Abstract

The Pandanus tectorius methanolic (PTM) and P. tectorius aqueous (PTA) extracts were investigated for their potential in vivo anti-inflammatory activity using carrageenan-induced rat paw edema. Parameters including paw thickness measurement, histopathological, and immunohistochemical cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 expression analyses were measured and analyzed. PTA at 500 mg/kg significantly reduced inflammation after induction of carrageenan (Carr), with mean paw thickness change of 0.110 ± 0.024 mm at sixth hour post-induction and histopathological mean inflammatory grade of 1.80 ± 0.20. The reduced immunohistochemical COX-2 expression using PTA at 500 mg/kg was determined with mean final 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) intensity of 63.70 ± 2.08. The profiling of metabolites by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) revealed presence of ethyl caffeate and dihydroconiferyl alcohol as putative secondary metabolites of PTA which were the major peaks and have been reported to possess anti-inflammatory activities. This research has provided scientific insights of utilizing P. tectorius as a potential anti-inflammatory agent containing secondary metabolites which may be pharmacologically relevant.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-2087-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pandanus tectorius, Cyclooxygenase, Inflammation, Immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Inflammation is a non-specific immune response of an organism for the protection and healing against the effects of harmful stimuli (Mehta et al. 2013). Chronic inflammation is linked to the leading causes of mortality in the Philippines (Leading Causes of Mortality 2013) and worldwide (The Top 10 Causes of Death 2018), including diseases of the vascular system, malignancies, chronic lower respiratory diseases, and diabetes mellitus.

One of the central inflammatory pathways is the arachidonic acid (AA) cascade which is mediated by cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX) (Joshi et al. 2016). COXs play essential roles in the formation of prostanoids, which include prostaglandins (PGs) and thromboxanes (TXs). Two major isoforms of COX, COX-1 and COX-2, facilitate the synthesis of basal and inflammatory prostanoids, respectively (Khan et al. 2016). Although synthetic COX inhibitors are commercially available, these drugs are associated to toxicities that could outweigh their benefits (Babby and Lall 2015). Hence, medicinal plants are being tapped as biologically active materials to combat inflammation.

The genus Pandanus (Pandanaceae) is comprised of approximately 700 species, mostly distributed in tropical and sub-tropical regions in the Pacific Islands, Australia, and the Malaysian Islands. Several Pandanus species are regarded as medicinal plants in traditional folk medicine. The presence of steroids, terpenoids, flavonoids, lignans, benzenoids, and alkaloids is elaborated in the phytochemical analyses on Pandanus species (Tan and Takayama 2019). P. tectorius is an important medicinal plant of the genus and grows abundantly in the Philippine coastal areas. Pharmacological studies revealed its anxiolytic (Bhatt and Bhatt 2016), anticoagulant (Omodamiro and Ikekamma 2016), antihyperlipidemic (Zhang et al. 2013a), and diuretic (Tan et al. 2014) properties. The leaves are also used in traditional medicine in the treatment of heartache, earache, arthritis, debility, giddiness, laxative, rheumatism, smallpox and spasms (Sanjeeva et al. 2011), while the root decoction is used to treat hemorrhoid (Wen et al. 2011). The fruits, male flowers and aerial roots are also employed to combat digestive and respiratory disorders (Omodamiro and Ikekamma 2016).

In our continuing interests on the phytochemical and pharmacological studies of the genus Pandanus (Tan and Takayama 2019), we herein describe the scientific basis on the folkloric claim on the use of P. tectorius extracts as an anti-inflammatory agent.

Materials and methods

Reagents and materials

Indomethacin and carrageenan were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Singapore). Normal saline solution (NSS) and 10% formalin solution were obtained from Mercury Drug (Philippines). Polyclonal COX-2 antibody was purchased from Abcam (UK). EnVision® + Dual Link System-Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) (3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) +) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) kit was obtained from DakoCytomation (USA). Colon cancer tissue slides were obtained from the Histopathology Section, Seamen’s Hospital (Manila, Philippines). The patient consent was carried out through the ethics review committee board of the hospital. The use of the human tissue sample was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The experimental protocols on the use of the human tissue sample were approved by the University of Santo Tomas (UST) Ethics Review Board.

Experimental animals

Sixty-three (63) male Sprague–Dawley rats (308–350 g) for in vivo anti-inflammatory determination were acquired from MOTS Animal House (Sta. Rosa, Laguna, Philippines). All experimental animals were acclimatized at the UST-Research Center for the Natural and Applied Sciences Animal House and acclimatized for 7 days prior to the conduct of the experiment at constant temperature (25 ± 2 °C), relative humidity (60 ± 4%), 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, and free access to food and water. All in vivo experiments performed were in accordance to the guidelines established by the UST Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) with an approval number of RC2017-920919 and were duly approved by the Bureau of Animal Industry with animal research permit AR-2017–376.

Plant material

Fresh, matured leaves of P. tectorius were collected in Barangay Sabang, Santa Cruz, Zambales, Philippines in May 2017. The leaves were washed of dirt and air-dried away from sunlight prior to extraction. The plant sample was authenticated at the Botany Division of the Philippine National Museum with control number 17-04-608. A voucher specimen was deposited at the UST Herbarium.

Preparation of plant extracts

Air-dried, ground P. tectorius leaves (2.68 kg) were subjected to MeOH extraction for 5 days (24 h each) for a total volume of 20 L in a percolator and filtered. The collected filtrates were concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain the crude MeOH extract (PTM, 354 g). The aqueous leaf extract of P. tectorius was obtained by crushing the fresh, matured leaves (2.02 kg), adding dist. H2O (8 L) and boiling for 15 min with constant stirring. The extract mixture was cooled to room temperature, macerated overnight, and was filtered. The collected filtrate was lyophilized yielding the aqueous extract (PTA, 78 g).

In vivo anti-inflammatory activity: carrageenan-induced rat paw edema

The in vivo anti-inflammatory determination was adopted from Lee et al. (2017) with modifications. The animals were randomly divided into seven experimental groups as follows.

Normal control (NSS-treated)—three rats

NSS + 0.1 mL of 1.0% (w/v) Carr—ten rats

Indomethacin at 10 mg/kg + Carr—ten rats

PTM at 250 mg/kg + Carr—ten rats

PTM at 500 mg/kg + Carr—ten rats

PTA at 250 mg/kg + Carr—ten rats

PTA at 500 mg/kg + Carr—ten rats

PTM, PTA, NSS, and indomethacin were administered through oral gavage to the respective animals 3 days prior to Carr induction (Katanić et al. 2016). On the 4th day, 1 h after oral administration of the test samples to the treatment groups, 0.1 mL of 1.0% (w/v) Carr was subcutaneously injected into the sub-plantar side of the left hind paw of the rats. Before (at time 0) and at hourly intervals for 6 h after carrageenan induction, the paw thickness was measured using digital micrometer series 293 IP65 level (Mitutoyo, USA). Prior to the actual paw thickness measurement, the rats in each of the major experimental groups were further divided into two sub-groups (n = 5 each), as initial and late sub-groups. Initial sub-groups consisted of rats that were hourly measured for paw thickness for 2 h after Carr induction and paws were dissected for future tests after the second hour of measurement. Paw thickness of rats designated at the late sub-groups was hourly measured from the baseline up to the sixth hour post-Carr administration, and paws were dissected for future analyses after the sixth hour of measurement. Change in paw thickness was measured using the formula:

where Ct is the left hind paw thickness (mm) at time t; and C0 is the left hind paw thickness (mm) before carrageenan injection.

Histopathological analysis

The prepared paw specimen slides were microscopically viewed at 400 × total magnification using EVOS XL Cell Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The degree of inflammation, which was estimated by means of leukocyte infiltration, edema, and congestion of local vasculature, was evaluated with a score from 0 to 5. The scores were defined as follows: 0—no inflammation; 1—mild inflammation; 2—mild/moderate inflammation; 3—moderate inflammation; 4—moderate/severe inflammation, and 5—severe inflammation (Catherine et al. 2015). Scoring was assessed by a licensed veterinarian who was masked on the treatment sub-groups.

Immunohistochemical analysis of COX-2

Immunohistochemical analysis was based on the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue slides were incubated in an oven at 60 °C for 1 h. Deparrafinization and rehydration were conducted using the following reagents at a certain period and frequency: xylene for 5 min twice, absolute EtOH (Merck) for 3 min twice, 95% EtOH (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 min twice, and dist. H2O for 1 min twice. Then, antigen retrieval operation through heat-induced epitope retrieval was done as follows: after pre-heating diluted target retrieval solution in the staining jar in water bath is set at 95–99 °C, the slides were incubated for 10 min, then cooled for 20 min at room temperature, and finally soaked in diluted wash buffer for 5 min. Excess buffer in the slides was wiped off and the staining procedure was conducted. For the staining, 100 µL of dual endogenous enzyme block solution was added and incubated for 5 min. Then, the primary antibody polyclonal COX-2 at 1:200 dilution was applied and incubated for 30 min. This was followed by the addition of the secondary antibody (labeled polymer-HRP) and incubated for 30 min. Following every step mentioned, sections were carefully washed with wash buffer and incubation was done using a humidity chamber. Slides were incubated again in a chromogen solution prepared with DAB chromogen diluted using DAB substrate buffer for 10 min. Sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin for 1 min, and microscope slides for analysis were mounted using an appropriate mounting medium. Representative rat paw tissues as tissue type control and no primary antibody control in which COX-2 primary antibody was removed in the staining procedure were included in the experiment. Positive tissue type control was also included using a colon cancer tissue specimen. Microscopic analysis and capturing of tissue slides were performed under 400 × total magnification.

Captured slides were then loaded on ImageJ software and color deconvolution was applied on all photomicrographs using the plug-in IHC profiler to obtain the DAB-stained photos (Varghese et al. 2014). The regions of interest were selected in each DAB-stained photo and the pixel intensity value was extracted. Final DAB intensity value was calculated by subtracting the obtained pixel intensity value analyzed by ImageJ software from 255, where 255 represents the maximum pixel intensity of an RGB photo (Nguyen et al. 2013).

Untargeted LC–MS metabolite profiling

Five milligrams of the plant extracts were dissolved in 2 mL of LC–MS grade MeOH and were filtered in 0.2 μm polytetrafluoroethylene syringe filters. The filtrates were loaded at an injection volume of 1 μL and 400 μL/min/run flow rate. UltraPerformance Liquid Chromatography Waters ACQUITY BEH HSST3 (2.1 mm × 50 mm, 1.8 μm) column set at 30 °C was used in the separation of metabolites, while the solvent reservoir consisted of 5% acetonitrile/water + 0.1% formic acid/water (v/v) solution and 95% acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid (v/v) solution. MS analysis was performed at positive ionization mode [M + H]+. The mass spectrometer operating parameters were set as follows: cone voltage, 40 V; capillary voltage, + 3.0 kV; source offset, 80 V; low collision energy, 6 V; cone gas flow, 100 L/h; source temperature, 120 °C; desolvation temperature, 400 °C; and source calibration delivery system, which consists of internal reference (leucine-enkephalin, m/z 556.2771 (ESI +). The putative compounds were identified based on retention time, accurate mass measurement data, elemental composition, and error (ppm) by library matching using the Waters MassLynx™ Mass Spectrometry Software and Traditional Chinese Medicine database.

Statistical analysis

All experimental data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were carried out using XLSTAT software version 2018.5.52345 and PAST (Paleontological Statistics) software version 3.14. Statistical significance was analyzed by paired T test for comparison of pre- and post-treatments, and one-way ANOVA (equal variances)/Welch F test (unequal variances) followed by Tukey’s pairwise post hoc tests. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Change in paw thickness

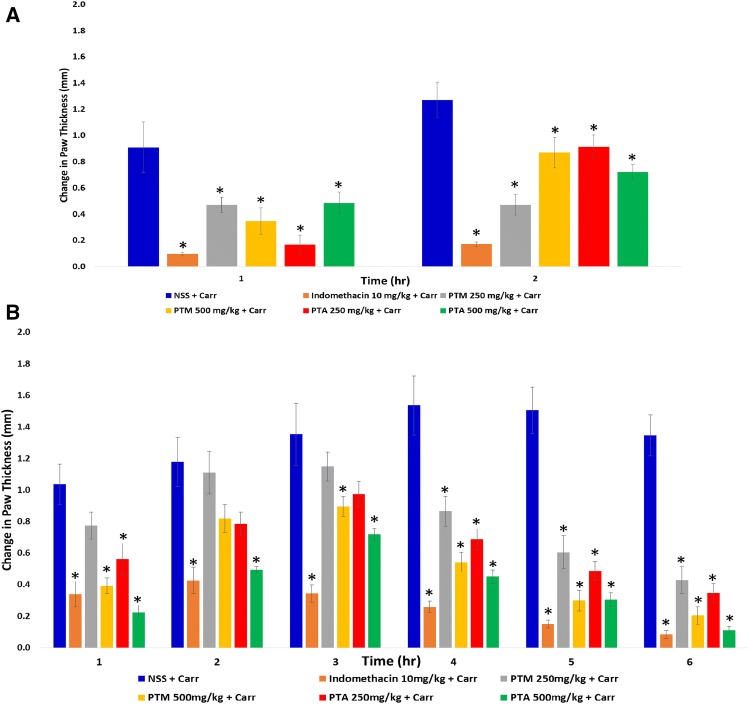

Indomethacin-treated initial sub-group had a significant difference with NSS + Carr initial sub-group at the first hour of measurement (p = 0.0001, Fig. 1a), where it provided the least extent in changes of paw thickness at 0.095 ± 0.014 mm. All extract-treated initial sub-groups had an increased paw thickness values after the second hour of measurement. Among them, PTM 250 mg/kg + Carr initial sub-group had the least increment in paw thickness from the first hour (0.469 ± 0.058 mm) up to second hour (0.471 ± 0.080 mm) of measurement. All other extract-treated initial sub-groups had an augmentation in the thickness, more than twice in comparison to the first hour of measurement.

Fig. 1.

Change in paw thickness of a initial and b late sub-groups in carrageenan-induced rat paw edema. Obtained values were represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the NSS + Carr initial sub-group

In Fig. 1b, NSS + Carr late sub-group exhibited the greatest change at the fourth hour of measurement at 1.535 ± 0.188 mm. Indomethacin-treated late sub-group was significantly different from the NSS + Carr late sub-group from third hour up to sixth hour of measurement by having the highest anti-inflammatory activity among the late sub-groups. All extract-treated late sub-groups had significant differences with NSS + Carr late sub-group from the fourth up to sixth hour of measurement. Notably, PTA 500 mg/kg + Carr late sub-group had its paw thickness values comparable to indomethacin + Carr late sub-group from the third up to sixth hour of measurement (third hour: p = 0.14; fourth hour: p = 0.72; fifth hour: p = 0.79; and sixth hour: p = 1.0). PTA 500 mg/kg + Carr late sub-group hourly reduced the paw thickness than PTA 250 mg/kg + Carr late sub-group from the third up to sixth hour of measurement, although there was no significant difference in the hourly effects between two doses given (third hour: p = 0.50; fourth hour: p = 0.51; fifth hour: p = 0.66; and sixth hour: p = 0.23). Representative photographs of the rats for the sixth hour post-induction are given in the Online Resource material.

Histopathological analysis

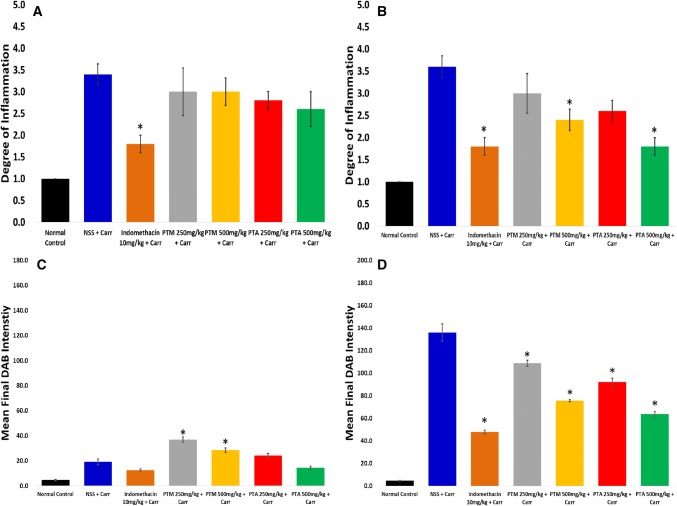

Figure 2 depicted that the NSS + Carr initial sub-group gave the highest extent of mean inflammatory score of 3.40 (moderate inflammation) at the end of second hour of measurement. Histopathological anti-inflammatory effects of all extract-treated initial sub-groups were considered as minimal in comparison to the NSS + Carr initial sub-group, all of which lowered the mean inflammatory score by only less than 1 from the inflammatory score from the NSS + Carr initial sub-group. For the initial sub-groups, histopathological photomicrographs revealed the presence of infiltrated leukocytes at the site of the carrageenan injection after second hour of measurement on paw thickness in the initial sub-groups (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 2.

Histopathological analysis of a initial and b late sub-groups in carrageenan-induced rat paw edema. Degree of inflammation was represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 5). Immunohistochemical COX-2 expression analysis of c initial and d late sub-groups in carrageenan-induced rat paw edema. Final DAB intensity was represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the NSS + Carr initial sub-group

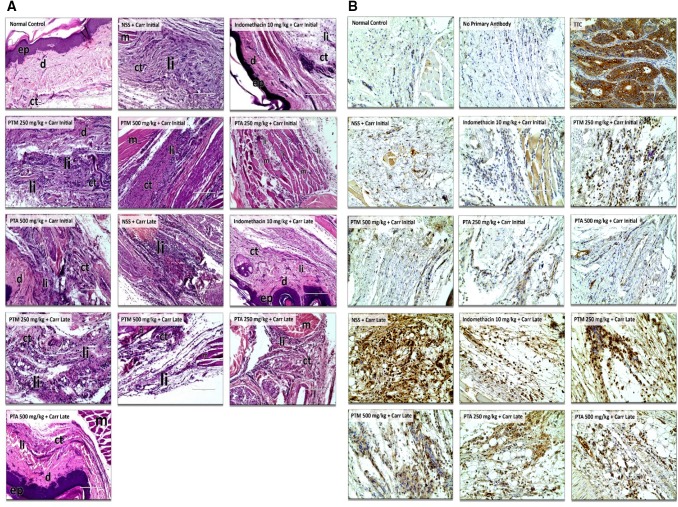

Fig. 3.

a Histopathological photomicrographs of paw tissues in normal control, initial and late sub-groups at 400 × total magnification. b Immunohistochemical photomicrographs of paw tissues in normal control, initial and late sub-groups at 400 × total magnification. ep epidermis, d dermis, ct connective tissues, li leukocyte infiltration, m muscle tissues, TTC tissue type control (colon cancer cells)

Histopathological analysis of the NSS + Carr-treated late sub-group showed a slight increase in the mean inflammatory score in comparison to the initial sub-group (Fig. 2b). Indomethacin-treated (p = 0.0008), PTM 500 mg/kg + Carr (p = 0.042), and PTA 500 mg/kg + Carr (p = 0.0008) late sub-groups had significant differences with the NSS + Carr late sub-group, which were assessed based on the presence of the infiltrated leukocytes and on the degree of edema in the paw tissues (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, PTA 500 mg/kg + Carr-treated late sub-group showed a lower inflammatory score, similar to indomethacin at 1.80 (p = 1.00).

Immunohistochemical analysis of COX-2

Minimal mean final DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine) intensity value was observed in the tissue controls without the primary antibody at 2.02 ± 0.10 as characterized by negligible brown stain coloration on the tissues (Fig. 3b—no primary antibody). On the contrary, a high average final DAB intensity value was seen in the colon cancer cell specimens at 178.01 ± 2.85 as designated by a high extent of brown stain coloration (Fig. 3b—TTC).

The NSS + Carr initial sub-group had a considerably lower final DAB intensity of 19.12 ± 2.21 (Fig. 2c), which was manifested by a lighter brown staining (Fig. 3b—NSS + Carr Initial). All extract-treated initial sub-groups provided a darker brown stain and exhibited a higher final DAB intensity value in comparison to NSS + Carr late sub-group, in which the PTM at both doses had significant differences with NSS + Carr initial sub-group (PTM 250 mg/kg + Carr: p < 0.0001; PTM 500 mg/kg + Carr: p = 0.012).

Immunohistochemical COX-2 expression analysis on late sub-groups (Fig. 2d) showed that all drug-treated sub-groups had significant differences with NSS + Carr late sub-groups. Indomethacin-treated sub-group revealed a significant reduction in the final DAB intensity in comparison to NSS + Carr sub-group (p < 0.0001), and evoked the effect of threefold better than the carrageenan control sub-group. PTA at 500 mg/kg + Carr late sub-group had the lowest mean final DAB intensity measurement of 63.70 ± 2.08 among all the extract-treated sub-groups and had a similar activity with the indomethacin-treated late sub-group (p = 0.041).

LC–MS metabolite profiling

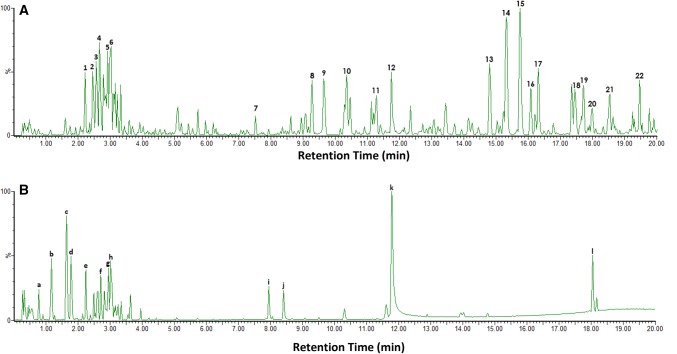

Figure 4 showed the LC chromatogram of the PTM extract where 22 putative compounds (Table 1) were detected, based on the observed pseudomolecular ion peaks at [M + H]+with high mass accuracy (ppm ≤ 5). Twelve putative compounds were identified from the LC chromatogram of the PTA extract (Fig. 4b) as summarized in Table 2

Fig. 4.

LC chromatogram of a Pandanus tectorius methanolic (PTM) and b Pandanus tectorius aqueous (PTA) extracts

Table 1.

LC–MS putative compounds from Pandanus tectorius methanolic (PTM) extract

| RT (min) | Observed m/z | Calculated m/z | Molecular formula | Error (ppm) | Putative identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.26 (1) | 332.0829 | 332.0818 | C15H15O7 | 3.31 | Malvidin |

| 2.95 (5) | 229.0797 | 229.0786 | C14H12O3 | 4.80 | Resveratrol |

| 3.04 (6) | 345.0891 | 345.0896 | C18H16O7 | − 1.45 | Cirsilineol |

| 5.57 (7) | 447.1208 | 447.1213 | C22H22O10 | − 1.12 | Swertisin |

| 9.28 (8) | 421.1766 | 421.1784 | C22H28O8 | − 4.27 | ( +)-Lyoniresinol |

| 9.65 (9) | 419.1612 | 419.1628 | C22H26O8 | 3.82 | ( +)-Syringaresinol |

| 11.28 (11) | 287.0481 | 287.0477 | C15H10O6 | 1.39 | Scutellarein |

| 11.76 (12) | 209.0737 | 209.0736 | C11H12O4 | 0.47 | Ethyl caffeate |

| 14.81 (13) | 385.1570 | 385.1573 | C22H24O6 | − 0.78 | Pandanusphenol A |

| 15.33 (14) | 177.0845 | 177.0837 | C11H12O2 | 4.52 | Ethyl cinnamate |

| 15.76 (15) | 217.1152 | 217.1150 | C14H16O2 | 0.92 | 3-Methyl-3-buten-1-yl cinnamate |

| 16.08 (16) | 285.2707 | 285.2715 | C18H36O2 | − 2.80 | Stearic acid |

| 16.32 (17) | 167.0993 | 167.0994 | C10H14O2 | − 0.60 | Viridine |

| 17.45 (18) | 109.0577 | 109.0575 | C7H8O | 1.83 | Benzyl alcohol |

| 17.72 (19) | 129.0836 | 129.0837 | C7H12O2 | − 0.77 | Isoprenyl acetate |

| 18.00 (20) | 343.0946 | 343.0951 | C15H18O9 | − 1.46 | Caffeic acid glucoside |

| 18.50 (21) | 287.0481 | 287.0477 | C15H10O6 | 1.39 | Luteolin |

| 19.47 (22) | 197.1454 | 197.1463 | C12H20O2 | − 4.57 | Geranyl acetate |

Table 2.

LC–MS putative compounds from Pandanus tectorius aqueous (PTA) extract

| RT (min) | Observed m/z | Calculated m/z | Molecular formula | Error (ppm) | Putative identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.79 (a) | 731.1727 | 731.1745 | C34H8O2 | − 2.46 | Isoorientin |

| 1.17 (b) | 149.0521 | 149.0524 | C9H8O2 | − 2.01 |

p-hydroxy cinnamaldehyde |

| 1.64 (c) | 183.0946 | 183.0943 | C10H14O3 | 1.64 | Dihydroconiferyl alcohol |

| 1.79 (d) | 361.0861 | 361.0845 | C18H14O3 | 4.43 | Centaureidin |

| 2.26 (e) | 332.0829 | 332.0818 | C17H15O7 | 3.31 | Malvidin |

| 2.95 (g) | 229.0797 | 229.0786 | C14H12O3 | 4.80 | Resveratrol |

| 3.03 (h) | 345.0891 | 345.0896 | C18H16O7 | − 1.45 | Cirsilineol |

| 7.96 (i) | 539.1697 | 539.1686 | C25H30O13 | 2.04 | Minecoside |

| 8.41 (j) | 287.0827 | 287.0841 | C16H14O5 | − 4.88 | Sakuranetin |

| 11.78 (k) | 209.0737 | 209.0736 | C11H12O4 | 0.47 | Ethyl caffeate |

| 18.05 (l) | 343.0946 | 343.0951 | C15H18O9 | − 1.46 | Caffeic acid glucoside |

Discussion

Inflammation is part of diverse biological responses of the body to omit adverse stimuli (Taofiq et al. 2015). It serves as a central feature in different chronic diseases, such as atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, obesity, COPD, arthritis and cancer (Gilroy et al. 2015). The safety of the crude leaf extracts of P. tectorius has been previously established (Bhatt and Bhatt 2016), hence, the efficacy on targeting prostanoid synthesis is an essential goal in searching for safer anti-inflammatory agents derived from natural sources.

The sub-groupings performed on the Carr-induced rat paw edema were patterned based on the pro-inflammatory effect of Carr. Carr produces a biphasic pro-inflammatory mechanism (Necas et al. 2013). The initial inflammation beginning phase is due to the release of inflammatory mediators at the affected sites, such as histamine, serotonin, and bradykinin. This phase occurs for 2 h after Carr administration. Expression of COX-2 and prostaglandins, particularly PGE2, is observed from 3 to 6 h post-Carr induction. At initial-phase inflammation, there was no promising anti-inflammatory activity by the extracts. The effects were short-lived due to reduced activity at the second hour of observation of the drug-treated sub-groups (Fig. 1a). The effect was also inconsistent relative to the dose given. This was evident when PTM at 250 mg/kg had a superior anti-inflammatory activity after 2 h than PTM at 500 mg/kg (Fig. 1a).

The Carr-induced late-phase inflammation is considerably more important than the initial phase, as it is an essential target in discovering for new anti-inflammatory agents. During late-phase inflammation, COX-2 expression is greatly increased (Necas et al. 2013; Katanić et al. 2016) and the peak of acute inflammatory effect by Carr occurs from 3 to 5 h after induction (Fehrenbacher et al. 2012). In the study, Carr exhibited its maximal pro-inflammatory effects from the fourth hour to fifth hour after induction (Fig. 1b—NSS + Carr). The histopathological inflammatory grade of NSS + Carr late sub-group was the highest (Fig. 2b), and its histopathological photomicrograph (Fig. 3a—NSS + Carr Late) showed the presence of numerous infiltrated leukocytes.

The PTA extract provided more significant results than PTM at late-phase inflammation from the induction of Carr based on change in paw thickness (Fig. 1b) and histopathological analysis (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, results of PTA at 500 mg/kg was comparable to indomethacin, suggesting its activity is attributed to targeting COX-2-mediated inflammation after Carr administration.

To further establish the in vivo COX-2 modulatory potentials of the PTM and PTA extracts, IHC was performed. COX-2 is being expressed at the positive chromogenic staining at the cellular cytoplasm (Grewal et. al. 2005). Calibration of the polyclonal COX-2 antibody (antigen affinity purified) was done using the no antibody control and the tissue type control (Fig. 3b). The no antibody control was the specimen used from the experimental animals but no COX-2 antibody was instilled. The tissue type control consisted of colon cancer cells, where COX-2 expression is expected to be identified (Wu and Sun 2015). In the no primary antibody control sub-group, significantly low mean final DAB intensity signifies negligible COX-2 expression, while high mean final DAB intensity in colon cancer cell specimen proves a higher extent of COX-2 expression. With these results, it was realized that the purchased COX-2 antibody was calibrated and was highly specific with the COX-2 antigen.

Low mean final DAB intensity values were observed in NSS + Carr initial sub-group, which was comparable to the PTA at 250 mg/kg and 500 mg/kg, and indomethacin, a known COX-2 inhibitor (Fig. 2c). These results signified the low extent of COX-2 antigen–antibody interactions during the initial phase of Carr inflammation, where COX-2 expression is not yet evident (Necas et al. 2013).

On late sub-groups, a significant high degree of COX-2 expression was observed with NSS + Carr late sub-group, based on mean final DAB intensity (Fig. 2d), which is coherent with the late-phase pro-inflammatory effect of Carr. Indomethacin-treated late sub-group also exhibited low mean final DAB intensity in comparison to NSS + Carr late sub-group, justifying its COX inhibitory activity. PTA was able to significantly modulate the COX-2 expression in comparison to NSS + Carr, having the most remarkable activity in PTA at 500 mg/kg + Carr late sub-group. These data on PTA late sub-groups were consistent with the results obtained from changes in paw thickness and histopathological analysis. These results imply that the anti-inflammatory action of the PTA extract at 500 mg/kg was observed at late-phase inflammation from the induction of carrageenan, and it mainly modulated COX-2 expression in vivo.

While phytochemical studies involving isolation and structure elucidation have been conducted on P. tectorius, this is the first report on the metabolite profiling of the methanolic and aqueous extracts. LC–MS untargeted metabolite profiling revealed the presence of different putative compounds both from the PTM and PTA extracts (Tables 1 and 2). It is noteworthy that several of these putative compounds were previously isolated from the different Pandanus species, including pandanusphenol A (Zhang et al. 2013b), dihydroconiferyl alcohol, naringenin, sakuranetin, and tangeretin (Zhang et al. 2012), geranyl acetate, isoprenyl acetate, 3-methyl-3-buten-1-yl cinnamate, and ethyl cinnamate (Vahirua-Lechat 1996), viridine, benzyl acetate, benzyl salicylate, and benzyl alcohol (Kusuma et al. 2012), cirsilineol and stearic acid (Venkatesh et al. 2012), ( +)-syringaresinol and p-hydroxycinnamaldehyde (Nguyen et al. 2016).

Studies also showed that secondary metabolites provide synergistic action in targeting multiple pathways through interaction between bioactive components present within the plant (Zhou et. al. 2016), although further studies are warranted to justify this claim (Yuan et. al. 2017). Anti-inflammatory mechanisms other than COX-2 inhibition and/or modulation were also identified for the putative compounds. The inhibition of NF-κB activation of malvidin and naringenin prevented the activation of inflammatory cascade, such as COX-mediated prostanoid formation (Tornatore et al. 2012). Targeting IL-1β reduced COX-2 expression, as shown by the action of p-hydroxycinnamaldehyde and luteolin (Taniura et al. 2008). Caffeic acid glucoside, which inhibited TNF-α, may also prevent COX-2 expression, since expression of these compounds are directly related (Alvares et. al. 2018). Furthermore, targeting iNOS resulted in the alteration of COX-2 pathway (Zhu et al. 2012). This could be possible through the linkage between the iNOS inhibitory activity of dihydroconiferyl alcohol, sakuranetin, tangeretin, caffeic acid glucoside, and luteolin and their potential COX-2 modulatory effects.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the scientific basis on the therapeutic potential of P. tectorius against inflammation utilizing in vivo COX-2 modulation. Untargeted LC–MS metabolite profiling revealed the presence of putatively identified compounds in the P. tectorius extracts with known anti-inflammatory activity, in which synergistic activities of the compounds might have contributed to the effect of the plant. Deeper studies on the anti-inflammatory aspect of P. tectorius, both chemically and pharmacologically, are hereby warranted to develop safer plant-based agents.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The ADB-Pascual Pharma Corp. is gratefully acknowledged for the LC–MS analysis. This research was funded National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grants awarded by the Korean government (MEST, No. 2017R1A2B4012636) and the Commission on Higher Education (Philippines).

Author contributions

CDM performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript; ALC and MAT conceptualized the study; ALC, MAT, SSAN corrected the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Ethical approval

All in vivo experiments performed were duly approved by the UST Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee with approval number RC2017-920919, and the Bureau of Animal Industry, Philippines with permit number AR-2017–376.The use of the human tissue sample was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of the hospital’s ethics review committee. The experimental protocols on the use of the human tissue sample were approved by the UST Ethics Review Board.

Contributor Information

Seong Soo A. An, Email: seong.an@gmail.com

Mario A. Tan, Email: matan@ust.edu.ph

References

- Álvares PR, de Arruda JAA, Oliveira Silva LV, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of cyclooxygenase-2 and tumor necrosis factor alpha in periapical lesions. J Endod. 2018;44:1783–1787. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babby J, Lall A. An update on the cardiovascular risks associated with NSAIDs. J Nurse Pract. 2015;11:1058–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.08.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt PR, Bhatt KP. Neurobehavioral activity of Pandanus tectorius Parkinson (Pandanaceae) leaf extract in various experimental models. J PharmaSciTech. 2016;5:16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Catherine A, Muthukumar SP, Halami PM. Anti-inflammatory potential of probiotic Lactobacillus spp. on carrageenan induced paw edema in Wistar rats. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;81:530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbacher JC, Vasko MR, Duarte DB. Models of inflammation: carrageenan- or complete freund’s adjuvant-induced edema and hypersensitivity in the rat. CurrProtocPharmacol. 2012;56:541–544. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0504s56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy D, Maeyer RD. New insights into the resolution of inflammation. Sem Immunol. 2015;27:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal S, Herbert SP, Ponnambalam S, Walker JH. Cytosolic phospholipase A2-α and cyclooxygenase-2 localize to intracellular membranes of EA.hy.926 endothelial cells that are distinct from the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus. FEBS J. 2005;272:1278–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi V, Venkatesha SH, Ramakrishnan C, et al. Celastrol modulates inflammation through inhibition of the catalytic activity of mediators of arachidonic acid pathway: secretory phospholipase A2 group IIA, 5-lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase-2. Pharmacol Res. 2016;113:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katanić J, Boroja T, Mihailović V, et al. In vitro and in vivo assessment of meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) as anti-inflammatory agent. J Ethnopharm. 2016;193:627–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MJ, Saraf S, Saraf S. Anti-inflammatory and associated analgesic activities of HPLC standardized alcoholic extract of known ayurvedic plant Schleichera oleosa. J Ethnopharm. 2016;197:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma R, Reddy VP, Bhaskar BN, et al. Phytochemical and pharmacological studies of Pandanus odoratissimus Linn. Int J Pharmacog Phytochem Res. 2012;2:171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Leading Causes of Mortality (2013) https://www.doh.gov.ph/Statistics/Leading-Causes-of-Mortality. Accessed 1 Dec 2019

- Lee SA, Moon SM, Choi YH, et al. Aqueous extract of Codium fragile suppressed inflammatory responses in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264.7 cells and carrageenan-induced rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;93:1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta JP, Parmar PH, Vadia SH, et al. In vitro antioxidant and in vivo anti-inflammatory activities of aerial parts of Cassia species. Arab J Chem. 2013;10:1654–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Necas J, Bartosikova L. Carrageenan: a review. Vet Med (Praha) 2013;58:187–205. doi: 10.17221/6758-VETMED. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D, Zhou T, Shu J, et al. Quantifying chromogen intensity in immunohistochemistry via reciprocal intensity. Protoc Exch. 2013;2:3. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TP, Le TD, Minh PN, et al. A new dihydrofurocoumarin from the fruits of Pandanus tectorius Parkinson ex Du Roi. Nat Prod Res. 2016;30:2389–2395. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2016.1188095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omodamiro O, Ikekamma C. In vitro study of antioxidant and anticoagulant activities of ethanol extract of Pandanus tectorius leaves. Int Blood Res Rev. 2016;5:1–11. doi: 10.9734/IBRR/2016/22231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjeeva KR, Padmalaxmi D, et al. Antioxidant activity of methanol extract of Pandanus fascicularis Lam. Pharmacologyonline. 2011;1:833–841. [Google Scholar]

- Tan Mario A., Takayama Hiromitsu. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology. 2019. Recent Progress in the Chemistry of Pandanus Alkaloids; pp. 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MA, Ebrada MT, Nonato MG. Diuretic activity of Pandanus tectorius (Pandanaceae) Der Pharma Chem. 2014;6:423–426. [Google Scholar]

- Taniura S, Kamitani H, Watanabe T, et al. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 expression by interleukin-1β in human glioma cell line, U87MG. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2008;48:500–505. doi: 10.2176/nmc.48.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taofiq O, Calhelha RC, Heleno S, et al. The contribution of phenolic acids to the anti- inflammatory activity of mushrooms: screening in phenolic extracts, individual parent molecules and synthesized glucuronated and methylated derivatives. Food Res Int. 2015;76:821–827. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The top 10 causes of death (2018) https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death. Accessed 01 Dec 2019.

- Tornatore L, Thotakura AK, Bennett J, et al. The nuclear factor kappa-B signaling pathway: integrating metabolism with inflammation. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahirua-Lechat I, Menut C, Roig B, et al. Isoprene related esters, significant components of Pandanus tectorius. Phytochem. 1996;43:1277–1279. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(96)00386-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese F, Bukhari AB, Malhotra R, et al. IHC profiler: an open source plug-in for the quantitative evaluation and automated scoring of immunohistochemistry images of human tissue samples. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e96801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh S, Kusuma R, Sateesh V, et al. Antidiabetic activity of Pandanus odoratissimus root extract. Indian J Pharm Educ. 2012;46:340–345. [Google Scholar]

- Wen B, Lampe JN, Roberts AG, et al. Identification of novel anti-inflammatory agents from ayurvedic medicine for prevention of chronic diseases: “reverse pharmacology” and “bedside to bench” Approach. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:1595–1653. doi: 10.2174/138945011798109464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Sun G. Expression of COX-2 and HER-2 in colorectal cancer and their correlation. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6206–6214. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i20.6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H, Ma Q, Cui H, et al. How can synergism of traditional medicines benefit from network pharmacology. Molecules. 2017;22:1135. doi: 10.3390/molecules22071135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Guo P, Sun G, et al. Phenolic compounds and flavonoids from the fruits of Pandanus tectorius Soland. J Med Plant Res. 2012;6:2622–2626. doi: 10.5897/JMPR11.240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wu C, Wu H, et al. Anti-hyperlipidemic effects and potential mechanisms of action of the caffeoylquinic acid-rich Pandanus tectorius fruit extract in hamsters fed a high fat-diet. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wu H, Wu C, et al. Pandanusphenol A and B: two new phenolic compounds from the fruits of Pandanus tectorius Soland. Rec Nat Prod. 2013;4:359–362. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Seto SW, Chang D, et al. Synergistic effects of chinese herbal medicine: a comprehensive review of methodology and current research. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:201. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Zhu M, Lance P. iNOS signaling interacts with COX-2 pathway in colonic fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:2116–2127. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.