Abstract

We systematically reviewed all published cases of zygomycosis, an increasingly important infection with high mortality, in neonates. We searched PubMed and individual references for English publications of single cases or case series of neonatal (0 to 1 month) zygomycosis. Cases were included if they fulfilled prespecified criteria. Fifty-nine cases were published through July 2007. Most of the infants (77%) were premature. The most common sites of zygomycosis were gastrointestinal (54%) and cutaneous (36%) diseases. This pattern differs from sinopulmonary and rhinocerebral patterns of older children. Fifty-six percent of cases were diagnosed by histology only and 44% by histology and culture. Rhizopus spp. were isolated from 18/25 (72%) cases. Thirty-seven percent of patients received no antifungal therapy. Thirty-two (54%) neonates underwent surgery with (39%) or without (15%) antifungal agents. Overall mortality was 64%. A higher fraction of neonates treated with amphotericin B and surgery survived than those who received no therapy (70% versus 5%). Zygomycosis is a life-threatening infection in neonates with a distinct pattern of gastrointestinal and cutaneous involvement and high mortality. Combination of amphotericin B and surgery was common management strategy in survivors.

Keywords: Epidemiology, mucormycosis, outcome, Rhizopus spp., gastrointestinal infection

Neonates, especially those born prematurely, have important deficiencies in their innate immune response, leading to increased susceptibility to opportunistic bacteria and fungi.1 Although Candida spp. are the most frequent fungi causing invasive infection in neonates,2 filamentous fungi may also cause infections that can be life-threatening.3

Zygomycosis refers to a group of uncommon but frequently fatal mycoses caused by fungi of the class Zygomycetes.4 These include human pathogens from classes of both Mucorales and Entomophthorales. Zygomycosis has emerged as an increasingly important fungal infection during the past decade. This increase has been particularly evident in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients and patients with hematologic malignancies.5 Other populations at risk for zygomycosis include patients with diabetes, burns, and trauma as well as those undergoing surgery or deferoxamine therapy. Neonates also have been described in individual case reports as a population at risk for zygomycosis.6–8

To date, however, there has not been a comprehensive review of zygomycosis in neonates to guide our understanding of the epidemiology, management, and outcome of this devastating infection. We therefore systematically reviewed the English-language literature for all cases of neonatal zygomycosis. In this review, we sought to describe demographic and clinical characteristics as well as outcome of invasive zygomycosis in neonates and to compare them with those of older children and adults.9,10 This may lead to improvement of management of neonatal invasive zygomycosis.

METHODS

Literature Search

Case reports and series of neonatal zygomycosis published in the English literature were retrieved by use of “zygomycosis,” “mucormycosis,” “phycomycosis,” “Rhizopus,” “Mucor,” “Rhizomucor,” “Cunninghamella,” “Absidia,” “Apophysomyces,” “Syncephalastrum,” “Sakse-naea,” “Cokeromyces,” “Entomophthoral,” “Conidiobolus,” and “Basidiobolus” as keywords with the limitation “less than 1 month of age” in searches of the PubMed bibliographic database (U.S. National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD) from 1950 through July 2007. After this initial series of reports was reviewed, the references cited in the above articles were screened for additional cases of neonatal zygomycosis. In addition, all references from major book chapters written on the subject of zygomycosis were reviewed. Their references were carefully scrutinized for single case reports or case series.

Criteria for Inclusion of Cases

Only those cases that contained the following five variables were included in our review:

Age: Cases of patients less than 1 month of age were included.

Documentation of infection: Zygomycosis was confirmed either histologically or by culture. Information as to whether the infection was documented premortem or postmortem also was required.

Anatomic location of infection: Documentation of the primary site of infection at time of diagnosis and whether the infection remained localized or disseminated was required. Disseminated infection was defined as two or more noncontiguous sites. Those patients with disseminated infection at the time of diagnosis where the primary site of infection was impossible to identify were classified as having “generalized disseminated” infection. Patients with cutaneous infection were subcategorized into three groups. Those patients in whom the infection was confined to the cutaneous or subcutaneous tissue were defined as having localized disease. Patients with invasion into muscle, tendon, or bone were classified as “deep extension.” Patients with cutaneous disease involving another noncontiguous site were considered disseminated. Patients with pulmonary infection were subcategorized in a similar manner. Those with disease confined to the lungs were classified as localized. Those with disease that extended to the chest wall, pulmonary artery, aorta, or heart were considered “deep extension.” Those cases that demonstrated involvement of a noncontiguous site were classified as disseminated.

Therapeutic intervention: Only those cases that specified presence or absence of both surgery and antifungal therapy were included.

Outcome: Mortality was assessed as “all-cause mortality” during the course of zygomycosis.

Database Development

Filemaker Pro 5.5 software (Santa Clara, CA) was used to develop an initial database of categorical and continuous variables. The categorical variables included gender, underlying diagnosis, organism, diagnostic method used for recovery of organism, premortem or postmortem diagnosis, infection site (focal or disseminated disease), surgery, and outcome. The continuous variables included year of diagnosis, year of publication, gestational age, birth weight, postnatal age of patient, and dose/duration of antifungal therapy. From there, the data were transferred to a Microsoft Excel (XP Professional) software (Redmond, WA) for further analysis and presentation.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (version 11.5; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Categorical variables are reported as percentages and continuous variables (except for years of diagnosis and publication) as median and interquartile range (IQR).

RESULTS

Fifty-nine cases of zygomycosis were identified in neonates.6–8,11–51 The main demographic, clinical, therapeutic, and outcome data of these cases are shown in Table 1. The earliest case of neonatal zygomycosis included in this study was published in 1956.51 There was a clear increase in the number of neonatal zygomycosis cases reported over time, with 71% of all cases published after 1990 (Table 2). Although the mortality of reported zygomycosis cases remained high through the years of reporting, there were fewer deaths in cases published after 2000 (41%) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Cases of Neonatal Zygomycosis Published

| Year and Reference | Sex/Age (d) | GA (wk) | BW (g) | Factors Preceding Zygomycosis | Sites of Infection (Extension) | Organism and Method | Treatment (Duration, d)† | Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroids | Antb | Surgery | Other Risk Factors* | ||||||||

| 195651 | M/20 | 2830 | Yes | No | Malnutrition | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No | ||

| 195950 | F/4 | Yes | No | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No | ||||

| 196049 | M/6 | <38 | Yes | No | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No | |||

| 196048 | M/9 | <38 | 3175 | Yes | No | Gl (L) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No | ||

| 196141 | M/9 | 1360 | Yes | No | Gl (L) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No | |||

| 196141,44 | F/10 | 3200 | No | No | Malnutrition, diarrhea, acidosis | Gl (L) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No | ||

| 196747 | M/15 | 1250 | No | Diarrhea | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No | |||

| 1980/’7737 | M/5 | 32 | No | Yes | Yes | Gastric trauma, colonized bandage | CU (DE) | R. oryzae, T & C | AMB-D (10) & surgery | Yes | |

| 198039 | M/7 | 32 | 2560 | Yes | Yes | Nasogastric intubation | Gl (D) | R. oryzae, T & C | AMB-D (14) & surgery | Yes | |

| 198035 | M/31 | ≥38 | 3200 | No | Yes | No | Palate, maxilla, orbit, CE (D) | Zygomycete, T | AMB-D (7) & surgery | Yes | |

| 198111 | M/11 | 1600 | No | Yes | Yes | Acidosis | CU (D) | Zygomycete, T & C (postmortem) | None | No | |

| 198443 | F/11 | 25 | 910 | No | Yes | No | Acidosis, ↑GIu, renal insufficiency | CU & PU (D) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No |

| 1986/’5221 | F/28 | ≥38 | No | No | No | PU (D) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No | ||

| 1986/’5821 | M/4 | ≥38 | No | Yes | Gl (L) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | Surgery | No | |||

| 1986/’8121 | M/30 | ≥38 | No | Yes | CU (L) | Zygomycete, T | None | Yes | |||

| 198942 | F/9 | ≥38 | No | No | Diarrhea, acidosis | RC (L) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No | ||

| 198915 | M/15 | 26 | 1100 | Yes | No | Acidosis, prolonged adhesive strapping | CU (L) | Rhizopus spp., T & C | AMB-D & 5FC (28) & surgery | Yes | |

| 199013 | M/16 | 430 | Yes | No | Metabolic disorder, nasogastric tube | Gl (D) | Rhizopus spp., T & C | AMB-D (51) & surgery | No | ||

| 199234 | M/neonate | No | Yes | PU, MO (D) | Rhizopus spp., T & C (postmortem) | None | No | ||||

| 199220 | F/21 | 27 | 1190 | Yes | No | Yes | Gl (D) | R. microsporus, T & C | Surgery | No | |

| 199220 | F/21 | 24 | 660 | Yes | No | Yes | Gl (L) | Zygomycete, T | Surgery | No | |

| 199311 | F/26 | 38 | No | Yes | No | Gl (L) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No | ||

| 199438 | M/5 | 28 | 1131 | No | Yes | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T | Surgery | No | ||

| 199414 | M/16 | 28 | 1245 | Yes | Yes | No | Colonized adhesive to endotracheal tube | CU (D) | R. arrhizus, T & C | AMB-D & rifampicin (5) & surgery | No |

| 199418 | M/20 | 26 | Yes | No | Gl (D) | Mucor spp., T&C | None | No | |||

| 199546 | M/9 | ≥38 | 2365 | No | No | Yes | Early feeding | Gl (L) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No |

| 199546 | M/9 | 29 | 1080 | No | Yes | No | Early feeding | Limb, part of abdomen, Gl, kidney, ureter, thrombus in aorta (D) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No |

| 199546 | F/1 | 36 | 1980 | No | Yes | Yes | Early feeding | Gl (L) | Rhizopus spp., T& microscopy | AMB-D (15) & surgery | Yes |

| 199517 | F/24 | 26 | 670 | Yes | No | No | Hyperglycemia | CU (DE) | Rhizopus spp., T&C | AMB-D (51) & surgery | Yes |

| 199616 | F/4 | 24 | 680 | Yes | Yes | No | Wooden tongue depressors | CU (L) | R. microsporus, T&C | LAMB & ITC (23) | Yes |

| 199616 | F/7 | 25 | 525 | No | Yes | No | Wooden tongue depressors | CU (D) | R. microsporus, T&C | LAMB & ITC (2) | No |

| 199616 | F/20 | 25 | 750 | Yes | Yes | No | Wooden tongue depressors | CU (DE) | R. microsporus, T&C | LAMB & ITC (14) & surgery | Yes |

| 199616 | M/22 | 25 | 850 | Yes | Yes | No | Wooden tongue depressors | CU (D) | R. microsporus, T&C | LAMB & ITC (2) | No |

| 19976 | M/8 | 24 | 430 | Yes | Yes | No | Monitor lead | CU (D) | Rhizopus spp., T&C (postmortem) | None | No |

| 199740 | M/8 | 35 | 1100 | Yes | Yes | No | Sepsis, renal failure, ↑Glu, suspected HIV infection | CU (DE) | Zygomycete, T (postmortem) | None | No |

| 199733 | 9 | 29 | 1380 | Yes | No | Impaired immunity | Gl (D) | Rhizomucor spp., T & C | AMB-D (49) & surgery | Yes | |

| 199812 | F/14 | 31 | 1500 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Umbilical catheter | CU (D) | Absidia corymbifera, T & C | AMB-D (14) & surgery | No |

| 199819 | M/21 | 26 | 915 | Yes | No | No | Adhesive tape | CU (DE) | R. oryzae, T & C | AMB-D (16) | Yes |

| 199812 | M/25 | ≥38 | Yes | No | Several chest tubes | PU (L) | A. corymbifera, T & C | None | No | ||

| 199832 | F/9 | No | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T postmortem) | None | No | |||||

| 199832 | F/4 | No | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T | Surgery | No | |||||

| 199931 | F/11 | 24 | 730 | Yes | No | Gl (D) | R. microsporus, T & C | AMB-D (4) & surgery | No | ||

| 200130 | M/19 | 34 | 1810 | Yes | No | Acidosis, nasogastric tube | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T | AMB-D (32) & surgery | No | |

| 200229 | F/12 | 37 | 3650 | Yes | Yes | No | IV catheter | CU (L) | Rhizopus arrhizus, T & C | AMB-D (2) & surgery | No |

| 200229 | F/14 | 25 | 635 | Yes | No | IV catheter | CU (L) | Rhizopus spp., T & C | AMB-D & surgery | Yes | |

| 200327 | M/15 | 25 | 820 | Yes | Yes | No | Infection site: IV site | CU (L) | Zygomycete, T | AMB-D (19) & surgery | Yes |

| 200328 | F/17 | 24 | 740 | Yes | Yes | No | Hyperglycemia | CU (L) | A. corymbifera, T & C | AMB-D (14) & surgery | Yes |

| 20047 | F/12 | 25 | 704 | Yes | No | Acidosis, hyperglycemia, nasogastric tube | Gl (D) | A. corymbifera, T & C | LAMB (29) | No | |

| 200425 | F/15 | 32 | 2944 | Yes | Yes | No | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T & immunostaining | Surgery | Yes | |

| 20048 | F/27 | 36 | 1600 | No | Yes | No | Containment mesh-associated surgical wound | CU (L) | A. corymbifera, T & C | AMB-D (28) & surgery | Yes |

| 200426 | M/15 | 26 | 839 | Yes | Yes | No | Nasogastric tube, intubation | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T | AMB-D (42) & surgery | Yes |

| 200523 | M/10 | 35 | 1600 | Yes | No | CU (L) | Zygomycete, T & C | AMB-D (90) & surgery | Yes | ||

| 200524 | M/4 | SGA | No | No | Barium enema | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T | AMB-D (14) & surgery | No | ||

| 200524 | F/7 | ≥38 | No | No | Barium enema | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T | FLC & surgery | Yes | ||

| 200524 | M/16 | ≥38 | Yes | No | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T | None | No | |||

| 200622 | M/3 | 34 | 2000 | Yes | Yes | No | CU (L) | Zygomycete, T | AMB-D & surgery | Yes | |

| 200636 | F/4 | 30 | 1380 | Yes | No | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T | Surgery | No | ||

| 200636 | M/2 | 33 | 1710 | Yes | No | Gl (D) | Zygomycete, T | Surgery | No | ||

| 200745 | M/16 | ≥38 | 3200 | No | No | No | Gl (L) | Zygomycete, T | Surgery | Yes | |

Other risk factors as indicated by the authors in each case.

BW, body weight; Glu, glucose; 5FC, 5-flucytosine; FLC, fluconazole; IV, intravenous; R. oryzae, Rhizopus oryzae; R. arrhizus, Rhizopus arrhizus’, R. microsporus, Rhizopus microsporus T, tissue; C, culture; SGA, small-for-gestational-age infant; CU, cutaneous; Gl, gastrointestinal; RC, rhinocerebral; PU, pulmonary; MO, multiple organs; CE, cerebral; Antb, antibiotics; AMB-D, amphotericin B deoxycholate; LAMB, liposomal amphotericin B; DE, deep extension; D, disseminated; L, localized.

Table 2.

Published Cases of Neonatal Zygomycosis since 1950 through July 2007

| Time of Publication | All Patients Reported, n (%) | Reported Patients Who Died, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1950–1959 | 2 (3) | 2 (100) |

| 1960–1969 | 5 (8) | 5 (100) |

| 1970–1979 | 0 (0) | — |

| 1980–1989 | 10 (17) | 5 (50) |

| 1990–1999 | 25 (42) | 19 (76) |

| 2000-July 2007 | 17 (29) | 7 (41) |

| Total | 59 (100) | 38 (64) |

The demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients are depicted in Table 3. Male infants had a median age 10 days (IQR, 8 to 16) and female infants 14 days (IQR, 9 to 20.5). Most of the neonates (77%) were born prematurely (gestational age <38 weeks). Zygomycosis developed in the setting of several conditions that may have increased risk of zygomycosis. These included prior administration of corticosteroids or antibiotics or prior surgery as well as extremity immobilization with wooden tongue depressors, intravenous catheter sites, acidosis, and hyperglycemia. However, none of them was found to lead to more deaths due to zygomycosis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics, Potential Risk Factors, and Disease Patterns in Reported Cases of Neonates with Zygomycosis

| Characteristic | All Patients Reported, n (%) | Reported Patients Who Died, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | 59 (100) | 38 (64) |

| Demographics | ||

| Male gender | 33 (57) | 22 (67) |

| Female gender | 25 (43) | 16 (64) |

| GA in wk, median (IQR) | 28 (25–39) | 28 (25–34) |

| BW in g, median (IQR) | 1131 (745–1895) | 1131 (730–1710) |

| Postnatal age in d, median (IQR) | 12 (8–18) | 11.5 ± 1.3 (2–22) |

| Potential risk factors for death | ||

| Prematurity (<38 wk) | 37/48 (77) | 20/37 (54) |

| Corticosteroids | 18/34 (53) | 8/18 (44) |

| Antibiotics | 41/53 (77) | 25/41 (61) |

| Major surgery prior to the infection | 12/57 (21) | 8/12 (67) |

| Impaired host defense* | 3 | 2/3 (67) |

| Metabolic acidosis | 7 | 6/7 (86) |

| Contaminated source† | 20 | 10/20 (50) |

| Hyperglycemia | 5 | 3/5 (60) |

| Disease pattern | ||

| GI tract | 32 (54) | 25/32 (78) |

| Cutaneous | 21 (36) | 8/21 (38) |

| Pulmonary‡ | 4 (7) | 4/4 (100) |

| Rhino-orbital-cerebral | 2 (3) | 1/2 (50) |

| Extension of disease | ||

| Localized | 21 (36) | 10/21 (48) |

| Deeply extensive | 5 (8) | 1/5 (20) |

| Disseminated | 33 (56) | 28/33 (85) |

Other than corticosteroid treatment.

Wooden tongue depressors, intravenous catheter sites, etc.

One case with concomitant cutaneous infection; one case disseminated to multiple organs.

GA, gestationalage; BW, body weight, IQR, interquartile range; GI, gastrointestinal.

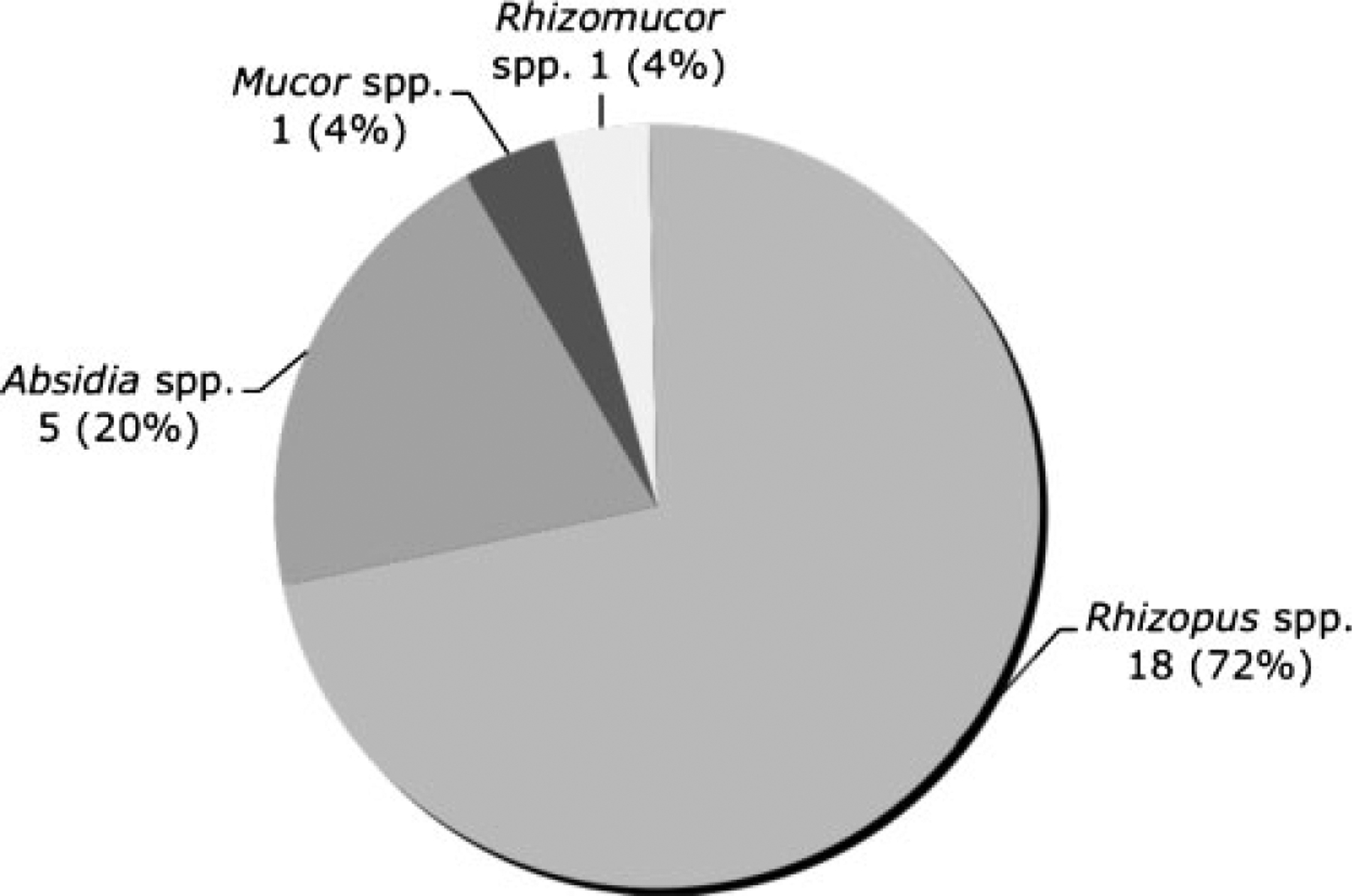

All neonates had infection documented by histopathology and/or culture. Thirty-three (56%) cases were diagnosed by means of histopathology only and 26 (44%) by histopathology and culture. The great majority of cases up to 1990 were diagnosed postmortem. The genera identified by culture are depicted in Fig. 1. Rhizopus spp. was by far the most frequent genus of Zygomycetes isolated. Among 16 isolates with species identification reported, six were identified as Rhizopus microsporus, five as Rhizopus oryzae/arrhizus, and five as Absidia corymbifera.

Figure 1.

Zygomycete genus identification by culture in neonates with zygomycosis.

The distribution of infection sites is shown in Table 3. The most common patterns of zygomycosis in neonates were gastrointestinal (GI; 52%) and cutaneous (36%) forms. Pulmonary and rhinocerebral infections as well as infections of other sites were found in a total of 6 (10%) cases. Localized disease was present in 36% of patients, deeply extensive disease in 8%, and disseminated disease in 56% of them (Table 3).

Among the 59 patients with zygomycosis, there were 38 (64%) deaths reported. Reported mortality was lower (38%) for cutaneous disease than for all the other forms of zygomycosis (> 66%). This was especially high in neonates who developed GI disease (the most frequent form reported), in which mortality was 78%. Of reported cases of disseminated disease 85% died (Table 3).

Twenty-two (37%) neonates did not receive any form of therapy (Table 4). Of the 28 neonates who received antifungal agents, 27 received amphotericin B (22 deoxycholate amphotericin B, five liposomal ampohotericin B). Among the patients who received antifungal treatment, four received amphotericin B in combination with itraconazole and one with flucytosine. The median duration of antifungal treatment was 14 (IQR, 8.5 to 28.5) days. Twenty-three (39%) patients underwent surgery in combination with antifungal chemotherapy, and 9 (15%) underwent surgery without antifungal agents.

Table 4.

Treatment and Outcome of Reported Cases of Neonatal Zygomycosis

| Treatment | All Patients Reported, n (%) | Reported Patients Who Died, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total of patients | 59 (100) | 38 (64) |

| Surgery combined with antifungal chemotherapy | 23 (39) | 7 (30) |

| Surgery alone | 9 (15) | 7 (78) |

| Antifungal chemotherapy alone | 5 (8) | 3 (60) |

| No therapy | 22 (37) | 21 (95) |

| Antifungal agents | ||

| AMB-D | 20 | 6 |

| LAMB | 1 | 1 |

| LAMB + itraconazole | 4 | 2 |

| AMB-D + flucytosine | 1 | 0 |

| AMB-D + rifampicin | 1 | 1 |

| Fluconazole | 1 | 0 |

AMB-D, amphotericin B deoxycholate; LAMB, liposomalamphoter-icin B.

Although neonates with no therapy showed a mortality of 95%, those who underwent surgery and were treated with antifungal agents had the lowest reported mortality (30%). Thirty-two neonates underwent surgery alone or as part of their treatment and 14 (56%) survived. Both cutaneous (13/21, 62%) and GI (17/31, 55%) zygomycosis cases were frequently treated with surgery. Among neonates who underwent surgery, 10/13 (77%) neonates with cutaneous infections survived, whereas only 7/18 (39%) neonates with GI infections survived.

DISCUSSION

This is the first reported comprehensive analysis of zygomycosis in neonates. This study underscores that prematurity is a distinctive underlying condition in developing zygomycosis independent of the well-known classical risk factors such as diabetes mellitus and hematologic malignancies. GI, disseminated, and cutaneous diseases appear to occur more often in neonates compared with older patients. Mortality is high especially for GI infections.

Of all cases of zygomycosis reported in the different age groups, GI zygomycosis is more commonly encountered in neonates than in pediatric patients and adults. Thus, among a total of 59 cases of zygomycosis reported in neonates, 32 (54%) were GI cases as compared with 17/124 (14%) of pediatric patients beyond age of 1 month and 33/772 (4%) of all patients above 18 years.9,10 Most of the cases of GI disease happened in premature babies, some occurring in association with progressive necrotizing skin lesions,6 some of them even mimicking the presentation of necrotizing enterocolitis only without the pathognomonic sign of pneumatosis intestinalis.52 Furthermore, although ileum and large bowel are by far the most frequently involved sites in necrotizing enterocolitis,52 a more extensive involvement of the GI tract from esophagus to large bowel may be observed in premature neonates with either disease.20,39

The mortality of GI zygomycosis was high, particularly in premature neonates (24/31, 77%) perhaps due to the delay in diagnosis and the underlying immunodeficiency of these babies.1 Although patients with cutaneous zygomycosis were similarly managed with surgical resection, GI infection still carried a worse postoperative prognosis. There was a tendency that, in contrast to cutaneous zygomycosis, performance of surgery did not appear to increase survival among patients with GI zygomycosis. Exploratory laparotomy and bowel resection was performed in 18 patients, and 11 (61%) of them died. Despite resection of infected bowel, the histopathologic diagnosis of zygomycosis was considerably delayed postoperatively. An increased awareness of this pattern of zygomycosis among neo-natologists is needed to facilitate timely diagnosis and management. In virtually all cases, the preoperative diagnosis was necrotizing enterocolitis. GI zygomycosis should be considered as an uncommon cause of disease in infants who present with signs of necrotizing enterocolitis. A tissue biopsy specimen should be obtained to diagnose these right-angle-branched, nonseptated hyphae, and specific culture should be performed.

Similarly, of all cases of zygomycosis reported in the different age groups, disseminated zygomycosis is more commonly encountered in neonates than in pediatric patients and adults. Specifically, among a total of 59 cases of zygomycosis in neonates, 33 (56%) cases were disseminated as compared with 16/124 (13%) cases in pediatric patients beyond age of 1 month and 164/772 (21%) cases among all patients above 18 years.9,10 Thus, neonates are most vulnerable to dissemination of zygomycosis, and early diagnosis and attempt to treat this devastating disease are very important.

Overall mortality of zygomycosis in neonates is 38/59 (64%) as compared with 70/124 (56%) for pediatric patients >1 month to 18 years9 and 408/772 (53%) for adults above 18 years.10 In a previous analysis of all pediatric patients including neonates up to 2003, disseminated infection and young age (< 12 months) were found to be independent risk factors of increased mortality as compared with localized disease and older age, respectively.9 This trend may be due to the high incidence of prematurity among neonates, other host differences that make zygomycosis more likely to be fatal in these patients, or other age-dependent differences in difficulties in diagnosis, management, and reporting of zygomycosis in pediatric and adult patients.

Amphotericin B continues to be the mainstay of medical treatment for both suspected and proven zygomycosis and most other invasive fungal infections in neonates. Deoxycholate amphotericin B appears to be well tolerated without significant nephrotoxicity in most neonates.3,53 The lipid formulations of amphotericin B were introduced for clinical care in the mid-1990s. Among newer antifungal agents, such as voriconazole, posaconazole, and echinocandins, with activity against filamentous fungi, posaconazole appears to have greater activity against Zygomycetes54; however, the pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy of posaconazole are not known in neonates.55

Because of the nature of the systematic reviews of reported cases as case reports or small series of cases, our results may be biased if the included cases are a biased sample of cases. Our review, however, is descriptive and summarizes the experience of a rare disease for which no large studies have been published, and therefore it is hoped to be helpful in better understanding this life-threatening infection. Future approaches to study this devastating and rarely diagnosed disease that is likely to be often missed could involve large research networks or clinical databases to prospectively collect incidence information. In addition, other studies could prospectively examine all necrotizing skin lesions and/or all medical (stool culture) and surgical necrotizing enterocolitis cases (biopsy) over a specified time period (1 to 2 years).

In this study, we included only infants up to 1 month of life. Because it was possible that there may be cases of zygomycosis in infants who had stayed in the NICU for time longer than 1 month, we also searched PubMed for any additional cases in young infants up to 3 months of age. There were no more cases that we could find according to our prespecified criteria. Thus, to be consistent with our neonatal terminology, we restricted our analysis to the infants up to 1 month of age. It seems that there are only few cases reported during infancy beyond neonatal age.56,57

The results of this comprehensive review of published neonatal cases of zygomycosis demonstrate that neonatal zygomycosis has a high mortality and strong propensity to disseminate. Early diagnosis and amphotericin B formulations combined with surgery may improve the otherwise dismal outcome.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levy O. Innate immunity of the newborn: basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Nat Rev Immunol 2007;7:379–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marodi L, Johnston RB Jr. Invasive Candida species disease in infants and children: occurrence, risk factors, management, and innate host defense mechanisms. Curr Opin Pediatr 2007;19:693–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groll AH, Jaeger G, Allendorf A, et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a critically ill neonate: case report and review of invasive aspergillosis during the first 3 months of life. [see comments] Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:437–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000;13:236–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kontoyiannis DP, Lionakis MS, Lewis RE, et al. Zygomycosis in a tertiary-care cancer center in the era of Aspergillus-active antifungal therapy: a case-control observational study of 27 recent cases. J Infect Dis 2005;191:1350–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson AF, Joshi VV, Ellison DA, Cedars JC. Zygomycosis in neonates. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1997;16:812–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diven SC, Angel CA, Hawkins HK, Rowen JL, Shattuck KE. Intestinal zygomycosis due to Absidia corymbifera mimicking necrotizing enterocolitis in a preterm neonate. J Perinatol 2004;24:794–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morales-Aguirre JJ, Aguero-Echeverria WM, Ornelas-Car-solio ME, et al. Successful treatment of a primary cutaneous zygomycosis caused by Absidia corymbifera in a premature newborn. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;23:470–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaoutis TE, Roilides E, Chiou CC, et al. Zygomycosis in children: a systematic review and analysis of reported cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007;26:723–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:634–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mooney JE, Wanger A. Mucormycosis ofthe gastrointestinal tract in children: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1993;12:872–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amin SB, Ryan RM, Metlay LA, Watson WJ. Absidia corymbifera infections in neonates. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26: 990–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis LL, Hawkins HK, Edwards MS. Disseminated mucormycosis in an infant with methylmalonicaciduria. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1990;9:851–854 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig NM, Lueder FL, Pensler JM, et al. Disseminated Rhizopus infection in a premature infant. Pediatr Dermatol 1994;11:346–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng PC, Dear PR. Phycomycotic abscesses in a preterm infant. Arch Dis Child 1989;64:862–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell SJ, Gray J, Morgan ME, Hocking MD, Durbin GM. Nosocomial infection with Rhizopus microsporus in preterm infants: association with wooden tongue depressors. Lancet 1996;348:441–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes C, Driver SJ, Alexander KA. Successful treatment of abdominal wall Rhizopus necrotizing cellulitis in a preterm infant. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1995;14:336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reimund E, Ramos A. Disseminated neonatal gastrointestinal mucormycosis: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Pathol 1994;14:385–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linder N, Keller N, Huri C, et al. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis in a premature infant: case report and review of the literature. Am J Perinatol 1998;15:35–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodward A, McTigue C, Hogg G, Watkins A, Tan H. Mucormycosis of the neonatal gut: a “new” disease or a variant of necrotizing enterocolitis? J Pediatr Surg 1992;27: 737–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parfrey NA. Improved diagnosis and prognosis of mucormycosis A clinicopathologic study of 33 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1986;65:113–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah A, Lagvankar S, Shah A. Cutaneous mucormycosis in children. Indian Pediatr 2006;43:167–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar V, Aggarwal A, Taneja R, et al. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis in a premature neonate and its management by tumescent skin grafting. Br J Plast Surg 2005;58:852–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander P, Alladi A, Correa M, D’Cruz AJ. Neonatal colonic mucormycosis—a tropical perspective. J Trop Pediatr 2005;51:54–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nichol PF, Corliss RF, Rajpal S, Helin M, Lund DP. Perforation of the appendix from intestinal mucormycosis in a neonate. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:1133–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siu KL, Lee WH. A rare cause of intestinal perforation in an extreme low birth weight infant—gastrointestinal mucormycosis: a case report. J Perinatol 2004;24:319–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheffler E, Miller GG, Classen DA. Zygomycotic infection of the neonatal upper extremity. J Pediatr Surg 2003;38:E16–E17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchta V, Kalous P, Otcenasek M, Vanova M. Primary cutaneous Absidia corymbifera infection in a premature newborn. Infection 2003;31:57–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh D, Notrica D. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis in infants and neonates: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:1607–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sridhar S, Jana AK, Thomas S, Solomon R. Mucormycosis of the neonatal gastrointestinal tract. Indian Pediatr 2001;38: 294–297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nissen MD, Jana AK, Cole MJ, Grierson JM, Gilbert GL. Neonatal gastrointestinal mucormycosis mimicking necrotizing enterocolitis. Acta Paediatr 1999;88:1290–1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma MC, Gill SS, Kashyap S, et al. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis—an uncommon isolated mucormycosis. Indian J Gastroenterol 1998;17:131–133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kecskes S, Reynolds G, Bennett G. Survival after gastrointestinal mucormycosis in a neonate. J Paediatr Child Health 1997;33:356–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubin SA, Chaljub G, Winer-Muram HT, Flicker S. Pulmonary zygomycosis: a radiographic and clinical spectrum. J Thorac Imaging 1992;7:85–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller RD, Steinkuller PG, Naegele D. Nonfatal maxillo-cerebral mucormycosis with orbital involvement in a dehydrated infant. Ann Ophthalmol 1980;12:1065–1068 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agarwal K, Sharma M, Singh S, Jain M. Antemortem diagnosis of gastrointestinal mucormycosis in neonates: report of two cases and review of literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2006;49:430–432 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dennis JE, Rhodes KH, Cooney DR, Roberts GD. Nosocomial Rhizopus infection (zygomycosis) in children. J Pediatr 1980;96:824–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vadeboncoeur C, Walton JM, Raisen J, et al. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis causing an acute abdomen in the immunocompromised pediatric patient—three cases. J Pediatr Surg 1994;29:1248–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michalak DM, Cooney DR, Rhodes KH, Telander RL, Kleinberg F. Gastrointestinal mucormycoses in infants and children: a cause of gangrenous intestinal cellulitis and perforation. J Pediatr Surg 1980;15:320–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.du Plessis PJ, Wentzel LF, Delport SD, van Damme E. Zygomycotic necrotizing cellulitis in a premature infant. Dermatology 1997;195:179–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isaacson C, Levin SE. Gastro-intestinal mucormycosis in infancy. S Afr Med J 1961;35:581–584 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varricchio F, Reyes MG, Wilks A. Undiagnosed mucormycosis in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1989;8:660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grim PF III, Demello D, Keenan WJ. Disseminated zygomycosis in a newborn. Pediatr Infect Dis 1984;3:61–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hadley GP. Neonatal mucormycosis. P N G Med J 1981;24: 54–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Budhiraja S, Sood N, Singla S, Gupta V. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis in a neonate: survival without antifungal therapy. Indian J Gastroenterol 2007;26:198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kataria R, Gupta DK, Mitra DK. Colonic mucormycosis in the neonate. Pediatr Surg Int 1995;10:271–273 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pena CE. Deep mycotic infections in Colombia. A clinicopathologic study of 162 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1967; 47:505–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levin SE, Isaacson C. Spontaneous perforation of the colon in the newborn infant. Arch Dis Child 1960;35:378–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neame P, Rayner D. Mucormycosis A report on twenty-two cases. Arch Pathol 1960;70:261–268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gatling RR. Gastric mucormycosis in a newborn infant; a case report. AMA Arch Pathol 1959;67:249–255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keye JD Jr, Magee WE. Fungal diseases in a general hospital; a study of88 patients. Am J Clin Pathol 1956;26:1235–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santulli TV, Schullinger JN, Heird WC, et al. Acute necrotizing enterocolitis in infancy: a review of 64 cases. Pediatrics 1975;55:376–387 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Starke JR, Mason EO Jr, Kramer WG, Kaplan SL. Pharmacokinetics of amphotericin B in infants and children. J Infect Dis 1987;155:766–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kwon DS, Mylonakis E. Posaconazole: a new broad-spectrum antifungal agent. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2007; 8:1167–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Noxafil® product information (posaconazole). Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/label/2006/022003lbl.pdf

- 56.de Repentigny L, St-Germain G, Charest H, Kokta V, Vobecky S. Fatal zygomycosis caused by Mucor indicus in a child with an implantable left ventricular assist device. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008;27:365–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kefala-Agoropoulou K, Farmaki E, Tsiouris J, Roilides E, Velegraki A. Cutaneous zygomycosis in an infant with Pearson syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;50:939–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]