Abstract

Background

Constraints on resources and time often render treatments for anxiety such as psychological interventions impracticable. While synthetic anxiolytic drugs are effective, they are often burdened with adverse events. Other options which are effective and safe are of considerable interest and a welcome addition to the therapeutic repertoire.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety as reported in rigorous clinical trials of kava extract compared with placebo for treating anxiety.

Search methods

All publications describing (or which might describe) randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials of kava extract for anxiety were sought through electronic searches on EMBASE (1974 to January 2005), MEDLINE (1951 to January 2005), AMED (1985 to January 2005)), CISCOM (inception until August 2002) and Central/CCTR and CCDANCTR (issue 1, 2005). The search terms that were used were kava, kawa, kavain, Piper methysticum and Rauschpfeffer (German common name for Piper methysticum). Additionally, manufacturers of kava preparations and experts on the subject were contacted and asked to contribute published and unpublished material. Hand‐searches of a sample of relevant medical journals (Erfahrungsheilkunde 1996 ‐ 2005, Forsch Komplementärmed Klass Naturheilkd 1994 ‐ 2005, Phytomed 1994 ‐ 2005, Alt Comp Ther 1995 ‐ 2005), conference proceedings (e.g. FACT ‐ Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies 1996 ‐ 2005) and our own collection of papers were conducted. No restrictions regarding the language of publication were imposed.

Selection criteria

To be included studies were required to be randomised, controlled trials (RCTs), i.e. trials with a randomised generation of allocation sequences, and conducted placebo‐controlled and double‐blind, i.e. trials with blinding of patients and care providers. Trials using oral preparations containing kava extract as the only component (mono‐preparation) were considered. Trials using single constituents of kava extract alone, assessing kava extract as one of several active components in a combination preparation or as a part of a combination therapy were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted systematically according to patient characteristics, interventions and results. Methodological quality of all trials was evaluated using the standard scoring system developed by Jadad and colleagues. The screening of studies, selection, data extraction, validation and the assessment of methodological quality were performed independently by the two reviewers. Disagreements in the evaluation of individual trials were largely due to reading errors and were resolved through discussion.

Main results

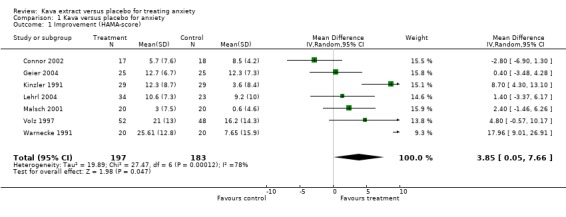

Twelve double‐blind RCTs (n=700) met the inclusion criteria. The meta‐analysis was done on seven studies using the total score on the Hamilton Anxiety (HAM‐A) scale as a common outcome measure. The result suggests a significant effect towards a reduction of the HAM‐A total score in patients receiving kava extract compared with patients receiving placebo (weighted mean difference: 3.9, 95% confidence interval: 0.1 to 7.7; p = 0.05; n = 380). The results of the five studies that were not submitted to meta‐analysis largely support these findings. Adverse events as reported in the reviewed trials were mild, transient and infrequent.

Authors' conclusions

Compared with placebo, kava extract is an effective symptomatic treatment for anxiety although, at present, the size of the effect seems small. The effect lacks robustness and is based on a relatively small sample. The data available from the reviewed studies suggest that kava is relatively safe for short‐term treatment (1 to 24 weeks), although more information is required. Rigorous trials with large sample sizes are needed to clarify the existing uncertainties. Also, long‐term safety studies of kava are required.

Plain language summary

Kava extract for treating anxiety

Systematic literature searches were conducted to assess the evidence for or against the effectiveness of kava extract for treating anxiety. Twenty‐two potentially relevant double‐blind, placebo‐controlled RCTs were identified. Twelve trials met the inclusion criteria. The meta‐analysis of seven trials suggests a significant treatment effect for the total score on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale in favour of kava extract. Few adverse events were reported in the reviewed trials, which were all mild, transient and infrequent. These data imply that, compared with placebo, kava extract might be an effective symptomatic treatment for anxiety although, at present, the size of the effect seems to be small. Rigorous trials with large sample sizes are needed to clarify the existing uncertainties. Particularly long‐term safety studies of kava are needed.

Background

Anxiety disorders commonly occur, seriously impair mental health (Myers 1984), and are of considerable importance in terms of economic burden to society. Data from the United States National Comorbidity Survey suggests a one‐year prevalence of 17% and a lifetime prevalence of almost 25% (Kessler 1994), while annual costs of anxiety disorders have been estimated at approximately $42.3 billion in 1990, which is equivalent to about $1542 per patient (Greenberg 1999). In the majority of cases, patients are treated by general practitioners (Walley 1994, Robinson 1993; Deans 1992) and benzodiazepines are commonly used. However, these are associated with adverse events, which include dependence, sedation and memory impairment (Priest 1988; Gorman 1990; Hunt 1991). Constraints on resources and time often render other treatments such as psychological interventions impracticable. Data from a nationally representative survey conducted in the United States suggest that anxiety patients frequently use complementary and alternative therapies (Kessler 2001; Astin 1998) and one possible option is kava extract (Brevoort 1998).

Kava is the beverage prepared from the rhizome of the kava plant (Piper methysticum Forst.) (Cawte 1985). Throughout the South Pacific extracts of kava have been used for recreational and medicinal purposes. Traditionally, it was used to treat a variety of ailments such as gonorrhoea and to induce relaxation and sleep but also to counteract fatigue (Lebot 1992; Singh 1998). The rhizome of cultivated P. methysticum is used as raw material for the production of kava extract (Habs 1994). In 1998, it was among the top selling herbs in the US totalling approximately $8 million in annual retail sales (Brevoort 1998). In 2000, this had increased to approximately $15 million (Blumenthal 2001). Uncontrolled clinical studies have suggested that kava may be beneficial for treating anxiety (e.g. Melville 1964; Lemert 1967). Data from a previous review confirmed these early findings and suggested a significant reduction of the Hamilton‐Anxiety (HAM‐A) total score of 9.7 points in favor of kava compared with placebo (Pittler 2000a). The exact mechanism of action of kava is unclear. New data from randomised, controlled trials (RCTs) have become available, which prompted us to update this Cochrane review.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety as reported in rigorous clinical trials of kava extract compared with placebo for treating anxiety.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

To be included studies were required to be RCTs, i.e. trials with a randomised generation of allocation sequences, and conducted placebo‐controlled and double‐blind, i.e. trials with blinding of patients and care providers .

Types of participants

Trial participants had to be patients, who were suffering from anxiety.

Types of interventions

Trials using oral preparations containing kava extract as the only component (mono‐preparation) were considered. Trials using single constituents of kava extract alone, assessing kava extract as one of several active components in a combination preparation or as a part of a combination therapy were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Trials assessing clinical outcome measures related to anxiety (e.g.Hamilton Anxiety scale) were included. Of primary interest is the change of baseline to post treatment data. Data on the safety of kava are described as they were reported in the reviewed trials.

Search methods for identification of studies

See: Collaborative Review Group search strategy. All publications describing (or which might describe) randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials of kava extract for anxiety were sought through electronic searches. Databases were searched from their inception: EMBASE (1974 to January 2005), MEDLINE (1951 to January 2005), AMED (1985 to January 2005)), CISCOM (Research Council for Complementary Medicine, London; until August 2002) and Central/CCTR and CCDANCTR (Cochrane Collaborative Depression, Anxiety & Neurosis Controlled Trials register) on the Cochrane Library (issue 1, 2005).

The search terms that were used were kava, kawa, kavain, Piper methysticum and Rauschpfeffer (German common name for Piper methysticum). Manufacturers of kava preparations and experts on the subject were contacted and asked to contribute published and unpublished material.

Hand‐searches of a sample of relevant medical journals (Erfahrungsheilkunde 1996 ‐ 2005, Forsch Komplementärmed Klass Naturheilkd 1994 ‐ 2005, Phytomed 1994 ‐ 2005, Alt Comp Ther 1995 ‐ 2005), conference proceedings (e.g. FACT ‐ Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies 1996 ‐ 2005) and our own collection of papers were conducted.

The bibliographies of all papers located were searched for further trials. No restrictions regarding the language of publication were imposed.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection

The screening of studies, selection, data extraction, validation and the assessment of methodological quality were performed independently by the two reviewers.

Data extraction

Articles in languages other than English or German were translated in‐house. Data were extracted systematically according to the methods used, outcome measures, patient characteristics, interventions, results and adverse events.

Assessment of methodological quality

Methodological quality was evaluated using the scoring system developed by Jadad and colleagues (Jadad 1996), which quantifies the likelihood of bias inherent in the trials, based on the description of randomisation, blinding and withdrawals. Disagreements in the evaluation of trials were largely due to reading errors and were resolved through discussion.

Data analysis

Meta‐analysis was performed using standard meta‐analysis software (RevMan 4.2.7, Update Software Ltd., Oxford, England). It uses the inverse of the variance to assign a weight to the mean of the within‐study treatment effect. For most studies, however, the information was insufficient to allow us to directly calculate the variance of the pre‐intervention to post‐intervention change. The Cochrane Collaboration suggests to impute the variance of the change by assuming a correlation factor of 0.4 between pre‐intervention and post‐intervention values. The variance of the change was imputed using this correlation factor and then used to assign a weight to the mean of the within‐study treatment effect. In addition, further information was sought through contacting the authors of the original trials and the manufacturer of the preparations that were used. The meta‐analysis was performed using the weighted mean difference.

The treatment effect was calculated using a random effects model. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity tested whether the distribution of the results was compatible with the assumption that inter‐trial differences were attributable to chance variation alone.

Sensitivity analyses were performed post‐hoc to test the robustness of the main analysis. For the meta‐analyses the data were re‐calculated based on the original raw data except for Conn 2001.

Results

Description of studies

For this update, one new study was identified (Connor 2002). Previously unpublished trials are now published (Gastpar 2003; Geier 2004; Lehrl 2004). In total, twenty‐two potentially relevant double‐blind, placebo‐controlled RCTs were identified (Lehmann 1998; Lehmann 1996; Lehmann 1989; Lindenberg 1990; Bhate 1992; Bhate 1989; Möller 1992; Möller 1989; Staedt 1991; Malsch 2001; Kinzler 1991; Warnecke 1991; Warnecke 1990; Warnecke 1986; Warnecke 1989; Volz 1997; Singh 1998; De Leo 2001; Geier 2004; Lehrl 2004; Gastpar 2003; Connor 2002). Two studies were duplicate publications (Lehmann 1996; Bhate 1992), eight others were excluded because they were either not performed with a kava extract monopreparation (Warnecke 1989; Warnecke 1986), were performed as part of a combination therapy (De Leo 2001) or were performed using kavain (Möller 1992; Möller 1989; Lehmann 1989; Staedt 1991; Lindenberg 1990). Twelve double‐blind, placebo‐controlled RCTs met all inclusion criteria and were reviewed. Seven trials assessed a common outcome measure and provided data, which were suitable for meta‐analysis (Geier 2004; Lehrl 2004; Connor 2002; Malsch 2001; Volz 1997; Kinzler 1991; Warnecke 1991). All, except one (Connor 2002), used the same preparation (WS1490), which is standardised to 70 % kavalactone content and is produced by the same manufacturer. Key data from all included trials are presented in the characteristics of included trials table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Six trials scored the maximum of 5 points on the Jadad scale (Jadad 1996). Four of seven trials that could be included in the meta‐analysis scored the maximum of 5 points, while three other trials lacked either a description of randomization procedures (Lehrl 2004; Malsch 2001) or lacked a description of randomization and double‐blinding procedures (Volz 1997).

Effects of interventions

A total of twelve double‐blind RCTs (n=700) were reviewed (Characteristics of included studies table). Six trials reported adverse events experienced by patients receiving kava extract. Stomach complaints, restlessness, drowsiness, tremor, headache and tiredness were reported most frequently. Four trials comprising 30% of patients in the reviewed trials report the absence of adverse events while taking kava extract. None of the trials reported any hepatotoxic events. Seven of the reviewed trials (Gastpar 2003; Geier 2004; Lehrl 2004; Conn 2001 reported in Connor 2001; Malsch 2001; Volz 1997; Warnecke 1991) measured liver enzyme levels as safety parameters and report no clinically signifcant changes. Data from seven trials (n=380) assessed a common outcome measure ‐ the total score on the HAM‐A scale ‐ and were included in the meta‐analysis (Lehrl 2004; Geier 2004; Connor 2002; Malsch 2001; Volz 1997; Kinzler 1991; Warnecke 1991). 74 % of these patients (n = 282) were diagnosed according to the criteria of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐IV). All trials used the HAM‐A total score at baseline as an inclusion criterion and four trials included patients if the total score was 19 or above (Characteristics of included studies table). The result of the meta‐analysis suggests an effect towards a reduction of the HAM‐A total score in patients receiving kava extract compared with patients receiving placebo (weighted mean difference: 3.9, 95% confidence interval: 0.1 to 7.7; p = 0.05; n = 380). The chi‐square test indicated heterogeneity (chi square = 27.5; p = 0.0001 ). Visual inspection of the forest plot identified two outlier (Connor 2002; Warnecke 1991), which were mainly responsible for the heterogeneity. Warnecke 1991 was the only one that included only women with anxiety due to climacteric syndrome. Connor 2002 was the only trial that did not use the kava preparation WS1490. Other potential sources of clinical heterogeneity (dose of kava, duration of treatment, degree of baseline severity or setting) could not be identified (Characteristics of included studies table). Removing these trials and pooling the data of the remaining five trials (chi square = 9.0; p = 0.06) suggests a significant reduction of the HAM‐A total score in patients receiving kava extract compared with patients receiving placebo (weighted mean difference: 3.4, 95% confidence interval: 0.5 to 6.4; p = 0.02; n = 305).

Other sensitivity analyses testing the robustness of the main analysis assessed whether including only the data of patients with non‐psychotic anxiety diagnosed according to the criteria of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐IV) criteria (Geier 2004; Lehrl 2004; Connor 2002; Malsch 2001; Volz 1997) would alter the direction of the result. The meta‐analysis of these data (chi square = 5.8; p = 0.2) suggests a non‐significant effect (weighted mean difference: 1.0, 95% confidence interval: ‐1.3 to 3.3; p = 0.4; n = 282). The analysis of trials assessing outpatients with non‐psychotic anxiety patients and a HAM‐A total score of 19 or above (Geier 2004; Kinzler 1991; Volz 1997) who received 200 to 210 mg kavalactones daily (chi square = 7.7; p = 0.02) indicated a non‐significant trend (weighted mean difference: 4.5, 95% confidence interval: ‐0.6 to 9.7; p = 0.08; n = 208).

The results of the five studies that were not submitted to meta‐analysis largely support these findings (see characteristics of included studies). Singh 1998 reported a reduction in favour of kava compared with placebo for the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory. Two studies reported a reduction on the Zung Anxiety Status Inventory (Gastpar 2003; Warnecke 1990), whereas Bhate 1989 reported a reduction compared with placebo on a 10‐Item Anxiety Scale. Lehmann 1998 assessed the responder‐non‐responder ratio and found a differential effect in favour of kava.

Discussion

The addition of one new trial (Connor 2002 ) has reduced the effect by one point on the HAM‐A total score, which is of borderline statistical significance. Thus, compared with placebo, kava extract might be an effective symptomatic treatment for anxiety although, at present, the size seems to be small. The effect lacks robustness as indicated by the sensitivity analyses and is based on a relatively small sample. Nonetheless, the reviewed trials which could not be included in the meta‐analysis support the findings and suggest that kava is beneficial for patients with anxiety when compared with placebo. This is corroborated by the results of comparative trials (Boerner 2003) other systematic reviews (Jorm 2004) and previous reviews (Singh 1998; Weber 1994; Chrubasik 1997; Hänsel 1996). However, larger rigorous trials, particularly in long‐term studies, are needed.

In our own systematic review assessing the safety of kava (Stevinson 2002), two drug monitoring studies of kava were located. They included a total of 7078 patients taking kava extract equivalent to 105 mg to 240 mg kavalactones per day for 5 to 7 weeks. In these studies no cases of hepatotoxicity emerged, which is supported by a further study (Connor 2001). Two other postmarketing surveillance studies, including 1673 patients who received kava extract equivalent to 120 mg kavalactones daily for 5 weeks (Spree 1992) and 2944 other patients who received 400 mg kavain daily for 4 weeks (Unger 1988) corroborate this and report no hepatotoxic events. Indeed, kava hepatotoxicity seems to be a very rare event (Teschke 2003; Schulze 2003). No plausible mechanism for the alleged hepatotoxic effects of kava has so far been identified. The question therefore remains whether the frequency of liver damage in kava users differs significantly from that of non‐kava users.

Limitations of this meta‐analysis pertain to the citation tracking and its potential incompleteness. Although strong efforts were made to locate and retrieve all trials on the subject, it is conceivable that some were not uncovered. The distorting effects on systematic reviews arising from publication bias and location bias are well‐documented (Easterbrook 1991; Egger 1998). There are also suggestions that positive findings may be overrepresented in complementary medicine journals (Ernst 1997; Schmidt 2001, Pittler 2000b). In addition, there is evidence for the tendency of positive findings to be published in English language journals (Egger 1997) and for some European journals to not be indexed in major medical databases (Nieminen 1999). Therefore the possibility of treatment effects to be exaggerated exists, which may be particularly relevant to herbal medicinal products where much of the evidence originates from European countries. Databases searched for the purposes of this study included those with a focus on the American and European literature and those that specialize in complementary medicine. There were no restrictions in terms of publication language. We are therefore confident that this strategy has minimized bias in the present study.

Other pharmacological options include antidepressants and benzodiazepines. The latter, however, may cause adverse events such as sedation, amnesia, developement of tolerance and carry an increased risk of road‐traffic accidents (Barbone 1998; Moore 1998; O'Neill 1998). Comparative studies that were identified during the searches suggest the absence of significant differences between benzodiazepines and kavain or kava extract (Lindenberg 1990; Woelk 1993) in terms of effectiveness. However, a systematic assessment is required for firm statements. Also, more equivalence studies are needed, not least to define the relative risks of both approaches.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Compared with placebo, kava extract is an effective symptomatic treatment for anxiety although, at present, the size of the effect seems to be small. The effect lacks robustness and is based on a relatively small sample. The data available from the reviewed studies suggest that kava is relatively safe for short‐term treatment (1 to 24 weeks), although more information is required.

Implications for research.

Rigorous trials with large sample sizes are needed to clarify the existing uncertainties. Also, long‐term safety studies of kava are required.

Feedback

Comment Safety warns about kava

Summary

We've been alerted to safety concerns about kava products, noting that Swiss and German authorities have withdrawn these from the market after concerns about liver toxicity. The US FDA is also investigating the status of kava. We have added a notice to the Cochrane Consumer Network website, but would like to see this information included in the review as a matter of urgency. We believe that consumers would like to know that some countries believe these products may not be safe.

I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter of my criticisms.

Reply

Please see response to Comment Number 02.

Contributors

Comment Safety warns about kava Sender Hilda Bastian Sender Email hilda.bastian@cochraneconsumer.com Date Received 19/03/02 04:27:00

Comment Update on safety warnings for kava

Summary

New information has surfaced since the message posted on 19/3/02. In addition, one correction is in order for this earlier message.

The US Food and Drug Administration issued a Consumer Advisory on 25/03/2002 (http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/%7Edms/addskava.html) in which it "advises consumers of the potential risk of severe liver injury associated with the use of kava‐containing dietary supplements." The agency recommends that "persons who have liver disease or liver problems, or persons who are taking drug products that can affect the liver, should consult a physician before using kava‐containing supplements." The agency also urges both consumers and physicians to report cases of liver or other injuries that may be associated with kava.

The American Herbal Products Association adopted the following labeling recommendation for kava products on 26/03/02: "Caution: Ask a healthcare professional before use if you have or have had liver problems, frequently use alcoholic beverages, or are taking any medication. Stop use and see a doctor if you develop symptoms that may signal liver problems (e.g., unexplained fatigue, abdominal pain, fever, vomiting, dark urine, yellow eyes or skin). Not for use by persons under 18 years of age, or by pregnant or breastfeeding women. Not for use with alcoholic beverages. Excessive use, or use with products that cause drowsiness, may impair your ability to operate a vehicle or heavy equipment."

Hilda Bastien's 19/03/02 message should be corrected to note that German health authorities have not, in fact, withdrawn kava products. Rather, they proposed withdrawal in November, 2001 and requested information to evaluate their proposal. It is my understanding that no final decision has yet been made. Similarly, while some kava products have been removed from the Swiss market, others continue to be sold there.

US FDA was cautious in its communication to refer to any association between kava and the liver as "potential." Nevertheless, the recommendation made by Bastien that consumers be informed of the current concerns that have been expressed by health authorities is sound and is supported by the U.S. herbal trade.

As the President of a trade association that represents manufacturers and marketers of herbal products, including kava products, I have a periferal affiliation with companies that do have a financial interst in this matter. I certify that I have no commercial affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter of my criticisms.

Reply

At the time of writing (August 2002) 68 documented cases of suspected kava hepatotoxicity were on record worldwide. In many of these instances, the exact nature of the extract was not specified. It is clear, however, that all types of extract and synthetic kavain are implicated. In the vast majority of these cases other drugs ‐ some with known hepatotoxicity ‐ were taken concomitantly, a fact, which considerably complicates causal attribution. Similarly, in many of these case reports no data for alcohol consumption or viral infection are provided. The problems typically occurred 2 to 3 months after kava intake; in some cases the length of kava use was not known. The adverse events ranged from mere transient elevations of liver enzymes to severe (often cholestatic) hepatitis and fulminant liver failure. In most instances the patients seemed to have recovered fully after discontinuation of kava. However, 6 patients required liver transplants and 3 patients died. Reliable incidence or prevalence figures are not currently available.

Contributors

Comment Update on safety warnings for kava Sender Michael McGuffin Sender Description President, American Herbal Products Association Sender Email mmcguffin@ahpa.org Sender Address 8484 Georgia Ave., #370 Silver Spring, MD 20910 USA Date Received 14/06/02 16:33:23

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 April 2010 | Amended | Contact authors' details amended |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2001 Review first published: Issue 4, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 March 2010 | Amended | Contact details of contact/first author updated; search dates synchronised |

| 2 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 20 November 2002 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback was added, together with a response, on 20 November 2002. |

| 18 November 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

None

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Kava versus placebo for anxiety.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Improvement (HAMA‐score) | 7 | 380 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.85 [0.05, 7.66] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Kava versus placebo for anxiety, Outcome 1 Improvement (HAMA‐score).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bhate 1989.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Pre‐operative patients (n=59); General hospital, Germany | |

| Interventions | 300 mg (60 mg kavalactones) night before operation and 300 mg (60 mg) 1 hour before operation | |

| Outcomes | 10‐Item Anxiety Scale. Differential reduction of anxiety in favour of kava (p<0.05) | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): postoperative hangover Jadad score: 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Connor 2002.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder (DSM‐IV) ; HAMA total score 16 or above (per‐protocol; n=35); University outpatient setting, US | |

| Interventions | 140 mg kavalactones daily for 1 week, then 280 mg kavalactones daily for 3 weeks | |

| Outcomes | HAM‐A total score. Mean difference, 95% confidence interval ‐2.8; ‐5.4 to ‐0.2 | |

| Notes | 'No evidence of withdrawal or sexual side effects' Jadad score: 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Gastpar 2003.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind, multicenter; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Outpatients with neurotic anxiety (DSM‐III‐R) ; HAMA total score 19 or above (intention‐to‐treat; n=141); 17 general practices in Germany | |

| Interventions | 50 mg 3 times (105 mg kavalactones) daily for 4 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Zung Anxiety Status Inventory. Reduction compared with baseline in kava group (p<0.001) | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): tiredness, symptom aggravation, unrelated to the investigational treatment (not detailed), Jadad score: 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Geier 2004.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Patients with nonpsychotic anxiety (DSM‐III‐R) ; HAMA total score 19 or above (intention‐to‐treat; n=50); Hospital setting, Germany | |

| Interventions | 50 mg 3 times (105 mg kavalactones) daily for 4 weeks | |

| Outcomes | HAM‐A total score. Mean difference, 95% confidence interval 0.4; ‐3.5 to 4.3 | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): Pleuro pneumonia; deterioration of pre‐existing pulmonary fibrosis Jadad score: 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Kinzler 1991.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Outpatients with nonpsychotic anxiety syndrome (ICD 9); HAMA 19 or above (intention‐to‐treat; n=58); University outpatient setting, Germany | |

| Interventions | 100 mg 3 times (210 mg kavalactones) daily for 4 weeks | |

| Outcomes | HAM‐A total score. Mean difference, 95% confidence interval 8.7; 4.3 to 13.1 | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): none Jadad score: 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Lehmann 1998.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind;2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Pre‐operative women (n=20); University hospital, Germany | |

| Interventions | 150 mg 3 times (150 mg kavalactones) daily for 1 week | |

| Outcomes | Responder ‐ non‐responder ratio. Differential reduction of anxiety in favour of kava (p<0.05) | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): not detailed Jadad score: 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lehrl 2004.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind, multicenter; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Patients with sleep disturbances associated with nonpsychotic anxiety (DSM‐III‐R) ; HAMA total score 16 or above (intention‐to‐treat; n=57); 3 centers in Germany | |

| Interventions | 200 mg once (140 mg kavalactones) daily for 4 weeks | |

| Outcomes | HAM‐A total score. Mean difference, 95% confidence interval 1.4; ‐3.4 to 6.2 | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): none Jadad score: 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Malsch 2001.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Outpatients with nonpsychotic anxiety and pretreatment with benzodiazepines (DSM‐III‐R); HAMA total score of 14 or below (median at baseline: 13 kava / 13 placebo; intention‐to‐treat; n=40); General Hospital, Hamburg, Germany | |

| Interventions | Tapering off benzodiazepines and increase from 50 to 300 mg (210 mg kavalactones) daily for 1 week. Then 100 mg 3 times daily for 3 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | HAM‐A total score. Mean difference, 95% confidence interval 2.4; ‐1.5 to 6.3 | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): not detailed Jadad score: 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Singh 1998.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Patients with anxiety diagnosed using the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (n=60); University setting, US | |

| Interventions | 400 mg 2 times (240 mg kavalactones) daily for 4 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | State‐trait Anxiety Inventory. Differential reduction in favour of kava (p<0.0001); no differential effect for trait anxiety | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): none Jadad score: 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Volz 1997.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind, multicenter; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Outpatients with nonpsychotic anxiety (DSM‐III‐R); HAMA total score 19 or above (intention‐to‐treat; n=100); General practice, Germany | |

| Interventions | 100 mg 3 times (210 mg kavalactones) daily for 24 weeks | |

| Outcomes | HAM‐A total score. Mean difference, 95% confidence interval 4.8; ‐0.6 to 10.2 | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): not detailed; stomach upset were rated by the investigators as possibly related to the intake of kava Jadad score: 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Warnecke 1990.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Female outpatients with anxiety due to climacteric syndrome (n=40); Gynaecology practice, Germany | |

| Interventions | 150 mg 2 times (60 mg kavalactones) daily for 4 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Zung Anxiety Status Inventory. Reduction compared with baseline in kava group (p<0.001); no effect in placebo group | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): headache, tiredness and lack of energy; stomach complaints, heartburn and diarrhoea Jadad score: 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Warnecke 1991.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled double‐blind; 2 parallel groups | |

| Participants | Female outpatients with anxiety due to climacteric syndrome; HAMA total score 19 or above (intention‐to‐treat; n=40); Gynaecology practice, Germany | |

| Interventions | 100 mg 3 times (210 mg kavalactones) daily for 8 weeks | |

| Outcomes | HAM‐A total score. Mean difference, 95% confidence interval 17.9; 9.0 to 26.9 | |

| Notes | Adverse events (kava group): restlessness, stomach complaints, drowsiness, tremor Jadad score: 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bhate 1992 | duplicate publication |

| De Leo 2001 | conducted in combination with hormone replacement therapy |

| Lehmann 1989 | assessed a single constituent of kava extract |

| Lehmann 1996 | duplicate publication (translated from Kienzler E et al . 1991) |

| Lindenberg 1990 | assessed a single constituent of kava extract |

| Möller 1989 | assessed a single constituent of kava extract |

| Möller 1992 | assessed a single constituent of kava extract |

| Staedt 1991 | assessed a single constituent of kava extract |

| Warnecke 1986 | assessed a combination preparation containing kava extract |

| Warnecke 1989 | assessed a combination preparation containing kava extract |

Contributions of authors

Conception and design: MH Pittler, E Ernst Literature searches: MH Pittler Analysis and interpretation of the data: MH Pittler, E Ernst Drafting of the article: MH Pittler, E Ernst Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: MH Pittler, E Ernst Final approval of the article: MH Pittler, E Ernst

Sources of support

Internal sources

Peninsula Medical School, Universities of Exeter and Plymouth, UK.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bhate 1989 {published data only}

- Bhate H, Gerster G, Gracza E. Orale Prämedikation mit Zubereitungen aus Piper methysticum bei operativen Eingriffen in Epiduralanästhesie. Erfahrungsheilkunde 1989;38(6):339‐35. [Google Scholar]

Connor 2002 {published data only}

- Connor KM, Davidson JR. A placebo‐controlled study of kava kava in generalized anxiety disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 2002;17(4):185‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gastpar 2003 {published data only}

- Gastpar M, Klimm HD. Treatment of anxiety, tension and restlessness states with kava special extract WS1490 in general practice: A randomized placebo‐controlled double‐blind multicenter trial. Phytomedicine 2003;20(10):631‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Geier 2004 {published data only}

- Geier FP, Konstantinowicz T. Kava treatment in patients with anxiety. Phytotherapy Research 2004;18(4):297‐300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kinzler 1991 {published data only}

- Kinzler E, Krömer J, Lehmann E. Effect of a special kava extract in patients with anxiety‐, tension‐, and excitation states of non‐psychotic genesis Double blind study with placebos over 4 weeks [Wirksamkeit eines Kava‐Spezial‐Extraktes bei Patieinten mit Angst‐, Spannungs‐ und Erregungszuständen nicht‐psychotischer Genese]. Arzneimittelforschung 1991;41(6):584‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lehmann 1998 {published data only}

- Lehmann E. Wirkung bei Kava ‐ Kava bei akuter Angst. Synopsis 1998;2:57‐64. [Google Scholar]

Lehrl 2004 {published data only}

- Lehrl S. Clinical efficacy of kava extract WS1490 in sleep disturbances associated with anxiety disorders. Results of a multicenter randomized placebo‐controlled double‐blind clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders 2004;78(2):101‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Malsch 2001 {published data only}

- Malsch U, Kieser M. Efficacy of kava‐kava in the treamtent of non‐psychotic anxiety, following pretreatment with benzodiazepines. Psychopharmacology 2001;157(3):277‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Singh 1998 {published data only}

- Singh NN, Ellis CR, Sharp I, Eakin K, Best AM, Singh YN. A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study of the effects of kava (Kavatrol) on daily stress and anxiety in adults. Alternative Therapies (Natrol in‐house publication 1997) 1998;4:97‐8. [Google Scholar]

Volz 1997 {published data only}

- Volz HP, Kieser M. Kava‐kava extract WS1490 versus placebo in anxiety disorders ‐ a randomized placebo‐controlled 25‐week outpatient trial. PharmacopsychiatRY 1997;30(1):1‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Warnecke 1990 {published data only}

- Warnecke G, Pfaender H, Gerster G, Gracza E. Efficacy of an extract of Kavaroot in patients with climacteric syndrome [Wirksamkeit von Kawa‐Kawa‐Extrakt beim klimakterischen Syndrom]. Zeitschrift fur Phytotherapie 1990;11(3):81‐6. [Google Scholar]

Warnecke 1991 {published data only}

- Warnecke G. Psychosomatic dysfunctions in the female climacteric Clinical effectiveness and tolerance of Kava Extract WS‐1490 [Psychosomatische Dysfunktionen im weiblichen Klimakterium Klinische Wirksamkeit und Vertraglichkeit von KavaExtrakt WS 1490]. Fortschritte der Medizin 1991;109(4):119‐22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Bhate 1992 {published data only}

- Bhate H, Gerster G. Behandlung mit Phytotranquilizern vor der Narkose. Therapeutikon 1992;6:214‐22. [Google Scholar]

De Leo 2001 {published data only}

- Leo V, Marca A, Morgante G, Lanzetta D, Floria P, Petraglia F. Evaluation of combining kava extract with hormone replacement therapy in the treatment of postmenopausal anxiety. Maturitas 2001;39(2):185‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lehmann 1989 {published data only}

- Lehmann E, Klieser E, Klimke A, Krach H, Spatz R. The efficacy of cavain in patients suffering from anxiety. Pharmacopsychiatry 1989;22.(6):258‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lehmann 1996 {published data only}

- Lehmann E, Kinzler E, Friedmann J. Efficacy of a special kava extract (Piper methysticum) in patients with states of anxiety, tension and exitedness of non‐mental origin ‐ a double‐blind placebo‐controlled study of four weeks treatment. Phytomedicine 1996;3(2):113‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lindenberg 1990 {published data only}

- Lindenberg D, Pitule‐Schödel H. D,L‐kavain in comparison with oxazepam in anxiety disorders A double‐blind study of clinical effectiveness [D,L‐Kavain im Vergleich zu Oxazepam bei Angstzuständen. Doppelblindstudie aur Wirksamkeit]. Fortschritte der Medizin 1990;108(2):49‐50, 53‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Möller 1989 {published data only}

- Möller HJ, Heuberger L. Anxiolytic potency of D,L‐kavain. Results of a placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study [Anxiolytische Potenz von D,L‐Kavain]. Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift 1989;131(37):656‐9. [Google Scholar]

Möller 1992 {published data only}

- Möller HJ, Ulm K, Glöggler A. Kavain as an aid in the withdrawal of benzodiazepines (Therapy study) [Kavain als Hilfe beim Benzodiazepin‐Entzug]. Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift 1992;134(37):41‐4. [Google Scholar]

Staedt 1991 {published data only}

- Staedt U, Holm E, Heep J, Riesmüller S, Kortsik C, Steiner G. Studies on effects of D,L‐Kawain‐psychometry, EEG and Hamilton scale [Zum Wirkungsprofil von D,L‐Kavain]. Medizinische Welt 1991;42(10):881‐91. [Google Scholar]

Warnecke 1986 {published data only}

- Warnecke G, Gerster G, Jäger H. Anxiolytic effect with a phytotranquilizer in gynecology [Anxiolyse mit einem Phyto‐Tranquilizer in der Frauenheilkunde]. Medizinische Welt 1986;37(44):1379‐83. [Google Scholar]

Warnecke 1989 {published data only}

- Warnecke G. Langzeittherapie psychischer und vegetativer Dysrepulationen mit Zubereitungen aus Piper methysticum. Erfahrungsheilkunde 1989;38(6):333‐8. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Astin 1998

- Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine. Results of a national study. JAMA 1998;279:1548‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barbone 1998

- Barbone F, McMahon AD, Davey PG, Morris AD, Reid IC, McDevitt DG, et al. Association of road‐traffic accidents with benzodiazepine use. Lancet 1998;352:1331‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blumenthal 2001

- Blumenthal M. Herb sales down 15 percent in mainstream market. Herbalgram 2001;51:69. [Google Scholar]

Boerner 2003

- Boerner RJ, Sommer H, Berger W, Kuhn U, Schmidt U, Mannel M. Kava kava extract LI150 is as effective as opipramol and buspirone in generalized anxiety disorder ‐ An 8‐week randomized double‐blind multi‐centre clinical trial in 129 out‐patients. Phytomedicine 2003;10:38‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brevoort 1998

- Brevoort P. The booming US botanical market ‐ a new overview. Herbalgram 1998;44:33‐46. [Google Scholar]

Cawte 1985

- Cawte J. Psychoactive substances of the south seas: betel, kava and pituri. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 1985;19:83‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chrubasik 1997

- Chrubasik S. Klinisch geprüfte Wirksamkeit bei nervösen Angst‐, Spannungs‐ und Unruhezuständen. Der Allgemeinarzt 1997;18:1683‐7. [Google Scholar]

Connor 2001

- Connor KM, Davidson JR, Churchill LE. Adverse‐effect profile of kava. CNS Spectrum 2001;6:848‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deans 1992

- Deans HG, Skinner P. Doctors' views on anxiety management in general practice. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 1992;85:83‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Easterbrook 1991

- Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991;337:867‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Zellweger‐Zähner T, Schneider M, Junker C, Lengeler C, Antes G. Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. Lancet 1997;350:326‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1998

- Egger M, Smith GD. Bias in location and selection of studies. BMJ 1998;316:61‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ernst 1997

- Ernst E, Pittler MH. Alternative therapy bias. Nature 1997;385:480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gorman 1990

- Gorman JM, Papp LA. Chronic anxiety: deciding the length of treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1990;51 Suppl 1:11‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Greenberg 1999

- Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Davidson JR, et al. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1999;60:427‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Habs 1994

- Habs M, Honold E. Der psychoaktive Spezialextrakt WS 1490 aus dem Wurzelstock von Piper methysticum (Kava‐Kava) ‐ ein Report. Forschende Komplementarmedizin 1994;1:208‐15. [Google Scholar]

Hofmann 1996

- Hofmann R, Winter U. Therapeutische Möglichkeiten mit Kava‐Kava bei Angsterkrankungen. Psycho 1996;22 Suppl:51‐3. [Google Scholar]

Hunt 1991

- Hunt C, Singh M. Generalized anxiety disorder. International Review of Psychiatry 1991;3:215‐29. [Google Scholar]

Hänsel 1996

- Hänsel R, Kammerer S. Kava‐Kava. Basel: Aesopus, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Jadad 1996

- Jadad AR, Moore A, Carroll D Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomised clinical trials: Is blinding necessary?. Controlled Clinical Trials 1996;17:1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jorm 2004

- Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Parslow RA, RodgersRA, Blewitt KA. Effectiveness of complementary and self‐help treatments for anxiety disorders. MJA 2004;181:S29‐S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kessler 1994

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12‐month prevalence of DSM‐III‐R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 1994;51:8‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kessler 2001

- Kessler RC, Soukup J, Davis RB, Foster DF, Wilkey SA, Rompay MI, et al. The use of complementary and alternative therapies to treat anxiety and depression in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry 2001;158:289‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lebot 1992

- Lebot V, Merlin M, Lindstrom L. Kava, the pacific drug. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

Lemert 1967

- Lemert EM. Secular use of kava in Tonga. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 1967;28:328‐41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Melville 1964

- Melville H. Typee: a peep at Polynesian life during a four months' residence in a valley of the Marquesas. New York, NY: Signet, 1964. [Google Scholar]

Moore 1998

- Moore A, McQuay H, Muir Gray JA. Benzodiazepines and car crashes. Bandolier 1998;57:6. [Google Scholar]

Myers 1984

- Myers JK, Weissman MM, Tischler GL, Holzer CE, Leaf PJ, Orvaschel H, et al. Six‐month prevalence of psychiatric disorders in three communities 1980 to 1982. Archives of General Psychiatry 1984;41:959‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nieminen 1999

- Nieminen P, Isohanni M. Bias against European journals in medical publication databases. Lancet 1999;353:1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Neill 1998

- O'Neill D. Benzodiazepines and driver safety. Lancet 1998;352:1324‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pittler 2000a

- Pittler MH, Ernst E. Efficacy of kava extract for treating anxiety: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2000;20:84‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pittler 2000b

- Pittler MH, Abbot NC, Harkness EF, Ernst E. Location bias in controlled clinical trials of complementary/alternative therapies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2000;53:485‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Priest 1988

- Priest RG, Montgomery SA. Benodiazepines and dependence: a college statement. Bulletin of the Royal College of Psychiatrists 1988;12:107‐8. [Google Scholar]

Robinson 1993

- Robinson MD. Anxiety disorders in the general practice. New Jersey medicine : the journal of the Medical Society of New Jersey 1993;90:129‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schmidt 2001

- Schmidt K, Pittler MH, Ernst E. Bias in alternative medicine is still rife but is diminishing. BMJ 2001;323:1071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schulze 2003

- Schulze J, Raasch W, Siegers CP. Toxicity of kava pyrones, drug safety and precautions ‐ a case study. Phytomedicine 2003;10:68‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Siegers 1990

- Siegers CP, Honold E, Krall B, Meng G, Habs M. Ergebnisse einer Anwendungsbeobachtung L1090 mit Laitan® Kapseln. Ärztliche Forschung 1992;39:7‐11. [Google Scholar]

Singh 1998

- Singh YN, Blumenthal M. Kava, an overview. Herbalgram 1998;39:33‐55. [Google Scholar]

Spree 1992

- Spree MH, Croy HH. Antares ‐ ein standardisiertes Kava‐Kava Präparat mit dem Spezialextrakt KW 1491. Der Kassenarzt 1992;17:44‐7. [Google Scholar]

Stevinson 2002

- Stevinson C, Huntley A, Ernst. A systematic review of the safety of kava extract in the treatment of anxiety. Drug Safety 2002;25:251‐61.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Teschke 2003

- Teschke R, Gaus W, Loew D. Kava extracts: Safety and risks including rare hepatoxicity. Phytomedicine 2003;10:440‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Unger 1988

- Unger L. Veränderung psychovegetativer Beschwerden unter Therapie mit Kavain. Therapiewoche 1988;38:3171‐4. [Google Scholar]

Walley 1994

- Walley EJ, Beebe DK, Clark JL. Management of common anxiety disorders. American Family Physician 1994;50:1745‐53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weber 1994

- Weber U, Winter U. Kava‐Kava ‐ ein pflanzliches Anxiolytikum. Fundamenta Psychiatrica 1994;8:204‐10. [Google Scholar]

Woelk 1993

- Woelk H, Kapoula O, Lehrl S, Schröter K, Weinholz P. Behandlung von Angst‐Patienten. Zeitschrift fuer Allgemeinmedizin 1993;69:271‐7. [Google Scholar]