Abstract

Background

Non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) is effective in treating acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Nocturnal non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation (nocturnal‐NIPPV) has been proposed as an intervention for stable hypercapnic patients with COPD.

Objectives

To assess the effects of nocturnal‐NIPPV at home via nasal mask or face mask in people with COPD by using a meta‐analysis based on individual patient data (IPD).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register. We performed the latest search in August 2012.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials in people with stable COPD that compared nocturnal‐NIPPV at home for at least five hours per night, for at least three consecutive weeks plus standard therapy with standard therapy alone.

Data collection and analysis

IPD were collected and two review authors assessed risk of bias independently.

Main results

This update of the systematic review on nocturnal‐NIPPV in COPD (Wijkstra 2002), has led to the inclusion of three new studies, leading to seven included studies on 245 people. We obtained IPD for all participants in all included studies. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of all outcomes included zero. These included partial pressure of CO2 and O2 in arterial blood, six‐minute walking distance (6MWD), health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), maximal inspiratory pressure (PImax) and sleep efficiency. The mean effect on 6MWD was small at 27.7 m and not statistically significant. Given the width of the 95% CI (‐28.1 to 66.3 m), the real effect of NIPPV on 6MWD is uncertain and we cannot exclude an effect that is clinically significant (considering that the minimal clinically difference on 6MWD is around 26 m).

Authors' conclusions

Nocturnal‐NIPPV at home for at least three months in hypercapnic patients with stable COPD had no consistent clinically or statistically significant effect on gas exchange, exercise tolerance, HRQoL, lung function, respiratory muscle strength or sleep efficiency. Meta‐analysis of the two new long‐term studies did not show significant improvements in blood gases, HRQoL or lung function after 12 months of NIPPV. However, the small sample sizes of these studies preclude a definite conclusion regarding the effects of NIPPV in COPD.

Plain language summary

Non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation (ventilators) used at night by people with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Background: Non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) is a method to assist or replace spontaneous breathing (or normal breathing) with the aid of a machine called a ventilator. A mask is fitted over the nose or mouth, or both and air is pushed into the lungs. It can be used as a short‐term measure, during critical instances in the hospital, but also at home for longer periods in people who have raised levels of carbon dioxide in their blood. We wanted to discover whether using NIPPV at home during the night alongside standard therapy was better or worse than standard therapy alone in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). COPD is a progressive disease that makes it hard to breathe. In 2002, we published our original Cochrane review looking at this. It is important to check if new studies have been published that could be added to the existing studies in the review. In this review, we performed a new search and found new studies and, therefore, this is an update of the review published in 2002.

What is individual patient data? In this review we used individual patient data. This means we collected original research data for each participant from the original researchers who performed the studies. We used this information to perform our calculations.

Review question: What is the effect of NIPPV in people with COPD on blood gases, six‐minute walking distance, health‐related quality of life, lung function, respiratory muscle function and sleep efficiency.

Study characteristics: The evidence is current to August 2012. We found seven studies that reported the effects of NIPPV at home. Five of these studies looked at the effects after using NIPPV compared to regular treatment (without NIPPV) for at least three months. Two studies looked for a longer period of time, for at least 12 months. The mean age of all participants included in our meta‐analysis was 67 years. All studies included men and women, but 77% of participants were men. We used data from 245 people for our meta‐analysis.

Results: NIPPV during the night for 3 and 12 months in people with COPD who had raised levels of carbon dioxide had no clinically or statistically significant effect on gas exchange, six‐minute walking distance, health‐related quality of life, lung function, respiratory muscle strength and sleep efficiency. This means we found little or no difference in the outcomes.

Quality of the results: Because some trials had very small numbers of participants, our confidence in the quality of evidence is moderate when looking at the effects on gas exchange. All seven trials measured this outcome. Other outcomes were not always measured or available leading to a lower quality of evidence for the other outcomes such as six‐minute walking distance, health‐related quality of life, lung function, respiratory muscle function and sleep efficiency.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Nocturnal non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation compared with standard treatment for severe COPD.

| Nocturnal non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation compared with standard treatment for severe COPD | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with severe COPD Settings: home treatment Intervention: nocturnal non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation (nocturnal‐NIPPV)1 Comparison: standard treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard treatment | Nocturnal‐NIPPV | |||||

|

Arterial blood gas tension: PaO2 after 3 months mmHg |

The mean PaO2 in the control group was 53.2 mmHg | The mean PaO2 in the intervention group was 1.30 higher (95% CI ‐0.71 to 3.30)2 |

162 (6 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | ||

|

Arterial blood gas tension: PaCO2 after 3 months mmHg |

The mean PaCO2 in the control group was 52.9 mmHg | The mean PaCO2 in the intervention group was

2.50 lower (95% CI ‐5.28 to 0.29)2 |

162 (6 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | ||

|

6MWD after 3 months metres |

The mean 6MWD in the control group was 324 m | The mean 6WMD in the intervention group was 27.7 higher (95% CI ‐11.0 to 66.3) |

40 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | ||

|

Quality of life: SGQR after 12 months total score on a scale from 0 to 100 |

The mean SGRQ in the control group was 60.15 | The mean SGRQ Total score in the intervention group was 0.90 higher (95% CI ‐19.21 to 21.01) |

103 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,6 | Quality of life was not measured after 3 months in any study. Different questionnaires were used measuring quality of life after 12 months and only the SGRQ was measured by both long‐term studies with follow‐up of 12 months | |

|

Lung function: FEV1 after 3 months litres |

The mean FEV1 in the control group was 0.82 L | The mean FEV1 in the intervention group was0.01 lower (95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.07)7 |

83 (5 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk was the mean control group risk across studies. 6MWD: 6‐minute walking distance; CI: confidence interval; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; NIPPV: non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation; PaCO2: arterial carbon dioxide tension; PaO2: arterial oxygen tension; SGRQ: total score on the St. George's respiratory questionnaire. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Nocturnal non‐invasive ventilation was delivered through nose masks in five studies and by either a nasal or full‐face mask in two studies.

2 There was no significant change in PaO2 or PaCO2 after 12 months.

3 The confidence intervals cross zero, therefore there was no difference and could include both possible benefit and harm.

4 The number of participants was low.

5 Scores are expressed as a percentage of overall impairment where 100 represents worst possible health status.

6 The number of trials was low.

7 There was no significant change in FEV1 after 12 months.

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. There are several therapeutic options to help people with COPD manage their symptoms, but to date, only smoking cessation and the provision of long‐term oxygen therapy to hypoxic patients have been shown to prolong life (Crockett 2001). Usually, treatment is with bronchodilators and anti‐inflammatory drugs (corticosteroids), although the latter is still controversial in people with COPD. When medication doses are optimal and people still have dyspnoea or an impaired exercise tolerance, pulmonary rehabilitation can be added to medical therapy (Lacasse 2006). In people with more severe COPD, bronchoscopic lung volume reduction (Slebos 2012), lung volume reduction surgery (Cooper 1997), and, in extreme cases, lung transplantation (Orens 2006), can be considered. In people with COPD with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure nocturnal non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation (nocturnal‐NIPPV) might be beneficial.

Description of the intervention

In non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV), the person receives ventilatory support through a non‐invasive interface, such as a nasal mask, full‐facemask or helmet. NIPPV is currently applied as evidence‐based therapy in people with COPD admitted to hospital with acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to an exacerbation. It has been shown that NIPPV reduces hospital deaths and complications associated with treatment and length of hospital stay (Ram 2004). NIPPV during an acute exacerbation is often applied intermittently or continuously for a few days to reduce the (life‐threatening) ventilatory failure, after which the person is weaned from ventilation and treatment is ended. Chronic nocturnal‐NIPPV, however, entails the use of NIPPV at home during the night for a longer period. Currently there is much discussion about the need for NIPPV in COPD, mainly because conflicting results have been published (Rossi 2000). There is consensus, but with little supportive evidence, that people with COPD who have substantial daytime hypercapnia and superimposed nocturnal hypoventilation are most likely to benefit from NIPPV (Hill 2004).

How the intervention might work

Several theories exist as to why nocturnal‐NIPPV might be beneficial. First, nocturnal‐NIPPV might rest chronically fatigued muscles. Periods of rest may lead to recovery of the inspiratory muscle function, thereby leading to an increased muscle strength and endurance capacity of the respiratory muscles during the daytime (Ambrosino 1990). Second, nocturnal‐NIPPV has been shown to improve sleep time and efficiency (Meecham 1995), as people with severe COPD can experience poor sleep quality due to sleep‐disordered breathing with episodes of hypoventilation associated with desaturation. Third, nocturnal‐NIPPV may ameliorate nocturnal hypoventilation and allow the respiratory centre to be reset. In this way nocturnal‐NIPPV may reduce daytime hypercapnia (Elliott 1991). Fourth, it is postulated that nocturnal‐NIPPV decreases hyperinflation leading to an improvement in respiratory mechanics, such as an increase in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and a decrease in residual volume (Duiverman 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite all these theories, the effect of nocturnal‐NIPPV in people with stable severe COPD remains unclear and needs further investigation. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2002. Since then, more studies have been reported, making an update necessary. As in 2002, we performed a systematic review and meta‐analysis based on individual patient data (IPD). With IPD, we collected original research data for each participant from the original researchers for data checking, validation and re‐analysis. This gives an advantage over the conventional meta‐analysis based on summary statistics from published papers as more or different analyses are possible. IPD meta‐analyses have greater power, enabling investigation of additional hypothesis related to individual characteristics, for example within subgroups or treatment across trials, or both.

Objectives

To assess the effects of nocturnal‐NIPPV at home via nasal mask or face mask in people with stable COPD by using a meta‐analysis based on IPD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in people with stable COPD comparing nocturnal‐NIPPV at home plus standard therapy with standard therapy alone.

Types of participants

People with COPD according to the guidelines of American Thoracic Society (ATS 1995).

Types of interventions

NIPPV, applied through a nasal or face mask, for at least five hours during the night, for at least three consecutive weeks. Participants also received their usual standard COPD therapy, which comprised supplemental oxygen, bronchodilators, theophylline and corticosteroids.

The intervention in the control group was standard therapy alone. The control group did not receive nocturnal‐NIPPV.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Arterial blood gas tensions (partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the blood (PaCO2), partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PaO2)).

Six‐minute walking distance (6MWD).

Health status (health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) measurements).

Secondary outcomes

Lung function (FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC)).

Respiratory muscle function (muscle strength, including maximal inspiratory pressure (PImax)).

Sleep efficiency (time asleep as percentage of total time in bed.

Dyspnoea.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials from the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register (CAGR), which is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator for the Group. The Register contains trial reports identified through systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (see Appendix 1 for further details).

For the original version of this review we carried out a search on all COPD records in the Register using the terms: nasal ventilat* OR positive pressure OR NIPPV. For this update, a search was done in all COPD records in the Register using the following search string: (nasal OR mechanical OR noninvasive OR non‐invasive or "non invasive" or positive OR intermittent OR bi‐level OR "bi level" OR airway* OR controlled OR pressure OR support AND (ventilat*)) OR (NIPPV).

We conducted this most recent search in August 2012.

Searching other resources

We searched the bibliographies of each RCT for additional papers that may have contained RCTs. We contacted authors of identified RCTs for other published and unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the 2002 version of this review, two review authors (PJW, RSG) independently assessed all identified abstracts and for the 2013 update this was done by PJW and FMS. When we selected an abstract, full papers were retrieved and read in detail by the same two review authors and disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third review author.

Data extraction and management

After identification of studies, we contacted trial authors to ask for the IPD including anthropometric data and follow‐up data of the identified outcome variables. We requested missing data from the included primary studies from the authors. We checked supplied data against study publications after which we copied raw data from all included studies to one main database.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (FMS and PJW) assessed risk of bias of each study independently (for details see 'Risk of bias' table in Characteristics of included studies). We used criteria for assessment of risk of bias as provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We considered potential for bias using the following domains:

sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants, personnel and outcome measures;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting; and

other sources of bias.

We judged each domain as 'high', 'low' or 'unclear' risk of bias. If insufficient details were reported, the judgement was 'unclear' of risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

The principal investigators of all the trials included in the meta‐analysis kindly provided the individual data for each of their study subjects. We therefore conducted an individual data meta‐analysis. We expressed study outcomes in the same natural units across the trials. For each individual and for each outcome, we calculated an absolute difference in score that defined treatment effect. An overall treatment effect (mean difference and associated 95% confidence interval (CI)) was obtained from the difference in scores under each study condition (NIPPV minus controls). Different proportions of participants contributed to the different outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

In the case of cross‐over trials, we considered only the first study period (prior to the cross‐over).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted trialist and obtained IPD for all trials.

Assessment of heterogeneity

To consider the homogeneity among trials, a random factor was defined in the statistical models. Statistical significance (P value < 0.05) in the test of homogeneity suggested that the observed difference in the treatment effects was in part attributable to the study effect.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to inspect a funnel plot visually if we were able to meta‐analyse 10 or more trials for an outcome.

Data synthesis

We analysed IPD using a linear mixed model to compare the treatment effects. Treatment and time of follow‐up (3 and 12 months) were analysed with interaction terms as fixed factors. We performed all the analyses using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Caru, NC).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We considered subgroup analyses if sufficient numbers of studies and a large enough sample size were to be included in the analysis and if we found significant heterogeneity among the outcomes of the trials. We identified a priori potential sources of heterogeneity among the primary and secondary outcomes. We postulated the following sources of heterogeneity:

the more hypercapnic patients might benefit more from NIPPV;

the benefits of NIPPV might be greater among those who used it for longer periods;

people who received higher levels of inspiratory airway pressure (IPAP) might have a greater benefit of NIPPV.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies.

Results of the search

The search conducted up to August 2012 identified 687 records of which we retrieved 17 full‐text papers for further examination. We reduced the publications to 14 potentially eligible papers. We excluded five studies for the following reasons: not randomised (Clini 1998; Kamei 1999); duration of NIPPV too short (less than four hours per night and at daytime) (Diaz 1999; Renston 1994); training of NIPPV too short (less than three weeks) (Lin 1996). One study is awaiting classification as the authors failed to respond to clarify important issues (Xiang 2007). This update identified three new trials (Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009; Sin 2007), and together with the four trials from the original review (Casanova 2000; Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Strumpf 1991), we included seven studies in the meta‐analysis.

Included studies

Seven studies met the inclusion criteria for the review (Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; Gay 1996; McEvoy 2009; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007; Strumpf 1991). The Characteristics of included studies table shows full details of the included studies. Five studies provided data on NIPPV after three months and are classified as 'short term' (Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007), while two studies provide data after 12 months and are defined as 'long term' (Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009). We obtained IPD for each of these studies from the trial authors. We provided summary details below.

Trial design

Five studies were parallel in design (Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; Gay 1996; McEvoy 2009; Sin 2007) and two were cross‐over in design (Meecham Jones 1995; Strumpf 1991).

Participants

The seven included studies were based in different countries: Spain (Casanova 2000), Italy (Clini 2002), USA (Gay 1996; Strumpf 1991), Australia (McEvoy 2009), UK (Meecham Jones 1995), and Canada (Sin 2007). Five studies compared nocturnal‐NIPPV with standard treatment (Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009; Meecham Jones 1995; Strumpf 1991), and two studies compared nocturnal‐NIPPV with sham treatment in the form of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at 2 and 4 cm H2O (Gay 1996; Sin 2007). Nocturnal‐NIPPV was delivered through a nasal mask in five studies (Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Strumpf 1991), and by a either a nasal or full‐face mask in two studies (McEvoy 2009; Sin 2007). The mean age of all participants included in the IPD meta‐analysis was 67 years. All studies included men and women; 77% were men. Mean FEV1 was 0.73 L and mean PaCO2 was 53 mmHg. Mean IPAP for the short‐term studies was 14.7 cm H2O and for the long‐term studies was 13.6 cm H2O. Nocturnal‐NIPPV was applied for a mean of 6.7 hours in the short‐term studies and 6.6 hours in the long‐term studies.

Funding of trial

Six studies were funded by their National Respiratory Society/Foundation (Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; Gay 1996; McEvoy 2009; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007), from which two were also partly funded by an industrial company (Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009). One study was funded by an industrial company alone (Strumpf 1991).

Excluded studies

The Characteristics of excluded studies table provides full details of the excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

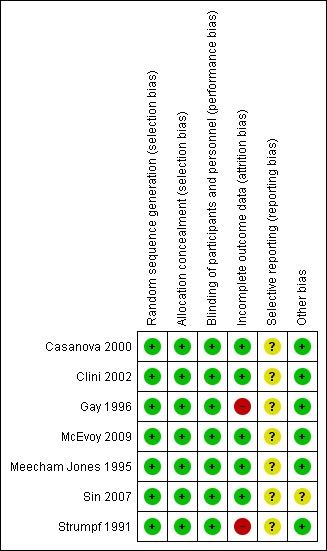

The Characteristics of included studies table provides details of risk of bias in the included studies. Figure 1 shows a summary of our risk of bias judgements across studies.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

All studies were described as randomised and described the method of randomisation adequately. Allocation concealment was also deemed to be adequate in all studies, four of them describing a centralised randomisation office or independent person. In the other three cases, sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes were used.

Blinding

Given the nature of the intervention it can be difficult to blind participants; however, two studies used a sham‐device (Gay 1996; Sin 2007). In one study, personnel were also blinded for the treatment allocation making this the only study that we could classify as a low risk of bias in this area (Sin 2007). Three studies had blinding for all physiological measurements (Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; Strumpf 1991), two had no blinding (McEvoy 2009; Meecham Jones 1995), and one was unclear (Gay 1996). However, we judged that outcome measurement was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding for personnel and, therefore, overall we judged all studies as low risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

In one of the cross‐over studies, only seven out of the 19 randomised participants completed both arms (Strumpf 1991). Another study reported that four out of seven participants randomised to NIPPV completed the trial, as opposed to all six in the sham group (Gay 1996). Both studies were classified as high risk of attrition bias. Two other studies also had dropouts and did not perform intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses but as numbers due to intolerance were small these studies were classified as low risk (Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007). The three remaining studies all reported ITT analyses as well as per‐protocol‐analyses (or stated that "Inclusion of the patients who did not complete the trial (intent to treat) did not affect any of the outcomes") and were therefore considered as low risk of bias (Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009). In addition, in the long‐term studies, reasons for missing data were not substantially different between both groups, for example; not being able to come for re‐testing due to a worsening of the disease (Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009).

Selective reporting

We could not find the original protocols to check if the prespecified outcomes were all reported in the articles, so in this area the risk of bias was unclear. However, all outcomes listed in the methods section of the studies were reported in the results section.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not find any other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Table 2 shows the results of the meta‐analysis based on IPD. There is a difference between the number of participants included in the studies and the number included in the meta‐analysis. There were some dropouts in most studies, for the short‐term follow‐up this was often due to intolerance of the nose mask, intercurrent infections or participants no longer meeting the inclusion criteria after a stabilisation period. In both studies looking at long‐term effects, this was often due to progression of the disease and reluctance of participants to return to hospital for follow‐up measurements. Finally, not all parameters were measured in all participants and, therefore, there is a difference in number of participants per outcome. In total, 245 participants were included in the IPD meta‐analysis.

1. Results of meta‐analysis individual patient data.

| Outcomes | Trial | Number (nocturnal‐NIPPV/control) | Tx Effect* | 95% CI |

Homogeneity of Tx Effect, P Value |

| PaO2 (3 months) | Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007; Strumpf 1991 | 79/83 | 1.30 | ‐0.71 to 3.30 | 0.4787 |

| PaO2 (12 months) | Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009 | 62/56 | ‐1.77 | ‐8.60 to 5.07 | 0.2412 |

| PaCO2 (3 months) | Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007; Strumpf 1991 | 79/83 | ‐2.50 | ‐5.28 to 0.29 | 0.2607 |

| PaCO2 (12 months) | Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009 | 62/56 | ‐0.96 | ‐3.55 to 1.64 | 0.8290 |

| 6MWD (3 months) | Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007 | 21/19 | 27.7 | ‐11.0 to 66.3 | 0.5662 |

| 6MWD (12 months) | Clini 2002 | 25/21 | 3.2 | ‐49.7 to 56.1 | ‐ |

| SGRQ Total (12 months) | Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009 | 50/53 | 0.90 | ‐19.21 to 21.01 | 0.0288 |

| FEV1 (3 months) | Casanova 2000; Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007; Strumpf 1991 | 42/41 | ‐0.01 | ‐0.09 to 0.07 | 0.2413 |

| FEV1 (12 months) | Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009 | 63/62 | ‐0.01 | ‐0.07 to 0.04 | 0.7445 |

| FVC (3 months) | Casanova 2000; Clini 2002; Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007; Strumpf 1991 | 42/40 | 0.00 | ‐0.13 to 0.14 | 0.9570 |

| FVC (12 months) | Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009 | 63/62 | 0.04 | ‐0.12 to 0.20 | 0.4510 |

| PImax (3 months) | Casanova 2000; Gay 1996; Strumpf 1991 | 24/24 | 4.87 | ‐1.48 to 11.21 | 0.5538 |

| PImax (12 months) | Clini 2002 | 29/23 | ‐2.31 | ‐9.50, 4.89 | ‐ |

| PEmax (3 months) | Casanova 2000; Gay 1996; Strumpf 1991 | 24/24 | 22.09 | ‐23.53 to 67.70 | 0.0002 |

| Sleep efficiency (3 months) | Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Strumpf 1991 | 13/11 | ‐9.11 | ‐38.09 to 19.86 | 0.0022 |

6MWD: 6‐minute walking distance; CI: confidence interval; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC: forced vital capacity; NIPPV: non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation; PaCO2: arterial carbon dioxide tension; PaO2:arterial oxygen tension; PEmax: maximal expiratory pressure; PImax: maximal inspiratory pressure; SGRQ‐Total: total score on the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire; Tx effect: treatment effect.

* An overall treatment effect (mean difference and associated 95% CI) was obtained from the difference in scores under each study condition (NIPPV minus controls). Individual patient data were analysed using a linear mixed model to compare the treatment effects. Treatment and time of follow‐up (3 and 12 months) were analysed with interaction terms as fixed factors. To consider the homogeneity among trials, a random factor was defined in the statistical models. Statistical significance (P value < 0.05) in the test of homogeneity suggested that the observed difference in the treatment effects was in part attributable to the study effect.

Arterial blood gas tensions

Three‐month follow‐up: all five short‐term studies contributed data towards this outcome (Casanova 2000; Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007; Strumpf 1991), as well as the Italian long‐term study (Clini 2002), which also provided data after three months. In total, 162 participants were analysed for blood gases. The 95% CI of PaO2 and PaCO2 included zero, hence they were not statistically significant. PaCO2 did show a trend towards significance with the 95% CI only just exceeding zero (mean difference (MD) ‐2.50, 95% CI ‐5.28 to 0.29).

Twelve‐month follow‐up: two studies (Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009), with 118 participants gathered data for this outcome. There was no significant difference in PaO2 and PaCO2 between standard care and NIPPV groups after 12 months (PaO2 MD ‐1.77, 95% CI ‐8.60 to 5.07; PaCO2 MD ‐0.96, 95% CI ‐3.55 to 1.64).

Six‐minute walking distance

Three‐month follow‐up: three studies with 40 participants measured 6MWD (Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007). Meta‐analysis showed a moderate treatment effect on 6MWD (MD 27.7, 95% CI ‐11.0 to 66.3), but this difference was not statistically different. Exercise endurance was reported by one study and determined by measuring treadmill walking time and could not be included in the meta‐analysis (Strumpf 1991).

Twelve‐month follow‐up: as only one study measured 6MWD after 12 months meta‐analysis was not possible (Clini 2002).

Health status

Three‐month follow‐up: only one study measured HRQoL after three months using the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire making meta‐analysis impossible (Meecham Jones 1995).

Twelve‐month follow‐up: Both long‐term studies measured HRQoL in 103 participants after 12 months using three different questionnaires (Short Form‐36 item (SF‐36) questionnaire by McEvoy 2009; Maugeri Respiratory Failure questionnaire‐28 by Clini 2002; St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire by Clini 2002 and McEvoy 2009), making it possible to only combine results for the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. The overall treatment effect was very small and was not significant (MD 0.90, 95% CI ‐19.21 to 21.01) and was found to be heterogeneous (P value = 0.03).

Lung function

Three‐ month follow‐up: all five short‐term studies with 83 participants provided data for FEV1 and FVC (Casanova 2000; Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Sin 2007; Strumpf 1991). Very small and non‐significant results were found for FEV1 (MD ‐0.01 L, 95% ‐0.09 to 0.07) and no effects were found for FVC (MD 0.00 L, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.14) after three months.

Twelve‐month follow‐up: both long‐term studies measured FEV1 and FVC in 125 participants after 12 months (Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009). The 95% CIs of FEV1 and FVC included zero (FEV1 MD ‐0.01 L, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.04; FVC MD 0.04 L, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.20), hence they were not statistically significant.

Respiratory muscle function

Three‐month follow‐up: three studies with 48 participants provided data for PImax and PEmax (Casanova 2000; Gay 1996; Strumpf 1991). The improvement in PImax was not statistically different (MD 4.87 cm H2O, 95% CI ‐1.48 to 11.21). PEmax showed a non‐significant improvement after three months NIPPV (MD 22.09 cm H2O, 95% CI ‐23.53 to 67.70) but with significant heterogeneity. The 95% CI was very wide, probably due to the small number of trials and consequently participants, and therefore we did not perform subgroup analyses.

Twelve‐month follow‐up: as only one study reported data on PImax (Clini 2002), and none on PEmax, no meta‐analyses were undertaken for these outcomes.

Sleep efficiency

Three‐month follow‐up: three studies with 24 participants provided data for sleep efficiency (Gay 1996; Meecham Jones 1995; Strumpf 1991) showing a small negative effect after three months (MD ‐9.11, 95% CI ‐38.09 to 19.86). This effect was heterogeneous. The study by Strumpf et al with only seven participants, reported a very broad 95% CI (MD 25.4, 95% CI ‐69.17 to 70.4). Subgroup analysis was not performed due to the low number of trials.

Twelve‐month follow‐up: sleep quality was measured differently by both long‐term studies. One reported on sleep efficiency by measuring time asleep as percentage of total time in bed (McEvoy 2009), but only performed follow‐up measurements in the NIPPV group. The other study also measured sleep quality but by means of a semi‐qualitative multipoint scale of 1 to 4 (Clini 2002). No meta‐analyses could be performed.

Dyspnoea

Three‐month follow‐up: dyspnoea was measured in two studies, but as they were measured with different scales (the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale and Borg scale by Casanova 2000 or Transitional Dyspnea Index (TDI) by Strumpf 1991), data could not be combined.

Twelve‐month follow‐up: one study (Clini 2002) measured dyspnoea after 12 months by means of a 6‐point MRC score. No meta‐analysis could be performed.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this update, IPD from three new studies were added to the original review (Wijkstra 2002), and two of these studies were conducted over 12 months, which means we now have some long‐term data on which to base our conclusions, including long‐term information on quality of life outcomes. Nocturnal‐NIPPV at home for at least three months in hypercapnic patients with stable COPD had no consistent clinically or statistically significant effect on gas exchange, exercise tolerance, lung function, respiratory muscle strength or sleep efficiency. Meta‐analysis of the two new long‐term studies did not show significant improvements in blood gases, HRQoL or lung function after 12 months of NIPPV.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In this meta‐analysis, we did not find statistically significant effects in any included outcomes. By adding data of PaCO2 after three months from two studies in this update, the improvement of 2.5 mmHg was still not significantly different but the CIs now only just exceeded zero. The small sample size precludes a definitive statement regarding the clinical implications of NIPPV, other than stating that at present there is insufficient evidence to support its widespread use.

Although the improvement of 27.7 m in the 6MWD is not statistically significant, it could be clinically significant as it does reach the clinically minimal important difference of 26 m (Puhan 2011). This meta‐analysis of 6WMD after three months, however, was only based on 40 participants and although not contributing to the meta‐analysis, the long‐term study of Clini 2002 looking at effects on 6MWD after 12 months of NIPPV only found a very small improvement of 3.2 m (95% CI ‐49.7 to 56.1) in 46 participants.

The upper limit of the CI of 66 m for the 6MWD in the meta‐analysis suggests that it remains possible that NIPPV has beneficial effects on walking in at least some people, but it is not possible to identify these people a priori. Additional studies with larger sample sizes that address participant selection, ventilator settings, training and NIPPV compliance should clarify the role of this treatment.

Not all outcomes could be combined because of measurements with different scales. Dyspnoea was measured in three studies, but as this was measured with the 5‐point MRC scale (Casanova 2000) and 6‐point MRC scale (Clini 2002), Borg (Casanova 2000), or TDI (Strumpf 1991) and different lengths of follow‐up, data could not be combined. The same applied to HRQoL; three studies examined this outcome but all used different questionnaires ranging from the more generic SF‐36 questionnaire (McEvoy 2009) and the (lung) disease specific St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009; Meecham Jones 1995) to the Maugeri Respiratory Failure questionnaire‐28 (MRF‐28) (Clini 2002), designed for people with respiratory failure. For future studies, it would be of great benefit if the same questionnaires were to be used making comparison and pooling of data possible. The effect of NIPPV may not be captured by the HRQoL questionnaires currently analysed. Several studies have shown good reliability and validity of the Severe Respiratory Insufficiency (SRI) questionnaire and the MRF‐28, specifically for people with COPD with hypercapnic respiratory failure (Duiverman 2008; Windisch 2003). It has been suggested to use both these questionnaires, as the SRI focuses more on psychological aspects and the MRF‐28 focuses on restrictions of daily living. But moreover, a large trial also looking at the effect of NIPPV on survival, exacerbation frequency and admissions is needed.

Quality of the evidence

Seven (three new to this update) RCTs with individual data from 245 people were included in this systematic review. Meta‐analysis was performed when trials used similar outcome measures. Short‐term trials were analysed as one group, measuring effects of NIPPV after three months. Long‐term trials comprised the second group, measuring effects of NIPPV after 12 months. All studies described how randomisation was performed and described adequate allocation concealment. Mainly the short‐term studies had few participants (between 7 and 36 participants) and sometimes showed large CIs for some outcome measures such as PImax (Strumpf 1991). Two studies show a high dropout rate after randomisation because people were not able to tolerate NIPPV (Gay 1996; Strumpf 1991). Only results from the completers were reported, which could make outcomes susceptible to selection bias. In the other studies, dropout due to non‐tolerance was considered small. The two larger studies with long‐term follow‐up had quite large dropout rates but mainly due to progression of the disease and unwillingness to repeat tests; these were similar amounts between groups. Both studies performed ITT analysis and per‐protocol analysis. In this systematic update we only included complete data.

The meta‐analysis in this review was performed based on IPD. Treatment effects can, therefore, be seen as more conservative (with wider CIs). They take into account not only interstudy variation, but also intrastudy variation.

Potential biases in the review process

Limitations regarding the setup of the meta‐analyses

The design of this meta‐analysis included only studies in which nocturnal‐NIPPV was applied for at least five hours per night. This excluded two studies that reported beneficial effects from NIPPV administered for two hours during the day (Diaz 1999; Renston 1994). In keeping with the application of mechanical ventilatory support for people with thoracic restriction or neuromuscular conditions, we considered night‐time ventilation to be the most appropriate clinical approach and reasoned that several hours would be required to achieve therapeutic goals. Furthermore, a minimum duration of three weeks was chosen, as from our own clinical experience we were aware that it might take up to two weeks just for mask fitting, adjustment and patient familiarisation with non‐invasive ventilation. Therefore, one study in which NIPPV was assessed for only two weeks was excluded from the analysis (Lin 1996).

Limitations regarding the included studies

We included RCTs that determined the effects of NIPPV versus normal medical treatment. However, it is questionable whether NIPPV with IPAP pressures below 14 cm H2O is enough to improve ventilation. As the most appropriate NIPPV settings have yet to be established, it is unclear whether pressures of 10 to 14 cm H2O are the optimal pressures for improving ventilation in people with COPD (Casanova 2000; Gay 1996). Since the 1990s, several non‐randomised trials studied a new form of NIPPV aimed at maximally reducing PaCO2 levels by means of high IPAP pressures (Windisch 2009). This form is called high‐intensity NIPPV (HI‐NIPPV) where pressures are carefully increased from 20 H2O up to 40 H2O depending on patient comfort and tolerance. These studies all had a mean IPAP of around 30 H2O and showed improvements in blood gases and alveolar ventilation during spontaneous breathing, and also improvements in lung function and HRQoL. One randomised controlled cross‐over trial subsequently followed comparing six weeks of HI‐NIPPV (mean IPAP 29 H2O in controlled mode) to six weeks of low‐intensity NIPPV (mean IPAP 15 H2O in assist mode) (Dreher 2010). Thirteen people completed the trial and a mean treatment effect on PaCO2 of 9.2 mmHg (95% CI ‐13.7 to ‐4.6) in favour of HI‐NIPPV was shown, as well as an improved FEV1, FVC and HRQoL as assessed by the SRI. Somewhat surprisingly, participants showed a higher compliance in the HI‐NIPPV group. One randomised cross‐over study of 15 people was performed to investigate the acute physiological changes during 30 minutes of both forms of NIPPV in stable COPD (Lukácsovits 2012). Significant improvements in PaCO2 during HI‐NIPPV (mean IPAP 28 H2O) compared to low NIPPV (mean IPAP 18 H2O) were also found in this study, However, the decrease in cardiac output was significantly more pronounced with HI‐NIPPV, leading the authors to speculate on possible limitations of this method for people with pre‐existing cardiac disease.

One published, long‐term RCT that compared the effects of NIPPV, not to standard care, but in addition to rehabilitation (Duiverman 2011), showed a significant decrease in PaCO2 in the NIPPV plus rehabilitation group as compared to the rehabilitation only group. Interestingly, although mean levels of IPAP after three months were 20 cm H2O and after two years were 23 cm H2O, there was no relationship identified between the change in PaCO2 and the level of IPAP (or with the inspiratory pressure difference (IPAP minus EPAP)). Change in PaCO2 after three months did correlate with baseline PaCO2 or with the number of hours of NIPPV use per day.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In 2007, one systematic review on NIPPV in people with stable COPD was published (Kolodziej 2007). An important difference with this systematic review is the inclusion of non‐RCTs. They found improvements in blood gasses, hyperinflation and work of breathing, but only in a combined analysis of non‐randomised trials with evident heterogeneity. This heterogeneity was probably the result of including studies with different lengths of follow‐up, usages per day and types of ventilation (during the day or at night).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Nocturnal‐non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation at home for 3 and 12 months in hypercapnic patients with COPD had no clinically or statistically significant effect on gas exchange, exercise tolerance, quality of life, lung function, respiratory muscle strength or sleep efficiency.

Implications for research.

Future research should focus on adequate patient selection, ventilator settings, training and length of ventilation, as well as exacerbation frequency, admissions to hospital and survival. During ventilation, people should be monitored carefully, to observe more precisely the changes that are occurring with non‐invasive ventilation. Long‐term non‐invasive ventilation for people with COPD should only be started in the context of a clinical trial, preferably with agreed upon common outcome parameters.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 June 2014 | Amended | PLS title amended |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2001 Review first published: Issue 2, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 February 2013 | New search has been performed | New literature search done |

| 28 January 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | A new search was performed which identified 3 new eligible studies (Clini 2002; McEvoy 2009; Sin 2007). One trial is listed as 'awaiting classification' until we can clarify the methods used in their study. The review has been re‐written and there has been a change to the list of authors and the review now also contains long‐term data (after 12 months). |

| 13 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 2 January 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank the authors of the seven included studies; Ciro Casanova, Enrico Clini, Peter Gay, Doug McEvoy, Jeffrey Meecham Jones, Don Sin and David Strumpf (Carol Carlisle and Nicholas Hill) who provided individual patient data for this meta‐analysis. We also wish to acknowledge the assistance provided by Serge Simard, biostatistician and the Cochrane Airways Review Group (for the original review: Steve Milan and Toby Lasserson, for the update: Emma Welsh and Susan Ann Hansen) and the statistical help from Dr. Chris Cates.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Sources and search methods for the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register (CAGR)

Electronic searches: core databases

| Database | Frequency of search |

| CENTRAL (T he Cochrane Library) | Monthly |

| MEDLINE (Ovid) | Weekly |

| EMBASE (Ovid) | Weekly |

| PsycINFO (Ovid) | Monthly |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) | Monthly |

| AMED (EBSCO) | Monthly |

Handsearches: core respiratory conference abstracts

| Conference | Years searched |

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) | 2001 onwards |

| American Thoracic Society (ATS) | 2001 onwards |

| Asia Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR) | 2004 onwards |

| British Thoracic Society Winter Meeting (BTS) | 2000 onwards |

| Chest Meeting | 2003 onwards |

| European Respiratory Society (ERS) | 1992, 1994, 2000 onwards |

| International Primary Care Respiratory Group Congress (IPCRG) | 2002 onwards |

| Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) | 1999 onwards |

MEDLINE search strategy used to identify trials for the CAGR

COPD search

1. Lung Diseases, Obstructive/

2. exp Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/

3. emphysema$.mp.

4. (chronic$ adj3 bronchiti$).mp.

5. (obstruct$ adj3 (pulmonary or lung$ or airway$ or airflow$ or bronch$ or respirat$)).mp.

6. COPD.mp.

7. COAD.mp.

8. COBD.mp.

9. AECB.mp.

10. or/1‐9

Filter to identify RCTs

1. exp "clinical trial [publication type]"/

2. (randomised or randomised).ab,ti.

3. placebo.ab,ti.

4. dt.fs.

5. randomly.ab,ti.

6. trial.ab,ti.

7. groups.ab,ti.

8. or/1‐7

9. Animals/

10. Humans/

11. 9 not (9 and 10)

12. 8 not 11

(The MEDLINE strategy and RCT filter are adapted to identify trials in other electronic databases)

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Casanova 2000.

| Methods | Randomised, parallel, controlled study | |

| Participants | 52 people with COPD, FEV1 0.85 L, PaCO2 51 mmHg. Raw data for 36 people with COPD, FEV1 0.84 L, PaCO2 51 mmHg | |

| Interventions | 26 people received standard care plus nocturnal‐NIPPV (IPAP 12 to 14, EPAP 4) for 12 months, while the other 26 continued optimal standard care | |

| Outcomes | After 3 months: BGA, lung function, dyspnoea (MRC and Borg scale), PImax/PEmax After 12 months: exacerbation rate, hospital admissions, intubations and mortality |

|

| Notes | Funding: supported in part by a grant from the Spanish Respiratory Society | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The 52 patients who met the study criteria were randomised by an independent office into two groups using a table of random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomised by an independent office using a table of random numbers" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants: no blinding for treatment Quote (from correspondence): "Blinded: for gas exchange and lung function" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Inclusion of the patients who did not complete the trial (intent to treat) did not affect any of the outcomes" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes listed in the Methods were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other source of bias |

Clini 2002.

| Methods | Randomised, parallel, controlled study | |

| Participants | 90 people with COPD randomised; FEV1 % predicted 29, PaCO2 55 mmHg. Raw data for 80 people with COPD, FEV1 0.75 L, PaCO2 56 mmHg | |

| Interventions | 43 people received standard care plus nocturnal‐NIPPV (IPAP 14, EPAP 2) for 24 months and 47 continued optimal standard care | |

| Outcomes | After 3 months: BGA, hospitalisations After 12 months: BGA, lung function, dyspnoea (MRC), 6MWD, PImax, sleep studies (4‐point scale), QoL (SGRQ and MRF‐28) and hospitalisation |

|

| Notes | Funding: this study was supported by AIPO (Italian Association of Hospital Pulmonologists) and Markos‐Mefar through Air Liquide Group Italia | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...a centralised randomisation was used" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Because of the small number of eligible patients in each centre, a centralised randomisation was used. Blocks were used to provide balanced groups in the overall enrolment (not inside each centre)" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants: no blinding for treatment Quote: "All physiological measurements were performed by personnel blind to treatment and not involved in the study" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Main parameters were evaluated both in terms of patient completers and of intention‐to‐treat" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes listed in the Methods were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other source of bias |

Gay 1996.

| Methods | Randomised, parallel, controlled study. | |

| Participants | 13 people with COPD randomised, FEV1 0.67 L, PaCO2 52 mmHg. Raw data for 10 people with COPD, FEV1 0.68 L, PaCO2 52 mmHg | |

| Interventions | 7 people received nocturnal‐NIPPV (IPAP 10, EPAP 2) for 3 months, while 6 received sham NIPPV (with maximal medical care) | |

| Outcomes | After 3 months: BGA, lung function, 6MWD, sleep study (sleep efficiency), PImax/PEmax | |

| Notes | Funding: this study was supported in part by Grant MOl RR 00585 from the National Institutes of Health, Public Health Service, and the Mayo Foundation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "By randomisation..." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote (from correspondence): "It was done with a sealed envelope randomisation technique" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants: blinded for intervention (as it was NIPPV versus sham) Personnel: unknown |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Final analysis was done with only the completers; 4 out of 7 people who were still using ventilation and all the 6 people in sham group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes listed in the Methods were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other source of bias |

McEvoy 2009.

| Methods | Randomised, parallel, controlled study | |

| Participants | 144 people with COPD randomised; FEV1 0.59 L, PaCO2 53.5 mmHg. Raw data 81 people with COPD, FEV1 0.65 L, PaCO2 54 mmHg | |

| Interventions | 72 people received standard care plus nocturnal‐NIPPV (IPAP 13, EPAP 5) for 24 months and 72 continued optimal standard care | |

| Outcomes | After 12 months: BGA, lung function, sleep studies (total sleep time in only NIPPV group), HRQoL (SGRQ and SF‐36), hospitalisation rates (days on trial:days in hospital rate), survival | |

| Notes | Funding: Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, Air Liquide Healthcare, Australian Lung Foundation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were randomly assigned..." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The central study coordinator generated a random sequence of treatment assignments that were stratified by centre and distributed in blocks of 10 sealed opaque envelopes to centres" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No blinding for participants, intervention or personnel |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "All primary analyses were conducted on an intention‐to‐treat basis. However, since a proportion of patients assigned to NIV treatment did not use the treatment regularly or abandoned it altogether after a time, a planned per protocol sub analysis was conducted comparing outcomes of patients in the treatment arm who used NIV consistently (defined as average > 4 hours per night) with patients in the control arm" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes listed in the Methods were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other source of bias |

Meecham Jones 1995.

| Methods | Randomised, controlled, cross‐over study | |

| Participants | 18 people with COPD randomised, FEV1 0.86 L, PaCO2 56 mmHg. Raw data 14 people with COPD, FEV1 0.84 L, PaCO2 56 mmHg | |

| Interventions | Nocturnal‐NIPPV (IPAP 18, EPAP 2) for 3 months, while the control group continued optimal medical care including long‐term oxygen | |

| Outcomes | After 3 months: BGA, lung function, 6MWD, HRQoL, sleep study (sleep efficiency) | |

| Notes | Funding: supported by a grant from the British Lung Foundation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was achieved with a previously generated randomised sequence" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote from correspondence: "The sequence was kept by another research fellow unconnected with the study and I was made aware of the randomisation as patients were recruited" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Fourteen of the 18 patients completed all stages of the study." Reasons for withdrawal for all 4 participants were mentioned. One patient did not tolerate NIPPV. Final analysis was done with the 14 completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes listed in the Methods were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other source of bias |

Sin 2007.

| Methods | Randomised, parallel, controlled study | |

| Participants | 23 people with COPD randomised; FEV1 0.86 L, PaCO2 44.2 mmHg. Raw data 17 people with COPD, FEV1 0.88 L, PaCO2 43 mmHg | |

| Interventions | 11 people received standard medical therapy plus nocturnal‐NIPPV (IPAP 16, EPAP 4) for 3 months while 12 people received standard medical therapy plus sham NIPPV | |

| Outcomes | After 3 months: BGA, lung function and 6MWD | |

| Notes | Funding: this project is supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (clinical trials), The Institute of Health Economics, and the University of Alberta Hospital Foundation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Recruited patients were randomly assigned to..." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization occurred at a central site by one individual who was unaware of patients' clinical status" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blind design. Participants were blind to intervention treatment (NIPPV versus sham) and: "All outcome measurements were performed and interpreted by personnel who were blinded to treatment allocation of patients" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Two out of eleven subjects refused any nocturnal therapy following randomisation and were excluded from the main analysis" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes listed in the Methods were reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | At baseline no significant differences except for FEV1, which was significantly higher in the group that received NIPPV |

Strumpf 1991.

| Methods | Randomised, controlled, cross‐over study | |

| Participants | 19 people with COPD randomised, FEV1 0.54 L, PaCO2 49 mmHg. Raw data 7 people with COPD, FEV1 0.54 L, PaCO2 46 mmHg | |

| Interventions | Nocturnal‐NIPPV (IPAP 15, EPAP 2) for 3 months, while the control group continued optimal medical care | |

| Outcomes | BGA, lung function, PImax/ PEmax, sleep study (sleep efficiency), walking test (treadmill walking time), dyspnoea (Transitional Dyspnea Index) | |

| Notes | Funding: supported in part by a grant from Respironics, Inc., Monroeville, Pennsylvania | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Using a randomised, crossover design..." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote (from correspondence): "Computer‐generated random number sequence placed in envelopes that were opened as patients were enrolled" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants: no blinding for treatment (cross‐over) Quote: "All physiological measurements were performed by personnel blind to treatment and not involved in the study" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Reasons for withdrawal from study were mentioned for every participant. 7 people withdrew due to intolerance, 5 of intercurrent illness. Final analysis in article was done with the 7 people who completed both arms |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes listed in the Methods were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other source of bias |

6MWD: 6‐minute walking distance; BGA: blood gas analysis; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life; MRC: Medical Research Council scale; MRF‐28: Maugeri Respiratory Failure questionnaire‐28; NIPPV: non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation; PaCO2: arterial carbon dioxide tension; PImax: maximal inspiratory pressure; PEmax: maximal expiratory pressure; QoL: quality of life; SF‐36: Short Form ‐ 36 items; SGRQ: St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Clini 1998 | The assignment of the participants to the 2 groups was not randomised |

| Diaz 1999 | Participants received NIPPV for 3 hours a day. We believe that NIPPV should be applied during the night for at least 5 hours per night |

| Kamei 1999 | The assignment of the participants to either NIPPV or long‐term oxygen therapy groups was not randomised |

| Lin 1996 | Participants received NIPPV for only 2 weeks. It is difficult to start NIPPV in people with COPD, therefore, it is necessary to determine the effects after a longer period so the participants can adjust to the ventilator |

| Renston 1994 | People received NIPPV for 2 hours a day for 5 day. We believe that NIPPV should be applied during the night for at least 5 hours per night. |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NIPPV: non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation.

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Xiang 2007.

| Methods | Randomised, parallel controlled study |

| Participants | 40 people with COPD |

| Interventions | Nocturnal‐NIPPV and long‐term oxygen therapy versus long‐term oxygen therapy alone for 2 years |

| Outcomes | BGA, lung function, dyspnoea, 6MWD, respiratory muscle score, mortality, hospital admissions, dropout rate, anxiety scores |

| Notes | The article was written in Chinese. This study probably meets the review eligibility criteria, but verifying how the study was conducted based on the English information available was not possible as authors did not respond to clarify important issues |

6MWD: 6‐minute walking distance; BGA: blood gas analysis; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NIPPV: non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation.

Differences between protocol and review

We selected three of the primary outcomes from the last update as our primary outcomes in consultation with the Cochrane Airways Group.

Contributions of authors

Update 2012: Struik and Wijkstra searched and reviewed relevant papers, collected IPD of the newly included RCTs, authors of the review. Lacasse: statistical analysis of IPD, co‐author of the review. Goldstein and Kerstjens: review development, co‐author of the review.

Original review: Wijkstra: searched and reviewed relevant papers, collected IPD of included RCTs, author of the review. Lacasse: statistical analysis of IPD, co‐author of the review. Guyatt: co‐author of the review. Goldstein: search and reviewing of relevant papers, co‐author of the review.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Casanova 2000 {published data only}

- Casanova C, Celli BR, Tost L, Soriano E, Abreu J, Velasco V, et al. Long‐term controlled trial of nocturnal nasal positive pressure ventilation in patients with COPD. Chest 2000;118(6):1582‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clini 2002 {published data only}

- Clini E, Sturani C, Rossi A, Viaggi S, Corrado A, Donner CF, et al. The Italian multicentre study on noninvasive ventilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. European Respiratory Journal 2002;3:529‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gay 1996 {published data only}

- Gay PC, Hubmayr RD, Stroetz RW. Efficacy of nocturnal nasal ventilation in stable, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during a three‐month controlled trial. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 1996;71(6):533‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McEvoy 2009 {published data only}

- McEvoy RD, Pierce RJ, Hillman D, Esterman A, Ellis EE, Catcheside PG, et al. Nocturnal non‐invasive nasal ventilation in stable hypercapnic COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2009;64(7):561‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meecham Jones 1995 {published data only}

- Meecham Jones D, Paul EA, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Nasal pressure support ventilation plus oxygen compared with oxygen therapy alone in hypercapnic COPD. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1995;152(152):538‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sin 2007 {published data only}

- Sin DD, Wong E, Mayers I, Lien DC, Feeny D, Cheung H, et al. Effects of nocturnal noninvasive mechanical ventilation on heart rate variability of patients with advanced COPD. Chest 2007;131(1):156‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Strumpf 1991 {published data only}

- Strumpf DA, Millman RP, Carlisle CC. Nocturnal positive pressure ventilation via nasal mask in patients with COPD. American Review of Respiratory Disease 1991;144:1234‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Clini 1998 {published data only}

- Clini E, Strurani C, Porta R. Outcome of COPD patients performing nocturnal non‐invasive mechanical ventilation. Respiratory Medicine 1998;92:1215‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diaz 1999 {published data only}

- Diaz O, Gallardo J, Ramos J, Torrealba B, Lisboa C. Non‐invasive mechanical ventilation in severe stable hypercapnic COPD patients: a prospective randomised clinical trial. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1999;159:A295. [Google Scholar]

Kamei 1999 {published data only}

- Kamei M. Effectiveness of noninvasive positive‐pressure ventilation for patients with chronic stable hypercapnic respiratory failure. Nihon Koyuki Gakkai Zasshi 1999;37(11):886‐92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lin 1996 {published data only}

- Lin CC. Comparison between nocturnal nasal positive pressure ventilation combined with oxygen therapy and oxygen monotherapy in patients with severe COPD. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1996;154:353‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Renston 1994 {published data only}

- Renston JP, DiMarco AF, Supinski GS. Respiratory muscle rest using nasal BiPAP ventilation in patients with stable severe COPD. Chest 1994;105(4):1053‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Xiang 2007 {published data only}

- Xiang PC, Ziang PC, Zhang X, Yang JN, Zhang EM, Gou WA, et al. The efficacy and safety of long term home noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in patients with stable severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases 2007;30(10):746‐50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Ambrosino 1990

- Ambrosino N, Montagna T, Nava S, Negri A, Brega S, Fracchia C, et al. Short term effect of intermittent negative pressure ventilation in COPD patients with respiratory failure. European Respiratory Journal 1990;3:502‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ATS 1995

- American Thoracic Society. Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1995;152:S77‐121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1997

- Cooper JD. The history of surgical procedures for emphysema. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 1997;63:312‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crockett 2001

- Crockett AJ, Cranston JM, Moss JR, Alpers JH. A review of long‐term oxygen therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory Medicine 2001;95:437‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dreher 2010

- Dreher M, Storre JH, Schmoor C, Windisch W. High‐intensity versus low‐intensity non‐invasive ventilation in patients with stable hypercapnic COPD: a randomised crossover trial. Thorax 2010;65(4):303‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Duiverman 2008

- Duiverman ML, Wempe JB, Bladder G, Kerstjens HA, Wijkstra PJ. Health‐related quality of life in COPD patients with chronic respiratory failure. European Respiratory Journal 2008;32:379‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Duiverman 2011

- Duiverman ML, Wempe JB, Bladder G, Vonk JM, Zijlstra JG, Kerstjens HA, et al. Two‐year home‐based nocturnal noninvasive ventilation added to rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a randomized controlled trial. Respiratory Research 2011;12:112. [DOI: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-112] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Elliott 1991

- Elliott MW, Mulvey DA, Moxham J, Green M, Branthwaite MA. Domiciliary nocturnal nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation in COPD: mechanisms underlying changes in arterial blood gas tensions. European Respiratory Journal 1991;4(9):1044‐52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hill 2004

- Hill NS. Noninvasive ventilation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory Care 2004;49(1):72‐87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kolodziej 2007

- Kolodziej MA, Jensen L, Rowe B, Sin D. Systematic review of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in severe stable COPD. European Respiratory Journal 2007;30(2):293‐306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lacasse 2006

- Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, Martin S. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lukácsovits 2012

- Lukácsovits J, Carlucci A, Hill N, Ceriana P, Pisani L, Schreiber A, et al. Physiological changes during low‐ and high‐intensity noninvasive ventilation. European Respiratory Journal 2012;39(4):869‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meecham 1995

- Meecham Jones DJ, Paul EA, Jones PW. Nasal pressure support ventilation plus oxygen compared with oxygen therapy alone in hypercapnic COPD. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1995;152:538‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Orens 2006

- Orens JB, Estenne M, Arcasoy S, Conte JV, Corris P, Egan JJ, et al. International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2006 update–a consensus report from the Pulmonary Scientific Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2006;25:745‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Puhan 2011

- Puhan MA, Chandra D, Mosenifar Z, Ries A, Make B, Hansel NN, et al. The minimal important difference of exercise tests in severe COPD. European Respiratory Journal 2011;37 Suppl:748‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ram 2004

- Ram FS, Picot J, Lightowler J, Wedzicha JA. Non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation for treatment of respiratory failure due to exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004104.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rossi 2000

- Rossi A, Hill NS. Non invasive ventilation has (not) been shown to be ineffective in stable COPD. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2000;161:688‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Slebos 2012

- Slebos DJ, Klooster K, Ernst A, Herth FJ, Kerstjens HA. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction coil treatment of patients with severe heterogeneous emphysema. Chest 2012;142(3):574‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Windisch 2003

- Windisch W, Freidel K, Schucher B, Baumann H, Wiebel M, Matthys H, et al. The Severe Respiratory Insufficiency (SRI) Questionnaire: a specific measure of health‐related quality of life in patients receiving home mechanical ventilation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2003;56:752‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Windisch 2009

- Windisch W, Haenel M, Storre JH, Dreher M. High‐intensity non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation for stable hypercapnic COPD. International Journal of Medical Sciences 2009;6(2):72‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Wijkstra 2002

- Wijkstra PJ, Lacasse Y, Guyatt GH, Goldstein RS. Nocturnal non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002878] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]