Abstract

Purpose

To estimate the rate of pedicle screw malpositioning associated with placing pedicle screws using intraoperative computed tomography (CT)-guided spinal navigation.

Methods

We analysed the records of 219 patients who underwent pedicle screw fixation using O-arm-based navigation. Screw placement accuracy was evaluated on intraoperative CT scans acquired after pedicle screw insertion. Breaches were graded according to the Gertzbein classification (grade 0–III).

Results

Of 1152 pedicle screws included, 47 had pedicle violations noted on intraoperative CT. Pedicle screw violation was noted for 17 of 241 screws placed in the cervical spine (overall breach rate, 7.05%; 3.73% and 3.3% with grade I and II, respectively), for 11 of 300 screws placed in the thoracic spine (overall breach rate, 3.67%; 2%, 1%, and 0.67% with grade I, II, and III, respectively), and for 22 of 611 screws placed in the lumbar spine (overall breach rate, 3.6%; 2.29% and 0.82% with grade I and II, respectively). The rate of accuracy of pedicle screw fixation was 93%, 96.33%, and 96.4% for the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, respectively.

Conclusions

Using O-arm-based intra-operative three-dimensional scans for navigation can improve the reliability, accuracy, and safety of pedicle screw placement, reducing the risk for reoperation and hospitalization due to implant-related complications. Further improvement may be achieved by adequate consideration of potential sources of errors.

Keywords: Pedicle screw, Intraoperative computed tomography, O-arm navigation, Screw malposition, Cortical perforation

1. Introduction

Safety remains the foremost concern during pedicle screw fixation, as violations can have catastrophic outcomes including nerve root injury and spinal cord injury.1 Because of the proximity to the spinal canal and surrounding vessels, misplacement of the pedicle screw can lead to disastrous complications, especially in the cervical and upper thoracic spine, where the morphometric variation of the pedicles and their proximity to vital structures make it difficult to place the pedicle screws accurately.2 Free-hand and fluoroscopy-assisted techniques have been associated with high rates of incorrect pedicle screw placement (range, 15–40%).3,4 The need for accurate and safe placement of screws has led to the adoption of image guidance systems to assist pedicle screw insertion. Such approaches include computed tomography (CT)-based navigation, two-dimensional (2D) fluoroscopy-based navigation, three-dimensional (3D) fluoroscopy-based navigation, and O-arm-assisted navigation.5 Among these, CT-based, 3D fluoroscopy-based, and O-arm assisted navigation can provide the surgeon with 3D visualization of the spine during the surgery.

CT-based navigation requires preoperative CT scans performed using a specific protocol, followed by transferring the obtained images to the navigational system for use during the surgery. After paired-point matching and anatomical registration for the operation, the preoperative anatomical information is used to assist pedicle screw insertion.6 However, since preoperative CT scans are typically obtained in the supine position, discrepancies between the planned and actual screw insertion position tend to occur due to different patient positioning and intersegmental shifts in the spine during the surgery, which typically employs prone positioning.7 On the other hand, O-arm assisted navigation and navigation based on 2D or 3D fluoroscopy rely on the information acquired during the operation and provide real-time intraoperative visualization of the spinal anatomy.8 In O-arm assisted navigation, intraoperative 3D images are quickly acquired using cone-beam CT technology, and transferred to a CT-like navigation system through a computerized image-guidance system.9,10 Intraoperative CT-guided navigation, which uses high-quality 3D images, has emerged as a reliable guidance system for improving the accuracy of pedicle screw placement in spinal surgery.7 However, non-negligible screw placement error rates persist.

In the present study, we aimed to estimate the rate of pedicle screw malpositioning associated with intraoperative CT-based navigation-assisted placement of pedicle screws, and to identify the probable cause for such errors. Such information will be helpful in designing strategies to prevent screw malpositioning when using spinal navigation.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients and study design

Following institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective analysis of the records of patients who underwent pedicle screw fixation at the level of the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spine using the O-arm (O-arm® Medtronic plc.; Surgical Technologies, Louisville, USA). Only patients managed between January 2010 and December 2017 by the senior author were included in this study. All surgical procedures were performed after obtaining informed consent from the patients. Data collected in this study included demographic details, indication for surgery, neurological findings before and after surgery, and intraoperative findings. The intraoperative CT images obtained after pedicle screw insertion were reviewed to determine the accuracy of pedicle screw placement.

2.2. Surgical protocol

Following induction of general anaesthesia, the patient was positioned in prone position on the Jackson table. Navigation-guided instruments were used for all steps of pedicle screw insertion (Fig. 1). Standard surgical exposure of the spine was performed at the vertebral level with pathology. Then, the reference array was mounted over the spinous process closest to the operative level (Fig. 2). The O-arm was then brought into the operating field and the sterile drapes were pulled down after closing the gantry. The O-arm was positioned at the vertebral level of interest. Anteroposterior and lateral x-rays were taken to confirm the vertebral level requiring surgery. Then, a 360° CT scan was conducted to acquire 3D images of the site of operation. The data set acquired was automatically transferred to the navigation station (StealthStation S7; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), followed by automatic anatomical registration.

Fig. 1.

Navigation-guided fixation system.

Fig. 2.

Intra-operative images illustrating reference array positioning and fixation to the spinous process. A) Open surgery. B) Minimally invasive surgery.

The next step was to determine the accuracy of the registered images by verifying them against bony landmarks in the operative field, which had been previously marked using the pins of the reference array. The screw entry point, trajectory, and length were planned using navigation. The entry point for the screw was created using a burr. Afterwards, a pedicle tract was created using a navigation-guided pedicle probe, followed by tapping using navigation-guided tap, and insertion of the pedicle screws with the help of a navigated screw driver (Fig. 3A). The position and trajectory of the screw was visualised on the monitor during screw insertion (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Intra-operative images illustrating navigated screw placement using the StealthStation system. 3A) Pedicle probing using a navigated Jamshidi needle. 3B) Screw insertion using the navigation system.

For minimally invasive surgeries, the procedure began with a short midline incision followed by docking of the reference array onto the spinous process (Fig. 2B). Using a planar probe, the pedicle entry points were marked on the skin. A navigated Jamshidi needle (CareFusion, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to create a pedicle tract, and a threaded k-wire was passed through the Jamshidi needle. Once the wire was pushed sufficiently into the pedicle, the needle was withdrawn. The next step was to tap and insert a cannulated pedicle screw over the k-wire using a navigated screw driver. The k-wire was removed after screw insertion. Another 3D scan was performed after all the screws were inserted, and images were analysed to detect any pedicle breach.

2.3. Analysis of screw malposition

Screw malposition was analysed based on the intraoperative CT scan obtained using the O-arm after insertion of the pedicle screws. The accuracy of screw placement was graded based on the Gertzbein classification. Screws that were fully contained in the pedicle were categorised as grade 0, breaches of ≤2 mm were classified as grade I, breaches of 2–4 mm were classified as grade II, and breaches of >4 mm were classified as grade III (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). While the main outcome was pedicle breach, we also looked for any cortex breach of the vertebral body.

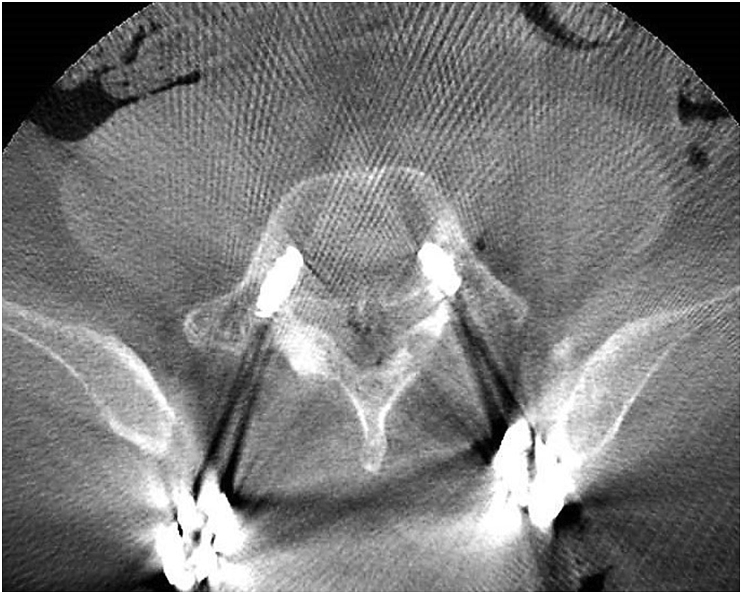

Fig. 4.

Intraoperative O-arm images showing the pedicle screw fully contained in the left pedicle of vertebra C4, with Gertzbein grade II breach on the right side.

Fig. 5.

Intraoperative O-arm images showing a Gertzbein grade I breach in the left pedicle of vertebra S1.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0. (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The incidence of breaches of grades I–III was calculated using a simple ratio method and was obtained for the overall sample, for each spine region, and for each vertebral level. The 95% confidence intervals were then calculated for the overall pedicle violation rates at each vertebral level. Linear regression analysis was used to compare the breach rates among the different vertebral levels.

3. Results

A total of 1152 pedicle screws were inserted in 219 patients during the study period. The mean age of the patients who underwent surgery was 58 years (range, 13–83 years). The patient demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Upon analysis of CT scans obtained intraoperatively, pedicle violations were noted for 47 of the 1152 screws inserted.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| Age | Value |

|---|---|

| Range | 13–83 years |

| Mean |

58 years |

|

Aetiology |

No. of patients (n = 219) |

| Tumour/Metastasis | 43 |

| Infection | 4 |

| Trauma | 28 |

| Degenerative |

144 |

|

Region wise distribution of pedicle screws |

No. of screws (n = 1152) |

| Cervical spine | 241 |

| Thoracic spine | 300 |

| Lumbar spine | 611 |

Of the 241 screws placed in the cervical spine (vertebral levels C2–C7), 17 had pedicle violation (overall breach rate, 7.05%; grade I breach, 3.73%, 9 screws; grade II breach, 3.32%, 8 screws), and all violations occurred as perforations of the lateral cortex. The highest rate of pedicle violation for screws inserted in the cervical spine was noted at vertebral level C7 (16.67%). The overall rate of pedicle violation for screws inserted in the cervical spine had a 95% confidence interval of 6.84–7.26% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of screws and pedicle violation rates in the cervical spine.

| Level | No. of screws | Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | Overall violation rate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | – |

| C3 | 47 | 3 (6.38%) | 1 (2.13%) | 0 | 4 (8.51%) | 7.35–9.60 |

| C4 | 54 | 2 (3.7%) | 1 (1.85%) | 0 | 3 (5.56%) | 4.73–6.33 |

| C5 | 52 | 2 (3.85%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0 | 5 (9.62%) | 8.51–10.67 |

| C6 | 44 | 1 (2.27%) | 2 (4.55%) | 0 | 3 (6.82%) | 5.70–7.85 |

| C7 |

12 |

1 (8.33%) |

1 (8.33%) |

0 |

2 (16.67%) |

10.58–21.69 |

| Total | 241 | 9 (3.73%) | 8 (3.32%) | 0 | 17 (7.05%) | 6.84–7.26 |

Pedicle violation was evaluated according to the Gertzbein classification: grade 0, screws fully contained in the pedicle; breaches of ≤2 mm, grade I; breach of 2–4 mm, grade II; and breach >4 mm, grade III. CI, confidence interval.

Of the 300 screws placed in the thoracic spine, 11 had pedicle violation (overall breach rate, 3.67%), with grade I breach for 6 screws (2%), grade II breach for 3 screws (1%), and grade III breach for 2 screws (0.67%). The overall rate of pedicle violation in the thoracic spine had a 95% confidence interval of 3.54–3.79% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of screws and pedicle violation rates in the thoracic spine.

| Level | Total | Grade 0 | Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | Overall violation rate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 28 | 27 (96.43%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.57%) | 1 (3.57%) | 2.27–4.87 |

| T2 | 40 | 39 (97.55) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (2.5%) | 1.73–3.27 |

| T3 | 18 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – |

| T4 | 12 | 12 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – |

| T5 | 22 | 21 (95.45%) | 1 (4.55%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.55%) | 2.69–6.40 |

| T6 | 30 | 27 (90%) | 2 (6.67%) | 1 (3.33%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | 8.04–11.96 |

| T7 | 26 | 25 (96.15%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.85%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.85%) | 2.40–5.30 |

| T8 | 22 | 22 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – |

| T9 | 19 | 17 (89.47%) | 1 (5.26%) | 1 (5.26%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10.53%) | 7.36–13.69 |

| T10 | 27 | 26 (96.30%) | 1 (3.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.70%) | 2.33–5.07 |

| T11 | 24 | 23 (95.83%) | 1 (4.17%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.17%) | 2.53–5.80 |

| T12 |

32 |

32 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

– |

| Total | 300 | 289 (96.33) | 6 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 2 (0.67%) | 11 (3.67%) | 3.54–3.79 |

Pedicle violation was evaluated according to the Gertzbein classification: grade 0, screws fully contained in the pedicle; breaches of ≤2 mm, grade I; breach of 2–4 mm, grade II; and breach >4 mm, grade III. CI, confidence interval.

Of the 611 screws placed in the lumbar spine, 22 had pedicle violation (overall breach rate, 3.6%), with grade I breach for 14 screws (2.29%) and grade II breach for 5 screws (0.82%). Perforation of the anterior cortex occurred for 2 screws (0.33%), both inserted at level S1, whereas perforation of the anterolateral cortex occurred for 1 screw (0.16%), which had been inserted at L5. The overall rate of pedicle violation in the lumbar spine had a 95% confidence interval of 3.54–3.66% (Table 4). No statistically significant difference was found regarding the breach rates across different vertebral levels, except for a minor difference in breach rates between the cervical and lumbar spine (p-value, 0.0329) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Distribution of screws and pedicle violation rates in the lumbar spine.

| Level | No. of screws | Grade 0 | Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | Anterior violation | Antero-lateral violation | Overall violation rate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 30 | 30 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.00–0.00 |

| L2 | 26 | 25 (96.15%) | 1 (3.85%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.85%) | 2.40–5.30 |

| L3 | 55 | 54 (98.18) | 1 (1.82%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.82%) | 1.34–2.29 |

| L4 | 186 | 173 (93.01%) | 11 (5.91%) | 2 (1.08%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (6.99%) | 6.72–7.26 |

| L5 | 228 | 223 (97.81%) | 1 (0.44%) | 3 (1.32%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.44%) | 5 (2.19%) | 2.07–2.32 |

| S1 |

86 |

84 (97.67%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (2.33%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (2.33%) |

1.98–2.67 |

| Total | 611 | 589 (96.4%) | 14 (2.29%) | 5 (0.82%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.33%) | 1 | 22 (3.6%) | 3.54–3.66 |

Pedicle violation was evaluated according to the Gertzbein classification: grade 0, screws fully contained in the pedicle; breaches of ≤2 mm, grade I; breach of 2–4 mm, grade II; and breach >4 mm, grade III. CI, confidence interval.

Table 5.

Summary of univariate logistic regression analysis.

| Comparision of level | Odds ratio (95% CI) | z statistic | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All breaches | |||

| Cervical vs Thoracic | 0.50 (0.23–1.0921) | 1.738 | 0.0822 |

| Cervical vs Lumbar | 0.49 (0.2566–0.9440) | 2.133 | 0.0329 |

| Thoracic vs Lumbar | 0.98 (0.4695–2.0513) | 0.050 | 0.9600 |

Statitisical significance p value < 0.05.

All screws with grade II or III breach were revised after analysing the intraoperative images (Fig. 6). None of the patients had complications associated with screw malposition. In one case, technical failure was judged to have been related to the intraoperative CT scan data. Specifically, an inaccuracy was noted upon verification following anatomical registration, which was due to loosening of the reference array clamp placed over the spinous process; the clamp was adjusted, and repeat scans were performed. No software failures were noted in this series.

Fig. 6.

Intraoperative O-arm image showing a malpositioned screw with subsequent revision.

Two patients who had undergone minimally invasive instrumentation of the lumbar spine developed superficial wound infection and delayed wound healing at the site of the incision made for docking the reference array; both patients were managed successfully with regular wound dressing. Another patient developed large swelling around the site of the incision made for docking the reference array over the T6 spinous process. On re-exploration, we noted an active bleeder in the paraspinal muscle tissue; the bleeder was coagulated, and haemostasis was achieved; the patient had an otherwise uneventful recovery.

4. Discussion

The placement of pedicle screws is a technically demanding procedure, especially at the level of the cervical and thoracic spine, where pedicles exhibit wide variation in anatomy and morphology.2,10 Furthermore, in order to safely place the screw, the surgeon needs to have spatial knowledge of the part of the spinal anatomy that is not exposed in the surgical field. For this reason, imaging-guided navigation is very helpful in spinal surgery requiring instrumentation.

Though fluoroscopic guidance is widely used worldwide for the placement of pedicle screws, this imaging modality does not provide high accuracy and moreover involves substantial radiation exposure because it requires repeated use intraoperatively. Furthermore, C-arm-acquired images may contain significant metal-related artefacts and do not provide good visibility of the lower cervical spine and upper thoracic spine. Previous studies on fluoroscopy-assisted placement of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar pedicle screws have reported highly variable pedicle breach rates (14.8%, 14.5–27.4%, and 5–41%, respectively).11, 12, 13, 14

O-arm navigation is widely recognized for its superior function in spinal surgery and its invaluable contribution to accurate placement of pedicle screws.8 In their meta-analysis focused on the accuracy of pedicle screw placement based on preoperative CT vs intraoperative data acquisition for spinal navigation, Liu et al. concluded that screw placement accuracy was higher for intraoperative than for preoperative CT-based navigation.5 Various studies have concluded that pedicle violations ≤2 mm are acceptable, safe, and not associated with adverse events.15 A review of the related literature suggests that different imaging-guided navigation modalities may be associated with different breach rates for different regions of the spine (Table 6).10,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 In the present study, we found that pedicle screw placement using O-arm-based 3D navigation results in very low rates of pedicle violation for all regions of the spine, which agrees with previous observations.

Table 6.

Literature review on the use of various imaging modalities as guidance for the insertion of pedicle screws.

| Authors | Year | Number of screws | Pedicle violation rate according to spinal region and navigation modality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oertel et al.16 | 2011 | 278 | Thoraco-lumbar: 3.2% (O-arm) |

| Tormenti et al.17 | 2010 | 375 | Thoraco-lumbar, on iCT: 1.2% Fluoroscopy: 5.2% |

| Rajasekaran et al.18 (RCT) | 2007 | 478 | Thoracic: Navigated 2%, Fluoroscopy 23% |

| Chiu et al.10 | 2017 | 1002 | Thoraco-lumbo-sacral, fluoroscopy: 11.2% |

| Mason et al.19 (systematic analysis) | 2014 | 3719 cervical 1223 thoracic 4368 lumbar |

Fluoroscopy, 8.3–50.3% (mean, 23.6%) 2D navigation, 5.0–26.3% (mean, 16.1%). 3D navigation. 0.0–19.1% (mean, 7.0%) |

| Van de Kelft et al.20 | 2012 | 1922 | Cervical, thoracic, lumbosacral: 2.5% (O-arm) |

| Dinesh et al.21 | 2012 | 261 | Thoracic: 2.7% (iCT) |

2D, two-dimensional; 3D, three-dimensional; iCT, immunofluorescent computed tomography; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

In our series, none of the malpositioned screws resulted in complications. It is interesting to observe that all four pedicle violations noted for screws placed in the cervical spine occurred as perforations of the lateral cortex. The risk of perforations of the lateral pedicle wall in the cervical spine remains a point of concern because the lateral pedicle wall is thinner and therefore less resistant.2 Additionally, the counter pressure from the nuchal muscles tends to direct the screw laterally during insertion, leading to lateral perforation of the pedicle wall, which carries a risk of laceration of the vertebral artery in the foramen transversarium. Similarly, screws inserted in the pedicles of lower lumbar vertebrae tend to have lateral or anterolateral violations due to counter pressure from the paraspinal muscles. Taken together, these findings suggest that, although intraoperative CT-guided navigation is more precise than navigation based on other imaging modalities, 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed.

To minimize the risk of breach and associated complications, it is important to plan and conduct the surgery in full consideration of the factors that may lead to screw malpositioning. Understanding the risk factors and potential sources of errors can help in the development and timely application of preventive measures. We further discuss the main mechanisms involved in cortical perforation by pedicle screws placed using intraoperative CT-based navigation.

Errors may occur during the anatomical registration process. It is important to verify the bony landmarks during each step of the surgery to confirm the accuracy of instrumentation.22,23 The reference array must be clamped well to the spinous process to prevent its loosening during surgery. Furthermore, care must be taken not to inadvertently knock the reference array off its position, as this deviation could lead to errors. The distance of the array from the site of instrumentation is also a factor that could lead to errors.22

In patients with spine instability or flexibility, intersegmental shifts can lead to changes in spine alignment during instrumentation, which can affect the accuracy of navigation.23 Furthermore, in patients with severe osteoporosis or obesity, the quality of the image obtained may not be ideal or the landmarks may be obscured, leading to navigational errors.

Malposition of the screw may occur with polyaxial screws that exhibit toggling movement at the interface with the screwdriver.17,22 Upon intraoperative investigation, we also found that such toggling movement can change the screw trajectory, thereby increasing the risk of perforation of the pedicle. During screw insertion, it is important to make sure that the screw is secured tightly to the screw driver, as well as to frequently check the screw trajectory. Such a check can be performed using the “hands off” test, wherein the surgeon removes the hand off the screwdriver and verifies the screw trajectory on the navigation system monitor.

Another important factor during navigated screw placement is the familiarity of the surgeon with the use of a navigation system. Navigation is in no way a substitute for the surgeon's knowledge, skill, and competence. There is a learning curve associated with the use of CT-guided navigation for safe and accurate placement of the pedicle screws. Hence, it is important for the surgeon to acquire the necessary training before using these navigation systems.8

Unplanned revision surgery after a spinal operation is associated with substantial medical care expenditures, as well as increased patient morbidity and mortality.24 In a systematic analysis of revision rates for misplaced pedicle screws in the thoracolumbar spine, Fichtner et al.25 concluded that, compared to free-hand fluoroscopy-guided placement, 3D fluoroscopy-based navigation-assisted pedicle screw placement is associated with significantly reduced rate of revision surgery for misplaced pedicle screws following posterior instrumentation of the thoracolumbar spine. In our series, we were able to identify grade II or III violations and revise these violations within the same operation, thereby avoiding the need for reoperation due to screw malposition and preventing potential complications associated with such malposition.

This study on O-arm-assisted navigation errors had a large sample size (1152 pedicle screws) and covered all regions of the spine (cervical, thoracic, and lumbar). However, the findings of this study should be seen considering the following limitations. There was no comparison with other methods, and no comparison with a control group. Therefore, a definite conclusion regarding the superiority of O-arm assisted navigation over other modalities cannot be drawn.

5. Conclusion

The use of O-arm-based intra-operative 3D scans for navigation can improve the accuracy and reliability of pedicle screw placement, thereby rendering it safer, which translates into reduced need for reoperation and hospitalization due to implant-related complications. Further improvement in the accuracy and reliability of this navigation modality can be achieved if one takes necessary precaution and keeps in mind the various sources of errors that may occur during navigated spine surgery.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

Dinesh Shree Kumar: Conceptualization, Project Administration, Writing – Review & Editing.

Nishanth Ampar: Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft.

Loo Wee Lim: Writing – Review & Editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- 1.Flynn J.M., Sakai D.S. Improving safety in spinal deformity surgery: advances in navigation and neurologic monitoring. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:131–137. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2360-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munusamy T., Thien A., Anthony M.G., Bakthavachalam R., Dinesh S.K. Computed tomographic morphometric analysis of cervical pedicles in a multi-ethnic Asian population and relevance to subaxial cervical pedicle screw fixation. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:120–126. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3526-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein J.N., Spratt K.F., Spengler D., Brick C., Reid S. Spinal pedicle fixation: reliability and validity of roentgenogram-based assessment and surgical factors on successful screw placement. Spine. 1988;13:1012–1018. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198809000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaccaro A.R., Rizzolo S.J., Balderston R.A. Placement of pedicle screws in the thoracic spine. Part II: an anatomical and radiographic assessment. J Bone Jt Surg. 1995;77:1200–1206. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199508000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu H., Chen W., Liu T., Meng B., Yang H. Accuracy of pedicle screw placement based on preoperative computed tomography versus intraoperative data set acquisition for spinal navigation system. J Orthop Surg. 2017;25 doi: 10.1177/2309499017718901. 2309499017718901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa F., Cardia A., Ortolina A., Fabio G., Zerbi A., Fornari M. Spinal navigation: standard preoperative versus intraoperative computed tomography data set acquisition for computer-guidance system: radiological and clinical study in 100 consecutive patients. Spine. 2011;36:2094–2098. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318201129d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holly L.T. Image-guided spinal surgery. Int J Med Robot. 2006;2:7–15. doi: 10.1002/rcs.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivkin M.A., Yocom S.S. Thoracolumbar instrumentation with CT-guided navigation (O-arm) in 270 consecutive patients: accuracy rates and lessons learned. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;36:E7. doi: 10.3171/2014.1.FOCUS13499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ammirati M., Salma A. Placement of thoracolumbar pedicle screws using O-arm-based navigation: technical note on controlling the operational accuracy of the navigation system. Neurosurg Rev. 2013;36:157–162. doi: 10.1007/s10143-012-0421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu C.K., Chan C.Y.W., Kwan M.K. The accuracy and safety of fluoroscopic-guided percutaneous pedicle screws in the thoracic and lumbosacral spine in the Asian population: a CT scan analysis of 1002 screws. J Orthop Surg. 2017;25 doi: 10.1177/2309499017713938. 2309499017713938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzey F.K., Emel E., Hakan Seyithanoglu M. Accuracy of pedicle screw placement for upper and middle thoracic pathologies without coronal plane spinal deformity using conventional methods. J Spinal Discord Tech. 2006;19:436–441. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200608000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishikawa Y., Kanemura T., Yoshida G. Intraoperative, full-rotation, three-dimensional image (O-arm)-based navigation system for cervical pedicle screw insertion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;15:472–478. doi: 10.3171/2011.6.SPINE10809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rampersaud Y.R., Simon D.A., Foley K.T. Accuracy requirements for image-guided spinal pedicle screw placement. Spine. 2001;26:352–359. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holly L.T., Foley K.T. Three-dimensional fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous thoracolumbar pedicle screw placement. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:324–329. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.99.3.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gertzbein S.D., Robbins S.E. Accuracy of pedicular screw placement in vivo. Spine. 1990;15:11–14. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oertel M.F., Hobart J., Stein M., Schreiber V., Scharbrodt W. Clinical and methodological precision of spinal navigation assisted by 3D intraoperative O-arm radiographic imaging. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14:532–536. doi: 10.3171/2010.10.SPINE091032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tormenti M.J., Kostov D.B., Gardner P.A., Kanter A.S., Spiro R.M., Okonkwo D.O. Intraoperative computed tomography image-guided navigation for posterior thoracolumbar spinal instrumentation in spinal deformity surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E11. doi: 10.3171/2010.1.FOCUS09275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajasekaran S., Vidyadhara S., Ramesh P., Shetty A.P. Randomized clinical study to compare the accuracy of navigated and non-navigated thoracic pedicle screws in deformity correction surgeries. Spine. 2007;32:E56–E64. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000252094.64857.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason A., Paulsen R., Babuska J.M. The accuracy of pedicle screw placement using intraoperative image guidance systems. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20:196–203. doi: 10.3171/2013.11.SPINE13413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van de Kelft E., Costa F., Van der Planken D., Schils F. A prospective multicenter registry on the accuracy of pedicle screw placement in the thoracic, lumbar, and sacral levels with the use of the O-arm imaging system and StealthStation navigation. Spine. 2012;37:E1580–E1587. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318271b1fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinesh S.K., Tiruchelvarayan R., Ng I. A prospective study on the use of intraoperative computed tomography (iCT) for image-guided placement of thoracic pedicle screws. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26:838–844. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.690917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathew J.E., Mok K., Goulet B. Pedicle violation and navigational errors in pedicle screw insertion using the intraoperative O-arm: a preliminary report. Internet J Spine Surg. 2013;7:e88–e94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsp.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller C.A., Ledonio C.G., Hunt M.A., Siddiq F., Polly D.W., Jr. Reliability of the planned pedicle screw trajectory versus the actual pedicle screw trajectory using intra-operative 3D CT and image guidance. Internet J Spine Surg. 2016;10:38. doi: 10.14444/3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai T.-T., Lee S.-H., Niu C.-C., Lai P.-L., Chen L.-H., Chen W.-J. Unplanned revision spinal surgery within a week: a retrospective analysis of surgical causes. BMC Muscoskelet Disord. 2016;17:28. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-0891-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fichtner J., Hofmann N., Rienmüller A. Revision rate of misplaced pedicle screws of the thoracolumbar spine–comparison of three-dimensional fluoroscopy navigation with freehand placement: a systematic analysis and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e24–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]