History

The diagnostic spectrum from rotator cuff tendinopathy through cuff tear arthropathy causes pain and disability that can result in surgical intervention [15]. In 1931, Codman and Akerman [5] proposed that degenerative changes of the tendons initiate rotator cuff tears. Subsequently, in 1949, Armstrong [1] proposed that mechanical impingement of the rotator cuff tendons under the acromion causes supraspinatus syndrome. Neer [21] also postulated that mechanical impingement was responsible for up to 95% of rotator cuff tears and reported successful treatment with anterior acromioplasty [20]. Regardless of the etiology, acromioplasty is commonly used as a surgical adjunct for the treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy and tears. In 1986, Bigliani and colleagues [3] were the first to classify acromial morphology and correlate it with rotator cuff tears. They described three types of acromion: Type I (flat), Type II (curved), and Type III (hooked) (Fig. 1). A Type IV acromion was later described as a convex acromion [28]. Bigliani et al. [3] and other authors [2, 6–8, 10, 13] have reported that Type III acromia have been associated with rotator cuff tears. Conversely, other authors have found no such correlation [23, 24]. Since Bigliani et al.’s [3] original description, there have been other attempts to quantify acromial morphology. Bigliani et al. [3] and Kitay [12] described the acromial slope, a measure of anterior acromial slope and the relationship between increased acromial slope and rotator cuff tears. In the same paper, Kitay [12] also described acromial tilt, the angle between a line drawn connecting the most posterior point of the inferior acromion to the most anterior point of the inferior acromion and a line drawn connecting the same most posterior point of the inferior acromion to the inferior tip of the coracoid process. Decreased acromial tilt was associated with rotator cuff tears [12]. Nyffeler et al. [22] described the acromial index, a ratio of the distance from the glenoid plane to the acromion divided by the distance from the glenoid plane to the lateral aspect of the humeral head. The authors observed that the acromion of patients with a rotator cuff tear appeared to have a more lateral extension, thus a greater acromial index, than that of patients with an intact cuff [22]. Most recently, the critical shoulder angle (CSA) was described, which not only includes acromial morphology but also considers glenoid morphology [16]. The authors observed patients with rotator cuff tears were more likely to have a CSA > 35° than a control group of patients without rotator cuff tears. Although there have been numerous attempts to find an association between rotator cuff tears and scapular morphology [2, 3, 12, 17, 18], there is no consensus as to the role of scapular morphology in the etiology of rotator cuff tears.

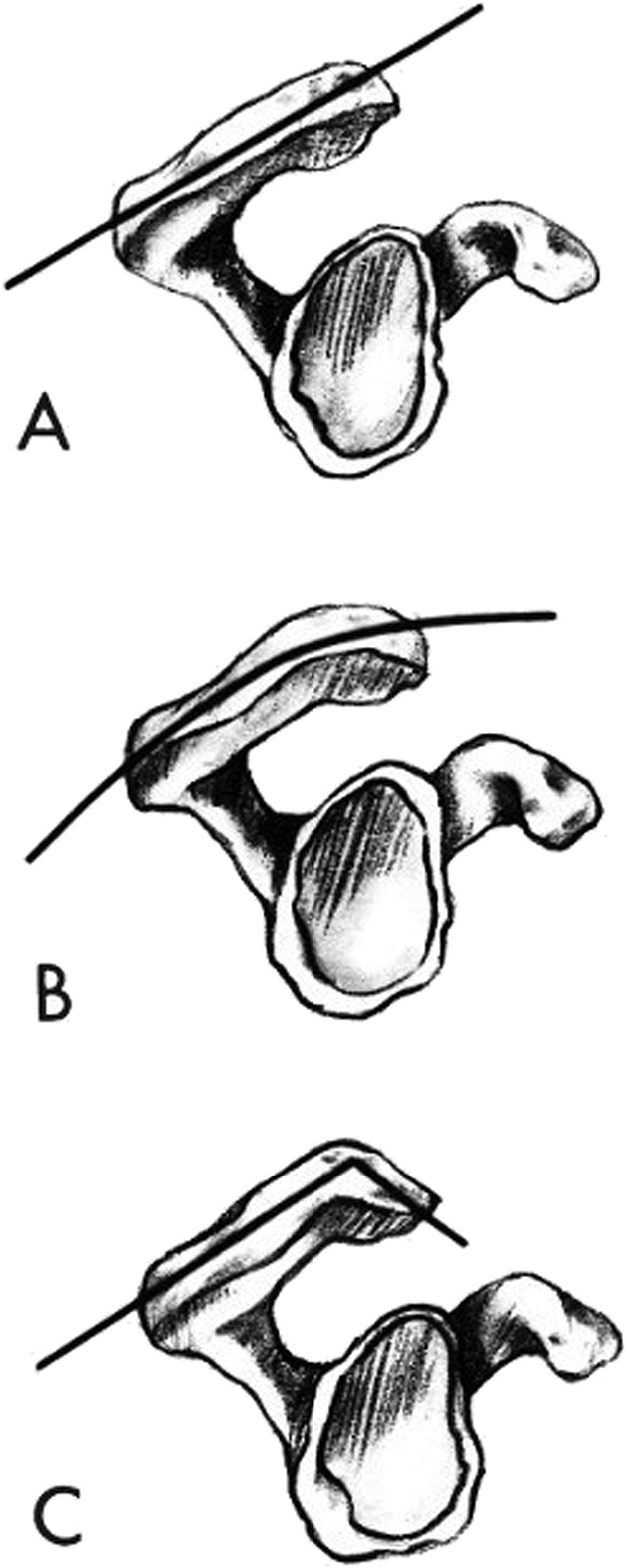

Fig. 1.

This diagram shows the Bigliani classification of acromial morphology: (A), Type I (flat); (B), Type II (curved); and (C), Type III (hooked). Reprinted with permission from Bright AS, Torpey B, Magid D, Codd T, McFarland EG. Reliability of radiographic evaluation for acromial morphology. Skeletal Radiol. 1997;26:718–721.

Purpose

The original purpose of the Bigliani classification [3] was to describe acromial morphology and determine whether it was associated with rotator cuff tears.

To our knowledge, the Bigliani classification of acromial morphology was the first classification system to try to define acromial morphology. One goal was to facilitate communication among clinicians and to support further research on the relationship between acromial morphology and rotator cuff tendinopathy. However, as we have already noted, this relationship has been questioned (particularly with respect to the concept of impingement syndrome) [2, 23, 24]. In addition, problems with reliability of the Bigliani classification [2, 4, 9, 31] have been reported. Taken together, these concerns should cause both clinicians and researchers to use the Bigliani classification with caution, if at all.

In the same publication, Bigliani et al. [3] aimed to determine if there was any correlation between acromial morphology and the presence of rotator cuff tears. Bigliani et al. [3] found that 69.8% of full-thickness rotator cuff tears had Type III acromia, 24.2% had Type II acromia , and 3% had Type I acromia. Further studies have reported conflicting results; some found correlations between acromial morphology and rotator cuff tears [3, 7, 13], and others did not [23, 24].

Later attempts to identify whether acromial morphology types were associated with impingement syndrome were made [2, 6], although this was not originally a purpose of the classification system. Two studies [2, 6] observed that there was no correlation between impingement syndrome and acromial morphology. Because of the proposed correlation between rotator cuff tears and Type III acromia, it was theorized that patients with Type III acromia may be at risk of having impingement syndrome [19].

Classification

In 1986, Bigliani et al. [3] described three distinct types of acromial morphology after taking lateral radiographs of 140 shoulders from 71 cadavers. They described Type I as flat, Type II as curved, and Type III as hooked (Fig. 1). No further attempt was made to further define the three different acromial morphology types.

Bigliani et al. [3] also observed that acromial morphology and rotator cuff tears were associated with two additional factors. There was an association between increasing acromial slope, which increased from Type I to Type III acromia, and rotator cuff tears, as well as between anterior acromial spurs and rotator cuff tears. Both observations have been verified by further research from several authors [2, 3, 9, 12].

Validation

As we suggested earlier, the main problem with the Bigliani classification is that although its intraobserver reliability has varied–sometimes (though not always [4]) achieving kappa values in the good-to-excellent range [11, 25, 27]–its interobserver reliability has been consistently fair-to-poor [4, 9, 11, 23, 25, 27, 31]. This means that it is not suitable as a clinical communication tool among surgeons or clinician-scientists. In one study, in which six fellowship-trained shoulder surgeons reviewed 126 scapular outlet view radiographs (a scapular Y view with 10° of caudal tilt) of the shoulder observed good-to-excellent intraobserver reliability (κ = 0.888) and poor-to-fair interobserver reliability (κ = 0.516) [11]. Several further small studies observed that interobserver reliability was poor (κ = 0.25-0.41) [9, 25, 27, 31]. In another study, which again found only fair interobserver (κ = 0.35) reliability, both interobserver and intraobserver reliability were found not to vary according to surgeon experience level (from PGY-2 resident to fellowship-trained shoulder surgeon), or whether the observers were surgeons or radiologists [4]. Taken together, the interobserver reliability of the Bigliani classification of acromial morphology as reported by multiple studies is fair at best, regardless of level of expertise and training, and as such it should not be used to facilitate communication by orthopaedic surgeons, radiologists, or researchers.

The use of MRI to identify acromial morphology has also been studied. One small study compared a single oblique midsagittal MRI image in the plane of acromion and scapular outlet view radiographs of 32 shoulders in patients who had undergone impingement syndrome treatment [29]. Three shoulder surgeons independently reviewed MRI and radiographs. They graded acromial morphology almost identically when radiographs and MRI were compared, with 31 of 32 (97%) having the same acromial type. The authors concluded that MRI was as accurate as radiographs at determining acromial morphology [29]. A similar study compared the value of different MRI planes independently and in combination for assessment of acromial morphology compared with a scapular outlet view radiographs [14]. They found that scapular outlet view radiograph had fair agreement (κ = 0.55) but was superior to any single MRI image position that did not achieve higher than poor agreement (κ = -0.1 to 0.44). However, a combination of two MRI images showed good agreement (κ = 0.66)[14]. This conflicts with the previous study [29], which found that single MRI images were not different from scapular outlet view radiographs. This difference in agreement between the two studies may be due to the already well-documented poor-to-fair interobserver reliability, and as such, to an inability to use the Bigliani classification effectively for research purposes. Although more MRI images showed improved interobserver agreement, employing MRI to identify acromial morphology should be used with caution, if at all.

There is conflicting evidence regarding Bigliani’s original observation that rotator cuff tears were associated with Type III acromia [2, 3, 6–8, 10, 13, 17, 23, 24]. Many authors have found a correlation between Type III acromia and rotator cuff tears [2, 3, 6–8, 10, 13]. In one meta-analysis, patients with Type III acromia were more likely to present with rotator cuff tears [18]. By contrast, several other studies found that Bigliani Type III acromia were no more likely to have a rotator cuff tear than shoulders with a Type II or I acromia [17, 23, 24]. On balance, we consider the relationship between acromial morphology as defined by the Bigliani classification and rotator cuff pathology to be weak, if it is present at all. It is not possible to know whether this is because of a flawed anatomic premise (that a more-hooked acromion is more likely to damage the rotator cuff) or because of the considerable problems reported with the reliability of this classification system [4, 9, 11, 25].

Limitations

Different observers must be able to agree on the same classification when reviewing the same data (interobserver reliability) before a classification system should be used for clinical decision-making, communication between surgeons, prognosis, or research. Because the interobserver reliability of the Bigliani classification system [3] is only poor-to-fair (κ = 0.28-0.516 [4, 9, 11, 25]), it therefore should not be used for any of these purposes.

Some of its problems may derive from the system’s subjective descriptions. The original Bigliani classification does not give objective definitions of flat, curved, or hooked acromia, and thus it entirely depends upon each surgeon’s subjective interpretation. Two studies found that by using standardized criteria to define Type I, Type II, or Type III acromia, the interobserver reliability improved from poor (κ = 0.25 -0.28) to good-to-excellent (κ = 0.62- 0.77) [25, 27]. Whether their finding that standardization of this sort improves the system’s interobserver reliability must be verified by others. Some skepticism may be necessary in this regard, given how sensitive the system appears to be to the quality of the imaging. One study found that the interpretation of acromial morphology is influenced by the angle of the beam in the sagittal, coronal, and axial planes [26].

There is a dearth of research evaluating the effectiveness of the treatment of patients with rotator cuff pathology according to differences in acromial morphology. A single, small study observed that patients with Type III acromia were more likely to undergo surgery after undertaking nonoperative treatment of shoulder impingement than patients with either Types I or II acromia [30]. The utility of this study is limited because it was a small, single-surgeon case series using a questionable shoulder impingement diagnosis [30]. And until or unless surgeons and clinician-scientists find ways to improve the interobserver reliability of the Bigliani classification system, we believe it should not be used to estimate patients’ prognoses.

Conclusions

The Bigliani classification of acromial morphology is of some historical importance as the first system to classify acromial morphology. However, although it is widely used, we believe it should not be. Its interobserver reliability has generally been in the fair-to-poor range [4, 9], which means that two observers are unlikely to classify the same acromion similarly; consequently, this system simply has no place in clinical communication, determination of prognosis, or research (other than research to try to improve upon the ways we classify the acromion).

Attempts to improve reliability have been made using objective criteria to define the distinct types of acromial morphology and were somewhat successful [25, 27], but these findings must be reproduced by others before we should consider them convincing.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that neither he, nor any member of his immediate family, have funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his institution waived approval of the reporting of this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at Gold Coast University Hospital, Gold Coast, Australia.

References

- 1.Armstrong J. Excision of the acromion in treatment of the supraspinatus syndrome; report of 95 excisions. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1949;31:436–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balke M, Schmidt C, Dedy N, Banerjee M, Bouillon B, Liem D. Correlation of acromial morphology with impingement syndrome and rotator cuff tears. Acta Orthop. 2013;84:178–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LU Bigliani, Morrison DS, April EW. The morphology of the acromion and its relationship to rotator cuff tears. Ortho Trans. 1986;10:228. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bright AS, Torpey B, Magid D, Codd T, McFarland EG. Reliability of radiographic evaluation for acromial morphology. Skeletal Radiol. 1997;26:718–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Codman E, Akerson IB. The pathology associated with rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. Ann Surg. 1931;93:348–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein R, Schweitzer M, Frieman B, Fenlin JJ, Mitchell D. Hooked acromion: Prevalence on MR images of painful shoulders. Radiology. 1993;87:479–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farley TE, Neumann CH, Steinbach LS, Petersen SA. The coracoacromial arch: MR evaluation and correlation with rotator cuff pathology. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23:641–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill TJ, McIrvin E, Kocher MS, Homa K, Mair SD, Hawkins RJ. The relative importance of acromial morphology and age with respect to rotator cuff pathology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:327–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamid N, Omid R, Yamaguchi K, Steger-May K, Stobbs G, Keener JD. Relationship of radiographic acromial characteristics and rotator cuff disease: a prospective investigation of clinical, radiographic, and sonographic findings. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:1289–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirano M, Ide J, Takagi K. Acromial shapes and extension of rotator cuff tears: Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:576–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson SR, Speer KP, Moor JT, Janda DH, Saddemi SR, MacDonald PB, Mallon WJ. Reliability of radiographic assessment of acromial morphology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4:449–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitay GS, Iannotti JP, Williams GR, Haygood T, Kneeland BJ, Berlin J. Roentgenographic assessment of acromial morphologic condition in rotator cuff impingement syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacGillivray JD, Fealy S, Potter HG, O’Brien SJ. Multiplanar analysis of acromion morphology. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:836–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayerhoefer ME, Breitenseher MJ, Roposch A, Treitl C, Wurnig C. Comparison of MRI and conventional radiography for assessment of acromial shape. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:671–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minagawa H, Yamamoto N, Abe H, Fukuda M, Seki N, Kikuchi K, Kijima H, Itoi E. Prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears in the general population: From mass-screening in one village. J Orthop. 2013;10:8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moor BK, Bouaicha S, Rothenfluh DA, Sukthankar A, Gerber C, Bouaicha S. Is there an association between the individual anatomy of the scapula and the development of rotator cuff tears or osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint? A radiological study of the critical shoulder angle. Bone Joint J. 2013;95: 935-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moor BK, Wieser K, Slankamenac K, Gerber C, Bouaicha S. Relationship of individual scapular anatomy and degenerative rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:536–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morelli KM, Martin BR, Charakla FH, Durmisevic A, Warren GL. Acromion morphology and prevalence of rotator cuff tear: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Anat. 2019;32:122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrison D, Bigliani L. The clinical significance of variations in acromial morphology. Orthop Trans . 1987;11:234. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neer CS. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54A:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neer CS. Impingement Lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;173:70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyffeler RW, Werner CML, Sukthankar A, Schmid MR, Gerber C. Association of a large lateral extension of the acromion with rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:800–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandey V, Vijayan D, Tapashetti S, Agarwal L, Kamath A, Acharya K, Maddukuri S, Willems WJ. Does scapular morphology affect the integrity of the rotator cuff? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;5:413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panni AS, Milano G, Lucania L, Fabbriciani C, Logroscino CA. Histological analysis of the coracoacromial arch: Correlation between age-related changes and rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:531–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park T-S, Park D-W, Kim S-I, Kweon T-H. Roentgenographic assessment of acromial morphology using supraspinatus outlet radiographs. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2001;17:496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stehle J, Moore SM, Alaseirlis DA, Debski RE, McMahon PJ. Acromial morphology: Effects of suboptimal radiographs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;6:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stehle J, Moore SM, Alaseirlis DA, Debski RE, McMahon PJ. A reliable method for classifying acromial shape. Int Biomech. 2015;2:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanarthos WJ, JU Monu. Type 4 acromion: a new classification. Contemp Orthop. 1995;30:227–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang JC, Hatch JD, Shapiro MS. Comparison of MRI and radiographs in the evaluation of acromial morphology. Orthopedics. 2000;23:1269–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang JC, Horner G, Brown ED, Shapiro MS. The relationship between acromial morphology and conservative treatment of patients with impingement syndrome. Orthopedics. 2000;23:557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuckerman JD, Kummer FJ, Cuomo F GM. Interobserver reliability of acromial morphology classification: An anatomoic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 6:286–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]