Abstract

The present study aimed to improve the potency of inactivated Rift Valley Fever Virus (RVFV) vaccine using chitosan (CS) or chitosan nanoparticles (CNP) as adjuvants. Chitosan nanoparticles were prepared by ionic gelation method. Rift Valley Fever Virus (RVFV) inactivated antigen was loaded on CS and CNP to form two vaccine formulations, RVFV-chitosan nanoparticles based vaccine (RVFV-CNP) and RVFV chitosan based vaccine (RVFV-CS). Five groups of mice were used in this study, each group was injected with one of the following: phosphate buffer saline (group1 G1), RVFV-CNP (G2), (RVF-CS) (G3), RVFV-Alum based vaccine (RVFV-Alum) (G4) and adjuvant free RVFV inactivated antigen (RVFV-Ag) (G5). The immunization was performed twice with 2 weeks interval. The results showed that, RVFV-CNP vaccine enhanced strongly the phagocytic activity of peritoneal macrophage (PM), neutralization antibodies titer against RVFV and IgG values against RVFV nucleoprotein than other vaccine formulations did. In addition, the RVFV-CNP and RVF-CS vaccines upregulate the gene expression of IL-2, IFN-γ (which promote cell mediated immunity) and IL-4 (which promote humeral immunity), while RVFV-Alum vaccine upregulate the gene expression of IL-4 only. These findings indicated that CS and CNP were comparable to the alum as adjuvant in efficacy but superior to it in inducing cell-mediated immune response and might be a candidate adjuvant for inactivated RVFV vaccine.

Keywords: Chitosan, Nanoparticles, Rift Valley Fever, Vaccine

Introduction

Rift Valley Fever is an arthropod-borne viral disease affecting various classes of mammals including man (Gubler et al. 2002). The main vectors are mosquitoes of the genera, Aedes and Culex species that have a wide global distribution (Kenawy et al. 2018). RVFV is a member of the genus phlebo-virus, order Bunyavirales and belongs to family Phlebo-virus. It is an enveloped virus with a diameter of 90–110 nm (Ellis et al. 1988). RVFV was first isolated in 1930. RVF has proven to be capable of emerging in new areas or reappearing after long periods of dormancy. More than outbreaks have been recorded in Egypt (1977, 1993 and 2003) (Himeidan et al. 2016).In ruminants, RVFV causes massive abortion and high mortality among young animals (Coetzer 1982).

Successful vaccine depends on the use of adjuvants (Gupta et al. 2011), which boost the potency and longevity of specific immune responses to antigens with minimal toxicity without having any specific antigenic effect on their own (Wack and Rappuoli 2005). The aluminum hydroxide gel (alum) adjuvant has been successfully used in millions of humans as the principle adjuvant in clinical vaccines since 1932 (Marrack et al. 2009). However, alum-based adjuvant induce severe local tissue irritation, long duration of the inflammatory reaction at the injection site, strong T helper cell 2 (Th2) responses (Confavreux et al. 2001; Averhoff et al. 1998) and does not induce the cytokines interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) which are involved in cell-mediated immune responses [T helper cell 1(Th1) type response] (Ulanova, et al. 2001). Therefore, there is an urgent requirement for the development of alternative adjuvants, capable of boosting (Th1) type responses without unacceptable toxicity (Office International Des Epizooties (OIE) (2008)).

Chitosan, 2-amino-2-deoxy-b-d-glucan, is obtained by deacetylation of chitin which is produced in shells of crab, shrimps, insects, mushroom cell wall. Chitosan is a non-toxic, biocompatible and biodegradable natural polysaccharide (Li et al. 2013). Due to its valuable properties, chitosan offers advantages for adjuvant and vaccine delivery systems (Temsahy et al. 2014). Chitosan nanoparticles were easily formed by the ionic cross-linking and spontaneously gelation in aqueous solution; it is the reaction between amine groups of chitosan and phosphate groups of tripolyphosphate (TPP). Experimental results have proved that CNP was capable of efficiently delivering encapsulated antigens and enhancing the activation of macrophages and dendritic cells (Koppolu et al. 2013). In addition, it elicited a balanced Th1/Th2 response and induced a strong potential to increase both cellular and humoral immune responses (Wen et al.2011). As potential characteristics in vaccine application, CNP have been used as novel adjuvants for some vaccines as A/H1n1 Influenza Vaccine (Dzung et al. 2011), inactivated Avian Influenza (H9N2) Vaccine (Khalili et al. 2015) and live Newcastle disease virus vaccine (Zhao et al. 2012), but no data are available about using chitosan nanoparticle as adjuvant with RVFV inactivated vaccine Yeh et al. (2017) and Seferia and Martinez (2001).

Therefore, the present work aims to evaluate the adjuvant efficacy of CS and CNP and its ability to amplify the humoral and cell-mediated immune response against RVFV inactivated vaccine in comparison to aluminum hydroxide. The morphological character of CNP and the loading efficacy of RVF inactivated antigen on CNP were studied.

Materials and methods

Chitosan

Chitosan (100–300 kDa), were obtained from Acros-Organic com. Thermo Fisher Scientific, NJ, USA (Code 349051000 Lot A0376581.CAS:9012-76-4, the degree of deacetylation was 90%).

Virus strain

Local Egyptian RVFV strains, Pan Tropic-Menya Strain (Menya/Sheep/258) were used for vaccine production at RVFV department, Holding Company for Biological Products, Vaccines and Drugs (VACSERA), Giza, Egypt.

RVFV antigen

RVFV antigen was whole inactivated virus prepared according to the manual of standards for the vaccine (Kool et al. 2008). The RVFV strain was propagated on BHK-211. The inoculated flasks were daily microscopically examined for 5 days for the development of cytopathic effect (CPE). Flasks developed CPE reach about 75–85% were freeze and thawed three times for virus release, which collected and clarified from cell debris by centrifugation (8000 rpm, 30 min at 4 °C). The harvested virus was titrated (107.5 TCID /ml), inactivated using 0.2% formalin and filtrated through 0.22 μm membrane, purified using sucrose gradient method according to Murakami et al. (2014) and kept at – 80 °C. The RVFV antigen contains (32 μg/mL) protein.

Inactivation of RVFV vaccine

RVFV vaccine was a whole inactivated vaccine, inactivated by 0.2% formalin and has alum gel as an adjuvant and was tested for safety, sterility.

Preparation of chitosan nanoparticles

Chitosan nanoparticles were prepared according to Dzung et al. (2011) based on the ionic gelation method by using TPP as an ionic crosslinking agent with some modification. Briefly, Chitosan was dissolved in 0.5% acetic acid solution then adjusted to PH 5.5 and filtered through a 0.22 µm filter, then one volume of TPP solution (0.5 mg/ml) was added dropwise to three-volume of CS solution (1 mg/ml) under magnetic stirring for 60 min. The nanoparticles formed were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min, and then washed three times with deionized water, freeze-drying and store at 4 °C.

Loading RVFV antigen on chitosan or chitosan nanoparticles

One volume of RVFV antigen contains (32 μg/ml) protein, were added drop by drop to two-volume of chitosan solution (1 mg/ml) or chitosan nanoparticles (1 mg/l) under magnetic stirring for 1 h to completely adsorb the antigen onto the adjuvant. The RVFV-chitosan (RVFV-CS) or RVFV-chitosan nanoparticles (RVFV-CNP) were separated by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C then washed with deionized water and reconstituted to the original volume and kept for further analysis and mice vaccination.

Characterization of nanoparticles

Morphology of CNP or RVFV-CNP was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (HT7700; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The size and zeta potential of the particle were measured, using Particle sizer NICOMP_380 ZLS Dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument (PSS, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). To estimate the loading efficiency (% LE) of RVFV-CNP, the nanoparticles were separating by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant was collected and protein content (free RVFV antigen) in the supernatant was determined using Nano Drop Spectrophotometer ND 1000 (Thermo-Scientific, USA). The LE% was performed in triplicate. calculated according to the formula of (Zhao et al. 2012) (total amount of RVFV protein – the amount of RVFV protein in the supernatant)/total amount of RVFV protein] × 100].

Safety test

To estimate the safety of both RVFV-CS and RVFV-CNP Vaccines, 20 mice were separated into two groups, mice in 1st group immunized S/C with 0.8 mL RVFV-CS and mice in second group immunized S/C with 0.8 mL RVFV-CNP. Any abnormal signs were recorded for 2 weeks.

Experimental design

To study the efficiency of chitosan and chitosan nanoparticle as an adjuvant in comparison to aluminium hydroxide, 250 Swiss albino mice were allocated into five groups (50/each group). Mice in (G1) were injected with phosphate buffer saline and kept as a control group. Mice in (G2) were vaccinated with RVFV-CNP vaccine. Mice in (G3) were vaccinated with RVFV-CS vaccine. Mice in (G4) were vaccinated with RVFV-Alum based vaccine (commercial vaccine), while mice in (G5) were vaccinated with RVFV adjuvant free vaccine. (All mice were subcutaneously vaccinated two times with 2 weeks interval in dorsal skinfold with 0.2 ml of RVFV antigen containing (32 μg/mL) protein in the different vaccine formulations.) Serum samples were collected from all groups (6 samples/group) at zero time then weekly tell eighth week post second vaccination to estimate the RVFV neutralizing antibodies titer and IgG values against RVFV nucleoprotein as well as serum sample were collected at third and seventh-day post second vaccination to measure the levels of nitric oxide (NO) and lysozyme activity. Moreover, PM was collected from mice of all groups (6 samples/group) to estimate the phagocytic activities of PM, also Spleen of five mice from each group were collected for RNA extraction to estimate gene expression of IL2, IFN-γ and IL4 at third and seventh day post second vaccination.

(Care of laboratory animals and animal experimentation were conducted following the ethical guidelines of the medical ethical committee of the National Research Centre in Egypt).

Evaluation of innate immunity

Phagocytic activity of PM was estimated using Candida albicans according to Victor et al. (2003).The phagocytic % (number of macrophages engulf one or more Candida spores/100 macrophage cells) and phagocytic index (the number of engulfed Candida spores/number of phagocytic macrophage) were calculated. Lysozyme activity was measured by agarose plate lyses assay according to Peeters and Vantrapen (1977). Nitric oxide was determined by Griess reagent after deproteinization of serum and reduction of nitrate to nitrite using Copper plated Cadmium according to Yang et al. (2010).

Evaluation of humoral immunity

Detection of neutralized antibodies to RVFV vaccines

RVFV neutralizing antibodies were detected by serum neutralization test (SNT) as duplicates of twofold serial dilutions of sera starting from 1:10 were added to an equal volume of diluted RVFV into 96-well microtiter plates and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Then 105 Vero cells were added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 5 days with the daily microscopic investigation. The titers were expressed as the inverse highest dilutions giving 50% of CPE. Sera with titers higher than 10 were considered to be positive.

Detection of IgG antibodies to RVFV vaccines

Detection of IgG antibodies against RVFV vaccines were measured using competitive ELISA kit (ID vet Innovative Diagnostics Kits-France) following the manufacturer’s instructions through detection of anti-RVFV nucleoprotein antibodies in mice serum. The values of IgG antibodies are expressed as competition percentage of sample/negative % (S/N %). S/N % = OD of sample/OD of negative control × 100.

If S/N% ≤ 40% considered positive, 40% < S/N% ≤ 50% considered doubtful and S/N% > 50% considered negative.

The SYBR green Q RT-PCR assays

Real-time PCR was used for relative quantification of mRNA for IFN- γ, IL-2 and IL-4.

RNA extraction

Total RNA was purified from spleen tissue using the QIAamp RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Germany, GmbH) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Oligonucleotide primers

Primers used were supplied from Metabion (Germany) are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers sequences, target genes, and cycling conditions for SYBR green RT- PCR

| Target gene | Primers sequences | Reverse transcription | Primary Denaturation |

Amplification (40 cycles) | Dissociation curve (1 cycle) | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary denaturation | Annealing (Optics on) |

Extension | Secondary denaturation | Annealing | Final denaturation | |||||

| B-actin | GTG GGA ATT CGT CAG AAG GAC TCC TAT GTG |

50 °C 30 min |

94 °C 5 min |

94 °C 15 sec |

5 °C 30 s |

72 °C 30 s |

94 °C 1 min |

55 °C 1 min |

94 °C 1 min |

Sisto et al. (2003) |

| GAA GTC TAG AGC AAC ATA GCA CAG CTT CTC | ||||||||||

| IFN-γ | AAC GCT ACA CAC TGC ATC TTG G |

55 °C 30 s |

55 °C 1 min |

Sisto et al. (2003) | ||||||

| GAC TTC AAA GAG TCT GAG G | ||||||||||

| IL-2 | TCCACTTCAAGCTCTACAG |

52 °C 30 s |

52 °C 1 min |

Jain et al. (2009) | ||||||

| GAGTCAAATCCAGAACATGCC | ||||||||||

| IL-4 | TCG GCA TTT TGA ACG AGG TC |

55 °C 30 s |

55 °C 1 min |

Sisto et al. (2003) | ||||||

| GAA AAG CCC GAA AGA GTC TC | ||||||||||

SYBR green RT-PCR

Primers were utilized in a 25-µl reaction containing 12.5 µl of the 2× QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Germany, GmbH), 0.25 µl of Verso Enzyme Mix, 1.25 µl of RT enhancer (Thermo Scientific, Germany), 0.5 µl of each primer of 50 p mol concentration, 4 µl of water, and 6 µl of RNA template. The reaction was performed in a Stratagene MX3005P real time PCR machine.

Analysis of the SYBR green RT-PCR results

Amplification curves and comparative threshold cycles (CT) values were determined by strata gene MX3005P software. To estimate the variation of gene expression on the RNA of the different samples, the CT of each sample was compared with that of the control group according to the “ΔΔ Ct” method by Yuan et al. 2006) using the following ratio:(2−ct). Whereas ΔΔ Ct = Δ Ct reference – Δ Ct target. Normalization was done using the housekeeping gene (B. actin) (Sisto et al. 2003; Jain et al. 2009).

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean and standard errors. The significance of the results was evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and LSD at P < 0.05 using Statistical Package for Social Science SPSS (2006).

Results

Characterization of CNP and RVFV-CNP

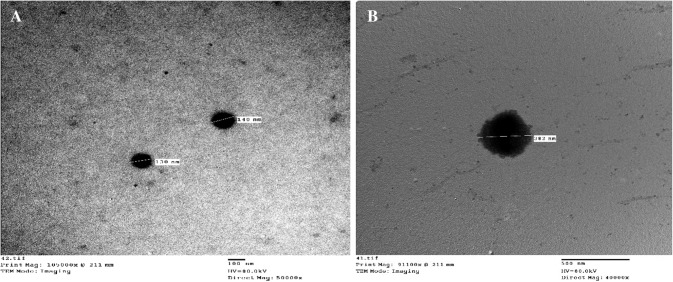

The results of TEM assay revealed that CNP and RVFV-CNP were regularly formed and have nearly spherical shapes, regularly formed with smooth surface (Fig. 1a, ab).

Fig. 1.

Transmission electron microscopy photomicrograph: a CNP b RVFV-C NP

Using DLS the average size was 140.4 ± 58.3 for CNP and 282 ± 110 nm for RVFV-CNP with polydispersity index 0.172 and 0.177, respectively. The surface zeta potential was positive 16.7 and 9.24 mV, respectively. RVFV loading on CNP was investigated and it was shown that the loading efficacy of RVFV on CNP was 93.75%.

Safety test

The in-vivo safety test of RVFV-CNP and RVFV-CS vaccine demonstrated that the feeding and drinking were normal. No clinical sign or necropsy lesions were observed in injected mice.

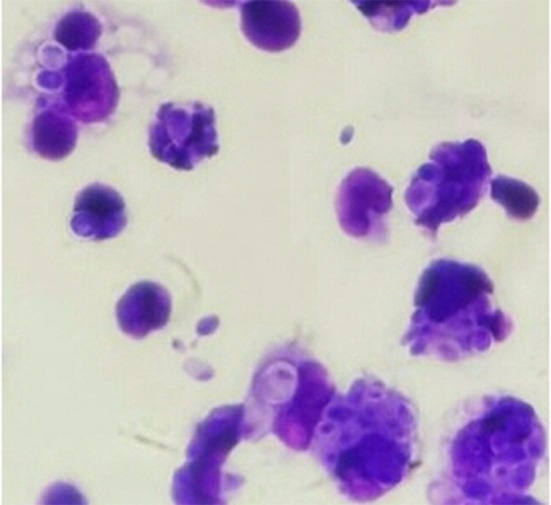

Innate immune response

Phagocytic activity of PM showed a significant increase in both phagocytic % and index in mice vaccinated with RVFV-CNP, RVFV-CS and alum-based vaccine at third day post second vaccination, also with those vaccinated with RVFV-CNP and RVFV-CS vaccine at seventh day post second vaccination comparing with control and adjuvant free vaccine. The highest values were recorded in mice vaccinated with RVFV-CNP (Fig. 2; Table 2). Lysozyme activity was significantly increased in mice vaccinated with RVFV-CNP or RVFV-CS comparing with other groups at the third and seventh day post second vaccination. The level of serum NO in mice vaccinated with the alum-based vaccine (G4) was significantly increased than that of all groups at third day post second vaccination (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Mice peritoneal macrophages from RVFV-CNP group engulfed Candida albicans spores (Giemsa stain × 100)

Table 2.

Phagocytic percentage and phagocytic index of peritoneal macrophages of mice vaccinated with different vaccine formulations

| Parameter | Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time post 2nd vaccination | G1 (control) | G2 (RVFV-CNP) | G3 (RVFV-CS) | G4 (RVFV-alum) | G5 (RVFV- Ag) | |

| Phagocytic percent | 3rd day | 56.33 ± 1.15c | 80.83 ± 2.09a | 66.33 ± 0.85b | 68.17 ± 1.71b | 57.50 ± 1.12c |

| 7th day | 54.31 ± 1.72c | 86.11 ± 1.21a | 70.62 ± 0.91b | 55.12 ± 1.51c | 53.01 ± 1.92c | |

| Phagocytic index | 3rd day | 2.68 ± 0.03c | 5.96 ± 0.12a | 3.92 ± 0.08b | 3.22 ± 0.11bc | 2.72 ± 0.04c |

| 7th day | 2.59 ± 0.02c | 6.01 ± 0.09a | 4.21 ± 0.03b | 2.92 ± 0.14c | 2.62 ± 0.02c | |

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (n = 6). Mean with different superscript small letters indicate significantly different in the same row (between groups) (P < 05)

Table 3.

Serum lysozyme (µg/ml) activity and nitric oxide values (µmol/ml) of mice vaccinated with different vaccine formulations

| Parameter | Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time post 2nd vaccination | G1 (control) | G2 (RVFV-CNP) | G3 (RVFV-CS) | G4 (RVFV-Alum) | G5 (RVFV-Ag) | |

| Lysozyme (µg/ml) | 3rd day | 177 ± 3.61b | 227 ± 9.71a | 222 ± 11.34a | 175 ± 5.86b | 192 ± 5.64b |

| 7th day | 170 ± 4.3bb | 245 ± 9.57a | 210 ± 17.29a | 163 ± 6.45b | 182 ± 3.62b | |

| Nitric oxide (µmol/ml) | 3rd day | 8.10 ± 0.86b | 12.17 ± 0.28ab | 11.73 ± 0.94b | 15.21 ± 0.98a | 8.35 ± 1.37b |

| 7th day | 7.36 ± 0.22b | 11.47 ± 0.63ab | 10.13 ± 0.78ab | 12.49 ± 0.51a | 7.87 ± 0.99b | |

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (n = 6). Mean with different superscript small letters indicate significantly different in the same row (between groups) (P < 0.05)

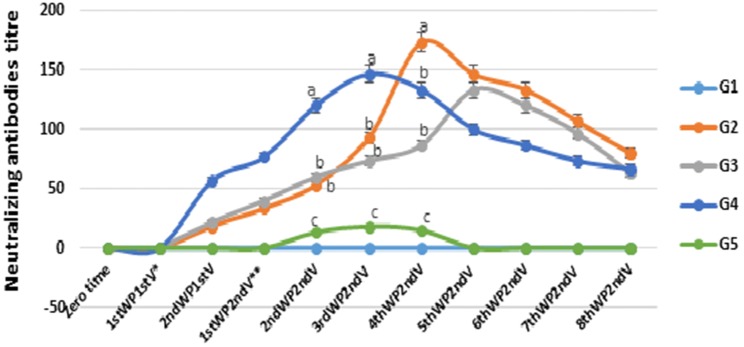

Antibody response against RVFV vaccine

The neutralizing antibodies titer against RVFV vaccines are shown in Fig. 3, where the mice vaccinated with the alum-based vaccine (RVFV-Alum) (G4), recorded the highest values until third week post second vaccination. However, the neutralizing antibody titer of mice immunized with RVFV-CNP (G2) and RVFV-CS (G3) was elevated gradually and beaked at fourth and fifth week post second vaccination, respectively with the highest titer tell the end of experiment.

Fig. 3.

The RVFV neutralizing antibody titer in mice vaccinated with different inactivated RVFV vaccines

The titers were expressed as the inverse highest dilutions giving 50% of CPE. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 6). Mean with different superscript small litters indicate significantly different in the same time (between groups) (P < 05). G1: control group injected with PBS, G2: mice vaccinated with RVFV-CNP vaccine; G3: mice vaccinated RVFV-CS vaccine; G4: mice vaccinated with RVFV-Alum based vaccine; G5: mice vaccinated with RVFV adjuvant free vaccine (RVFV-Ag). *Week post first vaccination **week post second vaccination. (0) have neutralization titer < 10.

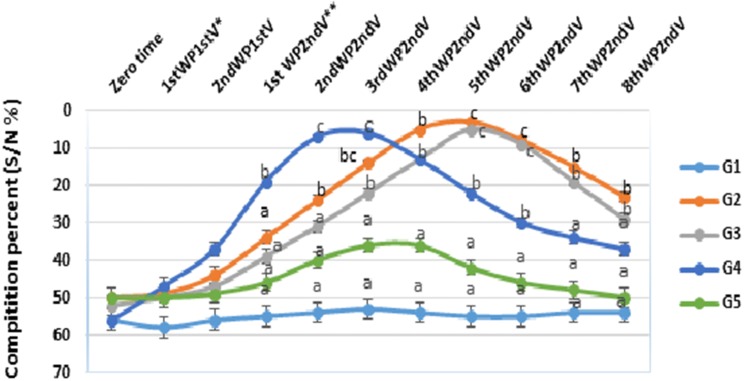

Also, the humoral immune response against RVFV vaccines were determined by measuring IgG against RVFV nucleoprotein (Fig. 4) where the antibodies values of mice vaccinated with alum-based vaccine (RVFV-Alum) (G4) beaked at third week post second vaccination. However, antibody values of mice immunized with RVFV-CNP (G2) and RVFV-CS (G3) were beaked at fifth week post second vaccination with significantly high values at that time comparing with other groups.

Fig. 4.

Serum IgG antibodies against RVFV nucleoprotein (using competitive ELISA) induced by different inactivated RVFV vaccines in mice

The values are expressed as competition percentage (OD of the sample /OD of the negative control × 100)—Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (n = 6). Mean with different superscript small litters indicate significantly different in the same time (between groups) (P < 05). G1: control group injected with PBS, G2: mice vaccinated with RVFV-CNP vaccine; G3: mice vaccinated RVFV-CS vaccine; G4: mice vaccinated with RVFV-Alum based vaccine; G5: mice vaccinated with RVFV adjuvant free vaccine (RVFV-Ag). *Week post first vaccination **week post-second vaccination.

Cytokine mRNA gene expression

The level of gene expression in splenocytes of vaccinated mice was estimated using the SYBR Green RT-qPCR assay (Table 4) Both RVFV-CNPand RVFV -CS vaccines (G2&G3) induced a significantly higher expression of IFN-y and IL-2 at third and seventh day post second vaccination than other vaccine formulation. While vaccination with RVFV-Alum based vaccine resulted in the highest expression of IL-4 and relatively lower expression of IFN-y and IL-2 at third and seventh day post second vaccination. While mice vaccinated with adjuvant free vaccine expressed very low levels of all cytokine mRNA.

Table 4.

Cytokine mRNA gene expression (fold change of control) of mice vaccinated with different vaccine formulations

| Parameter | Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time post 2nd vaccination | G1 (control) | G2 (RVFV-CNP) | G3 (RVFV-CS) | G4 (RVFV-Alum) | G5 (RVFV-Ag) | |

| IFN-γ | 3rd day | 1 | 19.7 ± 0.31a | 7 ± 0.57b | 3.50 ± 1.21c | 0.4 ± 0.05d |

| 7th day | 1 | 15.0 ± 3.05a | 15.25 ± 0.5a | 2.1 ± 0.43b | 1.25 ± 0.58b | |

| IL-2 | 3rd day | 1 | 18.50 ± 1.33a | 9.75 ± 0.88b | 4.7 ± 0.34c | 0.52 ± 0.03d |

| 7th day | 1 | 14.2 ± 2.08a | 12.75 ± 0.67a | 2.7 ± 0.57b | 0.65 ± 0.12c | |

| IL-4 | 3rd day | 1 | 20.4 ± 2.01b | 13.75 ± 0.89c | 26.7 ± 1.53a | 5.25 ± 0.67d |

| 7th day | 1 | 23.25 ± 0.89b | 15.75 ± 0.33c | 29.75 ± 1.33a | 4.75 ± 0.75d | |

SYBR green real-time RT-PCR for evaluation of mRNA expression of IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-4 genes in mice spleen from groups immunized with different vaccine formulations. Relative expression fold change was calculated by 2−ΔΔCt method and β-actin was used as the endogenous reference gene to normalize the expression level of target + gene. Values represent means ± SE. Mean with different superscript small letters indicate significantly different in the same row (between groups) (P < 0.05)

SYBR green real-time RT-PCR was used for evaluation of mRNA expression of IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-4 genes in mice spleen from groups immunized with different vaccine formulations. Relative expression fold change was calculated by 2−ΔΔCt method and β-actin was used as the endogenous reference gene to normalize the expression level of target + gene. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 6). Mean with different superscript small letters indicate significantly different in the same row (between groups) (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Adjuvants are an important gateway to better vaccines. Ideally, adjuvant should be biodegradable, not be immunogenic themselves, offer excellent safety, tolerability and ease of manufacture (Pulendran and Ahmed 2006). Due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxic nature and easily modified into desired shapes and sizes, chitosan may be a suitable polymer to be used as a delivery vehicle for vaccines (Van der Lubben et al. 2001). In the present study, the chitosan possesses a negative charge and it is the most popular because of its non-toxic property and Quick gelling ability. The formation of CNP takes place due to the attraction between positively charged chitosan and negatively charged TPP (Yang et al. 2009).

Morphologically, the TEM images of CNP prepared in the present work were found to be spherical in shape, smooth surface, have poly-dispersed nature and its average size obtained using DLS, was (145 nm). In the same regard, Han et al. (2016) obtained CNP with an average size of 127.9 nm and Hassani et al. ( 2015) prepared chitosan–TPP nanoparticles with a mean size around 90–100 nm, also Dzung et al. (2011) obtained CNP with 106.77 nm. Whereas the average particle size of the prepared RVFV-CNP was 282 ± 110 nm by DLS. Zhao et al. (2012) obtained NDV-loaded CNP with a mean size of 371.1 nm. The wide variation of nanoparticles size may be due to different chitosan polymeric properties, CS/TPP ratio, and other condition used during preparation (AL-Nemrawi et al. 2018). Zeta potential is the surface charge which greatly influences particle stability in suspension through the electronic repulsion between particles. It can also determine nanoparticle interaction in vivo condition. The obtained results showed that the Zeta potential of CNP was 16.7 mV which reduced to 9.24 mV in RVFV-CNP. This result was supported by that of Mirzaei et al (2017) who obtained CNP with a zeta potential of 19.8 Mv and Zhao et al. (2012) who recorded that the zeta potential of CNP containing the lentogenic virus vaccine against NDV was 2.84 mV.

The safety of the prepared RVFV-CNP and RVFV-CS were tested by safety test in mice in which the dose was four times the normal dosage showing a high level of safety in mice.

Regarding the innate immune responses of mice following vaccination with different vaccine formulations, RVFV-CNP vaccinated mice showed a significant increase in both phagocytic % and index comparing with other groups. Lysozyme activity was significantly increased in mice immunized with RVFV-CNP and that immunized with RVFV-CS comparing with other groups, which indicate an enhancement of macrophage activity. Several researchers have found that chitosan could be a potent activator of macrophages and natural killer cells (Peluso et al.1994). Also, chitosan can increase the pinocytic activity of macrophages cell lines (Wu et al. 2015). In the case of nitric oxide assay, the alum–based vaccine elicited high level comparing with RVFV-CNP and RVFV-CS vaccine. This result comes following Rajan et al. (1996) who found that alum can induce NO synthesis in murine macrophages. This may be attributed to the fact that alum act as an inflammatory agent, provoke local tissue irritation and long inflammatory reaction at the site of injection which leads to the inflammatory cascade activation.

The obtained results of gene expression of IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 revealed that RVFV-CNP vaccine induced the highest values of IFN- γ and IL-2 at third and seventh day post second vaccination, while the highest values of IL-4 were recorded in mice immunized with the alum-based vaccine (RVFV-alum), followed by mice immunized with RVFV-CNP. The gene expression of IFN-γ and IL-2 were used to investigate type-1 immune response (T helper 1) which promote cell-mediated immunity and activated macrophages. The gene expression of IL-4 was used to investigate type-2 immune response (T helper 2) which promotes humoral immunity through secretion of antibodies from B-lymphocyte. In the same regard, Huang et al. (2018) recorded that immunization with chitosan-DNA nanoparticles vaccine triggered the higher levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 in comparison to other groups.

The values of both neutralizing antibody and IgG antibodies against RVFV nucleoprotein of mice immunized with alum inactivated vaccine peaked earlier than that immunized with RVFV-CNP or RVFV-CS. However, in RVFV-CNP and RVFV-CS groups, the neutralizing antibody and IgG increased gradually and peaked at fourth and fifth week post second vaccination respectively with long duration and with much better value at the end of the experiment. These results were supported by Kahlili et al. (2015) who recorded that the Avian Influenza virus (AIV) loaded into CNP vaccines induce appropriate antibody titers and significantly enhances the immunogenicity of inactivated AIV. Also, Zaharoff et al. (2007) recorded that chitosan enhanced antigen-specific antibody titers over fivefolds and chitosan adjuvant was better than Freund and alum.

The mechanism of action of chitosan and CNP as parental adjuvant include their immune-stimulating activity such as increasing macrophage activity, inducing cytokines and augmenting antibody responses (Wardani et al. 2018). Also, loaded RVFV antigen with nanometer size are easy to go through the cell membrane and release RVFV antigen to stimulate B cells and T cells and induce strong immune responses against the antigen. Moreover, RVFV antigen-loaded chitosan nanoparticles can be maintainable in tissue longer than the other carriers and the duration of the response is longer (Dzung et al. 2011). A recent study pinpointed that chitosan stimulates Th1 cell cytokine production as a consequence of its triggering of type I IFN-dependent dendritic cell activation. This pathway involves the phagocytic uptake of the CS which induces mitochondrial stress leading to reactive oxygen species production and the release of mitochondrial DNA, which in turn binds to cyclic-di-GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) and generating cyclic di-nucleotides (CDNs) which stimulate the stimulator of IFN genes (STING) pathway. These cytokines were then responsible for activation of dendritic cell (Carroll et al. 2016) which upregulate the expression of MHC I/II along with other co-stimulatory surface proteins that are required for processing, and antigen presentation to T cells, and production of cytokines required for T-cell activation and induction of cellular immunity (West et al. 2004).

Conclusion

In the present study, Chitosan nanoparticles prepared by gel ionic method can efficiently load inactivated RVFV antigen. In vivo vaccination of mice showed that the RVFV-CS and RVFV-CNP vaccines are safe, strongly stimulate the innate and adaptive immune response and particularly promotes the developments of Th1 response manifested by significantly induce gene expression of IFN-γ and IL-2, Chitosan nanoparticles show the better efficacy on enhancing the immune response against RVFV than other groups. More studies need to be conducted to further optimize these chitosan nanoparticles for use in the commercial application used in vaccines instead of alum.

Acknowledgements

This work supported by the Animal Health Research Institute-Egypt, Holding Company for Biological products, Vaccines and Drugs (VACSERA)-Egypt and the National Research Centre-Egypt.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Animal Health Research Institute and the National Research Centre-Egypt.

References

- AL-Nemrawi N, AL-Sharif SM, Daver RH. Preparation of chitosan-TPP nanoparticles: the influence of chitosan properties and formulation variables. Int J Appl Pharm. 2018;10(5):60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Averhoff F, Mahoney F, Coleman P, Schatz G, Hurwitz E. Immunogenicity of hepatitis B vaccines: implications for persons at occupational risk of hepatitis B virus. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll EC, Jin L, Mori A, Muñoz-Wol N, Oleszycka E, Moran HBT, Mansouri S, Entee P, Lambe E, Agger EM, Andersen P, Cunningham C, Hertzog P, Fitzgerald KA, Bowie G, Lavelle EC. The vaccine adjuvant chitosan promotes cellular immunity via DNA sensor cGAS-STING-dependent induction of type I interferons. Immunity. 2016;44(3):597–608. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzer JA. The pathology of Rift Valley fever. II. Lesions occurring in field cases in adult cattle, calves and aborted foetuses. J Vet Res. 1982;49:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Confavreux C, Suissa A, Saddier P, Bourdes V, Vukusic S. Vaccinations and the risk of relapse of multiple sclerosis. Vaccines in multiple sclerosis group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:319–326. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzung NH, Ha NT, Van DT, Phuong NTL, Puynh NTN, Hiep LV. Chitosan nanoparticle as a novel delivery system for A/H1n1 influenza vaccine: safe property and immunogenicity in mice. World Acad Sci Eng Technol. 2011;60:1839–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis DS, Shirodaria PV, Fleming E, Simpson D. Morphology and development of RVF virus in vero-cell cultures. J Med Virol. 1988;24(2):161–173. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890240205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler DJ. The global emergence/resurgence of arboviral diseases as public health problems. Arch Med Res. 2002;33:330–342. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(02)00378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta NK, Tomar P, Sharma V, Dixit VK. Development and characterization of chitosan coated poly-(ε-caprolactone) nanoparticulate system for effective immunization against influenza. Vaccine. 2011;29(48):9026–9037. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han HD, Byeon Y, Jang JH, Jeon HN, Kim GH, Kim MG, Pack CG, Kang TH, Jung ID, Lim YT, Lee YJ, Lee JW, Shin BC, Ahn HJ, Sood AK, Park YM. In vivo stepwise immunomodulation using chitosan nanoparticles as platform nanotechnology for cancer immunotherapy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38348. doi: 10.1038/srep38348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassani S, Laouini A, Fessi H, Charcosset C. Preparation of chitosan–TPP nanoparticles using micro engineered membranes—effect of parameters and encapsulation of tacrine. Coll Surf A. 2015;482(5):34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Himeidan YE. Rift valley fever: current challenges and future prospects. Res Rep Trop Med. 2016;7:1–9. doi: 10.2147/RRTM.S63520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Song X, Jing J, Zhao K, Shen Y, Zhang W, Yue B. Chitosan-DNA nanoparticles enhanced the immunogenicity of multivalent DNA vaccination on mice against Trueperella pyogenes infection. J Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16(8):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0337-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Yadav H, Sinha PR, Marotta F. Modulation of cytokine gene expression in spleen and Peyer’s patches by feeding Dahi containing probiotic Lactobacillus casei in mice. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2008.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenawy MA, Abdel-Hamid YM, Beierc JC. Rift Valley Fever in Egypt and other African countries: historical review, recent outbreaks and possibility of disease occurrence in Egypt. Acta Trop. 2018;181:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalili I, Ghadimipou R, Khalili MT. Evaluation of immune response against inactivated avian influenza (H9N2) vaccine, by using chitosan nanoparticles. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2015;8(12):e27035. doi: 10.5812/jjm.27035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kool M, Soullié T, Van Nimwegen M, Willart MA, Muskens F, Jung S, Hoogsteden HC, Hammad H, Lambrecht B. Alum adjuvants boosts adaptive immunity by inducing uric acid and activating inflammatory den-dritic cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205(4):869–882. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppolu B, Zaharoff DA. Effect of antigen encapsulation in chitosan particles on uptake, activation and presentation by antigen presenting cells. Biomaterials. 2013;34(9):2359–2369. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.11.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Min M, Du N, Gu Y, Hode T, Naylor M, Chen D, Nordquist RE, Chen WR. Chitin, chitosan, and glycated chitosan regulate immune responses: the novel adjuvants for cancer vaccine. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:387023. doi: 10.1155/2013/387023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrack P, McKee AS, Munks MW. Towards an understanding of the adjuvant action of aluminium. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:287–293. doi: 10.1038/nri2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei F, Mohammadpour DN, Avadi MR, Rezayat MA. New approach to antivenom preparation using chitosan nanoparticles containing Echis carinatus venom as a novel antigen delivery system. IJBR. 2017;16(3):858–867. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S, Terasaki K, Ramirez SI, Morrill JC, Makino S. Development of a novel, single-cycle replicable rift valley fever vaccine. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(3):2746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office International Des Epizooties (OIE) (2008) Manual of standards for diagnostic tests and Vaccines, 6th edn. World Organization for Animal Health

- Peeters TL, Vantrapen GR. Factors influencing lysozyme determination by lysoplate method. Clin Chim Acta. 1977;74(3):217–255. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(77)90288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluso G, Petillo O, Ranieri M, Santin M, Ambrosio LD, Calabro D, Avallone B, Balsamo G. Chitosan-mediated stimulation of macrophage function. Biomaterials. 1994;15:1215–1220. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulendran B, Ahmed R. Translating innate immunity into immunological memory: implications for vaccine development. Cell. 2006;124:849–863. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan TV, Porte P, Yates JA, Keefer L, Shultz LD. Role of nitric oxide in host defense against an extracellular, metazoan parasite, Brugia malayi. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3351–3353. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3351-3353.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seferia PG, Martinez ML. Immune stimulating activity of two new chitosan containing adjuvant formulation. Vaccine. 2001;19:661–668. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisto F, Miluzio A, Leopardi O, Mirra M, Boelaert JR, Taramelli D. Differential cytokine pattern in the spleens and livers of BALB/c mice infected with Penicillium marneffei: protective role of gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 2003;71(1):465–473. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.465-473.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS (2006) Statistical Package for Social Science, SPSS for windows Release Standard Version, Copyright SPSS Inc

- Temsahy MME, Kerdany EDHE, Eissa MM, Shalaby TI, TalaatI M, Mogahed NMFH. The effect of chitosan nanospheres on the immunogenicity of Toxoplasma lysate vaccine in mice. J Parasitic Dis. 2014;40:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s12639-014-0546-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulanova M, Tarkowski A, Hahn-Zoric M, Hanson LA. The common vaccine adjuvant aluminum hydroxide up-regulates accessory properties of human monocytes via an interleukin-4-dependent mechanism. Infect Immun. 2001;69(2):1151–1159. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.1151-1159.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Lubben IM, Verhoef JC, Borchard G, Junginger HE. Chitosan and its derivatives in mucosal drug and vaccine delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;14:201–207. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(01)00172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor VM, Rocha M, La Fuenle De. Regulation of macrophage function by the antioxidant N-acetyle cysteine in mouse-oxidative stress by endotoxin. Int Immunopharmacol. 2003;3:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wack A, Rappuoli R. Vaccinology at the beginning of the 21st century. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardani G, Sudjarwo SA. Immunostimulatory activity of chitosan nanoparticles on Wistar Albino Rats. Pharmacog J. 2018;10(5):892–898. [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZS, Xu YL, Zou XT, Xu ZR. Chitosan nano-particles act as an adjuvant to promote both Th1 and Th2 immune responses induced by ovalbumin in mice. Mar Drugs. 2011;9:1038–1055. doi: 10.3390/md9061038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MA, Wallin RP, Matthews SP, Svensson HG, Zaru R, Ljunggren HG, Prescott AR, Watts C. Enhanced dendritic cellantigen capture via toll-like receptor-induced actin remodeling. Science. 2004;305:1153–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1099153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Wen ZS, Xiang XW, Huang YN, Gao Y, Qu YL. Immuno-simulative activity of low molecular weight chitosans in RAW264.7 macrophages. Mar Drugs. 2015;13(10):6210–6225. doi: 10.3390/md13106210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Fu J, Wang T, He N. Chitosan/sodium tripolyphosphate nanoparticles: preparation, characterization and application as drug carrier. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2009;5:591–595. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2009.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Sun Q, Raza Asim A, Jiang X, Zhong B, Shahzad M, Zhang F, Han Y, Lu S. Nitric oxide in both bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and serum is associated with pathogenesis and severity of antigen-induced pulmonary inflammation in rats. J Asthma. 2010;47(2):135–144. doi: 10.3109/02770900903483808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh MY, Shih YL, Chung HY, Chou J, Lu HF, Liu CH, Liu JY, Huang WW, Peng SF, Wu LY, Chung JG. Chitosan promotes immune responses, ameliorates glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase and glutamic pyruvic transaminase, but enhances lactate dehydrogenase levels in normal mice in vivo. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:2483–2490. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JS, Reed A, Che F, Stewart CN. Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC Bioinform. 2006;7:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharoff DA, Rogers CJ, Hance KW, Schlom J, Greiner JW. Chitosan solution enhances both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to subcutaneous vaccination. Vaccine. 2007;25:2085–2094. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K, Chen G, Shi XM, Gao TT, Li W, Zhao Y, Zhang FQ, Wu J, Cui X, Wang YF. Preparation and efficacy of a live Newcastle disease virus vaccine encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e53314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]