nm wavelength, Particle Sizing Systems, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). The duration of each chromatographic step was defined based on the total system volume (SV ∼ 0.5 mL) as this volume was much larger than the membrane volume. The membrane devices were first equilibrated (16 SV) with 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4 with the conductivity required for each run (Table 2). After loading of the virus material (in total ∼1.5 × 105 HAU using a variable volume according to the required dilution for each run, Table 2), the SCMA was washed (13 SV) with the same buffer used for equilibration. Finally, the elution was performed in two steps (6.5 SV each). The first elution step was done with 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4 containing a NaCl concentration according to the design matrix (Table 2). The second elution step was always performed with 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4 containing 2 M NaCl. Each experimental run was performed once with a new membrane device.

For the validation of the ‘robust set point’, the runs were performed in an analog manner according to the predicted factor values (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors and responses for the robust set point predicted by Monte Carlo simulation (resolution 32, 10 000 simulations per point, 95% confidence level. The responses obtained confirm the validity of the selected model. Responses as mean ± standard deviation of 3 technical replicates

| Factor | Predicted | Implemented |

|---|---|---|

| LD (μmol cm−2) | 20.6 ± 1.5 | 20.0 |

| Lp (mL (min.bar.cm2) −1) | ‐ | 106 |

| Q (mL min−1) | 0.375 ± 0.060 | 0.380 |

| [NaCl] (mM) | 560 ± 197 | 560 |

| Feedcond (mS cm−1) | 4.67 ± 0.43 | 4.7 |

| FeedHAU (logHAU) | 3.95 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.01 |

| Response | Predicted | Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| FTvirus (%) | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 1.5 |

| Yield (%) | 58.2 ± 3.3 | 57.4 ± 0.6 |

| DNAprod (pgDNA HAU−1) | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 5.1 ± 0.2 |

| Protprod (ngprot HAU−1) | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.02 |

2.6. Analytics

2.6.1. Hemagglutination assay (HA‐assay)

The quantification of the influenza virus titers with the HA‐assay was done according to Kalbfuss et al. 25. The reported values are based on double measurements, against an internal standard, and given in logarithmic units of the HA‐activity (logHAU, 1.0 logHAU = 10 HAU 100 μL−1). The expected maximum relative standard deviation of this assay is ± 20%.

2.6.2. Total protein assay

The total protein concentration was determined using a Bio‐Rad protein assay (Bio‐Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) as described by Opitz et al. 26. The calibration curve was prepared using BSA (#A‐3912, Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in the range of 5 to 40 μgprot mL−1. All samples were dialyzed (14 kDa MWCO Membra‐Cel™, #0653.1, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) against 50 mM Tris/HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 and measured in triplicates. The standard solutions were prepared in the same dialysis buffer. The maximum relative standard deviation was ±6.1%.

2.6.3. DNA assay

The double‐stranded DNA content was quantified as described by Opitz et al. 26 using the Quant‐iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA reagent (#P‐7581, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). The samples were dialyzed as described in Section 2.6.2. The calibration standard was prepared with λ‐DNA (#D1501, Promega GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) in the same dialysis buffer, in the range of 4 to 1000 ngDNA mL−1. The maximum relative standard deviation was ±7.7%.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Design of experiments

This study investigated a set of membrane‐ and process‐related factors expected to have a significant impact on SCMA purification of cell culture‐derived influenza A virus.

The Rechtschaffner design chosen is a specific type of two‐level fractional factorial design requiring fewer experiments than a full factorial design but with resolution V, for which interactions between factors and quadratic terms are considered without cofounding 23, 24.

Based on the experiments performed (see design matrix, Table 2), each response was fitted using the partial least squares method. All non‐significant terms were excluded, resulting in the equations below (Eq. (2) to (5)).

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

According to these reduced model equations, ligand density, conductivity and virus titer in the feed stream (and interactions of these factors) describe completely the virus losses in the flow through (Eq. (2)), and the virus yield (Eq. (3)). Regarding the DNA and total protein content in the product fraction (Eq. (4) and Eq. (5)), the NaCl concentration in the elution buffer and the flow rate have additionally to be considered. Interestingly however, the membrane permeability, which depends on the pore size of the membrane backbone, is not a significant factor to describe the responses investigated, within the tested range. This offers the option to either use a tighter membrane backbone generating a relatively large surface for functionalization or, a more open membrane to achieve higher membrane permeability and a low pressure drop.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the regression model (Eqs. (2) to (5)) and its significance (Table 3). The regression model was significant for all responses (p‐values < 0.05). Moreover, the lack of fit of the model was not significant (Fcrit ≤ 2.8, for all responses). Taken together, Eq. (2) to (5) are adequate to describe the corresponding experiments and the impact of the selected factors on the responses. Furthermore, the explained variation (R 2, ≥0.61), the predicted variation (Q 2, ≥0.16), model validity (>0.25), and reproducibility (>0.5) are within the accepted ranges for the design chosen 23. The only exception is the reproducibility (0.19) of the virus yield. Here, it must be considered that the responses are calculated as ratios, either based on the mass balance to the virus titer (for FTvirus and yield) or on the measured concentrations (DNAprod and Protprod). Given the rather high standard deviation of the assays, especially for the HA assay (see Section 2.6), and considering error propagation, low reproducibility values are to be expected.

Table 3.

ANOVA for the proposed Rechtschaffner design. The predicted variation (Q2), validity, and reproducibility of the model are also reported for each response

| Response | Degrees of freedom | p‐value | Lack of fit | F‐value | R 2 | Q 2 | Validity | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTvirus | 23 | 2.10e‐6 | 0.80 | 16.0 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.94 | 0.52 |

| Yield | 22 | 5.54e‐4 | 0.83 | 6.82 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.95 | 0.19 |

| DNAprod | 19 | 8.92e‐5 | 0.79 | 8.18 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 0.94 | 0.51 |

| Protprod | 19 | 8.08e‐4 | 0.35 | 6.06 | 0.69 | 0.16 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

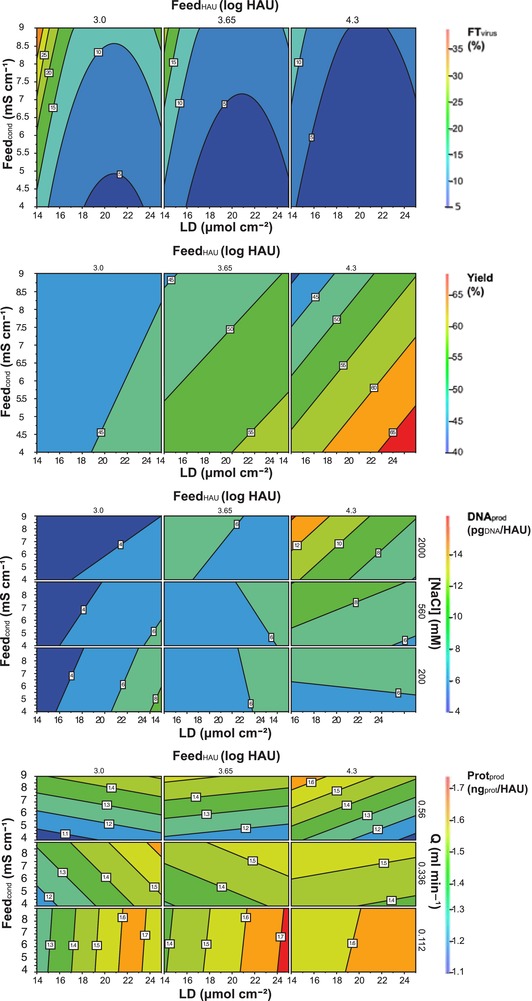

The regression model equations can be graphically represented by contour plots (Fig. 1A–D). Overall, virus losses (Fig. 1A) between approximately 5 and 35% were predicted. These were the lowest (<5%) for feed streams with higher titers. Lower losses in the flow through are also expected in SCMA with higher ligand density, i.e. more available binding sites. However, the effect of the quadratic term of this factor (Eq. (2)), also seen in the curvature of the contour lines (Fig. 1A), needs to be considered. There is a central range of ligand densities where virus losses in the flow through are low. One possible reason is that, for very high ligand densities, non‐specific interactions with contaminating proteins become more likely. Finally, these losses are minimized for feed streams with low conductivity. Most likely this is due to the fact that a high concentration of salt ions in the feed solution results in competition for the binding sites and/or masking of the charge of the virus particles, hindering the interaction with the stationary phase. This is in accordance to what was observed for Capto™ DeVirs bead‐based separations of various strains of influenza A and B viruses performed at conductivities below 5 mS/cm 27.

Figure 1.

Contour plots of interaction of the factors describing virus loss in the flow through (A, FTvirus), yield (B) and DNA (C, DNAprod) and total protein (D, Protprod) content in the product fraction, according to the predicted model (see Section 3.1, Eqs. (2) to (5). Membrane ligand density (LD), feed stream conductivity (Feedcond), virus titer in the feed stream (FeedHAU), flow rate (Q), and salt concentration in the elution buffer ([NaCl]).

Within the design space tested, the model predicts virus yields between 40% and 65% (Fig. 1B) that are strongly influenced by the virus titer in the feed stream (present in all interaction terms of Eq. (3)). The lower the virus titer is, the lower the predicted yield. Although the adsorption process of virus to sulfated matrices is not well described, this is an indication that the design space focuses on a range of the adsorption isotherm where the concentration of viruses adsorbed still depends on its concentration in solution. Higher virus yields are also expected for conditions that reduce virus losses, i.e. low feed conductivity and higher ligand density of the SCMA (Fig. 1A).

The DNA content in the product fraction is predicted to be between 4 and 16 pgDNA HAU−1 (Fig. 1C). Briefly, the lowest values, 4 to 6 pgDNA HAU−1, would be obtained for conditions (LD, Feedcond and FeedHAU) that result in lower virus yields (Fig. 1B). This indicates that the DNA is, to some extent, co‐eluting with the virus. This phenomenon was already observed by Opitz et al. 10 using a comparable membrane for influenza virus purification. One possible explanation is an interaction between DNA and the virus particles. Jeon et al. 28 and Choi et al. 29 described similar interactions between specific DNA aptamers and the receptor binding region of hemagglutinin, the most abundant surface protein in influenza virus type A and B. Nevertheless, all experimental runs of the design space tested in this work allowed to remove more than 99% of the DNA initially present in the feed stream (data not shown). Concerning the NaCl content of the elution buffer, the lowest DNA content values were obtained for low salt concentrations. If this is combined with optimal factors to reduce virus losses and to optimize virus yield as discussed above, the DNA content in the product fraction should remain <8 pgDNA HAU−1 with a low influence of the ligand density of the membrane adsorber.

Total protein content in the product fraction (Fig. 1D) varied in a range from 1.1 to 1.8 ngprot HAU−1. To interpret this result, it has to be taken into account that viral proteins are measured together with proteins from the medium and the cells. Accordingly, a higher protein content can be due to a higher virus recovery. Unfortunately, for the MDCK cells used in influenza virus production, there is no specific assay for host cell proteins commercially available. Therefore, it is not possible to differentiate between host cell proteins and viral proteins, and it is only possible to make a generalized evaluation of the factors influencing this response. As shown in Fig. 1D, the flow rate during the elution step significantly influences the total protein content in the product fraction. For lower flow rates (∼0.11 mL min−1), it is almost independent of the feed conductivity and strongly dependent on the ligand density, especially for lower virus titers. This behavior is reversed for high flow rates (∼0.56 mL min−1).

3.2. Optimization of the process performance

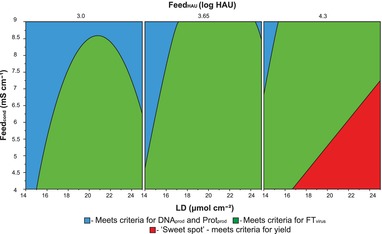

The next step on the evaluation of the experimental data and the resulting regression model was the prediction of the SCMA performance for a set of conditions optimizing process performance. First, the criteria for the responses were established. The objective were, within the predictable range, to minimize virus losses in the flow through (1.8 ≤ FTvirus ≤ 10%), to maximize virus yield (50 ≤ yield ≤ 68.1%), and to minimize the amount of DNA (2.9 ≤ DNAprod ≤ 8.5 pgDNA HAU−1) as well as the total protein content (1.0 ≤ Protprod ≤ 1.8 ngprot HAU−1) in the product fraction. The Optimizer tool was used to determine the design space, which meets all criteria known as the ‘Sweet spot’ (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Sweet spot plot for the optimization of process performance by minimizing virus losses (1.8 ≤ FTvirus ≤ 10%), maximizing virus yield (50 ≤ yield ≤ 68.1%), and minimizing the content of DNA (2.9 ≤ DNAprod ≤ 8.5 pgDNA HAU−1) as well as of total protein (1.0 ≤ Protprod ≤ 1.8 ngprot HAU−1) in the product fraction. The area where all objectives are met is indicated in red.

Figure 2 confirms the observations from the contour plots (Section 3.1). The flow rate and the salt concentration of the elution buffer had no influence on the ‘Sweet spot’. The objectives for DNA and total protein content in the product fraction are met in the complete design space of ligand density, feed conductivity and virus titer. The quadratic term of the ligand density relates to the shape of the region that additionally fulfills the FTvirus objective (green region under the curve, Fig. 2). Finally, the condition for the virus yield defines the ‘Sweet spot’ (in red, in Fig. 2). In conclusion, the higher the feed conductivity, the higher ligand density should be selected for maximum virus yield within the conditions established. If the feed stream is conditioned to a low conductivity, <4.5 mS cm−1, medium to high ligand densities can be used (18 <LD < 25 μmol cm−2).

The Predictor tool of the DoE software was then used to estimate a ‘robust set point’ using a Monte Carlo simulation (resolution 32, 10 000 simulations per point, confidence level 95%). This point represents the best set of factors that result in the best response output with the lowest probability of outliers of the Design Space 23. The membrane permeability was not considered as it is not part of the regression model. A normal distribution was assumed for all remaining factors. The predicted factors and responses obtained for this set point are summarized in Table 4. All resulting response profiles showed a normal distribution (data not shown), for which 95% fulfill: 1.7% ≤ FTvirus ≤ 3.5%, 54.9% ≤ yield ≤ 61.5%, 5.0 ≤ DNAprod ≤ 6.6 pgDNA HAU−1, and 1.3 ≤ Protprod ≤ 1.5 ngprot HAU−1. FTvirus together with DNAprod are the responses with the highest relative standard deviation.

3.3. Experimental validation of robust set point

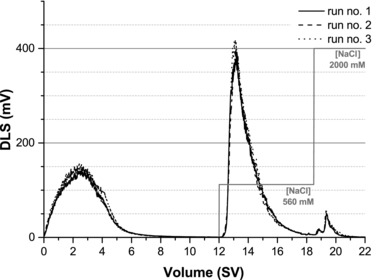

In a final step, three replicate runs were carried out to validate experimentally the robust set point predicted (see Section 3.2, Table 4). The experimental conditions are summarized in Table 4. The choice of ligand density for set point validation was restricted by the prototypes available. The membrane selected had a ligand density of 20.0 μmol cm−2 and a corresponding membrane permeability of 106 mL (min bar cm2)−1. The difference between the ligand density of this prototype and the suggested value (0.6 μmol cm−2) was considered acceptable considering the predicted standard deviation. The optimal flow rate value (0.375 mL min−1) was changed to 0.38 mL min−1, which corresponds to the best approximation which can be adjusted for the ÄKTA system. The salt concentration in the elution buffer was 560 mM. The virus feed stream was adjusted to the proposed feed conductivity (4.7 mS cm−1) at the appropriate dilution (FeedHAU = 3.8 logHAU).

Figure 3 shows the chromatograms obtained using on‐line DLS measurements. The DLS signal is specific for the presence of larger molecules, e.g. the virus particles, but not quantitative. The peaks at about 14 SV correspond to the elution of the virus at 560 mM NaCl. Table 4 shows the average responses obtained for the three replicates. The robust set point conditions resulted in 57.4 ± 0.6% virus yield and 2.1 ± 1.5% losses in the flow through. The values obtained for DNA and total protein content in the product fraction were 5.1 ± 0.2 pgDNA HAU−1 and 1.2 ± 0.02 ngprot HAU−1, respectively. In all cases, the experimental values did not differ significantly from the values predicted by the model (independent samples two‐tailed Student's t‐test with α = 0.05).

Figure 3.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) chromatograms of three technical replicates of chromatographic separations using SCMA under optimized conditions using a ligand density of 20.0 μmol cm−2, a flow rate of 0.38 mL min−1, and a concentration of NaCl in the elution step of 560 mM. The virus feed stream had a final virus titer of 3.8 log HAU and was conditioned to a conductivity of 4.8 mS cm−1.

The purification of the same influenza A virus strain produced in animal cell cultures using similar SCMA has been reported before 10, 12. Opitz et al. 10 reported virus losses in the flow through of 21.4%, and a virus yield of 81.6%. DNA and total protein content in the product fraction were 20.2 ± 2.2 pgDNA HAU and 1.8 ± 0.3 ngprot/HAU, respectively. Using the same conditions as Opitz et al. 10, Weigel et al. 12 reported similar virus yields (79.0 ± 8.9%) but losses of of 5.3 ± 0.9%, 5.7 ± 0.6 pgDNA HAU−1 and 0.6 ± 0.1 ngprot HAU−1. Compared to results obtained in this study, both virus yields and virus losses in the flow through fraction were slightly higher. Furthermore, the DNA and the total protein content in the product fraction were in the same order of magnitude, considering the error of the analytical assays and that, although a comparable virus titer was used in both studies (FeedHAU 3.3–3.7 logHAU), the feed stream in those cases was produced in different conditions, i.e. MDCK cells grown in serum‐containing media. Opitz et al. 10 also investigated the influence of the salt concentration in the feed stream on virus losses in the flow through, using 50 mM and 150 mM NaCl in 10 mM TRIS/HCl, pH 8 buffer. They concluded that 50 mM NaCl leads to lower losses. This salt concentration corresponds to approximately 5 mS/cm and it is therefore comparable to the feed conductivity suggested for the optimal operating point. In contrast, Weigel et al. 12 used a 1:2 dilution of their feed stream with 10 mM TRIS/HCl pH 7.4 buffer and it is not possible to compare the conductivity of the feeds. In both cases, the salt concentration used for elution was 600 mM, close to the 560 mM suggested for the robust set point. Another significant difference is found on the flow rates used. With a flow rate of 0.38 mL min−1, the prediction for the robust set point was about 10‐fold higher than in the previous studies. Based on the results obtained, the volumetric productivity of SCMA is clearly higher than anticipated. Finally, most likely the properties of membranes used in the various studies differed. While similar conditions where used in all studies, earlier work involved in‐house modification of cellulose membranes while the prototype membranes used here were produced at pilot scale by an industrial partner under highly controlled conditions. As the membranes used in the previous studies are not available anymore, it is unfortunately not possible to compare their ligand densities, and to draw conclusions in this respect.

4. Concluding remarks

In this work, a DoE approach was used to screen six factors regarding their impact on the purification of influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 using SCMA. Two factors were related to specific properties of the membrane adsorbers, i.e. ligand density and membrane permeability. Four other factors to operating conditions (flow rate, salt concentration in the elution buffer, virus titer in the feed stream, and conductivity of the feed stream). Ligand density as well as conductivity and virus titer in the feed stream were the factors with the highest impact on the purification performance of the SCMA. The optimal set of factors predicted using the model identified by the chosen DoE approach was experimentally verified with three technical replicates. It resulted in 2.1 ± 1.5% virus loss in the flow through, a yield of 57.4 ± 0.6% and a final DNA and total protein content in the product fraction of 5.1 ± 0.2 pgDNA HAU−1 and 1.2 ± 0.02 ngprot HAU−1, respectively. These values are in good agreement with the prediction. Accordingly, SCMA can be considered as a valuable option for downstream processing of cell culture‐derived influenza viruses besides ultracentrifugation or the use of bead‐based matrices. In contrast to earlier studies performed for the same virus strain, results obtained by the DoE approach stressed the impact of the virus feed concentration on yield and strongly suggest the use of high flow rates to optimize volumetric productivity. Based on the future availability and the specific design of commercial SCMA, follow‐up studies should be performed to include more virus strains and additional factors (e.g. pH value, conditioning buffer) to further evaluate the performance and robustness of SCMA as a platform technology for vaccine production.

Practical application

This study presents a systematical evaluation of the influence of several parameters regarding the use of sulfated cellulose membrane adsorbers for the purification of cell derived influenza A virus particles. A design of experiments approach enabled a resource and time effective optimization of the process conditions. Membrane ligand density, conductivity of the feed conditioning buffer, and virus concentration in the feed stream were identified as the most important factors for virus yields and low protein as well as DNA contamination levels in the product fraction. Results obtained are an excellent basis for future studies on the use of the sulfated cellulose membrane adsorbers for downstream processing not only of other influenza virus strains but also for other types of heparin binding viruses or virus‐like particles.

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), project grant number 0315640C. The authors thank for the support of the technical assistants of the Bioprocess Engineering group at the Max Planck Institute in Magdeburg, i.e. L. Fichtmüller, A. Bastian and I. Behrendt. Additionally, the authors also thank the technical staff of the R&D membrane development group at Sartorius Stedim Biotech GmbH for providing the membrane prototypes.

5 References

- 1. Lohr, V. , Genzel, Y. , Behrendt, I. , Scharfenberg, K. , et al. A new MDCK suspension line cultivated in a fully defined medium in stirred‐tank and wave bioreactor. Vaccine 2010, 28, 6256–6264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kon, T. C. , Onu, A. , Berbecila, L. , Lupulescu, E. , et al. Influenza vaccine manufacturing: effect of inactivation, splitting and site of manufacturing. comparison of influenza vaccine production processes. Plos One 2016, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolff, M. , Reichl, U. Downstream processing of cell culture‐derived virus particles. Exp. Rev. Vacc. 2011, 10, 1451‐1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Genzel, Y. , Vogel, T. , Buck, J. , Behrendt, I. , et al. High cell density cultivations by alternating tangential flow (ATF) perfusion for influenza A virus production using suspension cells. Vaccine 2014, 32, 2770–2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wolff, M. W. , Reichl, U . Downstream Processing: From egg to cell culture‐derived influenza virus particles. Chem. Engin. Technol. 2008, 31, 846‐857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morenweiser, R. Downstream processing of viral vectors and vaccines. Gene Therapy 2005, 12, S103‐S110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rabenstein, D. L. Heparin and heparan sulfate: structure and function. Natural Product Reports 2002, 19, 312–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oka, T. , Ohkuma, K. , Kawahara, T. , Sakoh, M. A method for purification of influenza virus. EP 0171086 B1, 1986.

- 9. Sakoda, Y. , Okamatsu, M. , Isoda, N. , Yamamoto, N. , et al. Purification of human and avian influenza viruses using cellulose sulfate ester (Cellufine Sulfate) in the process of vaccine production. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012, 56, 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Opitz, L. , Lehmann, S. , Reichl, U. , Wolff, M. W. Sulfated membrane adsorbers for economic pseudo‐affinity capture of influenza virus particles. Biotechnol. Bioengin. 2009, 103, 1144‐1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Opitz, L. , Lehmann, S. , Zimmermann, A. , Reichl, U. , et al. Impact of adsorbents selection on affinity purification efficiency of cell culture derived human Influenza viruses. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 131, 309‐317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weigel, T. , Solomaier, T. , Wehmeyer, S. , Peuker, A. , et al. A membrane‐based purification process for cell culture‐derived influenza A virus. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 220, 12‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wolff, M. , Reichl, U. , Opitz, L. Method for the preparation of sulfated cellulose membranes and sulfated cellulose membranes. US 8173021 B2, 2012.

- 14. Villain, L. , Hörl, H. H. , Brumm, C. Sulfated cellulose hydrate membrane, method for producing same, and use of the membrane as an adsorption membrane for a virus purification process. WO 2015/055269 A1, 2015.

- 15. Fields, B. N. , Knipe, D. M. , Palese, P. , Shaw, M. L. Orthomyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication, in: Knipe D. M., Howley P. M. (Eds.), Fields Virology, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa: u.a. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muthukumar, S. , Rathore, A. S. High throughput process development (HTPD) platform for membrane chromatography. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 442, 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tye, H. Application of statistical ‘design of experiments’ methods in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2004, 9, 485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carrier, T. , Heldin, E. , Ahnfelt, M. , Brekkan, E. , et al. High throughput technologies in bioprocess development, in: Flickinger M. C. (Ed.), Downstream Industry Biotechnology: Recovery and Purification, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nfor, B. K. , Verhaert, P. D. E. M. , van der Wielen, L. A. M. , Hubbuch, J. , et al. Rational and systematic protein purification process development: the next generation. Trends Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ji, Y. , Tian, Y. , Ahnfelt, M. , Sui, L. Design and optimization of a chromatographic purification process for Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 23F capsular polysaccharide by a Design of Experiments approach. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1348, 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Afonso, A. , Pereira, P. , Queiroz, J. A. , Sousa, Â. , et al. Purification of pre‐miR‐29 by a new O‐phospho‐l‐tyrosine affinity chromatographic strategy optimized using design of experiments. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1343, 119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Almeida, A. M. , Queiroz, J. A. , Sousa, F. , Sousa, A. Optimization of supercoiled HPV‐16 E6/E7 plasmid DNA purification with arginine monolith using design of experiments. J. Chromatogr. B 2015, 978–979, 145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.User Guide to MODDE. MKS Umetrics AB, Malmö 2015. Available on: http://umetrics.com/sites/default/files/download/1/modde_pro_11_user_guide.pdf.

- 24. Eriksson, L. Design of experiments: principles and applications. MKS Umetrics AB, 2008.

- 25. Kalbfuss, B. , Knöchlein, A. , Kröber, T. , Reichl, U. Monitoring influenza virus content in vaccine production: Precise assays for the quantitation of hemagglutination and neuraminidase activity. Biologicals 2008, 36, 145–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Opitz, L. , Salaklang, J. , Büttner, H. , Reichl, U. , et al. Lectin‐affinity chromatography for downstream processing of MDCK cell culture derived human influenza A viruses. Vaccine 2007, 25, 939‐947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Capto(TM) DeVirs ‐ Data File, GE Healthcare Bio‐Sciences AB, Uppsala 2009.

- 28. Jeon, S. H. , Kayhan, B. , Ben‐Yedidia, T. , Arnon, R. A DNA aptamer prevents influenza infection by blocking the receptor binding region of the viral hemagglutinin. J. Biological Chem. 2004, 279, 48410–48419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Choi, S. K. , Lee, C. , Lee, K. S. , Choe, S.‐Y. , et al. DNA aptamers against the receptor binding region of hemagglutinin prevent avian influenza viral infection. Mol. Cells 2011, 32, 527–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]