Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pancreatic solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare neoplasm of intermediate biological potential. So far, only 22 cases have been reported since 1999. All the cases, except one, exhibited benign features. Here, we report the first case of malignant pancreatic SFT with typical Doege-Potter syndrome, along with the clinical and pathologic evidence of its systemic metastasis.

CASE SUMMARY

The patient was a 48-year-old man with a 1-year history of pancreatic and liver masses and refractory hypoglycemia. Increased uptake of the tracer fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) was found in the liver and bones by fluorine-18 FDG positron emission tomography/computed tomography. After multidisciplinary discussion, a distal pancreatectomy procedure was performed, and histological examination showed a lesion composed of abundant heterogeneous spindle cells with localized necrosis. On immunohistochemistry evaluation, STAT6 was found to be diffusely expressed in the tumor. Based on the overall evidence, the patient was diagnosed with malignant pancreatic SFT with liver and bone metastases.

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of malignant SFT requires comprehensive evidence including clinical, immunohistochemistry, and histological features. This case may be presented as a reference for diagnoses and management of malignant pancreatic SFTs with systemic metastasis.

Keywords: Solitary fibrous tumor, Pancreas, Malignant, Doege-Potter syndrome, Case report

Core tip: Solitary fibrous tumor is now considered as a fibroblastic mesenchymal neoplasm of intermediate biological potential, and it rarely occurs in the pancreas. Here, we report a case of malignant pancreatic solitary fibrous tumor with systemic metastasis, review the literature, and discuss its biological features, diagnosis, and prognosis evaluations.

INTRODUCTION

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT), first described in 1870, was established as a pleural neoplasm by Klemperer and Rabin in 1931[1]. This tumor is commonly found in serosal membranes, the dura of the meninges, and deep soft tissues. It is now recognized as a type of fibroblastic mesenchymal neoplasm of intermediate biological potential characterized by the pathognomonic NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion[2]. Only a few reports on malignant pancreatic SFT have been previously published. We present herein the first case of malignant pancreatic SFT with typical Doege-Potter syndrome and, hepatic and bone metastases.

CASE PRESENTATION

Primary complaints

A 48-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with 1-year history of pancreatic and liver tumors. The tumors were accidentally found when the patient went to a local hospital after a sudden incidence of fainting. It is noteworthy that he reported of recurrent incidences of hypoglycemia, however, there was no history of any endocrine disease.

History of past illness

His medical history showed that he had been treated eight times for metastatic liver tumor by transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and once by radioactive seed implantation. Five years before presentation, he had undergone an excision of a tumor of the right pterygopalatine fossa.

Physical examination

Physical examination showed no other positive findings except that the liver was enlarged and palpable.

Laboratory and imaging examinations

Laboratory investigations showed an abnormal hemogram, including hemoglobin of 123 g/L (reference range: 131-172 g/L), neutrophils 72.8% (reference range: 50%-70%) and lymphocytes 10.8% (reference range: 20%-40%). The results of liver and kidney function were normal. The levels of serum tumor markers (CEA, CA 19-9, CA 12-5, and AFP) were all within normal limits.

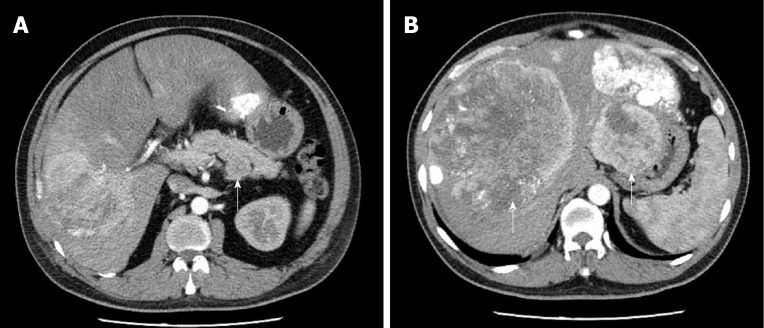

Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the abdomen showed a 4.7 cm well-defined mass located in the lower posterior part of the body of the pancreas (Figure 1A). Non-uniform enhancement was observed from the arterial to portal venous phase. Meanwhile, multiple nodules and masses of various sizes were seen in the liver (Figure 1B). The largest one was located in the segment VIII of the liver with a diameter of about 15.9 cm. No obvious dilatation of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts was observed.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography imaging of the abdomen. A: A 4.7 cm × 4.4 cm mass (white arrow) located in the body of pancreas. Non-uniform enhancement was observed from the arterial phase [computed tomography (CT) value = 68 Hu] to portal venous phase (CT value = 59 Hu); B: Numerous liver metastatic tumors (white arrows). Enhanced scanning showed irregular enhancement and the largest one located in segment VIII measured 15.9 cm.

Pancreatic magnetic resonance (MR) imagining also confirmed a hypervascular tumor located in the body of the pancreas and multiple tumors located in the liver. Those tumors were hypointense on T1-weighted MR images and hyperintense on T2-weighted MR images.

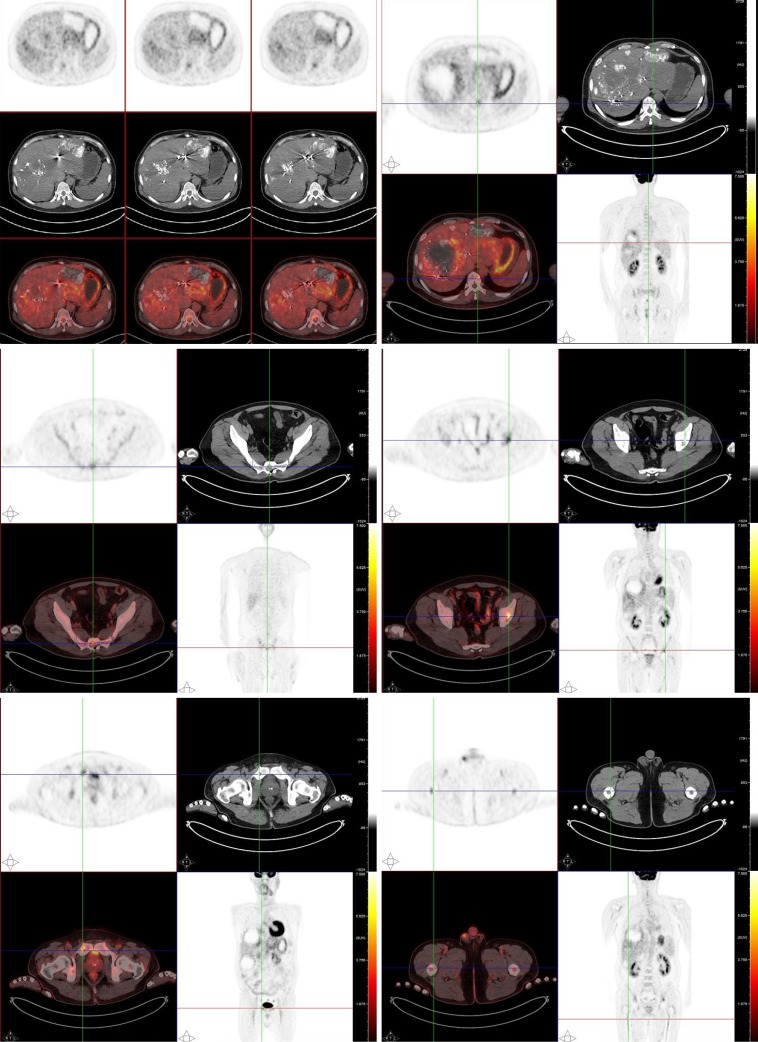

For a complete preoperative evaluation, fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG PET/CT) was performed. Images from the PET/CT revealed that both the pancreatic and the metastatic liver lesions had an increased uptake of the tracer FDG. Besides, the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, humerus, femur, scapulae, ribs, sacrum, and pelvis also showed heterogeneous FDG uptake (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Systemic fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan. The positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan revealed an increased uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose in the liver and heterogeneous fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in multiple bones.

Further diagnostic work-up

A liver biopsy guided by B-mode ultrasound confirmed that the tumor was an SFT/ hemangiopericytoma (Grade 2).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The patient was eventually diagnosed with a malignant SFT of the pancreas with Doege-Potter syndrome and metastases to the liver and bone.

TREATMENT

In order to improve the quality of life of the patient and control the growth of the mass, a distal pancreatectomy, involving the body and tail and splenectomy, was performed after a multidisciplinary discussion, and the metastatic neoplasm in the left lateral lobe of the liver was also resected.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

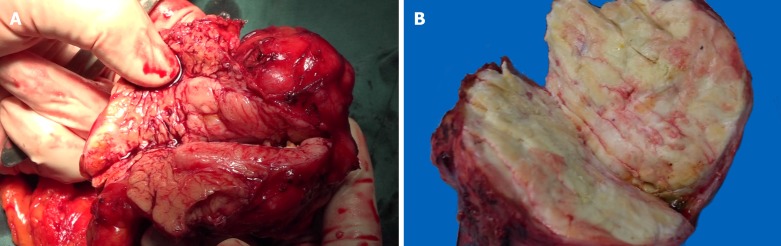

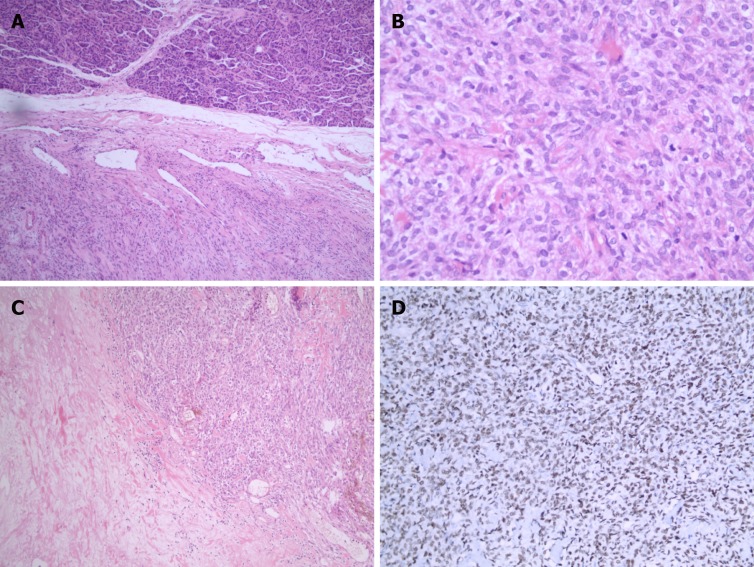

On gross examination, the pancreatic specimen measured 15 cm × 6 cm × 2 cm, which contained two well-circumscribed non-encapsulated masses. The larger lesion measuring 6.5 cm × 5 cm, had a soft fleshy cut surface containing hemorrhagic and necrotic areas (Figure 3A). Another metastatic lesion located in the left lobe of the liver measured 14 cm × 12 cm × 4 cm with a pale-yellow cut surface (Figure 3B). All the resection margins were free of tumor. On histopathological examination, it was found that the tumor was composed of abundant heterogeneous spindle cells (Figure 4A). A localized area of necrosis (Figure 4B) was visualized and there were 4-5 mitotic figures (Figure 4C) per 10 high-power fields (HPFs). Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of the resected tumor revealed that the tumor cells were diffusely positive for STAT6 (Figure 4D), CD34, CD31, Bcl-2, cell proliferation marker Ki-67, PHH-3, and D2-40, and negative for glial fibrillary acidic protein, S100, smooth muscle actin (SMA), Desmin, delay of germination 1, CD117, and receptor tyrosine kinase. The proliferation index of Ki-67 was observed to be above 10%. The patient’s postoperative recovery was uneventful. Furthermore, a transcatheter arterial chemoembolization procedure was also performed to eliminate the residual tumor of the right liver, and postoperative follow-up at 6 mo demonstrated good results (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Photographs of cut surface of surgical specimens. A: A soft mass located in the body of pancreas. Hemorrhage and necrosis changes can be seen in the cut surface; B: The pale-yellow cut surface of the hepatic metastasis.

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of histologic and immunohistochemical staining. A: Various atypical spindled cells irregularly arranged in the stroma [hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining; magnification: ×50]; B: Histologic demonstration of mitotic activity (HE staining; magnification: ×200); C: Presence of necrosis (HE staining; magnification: ×100); D: Immunohistochemical staining for STAT6 showed diffused positivity in tumor cells (magnification: ×100).

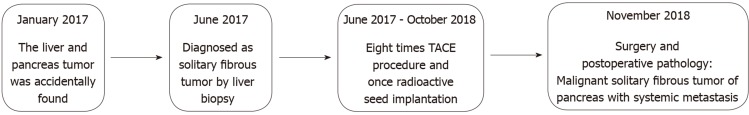

Figure 5.

Timeline. A brief summary of the patient’s medical history is presented. TACE: Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

DISCUSSION

SFTs are now considered to occur anywhere in the body, but the pancreatic fibrous tumor is still rarely recorded in the literature: only 22 cases have been reported since 1999 (Table 1). The vast majority of the cases presented with benign features, and only one case was defined as being malignant, based on its histological features[3]. The case we present here, to our knowledge, is the first malignant pancreatic SFT with clinical and pathological evidence of liver and bone metastases.

Table 1.

Clinical features of pancreatic solitary fibrous tumors

| Ref. | Age/Sex | Chief complaint(s) | Size (cm) | Location | Arterial-CT | Venous-CT | T1-MRI | T2-MRI | Tumor marker |

| Lüttges et al[13] | 50/female | Incidental | 5.5 | Body | Enhanced | Enhanced | NA | NA | Negative |

| Chatti et al[14] | 41/male | Abdominal pain | 13.0 | Body | Enhanced | Enhanced | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Negative |

| Gardini et al[15] | 62/female | Abdominal pain | 3.0 | Head | Enhanced | Enhanced | NA | NA | Negative |

| Miyamoto et al[10] | 41/female | Abdominal pain | 2.0 | Head-body | Enhanced | Enhanced | NA | NA | Negative |

| Kwon et al[16] | 54/male | Incidental | 4.5 | Body | Enhanced | Enhanced | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Negative |

| Srinivasan et al[17] | 78/female | Back pain, weight loss | 5.0 | Body | Enhanced | Enhanced | NA | NA | Negative |

| Chetty et al[18] | 67/female | Incidental | 2.6 | Head | Enhanced | Enhanced | NA | NA | Negative |

| Ishiwatari et al[19] | 58/female | Incidental | 3.0 | Head | Enhanced | Enhanced | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Negative |

| Sugawara et al[20] | 55/female | Incidental | 7.0 | Head | Enhanced | Enhanced | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Negative |

| Azadi et al[6] | 57/male | Incidental | 3.1 | Tail | Enhanced | Enhanced | Hypointense | Hyperintense | |

| Santos et al[21] | 40/male | Incidental | 3.0 | Body | NA | NA | NA | NA | Negative |

| Tasdemir et al[11] | 24/female | Epigastric pain | 18.5 | Head | Enhanced | Enhanced | NA | NA | Negative |

| van der Vorst et al[22] | 67/female | Abdominal pain | 2.8 | Head | Enhanced | NA | NA | NA | Negative |

| Chen et al[23] | 49/female | Abdominal pain | 13.0 | Head | Enhanced | Enhanced | NA | NA | Negative |

| Hwang et al[24] | 53/female | Incidental | 5.2 | Head | Enhanced | Enhanced | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Negative |

| Baxter et al[25] | 54/female | Abdominal pain | 3.5 | Head | NA | N.A | NA | NA | CEA, CA19-9 |

| Estrella et al[3] | 52/female | Obstructive jaundice | 15.0 | Head | Hetero-geneous | Hetero-geneous | NA | NA | Negative |

| Han et al[26] | 77/female | Jaundice | 1.5 | Head | Enhanced | Enhanced | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Negative |

| Murakami et al[27] | 82/male | Hypokalemia, hypertension, edema | 6.0 | Tail | Hetero-geneous | Hetero-geneous | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Negative |

| Paramythiotis et al[28] | 55/male | Abdominal pain | 3.6 | Body | Enhanced | Enhanced | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Negative |

| Spasevska et al[29] | 47/male | Epigastric pain and jaundice | 3.5 | Head | Enhanced | Enhanced | N.A | N.A | CA19-9 |

| Oana et al[30] | 73/male | Abdominal discomfort | 7.5 | Head | Enhanced | Enhanced | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Negative |

| Current case | 48/male | Hypoglyce-mia | 6.5 | Body | Enhanced | Enhanced | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Negative |

CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; NA: Not applicable.

Until now, there is no one comprehensive definition of malignant SFTs. According to the previous literature, abdominal pain is the most common presentation of clinical syndrome in a pancreatic SFT (10/22 cases, 45.45%), followed by an incidental abdominal mass (8/22 cases, 36.36%) and obstructive jaundice. Infrequently, patients may present with paraneoplastic syndromes. The clinical manifestations were commonly refractory and recurrent hypoglycemia, which is the main clinical characteristic of Doege-Potter syndrome. Increased secretion of a pro-hormone form of the insulin-like growth factor II has been confirmed to be the primary mechanism of hypoglycemia according to a study[4]. Han et al[5] reported that SFTs with Doege-Potter syndrome were often malignant. Our case showed typical features of Doege-Potter syndrome at the onset of disease and also the malignant features. However, these symptoms were non-specific.

Radiologically, homogeneous enhancement of the lesion in the arterial phase to portal venous phase on CT as well as low T1 signal intensity and high T2 signal intensity on magnetic resonance imaging can be observed in most of the cases[2]. The non-typical feature makes it difficult to distinguish SFTs from the other soft tissue tumors[6]. Particularly, it was reported that a malignant and larger tumor may present with hemorrhage, calcifications, cystic areas and so on[2]. A non-uniform enhancement was observed in the image examinations of our case that showed similar features.

Furthermore, although a higher FDG uptake on 18F-FDG PET/CT may be a sign of a malignant SFT, the diagnostic utility is still debatable due to its imperfect sensitivity[7]. However, in our case, the 18F-FDG PET/CT was useful in the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant SFTs and evaluation of clinical significance. Thus, 18F-FDG PET/CT examination is still a recommendation for the full evaluation of suspicious malignant tumors.

Recently, the NAB2-STAT6 fusion gene was found to express a unique molecular feature in 100% of SFT cases[8]. Thus, compared with other conventional IHC markers like CD34, STAT6 has been proved to be more sensitive (98%) and specific (85%) for SFT. Furthermore, a previous study reported that a higher risk of SFT aggressive behavior may be associated with specific NAB2-STAT6 fusion variants[9], which could be a biomarker for identifying the distinct molecular feature of malignant SFTs.

For pathologic features, grossly, the pancreatic SFTs range from 2.0-18.5 cm in diameter[10,11]. Tumors are usually well-circumscribed with a fibrous pseudocapsule. The cut surface may show a wide range of patterns from firm, white to tan, and fleshy mass with hemorrhage, necrosis, or calcification usually presented in large or malignant cases[2]. Histologically, a typical “patternless pattern”, i.e., various atypical spindled cells arrayed randomly within the stroma, can be seen in most cases (Table 2). People have defined malignant SFTs based upon its special histologic features: ≥ 4 mitotic figures per 10 HPFs, necrosis or hemorrhage, increased cellularity, nuclear pleomorphism, and a large size (> 10 cm). The histological results of our case meet these criteria and show high-grade malignant manifestations. However, a poor correlation with patients outcomes[12] has been seen as low validity in predicting the biological features of SFTs. Therefore, pathologists treat SFT as a neoplasm of intermediate biological potential. Furthermore, complete surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment for pancreatic SFTs and good results were reported (Table 2). Unfortunately, almost no information has been provided concerning systemic treatments for malignant pancreatic SFTs. For this reason, a multidisciplinary discussion, especially with the participation of pathologists, is recommended before initiation of treatment procedures for patients with an advanced stage of the disease.

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical and histological features along with outcomes of pancreatic solitary fibrous tumors

| Ref. | Immuno-histochemistry (+) | Histology | Risk assessment | Treatment | Follow-up |

| Lüttges et al[13] | CD34, CD99, Bcl-2, vimentin | No necrosis or mitoses | Benign | Distal pancreatectomy | Alive and well (20 mo) |

| Chatti et al[14] | CD34, CD99, Bcl-2, vimentin | “Regular spindle cells” | Benign | Enucleation | Died 3 d postoperatively due to complications |

| Gardini et al[15] | CD34, CD99, Bcl-2, vimentin, smooth muscle actin (focal) | NA | Benign | Traverso-longmire | Alive and well (16 mo) |

| Miyamoto et al[10] | CD34, Bcl-2 | No necrosis or mitoses | Benign | Laparoscopic enucleation | Alive and well (7 mo) |

| Kwon et al[16] | CD34, CD99, vimentin | “Typical bland spindle cells” | Benign | Median segmentectomy | NA |

| Srinivasan et al[17] | CD34, Bcl-2 | < 1 mitoses/10 HPFs, no necrosis | Benign | Distal pancreatectomy | Alive and well (7 mo) |

| Chetty et al[18] | CD34, CD99, Bcl-2 | No necrosis or mitoses | Benign | Whipple | Alive and well (6 mo) |

| Ishiwatari et al[19] | CD34, Bcl-2 | Necrosis, no mitoses | Benign | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | Alive and well (42 mo) |

| Sugawara et al[20] | CD34 | No necrosis or mitoses | Benign | Pancreaticoduoden-ectomy | NA |

| Azadi et al[6] | CD34, Bcl-2, Ki67 < 5% | No malignant features | Benign | Distal pancreatectomy | NA |

| Santos et al[21] | CD34, beta-catenin | No necrosis or mitoses | Benign | Partial pancreatectomy | NA |

| Tasdemir et al[11] | CD34, Bcl-2, beta-catenin, vimentin, Ki67 < 2% | 1-2 mitoses/10 HPFs | Benign | Enucleation | Alive and well (3 mo) |

| van der Vorst et al[22] | CD34, CD99, Bcl-2 | No necrosis or mitoses | Benign | Enucleation | NA |

| Chen et al[23] | CD34, Bcl-2, vimentin, CD68, muscle-specific actin | Necrosis, no mitoses | Benign | Whipple | Alive and well (30 mo) |

| Hwang et al[24] | CD34, Bcl-2, muscle-specific actin, CD10, ER, PR | “Spindle shaped cell with patternless cell deposition” | Benign | Duodenal preserving partial pancreatic head resection | Alive and well (30 mo) |

| Baxter et al[25] | CD34, Bcl-2 | NA | Benign | Whipple | NA |

| Estrella et al[3] | CD34, Bcl-2, keratin (rare), p16, p53 | Nuclear atypia, 17 mitoses/10 HPFs, necrosis | Malignant | Pancreaticoduoden-ectomy | Alive and well (40 mo) |

| Han et al[26] | CD34, CD99 | No necrosis or mitoses | Benign | Ultrasonography-guided needle biopsy | No metastasis or changes in the size after 10 mo |

| Murakami et al[27] | CD34, Bcl-2, STAT6, ACTH (focal), POMC (focal), NSE (focal) | “Spindle neoplastic cells in fascicular arrangement” | Benign | Distal pancreatectomy | Died 4 mo postoperatively due to sepsis |

| Paramythiotis et al[28] | CD34, CD99, Bcl-2, vimentin, S100 (focal) | No mitoses | Benign | Distal pancreatectomy | Alive and well (40 mo) |

| Spasevska et al[29] | CD34, vimentin, CD99, Bcl-2 (focal), nuclear beta-catenin (focal) | No necrosis or mitoses | Benign | Whipple | Died 1 wk postoperatively due to complications |

| Oana et al[30] | CD34, Bcl-2 | No necrosis or mitoses | Benign | Partial pancreatectomy | Alive and well (36 mo) |

| Current case | CD34, Bcl-2, STAT6, CD31, PHH-3, D2-40 and Ki67 > 10% | Necrosis, 4-5 mitoses/10 HPFs | Malignant | Distal pancreatectomy and hepatic tumor resection | Alive and well (6 mo) |

NA: Not applicable.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we present a malignant pancreatic SFT with systemic metastasis and typical Doege-Potter syndrome features. The diagnosis and prognosis evaluation of malignant SFTs rely on more accurate criteria combined with clinical, IHC, and histological evidence. Furthermore, prospective studies are needed to provide greater evidence about the systemic management of malignant pancreatic SFTs.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: December 5, 2019

First decision: December 11, 2019

Article in press: December 22, 2019

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Coskun A S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Hao Geng, Department of General Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Yu Ye, Department of General Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Yun Jin, Department of General Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Bai-Zhou Li, Department of Pathology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Yuan-Quan Yu, Department of General Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Yang-Yang Feng, Department of General Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Jiang-Tao Li, Department of General Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China. zrljt@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Klemperer P, Coleman BR. Primary neoplasms of the pleura. A report of five cases. Am J Ind Med. 1992;22:1–31. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700220103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang SC, Huang HY. Solitary fibrous tumor: An evolving and unifying entity with unsettled issues. Histol Histopathol. 2019;34:313–334. doi: 10.14670/HH-18-064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estrella JS, Wang H, Bhosale PR, Evans HL, Abraham SC. Malignant Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Pancreas. Pancreas. 2015;44:988–994. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fung EC, Crook MA. Doege-Potter syndrome and 'big-IGF2': a rare cause of hypoglycaemia. Ann Clin Biochem. 2011;48:95–96. doi: 10.1258/acb.2011.011020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han G, Zhang Z, Shen X, Wang K, Zhao Y, He J, Gao Y, Shan X, Xin G, Li C, Liu X. Doege-Potter syndrome: A review of the literature including a new case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7417. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azadi J, Subhawong A, Durand DJ. F-18 FDG PET/CT and Tc-99m sulfur colloid SPECT imaging in the diagnosis and treatment of a case of dual solitary fibrous tumors of the retroperitoneum and pancreas. J Radiol Case Rep. 2012;6:32–37. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v6i3.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tazeler Z, Tan G, Aslan A, Tan S. The utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT in solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2016;35:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.remn.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schweizer L, Koelsche C, Sahm F, Piro RM, Capper D, Reuss DE, Pusch S, Habel A, Meyer J, Göck T, Jones DT, Mawrin C, Schittenhelm J, Becker A, Heim S, Simon M, Herold-Mende C, Mechtersheimer G, Paulus W, König R, Wiestler OD, Pfister SM, von Deimling A. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma and solitary fibrous tumors carry the NAB2-STAT6 fusion and can be diagnosed by nuclear expression of STAT6 protein. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:651–658. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barthelmeß S, Geddert H, Boltze C, Moskalev EA, Bieg M, Sirbu H, Brors B, Wiemann S, Hartmann A, Agaimy A, Haller F. Solitary fibrous tumors/hemangiopericytomas with different variants of the NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion are characterized by specific histomorphology and distinct clinicopathological features. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:1209–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyamoto H, Molena DA, Schoeniger LO, Haodong Xu. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas: a case report. Int J Surg Pathol. 2007;15:311–314. doi: 10.1177/1066896907302419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tasdemir A, Soyuer I, Yurci A, Karahanli I, Akyildiz H. A huge solitary fibrous tumor localized in the pancreas: a young women. JOP. 2012;13:304–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C, Ferrone CR, Hussain M, Lewis JJ, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Clinicopathologic correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer. 2002;94:1057–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lüttges J, Mentzel T, Hübner G, Klöppel G. Solitary fibrous tumour of the pancreas: a new member of the small group of mesenchymal pancreatic tumours. Virchows Arch. 1999;435:37–42. doi: 10.1007/s004280050392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatti K, Nouira K, Ben Reguigua M, Bedioui H, Oueslati S, Laabidi B, Alaya M, Ben Abdallah N. [Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas. A case report] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:317–319. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardini A, Dubini A, Saragoni L, Padovani F, Garcea D. [Benign solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas: a rare location of extra-pleural fibrous tumor. Single case report and review of the literature] Pathologica. 2007;99:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon HJ, Byun JH, Kang J, Park SH, Lee MG. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas: imaging findings. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9 Suppl:S48–S51. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2008.9.s.s48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srinivasan VD, Wayne JD, Rao MS, Zynger DL. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas: case report with cytologic and surgical pathology correlation and review of the literature. JOP. 2008;9:526–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chetty R, Jain R, Serra S. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2009;13:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishiwatari H, Hayashi T, Yoshida M, Kuroiwa G, Sato Y, Kobune M, Takimoto R, Kimura Y, Hasegawa T, Hirata K, Kato J. [A case of solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas] Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2009;106:1078–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugawara Y, Sakai S, Aono S, Takahashi T, Inoue T, Ohta K, Tanada M, Teramoto N. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas. Jpn J Radiol. 2010;28:479–482. doi: 10.1007/s11604-010-0453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos LA, Santos VM, Oliveira OC, De Marco M. Solitary fibrous tumour of the pancreas: a case report. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2012;35:133–136. doi: 10.4321/s1137-66272012000100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Vorst JR, Vahrmeijer AL, Hutteman M, Bosse T, Smit VT, van de Velde CJ, Frangioni JV, Bonsing BA. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of a solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas using methylene blue. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;4:180–184. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i7.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen JW, Lü T, Liu HB, Tong SX, Ai ZL, Suo T, Ji Y. A solitary fibrous tumor in the pancreas. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:1388–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang JD, Kim JW, Chang JC. Imaging Findings of a Solitary Fibrous Tumor in Pancreas: A Case Report. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2014:70. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baxter AR, Newman E, Hajdu CH. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas. J Surg Case Rep. 2015:2015. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjv144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han SH, Baek YH, Han S-y, Lee SW, Jeong JS, Cho JH, Kwon H-J. Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Pancreas: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Korean J Intern Med. 2015:88. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murakami K, Nakamura Y, Felizola SJ, Morimoto R, Satoh F, Takanami K, Katakami H, Hirota S, Takeda Y, Meguro-Horike M, Horike S, Unno M, Sasano H. Pancreatic solitary fibrous tumor causing ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;436:268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paramythiotis D, Kofina K, Bangeas P, Tsiompanou F, Karayannopoulou G, Basdanis G. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas: Case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:461–466. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i6.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spasevska L, Janevska V, Janevski V, Noveska B, Zhivadinovik J. Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Pancreas: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki) 2016;37:115–120. doi: 10.1515/prilozi-2016-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oana S, Matsuda N, Sibata S, Ishida K, Sugai T, Matsumoto T. A case of a "wandering" mobile solitary fibrous tumor occurring in the pancreas. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017;10:535–540. doi: 10.1007/s12328-017-0774-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]