Abstract

Background

It is still uncertain whether coronary bifurcations with lesions involving a large side branch (SB) should be treated by stenting the main vessel and provisional stenting of the SB (simple) or by routine two-stent techniques (complex). We aimed to compare clinical outcome after treatment of lesions in large bifurcations by simple or complex stent implantation.

Methods

The study was a randomised, superiority trial. Enrolment required a SB≥2.75 mm, ≥50% diameter stenosis in both vessels, and allowed SB lesion length up to 15 mm. The primary endpoint was a composite of cardiac death, non-procedural myocardial infarction and target lesion revascularisation at 6 months. Two-year clinical follow-up was included in this primary reporting due to lower than expected event rates.

Results

A total of 450 patients were assigned to simple stenting (n=221) or complex stenting (n=229) in 14 Nordic and Baltic centres. Two-year follow-up was available in 218 (98.6%) and 228 (99.5%) patients, respectively. The primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at 6 months was 5.5% vs 2.2% (risk differences 3.2%, 95% CI −0.2 to 6.8, p=0.07) and at 2 years 12.9% vs 8.4% (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.13, p=0.12) after simple versus complex treatment. In the subgroup treated by newer generation drug-eluting stents, MACE was 12.0% vs 5.6% (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.17, p=0.10) after simple versus complex treatment.

Conclusion

In the treatment of bifurcation lesions involving a large SB with ostial stenosis, routine two-stent techniques did not improve outcome significantly compared with treatment by the simpler main vessel stenting technique after 2 years.

Trial registration number

Keywords: coronary bifurcations, complex coronary lesions, drug eluting stents

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Previous comparisons of one-stent and two-stent techniques for coronary bifurcation stenting have shown conflicting results but indicated that most bifurcations with large side branches (SBs) are effectively treated by the simple provisional SB stenting technique. Two-stent techniques have important procedural advantages in allowing for securing the SB first in cases with difficult SB access or high risk of occlusion.

What does this study add?

Patients with a coronary bifurcation lesion involving a large side branch (SB) may be treated safely using a two-stent technique, in particular when using newer generation drug-eluting stents. As many patients had no need for a second stent in the simple provisional stenting group, future research should focus on evaluation of tools for identification of lesions requiring SB treatment.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Using newer generation drug-eluting stents, there is at least no penalty in treating coronary bifurcation lesions with two-stent techniques.

Introduction

Coronary bifurcations are predilection site for atherosclerosis due to regions of low endothelial shear stress resulting in pathological intimal thickening and plaque formation.1 Treatment of bifurcation lesions constitute about 15% of coronary interventions and are consequently of major clinical interest. Currently, the simple, provisional side branch (SB) stenting technique is the recommended strategy for bifurcation lesion treatment.2–8 With one exception,9 previous studies have shown no benefit of preplanned two-stent techniques in comparison to the simple strategy. In simple provisional SB stenting, a stent is deployed in the main vessel (MV) across the SB, and if needed, the SB is subsequently treated by balloon dilatation or stent implantation.10 Planned stenting of both MV and SB may be accomplished using a number of different techniques, such as T-stenting, T and protrude (TAP), culotte and crush techniques. In earlier studies on simple versus complex bifurcation stenting, inclusion of patients with small and possibly physiological insignificant SBs was a major limitation for extending results to clinically important bifurcation lesions involving a large SB.2 4–6 10 Therefore, we designed the present study to address the unsolved question of simple provisional SB stenting versus complex two-stent treatment in patients with bifurcation lesions involving a large SB.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

The Nordic Baltic Bifurcation Study IV (Nordic Baltic IV) was a prospective, randomised, multicentre trial comparing the simple provisional SB stenting technique versus complex stenting of both the MV and the SB in the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions. A total of 450 patients were included from December 2008 to December 2012 in centres in Norway, Sweden, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia and Denmark. Inclusion criteria were stable angina pectoris, unstable angina pectoris or silent ischaemia, a ‘true’ bifurcation lesion (Medina 1.1.1 or 1.0.1 or 0.1.1), lesion11 in the left anterior descending artery (LAD)/diagonal, circumflex artery (Cx)/obtuse marginal branch, right coronary artery/posterior descending artery/posterolateral branch, or left main coronary artery (LMCA)/LAD/Cx with an MV diameter ≥3.0 mm and SB diameter ≥2.75 mm by visual estimate. Exclusion criteria were ST-elevation myocardial infarction within 24 hours, SB lesion length >15 mm, expected survival <1 year, s-creatinine >200 µmol/L, allergy to aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, sirolimus or everolimus. All patients provided written informed consent.

Randomisation procedure

When guide wires were inserted in both the MV and the SB, eligible patients were randomised 1:1 to the simple or the complex group by an independent web-based trial management system (TrialPartner, Public Health and Quality Improvement, Central Denmark Region, Aarhus, Denmark). Randomisation was performed in permutated blocks by centre with stratification according to gender, age>70 years, diabetes mellitus and participation in the angiographic substudy. Neither the operator nor the patients were blinded to the treatment allocation.

Study procedure

Radial or femoral approach was allowed using 6–8F guiding catheters. Unfractionated heparin, low-molecular weight heparin or bivalirudin and GPIIbIIIa inhibitors were used according to local hospital routine. The recommended implantation steps in the simple group were (1) predilatation of stenosed areas of the MV to be covered by stent, (2) therapeutic dilatation of the SB using a balloon with a diameter equal to or greater than the SB reference size and (3) stenting of the MV, jailing the SB wire. If normal flow (Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow=III) was achieved in both the MB and the SB, and there was less than 75% residual diameter stenosis of the SB ostium, the procedure was terminated. Kissing balloon inflation (KBI) was indicated if TIMI flow <III, or if the SB ostium had more than 75% diameter stenosis after MV stenting. In case of TIMI flow <III after KBI, stenting the SB was indicated using a T-stenting12 or the culotte technique.13 Final KBI was mandatory if the SB was stented.

The culotte implantation technique was recommended for planned complex stenting. Other two-stent techniques were allowed at the operator’s discretion except classic crush14 and simultaneous kissing stent (SKS) techniques.15 Final KBI was mandatory in any two-stent procedure.

Lifelong aspirin was prescribed to all patients and clopidogrel was indicated for 12 months. Ticlopidine was indicated if patients did not tolerate clopidogrel. The sirolimus eluting stent ‘Cypher Select+’ (Cordis, USA) was the study stent in the first 225 patients and the Xience V or Xience Prime, everolimus eluting stents (Abbott, USA) were the study stent in the remaining 225 patients. The change in study stent during enrolment was a post hoc adjustment, as the Cypher stent supply was unexpectedly discontinued during the enrolment period. If the study stents could not be implanted, another drug-eluting stent (DES) or bare metal stent was allowed at the discretion of the operator. Different types of DES were not allowed in the same vessel.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the composite of major adverse cardiac events (MACE); cardiac death, non-procedural myocardial infarction, clinically indicated target lesion revascularisation and definite stent thrombosis within 6 months after the index procedure. Secondary endpoints were the composite MACE endpoint at 2 years, all-cause mortality, cardiac death, non-procedural myocardial infarction, clinically indicated target lesion revascularisation or target vessel revascularisation, and definite, probable or possible stent thrombosis.

Endpoint definitions

Cardiac death was defined as death from coronary artery disease including myocardial infarction, sudden death with a possible or definite cardia cause, death from heart failure including cardiogenic shock, and death related to a cardiac procedure within 28 days from the procedure. Cardiac death did not include death due to pulmonary embolism, cerebrovascular attacks or other vascular but non-cardiac events. Non-procedural myocardial infarction required evidence of myocardial necrosis by at least one of the following criteria: (1) detection of a rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarkers with at least one value above the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit (URL) and evidence of ischaemia in the myocardium documented by either symptoms of ischaemia, ECG changes indicative of acute ischaemia (new ST-T changes, new left bundle branch block (LBBB), new pathological Q waves in the ECG), evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new cardiac wall motion abnormality. (2) Sudden and unexpected cardiac death with at least one of the following: cardiac arrest, symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischaemia, presumably new ST-segment elevation, or new LBBB, and/or evidence of fresh thrombus by coronary angiography and/or at autopsy. (3) Pathological findings suggestive of acute myocardial infarction.16 Assessment of procedural cardiac biomarkers was recommended. In patients with normal baseline biomarker values, elevations of cardiac biomarkers (CK-MB) greater than 3×99th percentile URL defined index procedure-related myocardial infarction. Patients with stable angina pectoris or silent ischaemia were considered to have normal baseline markers if values were not assessed. If cardiac biomarkers were elevated before the procedure and not stable in two samples 6 hours apart, the diagnosis of periprocedural myocardial biomarker increase could not be made. If biomarker values were stable or falling, a 20% or more increase of the value in the second sample after the procedure was required. Elevations of CK-MB greater than 3×99th percentile URL and greater than 5×99th percentile URL were assessed independently. Stent thrombosis was classified as definite, probable or possible, and definite stent thrombosis was categorised as acute, subacute, late and very late according to the Academic Research Consortium(ARC) criteria.17 Target lesion revascularisation was defined as repeat revascularisation by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass surgery of the target lesion defined as the stented or balloon-treated segments and their 5 mm margins in all three coronary branches.

Quantitative coronary analysis

Coronary angiograms of pre-PCI, post-PCI and 8-month follow-up were analysed by the Core laboratory for interventional coronary imaging, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark and by Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia, using validated software dedicated to segmental bifurcation analysis (QAngioXA 7.3, Medis Medical Imaging, Leiden, The Netherlands). All included patients had assessment of pre-PCI and post-PCI angiograms and follow-up angiograms were analysed in patients completing the 8-month angiographic follow-up. Analysis principles of the dedicated bifurcation quantitative coronary analysis (QCA) for the Nordic-Baltic bifurcation studies were previously reported.18 The analysed segments were the proximal MV, distal MV and SB. The bifurcation core segment was analysed in combination with the proximal MV. The three edge segments comprised the 5 mm margins to the stented, or balloon treated segments. If the SB was not treated by stent or balloon, the first 5 mm of the SB was defined as both the lesion and the edge segment. Binary (re)stenosis was defined as ≥50% diameter stenosis. All analyses were cross-evaluated by the same second observer to ensure consistency in methods between the two core laboratories. The QCA was not blinded due to the evident appearance of simple or complex stenting techniques in the analysed angiograms.

Sample size

The sample size estimate for the primary superiority outcome measure of 6-month MACE was based on the limited available evidence at conceptualisation of the study. With expected MACE rates of 10% in the simple group and 3% in the complex group, α=0.05 and power=0.80, a sample of 194 patients were required in each group (two-sided χ2 test). Sample size was initially set to 400 patients in total but was increased during enrolment to 450 patients to accommodate for potential lower than expected event rates and patients lost to follow-up.

Statistics

Categorical variables are reported as number and percentages and were analysed using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test if 2×2 cell values were below five. Continuous variables following a Gaussian distribution were analysed by the independent sample t-test and presented as mean±SD. Non-Gaussian variables were analysed by Mann-Whitney U-test and presented as median and IQR. Rates of the primary endpoint of 6-month MACE and its individual components are presented as risk differences. Two-year outcomes are resented as Kaplan-Meier estimates, HRs and 95% CIs, and were compared by unadjusted Cox regression analysis. The analysis was performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Patients lost to follow-up were censored at day of withdrawal or last contact. Post hoc subgroup analysis was performed by Cox regression analysis with test for interaction of the subgroup variable and treatment allocation. Results are given as HR and 95% CI and presented by forest plot. Per protocol analysis for 2-year MACE excluded any patient that did not receive an MV stent and patients in the two-stent group without SB stenting. Two-sided p values below 0.05 indicated significance. All analyses were performed using STATA V.12 (STATA Corp, Texas, USA).

Results

Patient and lesion characteristics

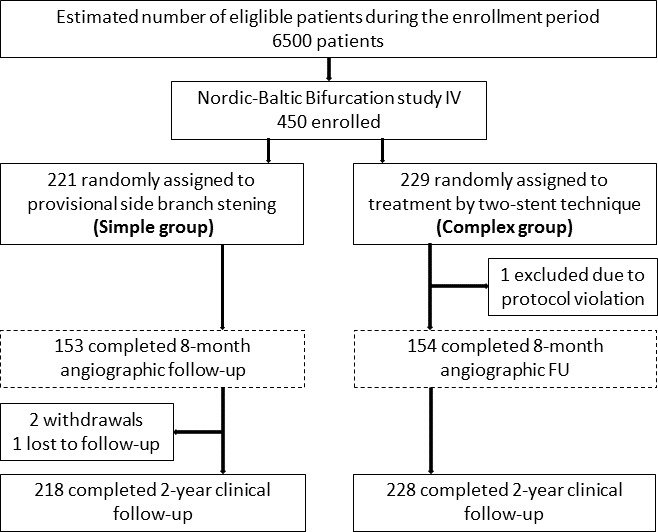

A total of 450 patients were assigned to simple stenting (n=221) or complex stenting (n=229) (figure 1). Two-year follow-up was available in 446 patients. Age was 64±12 vs 63±11 years, 16.3% and 15.3% had diabetes and 39.1% vs 35.3% had prior coronary artery bypass grafting or PCI in simple and complex groups, respectively (table 1). The predominant lesion location was LAD and diagonal (74.1% vs 76.7%). Reference diameter by visual estimate of the MV was 3.5±0.4 mm and 3.4±0.3 mm (p=0.02), and the SB reference diameter was 2.9±0.2 mm and 2.9±0.2 mm by visual estimate and 2.4±0.5 mm and 2.5±0.5 mm by QCA in simple and complex groups, respectively (table 2). Mean SB stenosis before treatment by visual estimate was 74.4%±14.4% and 77.1%±12.1%, p=0.04, and by QCA was 44.3%±18.5% and 47.3%±17.6%, p=0.95 for simple and complex groups, respectively (table 3: QCA for angiographic follow-up group results).

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart. *Numbers in the two groups are not balanced at baseline due to block randomisation and sites with less than four inclusions. MV, main vessel; SB, side branch; FU, follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics values are mean±1 SD or n (%)

| Simple n=218 | Complex n=228 | P value | |

| Age (years) | 64±12 | 63±11 | 0.25 |

| Current smoker | 41 (18.9%) | 48 (21.1%) | 0.56 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 178 (82.0%) | 184 (81.1%) | 0.79 |

| Hypertension | 152 (70.0%) | 149 (65.6%) | 0.32 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 36 (16.5%) | 35 (15.4%) | 0.74 |

| Family history | 108 (50.5%) | 107 (47.4%) | 0.51 |

| Prior PCI | 77 (35.5%) | 76 (33.5%) | 0.66 |

| Prior CABG | 8 (3.7%) | 4 (1.8%) | 0.21 |

| CCS class ≥2 angina | 205 (94.5%) | 213 (93.8) | 0.98 |

| Indication | |||

| Stable angina pectoris | 188 (86.6%) | 187 (82.4%) | 0.22 |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 28 (12.9%) | 38 (16.7) | 0.26 |

| Silent ischaemia | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0.34 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | |||

| Aspirin | 217 (100%) | 227 (100%) | 1 |

| Clopidogrel | 216 (99.5) | 227 (100%) | 1 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 62 (28.6) | 83 (36.9.1) | 0.06 |

| Bivalirudin | 26 (12.0%) | 33 (14.6%) | 0.42 |

CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; GP, glycoprotein receptor.

Table 2.

Lesion and procedural characteristics

| Simple n=218 | Complex n=228 | P value | |

| LVEF (%) | 57±6 | 56±7 | 0.10 |

| Lesion location | |||

| Left anterior descending artery | 161 (74.2%) | 174 (76.7%) | 0.55 |

| Circumflex artery | 36 (16.6%) | 40 (17.6%) | 0.77 |

| Right coronary artery | 14 (6.5%) | 9 (4.0%) | 0.24 |

| Left main stem | 6 (2.77%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0.28 |

| Calcification visible by angiography | 105 (48.4%) | 99 (43.6%) | 0.31 |

| Proximal tortuosity | 6 (2.8%) | 16 (7.0%) | 0.04 |

| Angulation less than 70 degrees | 107 (49.3%) | 111 (48.9%) | 0.93 |

| Mean lesion length*, mm | |||

| Main vessel | 20.8±9.9 | 19.5±8.9 | 0.15 |

| Side branch | 6.4±4.1 | 7.7±4.9 | <0.0001 |

| Proximal reference diameter*, mm | |||

| Main vessel | 3.5±0.4 | 3.4±0.3 | 0.02 |

| Side branch | 2.9±0.2 | 2.9±0.2 | 0.16 |

| Side branch predilated | 140 (64.2%) | 177 (78.0%) | – |

| Main vessel stented | 238 (99.6) | 238 (100) | 1.00 |

| Side branch stented | 8 (3.7%) | 219 (96.5%) | – |

| Length of stented main vessel segment*, mm | 25.0±9.5 | 24.3±9.6 | 0.34 |

| Length of stented side branch segment*, mm | 13([8:15) | 9(6:13) | – |

| Side branch predilatation or final kissing balloon inflation | 171 (78.4%) | – | – |

| Final kissing balloon inflation | 79 (36.1%) | 208 (91.2%) | – |

| Treatment successful† | 212 (97.7%) | 226 (98.7%) | 0.14 |

| Procedure time, min | 41.8±33.2 | 67.9±27.6 | <0.0001 |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 13.9±8.8 | 22.8±12.8 | <0.0001 |

| Contrast volume, mL | 187±81 | 231±86 | <0.0001 |

Values are mean±1 SD or n (%).

*By visual estimate.

†Residual stenosis <30%, of main vessel and Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) III flow in side branch.

FKBI, final kissing balloon inflation; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table 3.

Quantitative coronary angiography at baseline and at 8-month angiographic follow-up in a subgroup of patients randomised to simple versus complex coronary bifurcation stenting

| Segment | Proximal main vessel | Distal main vessel | Side branch | ||||||

| Simple n=153 | Complex n=154 | P value | Simple n=153 | Complex n=154 | P value | Simple n=153 | Complex n=154 | P value | |

| In-stent minimal luminal diameter, mm | |||||||||

| Pre-PCI | 1.29±0.55 | 1.41±0.60 | 0.96 | 1.43±0.55 | 1.43±0.58 | 0.51 | 1.43±0.69 | 1.21±0.46 | 0.0008 |

| Post-PCI | 3.05±1.46 | 2.84±1.48 | 0.11 | 2.45±0.42 | 2.51±0.41 | 0.89 | 1.59±0.65 | 2.10±0.37 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up | 2.76±0.54 | 2.65±0.56 | 0.06 | 2.48±0.49 | 2.42±0.53 | 0.30 | 1.77±0.70 | 2.07±0.51 | <0.001 |

| Reference diameter, mm | |||||||||

| Baseline | 3.13±0.47 | 3.20±0.57 | 0.86 | 2.57±0.46 | 2.61±0.54 | 0.74 | 2.33±0.49 | 2.40±0.49 | 0.59 |

| In-stent diameter stenosis, % | |||||||||

| Pre-PCI | 59±16 | 57±17 | 0.17 | 40±20 | 43±22 | 0.25 | 43±18 | 49±17 | 0.99 |

| Post-PCI | 11±9 | 8±7 | 0.005 | 11±9 | 11±9 | 0.49 | 36±19 | 17±11 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up | 12±11 | 10±8 | 0.01 | 12±10 | 15±12 | 0.97 | 32±20 | 21±17 | <0.001 |

| In-stent late lumen loss, mm | |||||||||

| 0.27±1.48 | 0.08±1.52 | 0.14 | −0.10±0.45 | −0.03±0.47 | 0.89 | −0.20±0.66 | 0.03±0.52 | 0.99 | |

| In-segment binary restenosis, n (%) | |||||||||

| Follow-up | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.7) | 0.56 | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | 0.99 | 31 (20.3) | 8 (5.2) | <0.001 |

Binary restenosis: ≥50% diameter stenosis at 8-month follow-up.

Fisher’s exact test, χ2 test or independent samples t-test were used.

*In-stent segments included the stented areas of the main vessel and or the first 5 mm of the side branch.

Procedural results

In the simple group, any SB balloon treatment was performed in 78.4% of cases and the SB was stented in 3.7% of cases. In the complex group, the techniques were culotte (65.6%), mini crush (21.5%), T-stenting (7.1%) or other (5.8%). The SB was stented in 96% and 91% had KBI. Reported causes for not stenting the SB in attempted two-stent techniques included (1) not able to pass balloon into the SB, and (2) not able to pass stents into the SB. Residual binary SB stenosis after treatment was 28.0% in the simple group and 2.7% (p<0.0001) in the complex group. Periprocedural biomarker release was assessable in 182 (83%) and 187 (82%) patients in the simple and complex stenting groups. The biomarkers were increased in 7.7% vs 9.6% (p=0.51) for CK-MB greater than 3×99th percentile URL and 5.0% vs 3.7% (p=0.57) for CK-MB greater than 5×99th percentile URL in the groups of simple and complex stenting, respectively.

Outcomes

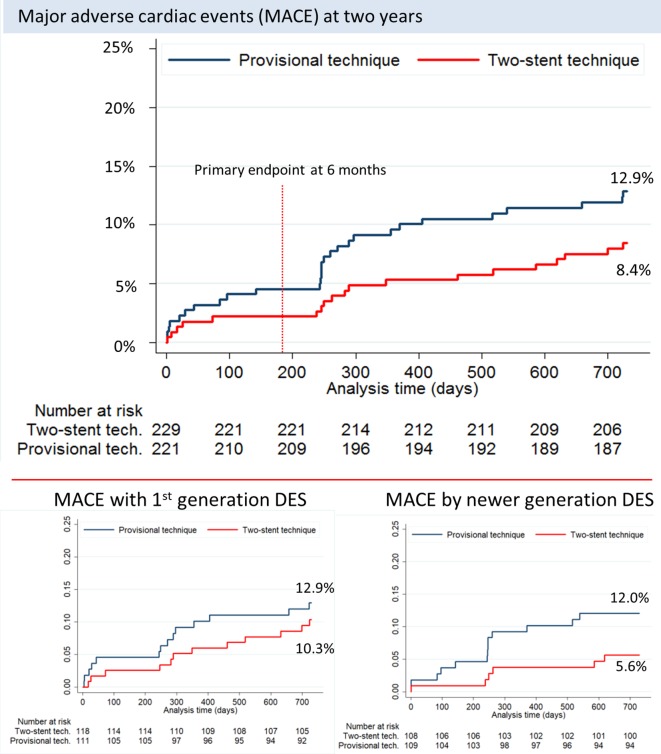

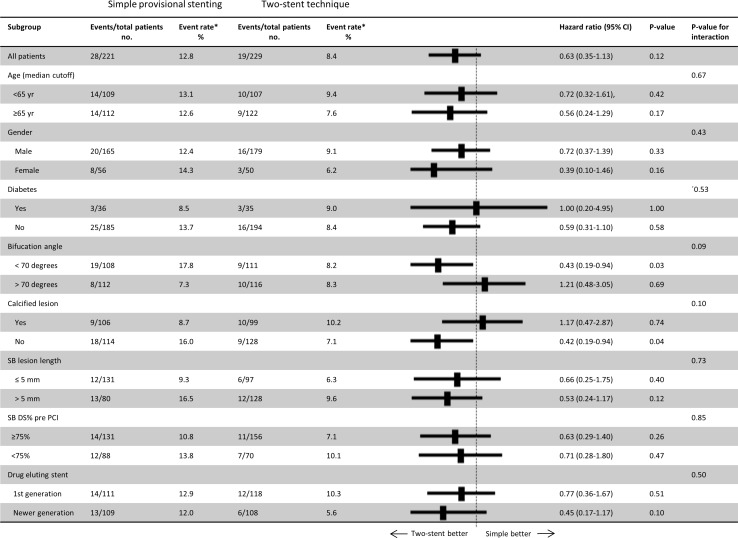

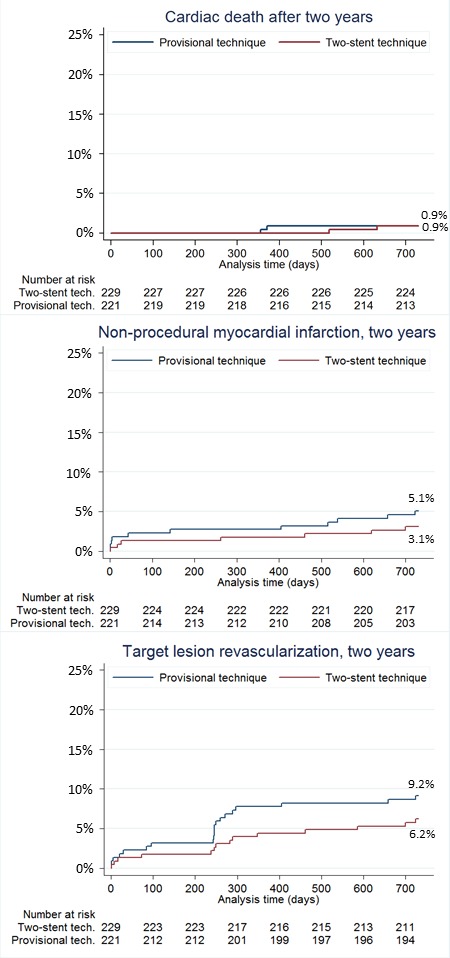

The primary endpoint of MACE at 6 months was 5.5% vs 2.2% (RD 3.2%, 95% CI −0.2 to 6.8, p=0.07) and at 2 years 12.9% vs 8.4% (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.15, p=0.12) after simple versus complex treatment (figure 2). Individual endpoints at 6 months and 2 years are shown in figure 3 and table 4. Per protocol analysis for 2-year MACE was 12.9% in 218 vs 8.7% in 219 patients (p=0.16). Angina pectoris by Canadian Cardiovascular Society score ≥II at 2-year follow-up was 3.9% in the simple group and 4.1% in the complex group (RD −0.2%, 95% CI −4.0 to 3.4, p=0.89). In the subgroup treated by first generation DES, the rate of 2-year MACE rate was 12.9% vs 10.3% (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.67, p=0.51) and after treatment by newer generation DES MACE was 12.0% vs 5.6% (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.17, p=0.10) after simple versus complex treatment (figure 2). Other subgroup results are presented in figure 4. Eight-month angiographic follow-up was completed in 307 patients assigned to simple (n=153) or complex stenting (n=154). After the index procedure, SB binary residual stenosis was 28.0% vs 2.7% (p<0.001). After 8 months, the binary (re)stenosis rate was 1.3% vs 0.7% (p=0.56) in the proximal MV, 1.3% vs 1.3% (p=0.99) in the distal MV and 20.3% vs 5.2% (p<0.001) in the SB after simple versus complex stenting, respectively.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for major adverse cardiac events (MACE). Clinical event curves showing MACE rates until 2 years.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for clinical endpoints. Clinical event curves for cardiac death, non-procedural myocardial infarction and target lesion revascularisation until 2 years.

Table 4.

The individual components of MACE and clinical outcomes at 24 months

| Provisional side branch stenting (Simple) | Two-stent technique (Complex) | Risk difference (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Events at 6 months | Follow-up in 220 patients | Follow-up in 228 patients | ||

| MACE | 12 (5.5%) | 5 (2.2%) | 3.2% (−0.2 to 6.8) | 0.07 |

| All-cause mortality | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | −0.4% (−1.3 to 0.4) | 0.33 |

| Cardiac mortality | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0% (0.0 to 0.0) | 1.00 |

| Myocardial infarction* | 6 (2.7%) | 3 (1.3%) | 1.4% (−1.2 to 4.0) | 0.29 |

| Target-lesion revascularisation | 9 (4.1%) | 4 (1.8%) | 2.3% (−0.8 to 5.5) | 0.14 |

| Target-vessel revascularisation | 10 (4.6%) | 4 (1.8%) | 2.8% (−0.4 to 6.0) | 0.11 |

| Definite stent thrombosis | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (0.9%) | 0.0% (−1.7 to 1.8) | 0.97 |

| Events at 24 months† | Follow-up in 218 patients | Follow-up in 228 patients | HR(95% CI) | P value |

| MACE | 12.9% (28) | 8.4% (19) | 0.63 (0.35 to 1.13) | 0.12 |

| All-cause mortality | 2.3% (5) | 2.2% (5) | 0.94 (0.28 to 3.31) | 0.94 |

| Cardiac mortality | 0.9% (2) | 0.9% (2) | 0.96 (0.13 to 6.8) | 0.96 |

| Myocardial infarction* | 5.1% (11) | 3.1% (7) | 0.60 (0.23 to 1.55) | 0.30 |

| Target-lesion revascularisation | 9.2% (20) | 6.2% (14) | 0.66 (0.33 to 1.30) | 0.23 |

| Target-vessel revascularisation | 10.5% (23) | 6.6% (15) | 0.61 (0.32 to 1.17) | 0.13 |

| Risk difference (95% CI) | ||||

| CCS class ≥2 angina‡ | 8 (3.9%) | 9 (4.1%) | −0.2% (−4.0 to 3.4) | 0.89 |

| Stent thrombosis‡ | ||||

| Definite, any (0–2 years) | 3 (1.4%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0.1% (−2.0 to 2.2) | 0.96 |

| Definite, acute (0–1 day) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.0% (−1.2 to 1.3) | 0.98 |

| Definite, subacute (2–30 days) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.0% (−1.2 to 1.3) | 0.98 |

| Definite, late (1–12 months) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0% (0.0 to 0.0) | – |

| Definite, very late (12–24 months) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.0% (−1.2 to 1.3) | 0.98 |

| Definite or probable, any (0–2 years) | 4 (1.8%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0.5% (−1.7 to 2.8) | 0.66 |

| Definite, prob. or poss., any (0–2 years) | 6 (2.8%) | 5 (2.2%) | 0.6% (−2.3 to 3.4) | 0.70 |

*Non-procedure related. Values are n (%).

†Twenty-four month results are given as Kaplan-Meier estimates and (n).

‡Results are given as n (%), risk difference and 95% CI.

MACE, major adverse cardiac events.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analyses of the primary composite endpoint. Event rates are Kaplan-Meier estimates by time-to-event of the composite endpoint for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). The likelihood of interaction of the subgroup variable and allocated treatment is given by the p value for interaction. SB, side branch; DS%, diameter stenosis in %. Angiographic parameters are by visual estimation.

Discussion

Main findings

In the randomised Nordic-Baltic Bifurcation Study IV, treatment of bifurcation lesions involving a large SB resulted in 6-month MACE of 5.5% vs 2.2% and 2-year MACE of 13.2% vs 8.3%, both statistically non-significant, after treatment by the simple provisional SB stenting technique or planned two-stent techniques, respectively. Two-stent procedures were associated with less angiographic SB stenosis at 8-month follow-up but procedure time, fluoroscopy time, use of contrast and use of stents were all increased in the two-stent group.

One or two stents for bifurcations

The study addresses one of the main questions in coronary bifurcation treatment; routine stenting of both MV and SB or stenting of the MV only with optional SB treatment if reduced flow or a severe stenosis is detected after MV stent implantation. Earlier randomised clinical trials on simple versus complex bifurcation stenting, with the exception of the DKCRUSH-II study,9 were in favour of the simple one-stent strategy.4–7 19 In the BBC ONE study, there were more myocardial infarctions at 9 months in the two-stent group (3.6% vs 11.2%; p=0.001) driven by periprocedural biomarker elevation.2 In the 5-year follow-up in the Nordic-Baltic Bifurcation Study I, there was no statistically significant difference in MACE after simple versus complex strategies (15.8% vs 21.8%; p=0.12) but an indication of more favourable long-term results after simple stenting using first generation DES.3 In the DKCRUSH-II study, the double kissing crush two-stent technique reduced new revascularisations as compared with optional SB stenting at 5 years.20 However, in that study, the difference between the study groups was possibly influenced by a study-related angiographic follow-up, and the 1-year event rates in the two-stent group were numerically higher than in the one-stent group of Nordic-Baltic I and IV.

Compared with earlier studies, Nordic-Baltic IV was the first randomised study comparing one-stent versus two-stent strategies in bifurcations involving large SB (≥2.75 mm) with angiographic significant disease. Although our MACE rate was higher in the simple group (12.8%) compared with the complex group (8.3%), mostly driven by a statistically insignificant difference in target lesion revascularisation (9.2% vs 6.1%, p=0.23), we failed to document a significant advantage in the use of complex two-stent techniques. However, the numerically lower MACE rates do suggest that two-stent procedures were at least safe in the treatment of patients with significant SB disease.

Two-stent techniques

Our good results using two-stent techniques are in line with the DK-CRUSH II results.20 Still, the double kissing crush technique applied in the DK-CRUSH study series was later found to be superior to culotte stenting in patients with unprotected LMCA disease by the same group of investigators21 leading to the recent ESC recommendation of the double kissing crush technique for the treatment of Medina Class 1.1.1 distal LMCA bifurcation lesions.22 In Nordic-Baltic IV, applying predominantly the culotte and mini-crush techniques, the success rate of KBI was 92%, whereas the success rate of KBI using the double kissing crush technique was 96%–100% in the DK-CRUSH study series.8 17–19 KBI in culotte was successful in 96 of 97 cases in the 200 pts EBC TWO trial but still yielded similar outcome compared with provisional T stenting for large bifurcations.20 We do not know if the relatively favourable results in the two-stent group of Nordic-Baltic IV might have been further improved using the double kissing crush technique.

One-stent technique

In the provisional SB stenting group, the strict cross-over criteria resulted in SB stenting in only 3.7% of cases. The numerically increased rate of target lesion revascularisation suggests that some SBs might have been undertreated by relying solely on visual assessed diameter stenosis and reduction in TIMI flow for SB stenting. Large SBs may supply a larger territory and the increased rate of angiographic SB restenosis after simple stenting may indicate a clinical relevant difference between the two strategies. We were not able to demonstrate a significant difference for longer SB lesions >5 mm likely due to the small subsample. Still, the numerical difference (16.5% vs 9.6%) could indicate that longer lesions more often require SB stenting which would be in line with other reports.23 24 Previous studies on simple versus complex stenting documented a large variation, from 2% to 31%, in SB stenting using the simple optional SB stenting technique.2 6 9 10 25 Currently, the generally accepted criteria for SB intervention in coronary bifurcations are based on angiographic indication of reduced flow, stenosis severity >75% DS, and SB stenosis length >5 mm,26 but physiological measurements such as fractional flow reserve assessment27 or use of intravascular ultrasound28 and optical coherence tomography29 imaging techniques might improve our angiography-based decisions on indication for SB revascularisation.

In Nordic-Baltic IV, it was recommended to perform a ‘therapeutic predilation’ of the SB with a balloon sized according to the SB reference diameter. Pan et al demonstrated that a similar strategy reduced both the rate of SB TIMI flow <III and the need for subsequent KBI and the SB predilation did not impair SB rewiring.30 The SB predilation rate in Nordic-Baltic IV was 64%, and the total rate of SB balloon dilatation was 78%, leaving 22% in the simple one-stent group without any SB treatment. This lack of SB intervention might indicate a suboptimal treatment, although it is unknown if the SB in these patients was left with a functionally significant stenosis.

In Nordic-Baltic IV, the mean lesion length in the SB was 5.5 mm compared with 10 mm in the BBK study4 and 15 mm in the DKCRUSH II study.20 The longer SB lesions likely contributed to the higher rate of cross over to SB stenting in the simple groups in these studies of 19% and 28%, respectively. The authors of the present study believe that it makes little sense to randomise patients with long significant lesions in a large SB, in one-stent versus two-stent technique studies as such SB lesions may require stenting in any case.

The study was initiated before introduction and recommendation of the proximal optimisation technique (POT)31 to improve proximal stent apposition and facilitate wiring of a SB jailed by a stent.26 Despite the potential advantages of this additional procedural step,32–34 the clinical importance has yet to be fully determined35 and optimal execution clarified.36 It is therefore uncertain to which extent the lack of systematic postdilatation of the proximal segment negatively impacted our results, and if POT has different effects in simple and complex techniques.

Procedural complexity

The provisional stenting approach was performed using less contrast and less radiation in shorter procedures, as in previous studies.6 10 25 These procedural characteristics of the simple one-stent technique may be of considerable importance in selecting strategy, especially in high-risk and frail elderly patients. At the same time, the presented 2-year results by the two strategies do not contradict the choice of a two-stent strategy in selected cases with functional significant SB stenosis or in case of high risk of SB compromise, difficult SB access or anticipated difficult access after MV stent implantation.

Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy

The recommended duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was 12 months in Nordic-Baltic IV independent of treatment indication and complexity of treatment. The present ESC recommendation is 6 months DAPT after PCI indicated by stable angina pectoris with the provision that prolonged DAPT may be considered after complex PCI including two-stent bifurcation treatment.37 We cannot rule out a minor positive effect on outcomes for the two-stent group compared with patients treated with one-stent techniques at the expense of increased bleeding risk in both groups.38 Our results, however, indicate that such potential positive effect for two-stent techniques may be countered by using first generation DES in half of the patients in this trial. An individualised assessment of treatment complexity, treatment result and the patients perceived bleeding risk is recommended when determining the optimal duration of DAPT.37

First and newer generation DES

During the first half of enrolled patients, the first generation Cypher Select+ was used as stent, while the newer generation Xience stent was used as stent in the latter part. The equal results of Cypher and Xience in the simple group but more than 50% reduction in MACE in the complex group after treatment by newer generation stent compared with first-generation stents may indicate an improved safety of two-stent techniques using newer generation stents. This could indicate an important advancement in the safety of two-stent techniques that may be associated with increased mortality when performed with first-generation DES.19 The hypersensitive reaction induced in some patients by the polymer of first-generation stents39 may have been aggravated by higher strut density in overlapping40 and crushed stent segments, and the closed cell design might have limited the expansion of stents implanted through stent cells as in the culotte technique.41 The newer generation Xience stent features a more biocompatible polymer and open cell design and thus might provide a larger safety gain in two-stent techniques than in single stent techniques.42 43 It is possible that due to the favourable results in the complex group by second generation DES and the consistent documentation of double kissing crush as a superior two-stent technique, we might have underestimated the positive effect of the combination of best stent and best technique for two-stent treatment. On the other hand, less conservative SB intervention criteria might have reduced the rate of early target lesion revascularisation, although such more liberal SB treatment strategy during provisional stenting is not backed by published results. Recent guidelines recommend PCI for treatment of LMCA stenosis in patients with low (≤22) SYNTAX score.22 This has increased the focus on optimal bifurcation stenting as 80%–85% of LMCA treatments involve the distal LMCA bifurcation.44 45 In Nordic-Baltic IV, only a small portion of cases were treated for distal LMCA bifurcation stenosis. Thus, extrapolation of our results to this lesion subset should be done with caution given the specific technical challenges in distal LMCA bifurcation PCI.46

Study limitations

Enrolled patients had rather short SB lesions, thus limiting conclusions to this relevant subset of bifurcation lesions. The use of angiographic SB inclusion criteria might have led to inclusion of some patients with physiologically insignificant SB disease favouring the simple one-stent technique, and despite randomisation, the SB diameter stenosis before treatment was less severe in the simple group indicating a potentially lower overall risk in this group. The sample size estimate for Nordic-Baltic IV was based on the limited available evidence at time of conceptualisation and we cannot exclude that the study was underpowered to detect a true difference between the two treatment strategies. It was strongly recommended to perform only clinically driven and fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided revascularisation in the follow-up period but the planned 8-month angiographic follow-up might still have led to more revascularisation. The plateau of the MACE curves before the increase in revascularisation seen around the 8-month time point could also reflect that patients truly requiring revascularisation awaited the planned follow-up and some cases were treated before the patient would normally seek a doctor. As the safety of the techniques studied might change over time, the reported 2-year results added clinically relevant information to this report but very long-term follow-up is needed to make a final assessment of one versus two stents for coronary bifurcation treatment.

Conclusion

In the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions involving a large SB with ostial stenosis, routine stenting of both the MV and the SB did not improve outcome significantly compared with treatment by the simpler MV stenting technique after 2 years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jakob Hjort (Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark) for data-management assistance and Helle Bargsteen and Lars Peter Jørgensen (Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark) for data retrieval and verification. We highly appreciated the invaluable support from involved operators and staff at all participating institutions.

Footnotes

IK and NRH contributed equally.

Funding: Cordis Corp and Abbott Vascular supported the study equally by funding the pr. patient fee to participating centers.

Competing interests: IK received institutional research grants from Cordis, Abbott and speaker fee from Astra Zeneca. NRH has received institutional research grants from Cordis, Abbott, Terumo, Biosensors, Biotronik, Medis medical imaging, Reva Medical, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical and Medtronic and has received speaker fees and personal honorarium from St. Jude Medical, Terumo, Reva Medical and Biotronik. LOJ has received institutional research grants from Terumo, Biosensors and Biotronik. JFL has received institutional research grants from Cordis, Abbott, Terumo, Biosensors, Biotronik, Medis medical imaging, Reva Medical, Boston Scientific, Heartflow, St. Jude Medical and Medtronic and has received speaker fees from Biotronik, Biosensors, Tryton, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, Terumo, Reva medical, Cordis, Astra Zeneca and Abbott. GL has received speaker fees from Astra Zeneca.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the national or local medical ethics committees and was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01496638.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data will not be made available.

References

- 1. Nakazawa G, Yazdani SK, Finn AV, et al. Pathological findings at bifurcation lesions: the impact of flow distribution on atherosclerosis and arterial healing after stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1679–87. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hildick-Smith D, de Belder AJ, Cooter N, et al. Randomized trial of simple versus complex drug-eluting stenting for bifurcation lesions: the British bifurcation coronary study: old, new, and evolving strategies. Circulation 2010;121:1235–43. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.888297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maeng M, Holm NR, Erglis A, et al. Long-Term results after simple versus complex stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:30–4. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferenc M, Ayoub M, Büttner H-J, et al. Long-Term outcomes of routine versus provisional T-stenting for de novo coronary bifurcation lesions: five-year results of the bifurcations bad Krozingen I study. EuroIntervention 2015;11:856–9. 10.4244/EIJV11I8A175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pan M, de Lezo JS, Medina A, et al. Rapamycin-eluting stents for the treatment of bifurcated coronary lesions: a randomized comparison of a simple versus complex strategy. Am Heart J 2004;148:857–64. 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colombo A, Bramucci E, Saccà S, et al. Randomized study of the crush technique versus provisional side-branch stenting in true coronary bifurcations: the cactus (coronary bifurcations: application of the crushing technique using sirolimus-eluting stents) study. Circulation 2009;119:71–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Généreux P, Kumsars I, Lesiak M, et al. A randomized trial of a dedicated bifurcation stent versus provisional stenting in the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:533–43. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hildick-Smith D, Behan MW, Lassen JF, et al. The EBC two study (European bifurcation coronary two): a randomized comparison of provisional T-Stenting versus a systematic 2 stent Culotte strategy in large caliber true bifurcations. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen S-L, Santoso T, Zhang J-J, et al. A randomized clinical study comparing double kissing crush with provisional stenting for treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions: results from the DKCRUSH-II (double kissing crush versus provisional stenting technique for treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:914–20. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steigen TK, Maeng M, Wiseth R, et al. Randomized study on simple versus complex stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions: the Nordic bifurcation study. Circulation 2006;114:1955–61. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Medina A, Suárez de Lezo J, Pan M. A new classification of coronary bifurcation lesions. Revista Española de Cardiología 2006;59 10.1016/S1885-5857(06)60130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carrie D, Karouny E, Chouairi S, et al. "T"-shaped stent placement: a technique for the treatment of dissected bifurcation lesions. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1996;37:311–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chevalier B, Glatt B, Royer T, et al. Placement of coronary stents in bifurcation lesions by the "culotte" technique. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:943–9. 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00510-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sheiban I, Albiero R, Marsico F, et al. Immediate and long-term results of "T" stenting for bifurcation coronary lesions. Am J Cardiol 2000;85:1141–4. 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)00712-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharma SK, Choudhury A, Lee J, et al. Simultaneous kissing stents (sks) technique for treating bifurcation lesions in medium-to-large size coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol 2004;94:913–7. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2525–38. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation 2007;115:2344–51. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holm NR, Højdahl H, Lassen JF, et al. Quantitative coronary analysis in the Nordic bifurcation studies. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;27:175–80. 10.1007/s10554-010-9715-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Behan MW, Holm NR, de Belder AJ, et al. Coronary bifurcation lesions treated with simple or complex stenting: 5-year survival from patient-level pooled analysis of the Nordic bifurcation study and the British bifurcation coronary study. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1923–8. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen S-L, Santoso T, Zhang J-J, et al. Clinical outcome of double kissing crush versus provisional stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions: the 5-year follow-up results from a randomized and multicenter DKCRUSH-II study (randomized study on double kissing crush technique versus provisional stenting technique for coronary artery bifurcation lesions). Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10:e004497 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.116.004497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen S-L, Xu B, Han Y-L, et al. Clinical outcome after DK crush versus Culotte stenting of distal left main bifurcation lesions: the 3-year follow-up results of the DKCRUSH-III study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:1335–42. 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neumann F-J, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J 2019;40:87–165. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hahn J-Y, Chun WJ, Kim J-H, et al. Predictors and outcomes of side branch occlusion after main vessel stenting in coronary bifurcation lesions: results from the COBIS II registry (coronary bifurcation stenting). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1654–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zimarino M, Briguori C, Amat-Santos IJ, et al. Mid-Term outcomes after percutaneous interventions in coronary bifurcations. Int J Cardiol 2019;283:78–83. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.11.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferenc M, Gick M, Kienzle R-P, et al. Randomized trial on routine vs. provisional T-stenting in the treatment of de novo coronary bifurcation lesions. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2859–67. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lassen JF, Burzotta F, Banning AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for the left main stem and other bifurcation lesions: 12th consensus document from the European bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention 2018;13:1540–53. 10.4244/EIJ-D-17-00622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kang S-J, Ahn J-M, Kim W-J, et al. Functional and morphological assessment of side branch after left main coronary artery bifurcation stenting with cross-over technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2014;83:545–52. 10.1002/ccd.25057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kang S-J, Kim W-J, Lee J-Y, et al. Hemodynamic impact of changes in bifurcation geometry after single-stent cross-over technique assessed by intravascular ultrasound and fractional flow reserve. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2013;82:1075–82. 10.1002/ccd.24956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Watanabe M, Uemura S, Sugawara Y, et al. Side branch complication after a single-stent crossover technique: prediction with frequency domain optical coherence tomography. Coron Artery Dis 2014;25:321–9. 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pan M, Medina A, Romero M, et al. Assessment of side branch predilation before a provisional T-stent strategy for bifurcation lesions. A randomized trial. Am Heart J 2014;168:374–80. 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stankovic G, Darremont O, Ferenc M, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for bifurcation lesions: 2008 consensus document from the fourth meeting of the European bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention 2009;5:39–49. 10.4244/EIJV5I1A8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Foin N, Secco G, Ghilencea L, et al. Final proximal post-dilatation is necessary after kissing balloon in bifurcation stenting. EuroIntervention 2011;7:597–604. 10.4244/EIJV7I5A96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dérimay F, Rioufol G, Cellier G, et al. Benefits of final proximal optimization technique (POT) in provisional stenting. Int J Cardiol 2019;274:71–3. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hakim D, Chatterjee A, Alli O, et al. Role of proximal optimization technique guided by intravascular ultrasound on stent expansion, stent symmetry index, and side-branch hemodynamics in patients with coronary bifurcation lesions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.117.005535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rigatelli G, Zuin M, Karamfilof K, et al. Impact of different final optimization techniques on long-term clinical outcomes of left main cross-over stenting. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2019;20:108–12. 10.1016/j.carrev.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Holm NR, Andreasen LN, Christiansen EH. Keep bifurcation stenting simple and cheap or controlled and optimised? EuroIntervention 2018;13:e1741–3. 10.4244/EIJV13I15A282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the task force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of cardiology (ESC) and of the European association for Cardio-Thoracic surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2018;39:213–60. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Giustino G, Chieffo A, Palmerini T, et al. Efficacy and safety of dual antiplatelet therapy after complex PCI. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1851–64. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.07.760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, et al. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:193–202. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Finn AV, Kolodgie FD, Harnek J, et al. Differential response of delayed healing and persistent inflammation at sites of overlapping sirolimus- or paclitaxel-eluting stents. Circulation 2005;112:270–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.508937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murasato Y, Hikichi Y, Horiuchi M. Examination of stent deformation and gap formation after complex stenting of left main coronary artery bifurcations using microfocus computed tomography. J Interv Cardiol 2009;22:135–44. 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2009.00436.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Terashita D, Otake H, Shinke T, et al. Differences in vessel healing between Sirolimus- and everolimus-eluting stent implantation for bifurcation lesions: the J-REVERSE optical coherence tomography substudy. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:384–90. 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hermiller JB, Applegate RJ, Baird C, et al. Clinical outcomes in real-world patients with bifurcation lesions receiving Xience V everolimus-eluting stents: four-year results from the Xience V USA study. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent 2016;88:62–70. 10.1002/ccd.26217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stone GW, Sabik JF, Serruys PW, et al. Everolimus-Eluting stents or bypass surgery for left main coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2223–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1610227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mäkikallio T, Holm NR, Lindsay M, et al. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty versus coronary artery bypass grafting in treatment of unprotected left main stenosis (noble): a prospective, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016;388:2743–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32052-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Burzotta F, Lassen JF, Banning AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in left main coronary artery disease: the 13th consensus document from the European bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention 2018;14:112–20. 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]