Abstract

Hope is a trait that represents the capacity to identify strategies or pathways to achieve goals and the motivation or agency to effectively pursue those pathways. Hope has been demonstrated to be a robust source of resilience to anxiety and stress and there is limited evidence that, as has been suggested for decades, hope may function as a core process or transdiagnostic mechanism of change in psychotherapy. The current study examined the role of hope in predicting recovery in a clinical trial in which 223 individuals with 1 of 4 anxiety disorders were randomized to transdiagnostic cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), disorder-specific CBT, or a waitlist controlled condition. Effect size results indicated moderate to large intraindividual increases in hope, that changes in hope were consistent across the five CBT treatment protocols, that changes in hope were significantly greater in CBT relative to waitlist, and that changes in hope began early in treatment. Results of growth curve analyses indicated that CBT was a robust predictor of trajectories of change in hope compared to waitlist, and that changes in hope predicted changes in both self-reported and clinician-rated anxiety. Finally, a statistically significant indirect effect was found indicating that the effects of treatment on changes in anxiety were mediated by treatment effects on hope. Together, these results suggest that hope may be a promising transdiagnostic mechanism of change that is relevant across anxiety disorders and treatment protocols.

Keywords: Hope, CBT, Anxiety, Mechanism of Change, Transdiagnostic

Remarkable progress has been made in developing evidence-based treatments for anxiety disorders in recent decades (Barlow, 2014). Cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) protocols now exist for each of the anxiety disorders that have been shown to be generally efficacious in promoting symptom recovery. One of the noteworthy aspects of this progress is the evidence from psychotherapy research and clinical trials that different forms of CBT often have very similar outcomes when compared directly (e.g., Resick et al., 2002). Although considerable debate remains about the relative role of common factors versus treatment specific mechanisms, there is a clear need to improve our understanding of the causal factors or mechanisms of change of empirically-supported treatments (Kazdin, 2007), and to consider whether shifting our focus to the core competencies and transdiagnostic processes of CBT may be a more effective long-term strategy for improving CBT treatments (Hayes & Hofmann, 2018). The present study focuses on the role of hope as a potential core component or transdiagnostic mechanism of change in CBT treatments for anxiety disorders.

Defining Hope

The most widely studied model of hope presupposes that human behavior is motivated by the identification and pursuit of goals, and defines hope as the interaction of pathways thinking, or the capacity to identify strategies to pursue one’s goals, and agency thinking, or the motivation to effectively pursue one’s pathways to achieve goals (Snyder, 2002). These components are complementary and bidirectional, alternately boosting motivation and promoting goal-directed behavior. For example, having hope in one’s ability to solve problems helps one persevere when confronted with obstacles and stressful situations (Snyder, 2002). Snyder’s model frames hope as a cognitive process, emphasizing the role of positive expectations while pursuing goals.

Hope is closely related to other positive psychology constructs such as self-efficacy and optimism that have also been shown to have clear relevance to promoting resilience to and recovery from emotional disorders. There are important conceptual and empirical differences between these constructs, however, that provide clear evidence that hope may uniquely influence anxiety disorders and related outcomes. Bandura (1997) defines self-efficacy as the perceived ability to perform the necessary behaviors to achieve a desired outcome. However, Bandura’s theory does not concern the ability to generate pathways towards one’s goals, and places less emphasis on one’s motivation to enact the behaviors required to achieve them (Rand, 2018). Optimism, on the other hand, is a general positive expectancy that good things will happen in the future (Scheier & Carver, 1985). While optimism is also a type of positive expectancy, it does not focus on the individual’s perceived intention or capacity to bring about the future good. Studies using confirmatory factor analysis have demonstrated that although hope, optimism, and self-efficacy are moderately to highly correlated, they are distinct constructs (Magaletta & Oliver, 1999). Therefore, while there is evidence of self-efficacy as potential mechanism of change of CBT for anxiety disorders (e.g., Gallagher et al., 2013), it is important to demonstrate the specific role that hope may have in promoting recovery during CBT.

Hope is also relevant to widely examined cognitive constructs in the anxiety disorders realm that are related to vulnerability to or recovery from emotional disorders. For example, perceived control in relation to negative emotions and negative events has been proposed to be a transdiagnostic vulnerability factor that plays an important role in the development of the anxiety disorders (Barlow, 2002). Meta-analytic reviews have supported this theory and have shown that deficits in perceived control are a robust predictor of higher symptoms of multiple anxiety disorders (Gallagher, Bentley, & Barlow, 2014) and changes in perceived control following CBT treatment predict the longitudinal course of anxiety symptoms across diagnostic boundaries (Gallagher, Naragon-Gainey, & Brown, 2014). There is limited empirical evidence regarding the link between hope and perceived control, but conceptually perceived control differs from hope in that perceived control focuses on domain specific evaluations of the potential capacity to control negative emotions/experiences rather than global evaluations of one’s capacity and likelihood to do what is necessary to achieve one’s goals, and perceived control does not capture the strategies or pathways by which coping may occur, as does hope.

Treatment outcome expectancy is another cognitive process that is conceptually relevant to hope and has been widely examined in relation to treatment outcome for anxiety disorders. Many studies have examined expectancy beliefs during CBT for anxiety disorders and found expectancy to be an important predictor of both treatment process and outcomes (e.g., Constantino, Visla, Coyne & Boswell, 2018). Commonly measured using the credibility and expectancy questionnaire (CEQ; Devilly & Borkovec, 2000), expectancy captures more global positive expectancies regarding treatment and is assessed using items such as “How much do you really feel that therapy will help you to reduce your symptoms”. Expectancy as traditionally examined in CBT trials is therefore more similar conceptually to optimism than hope as it focuses on generalized positive expectancies rather pathways cognitions or personal agency. There is some evidence from other contexts that hope and expectancy beliefs have a weak, positive correlation (Haanstra, Tilbury, Kamper, Tordoir Vliet Vlieland et al., 2015), but outcome expectancy beliefs have been more widely examined in past work than the more general construct of hope (Halperin, Weitzman, & Otto, 2010). Thus, while hope is linked to cognitive constructs that are commonly examined in the CBT treatment outcome literature, hope is conceptually and empirically distinct from these constructs.

Hope and Mental Health

Decades of research have now demonstrated that hope is broadly relevant to positive mental health and many forms of psychopathology (Gallagher & Lopez, 2018; Ritschel & Sheppard, 2018; Snyder, 2002). Those high in hope tend to experience positive emotions during goal pursuit and are more motivated to persist in the face of obstacles (Snyder, 2002). Hope is a robust predictor of various facets of positive mental health even when controlling for related constructs such as optimism (Gallagher & Lopez, 2009). Higher levels of hope are also a robust predictor of negative affect and psychopathology, with meta-analytic reviews demonstrating the robust associations across many studies (Alarcon, Bowling, & Khazon, 2013). In particular, hope appears to be associated with lower levels of anxiety and stress disorders (Long & Gallagher, 2018; Arnau, 2018), and there is evidence that hope prospectively predicts lower levels of anxiety even when controlling for previous levels of anxiety (Arnau et al., 2007).

There is also increasing evidence regarding the mechanisms by which hope may promote higher levels of mental health and lower levels of anxiety and related disorders, and why, therefore, promoting hope during treatment may, in turn, promote recovery during CBT for anxiety disorders. Individuals high in hope tend to perceive obstacles as less stressful, are quicker to rebound from obstacles, and demonstrate resilience in response to challenging circumstances (Snyder, 2002). Hope is associated with adaptive coping styles such as problem-focused coping and active coping, and is inversely related to maladaptive coping styles such as denial and distancing (e.g., Hassija, Luterek, Naragon-Gainey, Moore, & Simpson, 2012). Therefore, one way hope may contribute to recovery during CBT is by serving as a positive trait that provides a foundation for facilitating effective coping, regardless of the specific diagnosis being treated.

Hope in Psychotherapy

Beyond the recent evidence regarding the mental health benefits of hope, there is a long tradition of suggesting hope as a psychological resource that may be broadly relevant in psychotherapy (Frank, 1968; Frank & Frank; 1993). It is proposed that a consistent element of all effective psychosocial treatments may be the reestablishment and promotion of hope, and although hope should not be considered the sole factor in promoting recovery during psychotherapy, the instillation of hope in psychotherapy may be a mechanism that facilitates recovery across diagnoses and across different psychotherapy modalities, including those that do not explicitly target hope (Snyder et al., 2000; Snyder, Ilardi, Michael, & Cheavens 2000). As a core process or mechanism of treatment, hope can engender motivation, promote healthy coping, and aid in pursuit of goals in the context of psychotherapy (Snyder, Ilardi, Cheavens, Michael, Yamhure, & Sympson, 2000).

Although evidence suggests that hope is a generally stable trait (Marques & Gallagher, 2017), there is increasing evidence that hope is malleable and that targeted brief interventions can lead to increases in hope (Feldman & Dreher, 2012) and that psychotherapy can also result in meaningful increases in hope. Interventions developed to specifically target hope have been shown to lead to significant increases in hope as well as improvements in depression, anxiety and meaning in life (Cheavens, Feldman, Gum, Michael & Snyder, 2006). There is also evidence that interventions for stress and anxiety disorders that do not specifically target hope can produce substantial intraindividual changes in hope (Gilman et al., 2012) and that hope is an important predictor both at the early stages of treatment as well as functioning during later stages of psychotherapy (Irving et al., 2004).

Hope in CBT

Hope may be especially relevant within CBT, because it is problem-focused and involves forming specific goals and strategies (i.e., pathways) to more effectively cope with symptoms of anxiety and depression, and motivating clients to pursue them (agency; Beck, 2011). Prior to entering therapy, clients may be relatively demoralized and lacking in motivation because they have not been able to address their problems with their current coping skills (Frank & Frank, 1991; Snyder et al., 2000; Cheavens, Feldman, Woodward & Snyder, 2006). However, clients begin to demonstrate agency by initiating treatment, which represents a viable pathway towards ameliorating their symptoms. When presented with a convincing treatment rationale, client’s hopeful thinking will then be reinforced. During this remoralization stage of therapy, they will develop positive expectations about the course and outcomes of treatment as well as the agency to make changes in their lives (Irving et al., 2004).

In order to address the client presenting problems, CBT involves setting relevant and attainable goals, which maximally engender hope (Snyder et al., 2000). CBT therapists help clients generate pathways towards their goals and break them down into manageable steps. Within the context of emotional disorders, for example, treatment via exposure can be thought of as a CBT-specific pathway towards the goal of symptom reduction (Snyder, et al., 2000; Cheavens et al., 2006). The process of habituation and building tolerance of engaging with feared situations or stimuli while progressing through the exposure hierarchy sustains agency and pathways thinking, which should generalize outside of treatment. During the termination phase of therapy, reviewing treatment gains of therapy reinforces agency, and considering ways to address future obstacles, a common component of relapse prevention, builds pathways thinking (Cheavens et al., 2006). The skills that clients build to cope with strong emotions within the context of CBT should generalize to other areas of their lives after termination, thereby preventing relapse (Snyder et al., 2000).

Evidence of Hope as a Mechanism of Recovery During CBT

If hope operates as a consistent mechanism of recovery, the benefits of bolstering hope should be broadly applicable across CBTs for different emotional disorders and forms of psychopathology (Gallagher, 2017). Preliminary evidence provides some support for the role of hope as a mechanism of change within the context of CBT. Within the context of Cognitive Processing Therapy, considered one of the “gold standard” CBT treatments for PTSD, levels of hope at midtreatment were associated with decreases in PTSD symptoms (Gilman et al., 2012). In addition, people who experienced sudden gains during treatment tended to have had greater hope-related cognitions during the preceding session within the context of exposure-based cognitive therapy for depression (Hayes et al., 2007). A study by Irving et al. (2004) found that higher baseline hope after completing a 5-week pre-therapy orientation group (designed to identify goals and bolster pathways and agency) was associated with improvements in symptoms and functioning throughout the course of subsequent treatment for clients with primary emotional disorder diagnoses. Furthermore, increases in agency were associated with improved functioning midway through therapy, while increased pathways were associated with greater subjective well-being prior to termination. Evidence to date, therefore, suggests that CBT does, in fact, promote hope (and decrease the related construct of hopelessness; e.g., Gallagher & Resick, 2012) and that these changes are associated with symptom improvement.

Unresolved Questions

Despite the compelling theoretical case for the potential role of hope as a transdiagnostic mechanism or core process in CBT and the promising evidence reviewed, there are important limitations in the current evidence regarding the role of hope as a mechanism of CBT. Specifically, there is limited data directly comparing the impact of treatment protocols on hope. If hope is truly a core element of CBT, then the effect size magnitude of increases in hope during different treatments and in the treatment of different diagnoses should be generally consistent. There is also limited evidence regarding the timing of when changes in hope occur during treatment. The demonstration of temporal precedence of change is a crucial factor in identifying mechanisms of change (Kazdin, 2007), but we have limited evidence that hope changes early in treatment, which would be one step in concluding that hope may be a causal mechanism of recovery during treatment. Finally, there is limited evidence regarding how trajectories of hope during treatment predict symptom trajectories, which limits our understanding of the degree to which changes in hope relate to recovery during treatment. Demonstrating that different forms of CBT consistently promote hope and that hope consistently predicts symptom recovery would support the decades-long contention that instilling hope may be an important core process of efficacious treatments for anxiety disorders.

Study Aims

The goals of the present study were to 1) quantify the magnitude and timing of the impact of CBT on hope, 2) examine the extent to which changes in hope during CBT were consistent across principal diagnosis and treatment protocol, and 3) examine the extent to which intraindividual changes in hope predicted changes in self-reported and clinician-rated anxiety outcomes. Our hypotheses were that CBT would result in moderate to large increases in hope, that the increases in hope would be consistent across treatments and protocols, and that changes in hope would not only predict changes in anxiety, but would also partially temporally precede changes in anxiety. These hypotheses were examined using data from a recently published clinical trial that compared active CBT protocols and a wait list condition (Barlow, Farchione, Bullis, Gallagher, Murray-Latin et al., 2017).

Method

Participants

Participants were 223 adults (55.6% female) who sought treatment at a large outpatient clinic in Boston, MA. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 66 years with a mean of 31.1 (SD = 11.0). The majority of participants identified as Caucasian (83.4%), not currently married (78.9%), and with a college degree or higher (66.8%). In order to be eligible for the trial, participants had to receive a principal diagnosis of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (PDA; 26.5%), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; 27.8%), social anxiety disorder (SOC; 26.0%), or obsessive-compulsive disorder (19.7%). A large majority (84.3%) of participants met criteria for at least 1 comorbid diagnosis, with an average of 2.3 (SD = 1.8) comorbid diagnoses.

Experimental Design and Conditions

See Barlow et al. (2017) for more complete details about the study design and conditions. Participants were randomized based on their principal diagnosis to receive transdiagnostic CBT, disorder specific CBT, or a waitlist controlled condition using block randomization and a 2:2:1 allocation ratio. Transdiagnostic CBT consisted of the Unified Protocol (Barlow et al., 2017), a recently developed modular CBT protocol that was designed to be used across anxiety and mood disorders. Disorder specific CBT protocols were selected as gold-standard treatments, such that each had demonstrated efficacy for the respective diagnosis and included: Managing Social Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach, (MSA; Hope, Heimberg & Turk, 2010), Mastery of Your Anxiety and Worry, second edition (MAW; Craske and Barlow, 2006), Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic, fourth edition (MAP; Barlow and Craske, 2006), and Treating Your Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder With Exposure and Response (Ritual) Prevention Therapy, second edition (MOCD; Foa, Yadin, and Lichner, 2012). In all conditions, outcomes were assessed at baseline, session 4, session 8, session 12, and session 16. Participants with a principal diagnosis of panic disorder received a 12 week course of treatment as specified in the MAP protocol, but completed an additional assessment four weeks post-treatment to provide outcome data at the same time as session 16 for participants in other conditions and to facilitate comparisons across diagnoses/treatments. A six month follow-up assessment was completed by participants in the active treatment conditions.

Measures

Hope.

The State Hope Scale (SHS; Snyder, Sympson, Ybasco, Borders, Babyak, & Higgins, 1996) was used to assess changes in hope during the course of treatment. The SHS consists of six items, three that measure agency (e.g., “At the present time, I am energetically pursuing my goals” & “At this time, I am meeting the goals that I have set for myself”) and three that measure pathways (e.g., “There are lots of ways around any problem that I am facing now” & “I can think of many ways to reach my current goals”). The SHS is highly correlated with trait measures of hope (Snyder et al., 1996), and was chosen for use in the present study as the SHS has previously been demonstrated to be more sensitive to intraindividual changes in hope than trait measures, and has previously been used to examine changes in hope during psychotherapy (e.g., Cheavens et al., 2006). In the present study, baseline levels of hope (r = .25, p < .01) and session four levels of hope (r = .28, p < .01) exhibited small to moderate positive correlations with expectancy ratings at session 2 as measured by the CEQ. The internal consistency of the SHS was high at each assessment (Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .89 to .93).

Clinician Rated Anxiety.

Clinician rated levels of anxiety were assessed using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA; Hamilton, 1959). The HAMA is clinician rated measure that has been used extensively in clinical trials of CBT for anxiety, and provides an overall rating of symptom severity across diagnostic boundaries. The HAMA assessments were conducted by independent evaluators who were blind to condition and followed the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (Shear, Vander Bilt, & Rucci, 2001).

Self-Reported Anxiety.

Self-reported levels of anxiety were assessed using the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (Norman, Cissell, Means-Christensen, & Stein, 2006). The OASIS is a five item measure that captures both anxiety symptom frequency/severity (e.g. “In the past week, when you have felt anxious, how intense or severe was your anxiety”) and the associated impairment related to anxiety symptoms (e.g., “In the past week, how much did your anxiety interfere with your ability to do the things you needed to do at work, at school, or at home?”). The OASIS was designed to provide a brief measure of anxiety that can be used across diagnostic boundaries and has been shown to be sensitive to changes in anxiety during CBT (e.g., Barlow et al., 2017). The internal consistency of the OASIS was high at each assessment (Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .83 to .88).

Analytic Plan

All analyses were conducted using Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998 –2016) and robust maximum likelihood estimation. Missing data in all models was handled by using multiple imputation procedures in which 1000 imputed datasets were calculated using Mplus, and then analyses were conducted using the imputed datasets. Changes in hope within treatment conditions were first examined by calculating effect sizes (standardized mean gain; ESsg) that accounted for the correlations in hope between assessment points. As a preliminary analysis, a series of longitudinal measurement invariance models were examined to ensure that changes in hope during treatment represented true changes in hope and not merely changes in the measurement of hope across time. These models supported longitudinal measurement invariance of hope across time.

Latent growth curve (LGC) modeling was then used to characterize the overall trajectories of change in hope, how changes in hope varied between CBT treatment conditions and the waitlist condition, and the extent to which changes in hope mediated the effects of CBT treatment on changes in anxiety. For all LGC analyses, shape factors were specified such that the slope factor was centered on the baseline assessment, the post-treatment assessment loading was fixed at 1.0, and intermediate assessment loadings were freely estimated. The slope factors in the LGC models, therefore, captured the overall intraindividual changes from baseline to post-treatment and allowed interindividual differences in the trajectories of change in hope. The variances of the intercept and slope factors were freely estimated. This approach to model specification did not impose a specific non-linear trajectory, but did allow for non-linear change trajectories as determined by the data. This analytic approach was chosen to allow us to examine how treatments differed in predicting the overall trajectories of change in hope across the course of treatment and how those trajectories of change in hope covaried with the trajectories of change in anxiety symptoms across the course of treatment.

Model fit for the LGC analyses was evaluated using standard model fit indices: root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973), the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), and the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996). Acceptable model fit was evaluated using standard model fit criteria: RMSEA and SRMR values close to 0.08 or below, and CFI and TLI values close to .95 or above (Hu & Bentler, 1998).

Results

Does Hope Change as a function of CBT?

Our first analyses involve calculated means and intraindividual effect sizes to characterize changes in hope within and across treatment conditions. These calculations were conducted for the UP condition, for the four disorder specific CBT conditions collapsed (SDP), for the overall CBT treatment sample (UP and SDP), and for the waitlist condition. The means of hope (with 95% confidence intervals) and the intraindividual effect sizes by condition across time are reported in Table 1. As expected, results indicated that both disorder specific and transdiagnostic CBT resulted in increases in hope that were statistically significant and moderate to large in effect size magnitude. Based on the confidence intervals of the effect sizes, the changes in hope in CBT conditions were statistically greater than changes in the waitlist condition. Increases in hope were largely maintained in each active treatment condition at the six month follow-up assessment. Levels of hope at the follow-up were statistically significantly greater than baseline levels in each condition.

Table 1.

Means and Intraindividual effect sizes (ESsg) of changes of Hope (with 95% confidence intervals) by condition across time

| M (95%CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeframe | CBT (n=179) | UP (n=88) | SDP (n=91) | WL (n=44) |

| Baseline | 28.09 (26.82 : 29.36) | 29.39 (27.51 : 31.27) | 26.83 (25.15 : 28.51) | 28.45 (26.00 : 30.90) |

| Session 4 | 29.87 (28.61 : 31.14) | 31.11 (29.33 : 32.90) | 28.68 (26.91 : 30.44) | 28.94 (26.44 : 31.45) |

| Session 8 | 31.06 (29.75 : 32.36) | 31.65 (29.80 : 33.51) | 30.48 (28.65 : 32.31) | 28.62 (26.08 : 31.16) |

| Session 12 | 32.02 (30.53 : 33.50) | 32.80 (30.74 : 34.86) | 31.26 (29.14 : 33.37) | 29.50 (26.75 : 32.26) |

| Post Treatment | 33.96 (32.59 : 35.33) | 34.76 (32.78 : 36.75) | 33.18 (31.30 : 35.06) | 30.78 (28.02 : 33.54) |

| 6 month follow-up | 32.69 (31.21 : 34.16) | 33.45 (31.29 : 35.60) | 31.96 (29.96 : 33.96) | |

| ESsg (95% CI) | ||||

| Baseline - Session 4 | 0.21 (0.10 : 0.31) | 0.20 (0.05 : 0.35) | 0.22 (0.08 : 0.36) | 0.06 (−0.13 : 0.25) |

| Baseline - Session 8 | 0.38 (0.26 : 0.50) | 0.25 (0.10 : 0.41) | 0.43 (0.24 : 0.61) | 0.02 (−0.20 : 0.25) |

| Baseline - Session 12 | 0.41 (0.28 : 0.54) | 0.36 (0.19 : 0.53) | 0.47 (0.27 : 0.67) | 0.01 (−0.25 : 0.26) |

| Baseline - Post-Treatment | 0.65 (0.49 : 0.81) | 0.58 (0.38 : 0.78) | 0.73 (0.49 : 0.97) | 0.26 (0.04 : 0.48) |

| Baseline - 6 month follow-up | 0.49 (0.35 : 0.62) | 0.42 (0.22 : 0.61) | 0.56 (0.37 : 0.75) | |

Notes: CBT = combined active treatment sample; UP = Unified Protocol; SDP = Single Disorder CBT protocols; WL = Waitlist

When does Hope Change in CBT?

We next examined the magnitude of the effect size changes in each condition to understand when changes in hope occurred in CBT and the waitlist condition. As expected, in each CBT condition there was a small effect size (ESsg ~ .20) increase in hope early in treatment from the baseline assessment to the fourth week of treatment. Although session by session changes in hope were not assessed, these results indicate that hope began to demonstrably increase in participants early in treatment prior to when the majority of symptom change occurred (Barlow et al., 2017), which is consistent with the premise that hope may be a transdiagnostic mechanism that helps promote subsequent changes in anxiety symptoms during treatment. In contrast, the change in hope from baseline to week four of the waitlist condition was negligible and not statistically significant. Changes in hope in the waitlist condition were only present starting during the final four weeks before the post-waitlist assessment, which may reflect the fact that participants knew that they would begin CBT immediately following the completion of the waitlist condition.

Does Hope Change consistently across CBT protocols and diagnoses?

We next examined how changes in hope varied across CBT conditions and principal diagnoses to help understand the extent to which changes in hope may be consistent across the treatment of anxiety. The small early increases in hope were consistent across both transdiagnostic and disorder specific CBT protocols, and the overall moderate to large effect size increase in hope was also consistent across both transdiagnostic and disorder specific CBT protocols. The magnitude of changes in hope was generally similar when breaking out by treatment condition more specifically: UP ESsg = .58 (95% CI .38 : .78); MAP ESsg = .56 (95% CI .08 : 1.04); MAW ESsg = .60 (95% CI .12 : 1.08); MSA ESsg = .97 (95% CI .51 : 1.43); MOCD ESsg = .55 (95% CI .05 : 1.04). The magnitude of changes in hope was also generally similar when examining changes in hope across the four anxiety disorders examined: panic disorder ESsg = .64 (95% CI .32: 0.96); generalized anxiety disorder ESsg = .55 (95% CI .27 : .83); social phobia ESsg = .82 (95% CI .50 : 1.13); obsessive compulsive disorder ESsg = .49 (95% CI .21 : .78). For all CBT conditions and principal diagnoses, the overall changes in hope were moderate to large in effect size magnitude and statistically significant.

Trajectories of Change in Hope

A series of LGC models was specified next to examine the overall trajectories of change in hope, how changes in hope varied as a function of treatment, and how changes in hope related to changes in anxiety. First, an unconditional model was specified to characterize change just in the participants in active treatment. The model fit statistics for this model were mostly good: (χ2 (df = 7) = 26.7, p > .05, RMSEA = 0.12, TLI = .97, CFI = .95; SRMR = .08). The intercept (M = 27.97; SE = .65) and slope (M = 5.73; SE .82) were both statistically significant and indicated that hope generally increased across the course of treatment. The slope loadings, which can be roughly interpreted as the proportion of change that has occurred by a given assessment point, were 0 (baseline), .32 (session 4), .57 (session 8), .71 (session 12), and 1.0 (post-treatment). These results indicate that changes in hope were occurring across all phases of treatment, but that the majority of change occurred in the first half of treatment.

A conditional LGC model was then specified with a dummy coded variable representing treatment (0 = waitlist; 1 = CBT treatment) predicting the slope factor for hope. The model fit statistics for this LGC were generally good (χ2 (df = 12) = 68.65, p > .05, RMSEA = 0.10, TLI = .97, CFI = .96; SRMR = .07). The unstandardized effect of treatment vs waitlist on hope in this model was statistically significant (b = 3.54; se = 1.33; p < .05), and indicated that treatment resulted in greater positive changes in hope relative to waitlist. The partially standardized path coefficient for the effect of treatment vs waitlist on hope, which can be interpreted in the Cohen’s d metric, indicated that the changes in hope as a function of treatment were large in magnitude (β = .60, se = .22).

A second conditional LGC model was then specified with a dummy coded variable representing type of treatment (0 = disorder specific CBT; 1 = transdiagnostic CBT) predicting the slope factor for hope. The model fit statistics for this LGC were also generally good (χ2 (df = 12) = 33.75, p > .05, RMSEA = 0.10, TLI = .97, CFI = .96; SRMR = .10). The unstandardized effect of treatment on hope in this model was not statistically significant (b =−.25; se = 1.33; p > .05), but indicated that transdiagnostic CBT resulted in a slightly smaller increase in hope relative to disorder specific CBT. The partially standardized path coefficient for the effect of type of treatment on hope indicated that the changes in hope as a function of transdiagnostic or disorder specific treatment were small in magnitude (β = −.04, se = .22).

Associations in Change

Two parallel process LGC were then specified to examine how trajectories of change in hope related to trajectories of change in anxiety in the active treatment sample through the post-treatment assessment. First, the associations in change between hope and clinician rated anxiety (HAMA) were examined. The model fit (χ2 (df = 31) = 71.91, p > .05, RMSEA = 0.09, TLI = .95, CFI = .97; SRMR = .05) was adequate and there was a large negative association (r = −.85, se = .11, p <.001) between the hope and anxiety slopes, and a moderate, negative association (r = −.26, se = .09, p <.01) between the hope and anxiety intercepts. The associations in change between hope and self-reported anxiety (OASIS) were examined next. The model fit (χ2 (df = 31) = 87.68, p > .05, RMSEA = 0.10, TLI = .94, CFI = .96; SRMR = .06) was again adequate and the pattern of associations was consistent with the first parallel process model. There was a large, negative association (r = −.77, se = .10, p <.001) between the hope and anxiety slopes, and a large, negative association (r = −.53, se = .07, p <.001) between the hope and anxiety intercepts. The results of these parallel process models, therefore, demonstrate that higher hope is related to lower baseline levels of anxiety, that there is a strong relationship between changes in hope and changes in anxiety such that greater increases in hope are associated with greater decreases in anxiety, and that these relationships hold across both self-reported and clinician rated anxiety outcomes.

Two parallel process LGC were then specified to examine how trajectories of change in hope related to trajectories of change in anxiety in the active treatment sample through the follow-up assessment. First, the associations in change between hope and clinician rated anxiety (HAMA) were examined. The model fit (χ2 (df = 51) = 110.49, p > .05, RMSEA = 0.08, TLI = .95, CFI = .96; SRMR = .06) was adequate and there was a large negative association (r = −.84, se = .10, p <.001) between the hope and anxiety slopes, and a moderate, negative association (r = −.28, se = .09, p <.01) between the hope and anxiety intercepts. The associations in change between hope and self-reported anxiety (OASIS) were examined next. The model fit (χ2 (df = 51) = 142.72, p > .05, RMSEA = 0.10, TLI = .92, CFI = .94; SRMR = .07) was again adequate and the pattern of associations was consistent with the first parallel process model. There was a large, negative association (r = −.75, se = .09, p <.001) between the hope and anxiety slopes, and a large, negative association (r = −.56, se = .07, p <.001) between the hope and anxiety intercepts. The relationship between changes in hope and changes anxiety therefore appears consistent across the acute treatment phase and through the six month follow-up assessment.

Indirect Effects of Treatment on Anxiety via Hope

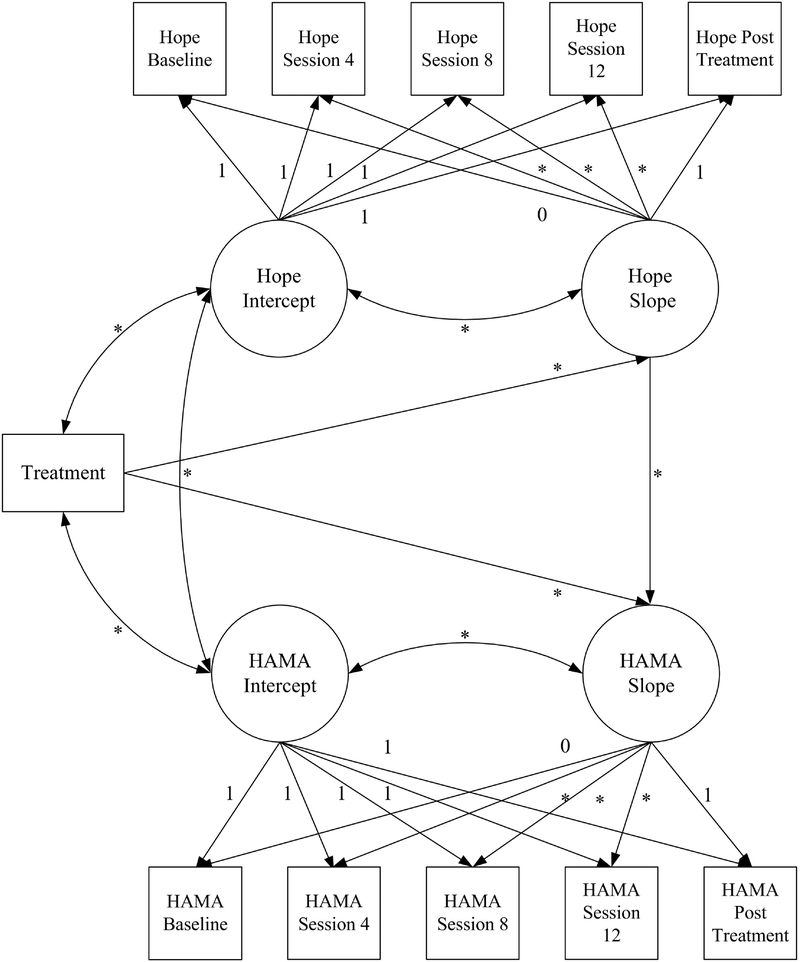

Our final analyses examined the indirect effect of treatment on intraindividual changes in clinician rated and self-reported anxiety via intraindividual changes in hope. Two parallel process latent growth curve models were specified to examine the indirect effects of hope on each anxiety outcome. Figure 1 provides an example of how these models were specified. For both models, the slope of the anxiety outcome was regressed onto the treatment dummy code variable (1 = disorder specific or transdiagnostic CBT; 0 = waitlist) and the slope of hope. The slope of hope was regressed onto the treatment dummy code variable. The intercepts for both constructs were allowed to freely covary as were the slopes of each construct with the intercept of that construct. The indirect effect (ab) was then calculated using the product of the effect of treatment on intrandividual trajectories of change in hope (a) and the effect of changes in hope on intrandividual trajectories of change in the anxiety disorder outcomes (b). The statistical significance of the indirect effect was evaluated with the product of coefficients approach by using the Mplus MODEL INDIRECT command.

Figure 1.

Example parallel process latent growth curve model examining the indirect effect of treatment on clinician rated anxiety (HAMA) via hope

The results of these two models are presented in Table 2. The model fit for both models was acceptable. The effect of CBT treatment on hope (a) and the effects of changes in hope on changes in anxiety (b) was statistically significant (p < .01) and large in effect size magnitude based on the partially standardized and completely standardized parameter estimates, respectively. The indirect effect of CBT treatment on change in anxiety via changes in hope was also statistically significant based on the product of coefficients for both clinician rated and self-reported anxiety. The proportion of variance (R2) explained in both the clinician rated and self-reported anxiety was greater than .60, indicating that the combined effect of the treatment dummy code variable, and the slope factor of hope together predicted more than 60% of the variance in the changes in anxiety across the course of treatment. Additional models were examined in which the anxiety slope factors were only regressed on treatment to determine the proportion of variance that was specifically due to the inclusion of the hope slope as a predictor of changes in anxiety. These incremental R2 are presented in Table 2 and were large for both clinician rated (.41) and self-reported (.61) anxiety. The large magnitude of these incremental effects underscore the importance of intraindividual changes in hope during CBT in predicting intraindividual changes in anxiety, and that these effects are maintained when collapsing across distinct CBT treatment protocols and for individuals with different principal diagnoses.

Table 2.

Results from parallel-process latent growth curve models examining the indirect effect of treatment on clinician rated (HAMA) and self-reported (OASIS) anxiety via hope

| Parameter Estimate | HAMA | OASIS |

|---|---|---|

| CBT Treatment → Hope Slope (a) | ||

| Unstandardized | 3.54** | 3.61** |

| Standard Error | 1.33 | 1.33 |

| Partially Standardized | 54** | .60** |

| Completely Standardized | 22** | 24** |

| Hope Slope → Anxiety Slope (b) | ||

| Unstandardized | −.064*** | .37*** |

| Standard Error | .012 | 0.06 |

| Completely Standardized | −.74*** | −.81*** |

| CBT Treatment → Anxiety Slope (c’) | ||

| Unstandardized | −2.51* | −1.88** |

| Standard Error | 1.09 | 0.57 |

| Partially Standardized | −.45** | −.69** |

| Completely Standardized | −.18* | . 27** |

| Indirect Effect | ||

| ab | −2.26* | −1.33* |

| Standard error (ab) | .91 | .54 |

| Variance Explained (R2) Anxiety Slope | .64 | .83 |

| Incremental R2 of Hope Slope on Anxiety Slope | .41 | .61 |

| Model fit | ||

| χ2 | 98 12*** | 142.22*** |

| df | 41 | 42 |

| RMSEA | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| CFI | .95 | .94 |

| TLI | 0.97 | 0.93 |

| SRMR | .05 | .08 |

Note. HAMA = Hamilton Anxiety Scale; OASIS = Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale.

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated that CBT is an effective treatment for multiple anxiety and mood disorders (Hofmann, Asnaani, Bonk, Sawyer, & Fang, 2012). Thus, there has increasingly been a push towards recognizing mechanisms of change in order to explain why CBT is effective, with the goal of refining and bolstering the effectiveness of this treatment modality. Some research has focused on identifying the unique “active ingredients” promoting change within specific CBT modalities for particular disorders. However, it has long been recognized that, while evidence does not indicate that common factors fully explain recovery during psychotherapy, there are core elements and processes of empirically supported treatments that may partially account for recovery across different treatment modalities and across a variety of disorders (Frank & Frank, 1991; Norcross & Wampold, in press; Snyder et al., 2000). An emerging literature has indicated hope as a promising transdiagnostic mechanism of recovery, and the current study extends this research by examining how changes in hope influence changes in symptoms throughout the course of therapy, beyond simple pre-and post-treatment comparisons.

The results of the present study indicate that hope increases during the course of CBT, and increases in hope were greater for those in active treatment than for those in the waitlist comparison. The magnitude of these changes in hope were consistent across disorder specific CBT protocols and transdiagnostic treatment for the four anxiety disorders examined. This is consistent with theories of hope as a mechanism that promotes symptom change across treatment modalities. Additionally, the findings corroborate existing evidence that CBT promotes positive outcomes in general, reflecting greater reductions in anxiety symptoms for those in active treatment than for those in the waitlist comparison.

Furthermore, the present study indicates that changes in hope are associated with changes in anxiety symptoms. The magnitude of the associations between changes in hope and changes in anxiety were large and suggest not only that changes in hope predict symptom recovery, but that hope could be a particularly important factor in predicting recovery across different treatment protocols. It is important to note, however, that while these findings provide strong evidence that hope may be an important factor in predicting recovery across different protocols and diagnoses, they do not suggest that hope is the sole mechanism of recovery during CBT and it is likely that hope has a bidirectional influence and reinforcing effect on other coping skills and processes (e.g., mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal) that have previously been demonstrated to be important mechanisms of change during CBT for anxiety disorders.

For those in active treatment, changes in hope started to occur within the first four sessions of treatment. Thus, changes in hope occurred before the majority of symptom change and this finding was consistent across CBT protocols and transdiagnostic treatment. This is important as demonstrating temporal precedence of change is a crucial issue in identifying mechanisms of change (Kazdin, 2007). While some increases in hope were observed for those in the waitlist comparison, these changes were only significant before the final assessment point, and may reflect participants’ knowledge that they would begin treatment immediately following the waitlist condition. Although speculative, observed increases in hope in the early phase of treatment may help to explain the phenomenon of early rapid response in CBT participants, which is itself a positive prognostic indicator of post-treatment and follow-up outcome (Brady, Warnock-Parkes, Barker, & Ehlers, 2015).

Strengths of this study include the large clinical trial that allowed for the examination of how hope changed and related to symptom recovery across multiple diagnoses. The current study measured trajectories of change throughout the course of therapy, not just during pre-and post-treatment, which allows for a clearer understanding of exactly when changes in hope occur during CBT treatment. The examination of changes in hope during both transdiagnostic and single disorder CBT protocols also provides strong evidence that increases in hope during treatment are not unique to any one form of CBT and provide some of the most promising evidence to date that promoting hope may be a transdiagnostic process in evidence based treatments for anxiety disorders. It is also important to emphasize that model (i.e., CBT) unique and common factors are not mutually exclusive treatment elements and likely interact dynamically throughout a course of treatment.

In addition, the consistent finding of an indirect effect of treatment on changes in both clinician rated and self-reported anxiety also strengthen conclusions regarding the role of hope as a potential broadly relevant mechanism in predicting anxiety as results hold across multiple methods of assessing intraindividual changes in symptoms during treatment. The observed relationships appear to be robust across different methods of assessment.

Although the present study provided promising evidence regarding timing and the consistency of changes in hope during CBT treatment, the analytic strategy and assessment schedule of outcomes are nevertheless important limitations in understanding temporal dependencies in change of hope and change in symptoms. Because outcomes were only assessed every four sessions, we were not able to conduct more fine-grained analyses of session by session changes in hope and how they may predict changes in symptoms prior to subsequent sessions. Quantifying session by session changes and using analytic techniques such as bivariate latent difference score models in future studies could strengthen conclusions regarding the causal role of changes in hope promoting subsequent changes in anxiety. The LGC models used in the present study provide strong evidence that trajectories of change in hope during treatment are robustly associated with trajectories of change in anxiety symptoms, but they do not clearly demonstrate that early intraindividual changes in hope drive subsequent changes in anxiety. More research is therefore needed to establish temporal precedence of changes in hope in relation to anxiety during CBT, which would allow for more definitive conclusions regarding the role of hope as a causal mechanism of change. In the present study, our analytic approach initially consisted of effect sizes and the LGC analyses reported, but we also subsequently attempted to conduct bivariate LDS models in order to further explore bidirectional influences and temporal dependencies of change. Unfortunately, the bivariate LDS analyses had estimation issues and we were not able to obtain valid and stable results due to convergence issues so the results of those additional analyses are not reported.

The present study also focuses primarily on intra-individual patterns of change in overall anxiety symptoms rather than changes in diagnostic status, so our findings do not speak to what amount of change in hope may be necessary to achieve subclinical levels of different anxiety disorders or complete remission of symptoms. Other techniques such as latent growth mixture modeling may help elucidate how changes in hope may relate to patterns of treatment response (e.g. non-responders, early responders). In addition, it may be fruitful to compare the temporal course of changes in the different components of hope (i.e., pathways and agency) and how these changes may differentially influence changes in anxiety symptoms. Given the design of the clinical trial we also were not able to compare the effects of treatment on hope compared to the waitlist condition through follow-up as waitlist participants immediately initiated treatment following their post-waitlist assessment and therefore did not complete a six month follow-up assessment. Another important limitation is that the sample used in the present study was relatively homogenous in terms of race/ethnicity and education, so it will be important to examine the role of hope during CBT in more diverse populations.

Future research should also examine the role of other potential core elements or processes that are possibly consistent across evidence based treatments such as self-efficacy or working alliance quality. Demonstrating the unique contribution of hope above and beyond other positive psychology constructs such as optimism or processes often examined in CBT trials such as expectancy and perceived control will help to clarify the specific influence of different aspects of positive thinking in promoting recovery during CBT. It is likely that some portion of the observed effects could be explained by shared variance with these other constructs. Hope and other core mechanisms/processes may also promote beneficial changes in other outcomes beyond reductions in symptoms, so examining the link between changes in hope and increases in well-being or other markers in positive functioning will be an important future direction.

Overall, the findings provide supporting evidence for hope as a transdiagnostic mechanism that promotes positive changes in symptoms across treatment modalities. The present study builds on previous research by demonstrating that changes in hope and associated reductions in anxiety were consistent across different CBT protocols for different disorders, as well as in the context of transdiagnostic treatment. Furthermore, the findings support the role of hope as a mechanism of change by indicating a strong relationship between changes in hope and reductions in anxiety and that changes in hope partially mediate the effects of treatment on symptom recovery. Thus, our findings speak to the importance of how hope and other core processes may improve our understanding of how patients recover from anxiety disorders during empirically supported treatments.

Highlights.

Hope is cognitive trait that predicts resilience and recovery from anxiety disorders

This study examined hope as a transdiagnostic mechanism of change in CBT

Transdiagnostic and four disorder specific CBTs all produced large increases in hope

Intraindividual changes in hope were robust predictors of symptom trajectories

Hope is a promising transdiagnostic mechanism of change across disorders and protocols

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH090053; PI D. H. Barlow). The funding agency had no role in the analysis or interpretation of the data. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alarcon GM, Bowling NA, & Khazon S (2013). Great expectations: A meta-analytic examination of optimism and hope. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(7), 8212013 827. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnau RC (2018). Hope and anxiety In Gallagher MW & Lopez SJ, Oxford Handbook of Hope (pp. 2332013242). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnau RC, Rosen DH, Finch JF, Rhudy JL, & Fortunato VJ (2007). Longitudinal effects of hope on depression and anxiety: A latent variable analysis. Journal of Personality, 75(1), 43201364. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH (2002). Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH (Ed.). (2014). Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, & Craske MG (2006). Mastery of your anxiety and panic. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Bullis JR, Gallagher MW, Murray-Latin H, Sauer-Zavala S, … & Ametaj A (2017). The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders compared with diagnosis-specific protocols for anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 74(9), 8752013884. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 28, 97–104. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady F, Warnock-Parkes E, Barker C, & Ehlers A (2015). Early in-session predictors of response to trauma-focused cognitive therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 75, 40201347. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheavens JS, Feldman DB, Gum A, Michael ST, & Snyder CR (2006a). Hope therapy in a community sample: A pilot investigation. Social Indicators Research, 77(1), 61201378. doi: 10.1007/s11205-005-5553-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheavens JS, Feldman DB, Woodward JT, & Snyder CR (2006b). Hope in Cognitive Psychotherapies: On Working With Client Strengths. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20(2), 1352013145. doi: 10.1891/jcop.20.2.135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino MJ, Visla A, Coyne AE, & Boswell JF (2018). A meta-analysis of the association between patients’ early treatment outcome expectation and their posttreatment outcomes. Psychotherapy, 55, 4732013485. doi: 10.1037/pst0000169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, & Barlow DH (2006). Mastery of your anxiety and worry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, & Borkovec TD (2000). Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31(2), 73201386. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DB, & Dreher DE (2012). Can hope be changed in 90 minutes? Testing the efficacy of a single-session goal-pursuit intervention for college students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(4), 7452013759. doi: 10.1007/s10902-011-9292-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Yadin E, & Lichner TK (2012). Exposure and response (ritual) prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder: Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Frank J (1968). The role of hope in psychotherapy. International Journal of Psychiatry, 5(5), 3832013395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JD, & Frank JB (1993). Persuasion and healing: A comparative study of psychotherapy. Baltimore, MD: JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW (2017). Transdiagnostic mechanisms of change and cognitive-behavioral treatments for PTSD. Current Opinion in Psychology, 14, 90201395. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, Bentley KH, & Barlow DH (2014). Perceived control and vulnerability to anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(6), 5712013584. doi: 10.1007/s10608-014-9624-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, & Lopez SJ (2009). Positive expectancies and mental health: Identifying the unique contributions of hope and optimism. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 5482013556. doi: 10.1080/17439760903157166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, & Lopez SJ (Eds.). (2018). The Oxford Handbook of Hope. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, Naragon-Gainey K, & Brown TA (2014). Perceived control is a transdiagnostic predictor of cognitive–behavior therapy outcome for anxiety disorders. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 38(1), 10201322. doi: 10.1007/s10608-013-9587-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, Payne LA, White KS, Shear KM, Woods SW, Gorman JM, & Barlow DH (2013). Mechanisms of change in cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder: The unique effects of self-efficacy and anxiety sensitivity. Behavior Research and Therapy, 51, 7672013777. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW & Resick PA (2012). Mechanisms of change in cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Preliminary evidence for the differential effects of hopelessness and habituation. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 36, 7502013755. doi: 10.1007/s10608-011-9423-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman R, Schumm JA, & Chard KM (2012). Hope as a change mechanism in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(3), 2702013277. doi: 10.1037/a0024252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haanstra TM, Tilbury C, Kamper SJ, Tordoir RL, Vlieland TPV, Nelissen RG, … & Ostelo RW (2015). Can optimism, pessimism, hope, treatment credibility and treatment expectancy be distinguished in patients undergoing total hip and total knee arthroplasty?. PloS one, 10(7), e0133730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin DM, Weitzman ML, & Otto MW (2010). Therapeutic alliance and common factors in treatment In Otto MW & Hofmann SG (Eds.), Avoiding treatment failures in the anxiety disorders (pp. 51201366). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton MA (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32(1), 50201355. doi: /10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassija CM, Luterek JA, Naragon-Gainey K, Moore SA, & Simpson T (2012). Impact of emotional approach coping and hope on PTSD and depression symptoms in a trauma exposed sample of veterans receiving outpatient VA mental health care services. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal, 25(5), 5592013573. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2011.621948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AM, Feldman GC, Beevers CG, Laurenceau JP, Cardaciotto L, & Lewis Smith J (2007). Discontinuities and cognitive changes in an exposure-based cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 409–421. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, & Hofmann SG (Eds.). (2018). Process-based CBT: the science and core clinical competencies of cognitive behavioral therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, Sawyer AT, & Fang A (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 36(5), 4272013440. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope DA, Heimberg RG, & Turk CL (2010). Managing social anxiety: A cognitive-behavioral therapy approach. New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1998). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 4242013453. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irving LM, Snyder CR, Cheavens J, Gravel L, Hanke J, Hilberg P, & Nelson N (2004). The relationships between hope and outcomes at the pretreatment, beginning, and later phases of psychotherapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 14(4), 4192013443. doi: 10.1037/1053-0479.14.4.419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, & Sörbom D (1996). LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1201327. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long LJ Gallagher MW (2018). Hope and posttraumatic stress disorder In Gallagher MW & Lopez SJ, The Oxford Handbook of Hope (pp. 2332013242). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magaletta PR, & Oliver JM (1999). The hope construct, will, and ways: Their relations with self-efficacy, optimism, and general well‐being. Journal of clinical psychology, 55(5), 5392013551. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques SC, & Gallagher MW (2017). Age differences and short-term stability in hope: Results from a sample aged 15 to 80. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 53, 1202013126. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2016). Mplus 8.0 [Computer software]. Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC, & Wampold BE (Eds.) (in press). Psychotherapy relationships that work: Evidence-based responsiveness (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Hami Cissell S, Means‐Christensen AJ, & Stein MB (2006). Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). Depression and Anxiety, 23(4), 2452013249. doi: 10.1002/da.20182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand KL (2018). Hope self-efficacy, and optimism: Conceptual and empirical differences In Gallagher MW& Lopez SJ, The Oxford Handbook of Hope (pp. 45201358). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, & Feuer CA (2002). A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 8672013879. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.70.4.867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritschel LA & Sheppard CS (2018). Hope and depression. In M. W. Gallagher & S. J. Lopez, Oxford Handbook of Hope (pp. 2092013220). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, & Carver CS (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4(3), 219. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Vander Bilt J, Rucci P, Endicott J, Lydiard B, Otto MW, … & Frank DM (2001). Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A). Depression and Anxiety, 13(4), 1662013178. doi: 10.1002/da.1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 2492013275. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Ilardi SS, Cheavens J, Michael ST, Yamhure L, & Sympson S (2000). The role of hope in cognitive-behavior therapies. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 24(6), 7472013762. doi: 10.1023/A:1005547730153Y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Ilardi SS, Michael ST, & Cheavens J (2000). Hope theory: Updating a common process for psychological change In Snyder CR & Ingram RE (Eds.), Handbook of psychological change: Psychotherapy processes & practices for the 21st century (pp. 1282013153). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Sympson SC, Ybasco FC, Borders TF, Babyak MA, & Higgins RL (1996). Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 321. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25, 1732013180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, & Lewis C (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38, 10. doi: 10.1007/BF02291170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]