Abstract

Apoptosis, a type of programmed cell death that plays a key role in both healthy and pathological conditions, releases extracellular vesicles such as apoptotic bodies and microvesicles, but exosome release due to apoptosis is not yet commonly accepted. Here, the reports demonstrating the presence of apoptotic exosomes and their roles in inflammation and immune responses are summarized, together with a general summary of apoptosis and extracellular vesicles. In conclusion, apoptosis is not just a ‘silent’ type of cell death but an active form of communication from dying cells to live cells through exosomes.

Subject terms: Apoptosis, Cell death and immune response

Intercellular communication: dying cells send out messages

Dying cells communicate with healthy cells through molecular messages contained in tiny membrane-encapsulated vesicles called exosomes. In a review article, Yong-Joon Chwae from Ajou University School of Medicine in Suwon, South Korea, and colleagues discuss how these ‘apoptotic exosomes’ play important roles in immune regulation, with implications for various diseases including inflammatory disorders, cancer, neurodegeneration and infection. Researchers have long known that cells undergoing programmed cell death release vesicles that contain cellular debris, but these larger apoptotic bodies were considered mostly a messy byproduct of the dying process. Recent reports have highlighted the existence of much smaller apoptotic exosomes, each containing signals that aid in triggering and modulating immune responses. Manipulation of these exosomes or their signaling pathways could lead to new treatments for diseases linked to faulty intercellular communication and waste disposal.

Apoptotic cell death

Apoptosis, the most commonly occurring programmed cell death process, is a highly organized and energy-dependent process involving caspases in multicellular organisms1,2. The apoptotic process was first described by the German scientist Carl Vogt in 1842, and the term “apoptosis” was first coined by the John Foxton Ross Kerr group in 19721. Apoptosis removes many cells every single day, with adult human losses of approximately 50 billion cells on average per day3. In contrast to primary necrosis (traumatic cell death resulting from acute cell damage), apoptosis is a highly regulated and controlled process that aids in the removal of unwanted cells during the whole life cycle of every organism. During apoptosis, cell shrinkage and chromatin condensation occur. Due to shrinkage, the cells appear small in size with tightly packed organelles and cytoplasm. Finally, extensive plasma membrane blebbing and nuclear fragmentation lead to the formation of apoptotic bodies, which are engulfed and removed sequentially by phagocytic cells to prevent spillover and damage to the surrounding cells or tissues4–9.

Apoptosis can be classified into intrinsic and extrinsic pathways based on the mode of initial activation. In the intrinsic pathway (mitochondrial pathway), activation of apoptosis begins with internal signals generated from stressed cells and depends on cytoplasmic release of a protein in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, cytochrome C, through the mitochondrial outer membrane pores. BCL-2 family proteins are reported to be major regulators and effectors of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, resulting in the release of cytochrome C from the mitochondrial intermembrane space10. BCL-2 family proteins include effector proteins (BAX and BAK), the proapoptotic BH3-only proteins (Bad, Bid, Bik, Bim, Bmf, Hrk, Noxa, and Puma) and antiapoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bcl-w, Mcl-1, and A1)10,11. BH3-only members play a key role in activating BAX and BAK directly or indirectly. Upon their activation, BAX and BAK form homo-oligomers on the outer membrane of mitochondria with formation of membrane pores, leading to cytochrome C release into the cytosol11. Cytosolic cytochrome C then binds to Apaf-1 and forms apoptosomes together with procaspase-9, which triggers autocleavage of procaspase-9 to active caspase-9. Activated caspase-9 further activates the caspase cascade, leading to apoptosis4. The activation of receptors is required for the extrinsic pathway through members of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily, including FAS (CD95) and TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptors. Activation of the extrinsic pathway is mediated through the binding of death ligands (TNFα, FAS, and TRAIL) to their receptors, subsequently leading to trimerization and clustering of the cytosolic death domains (DDs) of receptors, to which adapter molecules such as Fas-associated death domain (FADD) or TNFR-associated death domain (TRADD) are bound. Then, adapters recruit initiator caspases, including procaspase-8 and procaspase-10, through their death effector domains (DEDs), resulting in the formation of a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC)4. Then, initiator caspases activated by autocleavage in the DISC activate downstream executioner caspases, including caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-712,13.

Caspases are a group of proteases mainly known for their crucial role in programmed cell death, including apoptosis and pyroptosis, and the inflammatory pathway. The name caspase is an abbreviation of cysteine protease activity. Caspases have been classified into apoptotic caspases, including caspase-3, caspase-6, caspase-7, caspase-8, and caspase-9 in mammals, and inflammatory caspases, including caspase-1, caspase-4, caspase-5, and caspase-12 in humans and caspase-1, caspase-11, and caspase-12 in mice14. In addition, based on the mechanism of action, apoptotic caspases are further classified into either initiator caspases, which include caspase-8 and caspase9, or executioner caspases, which include caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-7. Caspases are initially produced in an inactive form called procaspases, which require dimerization or cleavage to become active caspases14,15.

Extracellular vesicles

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are small membrane-bound vesicles that are produced from both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells in normal physiological, as well as pathological conditions. These vesicles contain various contents, such as protein, DNA, miRNA and mRNA16. Based on their morphologies, modes of biogenesis, or contents, EVs are classified into three main categories: apoptotic bodies (ApoBDs), microvesicles (MVs) and exosomes17,18. Apoptotic bodies (ApoBDs) range from 50 to 5000 nm in diameter, close to the size of platelets, and are produced from cells undergoing programmed cell death17,19. During apoptosis of a cell, ApoBDs are formed during plasma membrane blebbing9. Later, these apoptotic bodies are phagocytosed by macrophages and fuse with lysosomes (phagolysosomes) within macrophages to prevent spillover and damage to the surrounding cell or tissue. ApoBDs can be detected using flow cytometry20. Microvesicles (MVs) are also known as ectosomes or microparticles21 and range in size from 100 to 1000 nm22. MVs arise by outward budding and fission of the plasma membrane. This mechanism is mediated through the interaction of phospholipid redistribution and cytoskeletal protein contraction16. MVs are often involved in intercellular communication, signal transduction, and immune regulation. MVs, in particular, participate in tumor invasion, metastases, coagulation, inflammation, stem-cell renewal and expansion22. MVs are also reported to have Annexin V, Flotillin-2, selectin, integrin, CD40, and metalloproteinase as markers23 and are widely detected in various biological fluids (peripheral blood, urine and ascitic fluids)24. Exosomes are a type of EV originating from endosomes with a size of 30–150 nm and a specific density of 1.13–1.21 g/mL. These EVs are reported to play crucial roles in intercellular communications and waste disposal in normal and pathologic conditions such as cancers, neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and infectious diseases25,26. In particular, exosomes derived from tumors are loaded with tumor antigens that can activate dendritic cells and are involved in triggering immune responses to recognize tumors and induce cytotoxic responses against tumors. Therefore, injection of tumor exosomes can suppress tumor growth or reject tumors by inducing an immune response and subsequent activation of macrophages and natural killer cells27. Exosomes are produced from late endosomes called multivesicular bodies (MVBs). Invagination of the late endosomal membrane results in the generation of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs)26. The invagination of the endosomal membrane results in the enclosure of some proteins and cytosolic components (lipids, nucleic material including DNA, mRNA, microRNA, small-interfering RNA) within the newly formed ILVs. Finally, the fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane releases the ILVs into the extracellular space; these molecules are then referred to as exosomes28,29. Exosomes can be found in most biological fluids, including urine, breast milk, plasma, saliva, cerebral spinal fluid, amniotic fluid, ascites, bile, and semen17,30. Exosomes have been reported to have HSP 70, CD63, CD81, CD9, LAMP1, and TSG101 as markers23,31.

Apoptotic extracellular vesicles

As described above, EVs are generally classified depending on their biogenetic mechanisms as exosomes, microvesicles (MVs) and apoptotic bodies32,33. Exosomes and MVs have been widely studied and have important roles in several intercellular communication mechanisms, including antigen-specific immune responses mediated by exosomes with enrichment of MHC class II molecules34–36, and modulate anti-inflammatory effects via secretion of TGF-β137. Findings reported by Valadi et al. showing that exosomes can carry nucleic acids and mRNA from mouse-derived exosomes into human cells have shed light on how EVs can contribute to intercellular communication and their potent roles in clinical application38. Similarly, the presence of mRNA from tumor cell-derived MVs has been reported39, in addition to the identification of miRNAs from the MVs isolated from blood40.

Similar to healthy cells, apoptotic cells can also release extracellular vesicles (termed apoptotic extracellular vesicles, ApoEVs). Among them, apoptotic bodies, which were first demonstrated by Kerr et al., were originally considered cell debris and disregarded in mainstream EV research. These molecules are generally described as vesicles with a size of up to 5 µm in diameter that carry nuclear fragments and cellular organelles such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum as a result of apoptosis. Therefore, EVs for immune regulation often require the removal of apoptotic bodies because many clinical sample-derived EVs are likely to be heterogeneous16,41,42. Some research, however, further examined apoptotic bodies with a size of less than 1 µm and defined them as apoptotic microvesicles (ApoMVs), which are physiologically different from traditional apoptotic bodies, as they have a superior membrane integrity for molecular exchange5,43–45.

Apoptosis has been considered a form of ‘silent’ cell death for a long time, in contrast to necrosis, which frequently induces inflammation by releasing danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). However, this notion has changed, and apoptosis has gradually been shown to participate in communication with neighboring cells to contribute to survival or apoptosis and remodeling of the surrounding tissues46. Some studies argue that apoptotic cell death can elicit inflammatory and immune responses under certain circumstances47–50, and recent studies have suggested that apoptotic vesicles derived from dying cells may be one of the main regulators of the corresponding immune regulation41,42,51,52. ApoEVs have been suggested to have similar characteristics to those EVs formed from healthy cells in terms of cargo delivery, including apoptotic byproducts from apoptotic clearance42,53, and immune regulation such as inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer in relation to what molecular cargoes are carried51,52,54.

In this regard, it is worth noting that dying cells, including apoptotic cells, definitely release more EVs than healthy cells55,56. Moreover, a recent study showed that apoptotic cells can release MVs and exosomes in addition to ApoBDs57. Apoptotic MVs (0.2–1 µm in diameter), also called apoptotic microparticles, are presumed to be synthesized by plasma membrane budding in apoptotic processes and are known to induce proinflammatory cytokines through the transfer of their cargo to recipient dendritic cells or to suppress the immune system43,58–60.

Apoptotic exosomes (ApoExos)

Apoptotic cell-derived exosomes or apoptotic exosomes (ApoExos) are the latest discovered entity of ApoEVs, and therefore, this name is yet generally accepted. Defining exosomes in apoptosis is difficult for several reasons. First, ApoEVs released during apoptosis are a highly heterogeneous population compared to those released from healthy cells, and thus, it is technically difficult to isolate the pure exosomal fraction61. Second, various EVs have common marker proteins, and thus far, unique markers for ApoExos have not been well studied33,44. Third, it is fairly difficult to determine that the exosomal fraction from apoptosis originates from endosomes because dying cells rapidly go through phenotypic changes from cellular shrinkage and plasma membrane blebs to either disintegrated cell bodies, called apoptotic bodies, or pyroptic changes called secondary necrosis62,63.

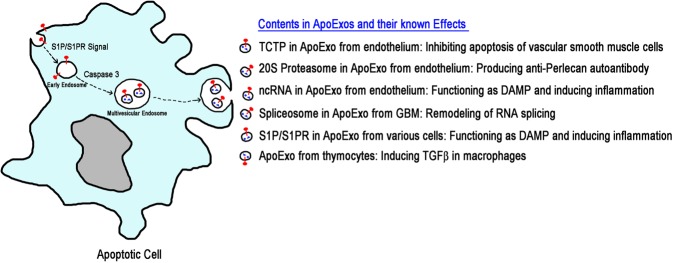

Nevertheless, the presence of ApoExos was elucidated in the serially published seminal articles of Hebert’s group. These researchers reported the caspase 3-dependent formation of MVBs and the release of ApoExos in endothelial cells, resulting in the delivery of Translationally Controlled Tumor Protein (TCTP); inhibited apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells; and the active 20S proteasome core in circulating ApoExos, which induced production of anti-perlecan autoantibodies and allogeneic graft rejection. These results confirmed that ApoExos contribute to intercellular communication and immune responses, similar to exosomes from healthy cells64–66. In addition, in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), an aggressive brain cancer, it was recently reported that components of the spliceosomes contained in ApoExos promote tumor cell proliferation and confer therapeutic resistance to live tumor cells via remodeling of the RNA splicing patterns67. Interestingly, ApoExos produced from endothelial cells deliver noncoding RNAs, characterized by sequences rich in uridine and reminiscent of viral RNAs, which can stimulate RIG-I-like receptors and TLRs to induce inflammation68, while ApoExos from thymocytes suppresses immune responses by induction of TGFβ in macrophages69.

Recent research has further identified ApoExos, which share common features of exosomes with regard to their physical characteristics, such as size, density and protein expression, in addition to their roles in intercellular communication52. Proteins such as CD63, CD9, CD81, and HSP70 are widely recognized as marker proteins of21,32 exosomes, and it is generally agreed that the biogenesis of exosomes is highly associated with the endosomal-lysosomal pathway accompanied by the ESCRT complex70. ApoExos, as shown by Park et al., express the typical exosomal marker CD63 in addition to the lysosomal marker LAMP1 and the stress-associated protein HSP70, which is expressed under apoptotic conditions. These apoptotic vesicles have been termed apoptotic exosome-like vesicles (AEVs) with unique protein markers (i.e., Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptors 1 and 3, S1PR1/3) and have been proposed to be induced by damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). These changes induce proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, from macrophages through S1P/S1PR signals in ApoExos and consequent activation of NF-κB and p38 MAPK in macrophages. Biogenesis of ApoExos has been reported to be associated with S1P signaling initiated by S1PR1/3 from the plasma membrane at the early apoptotic phase, progressing to endosomal maturation, mainly by the downstream Gβγ subunit of S1PR1/3 and subsequent actin mobilization52.

Despite the limited information on ApoExos, the data described above clearly show that ApoExos could be associated with various human pathophysiological conditions as either DAMPs or carriers for functional molecules to modulate recipient cells, which are produced by a unique MVB maturation pathway with wholly different cargos from conventional exosomes52,71. Thus, exosomes from dying cells are neither simple remnants nor disintegrated cell bodies that needed to be scavenged but are instead final messages from dying cells to the remaining live cells.

Concluding remarks

ApoExos exist and play a crucial role in various pathological and physiological conditions of humans despite the limited known information, as summarized together with the biogenetic mechanisms in Fig. 1. Thus, future studies have revealed the roles of ApoExos in various disease settings. These works should focus on human diseases whose etiologies are implicated in chronic inflammation or immune responses, such as cancers, chronic allergies, autoimmune diseases, and neuroskeletal and musculoskeletal degenerative diseases, given that most reports elucidated the roles of ApoExos in the induction of inflammation or specific immune responses as described above. In another aspect, ApoEVs are extremely heterogeneous with relatively high levels; thus, purification and definition of ApoExos, intermingled with other types of ApoEVs, must be carefully approached9.

Fig. 1. Illustration depicting current findings on ApoExos.

Biogenesis of ApoExos begins with S1P/S1PR signals on the plasma membrane and requires caspase 3 for maturation of MVBs. ApoExos are associated with various pathophysiologic events, such as vascular homeostasis, autoimmunity and the resultant graft rejection, sterile inflammation, and proliferation and survival of tumors.

The level of ApoExo release is completely different in the various types of cells52, suggesting that only the cells or tissues equipped with the systems necessary for ApoExo biogenesis could release ApoExos; otherwise, specific cellular stresses leading to apoptotic cell death might be needed for ApoExo release. However, unfortunately, the biogenetic mechanisms of ApoExos are poorly understood and have only begun to be elucidated. Hence, efforts to investigate the biogenetic mechanisms and functional studies should be undertaken. These studies would provide helpful clues for the development of new therapeutics based on modulation of ApoExo release in human diseases and promote future use of these molecules as vehicles of drug delivery and gene therapy similar to exosomes72–75.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by Ministry of Education Grants, NRF-2018R1D1A1B07048257, NRF-2017R1D1A1B03034312, and NRF-2016R1D1A1B03934488, by Grant HI16C0992 from the Korea Health Technology Research and Development Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of the Republic of Korea, and by a grant (RB201907-1-R1) from the Jeonbuk Research and Development Program funded by Jeonbuk Province.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ramesh Kakarla, Jaehark Hur

References

- 1.Hongmei, Z. Extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis signal pathway review. Apoptosis Med. 1, 3–22 (2012).

- 2.Green, DR. Means to an End: Apoptosis and Other Cell Death Mechanisms (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2011).

- 3.Raj D, Brash DE, Grossman D. Keratinocyte apoptosis in epidermal development and disease. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2006;126:243–257. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wickman GR, et al. Blebs produced by actin–myosin contraction during apoptosis release damage-associated molecular pattern proteins before secondary necrosis occurs. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:1293–1305. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wickman G, Julian L, Olson M. How apoptotic cells aid in the removal of their own cold dead bodies. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:735. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Häcker G. The morphology of apoptosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:5–17. doi: 10.1007/s004410000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oberhammer FA, Hochegger K, Froschl G, Tiefenbacher R, Pavelka M. Chromatin condensation during apoptosis is accompanied by degradation of lamin A+B, without enhanced activation of cdc2 kinase. J. Cell Biol. 1994;126:827–837. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.4.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thery C, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2018;7:1535750. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shamas-Din A, Kale J, Leber B, Andrews DW. Mechanisms of action of Bcl-2 family proteins. Cold. Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a008714. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, Huang K, O'Neill KL, Pang X, Luo X. Bax/Bak activation in the absence of Bid, Bim, Puma, and p53. Cell Death. Dis. 2016;7:e2266. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel V, Balakrishnan K, Keating MJ, Wierda WG, Gandhi V. Expression of executioner procaspases and their activation by a procaspase-activating compound in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 2015;125:1126–1136. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-546796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parrish AB, Freel CD, Kornbluth S. Cellular mechanisms controlling caspase activation and function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a008672. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McIlwain DR, Berger T, Mak TW. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a008656–a008656. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riedl SJ, Shi Y. Molecular mechanisms of caspase regulation during apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:897–907. doi: 10.1038/nrm1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akers JC, Gonda D, Kim R, Carter BS, Chen CC. Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles (EV): exosomes, microvesicles, retrovirus-like vesicles, and apoptotic bodies. J. Neurooncol. 2013;113:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1084-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barros, F. M., Carneiro, F., Machado, J. C. & Melo, SA. Exosomes and immune response in cancer: friends or foes? Front. Immunol.9, 730 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Mashouri L, et al. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis, and mechanisms in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:75. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0991-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Console L, Scalise M, Indiveri C. Exosomes in inflammation and role as biomarkers. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2019;488:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wlodkowic D, Telford W, Skommer J, Darzynkiewicz Z. Apoptosis and beyond: cytometry in studies of programmed cell death. Methods Cell Biol. 2011;103:55–98. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385493-3.00004-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanez-Mo M, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Li G, Liu M-L. Microvesicles as emerging biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cardiometabolic diseases. Genomics Proteom. Bioinforma. 2018;16:50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borges FT, Reis LA, Schor N. Extracellular vesicles: structure, function, and potential clinical uses in renal diseases. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2013;46:824–830. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20132964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muralidharan-Chari V, Clancy JW, Sedgwick A, D'Souza-Schorey C. Microvesicles: mediators of extracellular communication during cancer progression. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:1603–1611. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran T-H, Mattheolabakis G, Aldawsari H, Amiji M. Exosomes as nanocarriers for immunotherapy of cancer and inflammatory diseases. Clin. Immunol. 2015;160:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minciacchi VR, Freeman MR, Di Vizio D. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: exosomes, microvesicles and the emerging role of large oncosomes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015;40:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Toro J, Herschlik L, Waldner C, Mongini C. Emerging roles of exosomes in normal and pathological conditions: new insights for diagnosis and therapeutic applications. Front. Immunol. 2015;6:203. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Liu Y, Liu H, Tang WH. Exosomes: biogenesis, biologic function and clinical potential. Cell Biosci. 2019;9:19. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahu R, et al. Microautophagy of cytosolic proteins by late endosomes. Dev. Cell. 2011;20:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gurunathan S, Kang M-H, Jeyaraj M, Qasim M, Kim J-H. Review of the isolation, characterization, biological function, and multifarious therapeutic approaches of exosomes. Cells. 2019;8:307. doi: 10.3390/cells8040307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.György B, et al. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol. Life. Sci. 2011;68:2667–2688. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014;30:255–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gould, S. J. & Raposo, G. As we wait: coping with an imperfect nomenclature for extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles.2, 20389 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Hessvik NP, Llorente A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell Mol. Life. Sci. 2018;75:193–208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2595-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bobrie A, Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Exosome secretion: molecular mechanisms and roles in immune responses. Traffic. 2011;12:1659–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaput N, Thery C. Exosomes: immune properties and potential clinical implementations. Semin. Immunopathol. 2011;33:419–440. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gasser O, Schifferli JA. Activated polymorphonuclear neutrophils disseminate anti-inflammatory microparticles by ectocytosis. Blood. 2004;104:2543–2548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valadi H, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baj-Krzyworzeka M, et al. Tumour-derived microvesicles carry several surface determinants and mRNA of tumour cells and transfer some of these determinants to monocytes. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2006;55:808–818. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunter MP, et al. Detection of microRNA expression in human peripheral blood microvesicles. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3694–e3694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atkin-Smith GK, et al. A novel mechanism of generating extracellular vesicles during apoptosis via a beads-on-a-string membrane structure. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7439. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poon IKH, Lucas CD, Rossi AG, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell clearance: basic biology and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:166. doi: 10.1038/nri3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schiller M, et al. Induction of type I IFN is a physiological immune reaction to apoptotic cell-derived membrane microparticles. J. Immunol. 2012;189:1747–1756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lotvall J, et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2014;3:26913. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winau F, et al. Apoptotic vesicles crossprime CD8 T cells and protect against tuberculosis. Immunity. 2006;24:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perez-Garijo A, Steller H. Spreading the word: non-autonomous effects of apoptosis during development, regeneration and disease. Development. 2015;142:3253–3262. doi: 10.1242/dev.127878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Faouzi S, et al. Anti-Fas induces hepatic chemokines and promotes inflammation by an NF-kappa B-independent, caspase-3-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:49077–49082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joshi VD, Kalvakolanu DV, Cross AS. Simultaneous activation of apoptosis and inflammation in pathogenesis of septic shock: a hypothesis. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuwano K, Hara N. Signal transduction pathways of apoptosis and inflammation induced by the tumor necrosis factor receptor family. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2000;22:147–149. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.2.f178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morillas Pedro, de Andrade Helder, Castillo Jesus, Quiles Juan, Bertomeu-González Vicente, Cordero Alberto, Tarazón Estefanía, Roselló Esther, Portolés Manuel, Rivera Miguel, Bertomeu-Martínez Vicente. Inflammation and Apoptosis in Hypertension. Relevance of the Extent of Target Organ Damage. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition) 2012;65(9):819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caruso S, Poon IKH. Apoptotic cell-derived extracellular vesicles: more than just debris. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1486–1486. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park SJ, et al. Molecular mechanisms of biogenesis of apoptotic exosome-like vesicles and their roles as damage-associated molecular patterns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E11721–E11730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811432115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hochreiter-Hufford A, Ravichandran KS. Clearing the dead: apoptotic cell sensing, recognition, engulfment, and digestion. Cold. Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a008748. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gregory CD, Dransfield I. Apoptotic tumor cell-derived extracellular vesicles as important regulators of the onco-regenerative niche. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1111. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Distler JH, et al. The release of microparticles by apoptotic cells and their effects on macrophages. Apoptosis. 2005;10:731–741. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-2941-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baxter AA, et al. Analysis of extracellular vesicles generated from monocytes under conditions of lytic cell death. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:7538. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44021-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tucher C, et al. Extracellular vesicle subtypes released from activated or apoptotic T-lymphocytes carry a specific and stimulus-dependent protein cargo. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:534. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thery C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dieker J, et al. Circulating apoptotic microparticles in systemic lupus erythematosus patients drive the activation of dendritic cell subsets and prime neutrophils for NETosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:462–472. doi: 10.1002/art.39417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ainola M, et al. Activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells by apoptotic particles-mechanism for the loss of immunological tolerance in Sjögren's syndrome. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2018;191:301–310. doi: 10.1111/cei.13077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kowal J, et al. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E968–977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tixeira R, Poon IKH. Disassembly of dying cells in diverse organisms. Cell Mol. Life. Sci. 2019;76:245–257. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2932-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Atkin-Smith GK, Poon IKH. Disassembly of the dying: mechanisms and functions. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sirois I, et al. Caspase-3-dependent export of TCTP: a novel pathway for antiapoptotic intercellular communication. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:549–562. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sirois I, et al. Caspase activation regulates the extracellular export of autophagic vacuoles. Autophagy. 2012;8:927–937. doi: 10.4161/auto.19768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dieude M, et al. The 20S proteasome core, active within apoptotic exosome-like vesicles, induces autoantibody production and accelerates rejection. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:318ra200. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac9816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pavlyukov MS, et al. Apoptotic cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote malignancy of glioblastoma via intercellular transfer of splicing factors. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:119–135 e110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hardy MP, et al. Apoptotic endothelial cells release small extracellular vesicles loaded with immunostimulatory viral-like RNAs. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:7203. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43591-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen H, et al. Extracellular vesicles from apoptotic cells promote TGFβ production in macrophages and suppress experimental colitis. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:5875. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42063-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eitan E, Suire C, Zhang S, Mattson MP. Impact of lysosome status on extracellular vesicle content and release. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016;32:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abramowicz A, et al. Ionizing radiation affects the composition of the proteome of extracellular vesicles released by head-and-neck cancer cells in vitro. J. Radiat. Res. 2019;60:289–297. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrz001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Trovato E, Di Felice V, Barone R. Extracellular vesicles: delivery vehicles of myokines. Front. Physiol. 2019;10:522. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lim W, Kim HS. Exosomes as therapeutic vehicles for cancer. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019;16:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s13770-019-00190-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sterzenbach U, et al. Engineered exosomes as vehicles for biologically active proteins. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1269–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang H, et al. Exosome-induced regulation in inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1464. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]