Abstract

Background

Prolonged wound drainage after TKA is associated with increased risk of infection. To decrease wound drainage, tissue adhesive has been suggested as an adjunct to wound closure after TKA; however, no studies of which we are aware have investigated the effect of tissue adhesive in a modern fast-track TKA setting.

Questions/purposes

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of wound closure using a high-viscosity tissue adhesive in simultaneous bilateral TKA with respect to (1) postoperative wound drainage, measured as number of dressing changes in the first 72 hours postoperatively; and (2) wound healing assessed using the ASEPSIS score.

Methods

Thirty patients undergoing simultaneous bilateral TKA were included in the study. The left knee was randomized to receive either standard three-layer closure with staples or the same closure supplemented with tissue adhesive with the opposite treatment used on the contralateral knee. One patient underwent a constrained TKA and underwent revision 2 days after the index procedure and was therefore excluded leaving 29 patients (58 knees) for analysis. Sixty-two percent (n = 18) were female. Mean age was 64 years (range, 42-78 years). Mean body mass index was 28 kg/m2 (range, 21–38 kg/m2). Postoperative wound drainage was evaluated as drainage resulting in a dressing change. The wound dressing was changed if it was soaked to the borders of the absorbable dressing at any point. The nurses changing the dressing were blinded to treatment allocation up to the first dressing change. The number of dressing changes during the first 72 hours postoperatively was recorded. The secondary study endpoint was the ASEPSIS score, which is a clinical score assessing wound healing. ASEPSIS score, measured by a nurse not involved in the treatment, was compared between the groups at 3 weeks followup.

Results

Knees with tissue adhesive underwent fewer dressing changes (median, 0; interquartile range [IQR], 0-1) compared with the contralateral knee (IQR, 1-2; difference of medians, one dressing change; p = 0.001). A total of 59% of knees in the intervention group did not undergo any dressing changes before discharge, whereas 24% of knees in the control group did not undergo any dressing changes before discharge (p = 0.02). The knees in the intervention group and the control group did not differ with respect to ASEPSIS score at 3 weeks.

Conclusions

Tissue adhesive as an adjunct to standard wound closure after primary TKA reduced the number of dressing changes after surgery, but did not change the appearance or healing of the wound at 3 weeks based on the ASEPSIS scores. Whether the small differences observed here in terms of the number of dressing changes performed will justify the additional costs associated with using this product or whether there are other differences associated with the use of tissue adhesive that may prove important such as patient preferences or longer term differences in wound healing or infection should be studied in the future.

Level of Evidence

Level I, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Prolonged wound drainage after total joint arthroplasty has been shown to be a predictor of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) [21–23] with up to 28% of the patients with persistent wound drainage (48 hours) undergoing further surgery [12]. Although the correct time to débride a draining wound is debated, the recent Proceedings of the International Consensus on Periprosthetic Joint Infection recommended revising a surgical wound that had been persistently draining for > 5 to 7 days [19]. Wound drainage may be associated with prosthetic joint infections [21–23], which represent a challenging complication potentially leading to poorer outcome scores and an increased risk of death [18, 27].

In light of the concern that prolonged drainage may lead to PJI [21–23], it seems sensible that steps that could decrease drainage may reduce the risk of infection, and so such steps might be worth exploring. In recent years, tissue adhesives for wound closure have been introduced as a replacement or a supplement to conventional closure techniques. However, few studies have investigated the effect of tissue adhesive on wound drainage after TKA and no studies to our knowledge have investigated the effect of tissue adhesive in a modern fast-track TKA protocol with early mobilization without use of drains or a tourniquet and with short thromboembolic chemoprophylaxis, all factors that potentially affect wound drainage [7, 14].

Therefore, the aim of this prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) was to evaluate the effect of supplemental wound closure using a high-viscosity tissue adhesive (Leukosan®; BSN Medical, Hamburg, Germany) in simultaneous bilateral primary TKA with respect to (1) postoperative wound drainage, measured as number of dressing changes in the first 72 hours postoperatively; and (2) wound healing assessed using the ASEPSIS score.

Patients and Methods

This randomized study was conducted in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Ethics Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark; # H-15009317) and registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03289247).

Patients scheduled for bilateral simultaneous TKA by the senior author (HH) were screened for participation. Inclusion criteria were patients > 18 years old who were suitable for primary simultaneous bilateral TKA based on physical examination and medical history with clinically and radiographically verified osteoarthritis [9]. Patients receiving potent anticoagulants before surgery (such as new oral anticoagulants or vitamin K antagonists), with previous open knee surgery on either knee, with previous major trauma to either knee resulting in deformity or scarring or with allergies to skin adhesives were excluded.

Sample size analysis was based on the primary outcome, which was the number of dressing changes during the first 72 hours after surgery. The minimum difference we considered important, based on consensus from all coauthors of this article, was a 50% decrease from previous experience showing an average of three dressing changes. Based on this, we calculated 24 knees should be included in each group in light of a sample size calculation that set power at 0.9 and α = 0.05. Thus, 30 patients were included in the study, allowing for 25% dropout.

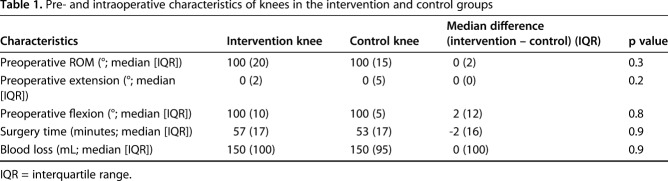

A total of 30 patients were included in the study. One patient received increased constraint of the TKA and underwent revision 2 days postoperatively and was therefore excluded leaving 29 patients (58 knees) for analysis (Fig. 1). Sixty-two percent (n = 18) were women. Mean age was 64 years (range, 42-78 years). Mean body mass index (BMI) was 28 kg/m2 (range, 21–38 kg/m2). Intervention and control knees did not differ regarding preoperative ROM, intraoperative blood loss, or surgery time (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Thirty-two patients were screened for eligibility, 30 patients were included and randomized, and 29 patients were included in the final analysis.

Table 1.

Pre- and intraoperative characteristics of knees in the intervention and control groups

The study followed the CONSORT statement (Fig. 1). Opaque envelopes were used for the computer-generated randomization process, and envelopes were opened intraoperatively before skin closure of the first knee, which always was the left side. The left knee was thus randomized to receive either (1) a standard three-layer closure method with skin staples; or (2) a three-layer closure method with skin staples supplemented with tissue adhesive (Leukosan) with the opposite treatment on the contralateral knee. All patients were operated on between January 11, 2015, and January 9, 2017, in a well-described fast-track setup [10] with a cruciate-retaining TKA (AGC® or Persona® ; Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA).

The surgical technique a standard midline skin incision with a medial parapatellar capsulotomy was used. Femur and tibial surfaces were prepared using standard cutting guides. The ACL was resected and the posterior cruciate ligament retained. Ligament balancing was achieved using a measured resection technique. Femoral and tibial components were cemented. Resurfacing of the patella was performed in all knees.

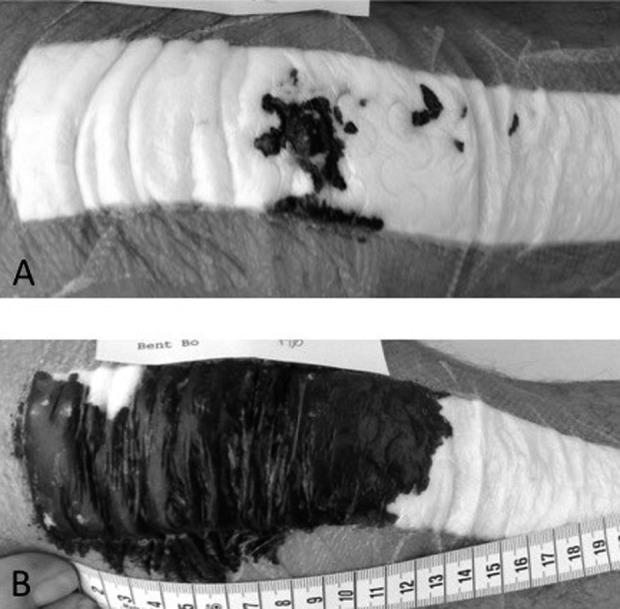

The joint capsule was closed using size 2 coated VICRYL® Plus antibacterial suture (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA), whereas subcutaneous tissue was closed using size 2-0 coated VICRYL Plus antibacterial suture (Ethicon). The skin was closed with stainless steel staples using a PROXIMATE® Fixed-Head stapler (Ethicon) intended to be placed 5 mm apart. If the knee was randomized to the intervention group, tissue adhesive (Leukosan) was applied on top of the staples according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One layer (one tube) of tissue adhesive was applied after air-drying for 60 seconds followed by placement of a second layer (one tube) and a second air-drying period of 60 seconds. No drains or tourniquets were used. A standard Mepilex Border Post-op® wound dressing (Mölnlycke, Gothenburg, Sweden) was applied to the wound followed by an Acryelastic® compression bandage (BSN Medical, Vibraye, France) [1]. All patients were allowed immediate postoperative mobilization without restrictions. The compression bandage was removed on the first postoperative day. The wound dressing was changed if it was soaked to the borders of the absorbable dressing at any point (Fig. 2). On discharge, the patients were instructed to change the bandage if it was soaked through. If the bandage was dry, the patients could remove it after 7 days. All bandages were continuously assessed by the same nurse (SR) during the day. If the bandage called for a change according to study parameters outside her working hours, the shift nurse was instructed in the criteria by the author (SR) and was asked to photo-document the bandage. Postoperatively, participants received standard pain treatment and rehabilitation until discharge [11]. Patients received oral thromboembolic prophylaxis given as 10-mg rivaroxaban tablets once daily until discharge starting 6 to 8 hours postoperatively. No extended thromboembolic prophylaxis was given to any patients. All patient received 1 g intravenous (IV) tranexamic acid (TXA) preoperatively and 1 g IV TXA 3 hours postoperatively. All patients were admitted for a minimum of 72 hours, during which the number of dressing changes for each knee was registered. Nurses changing the dressing were blinded to treatment allocation up to the first dressing change; no blinding was possible after the first bandage change.

Fig. 2 A-B.

Image of a wound presentation the day after surgery on the same patient. (A) This wound did not require a dressing change, whereas (B) this wound required a dressing change.

The primary outcome was the number of dressing changes during the first 72 hours postoperatively. The secondary outcome was the objective wound assessment part of the ASEPSIS score [25] at 3 weeks and ROM at 3 weeks, both recorded by the nurses at the outpatient clinic who were not involved in patient treatment. The ROM was measured by the surgeon preoperatively and by the nurses postoperatively using a goniometer. The ASEPSIS score is a commonly used wound assessment score [26], which has been proposed to be suitable for orthopaedic infection surveillance [2]. The ASEPSIS score consists of an objective wound assessment part, a part about wound treatment, and a part regarding consequences of the infection (Table; Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A132). Patient demographics were recorded as well as preoperative ROM and adverse events 3 months after surgery. Surgical parameters such as surgery time (first incision to and including placement of the dressing) as well as intraoperative blood loss were recorded. Intraoperative blood loss consisted of suction production as well as additional weight of fluid in the surgical sponges.

All outcome measures were numeric, skewed, and nonnormal distributed. We computed median and interquartile range. Comparison of the two groups was performed using the Mann-Whitney test. For outcome measures with a great number of ties, normal approximation of the Mann-Whitney test was applied. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R 3.2.3 (www.r-project.com).

Results

Knees in the intervention group had fewer dressing changes within 72 hours (median, 0; interquartile range [IQR], 1 versus median, 1; IQR, 1; p = 0.001). A smaller proportion of patients in the tissue adhesive group received dressing changes than did those in the control group (45% [13 of 29] versus 72% [21 of 29]; odds ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.9; p = 0.020). No knees had wound drainage > 7 days. No allergic reactions to the tissue adhesive [6] were reported.

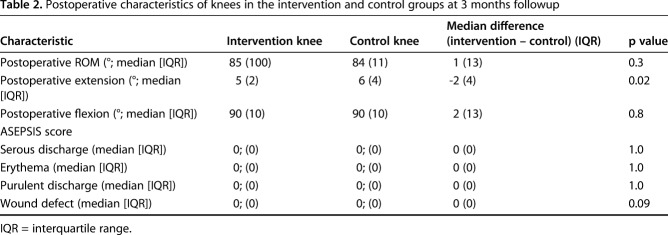

The knees in the intervention group and the control group did not differ with respect to ASEPSIS scores at 3 weeks (Table 2). In addition, there were no clinically important differences in ROM between the study groups 3 months after surgery (Table 2). One knee in the control group underwent irrigation and débridement at 4 weeks as a result of infection.

Table 2.

Postoperative characteristics of knees in the intervention and control groups at 3 months followup

Discussion

Prolonged wound drainage after total joint arthroplasty has been shown to be a predictor of PJI. Therefore, tissue adhesive has been suggested as a supplement to wound closure after primary TKA to reduce wound drainage. However, no studies have investigated the effect of tissue adhesive in a modern fast-track TKA protocol.

In this randomized trial of patients undergoing simultaneous bilateral TKA, we found that use of high-viscosity tissue adhesive (Leukosan) as a supplement to wound closure resulted in patients undergoing fewer dressing changes in the first 72 hours after surgery. However, wound appearance as defined by ASEPSIS scores did not differ between intervention and control knees at 3 weeks followup.

The main limitation of our study is the clinical relevance of our primary outcome. Wound drainage could also be measured as volume as described by El-Gazzar et al. [7] or by weighing the bandage each day. However, this would call for removing a bandage that might not need to be changed, thus needlessly uncovering the surgical incision. Also, measuring weight or volume would be associated with substantial and potentially misleading inaccuracies when comparing wounds that leaked outside the bandage with wounds with less drainage. Thus, we believe that measuring weight or volume with respect to wound drainage would be associated with just as many, if not more, limitations as our current method. Although we tried to make the indications for bandage change as objective as possible, the evaluation of whether the bandage is soaked to the edge is associated with some subjectivity. Because our study investigates dressing changes, it is not possible to draw any direct conclusions on the clinical effect of tissue adhesive on wound healing and infections, and the study was neither powered nor designed to do so. The most clinically relevant outcome for such study would be infection. However, performing a RCT with infection as the primary outcome is virtually impossible because several thousand patients would need to be included to provide an adequate sample size and power, especially in a simultaneous bilateral setup. Another limitation is that we only measured wound drainage during the first 72 hours after surgery. The reason for this is that the majority of patients undergoing simultaneous bilateral TKA fulfill discharge criteria within 3 days [9], and keeping patients in the hospital for observation only was not considered ethical. Although patient-reported wound drainage could have been an option, we believe that this method is somewhat inaccurate, and we therefore chose to focus on clinical evaluation on wound discharge within 3 days after surgery. External validity is also a limitation, because both wound closure protocols and perioperative treatment affecting wound discharge differ between departments and might affect findings presented in this study. Thromboembolic prophylaxis is one such factor, because thromboembolic prophylaxis has been shown to increase wound discharge [13] and only short-duration thromboembolic prophylaxis during the hospital stay is used in our department, which might not be the case at other institutions. The ASEPSIS score, which we used as a secondary outcome, has been validated in several surgical procedures, but to our knowledge not in arthroplasty [3, 24]. We only used the clinical part of the ASEPSIS score, because we only wanted to evaluate the clinical appearance of the wound. Also, information regarding débridement, antibiotics, and isolation of bacteria might be misleading early after surgery (3 weeks followup). We have not investigated the financial implications of using tissue adhesive tubes to reduce the number of bandage changes because the cost of both tissue adhesive and bandages can vary greatly among departments, making comparisons difficult. Finally, blinding could not be maintained after the first bandage change, perhaps introducing bias when assessing outcome [4] after the first bandage change.

The use of simultaneous bilateral TKA for this RCT can be considered a strength as well as a weakness. The patient serves as his or her own control, thus eliminating all patient-related confounding such as BMI, coagulopathy, and individual wound-healing abilities. On the other hand, patients undergoing simultaneous bilateral TKA ambulate slower compared with patients undergoing unilateral TKA, which might affect wound healing and wound discharge immediately after surgery. In addition, patients undergoing simultaneous bilateral TKA generally are healthier and have fewer comorbidities compared with patients undergoing unilateral TKA, which might affect wound healing, thus making our results less generalizable to a general TKA population. We therefore believe that a large followup study on unilateral TKA is warranted to further establish the role of tissue adhesive as a supplement for wound closure after primary TKA, but with a focus on wound healing problems within 3 months.

We found that tissue adhesive as a supplement to wound closure reduced the number of dressing changes in the first 72 hours after surgery. These findings are in accordance with another RCT investigating the effect of tissue adhesive on postoperative wound drainage after TKA [7]. El-Gazzar et al. [7] found that supplemental use of tissue adhesive for wound closure after primary TKA reduced postoperative wound drainage. However, the results of the two studies are not directly comparable, because wound discharge in the study by El-Gazzar et al. [7] was calculated using estimated discharge volume in the dressings on Days 2 and 3, whereas we investigated the number of dressing changes. Although the best method for evaluating wound drainage can be debated, we believe that the duration of drainage, rather than volume, is more clinically relevant, because prolonged wound drainage has been correlated to infection and revision after TKA [20–22]. To our knowledge, only two other studies (one RCT on primary TKA and one RCT on both TKA and THA) have investigated the effect of tissue adhesive in primary TKA [7, 15], whereas tissue adhesive is widely used in other types of surgical procedures [5, 16, 17]. It is important to emphasize that this study investigates use of tissue adhesive as an adjunct to wound closure and not as a substitute for staples or sutures. Studies have shown that sutures minimize dehiscence compared with tissue adhesive and tissue adhesive alone might not be sufficient in wounds with high tension such as TKA [5]. This is highlighted by the findings by Khan et al., who reported increased wound drainage after TKA and THA after 24 hours when only tissue adhesive was used for skin closure [15].

We did not find any difference with respect to clinical wound appearance at 3 weeks as measured by the clinical component of the ASEPSIS score. This most likely was the result of the low number of patients in our study, making ASEPSIS score an imperfect measure for this purpose, which is illustrated by a median score of 0 in both groups. Because few patients, even in high-risk groups, experience wound complications [8], a rather high number of patients would be required to detect a difference in wound healing between the two groups.

In conclusion, we found tissue adhesive as an adjunct to standard wound closure after primary TKA reduced the number of dressing changes after surgery. Future studies should investigate the effect of tissue adhesive on wound healing and PJI.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that neither he or she, nor any member of his or her immediate family, has funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, Copenhagen, Denmark.

References

- 1.Andersen LØ, Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H. A compression bandage improves local infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop . 2008;79:806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashby E, Haddad FS, O’Donnell E, Wilson AP. How will surgical site infection be measured to ensure 'high quality care for all'? J Bone Joint Surg Br . 2010;92:1294–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne DJ, Napier A, Cuschieri A. Validation of the ASEPSIS method of wound scoring in patients undergoing general surgical operations. J R Coll Surg Edinb . 1988;33:154–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gotzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, Dickersin K, Hrobjartsson A, Schulz KF, Parulekar WR, Krleza-Jeric K, Laupacis A, Moher D. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumville JC, Coulthard P, Worthington H V, Riley P, Patel N, Darcey J, Esposito M, van der Elst M, van Waes OJF. Tissue adhesives for closure of surgical incisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2014;11:CD004287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durando D, Porubsky C, Winter S, Kalymon J, O’Keefe T, LaFond AA. Allergic contact dermatitis to Dermabond (2-octyl cyanoacrylate) after total knee arthroplasty. Dermatitis. 2014;25:99–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Gazzar Y, Smith DC, Kim SJ, Hirsh DM, Blum Y, Cobelli M, Cohen HW. The use of Dermabond® as an adjunct to wound closure after total knee arthroplasty: examining immediate post-operative wound drainage. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George J, Piuzzi NS, Ng M, Sodhi N, Khlopas AA, Mont MA. Association between body mass index and thirty-day complications after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:865–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gromov K, Troelsen A, Stahl Otte K, Ørsnes T, Husted H. Morbidity and mortality after bilateral simultaneous total knee arthroplasty in a fast-track setting. Acta Orthop . 2016;87:286–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop Suppl . 2012;83:1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husted H, Solgaard S, Hansen TB, Søballe K, Kehlet H. Care principles at four fast-track arthroplasty departments in Denmark. Dan Med Bull . 2010;57:A4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaberi FM, Parvizi J, Haytmanek CT, Joshi A, Purtill J. Procrastination of wound drainage and malnutrition affect the outcome of joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2008;466:1368–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones CW, Spasojevic S, Goh G, Joseph Z, Wood DJ, Yates PJ. Wound discharge after pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in lower limb arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan F, Ng L, Gonzalez S, Hale T, Turner-Stokes L. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes following joint replacement at the hip and knee in chronic arthropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2008;2:CD004957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan RJK, Fick D, Yao F, Tang K, Hurworth M, Nivbrant B, Wood D. A comparison of three methods of wound closure following arthroplasty: a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br . 2006;88:238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khurana A, Parker S, Goel V, Alderman PM. Dermabond wound closure in primary hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Belg . 2008;74:349–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livesey C, Wylde V, Descamps S, Estela CM, Bannister GC, Learmonth ID, Blom AW. Skin closure after total hip replacement: a randomised controlled trial of skin adhesive versus surgical staples. J Bone Joint Surg Br . 2009;91:725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakano N, Matsumoto T, Ishida K, Tsumura N, Muratsu H, Hiranaka T, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M. Factors influencing the outcome of deep infection following total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2015;22:328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parvizi J, Gehrke T, Chen AF. Proceedings of the International Consensus on Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Bone Joint J . 2013;95:1450–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel VP, Walsh M, Sehgal B, Preston C, DeWal H, Di Cesare PE. Factors associated with prolonged wound drainage after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peel TN, Dowsey MM, Daffy JR, Stanley PA, Choong PF, Buising KL. Risk factors for prosthetic hip and knee infections according to arthroplasty site. J Hosp Infect . 2011;79:129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saleh K, Olson M, Resig S, Bershadsky B, Kuskowski M, Gioe T, Robinson H, Schmidt R, McElfresh E. Predictors of wound infection in hip and knee joint replacement: results from a 20 year surveillance program. J Orthop Res . 2002;20:506–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scuderi GR. Avoiding postoperative wound complications in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018. Feb 21. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siah CJ, Childs C. A systematic review of the ASEPSIS scoring system used in non-cardiac-related surgery. J Wound Care. 2012;21:124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson AP, Treasure T, Sturridge MF, Grüneberg RN. A scoring method (ASEPSIS) for postoperative wound infections for use in clinical trials of antibiotic prophylaxis. Lancet. 1986;1:311–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson APR, Gibbons C, Reeves BC, Hodgson B, Liu M, Plummer D, Krukowski ZH, Bruce J, Wilson J, Pearson A. Surgical wound infection as a performance indicator: agreement of common definitions of wound infection in 4773 patients. BMJ. 2004;329:720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zmistowski B, Karam JA, Durinka JB, Casper DS, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection increases the risk of one-year mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2013;95:2177–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]