Abstract

Purpose

To examine the effect of co-incubating spermatozoa with human follicular fluid (HFF) on the rate of sperm DNA fragmentation.

Methods

This prospective study used semen (n = 23) and HFF from oocyte donors (n = 23). Liquified semen was divided into four aliquots: (1) neat semen (NEAT), (2) seminal plasma removed and replaced with sperm media (HTF) containing 0% (FF0), (3) 20% (FF20), or (4) 50% (FF50) HFF. Sperm motility and DNA fragmentation (SDF) were assessed following 24 h of incubation at 37 °C. Pro-oxidant capacity of HFF and seminal plasma and the effect of HFF on seminal plasma DNase activity was assessed in a sub-sample of 10 ejaculates.

Results

Sperm motility was higher after 3 h of incubation in media that contained HFF compared to the NEAT sample or when sperm was diluted in media without HFF. r-SDF (increase of SDF per time unit) values after 24 h of incubation for NEAT, FF0, FF20 and FF50 were 0.91, 0.69, 0.25 and 0.36, respectively. While pro-oxidant capacity of seminal plasma samples showed large variation (mean: 94.6 colour units; SD 65.4), it was lower and more homogeneous in FF samples (mean: 29.9 colour units; SD: 6.3). Addition of HFF to seminal plasma appeared to inhibit DNase activity.

Conclusion

While differences exist in the pro-oxidant capacity of seminal plasma of patients, sperm DNA integrity was preserved with addition of HFF to sperm media, irrespective of the level of pro-oxidant capacity. DNase activity in the original seminal plasma was abolished after HFF co-incubation.

Keywords: Sperm DNA fragmentation, Follicular fluid, Oxidative stress, DNase activity

Introduction

Human follicular fluid (HFF) has its own unique biochemical composition that constitutes the microenvironment of the developing follicle [1]. It also serves as an important mediator between follicular cells and the well-protected oocyte, providing for the necessary growth and development of the oocyte prior to ovulation. The major biologicals of HFF include proteins, hormones and metabolites [2]. In addition, other compounds such as polysaccharides, nutrients, growth factors, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidants are also present [3].

At ovulation, the cumulus-oocyte complex is drawn into the fallopian tube together with HFF by means of the ciliated infundibulum, so that HFF is consequently present at the time of fertilization suggesting that it may also play an important role with regards to sperm physiology (capacitation) in preparation for acrosome reaction and fertilization [4]. It is for this reason that HFF has been used at different concentrations combined with semen extenders to explore changes in sperm behaviour (motility and chemotaxis). While various studies have examined the effect of HFF concentration on sperm motility [4–8], the effect of HFF on sperm DNA fragmentation is limited to only one study [9].

Sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF) is an important semen parameter that is increasingly attracting the attention of clinicians as evidence of its negative impact on reproductive outcome accumulates [10–12]. In addition, it is also becoming apparent that SDF is far from a static value, so that it is not typically sufficient to measure this parameter only once at the time of ejaculation. Rather, the assessment of SDF appears highly dependent on post-ejaculation conditions used in the in vitro preparation of the spermatozoa [13]. Consequently, the negative impact of iatrogenic sperm damage is another important factor that must be controlled to achieve the best possible sperm sample at the time of fertilization.

Usually, when the human ejaculate is diluted in a semen extender, dynamic assessment of SDF results in increasing values over 1 to 6 h of incubation [8, 14]. Sperm DNA fragmentation following incubation also appears to be either patient and/or environmentally dependent [15] with the most intense sperm DNA damage being associated with the increased presence of ROS [16, 17]. In addition, other effectors such as the presence of DNases in the ejaculate may also be considered as potential contributors to DNA damage if they are active [18].

With the aim of trying to provide clinicians with methodologies to ensure the best semen sample at the time of fertilization, our group has systematically conducted different experiments to understand how SDF can be prevented or reduced, prior to and after ejaculation [13, 19, 20]. Our experimental rationale has been based on the dynamic assessment of SDF in order to place less emphasis on sperm DNA fragmentation at ejaculation [13, 21] and more on what might be present at the time of fertilization. Given that seminal plasma contains both pro-oxidant capacity and DNase activity, the aim of the present investigation was to test if rate of sperm DNA fragmentation could be modified after ejaculation using HFF and whether the mechanism of HFF action could be explained by means of its capacity to modulate ROS or DNase activity.

Material and methods

Patient and semen collection

All patients provided written informed consent for the use of their semen and follicular fluid in this study (CEI Conserjeria de Salud: CP.MDS-16-CI 1169-16). Semen samples, collected by masturbation, were obtained from 23 patients. Patient criteria for inclusion in the study were ejaculates with a sperm concentration > 25 × 106 sperm mL−1 and with a linear sperm motility of > 25% as measured using a CASA system. All male patients had been diagnosed with non-severe male factor idiopathic infertility.

Sperm DNA fragmentation

SDF was assessed using Dyn-Halosperm® (HalotechDNA, Madrid, Spain) according to the specifications provided in the kit. Baseline values of SDF were obtained at each predefined observation time and the rate of SDF (r-SDF), defined as the SDF increase per hour, was calculated. SDF was determined by analysing 300 spermatozoa per sample, per treatment, at each time point.

Follicular fluids

Follicular stimulation was homogenous for all oocyte donors and was conducted using 150–200 IU of r-FSH (GONAL-F®, Merck Serono, Australia) and 75 IU of hMG (Menopur 75, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, West Drayton, United Kingdom). This treatment was followed by administration of recombinant gonadotropin (0.25 mg of Orgalutran®, Organon Ltd., Ireland). Ovulation was induced with 250 μg recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin (Ovitrelle, Merck, The Netherlands). HFF was obtained via aspiration from the first donor follicle (approximately 18 mm dia) from which an oocyte was recovered. Native HFF was centrifuged at 350g for 10 min and the supernatant separated from the pellet. Aspirated HFF was inactivated by incubation at 56 °C for 30 min.

Experimental design

Liquified ejaculates from 23 different patients were divided into four equal aliquots. The first aliquot was assessed for sperm motility and DNA fragmentation without removal of the seminal plasma (NEAT) and then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h; this aliquot was then sequentially sub-sampled at the time of liquefaction (T0), 3 h of incubation (T3) and 24 h of incubation (T24) to assess the proportion of sperm with fragmented DNA (SDF). The remaining three aliquots were also centrifuged to remove the seminal plasma and then immediately re-suspended with sperm media (HTF-Media: Quinn’s Advantage™ Medium with HEPES Sage, Denmark), HTF with no follicular fluid (FF0), HTF supplemented with 20% v/v follicular fluid (FF20) and HFT supplemented with 50% v/v follicular fluids (FF50); these aliquots were also, subsequently incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and sperm motility and SDF assessed at T0, T3 and T24.

Pro-oxidant and DNase capacity experiments

Pro-oxidant capacity and DNase activity were tested in 10 randomly selected semen samples from the total cohort of 23 samples. Ten HFF samples were also randomly selected and tested for pro-oxidant capacity and DNase activity. Pro-oxidant capacity of spermatozoa was assessed using a commercially available kit (Oxisperm®, HalotechDNA, Madrid, Spain). The test is based on a colorimetric reaction in the presence of the NitroBlue Tetrazolium (NBT). Substances with pro-oxidant activity transfer electrons to the NBT generating an insoluble molecule (formazan) that has a purple colour. The intensity of the colour was assessed using image analysis protocols (ImageJ; https://imagej.nih.gov). The effect of HFF on seminal plasma nuclease activity was examined by incubating 4 μL of seminal plasma with 4 μL of HFF or dH2O (as negative control of DNase activity in seminal plasma) with 0.5 μg of genomic DNA at 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation, reaction volume was increased up to 15 μL by adding dH2O and the mixture was then extracted using phenol. Finally, aqueous phases were electrophoresed in 1% agarose gels in 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris, 20 mM acetic acid, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.3) and stained with GelRed (Biogen, Madrid, Spain).

Statistical analysis

All data and graphic illustrations were produced using SPSS 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis) were used to compare mean values of sperm motility, SDF and pro-oxidant capacity. To determine the dynamic behaviour of SDF over time, survival curves using a Kaplan–Meier analysis were created. Data were reported as newly fragmented sperm DNA cells that were present following each incubation observation time. Survival curves were compared using a log-rank test. To normalize the data, the background SDF was subtracted from each sample observation time, thus producing a common starting survival value of 100%. The level of significance was set as P < 0.05 for all the cases.

Results

Sperm motility

The effect of HFF on sperm motility following 24 h of incubation at 37 °C is shown in Fig. 1. There was no significant difference in the motility of spermatozoa observed at T0 between the NEAT, FF0, FF20, and FF50 sperm samples (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 0.002; p = 1.000). While the motility of spermatozoa incubated in the NEAT sample (χ2 = 14.124; P = 0.000) and FF0 media (χ2 = 11.463; P = 0.001) declined after 3-h incubation (T0–T3), there was no such decline in the motility of spermatozoa incubated in either FF20 (χ2 = 2.205; P = 0.138) or FF50 (χ2 = 3.453; P = 0.063) over the same time period. By 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, sperm motility in all samples (controls and HFF treatments) had declined to less than 20% motile.

Fig. 1.

Box and whisker plot of sperm motility from 23 patients following 24-h incubation at 37 °C for four experimental treatments. NEAT-freshly ejaculated sample after 30 min of liquefaction; FF0-spermatozoa incubated with HTF media only after seminal plasma removal; FF20-spermatozoa incubated with HTF media after seminal plasma removal with addition of 20% v/v follicular fluid; FF50-spermatozoa incubated with HTF media after seminal plasma removal supplemented with 50% follicular fluid. Dots label outlier cases as represented in the SPSS program

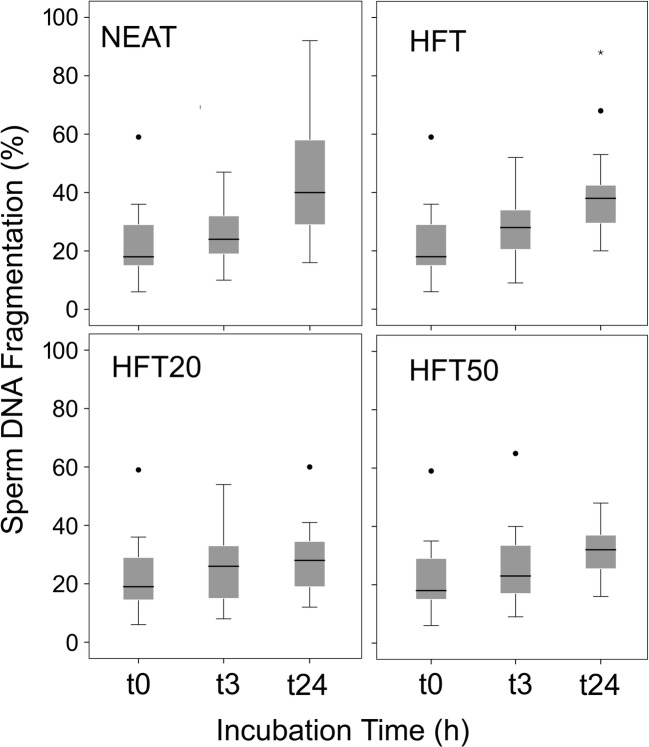

Sperm DNA fragmentation

The effect of HFF concentration on the proportion of sperm with fragmented DNA at each time point after 24-h incubation at 37 °C is shown in Fig. 2 The r-SDF (increasing values of SDF per time unit per hour) after 24 h of incubation for the NEAT, FF0, FF20 and FF50 were 0.91, 0.69, 0.25 and 0.36 (units of SDF per h), respectively. The increasing rates of SDF over time were compared by pairs using a Log Rank Mantel-Cox. The Kaplan-Meier survival comparison over the 24-h period showed significant differences when NEAT sperm samples were compared to FF0 (χ2 = 11.78; P = 0.001), when FF0 was compared to FF20 (χ2 = 52.38; P = 0.000) and when FF0 was compared to FF50 (χ2 = 34.85; P = 0.000). There was no difference in rSDF between spermatozoa diluted in FF20 and FF50 (χ2 = 1.85; P = 0.173).

Fig. 2.

Box and whisker plot of sperm DNA fragmentation from 23 patients following 24-h incubation at 37 °C for four experimental treatments. NEAT-freshly ejaculated sample after 30 min of liquefaction; FF0-spermatozoa incubated with HTF media only after seminal plasma removal; FF20-spermatozoa incubated with HTF media after seminal plasma removal with addition of 20% v/v follicular fluid; FF50-spermatozoa incubated with HTF media after seminal plasma removal supplemented with 50% follicular fluid. Dots and asterisk label outlier cases as represented in the SPSS program

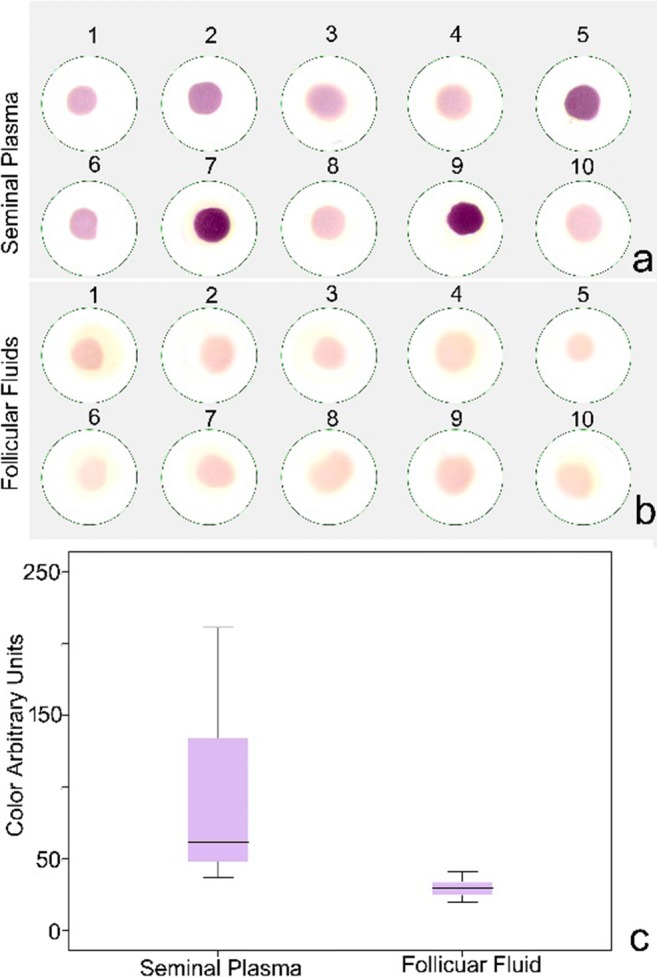

Pro-oxidant capacity in seminal plasma and follicular fluids

Pro-oxidant capacity of seminal plasma was examined in a subsample of 10 of the 23 male patients by means of an NBT assay and resulted in a large variation in colorimetric response (Fig. 3a, c; mean: 94.6 colour units; SD: 65.4). When the same procedure was applied to the 10 follicular fluid samples, the mean colorimetric response showed a statistically lower value (Mann-Whitney 1.5; p = 0.000) and presented with a more homogeneous distribution (Fig. 3b, c; mean: 29.9 colour units; SD: 6.3).

Fig. 3.

Nitroblue tetrazolium response in 10 samples of a seminal plasma and b follicular fluids. c Box and whisker plot representing data obtained using image analysis protocols. Colour arbitrary units presented by grey level values varying from 0 to 255 levels of grey

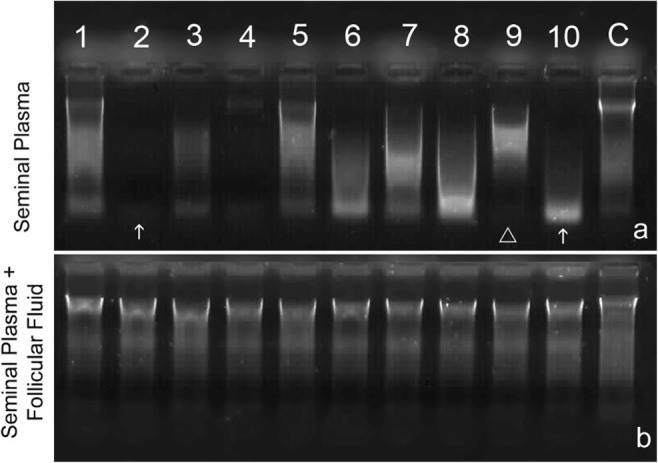

DNase activity

The seminal plasma of the same 10 individuals used to assess pro-oxidant capacity was also used to digest 0.5 μg of genomic DNA; the results of which are showed in Fig. 4a. There was a differential capacity to cleave the DNA depending on the sample. While lines 2 and 10 in Fig. 4a present high DNase activity, line 9 is the result of limited DNase activity. When these same seminal plasma samples were then mixed v/v with HFF, the capacity of this combined fluid to digest DNA was negated, irrespective of the HFF used in each experiment (see Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

DNase activity following digestion of 0.5 μg of DNA a DNase activity observed in the seminal plasma of 10 random individual males showing the large variability with respect to high (arrow) and low (arrow head) DNase activity and b DNase activity of the same seminal plasmas as a but mixed v/v with HFF showing the practical elimination of DNase activity

Discussion

While observations of short-term enhancement of sperm motility reported in our study and others [4, 5, 8] tend to confirm the importance of HFF to sperm storage and pre-fertilization events, such as capacitation, acrosome reaction, and chemotaxis, the primary aim of the current experiment was to explore the effect that HFF might exert on sperm DNA fragmentation and the possibility that a reduction in the rSDF may be associated with HFF blocking oxidative stress and/or DNase activity in the semen sample.

The impacts of co-incubating seminal plasma and spermatozoa after ejaculation are not well understood, since the effects appear to be species-dependent [22] and/or influenced by the conditions of sperm storage (e.g., cryopreservation versus chilling [23]). In humans, our group has demonstrated that co-incubation of sperm samples in seminal plasma after ejaculation increases iatrogenic sperm DNA damage and this effect is detectable after only 2-h incubation [24]; these observations indicate that ejaculates of patients or donors to be used for ART practice should have the seminal plasma removed soon after ejaculation–liquefaction, since this practice is likely to confer a significant benefit on reducing DNA fragmentation. The results presented in the current study further support this recommendation, as sperm DNA fragmentation after 24-h incubation was lower in those samples incubated in sperm media than in those incubated in their own seminal plasma. More importantly, we also report an additional novel finding with respect to the addition of FF on sperm DNA fragmentation such that spermatozoa in media supplemented with HFF showed a significant decrease in the rate of sperm DNA fragmentation, whereby the r-SDF declined from 0.69 in FF0 to 0.25 in FF20 samples, representing a reduction of approximately 2.8×. These results are consistent with those published by Bahmanpour et al. [9] who also observed an increase in the percentage of spermatozoa with normal histone and protamine after 24-h incubation with medium supplemented with 10% HFF.

Previously, we have highlighted the importance of iatrogenic damage when assessing sperm DNA fragmentation on reproductive outcome [13, 25]. This phenomenon is especially important in the era of ART when trying to evaluate spermatozoa under in vitro conditions that attempt to replicate the environment of the female reproductive tract [26, 27]. Animal models, such as the zebra-fish, where oocytes can be fertilized with sperm under controlled levels of SDF (i.e. time since activation in the external environment) in order to provide increasing values of this parameter, have confirmed the negative impact of iatrogenic damage on embryonic development [28]. Similarly, in a rabbit model, where the same females can be inseminated with sperm samples presenting with high and low rates of SDF, there was an association with respect to the presence of still born pups born to those inseminated with semen with low levels of sperm DNA fragmentation [29]. In the case of human ART, it is assumed that increasing levels of sperm DNA damage observed in the ejaculate will have a direct and negative impact on reproductive outcome [30, 31]. While this is indeed likely to be the case, the predictability of this reproductive outcome is likely to be dependent on the state of the sperm DNA molecule at the time of the actual sperm–oocyte interaction, than with the values of DNA damage observed immediately after ejaculation. For example, Dazel et al. [32] have reported a negative effect associated with a delay in fertilization, when semen was collected in one clinic and then subsequently transported to a different clinic for insemination. Thus, strategies, conducted to assure a more stable DNA molecule after ejaculation, are likely to insure a lower level of iatrogenic sperm DNA damage and thereby lead to an increase in reproductive outcome.

The question arises as to which molecules or molecular mechanisms are likely to be linked to HFF supplementation that is responsible for the apparent reduction or mitigation of DNA degradation? We postulate three main candidates for the observed phenomena: (1) removing seminal plasma may improve sperm quality by reducing the capacity for oxidative stress; (2) in a similar fashion, active enzymes such as nucleases present in the seminal plasma are also being removed when seminal plasma is removed; and (3) co-adjuvant factors present in the FF fluid (e.g. Ca++, Mg++, Cd++) may positively interact with the sperm or active enzymes, so as to prolong membrane stability and thereby indirectly prevent DNA damage. The use of HFF to improve fertilization success is applicable to ARTs such as IU, IVF or ICSI, all of which can benefit via the selection of sperm with stable DNA. However, until the specific molecules responsible for this sperm DNA behaviour can been identified, the clinical application of HFF as an adjuvant to standard semen extenders to reduce sperm DNA fragmentation after ejaculation will be limited to consenting couples.

The observed low potential of pro-oxidant capacity observed in HFF in this study may mean that HFF also has the capacity to mitigate oxidative stress and therefore sperm DNA damage in the ampulla of the oviduct. The microenvironment generated around the oocyte at the time of fertilization is known to alter sperm behaviour before fertilization and some studies indicate that oxidative stress unbalance may be one of the causative factors of female infertility [33, 34], although this reaction can be partially modulated by direct administration of antioxidants [35]. It could be the case that HFF swept into the oviduct post ovulation may help to reduce ROS damage, so that incubation and/or delivery of sperm supplemented with HFF may provide additional benefit to assisted reproductive technologies including intrauterine insemination, IVF and sperm prepared for selection in the ICSI procedure.

With respect to the ability of HFF to block DNase activity, our results are clear, but again, the molecules and mechanisms have yet to be identified. As the HFF used in this study was heated at 56 °C, a temperature at which typically inactivates the protein, the inhibitor effect of HFF may be associated with the heat stable component of the HFF. As the activity of nucleases depends on divalent cations such as Ca++ and Mg++, we might further speculate that the inhibitory effect of HFF could be due to the chelating capacity of some component molecule(s) but this hypothesis requires further testing.

Conclusion

The results presented in this prospective study confirm a clear benefit in supplementing sperm media with HFF in terms of enhancing sperm motility in the short-term and reducing iatrogenic sperm DNA integrity when spermatozoa were separated from the seminal plasma. Given the low level of pro-oxidant capacity found in HFF when compared to seminal plasma as revealed in this study, we propose that the adverse effects of ROS on SDF could potentially be mitigated by the addition of HFF in sperm preparation/storage media. Equally, we have also demonstrated a possible “blocking” ability of HFF with respect to DNase activity in seminal plasma that is also likely to promote DNA longevity.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fawcett DW. A textbook of histology. London: Taylor and Francis; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen X, Liu X, Zhu P, Zhang Y, Wang J, Wang Y, Wang W, Liu J, Li N, Liu F. Proteomic analysis ofhuman follicular fluid associated with successful in vitro fertilization. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2017;15:58. doi: 10.1186/s12958-017-0277-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambekar AS, Nirujogi RS, Srikanth SM, Chavan S, Kelkar DS, Hinduja I, et al. Proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid: A new perspective towards understanding folliculogenesis. J Proteome. 2013;87:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Getpook C, Wirotkarun S. Sperm motility stimulation and preservation with various concentrations of follicular fluid. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2007;24:425–428. doi: 10.1007/s10815-007-9145-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendoza C, Tesarik J. Effect of follicular fluid on sperm movement characteristics. Fertil Steril. 1990;54:1135–1139. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)54017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ralt D, Goldenberg M, Fetterolf P, Thompson D, Dor J, Mashiach S, et al. Sperm attraction to a follicular factor(s) correlates with human egg fertilizability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:2840–2844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villanueva-Diaz C, Arias-Martinez J, Bermejo-Martinez L, Vadillo-Ortega F. 1 progesterone induces human sperm chemotaxis. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)57982-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeon BG, Moon JS, Kim KC, Lee HJ, Choe SY, Rho GJ. Follicular fluid enhances sperm attraction and its motility in human. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2001;18:407–412. doi: 10.1023/A:1016674302652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bahmanpour S, Namavar MR, Talaei-Khozani T, Mazaheri Z. The effect of follicular fluid on sperm chromatin quality in comparison with conventional media. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:1840–1846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seli E, Gardner DK, Schoolcraft WB, Moffatt O, Sakkas D. Extent of nuclear DNA damage in ejaculated spermatozoa impacts on blastocyst development after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bungum M, Humaidan P, Axmon A, Spanò M, Bungum L, Erenpreiss J, et al. Sperm DNA integrity assessment in prediction of assisted reproduction technology outcome. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:174–179. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gosálvez J, López-Fernández C, Fernández JL, Esteves SC, Johnston SD. Unpacking the mysteries of sperm DNA fragmentation. Journal of Reproductive Biotechnology and Fertility. 2015;4:205891581559445. doi: 10.1177/2058915815594454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gosálvez J, López-Fernández C, Fernández JL, Gouraud A, Holt WV. Relationships between the dynamics of iatrogenic DNA damage and genomic design in mammalian spermatozoa from eleven species. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78:951–961. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sliwa L. Hyaluronic acid and chemoattractant substance from follicular fluid: in vitro effect of human sperm migration. Arch Androl. 1999;43:73–76. doi: 10.1080/014850199262751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wdowiak A, Bakalczuk S, Bakalczuk G. Decreased activity of superoxide dismutase in the seminal plasma of infertile men correlates with increased sperm deoxyribonucleic acid fragmentation during the first hours after sperm donation. Androl. 2015;3:748–755. doi: 10.1111/andr.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saleh RA, Agarwal A, Nada EA, El-Tonsy MH, Sharma RK, Meyer A, et al. Negative effects of increased sperm DNA damage in relation to seminal oxidative stress in men with idiopathic and male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1597–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright C, Milne S, Leeson H. Sperm DNA damage caused by oxidative stress: modifiable clinical, lifestyle and nutritional factors in male infertility. Reprod BioMed Online. 2014;28:684–703. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villani P, Eleuteri P, Grollino MG, Rescia M, Altavista P, Spanò M, et al. Sperm DNA fragmentation induced by DNAse I and hydrogen peroxide: an in vitro comparative study among different mammalian species. Reproduction. 2010;140:445–452. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gosálvez J, González-Martínez M, López-Fernández C, Fernández JL, Sánchez-Martin P. Shorter abstinence decreases sperm deoxyribonucleic acid fragmentation in ejaculate. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1083–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hebles M, Dorado M, Gallardo M, González-Martínez M, Sánchez-Martin P. Seminal quality in the first fraction of ejaculate. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2015;61:113–116. doi: 10.3109/19396368.2014.999390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ortiz I, Dorado J, Morrell J, Gosálvez J, Crespo F, Jimenez JM, et al. New approach to assess sperm DNA fragmentation dynamics: fine-tuning mathematical models. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2017;8:23. doi: 10.1186/s40104-017-0155-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrell JM, Rodriguez-Martinez H. Biomimetic techniques for improving sperm quality in animal breeding: a review. Open Androl J. 2009;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan C, Wu Y, Yang Q, Ye J. Effects of seminal plasma concentration on sperm motility and plasma and acrosome membrane integrity in chilled canine spermatozoa. Pol J Vet Sci. 2018;21:133–138. doi: 10.24425/119031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tvrdá E, Arroyo F, Gosálvez J. Dynamic assessment of human sperm DNA damage I: the effect of seminal plasma-sperm co-incubation after ejaculation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2018;50:1381–1388. doi: 10.1007/s11255-018-1915-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gosálvez J, Cortés-Gutiérrez EI, Nuñez R, Fernández JL, Caballero P, López-Fernández C, Holt WV. A dynamic assessment of sperm DNA fragmentation versus sperm viability in proven fertile human donors. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1915–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuura R, Takeuchi T, Yoshida A. Preparation and incubation conditions affect the DNA integrity of ejaculated human spermatozoa. Asian J Androl. 2010;12:753–759. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nabi A, Khalili MA, Halvaei I, Roodbari F. Prolonged incubation of processed human spermatozoa will increase DNA fragmentation. Andrologia. 2014;46:374–379. doi: 10.1111/and.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gosálvez J, López-Fernández C, Hermoso A, Fernández JL, Kjelland ME. Sperm DNA fragmentation in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) and its impact on fertility and embryo viability - implications for fisheries and aquaculture. Aquaculture. 2014;433:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.05.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston SD, López-Fernández C, Arroyo F, Gosálbez A, Cortés Gutiérrez E, Fernández JL, et al. Reduced sperm DNA longevity is associated with an increased incidence of still born; evidence from a multi-ovulating sequential artificial insemination animal model. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0754-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aitken RJ, De Iuliis GN, Mclachlan RI. Biological and clinical significance of DNA damage in the male germ line. Int J Androl. 2009;32:46–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2008.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan J, Taskin O, Albert A, Bedaiwy MA. Association between sperm DNA fragmentation and idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2019;38:951–960. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalzell LH, McVicar CM, McClure N, Lutton D, Lewis SE. Effects of short and long incubations on DNA fragmentation of testicular sperm. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1443–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agarwal A, Gupta S, Sharma RK. Role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta S, Ghulmiyyah J, Sharma R, Halabi J, Agarwal A. Power of proteomics in linking oxidative stress and female infertility. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:916212. doi: 10.1155/2014/916212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luddi A, Capaldo A, Focarelli R, Gori M, Morgante G, Piomboni P, de Leo V. Antioxidants reduce oxidative stress in follicular fluid of aged women undergoing IVF. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2016;14:57. doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0184-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]