Abstract

Purpose

To compare a single-step medium with a sequential medium on human blastocyst development rates, aneuploidy rates, and clinical outcomes.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of IVF cycles that used Sage advantage sequential medium (n = 347) and uninterrupted Sage 1-step medium (n = 519) from July 1, 2016, to December 31, 2017, in an academic fertility center. Main outcome measures are blastocyst formation rates per two-pronuclear (2PN) oocyte and aneuploidy rates per biopsy.

Results

Of all IVF cycles, single-step medium yielded higher blastocyst formation rate (51.7% vs 43.4%) but higher aneuploidy rate (54.0% vs 45.8%) compared with sequential medium. When stratified by maternal age, women under age 38 had no difference in blastocyst formation (52.2% vs 50.2%) but a higher aneuploidy rate (44.5% vs 36.4%) resulting in a lower number of euploid blastocysts per cycle (2.6 vs 3.3) when using single-step medium compared to sequential medium. In cycles used single-step medium, patients ≥ age 38 had higher blastocyst rate (48.0% vs 33.6%), but no difference in aneuploidy rate (68.8% vs 66.0%) or number of euploid embryos (0.8 vs 1.1). For patients reaching euploid embryo transfer, there was no difference in clinical pregnancy rates, miscarriage rates, or live birth rates between two culture media systems.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates an increase in aneuploidy in young women whose embryos were cultured in a single-step medium compared to sequential medium. This study highlights the importance of culture conditions on embryo ploidy and the need to stratify by patient age when examining the impact of culture conditions on overall cycle potential.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-019-01621-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Culture media, Embryo development, Aneuploidy, Infertility, Pregnancy

Background

The use of extended embryo culture to the blastocyst stage and preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) has enabled identification and selection of embryos with the best developmental potential and improved in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinical outcomes. While numerous types of commercially available human embryo culture media exist for human blastocyst culture, the impact of culture conditions on blastocyst development and aneuploidy formation is not well understood. Single-step culture media and sequential culture media are the two major systems used by many human IVF clinics. Sequential media use two media with different components aimed at mimicking the in vivo conditions: the first phase medium mimics the environment in the fallopian tubes to support human oocyte fertilization and early embryonic development, and the second phase medium mimics the environment in the uterus to better sustain embryo development to the blastocyst stage. In the case of single-step culture media, embryos are cultured in one media from zygote to blastocyst. Theoretical and practical advantages of using single-step media include reducing the possibility of stress to embryos associated with exposing them to a different medium and ambient conditions on the day 3 media change, reducing the cost and labor intensity, and lowering the chance for errors in the clinical IVF laboratory [1]. However, factors such as evaporation and associated osmolality and pH increases in single-step culture system could offset any advantage of reduced dish and embryo handling [2].

Whether single-step media culture is better than sequential media in improving the embryo development remains controversial. In an early randomized controlled trial with women as the randomization unit, Machlon reported no difference in both the blastulation rate and ongoing pregnancy rate through single-step embryo culture media comparing sequential media [3]. In other two randomized studies, no differences between the single-step and sequential media with regard to good-quality embryos [4], fertilization, implantation rates, and ongoing pregnancy [5]. Studies that randomized sibling oocytes and zygotes yielded contradictory results. While no difference was noted in the rates of blastocyst development and morphological grade of blastocysts among the two culture systems [6–10], some other studies reported higher blastocyst formation in single-step media compared with sequential media [11, 12], or vice versa [13]. A meta-analysis of RCTs showed a slight beneficial effect of the single-step media in yielding more blastocysts as compared to sequential media while no difference in clinical outcomes were observed [14]. Very few studies have been conducted to compare the aneuploidy rates between single-step and sequential culture media, although a growing body of literature suggests a possible link between conditions used in the clinical IVF laboratory and resulting embryo mitotic aneuploidy/mosaicism [15]. In a randomized controlled trial, Werner [13] reported a significantly higher usable euploidy rate per 2PN zygote with the sequential media, possibly due to a higher blastocyst rate with respect to the single-step media. Cimadomo et al. [16] reported a comparable euploidy rate per biopsied blastocyst with the single-step media than with the sequential one. However, maternal age was not stratified for data analysis in the above studies, and there was no conclusive evidence to support one system versus the other for the culture of embryos to day 5/6.

While maternal age is the strongest predictor of embryonic aneuploidy, the aneuploidy rates have been observed to vary between clinics and reference labs [17]. These variations have been seen in donors and cannot be explained by maternal age alone. It raises the question whether different culture systems among IVF laboratories contribute to the observed aneuploidy rate variations among clinics. The aim of this retrospective study was to compare blastocyst formation rates, aneuploidy rates, and clinical outcomes for embryos cultured in a single-step medium versus a sequential medium. Because aneuploidy rates and embryo arrest rates all increase significantly after age 38 [18, 19], data was stratified into two age groups (< 38 and ≥ 38) to avoid the confounding factor of maternal age. One year of follow-up of the related frozen embryo transfers (FET) was included to evaluate the clinical outcomes per transfer.

Materials and methods

A retrospective study was conducted comprising of conventional IVF/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles performed at a university-affiliated IVF center during the period of July 1, 2016, to December 31, 2017. It was our standard practice to provide sequential culture media (Sage advantage sequential medium, REF ART-1021, ART-1027, and ART-1029) to all IVF and ICSI embryos before December 2016; at that time, this practice was discontinued, and we provided single-step culture media (Sage 1-step medium, REF 67010010D) to all IVF/ICSI embryos. The conventional IVF/ICSI cycles were performed in the same clinic and embryology lab with the same clinical protocols, laboratory protocols, and contact materials. There was no change of embryology laboratory personnel. The only change was the change of culture media. Therefore, cycles from January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2017, are compared with a historical cohort from July 1, 2016, to December 31, 2016. Institutional review board approval was obtained for this retrospective cohort study, and the data were collected from a single electronic medical record system.

We included patients with at least one fertilized egg in the study to evaluate the influence of culture media on blastocyst development and ploidy. Use of oocyte donation or gestational carrier were excluded to avoid confounding variables. Patients who underwent conventional IVF or ICSI treatment, including all ages, all stimulation protocols, and all endometrial preparation protocols in the study period were included. The IVF cycles that underwent blastocyst biopsy on day 5 or 6 for PGT-A were further analyzed to assess the influence of culture media on aneuploidy. Decision of PGT-A was made by patients after they had consultation with a genetic counselor and physicians. Preimplantation genetic testing for known chromosomal translocations, single-gene disorders, cases that underwent fresh blastocyst transfer the day after biopsy or transferred two euploid embryos were excluded from the study to avoid confounding factors.

Oocyte retrieval occurred approximately 35 h after administration of hCG. Oocyte cumulus complexes were isolated from follicular aspirates and then held in equilibrated Sage single-step media with pre-supplemented 5 mg/ml human serum albumin or Sage sequential media with 10% serum protein substitute (Quinns Advantage™ SPS), in a 37 °C humidified 5% O2 and 6% CO2 for 2–4 h. Oocytes were then fertilized using either conventional insemination or ICSI. Approximately 18 h after insemination or ICSI, oocytes were examined for the presence of pronuclei. When Sage single-step medium was used, the zygotes were group cultured at 37 °C in separate 80 μl single microdrops (5–6 embryos per microdrop) under 13-ml Sage mineral oil in an atmosphere containing 5% O2 and 6% CO2 up to the blastocyst stage (days 5–6) without renewal of culture media. When Sage sequential medium was used, a change of culture media on day 3 was performed by transferring embryos to a new 80 μl drops of Sage sequential blastocyst medium in the same 5–6 embryo groups. The size and type of dishes were the same during both time periods and we used same 13 mL of SAGE Mineral Oil (ART-4008-5) in both sequential and single-step media. The culture temperature and gas concentrations in the incubators were monitored daily, and the pH of both culture media was confirmed to be 7.25–7.32. Both Sanyo MCO-5M humidified incubator and ESCO Miri benchtop incubator were used in the study period. All the blastocysts were graded on D5 or D6 according to their morphological quality based on the Gardner criteria [20]. The fertilization rate was calculated by dividing the number of 2 pronuclei zygotes obtained by the number of oocytes retrieved (conventional IVF) or the number of mature oocytes injected for ICSI. The blastocyst formation rate was analyzed based on the number of usable blastocysts that were available for biopsy or freezing per normally fertilized MII egg (2PN). Any blastocyst grade that was above 3BB was considered as high-grade blastocyst.

All PGT-A embryos were partially hatched on day 3 in the same microdrop of media. Blastocysts with a grade of 3CC and above at days 5/6 underwent trophectoderm biopsy. Embryos that did not reach blastocyst stage on day 5 were cultured in the same media until day 6 without a refreshing media change. All blastocysts were frozen by vitrification soon after biopsy. A standardized protocol was employed for biopsy as follows: embryos were placed in a droplet containing Quinn’s Advantage Medium with HEPES. Approximately 3–8 trophectoderm cells were withdrawn from each embryo and separated using the Hamilton Thorne LYKOS laser. Biopsied trophectoderm cells were placed in 0.2 mL PCR tubes containing 2 μL buffer solution that was provided by Igenomix Inc. After cell loading, the PCR tubes were immediately frozen at − 20 °C and kept in the freezer until transportation to the Igenomix testing center. The next-generation sequencing platform used in the current study was Ion GeneStudio™ S5 with the Ion Chef™ system (ThermoFisher Scientific) which allowed for an automated chip loading and ability to analyze up to 96 samples simultaneously in less than 24 h. The cell lysis, DNA amplification, and sequencing analysis were performed at Igenomix testing center based on manufacturer recommendations (https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LSG/manuals/MAN0016712_IonReproSeqPGS_S5_UG.pdf). Calling policy for “euploidy,” “whole chromosomal aneuploidy,” or “segmental aneuploidy” was not revised by the genetic testing lab during the duration of the study. Aneuploidy rates and incidence of whole chromosomal aneuploidy and segmental aneuploidy were calculated per number of biopsied blastocysts.

Vitrification and thawing of embryos were performed using Cryotech Vitrification Kit, device, and solutions. Only one euploid blastocyst was transferred in each frozen embryo transfer cycle. After warming and until transfer, the blastocyst was placed into the same media used for embryo culture but with 10% human serum albumin. Endometrial preparation and transfer procedure were performed as standard protocols in our center. A clinical pregnancy was defined as a serum quantitative hCG level > 5 mIU/ml and the presence of a gestational sac on transvaginal ultrasound at 6–7 weeks of gestation. A clinical miscarriage was defined as a loss of an intrauterine pregnancy after a gestational sac had been identified on ultrasound and between 6 and 20 weeks gestational age. Live births were defined as birth of a neonate at or beyond 24 weeks gestation and were documented by patient report. Clinical pregnancy rates and live birth rates were calculated per euploid embryo transfer. Miscarriage rates were calculated per pregnancy.

Statistical analysis

Independent t test or Pearson’s chi-square test were used for continuous or categorical variables, respectively. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated. Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

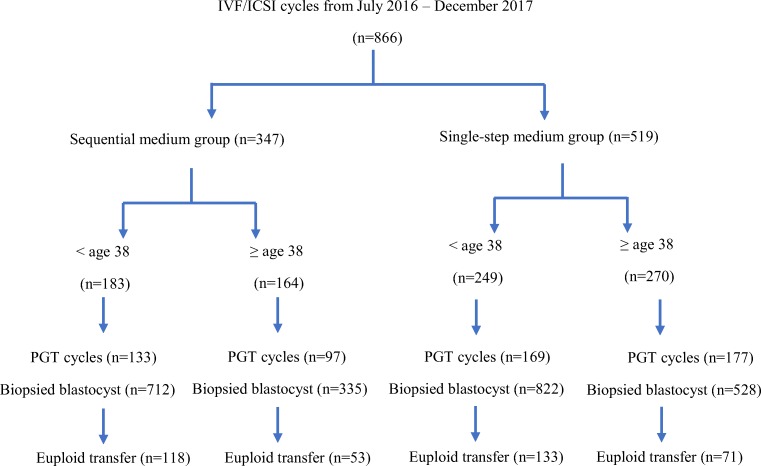

In a 1.5-year period (July 2016–Dec 2017), a total of 866 IVF cycles were performed with at least one egg fertilized. Of the 866 IVF cycles, 519 cycles used single-step culture medium while 347 cycles used sequential embryo culture medium. A total of 576 PGT-A cycles (2397 blastocysts) were eligible for aneuploidy analysis, including 346 cycles using single-step culture medium and 230 cycles using sequential embryo culture medium. Cycles underwent PGT-A were stratified into two age groups (Fig. 1). The distribution of main characteristics of the IVF cycles including prior reproductive history, causes of infertility, and stimulation protocols in two phases were not significantly different (Table 1). The proportion of ICSI was 61.2% in single-step media and 65.0% in sequential media, equally distributed between two culture media groups (p = 0.250). Majority of cycles (96.2%) were triggered with hCG with or without Lupron.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study comparing single-step versus sequential medium culture

Table 1.

Patient and IVF cycle characteristics

| Sequential medium (n = 347) | Single-step medium (n = 519) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.2 | 37.4 | 0.370 |

| Gravida (n ± SD) | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 0.524 |

| Number of prior miscarriages (n ± SD) | 1.0 ± 1.05 | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 0.473 |

| Infertility factors | 0.877 | ||

| Male factor | 32.2% | 28.0% | |

| DOR | 32.5% | 35.3% | |

| Other female factors | 15.0% | 15.9% | |

| Combined infertility | 20.3% | 20.8% | |

| IVF protocols | 0.172 | ||

| Antagonist | 88.6% | 83.3% | |

| Other protocol | 11.4% | 16.7% | |

| IVF cycles underwent PGT-A (%) | 63.4% | 66.7% | 0.980 |

Of all IVF cycles, no difference of fertilization rate was observed among two culture media, regardless of age. Significantly higher blastocyst formation rate per 2 PN embryo was observed in single-step medium (51.7%) than that in sequential medium (43.4%, RR = 1.1756, 95% CI 1.1080–1.2473; p = 0.001). When the data was categorized into different age groups, the higher blastocyst formation rate in single-step medium was only seen in older women who are age 38 and beyond (48.0% vs 33.6%, RR = 1.4290, 95% CI 1.2844–1.5897; p < 0.0001). The blastocyst formation rates of the two culture media in women younger than age 38 were similar (52.2% vs 50.2%, RR = 1.0402, 95% CI 0.9700–1.1155; p = 0.484). The high-grade blastocyst formation rate and the percentage of cycles that had no blastocysts available for biopsy or freezing were similar between two culture media in both age groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Fertilization rate and blastocyst formation rate in age-specific groups

| Sequential medium | Single-step medium | Relative risk | 95% confidence interval | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 38 (n) | 183 | 249 | |||

| Fertilization rate | 69.8% | 67.8% | 0.9707 | 0.9181–1.0264 | 0.527 |

| Blastocyst rate per 2PN | 50.2% | 52.2% | 1.0402 | 0.9700–1.1155 | 0.484 |

| High-grade blastocyst rate per 2PN | 44.1% | 40.2% | 0.9130 | 0.8285–1.0061 | 0.166 |

| No blastocyst formed cycle (n, %) | 23 (12.6%) | 34 (13.7%) | 1.0864 | 0.6632–1.7797 | 0.775 |

| Age ≥ 38 (n) | 164 | 270 | |||

| Fertilization rate | 70.3% | 65.1% | 0.9272 | 0.8584–1.0014 | 0.310 |

| Blastocyst rate per 2PN | 33.6% | 48.0% | 1.4290 | 1.2844–1.5897 | < 0.001 |

| High grade blastocyst rate per 2PN | 27.0% | 31.6% | 1.1677 | 0.9767–1.3961 | 0.134 |

| No blastocyst formed cycle (n, %) | 52 (31.7%) | 81 (30.0%) | 0.9462 | 0.7085–1.2635 | 0.748 |

A total of 1350 blastocysts in single-step medium and 1047 blastocysts in sequential medium were biopsied. While aneuploidy rates in both culture media (calculated upon biopsied blastocysts) increased with age as expected, higher aneuploidy rates were observed in the single-step medium than sequential medium (54.0% vs 45.8%, RR = 1.1779, 95% CI 1.0849–1.2788; p < 0.0001). When the data was analyzed by age-specific groups, the higher aneuploidy rate in single-step medium was only observed in young women < age 38 (44.5% vs 36.4%, RR = 1.2229, 95% CI 1.0811–1.3833; p = 0.002), which resulted in a smaller number of euploid blastocysts per retrieval cycle (2.6 vs 3.3, p = 0.009). In age group at 38 or beyond, aneuploidy rates per biopsy and number of euploid per cycle between the two culture systems were similar (68.8% vs 66.0%, RR = 1.0421, 95% CI 0.9467–1.1472; p = 0.707; 0.8 vs 1.1, p = 0.308). There was no significant difference in the percentage of cycles that had no euploids available for transfer between two culture media in both age groups (Table 3). Increasing time to embryo blastulation was associated with an increase in the prevalence of aneuploidy in each culture medium (Supplemental Table 1). The observed higher aneuploidy rate in single-step medium in age group < 38 was seen on both D5 (38.1% vs 33.7%) and D6 (47.7% vs 37.8%), although statistical significance was only observed in D6 embryos. No statistically significant difference of aneuploidy rates was observed on either D5 or D6 between two culture media in age group ≥ 38.

Table 3.

Aneuploidy in age-specific groups

| Sequential medium | Single-step medium | Relative risk | 95% confidence interval | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | ||||

| Age < 38 | |||||

| Number of PGT-A cycles | 133 | 169 | |||

| Number of biopsied blastocysts | 712 | 822 | |||

| Blastocysts per cycle (n) | 5.1 ± 3.7 | 5.0 ± 3.5 | 0.825 | ||

| Euploid blastocysts per cycle (n) | 3.3 ± 2.8 | 2.6 ± 2.2 | 0.009 | ||

| Aneuploidy | 259 (36.4%) | 366 (44.5%) | 1.2229 | 1.0811–1.3833 | 0.001 |

| Euploidy | 448 (62.9%) | 451 (54.9%) | 0.8720 | 0.8019–0.9482 | 0.003 |

| Cycle with no euploid blastocyst | 10 (5.5%) | 24 (9.6%) | 1.8888 | 0.9362–3.8106 | 0.147 |

| Age ≥ 38 | |||||

| Number of PGT-A cycles | 97 | 177 | |||

| Number of biopsied blastocysts | 335 | 528 | |||

| Blastocysts per cycle (n) | 3.2 ± 2.7 | 3.1 ± 2.8 | 0.580 | ||

| Euploid blastocysts per cycle (n) | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 0.308 | ||

| Aneuploidy | 221 (66.0%) | 363 (68.8%) | 1.0421 | 0.9467–1.1472 | 0.395 |

| Euploidy | 108 (32.2%) | 163 (30.9%) | 0.9761 | 0.7986–1.1929 | 0.761 |

| Cycle with no euploid blastocyst | 43 (26.2%) | 92 (34.1%) | 1.1967 | 0.9175–1.5609 | 0.089 |

Aneuploidy and euploidy rates were expressed per number of biopsied blastocysts

To investigate whether the culture media affected the incidence of segmental aneuploidies, which was suggested by previous studies originating during early mitoses following fertilization, we analyzed aneuploidy type among the two culture media (Supplemental Table 2). We observed that segmental errors occurred independently as well as alongside whole chromosome aneuploidies. Of all biopsied embryos, the incidence of segmental aneuploidy alone was 6.5% in single-step medium and 5.8% in sequential medium (RR = 1.1188, 95% CI 0.8154–1.5353, p = 0.4867). The incidence of combined segmental and whole chromosome aneuploidies was 3.6% in single-step medium and 2.3% in sequential medium (RR = 1.5188, 95% CI 0.9351–2.4670, p = 0.091). We did not observe any difference in aneuploidy incidence that involved segmental aneuploidy comparing single-step and sequential media in overall PGT-A cycles (10.0% vs 8.1%) or in any age specific group. The higher aneuploidy rate in single-step medium in patients < age 38 was due to increased incidence of whole chromosome aneuploidy. While the incidence of all aneuploidy and whole chromosome aneuploidy increased with maternal age as expected, the occurrence of segmental aneuploidy was observed to be trending down with advancing maternal age, although there is no statistical significance (9.0% vs 6.3% in age < 38 and ≥ 38 respectively in sequential medium, p = 0.133; 11.0% vs 8.9% in in age < 38 and ≥ 38 respectively in single-step medium, p = 0.224). Incidence of other abnormalities or non-diagnosis among two culture media in both age groups was similar.

The clinical outcomes of two culture media for patients who reached an euploid embryo transfer are shown in Table 4. In the patient group younger than 38, a clinical pregnancy rate of 62.4% and a live birth rate of 52.6% was achieved after single-step medium, which is not statistically different from those achieved after sequential medium (64.4% and 60.2%, p = 0.794 and 0.230 respectively). Similar clinical pregnancy rate (59.2% vs 50.9%, p = 0.465) and live birth rate (49.3% vs 43.4%, p = 0.515) were also observed between two culture media in age group at 38 or beyond. There was no statistical difference in miscarriage rates between two culture media in either age group. However, only a subset of the patients had returned for FET by the time that this study was performed.

Table 4.

Clinical pregnancy rate per euploid embryo transfer, miscarriage rate per pregnancy, and live birth rate per euploid embryo transfer in age-specific groups

| Euploid transfer cycles | Sequential medium | Single-step medium | Relative risk | 95% confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | ||||

| Age < 38 (n) | 118 | 133 | |||

| Clinical pregnancy | 76 (64.4%) | 83 (62.4%) | 1.0321 | 0.8551–1.2457 | 0.794 |

| Miscarriage | 5 (6.6%) | 13 (15.7%) | 0.4200 | 0.1571–1.1229 | 0.083 |

| Live birth rate | 71 (60.2%) | 70 (52.6%) | 0.8747 | 0.7033–1.0879 | 0.230 |

| Age ≥ 38 (n) | 53 | 71 | |||

| Clinical pregnancy | 27 (50.9%) | 42 (59.2%) | 0.8612 | 0.6208–1.1947 | 0.465 |

| Miscarriage | 4 (14.8%) | 7 (16.7%) | 0.8889 | 0.2873–2.7499 | 1.000 |

| Live birth rate | 23 (43.4%) | 35 (49.3%) | 1.1359 | 0.7710–1.6737 | 0.515 |

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that embryos cultured in a single-step medium had a significantly higher aneuploidy rate and lower number of euploid embryos when compared to the more traditional sequential medium in women younger than age 38. In women at age 38 and beyond, there was no difference in aneuploidy rates between two culture media despite an observed higher blastocyst formation rate in the single-step medium.

Recent data suggests that the frequency of chromosome abnormalities can be influenced by iatrogenic factors associated with ovarian stimulation regimens and different embryo culture conditions in the IVF lab. A retrospective analysis of 13282 trophectoderm biopsies from blastocysts that were generated from 1645 oocyte donor cycles in 42 different IVF clinics showed that blastocyst euploidy rates per individual cycles ranged from 0 to 100% and were not normally distributed. Euploidy rate was dependent on donor age, but was also affected by the referring IVF clinic [17]. In another large study where types of chromosome abnormalities were examined, incidence of segmental chromosome errors, unlike whole chromosome aneuploidy, was not influenced by female age. Instead, the incidence of segmental chromosome errors increased markedly from oocytes (10%) to blastocyst stage (15.6%), indicating a combination of sperm derived and post-zygotic partial abnormalities [21].

In our study, the main characteristics of the IVF cycles were similar between two culture media including the age, infertility factors, and ovarian stimulation. The IVF cycles in the study period were performed in the same clinic with the same embryology lab setting, lab protocols, and supplies except the change of culture media. Therefore, we were able to use the two cohorts to assess the impact of culture media on aneuploidy formation. We calculated aneuploidy rates in age-specific groups to avoid the confounding factor of maternal age. To avoid the impact of different blastocyst rates in two culture media, we calculated aneuploidy rate per biopsied blastocyst instead of the aneuploidy rate per 2PN zygote. Interestingly, we observed a significantly higher aneuploidy rate in single-step medium in patients younger than age 38. Given that meiotic errors occur before zygote formation and is age-related, in an age-specific group, any difference in aneuploidy rates between two culture systems would be assumed to reflect the proportional difference in the mitotic error rate. Thus, we analyzed aneuploidy type to see if the culture media altered the incidence of segmental aneuploidies, which was suggested by prior studies that the majority originated from mitotic errors after fertilization [22]. We observed an overall incidence of segmental aneuploidy as 10.0% in single-step medium and 8.1% in sequential medium that involved segmental alone and combined segmental and whole chromosome. These rates were similar to the reported occurrence rates of segmental aneuploidies at the blastocyst stage [21, 23]. We did not observe a significant difference of segmental aneuploidy incidence between the two different culture media in the young or older patients, and the incidence was not related to advancing maternal age.

Segmental aneuploidy is caused by DNA double stranded breaks, which can be induced by various endogenous and/or exogenous factors. Peak incidence of segmental aneuploidy was observed at the cleavage stage of embryos followed by decreased incidence at the blastocyst stage, which could be contributed by factors that relate to oocyte competence or possible influence of suboptimal oocyte/embryo culture systems on chromosome integrity [21]. No difference in the rate of segmental aneuploidy between two culture media in our study suggests that the single-step medium works the same as the sequential medium in terms of inducing replicative and/or other stresses which can ultimately cause double stranded DNA breaks and segmental aneuploidy. A recent commentary has discussed the possible link between the IVF laboratory culture conditions and embryo mosaicism [15]. Status of embryo mosaicism in this study was not available in genetic reports until 2018 and we were not able to compare prevalence of mosaicism in the two culture media due to incompleteness of data.

One reason why single-step medium resulted in higher aneuploidy in younger patients is potentially related to the relationship of embryo cytogenetic composition, metabolism, and adaption to in vitro culture. In a study that investigated 188 fresh and cryopreserved human embryos, the amino acid Asparagine, glycine, and valine turnover was significantly different between uniformly genetically normal and uniformly abnormal embryos on days 2–3 of culture [24]. In another study that applied Ramen spectra and principal component analysis, significant difference in metabolic footprints that were associated with small RNAs and lipids in culture media were observed among euploid and aneuploid embryos [25]. The small RNAs that were secreted into the culture media can play essential roles in signaling, regulation, and development of the embryo [26, 27]. Age-related mitochondria DNA dosage in the oocyte cytoplasm might further affect the embryo’s capability of adaption to the environment. The observed higher aneuploidy rate in young patients in single-step media in our study suggests that changes in gene copy number in aneuploid embryos might lead to altered media components in early cleavage stage that will subsequently impact the blastocyst formation. In addition, formulation difference between the two media might lead to different pH value, osmolality, and build-up of harmful by-products [2] which can potentially impact embryo development although we adjusted the CO2 to use both media in the same pH range. Different protein resources used in two culture media in this study were reported to generate different amounts of ammonia [22, 23], and SPS may have other components that could potentially impact embryo development. Therefore, euploid embryos derived from young patients are somehow less able to adjust well in a single-step medium leading to less euploid embryos reaching the blastocyst stage.

In our study, higher blastocyst formation rates were observed in women at age 38 and beyond. Earlier studies comparing single-step media and sequential media generated conflicting results in terms of blastocyst development and formation. It is possible that embryos derived from older patients are more sensitive and easier to be impacted by culture environment than embryos that are derived from younger patients. Keeping embryos in the same culture media for 5 days might give less biochemical and adaptive stress to the embryos from older patients. Single-step culture media also exposes embryos to a large spectrum of amino acids before day 3 [28]. Amino acid turnover has been shown to be related to blastocyst formation [29]. Embryos derived from older patients may have different metabolic requirements than embryos derived from younger patients, and they could adapt better in single-step media which resulted in higher blastocyst formation. However, the higher blastocyst rate did not translate into a higher number of high-grade blastocysts or a greater number of euploid blastocysts in this age specific group. It is important to note that day 6 blastocysts had a higher likelihood of aneuploidy as compared with day 5 blasotcysts in both culture media, which is consistent with previous findings and suggested that altered genetic component of aneuploid embryos may impact the rate of embryo development resulting in slower blastulation [30, 31].

We were not able to calculate cumulative pregnancy rate because only 30.1% euploid embryos were transferred by the time of our data analysis. In our study, no difference in clinical pregnancy rate per blastocyst transferred, or live birth rate, or miscarriage rate of two culture media in both age groups suggests that once a euploid blastocyst was of sufficient quality to be transferred, sustained clinical ongoing pregnancy rates were equivalent for single-step and sequential media. This is consistent with previous studies and is reassuring.

To our best knowledge, this study is the first one that analyzed the impact of culture media in age-specific groups. However, due to the non-randomized nature of our study, we are not able to exclude the possibility of non-equivalent of meiotic errors among two culture systems, which could potentially result in the observed difference in aneuploidy rates. Different protein sources used in two culture media might also contribute to the different outcomes that we observed, although unlikely. Here, we tested only one among the several commercially available media per each culture approach. Although single-step media formulations are based on the same principles of development, they may differ widely in the concentration of components and as such our results may not be generalizable to other commercially available formulations. Further studies are warranted to clarify the relationship between culture media components and its impact on embryo cytogenetic composition and subsequent impact on embryo development. A rigorous study design to randomize oocytes after completion of meiosis and compare two culture approaches with consideration of different age patient population is needed before we conclude which culture approach is superior to the other. Studies using different PGT-A platform is further needed as well to verify the impact of culture media to aneuploidy incidence. Although our study had the above limitations, the observation of higher aneuploidy rate by using single-step embryo culture in younger patients suggested that the frequency of blastocysts chromosome abnormalities might be influenced by embryo culture conditions in the IVF laboratory, and the patient age needs to be stratified when examining the impact of culture conditions on overall cycle potential.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 20 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staffs at Stanford IVF center for their clinical support of the study.

Authors’ roles

J.D. and Q.Z. were involved with study design, execution, and statistical analysis. J.D. wrote the manuscript. C.C. and R.K. coordinated data collection and statistical analysis. R.L. contributed interpretation of the data and edit of the manuscript. B.B. devised, supervised the study and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided critical feedback and discussion.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Both Cengiz Cinnioglu and Refik Kayali disclosed that they are employees of Igenomix Inc. All other authors do not have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

The work was done in Stanford Medicine Fertility and Reproductive Health Services.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Machtinger R, Racowsky C. Chapter 12: Culture systems: single step. In: Smith G, editor. Embryo culture: methods and protocols, methods in molecular biology: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Swain JE. Controversies in ART: considerations and risks for uninterrupted embryo culture. Reprod BioMed Online. 2019;39(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macklon NS, Pieters MH, Hassan MA, Jeucken PH, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC. A prospective randomized comparison of sequential versus monoculture systems for in-vitro human blastocyst development. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(10):2700–2705. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paternot G, Debrock S, D'Hooghe TM, Spiessens C. Early embryo development in a sequential versus single medium: a randomized study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:83. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campo R, Binda MM, Van Kerkhoven G, Frederickx V, Serneels A, Roziers P, et al. Critical reappraisal of embryo quality as a predictive parameter for pregnancy outcome: a pilot study. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2010;2(4):289–295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciray HN, Aksoy T, Goktas C, Ozturk B, Bahceci M. Time-lapse evaluation of human embryo development in single versus sequential culture media--a sibling oocyte study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(9):891–900. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9818-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed ML, Hamic A, Thompson DJ, Caperton CL. Continuous uninterrupted single medium culture without medium renewal versus sequential media culture: a sibling embryo study. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(5):1783–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Summers MC, Bird S, Mirzai FM, Thornhill A, Biggers JD. Human preimplantation embryo development in vitro: a morphological assessment of sibling zygotes cultured in a single medium or in sequential media. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2013;16(4):278–285. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2013.806823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardarson T, Bungum M, Conaghan J, Meintjes M, Chantilis SJ, Molnar L, et al. Noninferiority, randomized, controlled trial comparing embryo development using media developed for sequential or undisturbed culture in a time-lapse setup. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(6):1452-9.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basile N, Morbeck D, García-Velasco J, Bronet F, Meseguer M. Type of culture media does not affect embryo kinetics: a time-lapse analysis of sibling oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(3):634–641. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sfontouris IA, Kolibianakis EM, Lainas GT, Petsas GK, Tarlatzis BC, Lainas TG. Blastocyst development in a single medium compared to sequential media: a prospective study with sibling oocytes. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(9):1312–1318. doi: 10.1177/1933719116687653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sepúlveda S, Garcia J, Arriaga E, Diaz J, Noriega-Portella L, Noriega-Hoces L. In vitro development and pregnancy outcomes for human embryos cultured in either a single medium or in a sequential media system. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(5):1765–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werner MD, Hong KH, Franasiak JM, Forman EJ, Reda CV, Molinaro TA, et al. Sequential versus Monophasic Media Impact Trial (SuMMIT): a paired randomized controlled trial comparing a sequential media system to a monophasic medium. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(5):1215–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sfontouris IA, Martins WP, Nastri CO, Viana IG, Navarro PA, Raine-Fenning N, et al. Blastocyst culture using single versus sequential media in clinical IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33(10):1261–1272. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0774-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swain Jason E. Controversies in ART: can the IVF laboratory influence preimplantation embryo aneuploidy? Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2019;39(4):599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cimadomo D, Scarica C, Maggiulli R, Orlando G, Soscia D, Albricci L, et al. Continuous embryo culture elicits higher blastulation but similar cumulative delivery rates than sequential: a large prospective study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(7):1329–1338. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1195-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munné S, Alikani M, Ribustello L, Colls P, Martínez-Ortiz PA, McCulloh DH, et al. Euploidy rates in donor egg cycles significantly differ between fertility centers. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(4):743–749. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franasiak JM, Forman EJ, Hong KH, Werner MD, Upham KM, Treff NR, et al. The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 15,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):656–63.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas MR, Sparks AE, Ryan GL, Van Voorhis BJ. Clinical predictors of human blastocyst formation and pregnancy after extended embryo culture and transfer. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardner DK, Lane M, Stevens J, Schlenker T, Schoolcraft WB. Blastocyst score affects implantation and pregnancy outcome: towards a single blastocyst transfer. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(6):1155–1158. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babariya D, Fragouli E, Alfarawati S, Spath K, Wells D. The incidence and origin of segmental aneuploidy in human oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(12):2549–2560. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vera-Rodríguez M, Michel CE, Mercader A, Bladon AJ, Rodrigo L, Kokocinski F, et al. Distribution patterns of segmental aneuploidies in human blastocysts identified by next-generation sequencing. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(4):1047-55.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munné S, Chen S, Colls P, Garrisi J, Zheng X, Cekleniak N, et al. Maternal age, morphology, development and chromosome abnormalities in over 6000 cleavage-stage embryos. Reprod BioMed Online. 2007;14(5):628–634. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Picton HM, Elder K, Houghton FD, Hawkhead JA, Rutherford AJ, Hogg JE, et al. Association between amino acid turnover and chromosome aneuploidy during human preimplantation embryo development in vitro. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16(8):557–569. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang B, Gao Y, Xu J, Song Y, Xuan L. Shi T, et al. Fertil Steril: Raman profiling of embryo culture medium to identify aneuploid and euploid embryos; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kropp J, Salih SM, Khatib H. Expression of microRNAs in bovine and human pre-implantation embryo culture media. Front Genet. 2014;5:91. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suh N, Blelloch R. Small RNAs in early mammalian development: from gametes to gastrulation. Development. 2011;138(9):1653–1661. doi: 10.1242/dev.056234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Machtinger R, Racowsky C. Culture systems: single step. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;912:199–209. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-971-6_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brison DR, Houghton FD, Falconer D, Roberts SA, Hawkhead J, Humpherson PG, et al. Identification of viable embryos in IVF by non-invasive measurement of amino acid turnover. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(10):2319–2324. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaing A, Kroener LL, Tassin R, Li M, Liu L, Buyalos R, et al. Earlier day of blastocyst development is predictive of embryonic euploidy across all ages: essential data for physician decision-making and counseling patients. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(1):119–125. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-1038-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiegs AW, Sun L, Patounakis G, Scott RT. Worth the wait? Day 7 blastocysts have lower euploidy rates but similar sustained implantation rates as Day 5 and Day 6 blastocysts. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(9):1632–1639. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 20 kb)