Abstract

The term ‘language testing and assessment’ (LTA) seems to often invoke ideas related to numbers, such as mathematical equation and statistical calculation. This may range from scoring performance or responses to examination questions as numbers, to informing stakeholders of test results. This article investigates a series of actions pertaining to LTA by bringing in reflexive ethnography (Davies, C.A. [2008]. Reflexive Ethnography: A Guide to Researching Selves and Others. Routledge: London.). The aims are to add a humanistic element to the discipline in general and to feed another piece of applicability information to ethnographers in particular. Attempting at introducing such an approach largely qualitative as ethnography to the field of LTA can be useful because it may open up possibilities for balanced views in assessing language competence in future studies, in which social factors can also be taken explicitly into account for a decision making in LTA. For ethnographers, applicability of reflexive ethnography in LTA could mean the methodology achieves greater generalizability through a larger sample in the universe of admissible observations. A primary research question is whether a change in using CEFR-oriented placement test scores can be justified using empirical reasoning. Participatory observations, situational weigh-in, and statistical analyses are found capable of synergizing using a reflexive-ethnographic perspective for a justifiable decision-making process.

Keywords: Program evaluation, Placement test, Language assessment, Reflexive ethnography, Justification, Linguistics, Applied linguistics, Education, Sociology, Ethnography

Program evaluation; Placement test; Language assessment; Reflexive ethnography; Justification; Linguistics; Applied Linguistics; Education; Sociology; Ethnography

1. Introduction

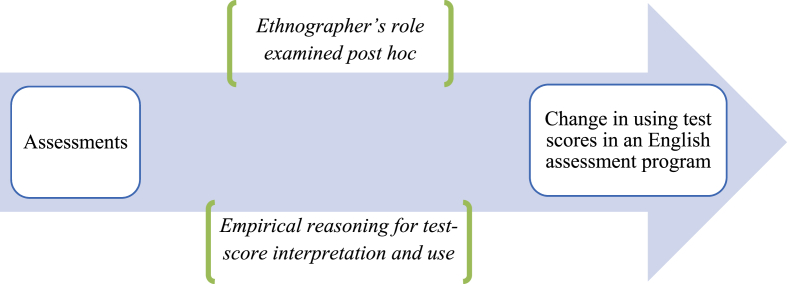

Reflexive ethnography is when the role of an ethnographer is made explicit in data analysis and is thus examined amidst cultural expectations that are constantly affecting him or her (Wilson, 2001, p. 566). According to Davies (2008, p. 94), this contributes to transparency in interpreting human interactions and engagements through empirical reasoning. An objective of this article is to use the approach as a primary framework in examining a change in using test scores in an English assessment program. In doing so, the terms humanism and humanistic will also be used, referring to those interactions and engagements and as opposed to such hard sciences as mathematics and physics. A primary research question is whether the change, especially as a result of sociopolitical and numerical assessments, can be justified using interpretive empiricism (cf. Anderson, 1996, p. 16ff.). Figure 1 depicts the investigation framework, in which the term assessment is used as a generic term referring to any measurement or activity wherein an entity or phenomenon is judged or estimated, producing tangible results such as opinions and scores.

Figure 1.

Investigation framework of the article.

In addition to transparency in interpretation, implementing a reflexive-ethnographic framework in investigating a change in test-score use can also be beneficial for two additional reasons. First, the present era is an era of change in relation to language testing and assessment (LTA) (Ryan et al., 2017, p. 436). While there are several studies that involve humanistic issues surrounding LTA (e.g., Maryns, 2015; McNamara et al., 2014), reflexive ethnography seems to have never been used as a study framework to account for test-score interpretation and use. In fact, LTA may be viewed as a discipline often associated with numbers, mathematics, and statistics. For example, educational measurement itself could often be represented by mere models and parameters such as , where a certain competence ( in the student model) is measured resulting in an observable score or quantifiable performance () (e.g., Mislevy, 2006, p. 286). Taking reflexive and eventually sociopolitical factors into account, the present study could thus be deemed to use an innovative approach to LTA research: numbers may count initially, but they will need to be interpreted and their suitability evaluated in light of sociopolitical factors. For this reason, the term evaluation refers in this article to when a value—statistical, political, or social—is placed on something.

Promoting evaluation of sociopolitical factors means that a humanistic element is added to LTA in general, and possibilities for a new view in test-score interpretation and use are also opened up in particular. This will be probable, especially when a power of explanation needs to be articulated (cf. Davies, 2008, p. 101). Despite the quantitative inclination of the field, using such interpretive approaches as reflexive ethnography may help to create a balanced view of the decision-making process in assessing language competence. Moreover, reflexive ethnography as a discipline is itself criticized for being idiosyncratic and lacking in generalizability (ibid.). Its implementation in LTA in this article may thus serve as another piece of applicability information to ethnographers. This could increase generalizability of the discipline because the more fields of study the approach is applicable to, the greater generalizability it has – more legitimate applications mean a bigger sample of observations in the universe of admissible observations, and hence the generalizability.

A second usefulness of using the present framework is an explicit reflection of an author's potential influence over research (Davies, 2008). In reflexive ethnography, a researcher's relationships with those being studied are to be examined explicitly. This is a case applicable in the present contexts, in which I served, inter alia, as an analyst of part of the assessment data that were used for informing the change. Not only does this mean time is given to questioning and reflecting on my own practices as a data analyst. It also agrees with the guideline about putting everything on the table in Kane (1990; 1992; 2002; 2004; 2012) argument-based approach to validation. Accordingly, scrutinizing my relationships with the stake-holding bodies involved would indicate a bare-all perspective in validity inquiries. During the process, conflicting interests could also be conveniently detected, rather than lurking in otherwise as hidden agenda (see, e.g., Pellatt, 2003, p. 33).

The authors of academic writings in general would seek to sound objective and formal (Hyland and Jiang, 2017). They also seek to distance themselves from the objects being studied as well as from the readers, for example, by not using conjunctive adverbs and direct questions (ibid.). However, reflexive ethnography involves “ongoing circuits of communication between researcher and researched” (Lichterman, 2017, p. 35). In light of the humanism-oriented framework in this article, it seems reasonable that some of my narratives and related issues will be presented as such. Rather than refraining from subjects related largely to me, those contents will be discussed without much restriction. This suggests that the approach of humanistic interpretation functions here as an introduction of the underlying reasons that may have been elsewhere influential but omitted from discussion to a systematic tackling.

The structure of this article is as follows. First, the contextual background of this study will be provided, so that the necessity to qualitatively explore the topic would be brought to light. Then the change to using test-scores in an assessment program will be outlined, along with the roles of reasoning and chains of inferences involved. This paper concludes with a call for more empirical-interpretive studies to justify LTA practices and actions based on them. This may include those using a reflexive-ethnographic framework for a transparent, post hoc disclosure of potential conflicts of interest and bias.

2. Research contexts

Given that the framework of exploration has been established, research contexts will be laid out. The first aspect of context is a paradigmatic one. Nikkel (2006, p. 14) evaluated a recent literature on LTA and contended that a large number of studies are invalid, one reason being a lack of qualitative aspect to provide a complete understanding of what is being studied. This is despite the view that qualitative approaches can be just as valid and reliable as quantitative ones (ibid.). Moreover, G. Fulcher (personal communication, December 19, 2013) stated that even though LTA would generally be seen as involved with numbers, the numbers all come to making sense and signification for interpretation and use of test scores (cf. also Messick, 1989 for score meaning as an overarching facet for validity). In other words, even if language testers may obtain numbers out of an assessment event, it is a sound interpretation and implication that would make those numbers meaningful or invalid. In fact, interpreting human interactions and engagements can produce a generalizable and post hoc claim of meaning and signification out of the world of phenomena (Anderson, 1996, p. 16ff.). This means that in research settings where extralinguistic and social factors are dealt with as in the present settings, interpreting those factors could contribute meaningfulness and accountability to changes. On this account, that a humanistic, interpretivist element is lacking and should be added to LTA is a first context.

In addition to the paradigmatic significance, the other aspect of context is the sociopolitical one where this investigation takes place. In the overall picture, my School has recently been engaging in a curriculum revamp. Normally due every five years, the revamp is part of the requirements set by the Ministry of Education, following the Plan−Do−Check−Action (PDCA) model for an outcome-based education. A coincidence is that a new president of the University has also just taken his role, implementing a re-profiling policy throughout. Depicted in Figure 2 (with a Thai text on top of the online pdf document reading ‘A development plan for Suranaree University of Technology, 2018–2021’) (Suranaree University of Technology, 2017), the policy is framed and made public online for the purpose of public relations.

Figure 2.

Re-profiling plan for the university administration.

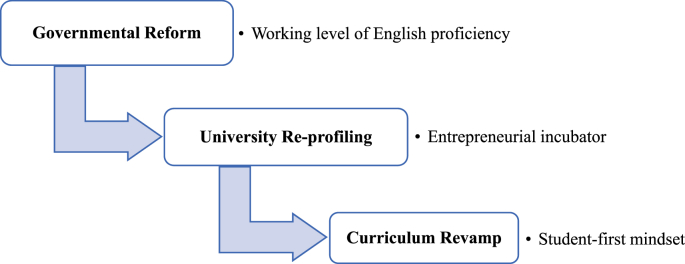

In addition to this reprofiling policy, there is also a reform on the national level put in place by the Thai government. It introduces a nationwide reform requiring that university graduates should achieve a working level of English proficiency (Ministry of Education, 2016). Figure 3 portrays this amidst a hierarchical change, and elaboration will follow.

Figure 3.

A hierarchy of requirements for an educational change.

On the top level of Figure 3, the government, albeit then an interim one run by a military junta, is in need of tangible actions. After being pressured by, for example, a low national score on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) Reading Test (Fredrickson, 2016; Kenan News, 2015; Ramangkul, 2016) and low national scores on the university entrance English examinations for many consecutive years (Jessadapatragul, 2014), it needs to show to the public that much is being done. Coming across as an informal yet powerful evaluation, the necessity could be mediated by the social network and the media (Naewna, 2013; Sabpaibtoon, 2017), especially considering that the junta is in expectancy to get elected and serve another term as the Prime Minister (Crispin, 2018). Also recapitulated in Figure 3, one of the most influential related works is issuing a statute requiring that all the graduates of the undergraduate level should master a proficiency that meets the working standards for English use. The statute has a far-reaching impact, which will be discussed subsequently.

Underneath the level of central governance in Figure 3 where the government is assessed by the public is the university level. The situation is that the University Council has recently appointed a new president of my University. In turn, rather than sitting idle, the president would feel compelled to make a difference. Overviewed earlier, one of the policies is a university re-profiling: The University would serve as an entrepreneurial incubator, making the graduates a readier workforce for the business sector. On the one hand, considering that such a re-profiling implies a change on the surface level, it may not be deemed as extensive as, for example, a structural reform. On the other hand, this could be considered a discernible development because it may arguably a) affect how the society perceives the University, and b) personalize the transitional process and the results thereafter as attributed to the new executive. Communicated and reinforced to the university community, the policies appear in the form of branding walls and mission statements on campus as well as memorabilia for the staff. Figure 4 portrays such appearance, with emphasis on the re-profiling policy.

Figure 4.

Branding walls and memorabilia for the re-profiling policy: (clockwise) 1. a cap; 2. an organizer; 3.–4. branding walls; 5. a shopping bag; 6. a calendar.

Given the aim of becoming an entrepreneurial university that moves towards social enterprise, English is viewed as an essential tool that would give a cutting edge to the university graduates. In line with the statute by the government, the policy is that all the students entering the University in 2017 and later must achieve English proficiency no lower than the B1 level in a Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR)-based assessment and the like when they file for graduation. This means that, inter alia, whatever level the students have of their English proficiency at the entrance to the University, they would need to be educated somehow to B1 and higher. Considering the low national English scores mentioned earlier, the aim seems to require much effort on the pedagogical part and hence considerable resources to draw on from the viewpoint of educational administration. In fact, outlined in Figure 5, the majority of incoming students in 2017 are found to have an A1 English proficiency (Center for Educational Services, 2017). This suggests that considerably more needs to be done on the University's part as well as by means of the students' own efforts before the level of B1 desired could be achieved overall. In sum, an argument may be that the president's performance would be assessed from, for one thing, the extent to which the university graduates could attain the level of English proficiency that is encouraged by the government and fashioned to the CEFR scheme.

Figure 5.

Number of students starting the first year across CEFR levels.

The closest level to me is the departmental level. The faculty's performance would be assessed by the university and eventually by the university community for the purposes of accountability and contract renewal. For example, when the scores of the students in one English course are evaluated for grades (e.g., A, B+, F), the overall picture of the number of students in each grade category will have to be reported together with those of the other English courses offered by the School. Accordingly, the assessors in this level would include the university president and the students, who may complain of, for example, an unfair grading and a disproportionate distribution of grades. Moreover, communications of the re-profiling policy are sent out on campus in multiple forms, as depicted in Figure 4. Given this, it seems that expectations are set up for the university community and eventually the faculty to realize.

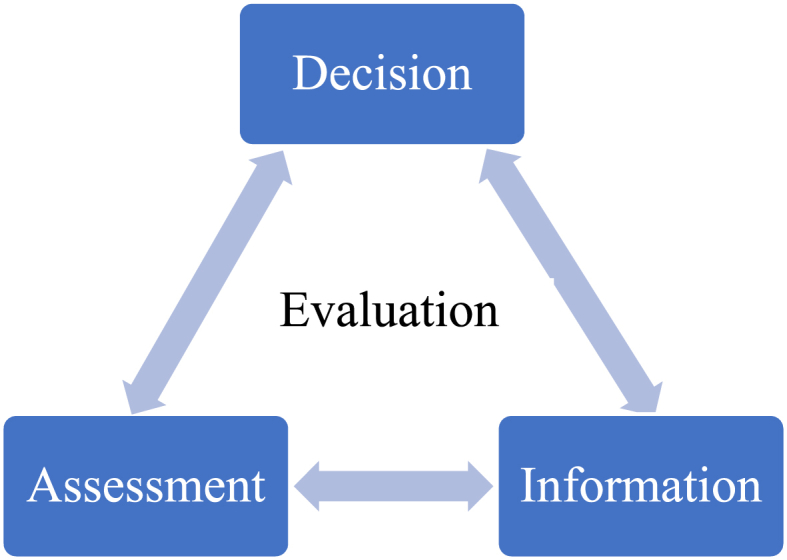

Regarding the curriculum revamp brought up in Figure 3, the University would wish to see an effective curriculum implementation by the School. This would enable the students’ achievement of the English proficiency level required and an accurate assessment of it. For example, should the curriculum recently revamped produce students with a very low level of English proficiency throughout, then either the curriculum itself or the implementation may have gone wrong. On this account, an assessment activity or its prospects in my current contexts could be argued to be drivers of change, with the stakeholders functioning as the assessors. Figure 6 depicts the centripetal force of evaluation and language assessment from the government level to the current one.

Figure 6.

Centripetal force of assessment.

In conclusion, the government's performance is assessed by the public; the University President's performance is to be assessed by the Council and the university stakeholders; and the School's performance is assessed by the students and eventually the university. In light of these descriptions of a multi-level change, it may be synthesized that some form of assessment takes place in all levels of change and drives into action the authorities or those responsible for an educational body. In Figure 6, this is visualized with a) the government's statute functioning as a superior change driver, b) the University President's policy as an intermediate one, and c) the curriculum revamp as an inferior change driver. Therefore, implementing educational policies and the like as driven by potential assessment could be deemed to be an overarching theme and a sociopolitical aspect that hallmarks the overall significance of this study. In other words, one core topic emerges from examining the contexts of this paper: Assessment has an impact on those involved, making them struggling to meet the stakeholders' evaluative expectations.

Before proceeding to the next section that tackles a change in using test-scores in an assessment program, the roles of the author as appeared in Figure 6 will be dealt with. Not only does this make a pursuit of the framework experimented in this study, but my involvement, or a lack thereof, in the multiple layers of assessment can also be established for the sake of transparency. At the innermost level, I am an analyst of the quantitative data that are the test scores used for informing the change focused on (presented in the next section). While a few of the scores are of the students in my class, the purpose of the score analysis and the research ethics dictate that the scores are to be analyzed in their aggregate and presented as such. Without any student referred to individually, preferences or bias could be deemed to be minimal.

At the inner level of the assessment force in Figure 6 is the curriculum revamp. The revamp had taken place before I started working for the School. A lecturer teaching the courses under this curriculum, some of my responsibilities include aligning the course content I teach to the expected learning outcomes of the curriculum as well as grading the students' performance and learning achievement accordingly. Given this, the curriculum recently overhauled could be deemed to function as a guide that I need to follow, whilst my freedom to divert from it could only happen through suggesting amendments for the next revamp, which will occur in approximately four years. Therefore, an inference related to the author's roles in this inner level is that my use of the present curriculum is resulted from the then ongoing assessment by the stakeholders that had brought the previous curriculum to the present revamp. While I may contribute to changes in the next round of curriculum amendment, my role in the present curriculum is of a follower rather than a gamechanger.

At the level superior to the School's curriculum revamp is the one aiming for a university re-profiling. I am a staff member of the university, teaching English to undergraduate students. On the one hand, my contribution to the current level of assessment force is understood to include joining the teamwork that drives the overall English performance of the students to the B1 level of CEFR, the minimum level of English proficiency strategically pursued for the reprofiling. Still, because I am not part of the University's executive team, it seems that my role in the University's reprofiling could be deemed limited to practical implementation, rather than planning.

At the uppermost level of the centripetal force of assessment in Figure 6 is the CEFR-referenced English educational policy legislated by the Ministry of Education. Given its legality, my role as a lecturer would be restricted to observing the statute by the teaching role. Doing so would also be commensurate with following the University's reprofiling. Yet, it is worth highlighting that the legislature took place only in 2016, and its resultant implementation of the English standard orientation is nothing but going to uncharted waters. Accordingly, in light of my roles in the multiple layers of assessment force considered thus far, it seems fair to conclude that the sociopolitical contexts of this paper are for me to be a driver of practical change, and a conflict of interest in this investigation could be considered minimal. Also, this study is exempted from ethical approval at my University, because there is no human subject involved in data analysis and all the data used for analysis is secondary.

3. Assessment-driven change: a series of actions

Introduced in the previous section, enabling the students to achieve a working level of English proficiency is a commitment demanding considerable resources of the organizations of all the levels involved. For example, a mission of my School is to educate the students through the current curriculum such that they achieve the proficiency required by the University. One of the investments made for the purpose is to assess the new students with an online placement test provided commercially by a private company. The aim is to allocate the resources to those who really need them and let those already equipped with the mastery automatically obtain the corresponding grades and enjoy the benefits of saving money and time. Table 1 shows part of the report of raw scores from the test. Categories in accordance with the CEFR are also provided alongside the scores by the company. The score results from the placement test is used for constructing the English language profile of the students of the university and for deciding which English course each student could take, which will be described subsequently.

Table 1.

Example of a score report from the online placement test.

| ID | Score | Time Taken | CEFR | Date Taken | Status | Score | Time Taken | Use of English | Score | Time taken | Listening |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 0:51 | A1 | 19/7/2017 | Normal | 1 | 0:18 | A0 (High) | 6 | 0:33 | A1 |

| 2 | 29 | 0:41 | A2 | 19/7/2017 | Normal | 22 | 0:24 | A2 | 36 | 0:16 | A2 |

| 3 | 6 | 0:46 | A1 | 19/7/2017 | Normal | 1 | 0:18 | A0 (High) | 11 | 0:28 | A1 |

| 4 | 3 | 0:50 | A1 | 19/7/2017 | Normal | 5 | 0:22 | A1 | 0.9 | 0:27 | A0 (High) |

| 5 | 1 | 0:42 | A1 | 19/7/2017 | Normal | 0.9 | 0:14 | A0 (High) | 1 | 0:28 | A1 |

| 6 | 7 | 0:47 | A1 | 19/7/2017 | Normal | 2 | 0:21 | A1 | 13 | 0:26 | A1 |

| 7 | 38 | 0:56 | A2 | 19/7/2017 | Normal | 53 | 0:34 | B1 | 22 | 0:22 | A2 |

To the students who take the placement test, scores and levels are given out, from A1 (beginner) to C2 (proficient user). These levels are claimed to have concordance to the actual CEFR, which is presented in Table 2. Under this testing program, inter alia, those who obtain scores of the A2 level can skip the first two English courses offered by the School, English I & II. In other words, this program allows the students who score over 20 in the placement test to automatically pass the first two foundation English courses.

Table 2.

CEFR-based level of the Oxford Online Placement Test (OOPT) (Pollitt, 2014, p. 9, adapted).

| Score Range | CEFR Level |

|---|---|

| 0 | < A1 |

| 1–20 | A1 |

| 21–40 | A2 |

| 41–60 | B1 |

| 61–80 | B2 |

| 81–100 | C1 |

| >100 | C2 |

However, the challenge at that time was that the aforementioned criterion was set somewhat arbitrarily based on the face value of the coursebook content used for English III. Somewhere in between the A2 and B1 levels, its genesis is shown in Table 3, in which the students getting the A2 level in the placement test may be interpreted as having the proficiency needed for the English III coursebook. Due to the time constraint caused by the start of the then upcoming academic year, the School could not afford time to carry out any validation study in favor of the criterion before it was actually implemented. The scores and the CEFR-oriented levels produced by the testing company, which have been shown in Table 1, had to be taken as they stood. In fact, no study had been performed about the potential results and consequences of the very administration of the placement test. For example, whether the test can be useful for benchmarking the input students before they take the exit test and graduate may be said to completely lack validity studies up to the present. Accordingly, the issue of equating the CEFR-oriented levels to the content of the School's English courses is likewise an uncharted water amidst the force of assessment and the time frame of educational administration that continues steadily from term to term.

Table 3.

Comparing the Placement-Test score interpretations and the content level of English III.

| Oxford Online Placement Test's (Pollitt, 2014) Interpretation |

English III coursebook Read This! 2 (Mackey and Savage, 2010; British Book, 2011) level | |

|---|---|---|

| Score Range | CEFR Level | |

| 21–40 | A2 | A2–B1 |

| 41–60 | B1 | |

In light of the exemption implemented, some of the teaching staff noticed a discernible difference in the proficiency levels between those who had just been exempted from studying the first two foundation courses and those who had studied them in a normal sequence of English courses. This led to an internal appraisal of the situations, inquiring if there should be a change in the criterion and details of the exemption program. However, given that the program was ongoing and any change to it might cause unfairness to those who had not gotten to bypass to English III, a way out then was to collect more information, especially concrete one, that would be able to confirm or dispute the teachers’ observation. Figure 7 outlines this step of performance observation.

Figure 7.

Chain of assessment events for adjusting an exemption program.

In addition to the teaching staff's observation about the exempted students' performance, the School also performs a risk assessment. A key question is whether the School can really change or modify the criteria in relation to the placement-test program, particularly when some of the students who have been qualified for the exemption already take the exemption route—aka. the fast-tracking—to later English courses while some others do not yet do so. Most importantly, it seems rational to presume that changes in criteria cannot be treated lightly or changed any time at whim. Or else, it would be the School's reputation and accountability that would be at risk. Therefore, it is decided that concrete evidence needs to be supplied in order for the criteria to be adjusted.

In search of evidence to support changes in the criteria of the placement-testing program, scores of those students who have been exempted to English III are selected. Considered a promising source of ad hoc verification of the status quo yet arbitrary criterion, they are separated, inter alia, into the scores of the upper band of the A2 level and those of the lower A2 band. The reason is that if these two groups perform significantly differently, then those in the lower band should not have been exempted to English III in the first place. Figure 8 shows the results of analysis of the test scores across the first two terms of the 2017 academic year.

Figure 8.

Correlation of scores from the CEFR-based placement test and English III: 1. correlation in Term 1 of the 2017 academic year; 2. correlation in Term 2 of the 2017 academic year.

In Figure 8, the regression lines of the correlated scores have a positive trend in both Terms 1 and 2. It may be interpreted that the scores of those who have been exempted with the upper band of the A2 level are likely to be higher than those of the lower band. Moreover, because this pattern can be observed across the terms, the former group is likely to systematically score better than the latter group. An inference is thus that categorizing the students based on the score ranges and bands provided by the private company seems insufficient. Another inference is that the observation by some of the teaching staff is also likely to be valid. In order to confirm these inferences, the scores of the two groups under discussion are examined further in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4.

English III score descriptions of Terms 1 and 2.

| Proficiency Category | Term 1 (N = 238) |

Term 2 (N = 224) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Students with the highest CEFR-based Placement Test Score in A2 level (n = 100) | 78.79 | 9.47 | 79.21 | 7 |

| Students with the lowest CEFR-based Placement Test Score in A2 level (n = 100) | 70.24 | 7.88 | 76.3 | 5.73 |

Table 5.

English III score comparison: High-CEFR vs. low-CEFR A2 students.

| Term | English III Scores Compared Based on the A2 Higher-Band and Lower-band of A2 | Levene's Test for Equality of Variances |

T-test for Equality of Means |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | ||

| Term 1 | Equal Variances Assumed | .025 | .874 | 6.934 | 198 | .000* |

| Equal Variances Not Assumed | 6.934 | 191.68 | .000* | |||

| Term 2 | Equal Variances Assumed | 4.70 | .031 | 3.21 | 198 | .002* |

| Equal Variances Not Assumed | 3.21 | 190.62 | .002* | |||

* Significant at p = .01.

In Table 4, the scores of the upper band are found to be higher than those in the lower band across the two terms. This finding is all the obvious, considering that the two groups are classified by either the upper-band scores or the lower-band ones in the first place. In Table 5, the scores of the upper-band groups (M = 78.79 and 79.21, SD = 9.47 and 7) are found to significantly differ from those in the lower-band groups (M = 70.24 and 76.3, SD = 7.88 and 5.73; t (6.93 and 3.21), p = .01). It may thus be inferred that the difference seems systematic and, given that it happens in two consecutive terms, this pattern is likely to have reliability. The consequence of these score analyses is the conclusion that the teacher's observation seems to have validity, the risk from amendments to the score criterion is reduced, and the criterion should be changed and informed to the stakeholders in the following academic year.

With regard to the current line of inquiry, it may be stated that the series of activities described thus far is all involved with assessment. That is, the teacher's observation involves an assessment of the face value of the performance produced by different groups of the students. The situational weigh-in involves a sociopolitical assessment of the stakeholders' benefits and risks of an abrupt change. A result of these two assessment activities is that a test-data analysis becomes obligatory, so that the change would be an informed decision. In fact, as introduced at the beginning of this article, the present study is the first to justify a change in using test-scores in an assessment program by means of reflexive ethnography. This means that the chain of inferences in relation to the change in the assessment program starts with an impression made based on some teachers' observations of the students' performance during teaching, and ends with an actual change after being informed by results of test analyses. Table 6 portrays some of the changes caused by these assessments and inferences. For example, those who get 21–30 in the OOPT can only skip English I and will have to study English II onwards. They could no longer skip both English I and English II, as a result of the investigation in Figure 8, and Tables 4 and 5. In other words, the cut-off point for English III now has been upped from 21 to 31 and higher for the scores in the OOPT.

Table 6.

Change of exempted courses.

| CEFR Level | Score | Exempted Course | Course to Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| A0 | <1 | No course exempted | English I–V |

| A1 | 1–20 | No course exempted | English I–V |

| A2 | 21–30 | English I exempted | English II–V |

| 31–40 | English I & II exempted | English III–V | |

| B1 | 41–60 | English I–III exempted | English IV & V |

4. Conclusion and implications

In this article, impacts of assessment events on bodies of organization and an assessment program have been evaluated. It is determined that while qualitative argumentation deserves a significant place in LTA, using multiple sources and justifying use of the information from those sources can be equally important for an informed decision-making. Table 7 summarizes the sources of information presented in this paper in accordance with Messick (1989) validity matrix.

Table 7.

Putting the sociopolitical entity to the validity framework.

| Validity Facet | Test-score Interpretation | Test-score Use |

|---|---|---|

| Evidential | Teacher observation: Some exemption students not performing up to the standard of English III | Utility of a placement test: Somewhat undiscriminating classification of the commercially available scale for English proficiency |

| Consequential | Resultant scores: Exemption students having too wide a gap in terms of English proficiency levels | Sociopolitical stakes: The School's reputation and commitment to the university community regarding CEFR-standard realization |

Although approaches in LTA such as Kane (1990; 1992; 2002; 2004; 2012) argument-based approach to validity inquiries are never associated formally with reflexive ethnography, using the framework in this article would mean that a more human side is added to LTA in general and a new piece of applicability information is fed to ethnographers about another utility of their existing approach in particular. In the latter case, this is when generalizability of the approach becomes greater, considering that cases of its applicability in the universe of admissible observations increase. Depicted in Figure 9, the finding that assessment is likely to be ubiquitous in all facets of the test-score interpretation and use and in their changes allows an inference that evaluation also occurs everywhere. Evaluation is to judge if the very results of testing, measurement and assessment meet a standard or a certain set of standards and so is interpretive in nature. This can be where quantitative LTA and qualitative humanism converge.

Figure 9.

Drive of assessment for decision making.

Traditionally, LTA, including its superordinate discipline of educational measurement, would involve seeking a representation of our understanding of the competence or performance that might vary in accordance with differing parameters such as task content and properties of test items (Mislevy, 2006: 286–7). Numerical statistics such as reliability are still gold standards for data analyses in the field, as evidenced by, for example, its wide use in an LTA research colloquium (cf. ILTA, 2015). However, a definition of validity goes:

[A]n integrated evaluative judgment of the degree to which empirical evidence and theoretical rationales support the adequacy and appropriateness of inferences and actions based on test scores or other modes of assessment” (Messick, 1989: 13, italics in original)

Messick's definition of validity highlights importance of inferences and actions. No emphasis seems to fall only on quantitative data. Accordingly, the discussion in this study reiterates the significance of Messick's definition of validity and instantiates the sociopolitical impacts embedded in Messick's construct-validity progressive matrix. On the one hand, the findings in this article are not meant to diminish the parameter-based paradigm, but to enrich it. On the other, it is found that an assessment-driven change in using English test scores can be justified with empirical reasoning under a reflexive-ethnographic framework of investigation. Accordingly, this study calls for more empirical-interpretive studies to justify assessments and actions in LTA based on them. Argued in this article, bringing in qualitative considerations to LTA would create balanced and innovative views in the field and an increased transparency.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Kunlaphak Kongsuwannakul: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgments

I would like to say a big thank you to my University and School of Foreign Languages. They funded the presentation of a previous version of this article at a conference in Istanbul, as well as allowed me to access the test-score data, which has proved to be very useful in the analyses. Also, gratitude is expressed to the anonymous reviewers and the editor. The comments are just as constructive, enabling me to better articulate the content and its potential implications to the audience.

References

- Anderson J.A. Guilford Press; New York: 1996. Communication Theory: Epistemological Foundations. [Google Scholar]

- British Book . Academic Courses; 2011. Textbook Read This! 2 Student’s Book.https://www.britishbook.ua/detail/read-this-2-student-s-book-with-mp3-available-online/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Educational Services . Suranaree University of Technology; Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand: 2017. 2017 Oxford Online Placement Test Score Reports. [Unpublished data set] [Google Scholar]

- Crispin S.W. Asia Times; 2018. Blind Spots in Prayuth's Election Promise.http://www.atimes.com/article/blind-spots-prayuths-election-promise/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Davies C.A. second ed. Routledge; Oxon, UK: 2008. Reflexive Ethnography: A Guide to Researching Selves and Others. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson T. Bangkok Post; 2016. Pisa Test Rankings Put Thai Students Near Bottom of Asia: Scores below Asian Peers, Global Average.https://www.bangkokpost.com/learning/advanced/1154532/pisa-test-rankings-put-thai-students-near-bottom-of-asia Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland K., Jiang F. Is academic writing becoming more informal? Engl. Specif. Purp. 2017;45:40–51. [Google Scholar]

- ILTA . 2015. Language Testing Research Colloquium (LTRC) 2015. Toronto, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Jessadapatragul C. Daily News; 2014. How to Study English for an Admissions Test.https://dailynews.co.th/Content/Article/229862/_%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B5%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%A0%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kane M.T. Iowa City: The American College Testing Program; 1990. An Argument-Based Approach to Validation. [Google Scholar]

- Kane M.T. An argument-based approach to validity. Psychol. Bull. 1992;112(3):527–535. [Google Scholar]

- Kane M.T. Inferences about variance components and reliability-generalizability coefficients in the absence of random sampling. J. Educ. Meas. 2002;39(2):165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kane M.T. Certification testing as an illustration of argument-based validation. Measurement. 2004;2(3):135–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kane M.T. All validity is construct validity. or is it? Meas. Interdiscip. Res. Persp. 2012;10(1–2):66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kenan News . Kenan Institute Asia; 2015. Thai Education System Fails in Latest PISA Tests: Chevron Enjoy Science Advocates STEM Education to Solve Problem.https://www.kenan-asia.org/thai-education-system-fails-in-latest-pisa-tests-chevron-enjoy-science-advocates-stem-education-to-solve-problem/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIvIO30MWt3AIVhx0rCh283QhbEAAYASAAEgIvsvD_BwEed Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Lichterman P. Interpretive reflexivity in ethnography. Ethnography. 2017;18(1):35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey D., Savage A. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2010. Read This! Level 2 Student’s Book: Fascinating Stories from the Content Areas. [Google Scholar]

- Maryns K. The use of English as ad hoc institutional standard in the Belgian asylum interview. Appl. Ling. 2015;38(5):737–758. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara T., Van Den Hazelkamp C., Verrips M. LADO as a language test: issues of validity. Appl. Ling. 2014;37(2):262–283. [Google Scholar]

- Messick S. Validity. In: Linn R.L., editor. Educational Measurement. third ed. American Council on Education; Collier Macmillan; New York: 1989. pp. 13–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education . Ministry of Education; Bangkok: 2016. Higher Education Commission Statute: Reform Policy on English university Standards [Statute in Thai] [Google Scholar]

- Mislevy R.J. Cognitive psychology and educational measurement. In: Linn R.L., editor. Educational Measurement. fourth ed. Greenwood; Arizona: 2006. pp. 257–305. [Google Scholar]

- Naewna . 2013. Gurus Warn Mainstream media: Don't Be Used by Social media, Always Scrutinize the Source. Naewna.www.naewna.com/politic/80251 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkel W. University of Manitoba; Winnipeg, Canada: 2006. Language Revitalization in Northern Manitoba: A Study of an Elementary School Cree Bilingual Program. (M.Ed. thesis) [Google Scholar]

- Pellatt G. Ethnography and reflexivity: emotions and feelings in fieldwork. Nurse Res. 2003;10(3) doi: 10.7748/nr2003.04.10.3.28.c5894. http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A100544137/AONE?u=uninet20&sid=AONE&xid=5cfb0126 Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt A. Oxford English Testing; Oxford: 2014. The Oxford Online Placement Test: the Meaning of OOPT Scores.https://www.oxfordenglishtesting.com/uploadedfiles/buy_tests/oopt_meaning.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ramangkul W. 2016. PISA Exam.http://www.matichon.co.th/news/400844 [in Thai]. Matichon. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan A.M., Reeder M.C., Juliya G., James G., Ilke I., Dave B., Xiang Y. Culture and testing practices: is the world flat? Appl. Psychol. 2017;66(3):434–467. [Google Scholar]

- Sabpaibtoon P. Bangkok Post; 2017. Prayut Threatens media Outlets with Strict Cyber Law.https://www.bangkokpost.com/news/politics/1364587/prayut-threatens-media-outlets-with-strict-cyber-law Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Suranaree University of Technology . Suranaree University of Technology; 2017. Development Plan of Suranaree University of Technology, 2018–2021 [in Thai]http://web.sut.ac.th/dpn/document/plan/PLAN%20SUT-61-64.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T.D. Reflexive ethnography: a guide to researching selves and others [Review of the book Reflexive ethnography: a guide to researching selves and others, by Charlotte Aull Davies] Am. Anthropol. 2001;103(2):566–567. [Google Scholar]