Abstract

Purpose

To call attention to the fact that cumulative live birth (LB) proportions exhibit an inverted pattern to that displayed by each individual oocyte retrieval cycle (ORC-specific LB proportions) as well as when grouping together all the ORCs undergone by a woman (TNORC-specific LB proportions).

Methods

A retrospective study of 1433 infertile women that had a LB using autologous fresh or frozen embryos and/or dropped out of IVF/ICSI treatment after completing a maximum number of three treatment cycles. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) and standard and landmark Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were applied.

Results

A standard Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that cumulative LB proportions rose as number of ORCs increased (0.320, 0.484, and 0.550 at ORC 1, 2, and 3, respectively). In contrast, landmark ORC-specific LB proportions showed an inverted pattern (0.320, 0.242, and 0.127 at ORC 1, 2, and 3, respectively). GEE models revealed that women’s clinical outcomes decreased as TNORCs increased. In particular, compared to women that experienced just one ORC, women that underwent two and three ORCs displayed higher incidences of cycle cancellations before either oocyte retrieval or embryo transfer, and clinical pregnancy losses, and lower odds of LB.

Conclusion

Infertile women should be informed that cumulative LB probabilities exhibit an inverted pattern to that displayed by each individual ORC as well as when grouping together all the ORCs undergone by a woman.

Keywords: Cumulative live birth, Fecundity, In vitro fertilization, Oocyte retrieval cycle

Introduction

It is known that, in women without a history of infertility who are in a stable relationship with a male partner and attempting to conceive naturally without the use of fertility treatments, fecundability drops rapidly with time since attempting pregnancy [1]. Such a decrease occurs because the most fertile couples are the first in getting pregnant and, thereafter, they are not considered in the pool of women with worse fecundability [1]. In contrast, after applying censoring life-table methods, cumulative pregnancy proportions at 12 cycles of attempting pregnancy are consistently higher than those found at 6 cycles [1]. This increase takes place because cumulative probabilities are cohort probabilities estimated by taking into account all the women entered into the study irrespectively of their fecundability. Note that the meaning of “fecundability” differs from other closely related terms such as “fertility” or “fecundity.” Fecundability is defined as the probability of a pregnancy, during a single menstrual cycle in a woman with adequate exposure to sperm and no contraception, culminating in a live birth (LB). Fertility is defined as the capacity to establish a clinical pregnancy. Finally, fecundity is clinically defined as the capacity to have a LB [2].

Like in fecundability in women without a history of infertility [1], all the infertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) treatments do not have the same fecundity. In this population of infertile women, the most-fecund women are also the first in becoming pregnant and having a LB, whereas less-fecund women take longer to have a LB or even never experience a LB event. In other words, in the general population of IVF/ICSI women, cycle-specific LB percentages decrease as number of oocyte retrieval cycles (ORCs) undergone by women rises [3–9]. In contrast, cumulative probabilities of LB increase with number of ORCs [3, 5–8].

In 2005, Daya [10] opened a new debate about the validity of using a survival analysis methodology to estimate the effectiveness of assisted reproduction treatment (ART) and facilitate the women’s decision-making process about pursuing further IVF/ICSI treatments after one or more unsuccessful attempts. The comprehensive review by Daya [10] evidenced several biases in the assumptions made in literature when estimating cumulative percentages. Two important violations of these assumptions were the use of a “treatment cycle” as the scale for measuring the passage of time, and the occurrence of informative censoring, i.e., those drop-outs from successive treatments related with the outcome. Accordingly, Daya [10] concluded that survival analysis methodology was not appropriate for reporting and comparing ART results, and decision making.

Recently, Modest et al. [8] used a Kaplan-Meier incorporating weighting approach to control for the high drop-out percentages evidenced in ART studies. Although this approach constitutes a clear improvement in survival analysis methodology, the scale for measuring the passage of time is still based on a “treatment cycle.” Another important limitation of the use of cumulative probabilities as the unique predictive tool for LB is the fact that they may become a “psychological trap” for infertile women. By definition, the concept of “cumulative probability” involves an increase in cumulative probability as the unit of the scale for measuring the passage of time, in this case “treatment cycle,” rises. Thus, if infertile women are informed only about their cumulative chances of success across multiple treatment cycles, they may be prone to have more treatment cycles after one or more unsuccessful attempts, unless they are advised not to pursue further treatment based on additional information collected in a previous treatment cycle. Notwithstanding, we should bear in mind that patient counseling and decision making are very challenging and, sometimes, unpredictable processes. In fact, some women may not wish to undergo IVF/ICSI treatment even if they have the best chance of success, whereas others may embark on multiple treatment cycles despite being strongly counseled against due to the presence of poor prognosis factors and previous unsuccessful treatment cycles [11].

The present study aims to call attention to the fact that cumulative LB proportions exhibit an inverted pattern to that displayed by each individual oocyte retrieval cycle (ORC-specific LB proportions) as well as when grouping together all the ORCs undergone by a woman (TNORC-specific LB proportions). This information may be particularly valuable for infertile women with low or zero fecundity, which will most likely never have a LB after undergoing many treatment cycles.

Methods

Study design

This is a retrospective analysis of IVF/ICSI data from 1433 couples enrolled in the Assisted Reproduction Unit of the Valencia University Clinic Hospital from January 2009 to July 2018. The study was exclusively focused on women that had a LB using autologous fresh or frozen embryos and/or dropped out of IVF/ICSI treatment after completing a given treatment cycle, i.e., an autologous cycle with no frozen embryos left over for further transfers. As LB proportions were estimated on a per cycle basis, those women that dropped out of IVF/ICSI treatment before transferring all the available frozen embryos were excluded from the study.

Note that both the Spanish Royal Decree-Law 1030/2006 and the Order SSI/2065/2014 establish that IVF treatment using autologous oocytes/spermatozoa or donated spermatozoa should be applied in the National Health System only if (1) couples have not a previous common and healthy child; (2) woman’s age is < 40 years at the start of the infertility study; and (3) there is no evidence of poor ovarian reserve. We should also take into account that, according to law, a maximum number of three treatment cycles of ovarian stimulation is allowed. Thus, only women that had a LB in the first, second, or third ORC and/or experienced just one, two, or three complete ORCs were entered into the study. All the stages of treatment from the start of ovarian stimulation to the outcomes of the fresh and/or subsequent frozen embryo transfers were taken into consideration. Consequently, cycles cancelled before either oocyte retrieval or a particular embryo transfer were included into the final statistical analysis [12]. Furthermore, in order to reduce the variability among women in length of time required to complete IVF/ICSI treatments [10], a 24-month interval was established as a follow-up limit for women to undergo three complete oocyte retrieval cycles. Women who did not complete treatment in 24 months, were excluded from the study.

Note that women that succeeded in having a healthy LB in a particular oocyte retrieval cycle did not experience further embryo transfers (in the event they had spare frozen embryos available for further transfers) nor further ORCs. A healthy LB was defined as the birth of a living child without major congenital malformations or serious diseases that pose a short-term risk of death or permanent physical/mental disability. No women exhibiting both an unhealthy LB and spare frozen embryos available applied for further transfers or oocyte retrieval cycles. Thus, all the women entered into the study displayed either none or just a single episode of LB. LB included the birth of at least one living child, regardless of the duration of gestation.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of demographic and clinical characteristics of couples entered into the study, stratified by TNORCs undergone by women, was initially performed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) or chi-squared test was used to compare quantitative and categorical variables, respectively, among the three levels of TNORCs.

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) models were applied to show the effect of TNORCs experienced by women on IVF/ICSI outcomes. GEE models allow for analysis of repeated measurements or other correlated observations such as clustered data, especially when they are binary or in the form of counts [13]. In a previous study [14], we found that the goodness-of-fit of GEE models improved on most occasions after adjusting standard errors for the potential correlation among women exhibiting the same infertility etiology. Therefore, variables were arranged in a hierarchical two-level structure with women starting ovarian stimulation clustered within female infertility etiology. We considered two approaches when applying GEE models depending on whether the response variable was binary or in the form of counts. A logit link and a binomial distribution for binary outcomes, and a log link and a Poisson distribution for count variables were used. As we assumed that measurements were correlated, a robust variance estimator was used to calculate the variance-covariance matrix of estimated parameters. The goodness-of-fit Quasi-likelihood under Independence Model Criterion (QIC) was applied to choose between two working correlation structures: the exchangeable and independent matrix. The working correlation structure that had the smallest QIC was considered as the matrix that provided the best goodness of fit [15]. This matrix was selected and used for data analysis. In particular, the exchangeable working correlation matrix was used to analyze the effect of TNORCs on clinical pregnancies, clinical pregnancy losses, and LB, whereas the independent working correlation matrix was applied to analyze the effect of TNORCs on number of cycle cancellations before either oocyte retrieval or embryo transfer.

The sequential procedure by Benjamini and Hochberg [16] was applied to control for false discovery rate, i.e., the expected fraction of tests that are declared significant in a study despite the null hypotheses are true, and adjust the P value [17].

One standard or three landmark Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were used to estimate either cumulative or cycle-specific LB proportions, respectively, at each ORC. In landmark analysis, a time point, known as the landmark time (in the present context, an ORC), occurring during the follow-up period is designated to analyze only those subjects who have survived (in the present context, women that did not have a LB) until the landmark time [18]. Although landmark Kaplan-Meier survival analysis can estimate cumulative LB proportions after a particular landmark ORC, we used three landmark analyses to evaluate cycle-specific LB proportions at each ORC, i.e., at each baseline time designated by the landmark. The following sets of data were selected to estimate landmark LB proportions at each ORC: (1) All the women entered into the study to estimate the LB proportion at ORC 1; (2) only women that did not have a LB at ORC 1 and underwent two or three ORCs to estimate the LB proportion at ORC 2; and (3) only women that did not have a LB at ORC 1 and 2 and experienced three ORCs to estimate the LB proportion at ORC 3.

In both the standard and the landmark Kaplan-Meier approach, the potential selection bias induced by loss of follow-up related to risk of LB (informative censoring) was controlled for by assuming that all the women that dropped out of IVF/ICSI treatment after completing a given treatment cycle did not have a LB for the duration of the remaining study period (three ORCs), i.e., we assumed a conservative scenario [10]. Like in GEE models, data were arranged in a hierarchical two-level structure with “women starting ovarian stimulation” clustered within “female infertility etiology” to calculate standard errors.

All the analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24; © Copyright IBM Corporation and its licensors 1989, 2016) and R version 3.5.1 [19].

Results

Table 1 shows the clusters of women established according to their infertility etiology. The most common causes of infertility were unknown factor (26.9%) and multiple female factors (26.7%), followed by uterine factor (12.8%), diminished ovarian reserve (10.5%), and ovulatory dysfunction (9.4%). Less common etiologies included tubal factor (6.4%), endometriosis (5.0%), and other factors (2.4%).

Table 1.

Clusters of women established according to their infertility etiology

| Female infertility etiology | n |

|---|---|

| Tubal factor | 91 (6.4)a |

| Uterine factor | 183 (12.8) |

| Endometriosis | 73 (5.0) |

| Ovulatory dysfunction | 135 (9.4) |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 150 (10.5) |

| Unknown factor | 385 (26.9) |

| Multiple female factors | 382 (26.7) |

| Other factors | 34 (2.4) |

| Total | 1433 |

aValues in parenthesis are percentages

Table 2 displays demographic and clinical characteristics of couples entered into the study, stratified by TNORCs. No significant differences among the three levels of TNORCs were found in the majority of the variables analyzed. In contrast, women’s age and women’s tobacco smoking displayed a significant rise as TNORCs increased. An increase in TNORCs was also associated with higher incidences of oligo, astheno- and/or teratozoospermia, and cryptozoospermia or azoospermia, and lower percentages of unknown male etiology.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of couples entered into the study, stratified by TNORCs

| Independent variables | TNORC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 691) | 2 (n = 398) | 3 (n = 344) | Pa | Overall (n = 1433) | |

| Women’s age (years) | 34.77 (3.19)b | 35.12 (3.33) | 35.48 (3.17) | 0.003 | 35.04 (3.23) |

| 24–41c | 20–42 | 29–41 | 20–42 | ||

| Women’s body mass index (BMI) | 23.16 (3.94) | 23.35 (3.87) | 23.24 (3.48) | 0.731 | 23.23 (3.81) |

| 15.89–51.78 | 17.51–36.73 | 17.04–35.30 | 15.89–51.78 | ||

| Women’s tobacco smokingd | 3.19 (6.431) | 3.59 (6.41) | 4.38 (7.08) | 0.025 | 3.59 (6.60) |

| 0–25 | 0–20 | 0–25 | 0–25 | ||

| No. of antral follicles | 15.25 (8.68) | 14.94 (8.12) | 13.92 (8.14) | 0.053 | 14.84 (8.41) |

| 1–71 | 3–54 | 3–54 | 1–71 | ||

| Duration of infertility (years) | 2.61 (1.58) | 2.64 (1.57) | 2.81 (1.77) | 0.162 | 2.66 (1.62) |

| 0–14 | 0–10 | 0–13 | 0–14 | ||

| Type of menstrual cycle | 0.382 | ||||

| Regular | 590 (85.4)e | 334 (83.9) | 299 (88.0) | 1223 (85.5) | |

| Irregular | 96 (13.9) | 57 (14.0) | 43 (11.3) | 196 (13.4) | |

| Amenorrhea | 5 (0.7) | 7 (2.1) | 2 (0.7) | 14 (1.1) | |

| Women’s medical conditionf,g | 0.141 | ||||

| Healthy | 535 (77.4) | 291 (73.1) | 250 (72.7) | 1076 (75.1) | |

| Diseased | 156 (22.6) | 107 (26.9) | 94 (27.3) | 357 (24.9) | |

| Men’s medical conditionf,h | 0.903 | ||||

| Healthy | 593 (85.8) | 342 (85.9) | 292 (84.9) | 1227 (85.6) | |

| Diseased | 98 (14.2) | 56 (14.1) | 52 (15.1) | 206 (14.4) | |

| Male infertility etiology | 0.0005 | ||||

| Donor sperm | 18 (2.6) | 7 (1.8) | 5 (1.5) | 30 (2.1) | |

| Oligo-, astheno-, and/or teratozoospermia | 271 (39.2) | 191 (48.0) | 165 (48.0) | 627 (43.8) | |

| Cryptozoospermia or azoospermia | 67 (9.7) | 50 (12.6) | 53 (15.4) | 170 (11.9) | |

| Unknown (normozoospermia) | 335 (48.5) | 150 (37.7) | 121 (35.2) | 606 (42.3) |

aThe adjusted/corrected Benjamini & Hochberg’s significance is P ≤ 0.029, based on 14 statistical tests applied

bValues are crude means and standard deviations in parenthesis

cMinimum and maximum values

dNumber of cigarettes smoked per day for the 3 months before starting the first intended oocyte retrieval cycle

eValues are absolute frequencies and percentages in parenthesis

fMedical conditions were assessed following the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10 Version: 2016). Only ICD-10 chapters with sample sizes ≥ 10 women/men were included in the study as distinct groups. ICD-10 chapters with sample sizes < 10 women/men were combined in a single “catch-all” group called “other diseases” [14]

gICD-10 chapters: “Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism” (n = 23), “Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases” (n = 187), “Mental and behavioral disorders” (n = 17), “Diseases of the nervous system” (n = 22), “Diseases of the circulatory system” (n = 18), “Diseases of the respiratory system” (n = 23), “Diseases of the digestive system” (n = 20), “Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue” (n = 17), and “other diseases” (n = 30)

hICD-10 chapters: “Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases” (n = 33), “Diseases of the circulatory system” (n = 40), “Diseases of the respiratory system” (n = 27), “Diseases of the digestive system” (n = 23), “Diseases of the genitourinary system” (n = 15), and “other diseases” (n = 68)

Table 3 presents the results of the GEE analyses performed to ascertain the effect of TNORCs on five IVF/ICSI outcomes. All the IVF/ICSI outcomes analyzed were significantly impaired as TNORCs increased. In particular, number of cycle cancellations before oocyte retrieval (P ≤ 0.0005) and embryo transfer (P ≤ 0.0005), and number of clinical pregnancy losses (P ≤ 0.0005) significantly rose as TNORCs increased. In contrast, number of clinical pregnancies (P ≤ 0.0005) and LB proportions (P ≤ 0.0005) decreased as TNORCs increased. The women that underwent three TNORCs displayed the worse IVF/ICSI outcomes. Note that the effect of TNORCs on IVF/ICSI outcomes was adjusted for women’s age, women’s tobacco smoking, and male infertility etiology (the three significant variables evidenced in Table 2). Before applying the GEE analyses, the categorical variable “male infertility etiology” was transformed into three dummy variables: “oligo, astheno- and/or teratozoospermia,” “cryptozoospermia or azoospermia,” and “idiopathic male infertility.”

Table 3.

Effect of TNORCs on IVF/ICSI outcomes adjusted for the covariates women’s age, women’s tobacco smoking, and male infertility due to oligo-, astheno-, and/or teratozoospermia, cryptozoospermia or azoospermia, or idiopathic male infertility

| Explanatory variable | IVF/ICSI outcomes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | No. of cycle cancellations before oocyte retrievalb | n | No. of cycle cancellations before embryo transferb | n | No. of clinical pregnanciesb | n | No. of clinical pregnancy lossesb | n | LBc | |

| TNORC | 1433 | P ≤ 0.0005a | 1433 | P ≤ 0.0005 | 1433 | P ≤ 0.0005 | 893 | P ≤ 0.0005 | 1433 | P ≤ 0.0005 |

| 1 | 691 | 0.00 (0.00–0.01)d | 691 | 0.16 (0.12–0.21) | 691 | 0.73 (0.67–0.78) | 493 | 0.03 (0.03–0.05) | 691 | 0.69 (0.63–0.74) |

| 1e | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 398 | 0.12 (0.07–0.22) | 398 | 0.35 (0.27–0.46) | 398 | 0.74 (0.67–0.82) | 261 | 0.16 (0.14–0.19) | 398 | 0.62 (0.56–0.67) |

| 90.13 (14.69–552.89)f | 2.22 (1.95–2.54) | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) | 4.86 (3.59–6.58) | 0.74 (0.66–0.82) | ||||||

| 3 | 344 | 0.19 (0.10–0.37) | 344 | 0.49 (0.43–0.55) | 344 | 0.49 (0.43–0.56) | 139 | 0.44 (0.38–0.50) | 344 | 0.29 (0.25–0.34) |

| 137.84 (23.37–813.12) | 3.07 (2.28–4.13) | 0.67 (0.61–0.73) | 13.07 (9.50–17.99) | 0.19 (0.15–0.24) | ||||||

The covariates appearing in the GEE models are fixed at the following values: women’s age = 35.0349 years; number of cigarettes smoked by women per day for the 3 months before starting the first intended oocyte retrieval cycle = 3.59; oligo-, astheno-, and/or teratozoospermia = 0.44; cryptozoospermia or azoospermia = 0.12; idiopathic male infertility = 0.42

aThe adjusted/corrected Benjamini & Hochberg’s significance is P ≤ 0.05, based on five statistical tests applied

bCount variable that considers cumulative number of events per woman

cBinary variable that takes into account the occurrence = 1 or non-occurrence = 0 of a LB per woman

dValues are marginal means and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis

eReference value

fValues are exponentiated regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis. Note that exponentiated regression coefficients should be interpreted as rate ratios or odds ratios depending on whether a Poissonb or a logisticc regression is applied, respectively [20]

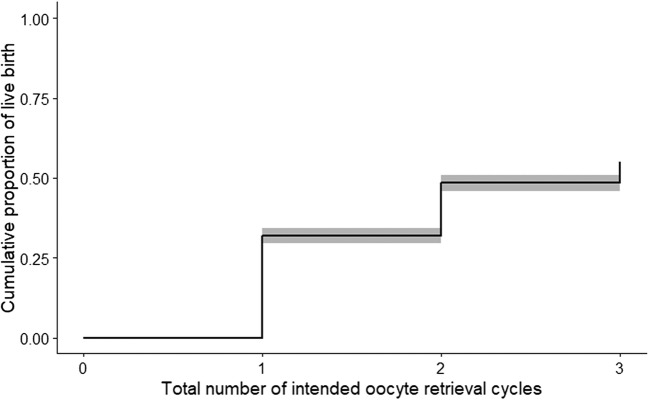

Table 4 shows the cumulative and ORC-specific proportions of LB obtained after applying either a standard or three independent landmark Kaplan Meier survival analyses, respectively. As expected, standard cumulative LB proportions increased from 32% at the end of ORC 1 up to 55% at the end of ORC 3. Figure 1 shows the graphical representation of these data. In contrast, landmark ORC-specific proportions of LB decreased from 32% at the end of ORC 1 to 13% at the end of ORC 3 for those women that had not experienced a LB at the beginning of each ORC.

Table 4.

Cumulative and cycle-specific proportions of LB at each ORC estimated using either a standard or three landmark Kaplan-Meier survival analyses, respectively

| ORC | n | Standard survival analysis | n | Landmark survival analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 458/1433 | 0.32 (0.30–0.34)a | 458/1433 | 0.32 (0.30–0.34) |

| 2 | 694/1433 | 0.48 (0.46–0.51) | 236/975 | 0.24 (0.22–0.27) |

| 3 | 788/1433 | 0.55 (0.52–0.58) | 94/739 | 0.13 (0.10–0.15) |

aValues are proportions and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis

Fig. 1.

Cumulative proportions of LB across three ORCs estimated using a standard Kaplan Meier survival model. The grey band surrounding the Kaplan Meier curve represents the 95% CI

Discussion

The present study shows that whereas cumulative proportions of LB rise, both ORC- and TNORC-specific LB proportions decrease as number of ORCs increase. In addition, women that underwent a total number of two and three ORCs displayed higher incidences of cycle cancellations before either oocyte retrieval or embryo transfer, and clinical pregnancy losses than women that experienced only one ORC. These data indicate that the higher the TNORCs, the lower the women’s fertility and fecundity.

McLernon et al. [7] introduced individualized pre- and post-treatment prediction models of cumulative LB across multiple complete IVF/ICSI cycles. These discrete time logistic regression models have been recently validated in another geographical context and in a more recent time period [21]. Thus, these reports may open the doors to implement these models as counselling tools to inform women about their cumulative probabilities of LB. Actually, McLernon et al. [7] created an online calculator that estimates the cumulative chances of having a baby on the characteristics of the couple and treatment (https://w3.abdn.ac.uk/clsm/opis). The Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) patient predictor also displays cumulative LB probabilities after one, two, and three ORCs, assuming that women have not had prior IVF treatments (https://www.sartcorsonline.com/Predictor/Patient). Although these models may facilitate the women’s decision-making process about pursuing IVF/ICSI treatments before or after one or more unsuccessful attempts, cumulative LB probabilities may incentivize infertile women, specifically those with low or zero fecundity, to have more treatment cycles after one or more unsuccessful attempts. Consequently, they may bias the women’s decision-making process.

Note that we deliberately used non-adjusted, crude estimates of LB when applying the standard and the landmark Kaplan-Meier approaches. We did not adjust for the three covariates (women’s age, women’s tobacco smoking, and male infertility etiology) used in the GEE analyses, or other important predictive covariates. Thus, the non-adjusted estimates of cumulative and ORC-specific LB proportions provided in this study lack any predictive value and, consequently, no predictive inferences can be done based on the present data. The aim of the present study was only to show that cumulative proportions of LB across multiple complete IVF/ICSI cycles follow an inverted pattern to that exhibited by ORC- and TNORC-specific LB proportions. In no case, to build a predictive model for women’s fecundity across multiple complete IVF/ICSI cycles.

It is important to mention that literature supports the notion that the “hazard” or the individual LB probability of each woman within a particular cohort does not remain constant over different treatment cycles. In fact, in mice, repeated superovulation cycles may induce over-expression and over-activation of proteins controlling cell cycle progression in fallopian tubes [22]; alter mitochondrial functions of cumulus cells [23], impair oocyte spindle [23]; and affect ovarian function and decrease the ovarian reserve, fertility, and fecundity [24]. In humans, repeated ovarian stimulation in oocyte donation cycles does not seem to have any adverse effect on number of oocytes collected, oocyte quality, fertilization, preimplantation embryo qualities, and embryo implantation in oocyte recipients [25]. However, repeated superovulation cycles in normal cycling IVF patients may disrupt endometrial physiology [26]. Repeated cycles of hormonal stimulation are also associated with higher women’s depression scores, especially when comparing women with three or more failed treatment cycles versus two unsuccessful treatment cycles [27]. Notwithstanding, literature shows contradicting results about the effect of psychological factors on reproductive outcomes after IVF/ICSI treatment including pregnancy, miscarriage, and LB percentages [28]. Finally, repeated treatment cycles are associated with a progressive increase in women’s age, which may concomitantly decrease the fecundity of women, especially over the age of 35 years [29, 30]. Thus, the decrease in ORC-specific LB proportions in each treatment cycle observed in the present study is not only due to the fact that the most-fecund women are the first in having a LB and then are removed from the initial cohort of infertile women when using a landmark Kaplan-Meier approach (population average decrease in LB proportion). The drop in ORC-specific LB proportions in each treatment cycle is also due to the progressive decrease in women’s fecundity that takes place as number of treatment cycles rises (woman’s-specific decrease in fecundity).

Conclusion

Data from the present study endorse the notion that infertile women should be informed that cumulative LB probabilities exhibit an inverted pattern to that displayed by each individual ORC as well as when grouping together all the ORCs undergone by a woman. The warning issued in the present study is founded on three axioms well established and validated by literature: (1) Cumulative LB probabilities increase as number of ORCs increases; (2) the most-fecund women are the first in becoming pregnant and having a LB, whereas less-fecund women take longer to have a LB or even never experience a LB event; and (3) women’s fecundity is not kept constant across multiple complete IVF/ICSI cycles. It rather steadily decreases as number of treatment cycles increases.

Infertile women should know that the proportion of less-fecund women within the initial cohort of women that starts IVF/ICSI treatment progressively increases as number of treatment cycles rises. In addition, they should know that their individual probability of LB progressively decreases as number of treatment cycles rises. With all this information in hand, infertile women would be in a better position to make decisions about pursuing further IVF/ICSI treatments before or after one or more unsuccessful attempts.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Clinical Investigation, Valencia University Clinical Hospital on November 30th 2017 (2017/316). Written informed consent was not required from the participants because the retrospective nature of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wesselink AK, Rothman KJ, Hatch EE, Mikkelsen EM, Sørensen HT, Wise LA. Age and fecundability in a North American preconception cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:667–e1-667.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, Racowsky C, de Mouzon J, Sokol R, Rienzi L, Sunde A, Schmidt L, Cooke ID, Simpson JL, van der Poel S. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:1786–1801. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malizia BA, Hacker MR, Penzias AS. Cumulative live-birth rates after in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:236–243. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Missmer SA, Pearson KR, Ryan LM, Meeker JD, Cramer DW, Hauser R. Analysis of multiple-cycle data from couples undergoing in vitro fertilization: methodologic issues and statistical approaches. Epidemiology. 2011;22:497–504. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821b5351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luke B, Brown MB, Wantman E, Stern JE, Baker VL, Widra E, Coddington CC, 3rd, Gibbons WE, Ball GD. A prediction model for live birth and multiple births within the first three cycles of assisted reproductive technology. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:744–752. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith ADAC, Tilling K, Nelson SM, Lawlor DA. Live-Birth Rate Associated With Repeat In Vitro Fertilization Treatment Cycles. JAMA. 2015;314:2654–2662. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLernon DJ, Steyerberg EW, Te Velde ER, Lee AJ, Bhattacharya S. Predicting the chances of a live birth after one or more complete cycles of in vitro fertilisation: population based study of linked cycle data from 113 873 women. BMJ. 2016;355:i5735. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modest AM, Wise LA, Fox MP, Weuve J, Penzias AS, Hacker MR. IVF success corrected for drop-out: use of inverse probability weighting. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:2295–2301. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yland J, Messerlian C, Mínguez-Alarcón L, Ford JB, Hauser R, Williams PL, et al. Methodological approaches to analyzing IVF data with multiple cycles. Hum Reprod. 2019;34:549–557. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daya S. Life table (survival) analysis to generate cumulative pregnancy rates in assisted reproduction: are we overestimating our success rates? Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1135–1143. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burks HR, Baker M, Quaas AM, Bendikson KA, Chung K, Paulson RJ. The dilemma of counseling patients about poor prognosis: live birth after IVF with autologous oocytes in a 43-year-old woman with FSH levels above 30 mIU/mL. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:1185–1188. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-0986-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson J, Roberts SA, Vail A. Developments in IVF warrant the adoption of new performance indicators for ART clinics, but do not justify the abandonment of patient-centred measures. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:1155–1159. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MD, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarín JJ, Pascual E, García-Pérez MA, Gómez R, Cano A. Women’s morbid conditions are associated with decreased odds of live birth in the first IVF/ICSI treatment: a retrospective single-center study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:697–708. doi: 10.1007/s10815-019-01401-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cools M, Moons E. Handling Intrahousehold Correlations in Modeling Travel Comparison of Hierarchical Models and Marginal Models. TRR. 2016;2565:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walters E. The P-value and the problem of multiple testing. Reprod BioMed Online. 2016;32:348–349. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan CJ. Landmark analysis: A primer. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019;26:391–393. doi: 10.1007/s12350-019-01624-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 15 November 2018.

- 20.Atkins DC, Baldwin SA, Zheng C, Gallop RJ, Neighbors C. A tutorial on count regression and zero-altered count models for longitudinal substance use data. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27:166–177. doi: 10.1037/a0029508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leijdekkers JA, Eijkemans MJC, van Tilborg TC, Oudshoorn SC, McLernon DJ, Bhattacharya S, Mol BWJ, Broekmans FJM, Torrance HL, OPTIMIST group Predicting the cumulative chance of live birth over multiple complete cycles of in vitro fertilization: an external validation study. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1684–1695. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Nisio V, Rossi G, Palmerini MG, Macchiarelli G, Tiboni GM, Cecconi S. Increased rounds of gonadotropin stimulation have side effects on mouse fallopian tubes and oocytes. Reproduction. 2018;155:245–250. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie JK, Wang Q, Zhang TT, Yin S, Zhang CL, Ge ZJ. Repeated superovulation may affect mitochondrial functions of cumulus cells in mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31368. doi: 10.1038/srep31368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Lai Z, Shi L, Tian Y, Luo A, Xu Z, et al. Repeated superovulation increases the risk of osteoporosis and cardiovascular diseases by accelerating ovarian aging in mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2018;10:1089–1102. doi: 10.18632/aging.101449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul LT, Atilan O, Tulay P. The effect of repeated controlled ovarian stimulation cycles on the gamete and embryo development. Zygote. 2019;27:347–349. doi: 10.1017/S0967199419000418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lahav-Baratz S, Koifman M, Sabo E, Auslender R, Dirnfeld M. p27 and its ubiquitin ligase Skp2 expression in endometrium of IVF patients with repeated hormonal stimulation. Reprod BioMed Online. 2016;32:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beutel M, Kupfer J, Kirchmeyer P, Kehde S, Köhn FM, Schroeder-Printzen I, Gips H, Herrero HJ, Weidner W. Treatment-related stresses and depression in couples undergoing assisted reproductive treatment by IVF or ICSI. Andrologia. 1999;31:27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1999.tb02839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheung C, Saravelos SH, Chan T, Sahota DS, Wang CC, Chung PW, Li TC. A prospective observational study on the stress levels at the time of embryo transfer and pregnancy testing following in vitro fertilisation treatment: a comparison between women with different treatment outcomes. BJOG. 2019;126:271–279. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarín JJ, García-Pérez MA, Cano A. Assisted reproductive technology results: why are live-birth percentages so low? Mol Reprod Dev. 2014;81:568–583. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Assisted reproductive technology (ART). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/art/reports/2016/fertility-clinic.html. Accessed October 1, 2019.