Abstract

Objective This study evaluates penicillin allergy during pregnancy to estimate the proportion that could benefit from penicillin allergy testing.

Study Design Retrospective cohort study of women with penicillin allergy that delivered from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2018.

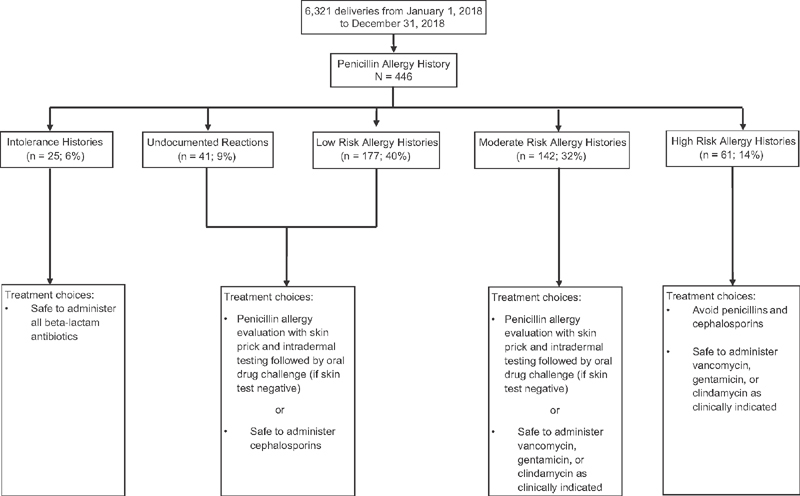

Results Among 6,321 deliveries, 446 (7%) were identified with penicillin allergy. Nine percent (41/446) had no documentation of allergy severity. Allergies associated with intolerance, low, moderate, or high risk of anaphylaxis were reported in 6% (25/446), 40% (177/446), 32% (142/446), and 14% (61/446), respectively. Nearly 74% (330/446) received an antibiotic either antepartum, at delivery, or within 6 weeks of postpartum. The majority of women, 81% (360/446) (i.e., undocumented reactions, low, or moderate risk of anaphylaxis) would have been eligible for penicillin allergy testing. Greater appropriate utilization of antibiotics occurred in women with a high 80% (39/49) or moderate risk of anaphylaxis 70% (79/112) versus low risk of anaphylaxis 55% (64/117), history of intolerance 40% (8/20), or undocumented reaction 19% (6/32), p ≤ 0.01.

Conclusion Most women who report a penicillin allergy during pregnancy would be candidates for penicillin allergy testing. With the high rate of antibiotic interventions in pregnant women who report a penicillin allergy, consideration should be given for penicillin allergy assessment.

Keywords: penicillin allergy, pregnancy, penicillin allergy skin testing

The occurrence of hypersensitivity reactions due to antibiotics, such as penicillin, leads to the avoidance of standard antimicrobial interventions. Although antibiotic allergies are generally documented in the medical record, the reactions associated with these allergies are often not explored or reported by health care providers, and patients may receive unnecessarily broad spectrum or suboptimal antibiotics. 1 In obstetrical populations, depending upon the subgroup of women evaluated, penicillin allergy is reported to range from 8 to 13%. 2 3 In the absence of applicable evaluation for penicillin allergy, pregnant women providing a history of penicillin allergy must continue to avoid penicillin. In women who report a penicillin allergy, the inability to utilize a β-lactam antibiotic during pregnancy has been associated with less effective intrapartum neonatal group B streptococcus (GBS) prophylaxis, a greater rate of cesarean surgical site infection and increased risk of postpartum endometritis. 4 5 6 However, when penicillin allergy testing is performed in individuals who report a history of a penicillin allergy, the majority do not exhibit a positive reaction. 7 Despite penicillin allergy testing being shown to be safe during pregnancy, it is rarely performed. 8 9

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology encourages the routine performance of penicillin skin testing for patients with a history of a penicillin allergy. 10 Recently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has advocated that if penicillin allergy testing is available, it is safe to perform during pregnancy and can be beneficial for all women who report penicillin allergies, particularly those that are suggestive of being immunoglobulin E mediated or of unknown severity. 11

Currently, there are no estimates of the proportion of pregnant women that report a penicillin allergy, who will require antibiotic therapy during pregnancy and could benefit from penicillin allergy skin testing. Our objective was to evaluate the types of allergic reactions in pregnant women reporting a penicillin allergy to estimate the proportion that could be referred for penicillin allergy testing. A secondary outcome was to evaluate the appropriateness of antibiotic utilization in women who report a penicillin allergy during pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study of women who reported an allergy to penicillin that delivered at the Texas Children's Hospital Pavilion for Women from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2018. The primary outcome was the proportion of pregnant women who would have been eligible for penicillin allergy testing (i.e., report an unknown reaction; low or moderate risk of anaphylaxis). 1 7 Planned secondary outcomes were the rate of antibiotic utilization during the pregnancy and up to 6 weeks of postpartum and appropriateness of antibiotic choice for a given medical indication. Appropriateness of antibiotic choice was defined as the antibiotic recommended by guidelines from ACOG. 11 12 13 14

The electronic health record (Epic), which contains the outpatient prenatal, delivery, and postpartum information, was queried. A discrete data field for “allergies” was searched for any reported allergy to β-lactam antibiotics (e.g., penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin). Sociodemographic and obstetric outcomes were retrieved. Allergies were defined as either “not documented,” history of intolerance, low risk of anaphylaxis, moderate risk of anaphylaxis, or high risk of anaphylaxis ( Table 1 ). 1 7 11 Appropriateness of antibiotics was defined as use of β-lactams for the history of intolerance, cephalosporin for an undocumented reaction or low risk of anaphylaxis, and use of vancomycin, gentamicin, or clindamycin for a moderate or high risk of anaphylaxis as directed by the medical condition or bacterial culture sensitivity result. 11 12 13 14 The Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board gave approval for the study, protocol H-45354. All the analyses employed Microsoft Excel 2013 version for summary statistics. The Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests were used to analyze categorical variables, and Student's t -tests were used to analyze continuous variables. p -Value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1. Adverse drug reaction to penicillin exposure stratified by risk of response a .

| Penicillin allergy history | Reaction reported |

|---|---|

| Intolerance | • Isolated gastrointestinal upset (nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain) • Yeast vaginitis • Headache • Fatigue • Family history of penicillin allergy but no personal history |

| Low-risk anaphylaxis | • Nonurticarial maculopapular rash without systemic symptoms • Unknown childhood history or remote (>10 years ago) reaction |

| Moderate-risk anaphylaxis | • Urticarial rash (hives) • Intense pruritis (itching) |

| High-risk anaphylaxis | • Anaphylaxis • Respiratory distress (shortness of breath, cough, throat tightness, and wheezing) • Bronchospasm (chest tightness) • Immediate flushing • Angioedema (swelling) • Hypotension (loss of consciousness) • Positive penicillin skin test • Reaction to multiple β-lactam antibiotics • Rare delayed reactions such as eosinophilia and systemic symptoms/drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or toxic epidermal necrolysis |

Data from Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: A review. JAMA 2019; 321: 188–99. 7 Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phillips E. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet 2019; 393: 183–98. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Prevention of group B streptococcal early-onset disease in newborns. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 782. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 134: e19–40.

Results

Between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018, a total of 6,321 deliveries occurred of which 448 (7%) women reported a penicillin allergy. Two of these women had no prior history of an allergy to penicillin, but had an allergic reaction during the current pregnancy when given a β-lactam antibiotic and were excluded from the analysis. Among 446 electronic health records analyzed, allergies were recorded at the initial obstetrical encounter in 100% of patients at a mean gestational age of 15.3 ± 7.6 weeks of gestation. The mean age ± standard deviation of women was 32.1 ± 7.3 years. Self-described race or ethnicity was non-Hispanic white ( n = 264 [59%]), Hispanic ( n = 93 [21%]), non-Hispanic black ( n = 64 [14%]), Asian ( n = 21 [5%]), or other ( n = 4 [1%]). No statistical differences were noted in age, race, or ethnicity between the five categorizations of reactions to penicillin exposure (data not shown).

A total of 9% (41/446) of women had no documentation of the allergy severity. Histories of intolerance were noted in 6% (25/446) of women. Allergies associated with a low, moderate, or high risk of anaphylaxis were reported in 40% (177/446), 32% (142/446), and 14% (61/446), respectively ( Fig. 1 ). Reactions reported with intolerance histories were isolated gastrointestinal upset (nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain), headache, yeast vaginitis; 92% (23/25) or family history of penicillin allergy, but no personal history or 8% (2/25). Reactions reported in low risk of anaphylaxis were nonurticarial maculopapular (morbilliform) rash without systemic symptoms 70% (125/177) and reported histories with no recollection of symptoms or treatment 30% (52/177). Reactions reported in moderate risk of anaphylaxis were urticarial rash (hives) 96% (137/142) or intense pruritis 4% (5/142). Reactions reported in high risk of anaphylaxis were anaphylaxis 44% (27/61), angioedema 39% (24/61), respiratory distress 11% (7/61), seizure 3% (2/61), and positive penicillin skin testing 2% (1/61). Of women labeled with a history of a penicillin reaction, 81% (360/446) (i.e., undocumented reactions; low or moderate risk of anaphylaxis) would have been eligible for penicillin allergy testing.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patients analyzed as classified by reported allergy type. Treatment choices are data available from Blumenthal et al 1 and Shenoy et al. 7

About 330 or 74% (330/446) of women received an antibiotic antepartum, at delivery, or within 6 weeks of postpartum. Of those that received antibiotics, 42% (137/330) of undocumented reactions and low-risk allergy women had a clinical indication that a β-lactam agent would have been preferred if a penicillin allergy was not reported. The three most common indications for dispensing antibiotics were surgical prophylaxis at the time of cesarean delivery 44% (145/330), intrapartum prophylaxis for GBS 28% (93/330), and urinary tract infection 9% (30/330). Of women that received an antibiotic, 25% (82/330) had two or more indications for antibiotic administration.

Among all women, 59% (196/330) received an appropriate antibiotic. A greater portion of appropriate utilization of antibiotics occurred in women with a high risk of anaphylaxis 80% (39/49) when compared with either low risk of anaphylaxis 55% (64/117), p < 0.01; history of intolerance 40% (8/20), p < 0.01; or an undocumented reaction 19% (6/32), p < 0.01. Similarly, a larger portion of appropriate utilization of antibiotics occurred in those with a moderate risk of anaphylaxis 70% (79/112) when compared with either low risk of anaphylaxis 55% (64/117), p = 0.01; history of intolerance 40% (8/20), p = 0.01; or an undocumented reaction 19% (6/32), p < 0.01. In contrast, the more common indications for giving an inappropriate antibiotic by the type of allergic reaction occurred during surgical prophylaxis at the time of cesarean delivery or intrapartum prophylaxis for maternal colonization with GBS. For cesarean delivery surgical prophylaxis, women with undocumented reactions 58% (15/26) or a low-risk allergy 58% (31/53) received gentamicin and clindamycin when a cephalosporin would have been indicated. Whereas women with a moderate 70% (23/33) or high-risk allergy 50% (5/10) were given a cephalosporin when either vancomycin, gentamicin, or clindamycin should have been administered. Similarly, in women being administered intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis for colonization with GBS, 23% (6/26) with an undocumented penicillin reaction and 32% (17/53) with a low-risk allergy received clindamycin or vancomycin when a cephalosporin should have been administered, whereas women with a moderate 6% (2/33) or high-risk allergy 30% (3/10) were given a cephalosporin, when vancomycin or clindamycin should have been utilized.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that 81% of women who report an allergy to penicillin during pregnancy could be considered candidates for penicillin allergy testing. In light of our findings that (1) nearly three quarters of women who report an allergy to penicillin will require an antibiotic intervention during the peripartum period, (2) the high rate of inappropriate antibiotic selection by health care providers, and (3) the literature reporting that 84% of individuals will have a negative test when penicillin allergy testing is performed 15 prompt referral of pregnant women should be considered for this diagnostic evaluation.

Currently, there are no uniformly accepted allergy risk classification schemes. Hypersensitivity reactions to drugs are often grouped into the classification of hypersensitivity reaction types I to IV by Gell and Coombs. 1 7 A recent review has proposed a risk stratification for penicillin allergy evaluation into a low, moderate, or high-risk history for penicillin allergy evaluation (either direct oral drug challenge vs. skin testing if negative then followed by oral drug challenge). 7 A clinical classification system that would assist obstetric providers to stratify pregnant women into either an intolerance history, low, moderate, or high-risk of anaphylaxis could facilitate both a referral for penicillin allergy testing and more appropriate antibiotic utilization. In the current study, a large portion of obstetric providers (70 - 80%) prescribed antibiotics correctly as recommended by ACOG guidelines to pregnant women with a moderate- or high-risk of anaphylaxis, respectively. This was in contrast with pregnant women (≤55%) with a low risk of anaphylaxis, intolerance histories, or undocumented reaction that received appropriate antibiotic interventions. Studies looking at guideline adherence for GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis in penicillin allergic women have noted similar inappropriate antibiotic administration in 24 to 56% of individuals. 16 17 In these studies, the authors report that commonly clindamycin or vancomycin was given when a cephalosporin would have been indicated, or a cephalosporin when vancomycin was actually most applicable. 3 16 17 We noted similar findings in our study analysis. Whether obstetric providers were trying to err on the side of caution versus a lack of understanding of the risk of anaphylaxis cannot be determined from our current investigation. Prospective assessment is needed to delineate if the outcomes of pregnant women with a reported penicillin allergy might benefit from this specific clinical classification change.

The type and severity of reaction to penicillin in the past, as reported by the individual, are weakly associated with skin test reactivity to penicillin. In adults and children (excluding pregnant women) who report a history of a penicillin allergy, 1 to 8% will exhibit an adverse reaction to a penicillin challenge. 15 Adverse drug reactions to penicillin skin testing are typically not life threatening (hives, itching, nausea, and gastrointestinal upset) with less than 1% experiencing a severe systemic reaction (such as anaphylaxis). 15

Data of adverse drug reactions to penicillin skin allergy testing in pregnant women who report a penicillin allergy is limited. The literature contains 83 pregnant women that have undergone penicillin skin allergy testing. 8 9 Women were tested that had a past index reaction to penicillin of either a low, moderate, or high risk of anaphylaxis. Of these pregnant women, only 6% (5/83) had a positive penicillin skin allergy test. A total of 2.4% (2/83) suffered an adverse drug event while having penicillin skin allergy testing performed. One woman fainted while undergoing penicillin skin allergy testing. Her penicillin skin allergy test result was negative. A second woman experienced a rash after a positive penicillin skin allergy test. In the event that a drug challenge reaction occurs during penicillin skin allergy testing, the typical adjunctive medications used to treat such reactions (antihistamines, epinephrine, glucocorticoids, or bronchodilators) are not contraindicated for use in pregnancy.

Strengths of this study include a linked electronic health record that contained the prenatal, delivery record and postpartum follow-up with access to all medications prescribed during this period. Allergy information was obtained from all patients with greater than 90% having reaction characteristics documented. However, the study is not without limitations. It is unknown how the reactions of rash versus hives in the current study were labeled since this was based on patient reported histories. No previous studies of penicillin allergy reactions in a general obstetrical populations are available for comparison. Cutaneous reactions, including rash and hives, are the most commonly reported hypersensitivity reactions to drugs. 1 In small subgroups of pregnant women colonized with GBS with a penicillin allergy, reported rates of rash and hives are 38 to 50% and 21 to 29%, respectively. 8 9 This is similar to the overall rate of rash (28%, 125/446) and hives (31%, 137/446) noted in the current study. This also is a reflection that there are presently no validated allergy history questionnaires to assist with clinical assessment. Finally, these results are from one single academic institution in the United States; thus, the external validity (i.e., generalizability) to other institutions may be restricted.

Provider education in anaphylaxis risk assessment and optimization of guideline adherence may improve appropriate antibiotic selection in women with a reported penicillin allergy during pregnancy, thus promoting both patient safety and antimicrobial stewardship. While clinician education may be of benefit, penicillin allergy testing could “delabel” the majority of pregnant women with minimal risk, therefore facilitating proper forthcoming antibiotic application and benefit their long-term future health needs.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Presented as an abstract at the Infectious Disease Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology meeting, August 2019, Big Sky, MT.

References

- 1.Blumenthal K G, Peter J G, Trubiano J A, Phillips E J.Antibiotic allergy Lancet 2019393(10167):183–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai S H, Kaplan M S, Chen Q, Macy E M. Morbidity in pregnant women associated with unverified penicillin allergies, antibiotic use, and group B streptococcus infections. Perm J. 2017;21:16–80. doi: 10.7812/TPP/16-080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paccione K A, Wiesenfeld H C. Guideline adherence for intrapartum group B streptococci prophylaxis in penicillin-allergic patients. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:917304. doi: 10.1155/2013/917304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fairlie T, Zell E R, Schrag S. Effectiveness of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(03):570–577. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318280d4f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris B S, Hopkins M K, Villers M S et al. Efficacy of non-beta-lactam antibiotics for prevention of cesarean delivery surgical site infections. AJP Rep. 2019;9(02):e167–e171. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1685503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel A M, Heine R P, Dotters-Katz S K. The effect of non-penicillin antibiotic regimens on neonatal outcomes in preterm premature rupture of membranes. AJP Rep. 2019;9(01):e67–e71. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1683378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shenoy E S, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal K G. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(02):188–199. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macy E. Penicillin skin testing in pregnant women with a history of penicillin allergy and group B streptococcus colonization. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(02):164–168. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philipson E H, Lang D M, Gordon S J, Burlingame J M, Emery S P, Arroliga M E. Management of group B streptococcus in pregnant women with penicillin allergy. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(06):480–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.Penicillin allergy testing should be performed routinely in patients with self-reported penicillin allergy 2016. Available at:https://www.aaaai.org/Aaaai/media/MediaLibrary/PDF%20Documents/Practice%20and%20Parameters/AAAAI-PositionStatement-Penicillin-Allergy-Testing.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2019

- 11.Prevention of Group B Streptococcal Early-Onset Disease in Newborns.ACOG committee opinion no. 782. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist Obstet Gynecol 2019134e19–e41.31241599 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Use of prophylactic antibiotics in labor and delivery.ACOG practice bulletin no. 199. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Obstet Gynecol 2018132e103–e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prelabor rupture of membranes.ACOG practice bulletin no. 188. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Obstet Gynecol 2018131e1–e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Intrapartum management of intraamniotic infection.Committee opinion no. 712. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Obstet Gynecol 2017130e95–e101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox S, Park M A. Penicillin skin testing in the evaluation and management of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106(01):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Critchfield A S, Lievense S P, Raker C A, Matteson K A. Group B Streptococcus prophylaxis in patients who report a penicillin allergy: a follow-up study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(02):1500–1.5E10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briody V A, Albright C M, Has P, Hughes B L. Use of cefazolin for group B streptococci prophylaxis in women reporting a penicillin allergy without anaphylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(03):577–583. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]