Abstract

Purpose

This systematic review including a meta-analytical approach aims to investigate the safety and efficacy of employing a double ovarian stimulation (DuoStim) and a subsequent double oocyte retrieval in the same menstrual cycle, in poor ovarian reserve (POR) patients.

Methods

A systematic search of literature was performed in the databases of PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Library up until March 2019. Both prospective and retrospective cohort studies considered suitable for inclusion reported on women with POR undergoing a DuoStim in the follicular (FPS) and luteal phase (LPS) of the same menstrual cycle. Following the systematic review of the literature, a meta-analytical approach was attempted.

Results

This study indicates that DuoStim is correlated with a higher number of retrieved oocytes, mature MII oocytes, and good-quality embryos in comparison to conventional stimulation. Additionally, LPS seems to be correlated with an equal or an even higher overall performance in comparison to FPS.

Conclusion

DuoStim favors an enhanced clinical outcome in regard to the total number of yielded oocytes, mature oocytes, and available embryos, along with the quality of obtained embryos. Sourced data indicate that LPS is not correlated with a higher aneuploidy rate. This option may present as promising for the time-sensitive nature of POR patients’ management, by enabling a higher oocyte yield during a single menstrual cycle.

Keywords: Luteal phase stimulation, Follicular phase stimulation, Double stimulation, DuoStim, Poor ovarian response

Introduction

Despite common belief that the female menstrual cycle presents with a single follicular wave, several reports have revealed that more than one wave of follicular recruitment may be observed during the same menstrual cycle [1]. A research published by Baerwald et al. based on serial transvaginal ultrasonography examinations along with hormonal testing in healthy women established the wave-like follicular development during the menstrual cycle, providing solid evidence on the occurrence of such events [2]. The phenomenon of multiple ovarian follicular waves in numerous animal species seems to be consistent with the events observed during the menstrual cycles in humans. Animal studies have provided valuable insight and contributed towards a better understanding of the physiology entailed in this unorthodox phenomenon. The elevation of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels described in domestic animals prior to the recruitment of each follicular wave has also been observed and confirmed in healthy human individuals [3]. Furthermore, inhibin B seems to present with a second unusual peak 2 days following the mid cycle luteinizing hormone (LH) surge, serving as an indicator of a luteal phase follicular development [4]. The involvement of FSH and inhibin B may imply mechanisms associated with follicular waves; however, the all-inclusive process of physiological phenomena has not been fully elucidated yet [5].

Understandably, this new model of folliculogenesis, suggesting the concept that women exhibit two or three waves of folliculogenesis during the same menstrual cycle, opens a new line of investigation on optimal treatment in the context of in vitro fertilization (IVF). Its application in the context of IVF treatment has been further investigated, as a promising step towards optimizing and personalizing the IVF procedure for certain groups of patients. As a result, various studies have developed protocols implementing the phenomenon in ART [6]. In the last decade, research has been published evaluating the potential of luteal phase stimulation either separately or in combination with regular stimulation protocols [7–9]. Thus, the approach of double stimulation (DuoStim) has been suggested implementing conventional follicular phase stimulation (FPS) combined with luteal phase stimulation (LPS) [10]. Overall, the approach of collecting oocytes during the luteal phase has been introduced as beneficial for certain groups of infertile patients, including advanced maternal age patients, or patients with inadequate number of oocytes retrieved during conventional FPS [10]. Benefits associated with this practice may be heightened in patients presenting with poor ovarian response (POR) as well or in cases of urgent fertility preservation for women diagnosed with ovarian cancer scheduled for imminent chemotherapy, oophorectomy, or any gonadotoxic therapy [11, 12].

Hitherto, literature is lacking robust data that may assist clinicians in exploring the concept and safely adopt the practice of luteal phase oocyte retrieval in clinical practice. Guidance on comprehending how this phenomenon could be implemented to enable clinicians’ better practice is imperative. Interestingly, various studies emerging lately explore the value of multiple follicular waves. Reports demonstrate the superiority of the LPS in some cases compared to the standard FPS [13]. On the contrary, early publications indicate that the oocytes retrieved during luteal phase stimulation present with certain “weaknesses” regarding characteristics such as attrition or reduced number of granulosa cells compared to the follicular phase oocytes [14]. Nevertheless, given the fact that performing a second oocyte retrieval during a single menstrual cycle undoubtedly increases the number of recruited oocytes in a shorter timeframe [15], this approach may serve as a valuable asset in the hands of clinicians managing the challenging cases of patients for whom time is of the essence.

This systematic review including a meta-analytical approach, set out to compare the efficacy of LPS versus FPS and subsequent double oocyte retrieval practice under the prism of performing the DuoStim approach within the same menstrual cycle. The rationale behind this study is to determine the role and effectiveness of this method by presenting advantages and disadvantages through a systematic analysis and critical review, along with concurring on the management of POR patients employing this approach. Furthermore, reporting on the value of performing a DuoStim during the same menstrual cycle versus the conventional single follicular phase stimulation (ConStim) is attempted.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

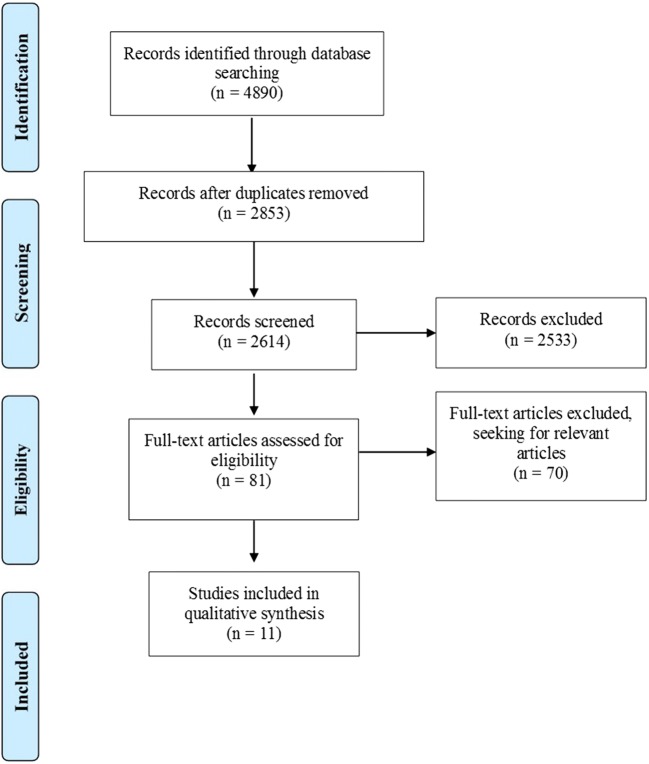

A systematic search of literature was conducted in databases of PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Library, with the aim to elicit full-length articles published in peer-reviewed journals up to the 27th of March 2019. The keywords along with respective combinations that included in the search strategy were “In Vitro Fertilization,” “IVF,” “Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection,” “ICSI,” “Assisted Reproductive Techniques,” “Assisted Reproductive Technologies,” “ART,” “Medically Assisted Reproduction,” “MAR,” “Luteal Phase,” “Double,” “Oocyte Retrieval,” “Egg Retrieval,” “Oocyte Pickup,” “OPU,” “Ovulation,” “Stimulation,” “Follicular Wave,” “DuoStim,” “Dual Stimulation,” “Second Follicular Wave,” and “Lupor.” The preliminary search yielded 4890 studies from the three databases (PubMed/MEDLINE: n = 1401, Embase: n = 2552, Cochrane Central Library: n = 937). From the total yield, 2037 studies were duplicates and thus removed, while 239 studies from the Cochrane database were directly excluded, as they were categorized as reviews (n = 206), protocols (n = 26), editorial (n = 1), and clinical answers (n = 6). The initial screening of titles and abstracts of all records resulted in the removal of 2533 studies, in an attempt to obtain only the relevant articles. Thenceforth, full texts were screened seeking for ultimately relevant articles, along with citation mining that was performed at the reference lists of all included articles to identify other article of relevance. This thorough screening resulted in five prospective studies [6, 9, 10, 16, 17] and six retrospective cohort studies [7, 18–22] that were eligible to be included. In Fig. 1, the flow chart of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) is depicted. Screening and selection of literature was performed independently by three authors (AR, PT, and PG). Any disagreements between the authors were resolved by an arbitration mediated by the senior authors. No protocol was submitted to the Prospero International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), providing details on conducting of this study.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart regarding the search results

Study selection

The authors of the present study opted for including both prospective and retrospective cohort studies that were published in English in peer-reviewed journals. The population comprised of women with POR that underwent ovarian stimulation in the follicular and luteal phase of the same menstrual cycle, during IVF/ICSI cycles. This design served our purpose on concurring on the effectiveness of the DuoStim during the same menstrual cycle, in comparison to the conventional protocol, entailing the employment of a single controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) throughout the follicular phase [23]. Additionally, in this distinct group of patients subjected to DuoStim, we further present associations on embryology and clinical data originating from the comparison of FPS versus LPS.

Excluded studies

Studies employing as a population of interest time-sensitive patients presenting with premature ovarian insufficiency [24] or diagnosed with cancer [25, 26] were excluded from the present study. Other exclusion criteria were on the grounds of performing a double oocyte retrieval in the same menstrual cycle during a natural cycle instead of a stimulation cycle [8]. Moreover, the study of Leahomschi et al. was excluded due to the publication language being Czech [27]. Additionally, following personal communication with the team of Professor Cimadomo, it was elucidated that the two following studies were part of the same project. This led to the decision of including only the data resulting from the multicenter study [10] which was encompassing the data resulting from the smaller intra-patient paired case-control study [28].

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by two authors (EM and SG) based on the selection criteria.

Outcomes

The reported primary outcome measures of interest were number of oocytes retrieved and number of MII oocytes retrieved. The reported secondary outcomes were days of stimulation, cycle cancelation rate, number of cycles with zero MII oocytes retrieved, fertilization rate, blastocyst formation rate, clinical pregnancy rate, miscarriage/early pregnancy loss, and live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate. The authors herein define clinical pregnancy and live birth/ongoing pregnancy rates as the reported respective number per cycle. The miscarriage rate is defined as the number of miscarriages per patients achieving a clinical pregnancy. Comparisons of the above-mentioned outcomes are presented in two arms, the first being FPS versus LPS and the second being the DuoStim protocol versus ConStim only.

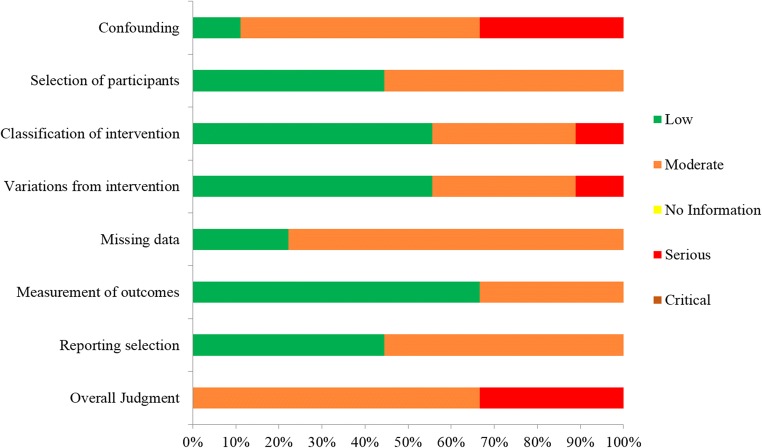

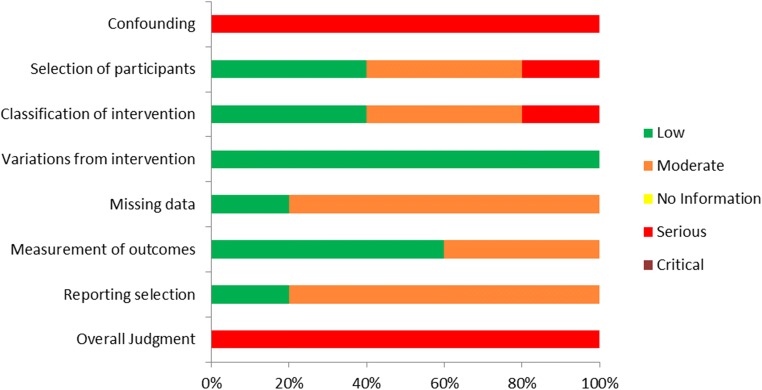

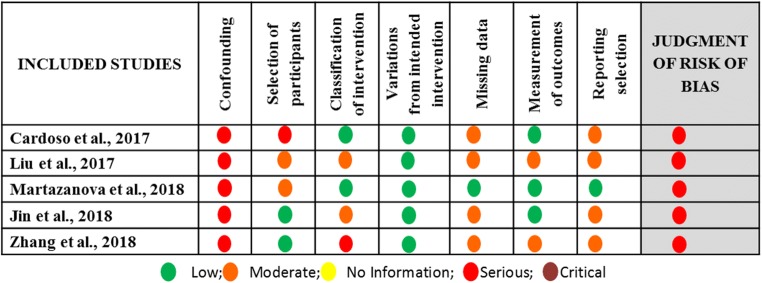

Bias assessment

Assessment of bias was performed on the selected studies regarding (i) confounding, (ii) selection of the participants, (iii) classification of intervention, (iv) variations from intended intervention, (v) missing data, (vi) measurement of outcomes, and (vii) reporting selection. The bias assessment was performed independently by three authors (SG, AR, and EM) employing ROBINS-I tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized interventional studies [29].

Statistical analysis

Following the descriptive presentation of extracted data, a statistical analysis was performed. Statistical comparisons of the above-mentioned outcomes were performed in two arms, the first being FPS versus LPS and the second being the DuoStim protocol versus ConStim. Furthermore, subgroup analysis was performed in both two arms for all of the examined outcomes in regard to the specific patient population that was studied, namely POR subgroup and mixed population subgroup. POR subgroup includes patients diagnosed with POR according strictly to the Bologna criteria and the mixed population subgroup includes patients categorized as POR failing to be categorized according to specific universally accepted criteria. Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) was employed for the analysis of dichotomous data. Odds ratio greater or less than 1 represents a statistically significant difference. Mean difference (MD) with 95%CI was employed regarding the analysis of continuous data. Mean difference greater or less than 0 represents a statistically significant difference. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Either the fixed effect or the random effects model was employed for combining the results according to heterogeneity. Heterogeneity of the exposure effect was evaluated through I2 statistic. An I2 value 80% or greater indicated high heterogeneity and thus the statistical analysis should not be considered as trustworthy, while an I2 value 60% or greater represented significant heterogeneity, leading to the employment of the random effects model. A chi-squared test for heterogeneity was also conducted and the P values are provided. All statistical analysis was performed using the Review Manager (RevMan) software (built 5.3).

Results

Comparison between FPS and LPS regarding IVF/ICSI outcome for patients presenting with a prognosis of POR

Nine studies investigating the efficacy of LPS in patients with a prognosis of POR met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review [6, 7, 9, 10, 16, 19–22]. Four out of nine studies performed a prospective data analysis [6, 9, 10, 16] and the other five were of retrospective nature [7, 19–22]. Data extraction was performed, as presented in the “Materials and methods” section, in order to provide information regarding the studies’ general characteristics and outcomes obtained following FPS and LPS, respectively.

Studies’ general characteristics

Great variation was observed among the studies included in this systematic review regarding the inclusion criteria employed respectively for the selection of the studies’ participants. Four studies included participants characterized as POR patients according to the Bologna criteria [16, 19, 21, 22]. In the other five, different inclusion criteria were employed. In the prospective study of Kuang et al., patients had to meet at least two out of the following five criteria: advanced maternal age defined as over 40 years of age; a history of ovarian surgery; previous IVF attempts using conventional COS protocols that resulted to less than three oocytes; antral follicle count (AFC) of less than five on menstrual cycle days 2–3; and basal serum FSH levels between 10 and 19 IU/L [6]. In the prospective study of Ubaldi et al., patients included had been submitted to preimplantation genetic diagnosis for aneuploidy testing (PGD-A) and had presented with a medical history including: anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels of less than 1.5 ng/mL, AFC of less than six follicles, and/or less than five oocytes retrieved in previous IVF attempts [9]. In the retrospective study of Liu et al., all enrolled patients were 38 years or older, were presenting with normal menstruation, and had at least one follicle 6–11 mm in diameter observed during oocyte retrieval following FPS [20]. In the retrospective study of Rashtian et al., patients had to meet the following inclusion criteria: basal serum FSH levels > 15 IU/m on menstrual cycle day 3; total AFC of less than eight; and at least one failed IVF attempt following conventional COS [7]. In the prospective study of Vaiarelli et al., patients had to meet at least two out of the following four criteria: advanced maternal age defined as over 35 years of age; AMH levels of less than 1.5 ng/mL; AFC of less than six follicles; previous IVF attempts yielding less than five metaphase II (MII) oocytes [10]. Regarding the sample size of this systematic review, a total of 1026 and 988 patients were enrolled in the FPS group and LPS group, respectively. In the FPS group, the number of patients enrolled ranged from 38 to 353, and in the LPS group, the number of patients enrolled ranged from 30 to 366. Data regarding the studies’ general characteristics is presented in Table 1. Assessment of bias was performed and the results are presented in Figs. 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Studies’ general characteristics as obtained following data extraction regarding FPS and LPS respectively

| Studies | Type of study | Infertility etiology | Number of patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPS | LPS | |||

| Kuang et al. 2014 [6] | Prospective | Mixed Populationa | 38 | 30 |

| Ubaldi et al. 2016 [9] | Prospective | Mixed Populationa | 43 | 43 |

| Liu et al. 2017 [20] | Retrospective | Mixed Populationa | 116 | 116 |

| Zhang et al. 2017 [21] | Retrospective | PORb | 153 | 153 |

| Rashtian et al. 2017 [7] | Retrospective | Mixed Populationa | 69 | 69 |

| Jin et al. 2018 [19] | Retrospective | PORb | 72 | 76 |

| Vaiarelli et al. 2018 [10] | Prospective | Mixed Populationa | 353 | 336 |

| Zhang et al. 2018 [22] | Retrospective | PORb | 61 | 61 |

| Madani et al., 2019 [16] | Prospective | PORb | 121 | 104 |

FPS follicular phase stimulation, LPS luteal phase stimulation

aMixed population including patients with a prognosis of poor ovarian response

bPOR population including patients diagnosed with POR according to the Bologna criteria

Fig. 2.

Assessment of risk of bias of studies included in the systematic review regarding FPS vs LPS arm

Fig. 3.

Summary of risk of bias assessment regarding each item for each study included in the systematic review regarding FPS vs LPS arm

Stimulation protocols employed

Heterogeneity was also observed among the studies regarding the stimulation protocols employed for both FPS and LPS, respectively. In the great majority of the studies, FPS was achieved via the employment of mild and minimal stimulation protocols based on citrate clomiphene (CC) and letrozole administration. In some of the studies, exogenous gonadotropin administration was also employed in order to further support follicular development. Human menopausal gonadotropin (HMG) and recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (rFSH) and luteinizing hormone (rLH) are presented to have been used. In some of the studies, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist was used as a part of the standard protocol employed and in some others was used only if was necessary in order to prevent early LH surge. Regarding LPS, similar protocols to FPS were used. In order to induce ovulation, different approaches among the studies were used including administration of triptorelin, buserelin, recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin (rHCG), GnRH agonist, and GnRH antagonist. Extracted data regarding the stimulation protocols employed are presented in Table 2. Seven studies reported results comparing the total dose of exogenous gonadotropins required for FPS and LPS, respectively [6, 7, 16, 19–22]. In three out of seven studies, a statistically significant higher dose of HMG was required for LPS in comparison to FPS [6, 7, 16]. Similarly, in the study of Zhang et al., a higher dose of gonadotropins was required for LPS in comparison to FPS. However, three studies reported no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the dose of exogenous gonadotropins required for stimulation in each phase [7, 19, 20]. Variation was also observed among the studies regarding the initiation time of LPS protocol. Initiation of LPS protocol ranges among the studies between 0 and 7 days following first oocyte retrieval. Moreover, different criteria were used among the studies regarding the number and the size of pre-existing small follicles required for LPS. This size ranges among the studies between 2 and 11 mm. The aforementioned data are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Extracted data regarding the stimulation protocols employed for FPS and LPS respectively

| Studies | Stimulation protocols employed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPS | First trigger | Pre-existing follicles required for LPS | Initiation of LPS (days following 1st OR) | LPS | Second trigger | |

| Kuang et al. 2014 [6] | CC, Let, HMG | GnRH-ag, Ibup | At least 2 antral follicles 2–8 mm | 0–1 days | Let, HMG, Medrox | GnRH-ag, Ibup |

| Ubaldi et al. 2016 [9] | rFSH, rLH, GnRH-antag | Bus | NA | 5 days | rFSH, rLH, GnRH-antag | Bus |

| Liu et al. 2017 [20] | rFSH, rLH | rHCG | At least one antral follicle 6–11 mm | 1–3 days | HMG | rHCG |

| Zhang et al. 2017 [21] | CC, Gon | GnRH-ag | Antral follicles 5–10 mm | 1 day | Gon | rHCG |

| Rashtian et al. 2017 [7] | Let, CC, Gon, GnRH-antag | GnRH-ag | At least 1 antral follicle < 11 mm | 1 day | Let, CC, Gon | rHCG |

| Jin et al. 2018 [19] | Let or CC, HMG, GnRH-antag | GnRH-ag | NA | 1–3 days | CC, HMG | rHCG |

| Vaiarelli et al. 2018 [10] | E2 valerate, rFSH, rLH, GnRH-antag | Bus | NA | 5 days | rFSH, rLH, GnRH-antag | Bus |

| Zhang et al. 2018 [22] | CC, HMG | rHCG | At least 2 antral follicles 2–8 mm | 2–7 days | CC, HMG | rHCG |

| Madani et al. 2019 [16] | CC, Let, HMG | Bus, Ibup | At least 2 antral follicles 2–8 mm | 1 day | Let, HMG | Bus |

FPS follicular phase stimulation, LPS luteal phase stimulation, OR oocyte retrieval, CC clomiphene citrate, HMG human menopausal gonadotropin, rFSH recombinant FSH, rLH recombinant LH, rHCG recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin, Gon exogenous gonadotropins, GnRH-ag GnRH agonist, GnRH-antag GnRH antagonist, Bus buserelin, Ibup ibuprofen, Let letrozole, Medrox medroxyprogesterone acetate, NA not applicable

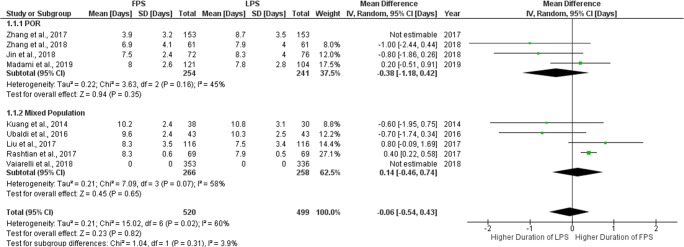

Stimulation days

Regarding the length of the stimulation period required for FPS and LPS, respectively, eight studies reported results comparing the days of stimulation for each group [6, 7, 9, 10, 16, 19–22]. Stimulation duration ranged from 3.9 to 10.2 days during FPS and from 8.7 to 10.8 days during LPS. Only two studies reported a statistically significant higher number of stimulation days during LPS [21, 22] compared to FPS. The remaining six studies did not report any statistically significant difference. Extracted data regarding days of stimulation are presented in Table 3. Seven studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing days of stimulation between FPS and LPS. In the study of Zhang et al., data provided regarding the stimulation period refer only in the duration of gonadotropin administration and not in the duration of the total stimulation protocol, and thus, this study was excluded from the analysis [21]. Total heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 60%, P value < 0.02); thus, the random effects model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (MD = − 0.06, 95%CI = − 0.54, 0.43) between FPS and LPS regarding days of stimulation. Following subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in any of the two subgroups. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 4.

Table 3.

Extracted data regarding duration of stimulation and cycle cancelation rate for FPS and LPS respectively

| Studies | Stimulation days | Cycle cancelation rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPS | LPS | FPS | LPS | |

| Kuang et al. 2014 [6] | 10.2 ± 2.4 | 10.8 ± 3.1 | 20/38 (52.6%) | 13/30 (43.3%) |

| Ubaldi et al. 2016 [9] | 9.6 ± 2.4 | 10.3 ± 2.5 | 4/43 (9.3%) | 3/43 (6.9%) |

| Liu et al. 2017 [20] | 8.3 ± 3.5 | 7.5 ± 3.4 | 43/116 (37.1%) | 33/116 (28.4%) |

| Zhang et al. 2017 [21] | 3.9 ± 3.2 | 8.7 ± 3.5 | 19/153 (12.4%) | 5/153 (3.3%) |

| Rashtian et al. 2017 [7] | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 7.9 ± 0.5 | ΝΑ | ΝΑ |

| Jin et al. 2018 [19] | 7.5 ± 2.4 | 8.3 ± 4.0 | 25/72 (34.7%) | 21/76 (27.6%) |

| Vaiarelli et al. 2018 [10] | NA | NA | 17/353 (4.8%) | 26/336 (7.7%) |

| Zhang et al. 2018 [22] | 6.9 ± 4.1 | 7.9 ± 4.0 | NA | NA |

| Madani et al. 2019 [16] | 8.0 ± 2.6 | 7.8 ± 2.8 | 12/121 (9.9%) | 23/104 (22.1%) |

FPS follicular phase stimulation, LPS luteal phase stimulation, NA not applicable

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of days of stimulation resulting from the comparison of FPS and LPS respectively

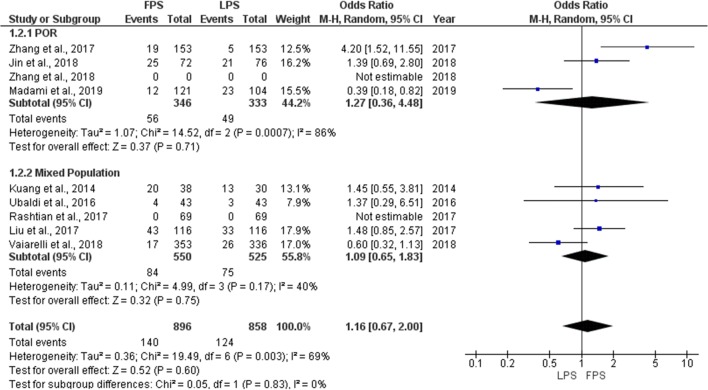

Cycle cancelation rate

Seven studies reported results comparing the cycle cancelation rate for each phase [6, 9, 10, 16, 19–21]. Four were of prospective nature and the other three of retrospective. Cycle cancelation rate ranged from 4.8 to 52.6% during FPS and from 3.3 to 43.3% during LPS. No statistically significant difference was observed between the two stimulation phases in any of the studies regarding cycle cancelation rate. Extracted data regarding cycle cancelation rate are presented in Table 3. Total heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 69%, P value = 0.002); thus, the random effects model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (OR = 1.16, 95%CI = 0.67, 2.00) between FPS and LPS regarding the cycle cancelation rate. Following subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in any of the two subgroups. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of cycle cancelation rate resulting from the comparison of FPS and LPS respectively

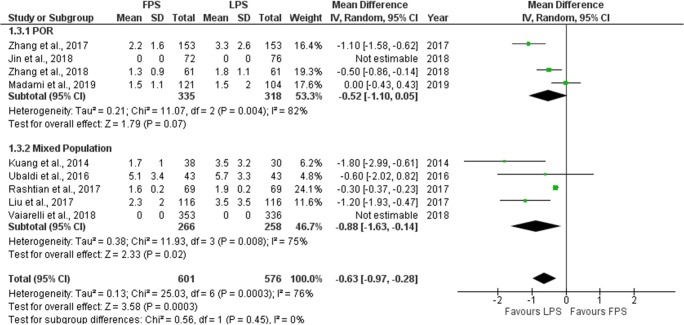

Number of oocytes retrieved

Eight studies reported results comparing the number of oocytes retrieved in each phase [6, 7, 9, 16, 19–22]. Three were of prospective nature and the other five of retrospective. Mean number of oocytes retrieved ranged from 1.5 to 5.1 in FPS and from 1.3 to 5.7 in LPS. One study reported results as a median and range [19]. Five studies reported a statistically significant higher oocyte yield during LPS [6, 19–22]. The remaining three studies presented with no statistically significant differences regarding the number of oocytes retrieved [7, 9, 16]. Extracted data regarding number of oocytes retrieved are presented in Table 4. Seven studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing the number of oocytes retrieved between FPS and LPS. The study in which results reported as a median and range was excluded from the statistical analysis [19]. Total heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 76%, P value = 0.0003); thus, the random effects model was employed. Pooled data analysis revealed a statistically significant higher mean number of retrieved oocytes following LPS in comparison to FPS (MD = − 0.63, 95%CI = − 0.97, − 0.28). Following subgroup analysis, a statistically significant higher mean number of retrieved oocytes was observed following LPS in comparison to FPS (MD = − 0.88, 95%CI = − 1.63, − 0.14) in the mixed population subgroup. In the POR subgroup, a higher number of retrieved oocytes was also observed following LPS, but a statistically significant difference could not be established marginally (MD = − 0.52, 95%CI = − 1.10, 0.05). Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 6.

Table 4.

Extracted data regarding the number of oocytes retrieved and the number of MII oocytes obtained following FPS and LPS respectively

| Studies | Number of oocytes retrieved | Number of MII oocytes | MII oocyte ratea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPS | LPS | FPS | LPS | FPS | LPS | |

| Kuang et al. 2014 [6] | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 3.5 ± 3.2 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 2.7 ± 2.7 | 53/62 (85.5%) | 82/105 (78.1%) |

| Ubaldi et al. 2016 [9] | 5.1 ± 3.4 | 5.7 ± 3.3 | 3.4 ± 1.9 | 4.1 ± 2.5 | ΝΑ | ΝΑ |

| Liu et al. 2017 [20] | 2.3 ± 2.0 | 3.5 ± 3.5 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 2.8 ± 3.1 | ΝΑ | ΝΑ |

| Zhang et al. 2017 [21] | 2.2 ± 1.6 | 3.3 ± 2.6 | 2.03 ± 1.53 | 3.16 ± 2.55 | 311/333 (93.4%) | 483/499 (96.8%) |

| Rashtian et al. 2017 [7] | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | ΝΑ | ΝΑ |

| Jin et al. 2018 [19] | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–4) | ΝΑ | ΝΑ | 25/35 (71.4%) | 46/58 (79.3%) |

| Vaiarelli et al. 2018 [10] | NA | NA | 4.0 ± 2.5 | 4.7 ± 3.0 | ΝΑ | ΝΑ |

| Zhang et al. 2018 [22] | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | NA | NA | 325/416 (78.1%) | 374/551 (67.9%) |

| Madani et al. 2019 [16] | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 2 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 1.6 | NA | NA |

FPS follicular phase stimulation, LPS luteal phase stimulation, NA not applicable

aMII oocytes per number of total oocytes obtained following oocyte retrieval

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of number of oocytes retrieved resulting from the comparison of FPS and LPS respectively

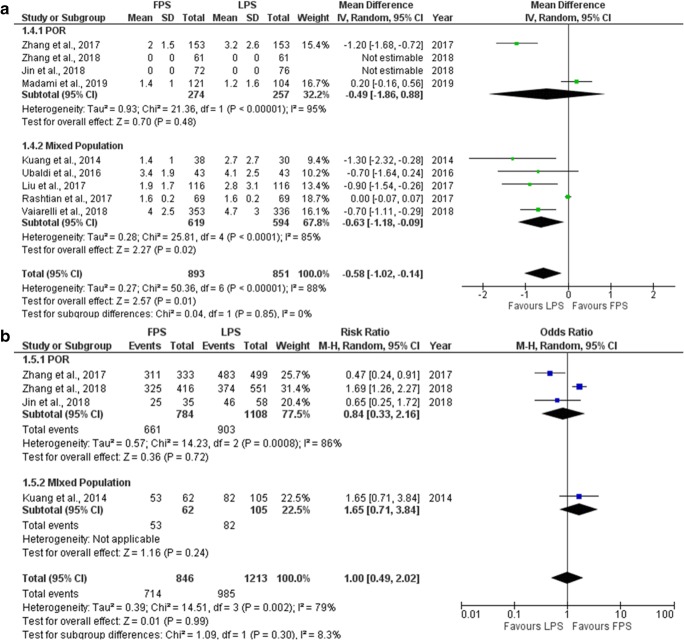

Number of metaphase II oocytes

Nine studies reported results regarding the number of MII oocytes retrieved in each phase. Four out of nine studies included performed a prospective data analysis [6, 9, 10, 16] and the other five were of retrospective nature [7, 19–22]. Five studies presented their results in the format of mean number of MII oocytes retrieved, two studies in the format of MII retrieval rate and two studies in both formats. Mean number of MII oocytes retrieved ranged from 1.4 to 4.0 regarding FPS and from 1.2 to 4.7 regarding LPS. MII oocyte rate per number of total oocytes obtained following oocyte retrieval ranged from 71.4 to 93.4% regarding FPS and from 67.9 to 96.8% regarding LPS. Four out of nine studies reported a statistically significant higher number of MII oocytes retrieved during LPS [6, 10, 20, 21], and one reported a statistically significant higher number of MII oocytes retrieved during FPS [22], whereas the remaining four reported no statistically significant difference [7, 9, 16, 19]. Extracted data regarding number of MII oocytes obtained are presented in Table 4. Seven studies included in the statistical analysis comparing the mean number of MII oocytes retrieved between FPS and LPS. Total heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 88%, P value < 0.001); thus, the random effects model was employed. Pooled data analysis revealed a statistically significant higher mean number of MII oocytes retrieved following LPS in comparison to FPS (MD = − 0.58, 95%CI = − 1.02, − 0.14). Following subgroup analysis, a statistically significant higher mean number of retrieved MII oocytes was observed following LPS in comparison to FPS (MD = − 0.63, 95%CI = 1.18, − 0.09) in the mixed population subgroup. In the POR subgroup, no statistically significant difference was established (Fig. 7a). Four studies included in the statistical analysis comparing the MII oocyte rate between FPS and LPS. Total heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 79%, P value = 0.002); thus, the random effects model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (OR = 1.00, 95%CI = 0.49, 2.02) between FPS and LPS regarding the MII oocyte rate. Following subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in any of the two subgroups (Fig. 7b). Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Forest plot regarding the number of MII oocytes obtained resulting from the comparison of FPS and LPS respectively. a Comparison of mean difference of MII oocytes. b Comparison of MII oocyte rate

Embryology data

Great variation was observed among the studies regarding the criteria used to evaluate the embryology data obtained following FPS and LPS respectively. In the study of Kuang et al., no statistically significant difference was established between the two phases regarding the number of top-quality embryos, the number of cryopreserved embryos, and the cleavage rate defined as the number of fertilized zygotes reaching cleavage stage. In the same study, a statistically significant higher number of cleaved embryos was observed in the LPS group probably due to the higher number of fertilized oocytes obtained in this group [6]. In the study of Ubaldi et al., no statistically significant difference was observed between FPS and LPS in regard to the number of fertilized oocytes, the number of biopsied blastocysts, the number of euploid blastocysts, the blastocyst quality, the type of aneuploidy, and the day of blastocyst formation [9]. In the study of Liu et al., a statistically significant increased number of fertilized oocytes, number of cleaved embryos, and number of top-quality embryos were observed in the LPS group. No statistically significant difference could be established in regard to the top-quality embryos rate, the embryo survival rate, and the number of cryopreserved embryos between the two stimulation phases [20]. A statistically significant higher mean number of 2 pro-nuclei (2PN) zygotes and mean number of good-quality embryos was observed in the study of Zhang et al. in the LPS group [21]. In the study of Vaiarelli et al., a higher number of fertilized oocytes and blastocysts were observed in the LPS group as a result of the higher number of MII oocytes collected in this group. No statistically significant difference was observed between the two phases in regard to the mean number of euploid blastocysts obtained. The mean fertilization, blastocyst, and euploid blastocyst rates, calculated per number of MII oocytes collected, did not differ significantly between the two phases. Similarly, the overall fertilization, blastocyst, and euploid blastocyst rates of the MII oocytes obtained following FPS and LPS, respectively, did not differ significantly [10]. No statistically significant difference was observed between FPS and LPS in terms of the cleavage rate and the top-quality embryo rate in the study of Zhang et al. [22].

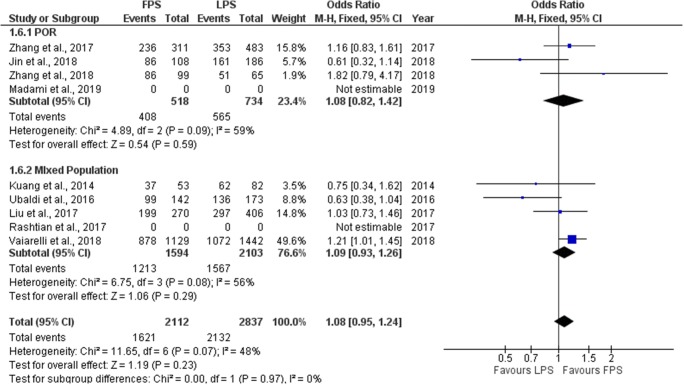

Fertilization rate

Seven studies reported results regarding the fertilization rate observed in each phase. Fertilization rate is defined as the number of 2PN zygotes obtained per inseminated oocytes. Three out of seven studies included performed a prospective data analysis [6, 9, 10] and the other four were of retrospective nature [19–22]. Fertilization rate ranged from 69.7 to 86.9% regarding FPS and from 73.1 to 86.5% regarding LPS. No statistically significant difference was observed between FPS and LPS in neither of the studies regarding fertilization rate. Extracted data regarding fertilization rate observed among the studies are presented in Table 5. Seven studies included in the statistical analysis comparing fertilization rate between FPS and LPS. Total heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 48%, P value = 0.07); thus, the fixed effect model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (OR = 1.08, 95%CI = 0.95, 1.24) between FPS and LPS regarding fertilization rate. Following subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in any of the two subgroups. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 8.

Table 5.

Extracted data regarding fertilization rate and clinical pregnancy rate observed following FPS and LPS respectively

| Studies | Fertilization ratea | Clinical pregnancy rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPS | LPS | FPS | LPS | |

| Kuang et al. 2014 [6] | 37/53 (69.8%) | 62/82 (75.6%) | 8/13 (61.5%) | 5/7 (71.4%) |

| Ubaldi et al. 2016 [9] | 99/142 (69.7%) | 136/173 (78.6%) | 6/7 (85.7%) | 6/8 (75%) |

| Liu et al., 2017 [20] | 199/270 (73.7%) | 297/406 (73.1%) | 4/16 (25%) | 7/34 (20.6%) |

| Zhang et al. 2017 [21] | 236/311 (75.8%) | 353/483 (73.1%) | 3/28 (10.7%) | 14/36 (38.9%) |

| Rashtian et al. 2017 [7] | ΝΑ | ΝΑ | ΝΑ | ΝΑ |

| Jin et al. 2018 [19] | 86/108 (79.6%) | 161/186 (86.5%) | 7/20 (35.0%) | 12/32 (37.5%) |

| Vaiarelli et al. 2018 [10] | 878/1129 (71.4%) | 1072/1442 (74.3%) | 36/81 (44.4%) | 45/83 (54.2%) |

| Zhang et al. 2018 [22] | 86/99 (86.9%) | 51/65 (78.5%) | 4/29 (13.8%) | 3/14 (21.4%) |

| Madani et al. 2019 [16] | NA | NA | NA | NA |

FPS follicular phase stimulation, LPS luteal phase stimulation, NA not applicable

a:Fertilization rate defined as the number of 2PN zygotes obtained per inseminated oocytes

Fig. 8.

Forest plot of fertilization rate resulting from the comparison of FPS and LPS respectively

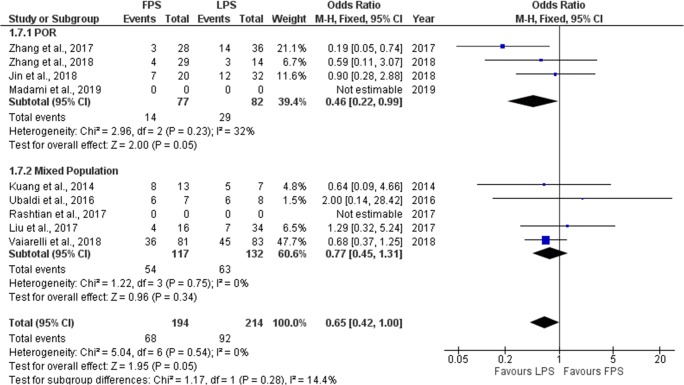

Clinical pregnancy rate

Seven studies reported results regarding the clinical pregnancy rate (CP) observed in each phase. Three out of the seven studies included performed a prospective data analysis [6, 9, 10] and the other four were of retrospective nature [19–22]. CP rate ranged from 10.7 to 85.7% regarding FPS and from 20.6 to 75% regarding LPS. No statistically significant difference was observed between FPS and LPS in six of the studies regarding CP. In the study of Zhang et al., a statistically higher CP rate observed in the LPS phase [21]. Extracted data regarding CP rate observed among the studies are presented in Table 5. Seven studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing clinical pregnancy rate between FPS and LPS. Total heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P value = 0.54); thus, the fixed effect model was employed. Pooled data analysis revealed a trend towards a statistically significant higher clinical pregnancy rate following LPS in comparison to FPS (OR = 0.65, 95%CI = 0.42, 1.00). Following subgroup analysis, a statistically significant higher clinical pregnancy rate was observed following LPS in comparison to FPS in the POR subgroup (OR = 0.46, 95%CI = 0.22, 0.99). In the mixed population subgroup, no statistically significant difference could be established between FPS and LPS. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Forest plot of clinical pregnancy rate resulting from the comparison of FPS and LPS respectively

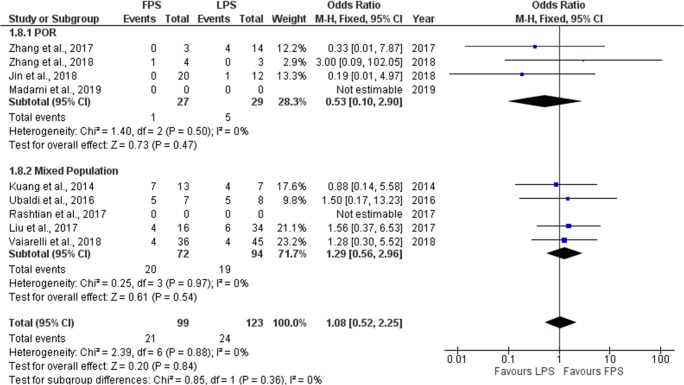

Live birth rate/ongoing pregnancy rate

Seven studies reported results regarding the live birth rate/ongoing pregnancy rate (LB/OP) observed in each stimulation phase. Three out of the seven studies included performed a prospective data analysis [6, 9, 10] and the other four were of retrospective nature [19–22]. LB/OP rate ranged from 10.3 to 71.4% regarding FPS and from 14.3 to 62.5% regarding LPS. No statistically significant difference was observed between FPS and LPS in six of the studies regarding LB/OP. In the study of Zhang et al., a statistically higher LB/OP rate was observed in the LPS phase [21]. Extracted data regarding CP rate observed among the studies are presented in Table 6. Seven studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing LB/OP rate between FPS and LPS. Total heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P value = 0.88); thus, the fixed effect model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (OR = 1.08, 95%CI = 0.52, 2.25) between FPS and LPS regarding fertilization rate. Following subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in any of the two subgroups. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 10.

Table 6.

Extracted data regarding live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate and miscarriage/early pregnancy loss rate observed following FPS and LPS respectively

| Studies | Live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate | Miscarriage/early pregnancy loss rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPS | LPS | FPS | LPS | |

| Kuang et al. 2014 [6] | 7/13 (53.8%) | 4/7 (57.1%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 1/5 (20%) |

| Ubaldi et al. 2016 [9] | 5/7 (71.4%) | 5/8 (62.5%) | 1/6 (16.7%) | 1/6 (16.7%) |

| Liu et al. 2017 [20] | 4/16 (25%) | 6/34 (17.6%) | 0/4 (0%) | 1/7 (14.3%) |

| Zhang et al. 2017 [21] | 3/28 (10.7%) | 10/36 (27.7%) | 0/3 (0%) | 4/14 (28.6%) |

| Rashtian et al. 2017 [7] | ΝΑ | ΝΑ | ΝΑ | ΝΑ |

| Jin et al. 2018 [19] | 7/20 (35.0%) | 11/32 (34%) | 0/20 (0%) | 1/12 (8.3%) |

| Vaiarelli et al. 2018 [10] | 32/81 (39.5%) | 41/83 (49.4%) | 4/36 (11.1%) | 4/45 (8.9%) |

| Zhang et al. 2018 [22] | 3/29 (10.3%) | 2/14 (14.3%) | 1/4 (25%) | 0/3 (0%) |

| Madani et al. 2019 [16] | NA | NA | NA | NA |

FPS follicular phase stimulation, LPS luteal phase stimulation, NA not applicable

Fig. 10.

Forest plot of live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate resulting from the comparison of FPS and LPS respectively

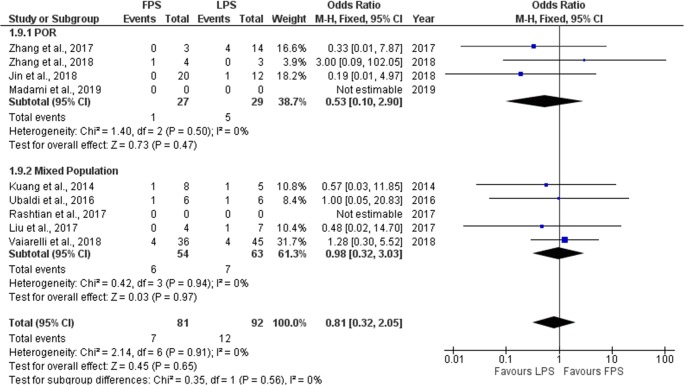

Miscarriage rate/early pregnancy loss

Seven studies reported results regarding the miscarriage rate/early pregnancy loss rate (M/EPL) observed in each stimulation phase. Three out of the seven studies included, performed a prospective data analysis [6, 9, 10] and the other four were of retrospective nature [19–22]. M/EPL rate ranged from 0 to 25% regarding FPS and from 0 to 20% regarding LPS. No statistically significant difference was observed between FPS and LPS in six of the studies regarding M/EPL. In the study of Zhang et al., a statistically higher M/EPL rate observed in the LPS phase [21]. Extracted data regarding M/EPL rate observed among the studies are presented in Table 6. Seven studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing M/EPL rate between FPS and LPS. Total heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P value = 0.91); thus, the fixed effect model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (OR = 0.81, 95%CI = 0.32, 2.05) between FPS and LPS regarding fertilization rate. Following subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in any of the two subgroups. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Forest plot of miscarriage/early pregnancy loss rate resulting from the comparison of FPS and LPS respectively

Number of cycles leading to no oocytes retrieved

Five studies reported on number of cycles leading to no oocytes retrieved for each stimulation phase. Four out of seven studies included performed a prospective data analysis [6, 9, 10, 16] and the last one was of retrospective nature [16]. In the study of Zhang et al., a statistically significant higher number of cycles leading to no oocytes retrieved was observed in the FPS phase in comparison to LPS phase (12.4% vs 3.3%, respectively) [21]. In the study of Madani et al., a statistically significant higher number of cycles leading to no oocytes retrieved was observed in the LPS phase in comparison to FPS phase (16.3% vs 10.7%, respectively) [16]. No statistically significant difference was reported in neither of the other three studies regarding the number of cycles leading to no oocytes retrieved.

Comparison between DuoStim and ConStim regarding IVF/ICSI outcome for patients presenting with a prognosis of POR

Five studies investigating the efficacy of double ovarian stimulation (DuoStim) in patients with a prognosis of POR, met the inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review [17–20, 22]. Four out of the five studies included performed a retrospective data analysis [18–20, 22] and the last one was of prospective nature [17]. Data extraction was performed, as presented in the “Materials and methods” section, in order to provide information regarding the studies’ general characteristics and outcomes obtained following DuoStim and ConStim, respectively.

Studies’ general characteristics

Great variation was observed among the studies included, regarding the inclusion criteria employed for the selection of the studies’ participants. In two studies, included participants were characterized as POR patients according to the Bologna criteria [19, 22]. In the other three, different inclusion criteria were set. In the prospective study of Martazanova et al., patients had to meet the following criteria: age < 43 years, AFC of less than six, and basal serum FSH levels up to 11 IU/mL [17]. In the retrospective study of Cardoso et al., no specific inclusion criteria were set [18]. In the retrospective study of Liu et al., all enrolled patients were 38 years or older, were presenting normal menstruation, and had at least one follicle 6–11 mm in diameter observed during oocyte retrieval following FPS [20]. Regarding the sample size of this systematic review, a total of 342 and 412 patients were enrolled in the DuoStim group and ConStim group respectively. In the DuoStim group, the number of patients enrolled ranged from 13 to 116 patients, and in the ConStim group, the number of patients enrolled ranged from 13 to 132. Data regarding studies’ general characteristics are presented in Table 7. Assessment of bias was performed and the results are presented in Figs. 12 and 13.

Table 7.

Studies’ general characteristics as obtained following data extraction regarding DuoStim and ConStim respectively

| Studies | Type of study | Infertility etiology | Number of patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DuoStim | ConStim | |||

| Cardoso et al., 2017 [18] | Retrospective | Mixed populationa | 13 | 13 |

| Liu et al. 2017 [20] | Retrospective | Mixed populationa | 116 | 116 |

| Martazanova et al. 2018 [17] | Prospective | Mixed populationa | 76 | 72 |

| Jin et al. 2018 [19] | Retrospective | PORb | 76 | 132 |

| Zhang et al. 2018 [22] | Retrospective | PORb | 61 | 79 |

DuoStim double ovarian stimulation, ConStim conventional ovarian stimulation

aMixed population including patients with a prognosis of poor ovarian response

bPOR population including patients diagnosed with POR according to the Bologna criteria

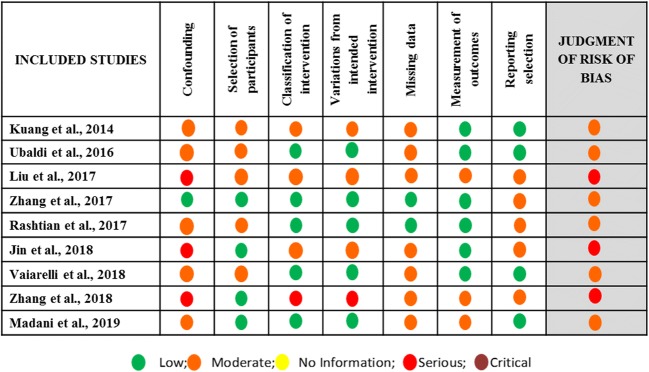

Fig. 12.

Assessment of risk of bias of studies included in the systematic review regarding DuoStim vs ConStim arm

Fig. 13.

Summary of risk of bias assessment regarding each item for each study included in the systematic review regarding DuoStim vs ConStim arm

Stimulation protocols employed

Variation was also observed among the studies regarding stimulation protocols employed for both DuoStim and ConStim, respectively. In the study of Cardoso et al., the protocol of choice for ConStim was the GnRH antagonist protocol. The protocol included HMG and recombinant follitropin alpha (rFSH) administration. Daily administration of GnRH antagonist started when a follicle reached 14 mm in diameter. When at least three follicles reached 16 mm in diameter, ovulation was induced via rHCG administration. Five days following the first oocyte retrieval, luteal phase stimulation was initiated to perform a DuoStim. The stimulation protocol employed in the luteal phase was the same as the conventional protocol. Ovulation for the second oocyte retrieval was induced via GnRH agonist administration [18]. In the study of Martazanova et al., no data were presented regarding the stimulation protocol employed [17]. Stimulation protocol data recorded in the studies of Liu et al., Jin et al., and Zhang et al. are presented in Table 2. One study reported results comparing the total dose of exogenous gonadotropins required for DuoStim and ConStim, respectively [20]. According to this study, a twofold higher dose of gonadotropins was required for DuoStim in comparison to ConStim [20].

Stimulation days

Regarding the stimulation period required for DuoStim and ConStim respectively, only one study reported results comparing the days of stimulation for each group [20]. The mean duration of DuoStim was 15.26 ± 4.90 days, and the mean duration of ConStim was 8.26 ± 3.52. This difference reached statistical significance.

Cycle cancelation rate

Two studies reported results comparing the cycle cancelation rate between DuoStim and ConStim [19, 20]. Cycle cancelation rate ranged from 13.1 to 18.10% in the DuoStim and from 28.7 to 37.1% in the ConStim. In both studies, a statistically significant higher cycle cancelation rate observed in the ConStim group in comparison to DuoStim group (37.1% vs 18.10% and 28.7% vs 13.1%, respectively).

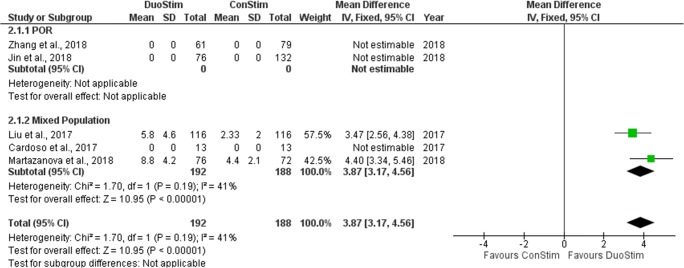

Number of oocytes retrieved

Four studies reported results comparing the number of oocytes retrieved following DuoStim and ConStim, respectively [17–20]. Three were of retrospective nature [18–20] and in the last one a prospective data analysis was performed [17]. Mean number of oocytes retrieved ranged from 5.83 to 8.8 in the DuoStim group and from 2.3 to 6.7 in the ConStim group. Two studies reported results as a median and range [18, 19]. All of these studies reported a statistically significant higher number of oocytes retrieved following DuoStim in comparison to ConStim. Extracted data regarding number of oocyte retrieved are presented in Table 8. Two studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing the mean number of oocytes retrieved between DuoStim and ConStim. The studies in which results reported as a median and range were excluded from the statistical analysis [18, 19]. Total heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 41%, P value = 0.19); thus, the fixed effect model was employed. Pooled data analysis revealed a statistically significant higher mean number of retrieved oocytes following DuoStim in comparison to ConStim (MD = 3.87, 95%CI = 3.17, 4.56). Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 14.

Table 8.

Extracted data regarding the number of oocytes retrieved and the number of MII oocytes obtained following DuoStim and ConStim respectively

| Studies | Number of oocytes retrieved | Number of MII oocytes | MII oocyte ratea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DuoStim | ConStim | DuoStim | ConStim | DuoStim | ConStim | |

| Cardoso et al. 2017 [18] | 11.7 (1–28) | 6.7 (2–13) | 9.23 (1–25) | 5.3 (2–11) | NA | NA |

| Liu et al. 2017 [20] | 5.83 ± 4.60 | 2.33 ± 1.99 | 4.73 ± 4.01 | 1.93 ± 1.70 | NA | NA |

| Martazanova et al. 2018 [17] | 8.8 ± 4.2 | 4.4 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 3.6 | 3.9 ± 2.0 | NA | NA |

| Jin et al., 2018 [19] | 4 (3–5) | 2 (1–4) | NA | NA | 71/93 (76.3%) | 143/165 (86.7%) |

| Zhang et al. 2018 [22] | NA | 2.4 ± 1.5 | NA | NA | 129/164 (78.6%) | 374/551 (67.9%) |

DuoStim double ovarian stimulation, ConStim conventional ovarian stimulation, NA not applicable

aMII to oocytes per number of total oocytes obtained following oocyte retrieval

Fig. 14.

Forest plot of number of oocytes retrieved resulting from the comparison of DuoStim and ConStim respectively

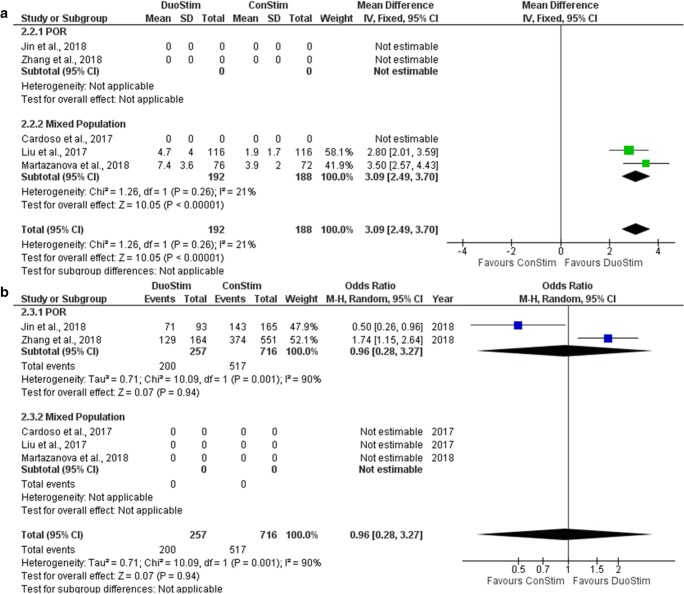

Number of metaphase II oocytes

Five studies reported results regarding the number of MII oocytes retrieved following DuoStim and ConStim, respectively [17–20, 22]. Four out of five studies included performed a retrospective data analysis [18–20, 22] and the other one was of prospective nature [17]. Three studies presented results in the format of mean number of MII oocytes retrieved and two studies in the format of MII Oocyte retrieval rate. Mean number of MII oocytes retrieved ranged from 4.73 to 9.23 following DuoStim and from 1.93 to 5.3 following ConStim. MII oocyte rate ranged from 78.6 to 76.3% following DuoStim and from 67.9 to 86.7% following ConStim. Three out of the five studies reported a statistically significant higher mean number of MII oocytes retrieved during DuoStim [17, 18, 20], whereas the remaining two reported no statistically significant difference between the two protocols regarding MII oocyte retrieval rate [19, 22]. Extracted data regarding number of MII oocytes obtained are presented in Table 8. Two studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing the mean number of MII oocytes retrieved between DuoStim and ConStim. The study in which results were reported as a median and range was excluded from the statistical analysis. Total heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 21%, P value0.26); thus, the fixed effect model was employed. Pooled data analysis revealed a statistically significant higher mean number of MII oocytes retrieved following DuoStim in comparison to ConStim (MD = 3.09, 95%CI = − 2.49, 3.7) (Fig. 15a). Two studies included in the statistical analysis comparing the MII oocyte rate between DuoStim and ConStim. Total heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 90%, P value = 0.001); thus, the random effects model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (OR = 0.96, 95%CI = 0.28, 3.27) between DuoStim and ConStim regarding the MII oocyte rate (Fig. 15b). Due to the high heterogeneity, observed results should not be considered as trustworthy. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 15.

Fig. 15.

Forest plot regarding the number of MII oocytes obtained resulting from the comparison of DuoStim and ConStim respectively. a Comparison of mean difference of MII oocytes. b Comparison of MII oocyte rate

Embryology data

Different criteria were used among the studies to evaluate the embryology data obtained following DuoStim and ConStim, respectively. In the study of Cardoso et al., no statistically significant difference was established between the two stimulation methods regarding the number of biopsied embryos, the number of euploid embryos, and the euploidy rate [18]. In the study of Liu et al., a statistically significant increased number of fertilized oocytes, number of cleaved embryos, number of cryopreserved embryos, and number of top-quality embryos was observed in the DuoStim group [20]. In the study of Martazanova et al., a statistically significant higher number of blastocyst was obtained following DuoStim in comparison to ConStim [17]. A statistically significant higher number of available embryos was reported in the study of Jin et al. in the DuoStim group, probably due to the higher number of oocytes retrieved in the same group [19]. Embryology data were not provided separately for DuoStim group and ConStim group in the study of Zhang et al. and Ubaldi et al. [9, 22].

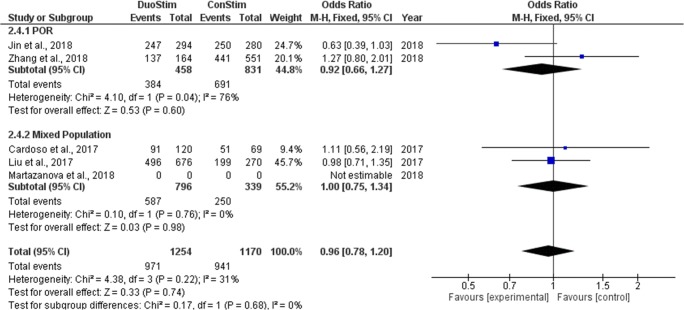

Fertilization rate

Four studies reported results regarding the fertilization rate observed following DuoStim and ConStim, respectively. All studies performed a retrospective data analysis [18–20, 22]. Fertilization rate ranged from 73.4 to 84.0% following DuoStim and from 73.6 to 89.3% following ConStim. No statistically significant difference was observed between DuoStim and ConStim in neither of the studies regarding fertilization rate. Extracted data regarding fertilization rate observed among the studies are presented in Table 9. Four studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing fertilization rate between DuoStim and ConStim. Total heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 31%, P value = 0.22); thus, the fixed effect model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (OR = 0.96, 95%CI = 0.78, 1.20) between DuoStim and ConStim regarding fertilization rate. Following subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in any of the two subgroups. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 16.

Table 9.

Extracted data regarding fertilization rate and clinical pregnancy rate observed following DuoStim and ConStim respectively

| Studies | Fertilization ratea | Clinical pregnancy rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DuoStim | ConStim | DuoStim | ConStim | |

| Cardoso et al., 2017 [18] | 91/120 (75.8%) | 51/69 (73.6%) | NA | NA |

| Liu et al. 2017 [20] | 496/676 (73.4%) | 199/270 (73.7%) | NA | NA |

| Martazanova et al. 2018 [17] | NA | NA | 39/76 (51.3%) | 30/72 (41.7%) |

| Jin et al., 2018 [19] | 247/294 (84%) | 250/280 (89.3%) | 19/52 (36.5%) | 17/56 (30.3%) |

| Zhang et al. 2018 [22] | 137/164 (83.5%) | 441/551 (80.0%) | 7/43 (16.2%) | 31/94 (33.0%) |

DuoStim double ovarian stimulation, ConStim conventional ovarian stimulation, NA not applicable

aFertilization rate defined as the number of 2PN zygotes obtained per inseminated oocytes

Fig. 16.

Forest plot of fertilization rate resulting from the comparison of DuoStim and ConStim respectively

Clinical pregnancy rate

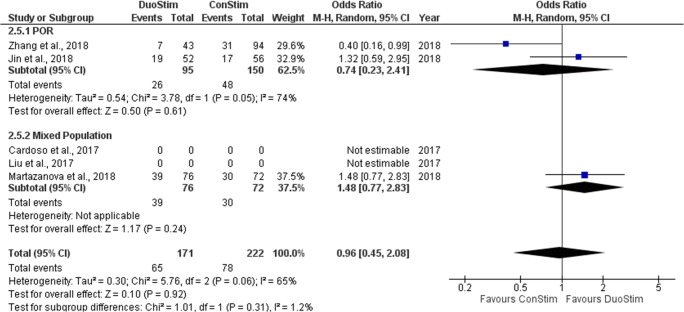

Three studies reported results regarding the CP observed following DuoStim and ConStim respectively. Two out of the three studies included performed a retrospective data analysis (Jin et al. and Zhang et al.) and one out of the three was of prospective nature [17]. In the study of Martazanova et al., a statistically higher CP rate observed in the DuoStim protocol [17]. In the studies of Jin et al. and Zhan et al., no statistical comparison between DuoStim and ConStim was attempted regarding the CP rate; thus, row data are presented [19, 22]. Extracted data regarding CP rate observed among the studies are presented in Table 9. Three studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing CP rate between DuoStim and ConStim. Total heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 65%, P value = 0.06); thus, the random effects model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (OR = 0.96, 95%CI = 0.45, 2.08) between DuoStim and ConStim regarding CP rate. Following subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in any of the two subgroups. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 17.

Fig. 17.

Forest plot of clinical pregnancy rate resulting from the comparison of DuoStim and ConStim respectively

Live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate

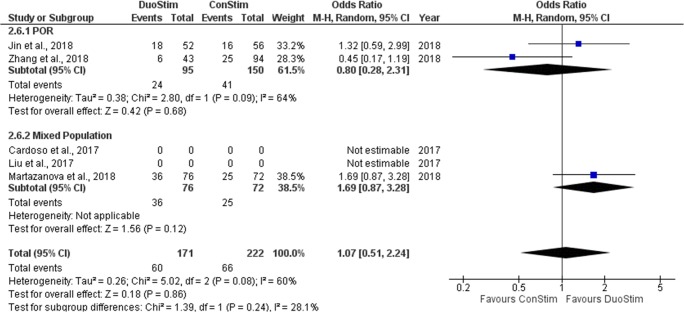

Three studies reported results regarding the LB/OP rate observed following DuoStim and ConStim respectively. Two out of the three studies included performed a retrospective data analysis [19, 22] and the other was of prospective nature [17]. In all of the studies, no statistical comparison between DuoStim and ConStim was attempted regarding the LB/OP rate, and thus, row data are presented. Extracted data regarding CP rate observed among the studies are presented in Table 10. Three studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing LB/OP rate between DuoStim and ConStim. Total heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 60%, P value = 0.08); thus, the random effects model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (OR = 1.07, 95%CI = 0.51, 2.24) between DuoStim and ConStim regarding LB/OP rate. Following subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in any of the two subgroups. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 18.

Table 10.

Extracted data regarding live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate and miscarriage/early pregnancy loss rate observed following DuoStim and ConStim, respectively

| Studies | Live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate | Miscarriage/early pregnancy loss rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DuoStim | ConStim | DuoStim | ConStim | |

| Cardoso et al. 2017 [18] | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Liu et al., 2017 [20] | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Martazanova et al. 2018 [17] | 36/76 (47.4%) | 25/72 (34.7%) | 3/39 (7.7%) | 5/30 (16.7%) |

| Jin et al. 2018 [19] | 18/52 (34.6%) | 16/56 (28.5%) | 1/19 (5.3%) | 1/17 (5.8%) |

| Zhang et al. 2018 [22] | 6/43 (14%) | 25/94 (26.6%) | 1/7 (14.3%) | 6/31 (19.4%) |

DuoStim double ovarian stimulation, ConStim conventional ovarian stimulation, NA not applicable

Fig. 18.

Forest plot of live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate resulting from the comparison of DuoStim and ConStim respectively

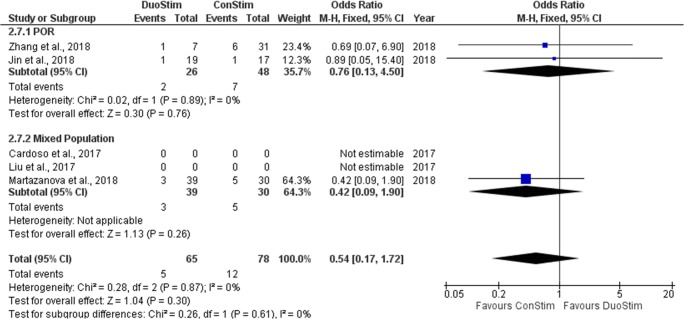

Miscarriage/early pregnancy loss rate

Three studies reported results regarding M/EPL rate observed following DuoStim and ConStim respectively. Two out of the three studies included performed a retrospective data analysis [19, 22] and the remaining was of prospective nature [17]. In the study of Martazanova et al., no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups [17]. In the studies of Jin et al. and Zhan et al., no statistical comparison between DuoStim and ConStim was attempted regarding the M/EPL rate, and thus, row data are presented [19, 22]. Extracted data regarding CP rate observed among the studies are presented in Table 10. Three studies were included in the statistical analysis comparing M/EPL rate between DuoStim and ConStim. Total heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 60%, P value = 0.08); thus, the fixed effect model was employed. Pooled data analysis failed to reveal any statistically significant difference (OR = 0.54, 95%CI = 0.17, 1.72) between DuoStim and ConStim regarding M/EPL rate. Following subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in any of the two subgroups. Statistical analysis is presented in Fig. 19.

Fig. 19.

Forest plot of miscarriage/early pregnancy loss rate resulting from the comparison of DuoStim and ConStim respectively

Discussion

Increasing interest on how to explore the phenomenon of multiple follicular waves during the same menstrual cycle has been noted in the field of ART. The majority of the available studies buttressing luteal phase ovarian stimulation retrieval have emerged recently. Hence, the outcome of employing such an approach and turning it into an established practice in the assisted reproduction field remains unclear, as guidelines or even an established consensus is lacking. In the present study, authors performed a systematic evaluation and meta-analysis on the efficacy of the DuoStim protocol in patients presenting with poor ovarian response. DuoStim presents as a novel strategy aiming to increase the number of retrieved oocytes, the number of good-quality embryos obtained, and subsequently the potential to achieve a live birth. This approach entails stimulation in the follicular phase, concluded by a subsequent stimulation in the luteal phase of the same menstrual cycle, and a double oocyte retrieval following each of the stimulation periods respectively. Following evaluation of the evidence published from inception of this approach to today, DuoStim appears to be correlated with a higher number of retrieved oocytes, higher number of mature MII oocytes, and higher number of available, good-quality embryos in comparison to ConStim. Some of the studies also reported a higher clinical pregnancy and live birth rate following DuoStim. In regard to the fertilization rate and the miscarriage rate/early pregnancy loss rate, sourced data demonstrated that the two protocols do not differ significantly. Further to that, data obtained from two studies indicated that cycle cancelation rate was considerably lower in patients subjected to DuoStim protocol in comparison to ConStim. However, understandably, patients who were subjected to a stimulation protocol twice during their menstrual cycle experienced a longer period of stimulation and a higher dose of exogenous gonadotropins in comparison to those undergoing ConStim. Since DuoStim includes two stimulation phases within the same menstrual cycle, the comparison of the efficacy of FPS and LPS may reveal further valuable information on the identity of luteal phase retrieved oocytes. The vast majority of the studies provided data demonstrating an equal performance and in vitro developmental competence of FPS and LP’S oocytes in regard to the fertilization rate, clinical pregnancy rate, live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate, and the miscarriage/early pregnancy loss rate. LPS seems to be correlated with an equal or an even higher performance in comparison to FPS regarding the total number of yielded oocytes, the number of mature oocytes, the number of available embryos, and the quality of obtained embryos. Studies providing data regarding the euploidy status of the embryos obtained from both phases conclude that LPS is not correlated with higher levels of aneuploidy in comparison to FPS. Considering the cycle cancelation rate, data shows that FPS and LPS do not statistically significantly differ. Nonetheless, there are studies demonstrating that FPS is more likely to result to failure of yielding any oocytes in comparison to LPS.

At this point, it should be highlighted that the studies included in this systematic review providing a meta-analytical approach have enrolled populations of varying characteristics and diverse infertility etiologies. Thus, the level of heterogeneity among them is considerably high. Further to that, the included studies herein employed different stimulation protocols and thus no safe conclusions could be extrapolated regarding the appropriate stimulation protocol when opting for the DuoStim strategy. This remains an area of heightened interest and respective investigation should follow. The main limitations of the present study are the restricted number of studies eligible for inclusion as well as the limited cohort of patients included in the majority of them. Numerous studies reporting on the initiation of stimulation randomly within the luteal phase followed by an oocyte retrieval at an unidentified time frame were encountered during literature search. These studies were excluded on the grounds that they would introduce confounders related to the true origin of the oocytes included in each study. Thus, authors focused strictly on studies reporting on double stimulation in the same patients in the same menstrual cycle ascertaining that the true origin of the oocytes retrieved could be identified. Prior to designing future randomized control trials (RCTs) to evaluate the DuoStim efficacy, certain inclusion and exclusion criteria should be methodically set and established. Most importantly the term of “poor ovarian response” should be carefully used and agreed upon. Recruitment of patients on the grounds of being of poor ovarian response should be strictly based on criteria that have achieved the status of a consensus, namely the Bologna criteria and/or POSEIDON stratification. The stimulation protocols employed should be fully disclosed enabling transparency and the potential for the results to be duplicated by researchers. A comparison between patients undergoing double FPS vs DuoStim should be performed as aptly suggested by Vaiarelli et al. [10].

Further studies are required to decipher the grounds on which the DuoStim approach should be employed in clinical practice. Accumulating the maximum number of oocytes in challenging cases such as of advanced maternal age or of poor ovarian response is imperative. Undoubtedly, double stimulation may in fact double the opportunity to retrieve adequate quality and quantity of oocytes [19]. However, one should not fail to take into account that double stimulation cycles submit patients to potentially excess of gonadotropins administration within a particularly narrow time frame, and respective studies should report on the short and long-term effects related to this. Concerns in regard to the overall patients’ health along with the possibility of complications entailed should be addressed prior to applying this approach generically and horizontally. In order to concur on the role of DuoStim and on how to best take advantage of the phenomenon of the second follicular wave within ART, examining whether the benefits outweigh the risks in cases of double stimulation cycles should be a priority. It is of interest that none of the studies included herein report on any complications associated to the practice or even provide confirmation that no complications were documented. The short time interval between performing the two stimulation protocols in DuoStim strategy merits a safety investigation that should not be overlooked. Examining parameters employing biomarkers may provide insight towards comprehending the differences regarding the physiology between the two ovarian follicular waves.

In light of the understandable hesitation regarding novel strategies application, this systematic review aims to raise awareness and familiarize practitioners with a phenomenon not yet widely known or embraced in clinical practice. The current status on DuoStim is viewed as a potential tool that may prospectively assist towards achieving an improved outcome in IVF cycles. Nonetheless, establishing optimal practice through definition of operating protocols employing the double follicular wave, along with what may be the short and long-term effects of DuoStim, remains a topic of interest. Standing evidence are in line with suggesting that the DuoStim protocol connecting FPS to LPS could be a promising option in managing patients presenting with poor ovarian response. Our conclusions on the true place of luteal phase oocyte retrieval—when performed within the DuoStim protocol—are strictly confined in the context of these patients. It is evident that the luteal phase oocyte retrieval favors an enhanced clinical outcome. It may still not be clear whether DuoStim stands as a generic or a rescue approach aiming to accumulate more oocytes and subsequent embryos targeting patients of poor ovarian response. Nonetheless, its employment may revolutionize their management. Interestingly, oocytes deriving from FPS and LPS present with similar potential and competence. This should be viewed with caution as the physiology regarding follicular recruitment and growth requires investigation. It should be highlighted that the subject of investigation in the present systematic review including a meta-analytical approach is to investigate the efficacy of performing a luteal phase stimulation rather than focusing on the safety or the long-term outcomes of such a practice—besides such data is not presently available. Larger RCTs with well-defined, strict criteria along with basic research should be conducted in order to delve into the molecular mechanisms and the physiology of the second follicular wave. Studies focused on designing the optimal approach in employing DuoStim in the context of assisted reproduction will contribute towards establishing a consensus. DuoStim entails a longer cumulative period of stimulation and a subsequent exposure to higher dosages of gonadotropin administration. Taking this into account, studies that report on cost-effectiveness are required and anticipated.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very appreciative to all clinicians, embryologists, and scientists at the Centre for Human Reproduction at Genesis Hospital and at the Department of Physiology of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Medical School.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Konstantinos Sfakianoudis and Konstantinos Pantos shared joint first authorship.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Block E. Quantitative morphological investigations of the follicular system in women. Eur J Endocrinol. 1951;8:33–54. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0080033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baerwald AR, Adams GP, Pierson RA. Characterization of ovarian follicular wave dynamics in women. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1023–1031. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baerwald AR, Adams GP, Pierson RA. A new model for ovarian follicular development during the human menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:116–122. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00544-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groome N P, Illingworth P J, O'Brien M, Pai R, Rodger F E, Mather J P, McNeilly A S. Measurement of dimeric inhibin B throughout the human menstrual cycle. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1996;81(4):1401–1405. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.4.8636341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baerwald AR, Adams GP, Pierson RA. Ovarian antral folliculogenesis during the human menstrual cycle: a review. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;18:73–91. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuang Yanping, Chen Qiuju, Hong Qingqing, Lyu Qifeng, Ai Ai, Fu Yonglun, Shoham Zeev. Double stimulations during the follicular and luteal phases of poor responders in IVF/ICSI programmes (Shanghai protocol) Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2014;29(6):684–691. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rashtian Justin, Zhang John. Luteal-phase ovarian stimulation increases the number of mature oocytes in older women with severe diminished ovarian reserve. Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine. 2018;64(3):216–219. doi: 10.1080/19396368.2018.1448902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sfakianoudis Konstantinos, Simopoulou Mara, Maziotis Evangelos, Giannelou Polina, Tsioulou Petroula, Rapani Anna, Pantou Agni, Petroutsou Konstantina, Angeli Irene, Deligeoroglou Efthymios, Koutsilieris Michael, Pantos Konstantinos. Evaluation of the Second Follicular Wave Phenomenon in Natural Cycle Assisted Reproduction: A Key Option for Poor Responders through Luteal Phase Oocyte Retrieval. Medicina. 2019;55(3):68. doi: 10.3390/medicina55030068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ubaldi Filippo Maria, Capalbo Antonio, Vaiarelli Alberto, Cimadomo Danilo, Colamaria Silvia, Alviggi Carlo, Trabucco Elisabetta, Venturella Roberta, Vajta Gábor, Rienzi Laura. Follicular versus luteal phase ovarian stimulation during the same menstrual cycle (DuoStim) in a reduced ovarian reserve population results in a similar euploid blastocyst formation rate: new insight in ovarian reserve exploitation. Fertility and Sterility. 2016;105(6):1488-1495.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaiarelli A, Cimadomo D, Trabucco E, Vallefuoco R, Buffo L, Dusi L, et al. Double stimulation in the same ovarian cycle (DuoStim) to maximize the number of oocytes retrieved from poor prognosis patients: a multicenter experience and SWOT analysis. Frontiers in Endocrinology. Frontiers; 2018;9:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Creux H, Monnier P, Son W-Y, Tulandi T, Buckett W. Immature oocyte retrieval and in vitro oocyte maturation at different phases of the menstrual cycle in women with cancer who require urgent gonadotoxic treatment. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maman Ettie, Meirow Dror, Brengauz Masha, Raanani Hila, Dor Jehushua, Hourvitz Ariel. Luteal phase oocyte retrieval and in vitro maturation is an optional procedure for urgent fertility preservation. Fertility and Sterility. 2011;95(1):64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Ningling, Wang Yun, Chen Qiuju, Dong Jing, Tian Hui, Fu Yonglun, Ai Ai, Lyu Qifeng, Kuang Yanping. Luteal-phase ovarian stimulationvsconventional ovarian stimulation in patients with normal ovarian reserve treated for IVF: a large retrospective cohort study. Clinical Endocrinology. 2015;84(5):720–728. doi: 10.1111/cen.12983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mcnatty Kenneth P., Hillier Stephen G., van den Boogaard Agnes M. J., Trimbos-Kemper Trudy C. M., Reichert Leo E., van Hall Eylard V. Follicular Development during the Luteal Phase of the Human Menstrual Cycle. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1983;56(5):1022–1031. doi: 10.1210/jcem-56-5-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moffat Rebecca, Pirtea Paul, Gayet Vanessa, Wolf Jean Philippe, Chapron Charles, de Ziegler Dominique. Dual ovarian stimulation is a new viable option for enhancing the oocyte yield when the time for assisted reproductive technnology is limited. Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2014;29(6):659–661. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madani T, Hemat M, Arabipoor A, Khodabakhshi SH, Zolfaghari Z. Double mild stimulation and egg collection in the same cycle for management of poor ovarian responders. Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics and Human Reproduction. 2019;48(5):329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martazanova B, Mishieva N, Bogatyreva K, Veyukova M, Kodileva T, Burmenskaya O, et al. Double stimulation in a single menstrual cycle in patients with reduced ovarian reserve: hormonal characteristics, cumulus cell gene expression, embryological and clinical outcome. Human Reproduction. Oxford Univ Press Great Clarendon St, Oxford OX2 6DP, England; 2018. p. 80.

- 18.de Almeida Cardoso MC, Evangelista A, Sartório C, Vaz G, Werneck CLV, Guimarães FM, et al. Can ovarian double-stimulation in the same menstrual cycle improve IVF outcomes? JBRA Assisted Reproduction. 2017;21:217. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20170042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin B, Niu Z, Xu B, Chen Q, Zhang A. Comparison of clinical outcomes among dual ovarian stimulation, mild stimulation and luteal phase stimulation protocols in women with poor ovarian response. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2018;34:694–697. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1435636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Conghui, Jiang Hong, Zhang Wenxiang, Yin Huiqun. Double ovarian stimulation during the follicular and luteal phase in women ≥38 years: a retrospective case-control study. Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2017;35(6):678–684. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Q, Guo XM, Li Y. Implantation rates subsequent to the transfer of embryos produced at different phases during double stimulation of poor ovarian responders. Reproduction, Fertility and Development. CSIRO; 2017;29:1178–1183. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Zhang W, Wang M, Wang S, Bao H, Qu Q, Zhang N, et al. Luteal phase ovarian stimulation for poor ovarian responders. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2018;22:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Pacchiarotti Alessandro, Selman Helmy, Valeri Claudia, Napoletano Simona, Sbracia Marco, Antonini Gabriele, Biagiotti Giulio, Pacchiarotti Arianna. Ovarian Stimulation Protocol in IVF: An Up-to-Date Review of the Literature. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2016;17(4):303–315. doi: 10.2174/1389201017666160118103147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatirnaz S, Ata B, Hatırnaz E, Basbug A, Tannus S. Dual oocyte retrieval and embryo transfer in the same cycle for women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2019;145:23–27. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campos APCB, Geber GP, Hurtado R, Sampaio M, Geber S. Ovarian response after random-start controlled ovarian stimulation to cryopreserve oocytes in cancer patients. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2018;22:381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Tsampras N, Gould D, Fitzgerald CT. Double ovarian stimulation (DuoStim) protocol for fertility preservation in female oncology patients. Hum Fertil. Taylor & Francis. 2017;20:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Leahomschi S. Duostim protokol v managementu a léčbě pacientek s nízkou odpovědí na kontrolovanou ovariální hyperstimulaci. 2018;

- 28.Cimadomo D, Vaiarelli A, Colamaria S, Trabucco E, Alviggi C, Venturella R, et al. Luteal phase anovulatory follicles result in the production of competent oocytes: intra-patient paired case-control study comparing follicular versus luteal phase stimulations in the same ovarian cycle. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1442–1448. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Oct 13];355. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5062054/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]