Interferons (IFNs) induce the expression of a number of antiviral genes that protect the cells of vertebrates against viruses and other microbes. The susceptibility of cells to viruses greatly depends on the level and activity of these antiviral effectors but also on the ability of viruses to counteract this antiviral response. Here, we found that the level of one of the main IFN effectors in the cell, the dsRNA-activated protein kinase (PKR), greatly determines the permissiveness of cells to alphaviruses that lack mechanisms to counteract its activation. These naive viruses also showed a hypersensitivity to IFN, suggesting that acquisition of IFN resistance (even partial) has probably been involved in expanding the host range of alphaviruses in the past. Interestingly, some of these naive viruses showed a marked oncotropism for some tumor cell lines derived from human hepatocarcinoma (HCC), opening the possibility of their use in oncolytic therapy to treat human tumors.

KEYWORDS: PKR, RNA structure, arbovirus, interferons, oncolytic viruses, translation

ABSTRACT

Alphaviruses are insect-borne viruses that alternate between replication in mosquitoes and vertebrate species. Adaptation of some alphaviruses to vertebrate hosts has involved the acquisition of an RNA structure (downstream loop [DLP]) in viral subgenomic mRNAs that confers translational resistance to protein kinase (PKR)-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation. Here, we found that, in addition to promoting eIF2-independent translation of viral subgenomic mRNAs, presence of the DLP structure also increased the resistance of alphavirus to type I interferon (IFN). Aura virus (AURAV), an ecologically isolated relative of Sindbis virus (SV) that is poorly adapted to replication in vertebrate cells, displayed a nonfunctional DLP structure and dramatic sensitivity to type I IFN. Our data suggest that an increased resistance to IFN emerged during translational adaptation of alphavirus mRNA to vertebrate hosts, reinforcing the role that double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-activated protein kinase (PKR) plays as both a constitutive and IFN-induced antiviral effector. Interestingly, a mutant SV lacking the DLP structure (SV-ΔDLP) and AURAV both showed a marked oncotropism for certain tumor cell lines that have defects in PKR expression and/or activation. AURAV selectively replicated in and killed some cell lines derived from human hepatocarcinoma (HCC) that lacked PKR response to infection or poly(I·C) transfection. The oncolytic activities of SV-ΔDLP and AURAV were also confirmed using tumor xenografts in mice, showing tumor regression activities comparable to wild-type SV. Our data show that translation of alphavirus subgenomic mRNAs plays a central role in IFN susceptibility and cell tropism, suggesting an unanticipated oncolytic potential that some naive arboviruses may have in virotherapy.

IMPORTANCE Interferons (IFNs) induce the expression of a number of antiviral genes that protect the cells of vertebrates against viruses and other microbes. The susceptibility of cells to viruses greatly depends on the level and activity of these antiviral effectors but also on the ability of viruses to counteract this antiviral response. Here, we found that the level of one of the main IFN effectors in the cell, the dsRNA-activated protein kinase (PKR), greatly determines the permissiveness of cells to alphaviruses that lack mechanisms to counteract its activation. These naive viruses also showed a hypersensitivity to IFN, suggesting that acquisition of IFN resistance (even partial) has probably been involved in expanding the host range of alphaviruses in the past. Interestingly, some of these naive viruses showed a marked oncotropism for some tumor cell lines derived from human hepatocarcinoma (HCC), opening the possibility of their use in oncolytic therapy to treat human tumors.

INTRODUCTION

The innate response of vertebrates against viruses requires cytosolic and membrane-bound sensors and mediators such as interferons (IFNs) that induce the antiviral state in bystander cells. Type I IFN induces the expression of a battery of genes (collectively known as interferon-stimulated genes [ISGs]) in target cells, which are directly involved in blocking viral replication at different steps (effectors) or in sensing viral infection (sensors) (1, 2). For all RNA and some DNA viruses, this antiviral pathway is initiated by activation of RNA sensors, such as RIG-I, MDA-5, and protein kinase (PKR), which collectively detect viral RNA species and trigger the synthesis of IFNs (mainly type I) through the activation of IRF3, IRF7, and NF-κB transcription factors (1, 3). The double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-activated protein kinase (PKR) (also known as EIF2AK2) acts not only as a viral RNA sensor but also as a potent antiviral effector, blocking translation by phosphorylating the alpha subunit of initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) in response to dsRNA accumulation (4, 5). The importance of PKR as an antiviral effector in vertebrates has been confirmed by the fact that virtually all virus families have developed a mechanism to block or counteract PKR activation in infected cells. Removal of these PKR antagonists results in highly attenuated mutants that also induce higher levels of IFN-α/β in infected cells, reinforcing the role of PKR as both an effector and inducer of IFN (6, 7). More recently, a synergistic link between PKR and some other RNA sensors, such as MDA-5, in type I IFN induction has been established (8).

Alphaviruses alternate between replication in insects (vectors) and vertebrate hosts, including rodents, horses, humans, and nonhuman primates. Semliki Forest virus (SFV) and Sindbis virus (SV) are widely distributed in the old world and are the prototypes of this genus (9). Based on genetic and phylogenic analysis, we recently proposed that adaptation of some alphaviruses to vertebrate hosts involved the acquisition of a stable RNA structure located 28 to 32 nucleotides (nt) downstream of the translation initiation codon in subgenomic (26S) mRNAs (10). This structure, termed the downstream loop (DLP), can promote eIF2-independent translation of viral mRNAs and resistance to PKR in SFV- and SV-infected cells (11, 12). As a result of eIF2α phosphorylation, stress granules (SGs) have been reported to be assembled early in alphavirus infection, disappearing later in the infection (13, 14). SG disassembly correlated with the recruitment of some SG components (G3BP or FXR) to viral factories through interactions with viral nonstructural protein 3 (nsp3) (15). Moreover, it has also been reported that efficient translation of SFV subgenomic mRNAs contributes to SG disassembly (13). Removing the DLP structure from the SV genome resulted in a mutant virus that replicated at low levels in normal murine fibroblasts (MEFs) and showed a high degree of attenuation in mice (10). DLP function not only relies on its stability to stall the scanning of preinitiation ribosomal complex (43-PIC) but also on a proper distance to the AUGi that allows for correct placement of 43S-PIC complex on the initiation codon of mRNA (16). We have recently found that Aura virus (AURAV), an SV-related virus isolated from mosquitoes in Central America, showed a suboptimal DLP structure that was unable to support the eIF2-independent translation that confers resistance to PKR activation (10). However, little is known about AURAV ecology and biology and whether it can infect vertebrate hosts in nature (17, 18).

Some viruses show an increased oncoselectivity, including naturally occurring nonpathogenic viruses and genetically manipulated pathogens lacking anti-PKR genes (e.g., vaccinia ΔE3 and herpes simplex virus [HSV] ΔICP34.5), and some have been used as oncolytic tools for the treatment of solid tumors (virotherapy) (19). The loss of PKR responses found in many tumor cell lines allows for selective replication of these viruses. Lower PKR activity has been detected in some hematological tumors, mainly in lymphoblastic leukemia, due to chromosomal rearrangements, aberrant splicing, or point mutations (20 – 22). In addition, the presence of a yet unidentified inhibitor of PKR has been proposed in tumors with oncogenic activation of the Ras/MEK pathway and in some lymphoblastic leukemia (23, 24). Moreover, since cell transformation is often linked to the loss of IFN response, tumor cells usually provide an optimal environment for the replication of viruses, especially those that are highly sensitive to IFN (19). More recently, some alphaviruses such as SV, SFV, and Getah-like M1 viruses have been used to kill tumor cell lines and tumor xenografts in mouse models, showing the potential for arboviruses in virotherapy (25 – 29). Here, we have studied in-depth the connections between translation control of alphavirus mRNAs, innate immune response, and oncotropism in naturally occurring and engineered viruses lacking anti-PKR mechanisms.

RESULTS

Translation of AURAV and SV-ΔDLP 26S mRNA is blocked in mammalian cells.

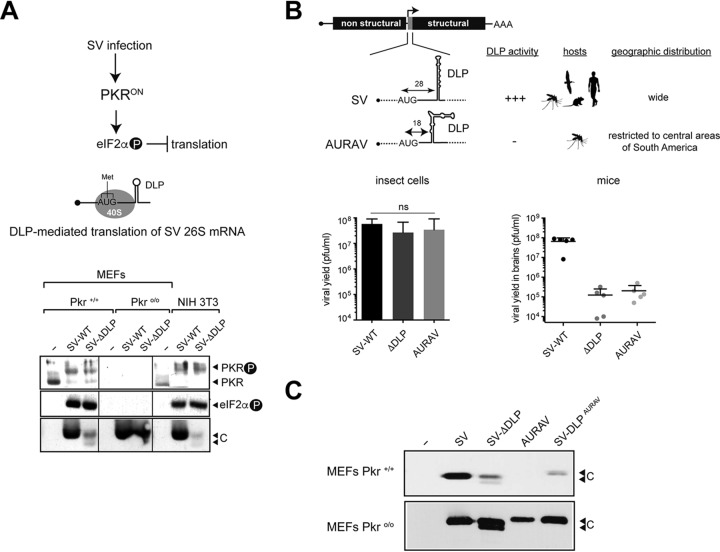

Removal of the DLP structure from the SV 26S mRNA generates a mutant virus (SV-ΔDLP) that is unable to overcome the PKR activation that occurs early upon SV and SFV infection of cultured fibroblasts (Fig. 1A) and in the brain of mice (10). Similar to SV-ΔDLP, AURAV was able to replicate at levels comparable to the SV wild type (WT) in mosquito cells but not in mice or in cultured fibroblasts (Fig. 1B and C), showing that this virus is not well adapted to vertebrates. To test whether this restriction results from the suboptimal DLP structure in AURAV subgenomic 26S mRNA, we replaced the DLP structure in SV with the equivalent region found in the AURAV genome. The resulting virus (SV-DLPAURAV) showed a restriction similar to that observed for SV-ΔDLP in wild-type MEFs but not in PKRo/o cells, reinforcing the notion that the absence of a functional DLP structure in the 26S mRNA restricted replication of AURAV in normal vertebrate cells (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

The DLP structure promotes PKR resistance and eIF2-independent translation of alphavirus mRNAs. (A) Diagram depicting the response/counter-response system that controls translation of alphavirus mRNAs in vertebrate cells. A representative Western blot showing mobility shift of the PKR band as a result of activation, eIF2 phosphorylation, and viral 26S mRNA translation (capsid protein [C]) in wild-type and Pkro/o MEFs. Vertical thin lines among samples indicate that the order of samples was changed from the original blot. (B) Schematic representation comparing DLP structures, host range, and geographic distribution of SV and AURAV. Quantification of viral yields in cultured insect cells (left) or in mice brain (right) after inoculation of SV-WT, SV-ΔDLP, and AURAV. No significant differences in viral yields were found in insect cells (ns). Note that the suboptimal DLP structure of AURAV mRNA does not promote eIF2-independent translation and viral replication, either in cultured vertebrate cells or in mice (10, 16). (C) Replacement of the SV DLP with its AURAV homolog generated a chimeric virus (SV-DLPAURAV) that became sensitive to PKR. A representative anti-SV capsid (C) Western blot from wild-type (Pkr+/+) or knockout (Pkro/o) cells infected with the indicated viruses is shown.

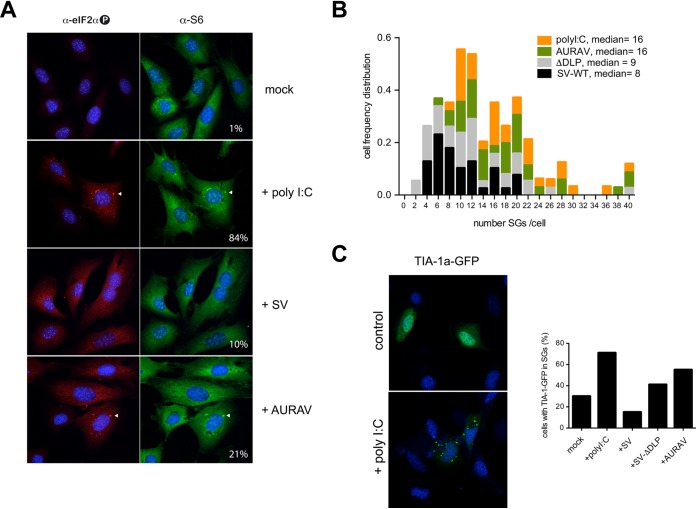

To compare SG dynamics in SV-WT-, SV-ΔDLP-, and AURAV-infected cells, we first scored the percentage of cells showing SGs and the number of SGs per cell using RPS6 as the SG marker. In agreement with previous reports, only 10% of cells infected with SV-WT showed SGs at 6 hours postinfection (hpi), whereas transfection with poly(I·C) resulted in 84% of cells showing SGs (Fig. 2A). Infection with AURAV increased the number of cells with SGs to 21%, a percentage similar to that observed in SV-ΔDLP-infected cells (data not shown). Moreover, the number of SGs per cell increased in AURAV-infected cells, reaching the median observed in cells transfected with poly(I·C) (Fig. 2B). To better compare SG disassembly activities of these viruses, we first transfected MEFs with a plasmid expressing the TIA-1a protein fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). Since TIA-1 is directly involved in SG assembly (30), ectopic accumulation of TIA1-EGFP in cells induced the spontaneous formation of SGs in ≈30% of cells, a percentage that increased to 70% after poly(I·C) transfection (Fig. 2C). Infection with SV-WT resulted in 15% of cells having SGs, whereas in cells infected with ΔDLP and AURAV, the percentages of SG-positive cells were 41% and 55%, respectively. Taken together, these results show that differential translation of subgenomic mRNAs in these viruses correlated with altered SG dynamics in infected cells.

FIG 2.

Stress granule dynamics in alphavirus-infected cells. (A) Comparative analysis of stress granules (SGs) assembled in cells infected with the indicated viruses at 6 hpi. Representative IF stained with anti-phospho-eIF2α (red) and RPS6 (green) showing the presence of SGs in AURAV-infected cells but considerably fewer in SV-WT-infected cells. As a positive control, cells were transfected with poly(I·C) for 6 h; the percentage of cells showing SGs is shown. Representative SGs are marked with white arrowheads. (B) Distribution of the number of SGs per cell after infection with the indicated virus at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell or transfection with poly(I·C). SGs were visualized after staining with anti-eIF3G antibody. (C) Effect of virus infection or poly(I·C) transfection on TIA-1a incorporation into SGs. HeLa cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing a TIA-1a-GFP fusion protein, and after 24 h, cells were infected with the indicated viruses or transfected with poly(I·C) and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy 6 h later. The percentage of cells showing TIA-1a-EGFP within SGs is represented as the mean of two independent experiments.

Downregulation of PKR activity promotes replication of AURAV.

To confirm the role of PKR in restricting AURAV replication in a controlled way, we used an MEF cell line that inducibly expresses vaccinia E3 protein (vE3) upon tetracycline (tet) withdrawal (10). vE3 is a well characterized inhibitor that prevents PKR activation both by direct interaction or by sequestering the dsRNA activator of the kinase (6, 31). In addition, vE3 partially inhibits type I IFN secretion by blocking the activation of IRF3/7 and NF-κB factors (32). Tet withdrawal induced the accumulation of vE3, thus making these cells resistant to poly(I·C)-induced cell death (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the presence of vE3 reduced the secretion of type I IFN up to 3-fold in response to poly(I·C) transfection, in good agreement with previous reports showing that PKR was required for maximal type I IFN secretion in response to poly(I·C) (4, 8, 33). However, induction of the antiviral state by IFN was not significantly affected by the presence of vE3 (Fig. 3A), suggesting that PKR activity was dispensable to mount a protective response against SV. Accumulation of vE3 dramatically increased the susceptibility of cells to AURAV infection, resulting in a 2 to 3 log10 increase in viral yields (Fig. 3B). As expected, replication of SV-WT was not affected by the presence of vE3. eIF2α phosphorylation and host translation shutoff were observed in uninduced MEFs infected with AURAV, with translation of viral 26S mRNA completely blocked in this situation. Accumulation of vE3 correlated with AURAV replication and prevented eIF2α phosphorylation in infected cells (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

An inducible model for AURAV replication in MEFs based on PKR inhibition. (A) Characterization of a MEF line that inducibly expresses the vaccinia E3 (vE3) protein (top), showing its effect on poly(I·C)-mediated cell killing (middle left) and type I IFN secretion (middle right). However, the antiviral state induced by IFN was not affected by vE3 expression (bottom). A recombinant SV expressing a luciferase mRNA bearing a DLP structure (16) was used to monitor virus replication (bottom). (B) vE3 accumulation upon tet withdrawal enabled replication of AURAV in MEFs. Viral yields are from cells infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 0.1 PFU/cell. The data are the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments; note that SV-WT yields were unaffected by vE3 expression. (C) Metabolic labeling of cells infected with the indicated viruses (MOI of 10 PFU/cell) at 6 h postinfection (hpi) (top). Western blot of vE3 accumulation and eIF2 phosphorylation in cells infected with AURAV at 6 and 8 hpi (bottom).

AURAV is hypersensitive to type I IFN.

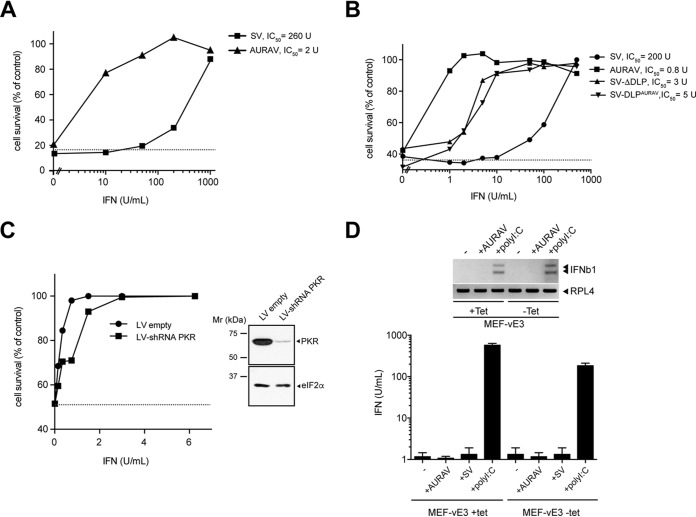

Since PKR also exerts its antiviral role through IFN, we next tested the sensitivity of AURAV to IFN. Sensitivity to IFN varies among viral families and greatly depends on the degree of adaptation of a given virus to a particular host (34, 35). Alphaviruses show a sensitivity to type I IFN similar to other RNA virus families, and a critical role of type I IFN in controlling the acute phase of alphavirus disease in animals has been well documented (36). To compare the sensitivity of AURAV and SV to type I IFN, Huh7 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of IFN-α/β and then challenged with these viruses. The Huh7 cell line was chosen because it shows moderate sensitivity to IFN and full permissiveness to AURAV (see below). AURAV showed a dramatic sensitivity to IFN-α/β, as 2 to 5 U/ml IFN-α/β was enough to fully protect the monolayer from AURAV-induced cell killing, which was a 100- to 200-fold lower concentration than that required to protect monolayers against SV-induced cell killing (Fig. 4A). We next evaluated the role of the DLP structure in conferring resistance to IFN-α/β. Notably, SV-ΔDLP and SV-DLPAURAV viruses were 50- to 100-fold more sensitive to IFN-α/β than the parental SV-WT, although none of them reached the sensitivity shown by AURAV (Fig. 4B). This result demonstrated that the presence of a functional DLP structure makes the virus more resistant to type I IFN. To test the contribution of PKR to the sensitivity of AURAV to IFN, we repeated the experiments in Huh7 cells where PKR expression was silenced by short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (Fig. 4C). PKR knockdown only slightly reduced the sensitivity of AURAV to low doses of IFN, showing that the contribution of PKR to AURAV type I IFN hypersensitivity was only partial.

FIG 4.

AURAV shows hypersensitivity to type I IFN. (A) A representative IFN sensitivity assay of AURAV and SV. Huh7 cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of type I IFN and then challenged with the viruses at an MOI of 0.1 PFU/cell. IFN-induced cytoprotection of monolayers was estimated as described in Materials and Methods and expressed as a percentage of control (IFN-untreated sample). Note that for this experiment, about 80% of the cell monolayer was destroyed by infection in control samples (dashed line). Concentration of 50% inhibition (IC50) was estimated by titrating the infectious virus produced in every sample. (B) A functional DLP increases resistance of the resulting virus to IFN. IFN sensitivity assays of SV-WT, SV-ΔDLP, AURAV, and SV-DLPAURAV are shown. A representative experiment was carried out as described in panel A. Note that for this experiment, viruses killed 60% of cell monolayers in control samples (dashed line). (C) Silencing of PKR expression in Huh7.5 cells partially reduced the sensitivity of AURAV to low doses of type I IFN. The experiment was conducted as described in panel A, and data are expressed as the mean of two independent experiments. The level of PKR silencing in this experiment was confirmed by Western blotting against PKR (FJ6 antibody) in parallel wells (right). (D) Similar to SV, AURAV replication in cultured cells did not result in type I IFN secretion. Semiquantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of IFNb1 mRNA accumulation in response to AURAV infection (16 hpi) or transfection with poly(I·C) (16 hours posttransfection [hpt]) in MEFs expressing or not vE3. RPL4 represents a housekeeping mRNA analyzed in parallel (top). Type I IFN secretion in response to AURAV, SV, or transfection with poly(I·C) is also shown. After 14 h of treatment, the medium was collected, and IFN concentration was estimated as described in Materials and Methods (bottom). Data represent the mean of three independent experiments (± SD).

Since even very low levels of secreted IFN-α/β limited the replication of AURAV in MEFs, we measured both the accumulation of IFNb1 mRNA and secreted IFN-α/β in response to infection. Neither IFN-α/β secretion, nor IFNb1 gene induction were observed in cells infected with AURAV regardless of the presence of vE3 (Fig. 4D), showing that infection of cultured fibroblasts with AURAV did not result in detectable IFN-α/β secretion, which is the same as for other alphaviruses (29, 37, 38).

Replication of AURAV and SV-ΔDLP in tumor cell lines.

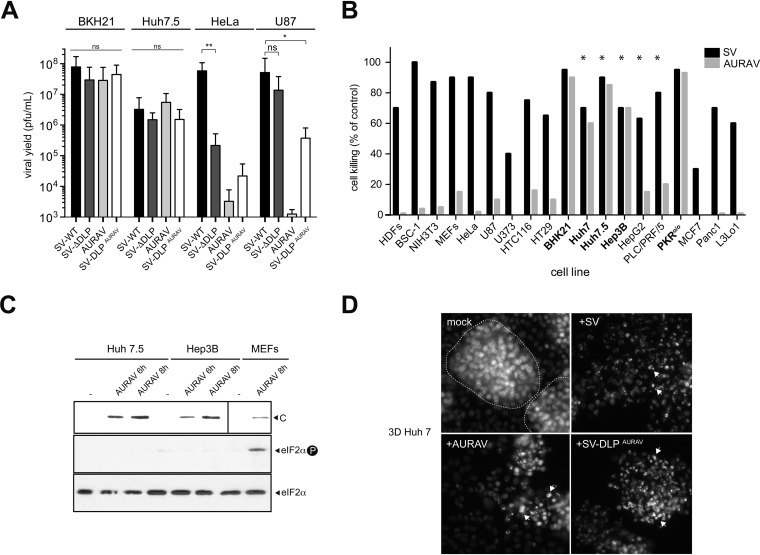

Since PKR expression and/or activation are altered in some lymphocytic, hepatic, and lung cancers as well as in many tumor cell lines, we wanted to test the replication of AURAV and SV-ΔDLP in a panel of common tumor cell lines. First, we tested the replication of these viruses in four cell lines of different origin (BHK21, HeLa, Huh7.5, and U87). Like previously reported, BHK21 cells showed a high degree of susceptibility to AURAV, SV-ΔDLP, and SV-WT (10), whereas in HeLa cells only SV-WT was able to replicate at high levels (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the hepatocarcinoma (HCC) Huh7.5 cell line was equally susceptible to all alphaviruses tested, whereas the glioblastoma U87 cell line allowed replication of SV-ΔDLP but not AURAV. The presence of the AURAV DLP in SV-DLPAURAV drastically reduced SV replication in HeLa cells and to a lesser extent in U87 cells, suggesting that the observed low susceptibility of these cells to AURAV mainly relies on a restricted translation of AURAV mRNA. However, our data clearly suggest that there are other factors apart from DLP functionality that also contribute to the lower permissivity of HeLa and U87 to AURAV infection (see below). We extended our study to other cell lines derived from hepatocellular (Hep3B, HepG2, PLC/PRF/5), colorectal (HTC116, HT29), pancreas (Panc1, L3Lo1), glioblastoma (U373), and breast (MCF7) cancers. Only some human HCC lines supported efficient replication of AURAV, whereas cell killing associated with SV replication was observed in almost all cell lines tested (Fig. 5B). Huh7 (and its derivative Huh7.5) and Hep3B showed the greatest susceptibility to AURAV, reaching viral yields and associated cell killing similar to SV-WT. Notably, no eIF2α phosphorylation was detected in Huh7.5 and Hep3B cells infected with AURAV (Fig. 5C), showing that PKR was not significantly activated in these cells in response to infection.

FIG 5.

Replication of AURAV in tumor cell lines. (A) Comparative analysis of virus replication in BHK21, Huh7.5, HeLa, and U87 cell lines. Viral yields were titrated 2 to 3 days after infection. Data represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. (B) Cell killing associated with replication of AURAV and SVs in different cell lines. In all cases, cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1 PFU/cell and analyzed 3 to 4 days later. Data are the mean of two independent experiments. Cell lines that promoted AURAV replication and cell killing are in bold. Those cell lines derived from hepatic tumors are marked with asterisks. (C) Analysis of viral capsid (C) accumulation (top) and eIF2 phosphorylation (middle) in HCC cell lines infected with AURAV. Cells were infected at a high MOI (25 PFU/cell) and analyzed at 6 and 8 h postinoculation. For comparison, an extract of MEFs infected with AURAV was included. To detect the AURAV capsid protein, a 3-fold more extract of infected MEFs was loaded in the gel (top right). (D) Cell killing associated with virus replication in 3D cultures of Huh7 cells. Huh7 cells were embedded in Matrigel for 6 days and then were infected with 105 PFU of the indicated virus, and the cultures were fixed and stained with DAPI 5 days later. Virus-induced spheroid breakage and nuclear condensation suggestive of cell death are marked with arrows. Dotted lines demarcate intact spheroids.

It has been reported before that Huh7 cells can form 3-dimensional (3D) spheroids resembling proto-bile canaliculi structures when growing in the presence of Matrigel (39). These structures resemble the organoids that have recently been derived from liver biopsies of patients with HCC (40), offering the possibility to test the replication capability of AURAV in these tumor-like structures generated in vitro. Infection of Huh7 3D cultures with SV and SV-DLPAURAV resulted in a rapid destruction of the spheroids due to a massive cell death associated with the infection (Fig. 5D). AURAV also destroyed the integrity of the spheroids, although following a more delayed kinetic, showing that AURAV can also infect and kill these tumor-like structures (Fig. 5D).

Replication of AURAV in HCC cell lines is associated with PKR downregulation.

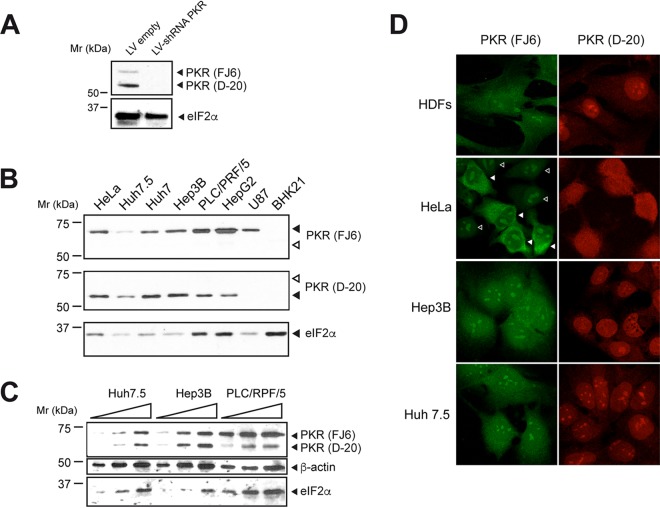

We next analyzed the expression and subcellular location of PKR in tumor cell lines that are susceptible or resistant to AURAV infection. In addition to the main 68-kDa band, other species of higher and lower molecular weight have been described for human PKR. Thus, a 52-kDa band accumulated in the nucleus in some T leukemia cell lines, although it is not clear whether this band represents a truncated form of the PKR protein or an isoform of PKR generated from an alternative mRNA (41). We used two different PKR antibodies that preferentially recognized the 68-kDa band (FJ6) and the 52-kDa band (D-20) of human cells as described previously (41). We confirmed that both isoforms corresponded with PKR since they disappeared when PKR expression was silenced by shRNA (Fig. 6A), although we found that the 52-kDa form was much more stable than the 68-kDa one. All cell lines analyzed except BHK21 expressed the 68-kDa band, although the level of expression varied somewhat (Fig. 6B). Among the hepatic cancer cell lines, the highly susceptible Huh7 and Hep3B expressed less 68-kDa band and more 52-kDa band, whereas cell lines PLC/PRF/5 and HepG2 (which were resistant to AURAV infection) showed the opposite (Fig. 6B and C). We also analyzed the subcellular location of both bands in some representative cell lines. The 68-kDa band showed cytoplasmic staining, whereas the 52-kDa one preferentially accumulated in the nucleus as reported before (Fig. 6D) (41).

FIG 6.

PKR expression, subcellular location, and activation in different cell lines. (A) Western blot analysis of Huh7.5 cells transduced with lentivirus (LV) expressing or not PKR shRNA, showing the disappearance of 65- and 55-kDa bands. The blot was probed with a mixture of FJ6 and D-20 antibodies. (B) Expression of PKR forms in the indicated cell lines analyzed by Western blotting with FJ6 and D-20 antibodies that preferentially detect the 68-kDa and 52-kDa forms, respectively. The blot was also probed with antibody against eIF2α. (C) A detailed comparison of PKR expression among HCC cell lines susceptible (Huh7.5 and Hep3B) and resistant (PLC/PRF/5) to AURAV infection is shown. Increasing amounts of cell extracts were probed with the indicated antibodies. The blot was also probed with antibodies against beta-actin and eIF2α. (D) Subcellular location of PKR forms analyzed by IF. Samples were incubated with FJ6 or D-20 antibodies and stained with Alexa 488 and Alexa 595 secondary antibodies, respectively. To confirm specificity of the FJ6 antibody, we used a mixture of HeLa cells expressing or not the PKR shRNA (empty and filled arrowheads, respectively).

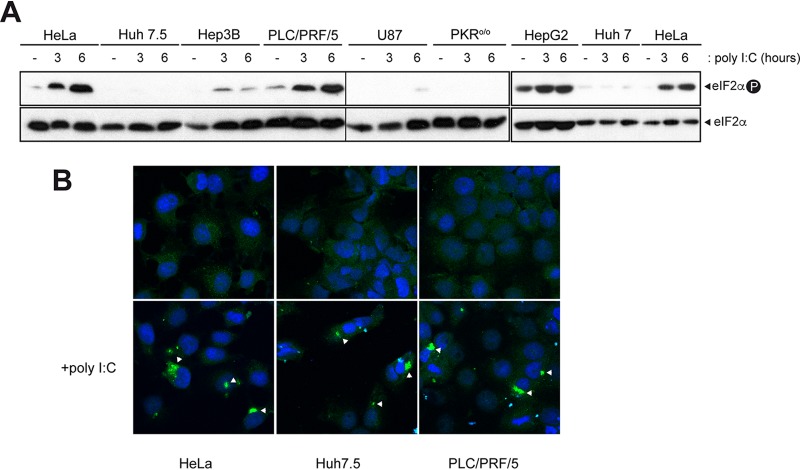

Next, we tested PKR activation in response to poly(I·C), a potent PKR activator that could be efficiently internalized within the cells using lipotransfectin as a facilitator (see Materials and Methods). As a readout of PKR activation, we measured the levels of phosphorylated eIF2α. Notably, we found an inverse correlation between poly(I·C)-mediated PKR activation and permissiveness to AURAV for most cell lines tested so that those cells susceptible to AURAV (Huh7, Huh7.5, and Hep3B) were unable to phosphorylate eIF2α in response to poly(I·C) transfection (Fig. 7A). On the contrary, cell lines resistant to AURAV (PLC/PRF/5 and HepG2) showed a robust eIF2α phosphorylation in response to PKR activator. PKR also became strongly activated in HeLa cells upon poly(I·C) transfection, explaining the restriction showed by this cell line to SV-ΔDLP replication (Fig. 7A and Fig. 5A). To rule out the possibility of inefficient internalization of poly(I·C) in those cells that did not activate PKR, cells were subjected to immunofluorescence (IF) analysis with the anti-dsRNA J2 antibody after transfection. Poly(I·C) accumulated to a similar level in all the cells tested, leading to cytoplasmic granules of considerable size that have been described previously (Fig. 7B) (42). These results showed that PKR was not efficiently activated, as measured by levels of phosphorylated eIF2α, in those cell lines permissive to AURAV.

FIG 7.

Cells susceptible to AURAV show defects in PKR activation. (A) Western blot of PKR-mediated eIF2 phosphorylation in cell lines transfected with poly(I·C). At the indicated times posttransfection, cell extracts were made and probed with anti-phospho and total eIF2α antibodies. Parallel transfections with EGFP-expressing plasmids showed similar transfection efficiency among cell lines. Samples from 1 to 12 and from 13 to 18 were analyzed in two separated gels that were blotted in parallel (denoted with a vertical thin line) and normalized using replicate samples 1 to 3. (B) IF micrographs of some representative cell lines probed with anti-dsRNA antibody (J2). The accumulation of dsRNA in cytoplasmic granules of poly(I·C)-transfected cells is shown (white arrowheads).

Since PKR expression increases upon type I IFN treatment, we primed Huh7.5 cells with a high dose of IFN-α/β to induce accumulation of PKR before testing its activation by poly(I·C) transfection. PKR levels strongly increased (>10-fold) in Huh7.5 cells treated with IFN-α/β, whereas parallel treatment of HeLa cells with an identical dose of IFN-α/β only slightly increased the accumulation of PKR, showing that HeLa cells constitutively express high levels of this kinase (Fig. 8A). IF analysis confirmed that the induced PKR accumulated in the cytoplasm of Huh7.5 cells as expected (Fig. 8B). eIF2α phosphorylation upon poly(I·C) transfection could be clearly detected in Huh7.5 + IFN-α/β after a long exposure of the gels, since Huh7.5 expressed lower basal levels of eIF2α than HeLa cells (Fig. 8A). However, the relative levels of eIF2α phosphorylation in Huh7.5 + IFN-α/β never reached those observed in HeLa cells. This supports the notion that both low levels and activation defects of PKR accounted for the reduced eIF2 phosphorylation in Huh7.5 cells in response to poly(I·C).

FIG 8.

Low PKR expression and activation defects in Huh7.5 cells. (A) Western blotting analysis of HeLa cells treated or not with 100 U/ml IFN-α/β and then transfected with 0.5 μg of poly(I·C) for the indicated times. Cell extracts were probed with anti-PKR (both FJ6 and D-20), anti-phospho-eIF2α, and anti-eIF2 antibodies. Two different exposures of the anti-phospho-eIF2α blot are shown. Quantification of phospho-eIF2α levels was normalized by the total eIF2α content in each sample, with values expressed in arbitrary units. (B) IF micrographs showing the accumulation of PKR (FJ6 antibody) in the cytoplasm of Huh7.5 cells pretreated with IFN.

Additional determinants apart from PKR are involved in susceptibility of vertebrate cells to AURAV infection.

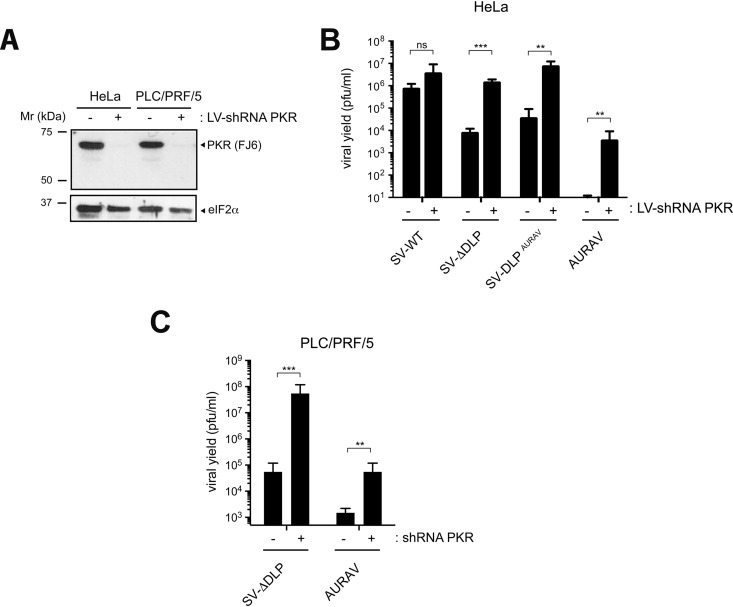

Since the lack of PKR activation observed in U87 cells fully recovered the replication of the SV-ΔDLP and SV-DLPAURAV viruses (Fig. 5A and 7A) but not that of AURAV, it seems that additional determinants apart from PKR downregulation influence cell susceptibility to AURAV infection. To confirm this idea, we silenced PKR expression in nonpermissive HeLa cells by means of transduction with lentiviral particles expressing an shRNA targeting human PKR mRNA (Fig. 9A). Knockdown of PKR expression enabled replication of SV-ΔDLP and SV-DLPAURAV to SV-WT levels, whereas replication of AURAV was only partially recovered (Fig. 9B). Similar results were obtained when we repeated the experiment in the PLC/PRF/5 cell line, which expresses high levels of activatable PKR (Fig. 9C) and, unlike the rest of the HCC cell lines, did not support AURAV replication. These results suggested the existence of additional determinants apart from PKR that can determine the tropism of AURAV.

FIG 9.

Additional determinants apart from PKR regulate permissiveness to AURAV infection. (A) Western blot showing levels of PKR silencing in HeLa and PLC/PRF/5 cell lines transduced with lentivirus (LV) expressing or not shRNA PKR. The blot was probed with FJ6 and anti-eIF2 antibodies. (B) Effect of PKR silencing on replication of the indicated viruses in HeLa cells. Cells were infected at an MOI of 1 PFU/cell, and viral yields were titrated 3 days later. Data are the mean ± SD of four independent experiments. (C) A similar experiment as described in panel B was carried out in PLC/PRF/5. Data are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Tumor regression activity.

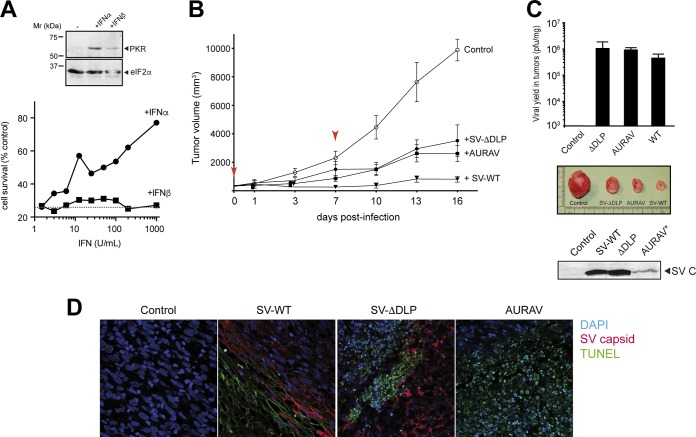

To better evaluate the oncolytic activity of AURAV and SV-ΔDLP, we induced tumor xenografts of BHK21 cells in SCID mice to test the tumor regression activity of these viruses. In this model, subcutaneously engrafted BHK21 cells generate fast-growing tumors that are visible after 1 week (25). Although the origin of BHK21 cells is embryonic rather than tumoral, they represent an example of a highly tumorigenic cell line with low PKR expression and activity (Fig. 10A). Moreover, we found that BHK21 cells weakly responded to type I IFN (Fig. 10A). Two intraperitoneal doses of SV-WT were enough to suppress tumor growth almost completely (Fig. 10B). Notably, inoculation of SV-ΔDLP and AURAV also blocked tumor growth, although in a slightly less efficient way than SV-WT (Fig. 10B). All three viruses replicated within the tumors (Fig. 10C), leading to comparable levels of intratumoral cell apoptosis (Fig. 10D). Finally, none of these viruses were detected in the main organs of the animals analyzed (liver, brain, and spleen) (data not shown), suggesting that viral replication was restricted to the tumor.

FIG 10.

Tumor regression activities of SV-WT, SV-ΔDLP, and AURAV. (A) PKR levels in BHK21 cells after type I IFN treatment analyzed by Western blotting using anti-PKR (D-20) and eIF2α antibodies (top). The bottom panel shows an IFN-mediated antiviral response assay against AURAV in BHK21 cells. The estimated IC50 for IFN-α was 200 U/ml, whereas IFN-β showed no effect on BHK21 cells. (B) Subcutaneous tumors of BHK21 cells were induced in SCID mice, and when indicated (red arrowheads), mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with two doses of 107 PFU of the indicated virus (n = 5 per group). Tumor size was measured every 3 days and plotted; bars show the 95% confidence interval (CI). At the end of the experiment, mice were sacrificed and tumors were extracted and split into two parts. (C) One part was used to prepare cell extracts for viral yield estimation (top) and to detect the presence of viral antigen by Western blot (bottom). A representative photograph of tumor size is shown (middle). (D) The other part of the tumor biopsies was fixed and subjected to TUNEL (green), coupled to IF with anti-SV capsid protein in order to detect infected cells (red). Note that regions expressing viral antigens also showed an intense TUNEL staining. Note that antibodies raised against SV capsid cross-react with AURAV capsid protein in Western blotting but not in IF.

DISCUSSION

Although the evolutionary history of Alphavirus is still a matter of debate, the existence of members that are poorly adapted to vertebrates such as AURAV and Eilat virus may be suggestive of an insect origin for this genus (10, 43, 44). The subsequent adaptation to vertebrates probably involved both changes in virus-host interaction and the acquisition of new functions to counteract or overcome the PKR response of vertebrate cells. Here, we found that the presence of a DLP structure in some alphaviral 26S mRNAs conferred not only eIF2-independent translation and PKR resistance, but it also decreased the sensitivity of those viruses to type I IFN. Our findings confirmed the central role of PKR as both a constitutive and IFN-mediated effector against alphaviruses, probably in combination with other ISGs. The increase in expression of PKR (and other ISGs) after type I IFN treatment probably would result in a stronger response against the virus, especially for those cells that express low basal levels of PKR (such as Huh7 cells), thus increasing the translational dependence of alphaviral subgenomic mRNAs on the DLP structure. Taken together, our results suggest that the acquisition of DLP structures in the subgenomic mRNA of some alphaviruses, such as SV and SFV, may have emerged as an integral solution to improve the synthesis of structural proteins in vertebrate cells while at the same time reducing sensitivity to type I IFN, which could have enabled expansion of their host range in the past. A poor adaptation by AURAV to vertebrates correlates well with its hypersensitivity to PKR and IFN, a finding that further supports our model of alphavirus adaptation to vertebrates through acquisition of the DLP.

The natural downregulation of PKR expression and activation in certain HCC cell lines allowed AURAV replication and oncolysis, a finding that opens the possibility to use this virus for virotherapy of HCC. Interestingly, a similar but not identical pattern of oncotropism has been reported for alphavirus Getah-like M1 (29). Both viruses efficiently replicated in a Hep3B cell line that showed a reduced IFN response and low basal expression of ISGs but not in PLC/PRF/5 cells that showed the opposite (29, 45). However, unlike AURAV, M1 virus has a functional DLP structure that conferred translational resistance to eIF2 phosphorylation in MEFs, indicating that the M1 virus is probably more adapted to vertebrates than AURAV (16). Thus, we conclude that the oncoselectivity of AURAV seems to be higher than the rest of the alphaviruses tested so far although more restricted to some HCC cell lines.

The low expression of the 65-kDa PKR form, together with an increased accumulation of the nuclear 55-kDa form in Huh7 and Hep3B cells, could explain the low level of eIF2 phosphorylation observed in these cell lines in response to poly(I·C) transfection or AURAV infection. The accumulation of the PKR 55-kDa form in the nucleus of Huh7 and Hep3B cells may be related to the nuclear functions of PKR previously reported in myeloid leukemia cells, which are clearly differentiated from PKR-mediated eIF2 phosphorylation in the cytoplasm (41). Nevertheless, in addition to differences in PKR expression and location, our data suggest that Huh7 cells also show an intrinsic defect in PKR activation since the accumulated PKR after IFN treatment only partially restored eIF2 phosphorylation in response to poly(I·C) in these cells. Perhaps the oncogenic signals and/or the pathways that are dysregulated in Huh7 and Hep3B cells could lead to the downregulation of PKR activity as described before for murine cells transformed with the Ras oncoprotein (24). Many proteins have been reported to interact with PKR, impacting the activity of the kinase in either a positive (e.g., PACT) or negative (e.g., NPM1) way, although the role of these proteins in regulating PKR activity in cancer cells is unknown (46). Another possibility is that the accessibility of PKR to activator dsRNA may be limited in some tumor cell lines by the presence of RNA binding proteins that sequester the dsRNA in a similar way to some viral PKR antagonists such as vE3.

Our data clearly showed that, apart from the presence of a functional PKR, other factors can determine the tropism of AURAV. As for most alphaviruses, the cellular receptor(s) used by AURAV to enter the cells has not yet been identified. However, the existence of naturally susceptible cells, such as BHK21 and certain HCC lines, undoubtedly showed that AURAV can use one or more receptors to enter vertebrate cells. Thus, only those cells that simultaneously express high levels of the putative AURAV receptor and low levels of PKR would be permissive to AURAV, a circumstance that probably occurs in the Huh7, Hep3B, and BHK21 cell lines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and animals.

Cell lines were grown under standard conditions at 37°C and 5% CO2, using Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum as growth medium except for NIH3T3 cells, where bovine serum was used instead. MEFs were derived from PKRo/o mice as described previously (11). Human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) were purchased from Lonza. The rest of the cells were purchased from ATCC and include the following: BHK21, HeLa, U87, U373, Hep3B, Huh7.5, PLC/PRF/5, HepG2, Jurkat, MCF7, Panc1, HCT116, and HT29. C6/36 mosquito cells were grown at 28°C as described previously (10). An MEF line coexpressing the vaccinia E3 protein and EGFP under the control of a tetracycline promoter (Tet-Off) was described previously (7). To improve homogeneity of expression, MEF-E3/GFP cells were induced by tet withdrawal for 5 days, and cells expressing the top 10% of EGFP were sorted and selected for further experiments. For 3D Matrigel-embedded cultures, 50 ml of complete medium containing 5 × 103 Huh7 cells was added to 50 ml of growth factor-reduced Matrigel with a protein concentration ranging from 7 to 7.5 mg/ml (BD Biosciences). After gently mixing, cells were deposited into either an 8-well chambered cover glass (Nalge Nunc International) or a 48-well plate, depending on the experiment, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were then covered with complete medium and grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 6 days, changing the medium every 2 days.

Three-month-old 129SvEv mice were inoculated intranasally with 107 PFU of each virus, and 3 days later virus yield in brain homogenates was estimated by plaque assay as described previously (7).

Viruses.

SV (Toto 1101 clone), AURAV (strain BeAR 10315), and SV lacking DLP structure (SV-ΔDLP) were grown in BHK21 cells, concentrated by polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG 6000) precipitation and purified on a sucrose cushion as described previously (11). Titration was carried out by standard plaque assay or by endpoint dilution assay. To exchange the DLP structure of SV for the AURAV DLP, we first constructed an SV cassette by inserting an SphI site within the AUGi and a NotI site at the end of the DLP structure in the SV cDNA clone. An overlap-extension PCR was performed on the pT7-SV clone using the following combinations of primers: SV_6863 (GGTACTGGAGACGGATATCGC) and SV_cassette_SphI (GGCAGTGGGGGCCGGGAAGGGGCGGCGGCCGAGCATGTAAAGAATCCTCTATGCATGCTGGTGGTGTTGTAGTATTAG) and SV_8101 (GATAGCACAGGGTGGTCGATGG) and SV_cassette_NotI (GGCCGCCGCCCCTTCCCGGCCCCCACTGCCATGTGGAGGCCGCGGAGAAGGAGGCAGGCGGCCCCGATGCGCGGCCGCAACGGGCTGGCTTCTC), and the resulting DNA fragment was cloned into the pT7-SV cDNA clone using HpaI and PmlI enzymes. The SV generated from this clone was indistinguishable from parental SV. To generate SV-DLPAURAV, we PCR amplified the AURAV DLP region using primer 5′ SphI_Aura (GCAGCATGCACTCTGTC TTTTACAATCCG) and 3′ AURADLP_NotI (CTTGGCCTGGCTTCGCGCTACGCAGCGGCCGCCTCTAACAGCCCTAGTGAGCTGTTGGATCTGGG). The resulting PCR fragment was cloned into the pT7-SV cassette using the SphI and NotI enzymes. Capped viral RNA was synthesized using the HiScribe T7 transcription system and vaccinia capping system (NEB), and 1.5 μg of the resulting RNA was electroporated into BHK21 cells to obtain viral progeny as described previously (11).

Cell-killing assays.

Virus-induced cell killing was estimated by the crystal violet staining method. Briefly, cells were fixed with 5% formaldehyde for 30 min and then stained with 0.5% crystal violet for another 30 min. Wells were washed extensively with distilled water, dried overnight, and solubilized in 10% acetic acid for 2 h. Finally, the resulting absorbance at 595 nm was measured in a 96-well microplate reader.

Metabolic labeling of proteins.

Cells growing in 24-well plates were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20 PFU/cell and labeled with 25 μCi/ml of [35S]methionine-cysteine at the indicated times for 30 min in medium lacking methionine. After washing with cold medium, monolayers were lysed in a sample buffer, boiled, and analyzed in a 12% SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography as described previously (11).

Western blotting and immunofluorescence.

Primary antibodies used in this work were anti-PKR antibodies (D-20, B10, and FJ6; Santa Cruz Biotech), anti-phospho51eIF2 (Invitrogen and Cell Signaling), anti-eIF2α (Santa Cruz Biotech), anti-TIA1 (Santa Cruz Biotech), anti-eIF3G (Saint John’s lab), and anti-SV C (12). Western blotting was carried out as described (11), revealing bands with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (GE) and quantifying them by densitometry. For immunofluorescence (IF) analysis, cells were grown on coverslips, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at room temperature (RT), treated with 50 mM NH4Cl, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 buffer, blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated with the indicated antibody for 2 h at RT. Coverslips were then washed and incubated with a secondary antibody coupled to Alexa 488 or 594 for 1 h at RT, washed, stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and mounted. Slides were examined and photographed on a multiphoton confocal microscope.

Poly(I·C) and plasmid transfection.

Transfections were carried out in 24-well plates using 2 μl of lipotransfectin (Niborlab) as a facilitator. Poly(I·C) (Sigma) was used at 0.1 to 1.5 μg/ml, and plasmids were used at 1 μg/ml. Transfection efficiency was greater than 70% in all cell lines tested.

IFN assays.

Type I IFN was titrated in MEFs or HeLa cells using an SV-expressing luciferase (SV-DLP-Luc) as a readout. To estimate IFN concentration, a standard of murine or human IFN-α/β (Prolab) was used. For IFN protection assays, cells grown in 24-well plates were primed with the indicated units of IFN for 16 h and then challenged with the viruses at an MOI of 0.1 PFU/cell.

Detection of IFNb1 expression by reverse transcriptase PCR.

To detect murine IFNb1 mRNA, total RNA was isolated from 6-well plates of MEFs using the RNeasy Plus minikit (Qiagen). After reverse transcription of 0.5 μg of total RNA using SuperScript III (Invitrogen) and random primer (hexamers), a semiquantitative PCR was carried out using the following pairs of primers: F_IFNb1_m (CCCTATGG AGATGACGGA) and R_IFNb1_m (CTGTCTGCTGGTGGAGTTC) and F_RPL4 (GTTTGACCAACCAAAACCTG) and R_RPL4 (TCTGGGCTTTTCAA GATTCTG). Amplification was limited to 20 cycles.

Tumor regression assay.

BHK21 tumors were induced by inoculating 106 cells subcutaneously in the hind flank of SCID mice (6-week-old females; Charles River). After a 1-week latency period, when palpable masses of about 400 mm3 were evident, the animals were inoculated intraperitoneally with 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 107 PFU of the indicated viruses. This inoculation was repeated 6 days later, and tumor volumes were measured every 3 days over a period no longer than 20 days, at which time the mice were euthanized according to ethical guidelines. Tumors of representative animals were recovered for histological analysis and for virus titration.

Apoptosis detection by TUNEL.

Tumors were surgically removed, fixed, embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm sections were prepared. Then, slides were deparaffinized, hydrated, and subjected to TUNEL using the in situ cell death detection kit (Roche). Samples were then subjected to IF as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Parametric (t test and analysis of variance [ANOVA]) and nonparametric (Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis) tests were performed in GraphPad Prism 6. P values higher than 0.05 were considered as nonsignificant (ns).

Ethics Statement.

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in Directive 86/609/EEC of the European Union on the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes, implemented by the Spanish Government under approval number 1201/2005. The protocol was approved by the committee on the ethics of animal experiments of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (permit number CEI 20-419). All surgery was performed under isoflurane anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Paloma Martín (IIB, Madrid), Esteban Domingo, and Jaime Millán (CBMSO) for providing us with HCC and hepatoma cell lines. We also thank Juan Valcárcel (CRG, Barcelona) for the pTIA-1a-EGFP plasmid and Bruno Hernández (CBMSO) for providing us with murine IFNs. The technical assistance of Laura Barbado is also acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pichlmair A, Reis e Sousa C. 2007. Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity 27:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadler AJ, Williams BR. 2008. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat Rev Immunol 8:559–568. doi: 10.1038/nri2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Habjan M, Pichlmair A. 2015. Cytoplasmic sensing of viral nucleic acids. Curr Opin Virol 11:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balachandran S, Roberts PC, Brown LE, Truong H, Pattnaik AK, Archer DR, Barber GN. 2000. Essential role for the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase PKR in innate immunity to viral infection. Immunity 13:129–141. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stojdl DF, Abraham N, Knowles S, Marius R, Brasey A, Lichty BD, Brown EG, Sonenberg N, Bell JC. 2000. The murine double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR is required for resistance to vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol 74:9580–9585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9580-9585.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia MA, Gil J, Ventoso I, Guerra S, Domingo E, Rivas C, Esteban M. 2006. Impact of protein kinase PKR in cell biology: from antiviral to antiproliferative action. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70:1032–1060. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00027-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domingo-Gil E, Toribio R, Najera JL, Esteban M, Ventoso I. 2011. Diversity in viral anti-PKR mechanisms: a remarkable case of evolutionary convergence. PLoS One 6:e16711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pham AM, Santa Maria FG, Lahiri T, Friedman E, Marie IJ, Levy DE. 2016. PKR transduces MDA5-dependent signals for type I IFN induction. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005489. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss JH, Strauss EG. 1994. The alphaviruses: gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol Rev 58:491–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ventoso I. 2012. Adaptive changes in alphavirus mRNA translation allowed colonization of vertebrate hosts. J Virol 86:9484–9494. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01114-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ventoso I, Sanz MA, Molina S, Berlanga JJ, Carrasco L, Esteban M. 2006. Translational resistance of late alphavirus mRNA to eIF2alpha phosphorylation: a strategy to overcome the antiviral effect of protein kinase PKR. Genes Dev 20:87–100. doi: 10.1101/gad.357006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toribio R, Ventoso I. 2010. Inhibition of host translation by virus infection in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:9837–9842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004110107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panas MD, Varjak M, Lulla A, Eng KE, Merits A, Karlsson Hedestam GB, McInerney GM. 2012. Sequestration of G3BP coupled with efficient translation inhibits stress granules in Semliki Forest virus infection. Mol Biol Cell 23:4701–4712. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-08-0619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCormick C, Khaperskyy DA. 2017. Translation inhibition and stress granules in the antiviral immune response. Nat Rev Immunol 17:647–660. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DY, Reynaud JM, Rasalouskaya A, Akhrymuk I, Mobley JA, Frolov I, Frolova EI. 2016. New World and Old World alphaviruses have evolved to exploit different components of stress granules, FXR and G3BP proteins, for assembly of viral replication complexes. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005810. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toribio R, Diaz-Lopez I, Boskovic J, Ventoso I. 2016. An RNA trapping mechanism in Alphavirus mRNA promotes ribosome stalling and translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res 44:4368–4380. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rumenapf T, Strauss EG, Strauss JH. 1994. Subgenomic mRNA of Aura alphavirus is packaged into virions. J Virol 68:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rumenapf T, Strauss EG, Strauss JH. 1995. Aura virus is a New World representative of Sindbis-like viruses. Virology 208:621–633. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman HL, Kohlhapp FJ, Zloza A. 2015. Oncolytic viruses: a new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 14:642–662. doi: 10.1038/nrd4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blalock WL, Bavelloni A, Piazzi M, Faenza I, Cocco L. 2010. A role for PKR in hematologic malignancies. J Cell Physiol 223:572–591. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hii SI, Hardy L, Crough T, Payne EJ, Grimmett K, Gill D, McMillan NA. 2004. Loss of PKR activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int J Cancer 109:329–335. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe T, Imamura T, Hiasa Y. 2018. Roles of protein kinase R in cancer: potential as a therapeutic target. Cancer Sci 109:919–925. doi: 10.1111/cas.13551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mundschau LJ, Faller DV. 1992. Oncogenic ras induces an inhibitor of double-stranded RNA-dependent eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha-kinase activation. J Biol Chem 267:23092–23098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mundschau LJ, Faller DV. 1994. Endogenous inhibitors of the dsRNA-dependent eIF-2 alpha protein kinase PKR in normal and ras-transformed cells. Biochimie 76:792–800. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tseng JC, Levin B, Hurtado A, Yee H, Perez de Castro I, Jimenez M, Shamamian P, Jin R, Novick RP, Pellicer A, Meruelo D. 2004. Systemic tumor targeting and killing by Sindbis viral vectors. Nat Biotechnol 22:70–77. doi: 10.1038/nbt917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vähä-Koskela MJV, Kallio JP, Jansson LC, Heikkilä JE, Zakhartchenko VA, Kallajoki MA, Kähäri V-M, Hinkkanen AE. 2006. Oncolytic capacity of attenuated replicative Semliki Forest virus in human melanoma xenografts in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Cancer Res 66:7185–7194. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang PY, Guo JH, Hwang LH. 2012. Oncolytic Sindbis virus targets tumors defective in the interferon response and induces significant bystander antitumor immunity in vivo. Mol Ther 20:298–305. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lundstrom K. 2017. Oncolytic alphaviruses in cancer immunotherapy. Vaccines (Basel) 5:E9. doi: 10.3390/vaccines5020009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin Y, Zhang H, Liang J, Li K, Zhu W, Fu L, Wang F, Zheng X, Shi H, Wu S, Xiao X, Chen L, Tang L, Yan M, Yang X, Tan Y, Qiu P, Huang Y, Yin W, Su X, Hu H, Hu J, Yan G. 2014. Identification and characterization of alphavirus M1 as a selective oncolytic virus targeting ZAP-defective human cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E4504–E4512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408759111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilks N, Kedersha N, Ayodele M, Shen L, Stoecklin G, Dember LM, Anderson P. 2004. Stress granule assembly is mediated by prion-like aggregation of TIA-1. Mol Biol Cell 15:5383–5398. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e04-08-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romano PR, Zhang F, Tan SL, Garcia-Barrio MT, Katze MG, Dever TE, Hinnebusch AG. 1998. Inhibition of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR by vaccinia virus E3: role of complex formation and the E3 N-terminal domain. Mol Cell Biol 18:7304–7316. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myskiw C, Arsenio J, van Bruggen R, Deschambault Y, Cao J. 2009. Vaccinia virus E3 suppresses expression of diverse cytokines through inhibition of the PKR, NF-kappaB, and IRF3 pathways. J Virol 83:6757–6768. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02570-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang YL, Reis LF, Pavlovic J, Aguzzi A, Schafer R, Kumar A, Williams BR, Aguet M, Weissmann C. 1995. Deficient signaling in mice devoid of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. EMBO J 14:6095–6106. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McFadden G, Mohamed MR, Rahman MM, Bartee E. 2009. Cytokine determinants of viral tropism. Nat Rev Immunol 9:645–655. doi: 10.1038/nri2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart WE II, Scott WD, Sulkin SE. 1969. Relative sensitivities of viruses to different species of interferon. J Virol 4:147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryman KD, Klimstra WB, Nguyen KB, Biron CA, Johnston RE. 2000. Alpha/beta interferon protects adult mice from fatal Sindbis virus infection and is an important determinant of cell and tissue tropism. J Virol 74:3366–3378. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3366-3378.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akhrymuk I, Frolov I, Frolova EI. 2016. Both RIG-I and MDA5 detect alphavirus replication in concentration-dependent mode. Virology 487:230–241. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frolova EI, Fayzulin RZ, Cook SH, Griffin DE, Rice CM, Frolov I. 2002. Roles of nonstructural protein nsP2 and alpha/beta interferons in determining the outcome of Sindbis virus infection. J Virol 76:11254–11264. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.22.11254-11264.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molina-Jimenez F, Benedicto I, Dao Thi VL, Gondar V, Lavillette D, Marin JJ, Briz O, Moreno-Otero R, Aldabe R, Baumert TF, Cosset FL, Lopez-Cabrera M, Majano PL. 2012. Matrigel-embedded 3D culture of Huh-7 cells as a hepatocyte-like polarized system to study hepatitis C virus cycle. Virology 425:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Broutier L, Mastrogiovanni G, Verstegen MM, Francies HE, Gavarro LM, Bradshaw CR, Allen GE, Arnes-Benito R, Sidorova O, Gaspersz MP, Georgakopoulos N, Koo BK, Dietmann S, Davies SE, Praseedom RK, Lieshout R, IJzermans JNM, Wigmore SJ, Saeb-Parsy K, Garnett MJ, van der Laan LJ, Huch M. 2017. Human primary liver cancer-derived organoid cultures for disease modeling and drug screening. Nat Med 23:1424–1435. doi: 10.1038/nm.4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blalock WL, Bavelloni A, Piazzi M, Tagliavini F, Faenza I, Martelli AM, Follo MY, Cocco L. 2011. Multiple forms of PKR present in the nuclei of acute leukemia cells represent an active kinase that is responsive to stress. Leukemia 25:236–245. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weber F, Wagner V, Rasmussen SB, Hartmann R, Paludan SR. 2006. Double-stranded RNA is produced by positive-strand RNA viruses and DNA viruses but not in detectable amounts by negative-strand RNA viruses. J Virol 80:5059–5064. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.5059-5064.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forrester NL, Palacios G, Tesh RB, Savji N, Guzman H, Sherman M, Weaver SC, Lipkin WI. 2012. Genome-scale phylogeny of the alphavirus genus suggests a marine origin. J Virol 86:2729–2738. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05591-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nasar F, Palacios G, Gorchakov RV, Guzman H, Da Rosa AP, Savji N, Popov VL, Sherman MB, Lipkin WI, Tesh RB, Weaver SC. 2012. Eilat virus, a unique alphavirus with host range restricted to insects by RNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:14622–14627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204787109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ying L, Cheng H, Xiong XW, Yuan L, Peng ZH, Wen ZW, Ka LJ, Xiao X, Jing C, Qian TY, Liang GZ, Mei YG, Bo ZW, Liang P. 2017. Interferon alpha antagonizes the anti-hepatoma activity of the oncolytic virus M1 by stimulating anti-viral immunity. Oncotarget 8:24694–24705. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee YS, Kunkeaw N, Lee YS. 23 June 2019. Protein kinase R and its cellular regulators in cancer: an active player or a surveillant? Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA doi: 10.1002/wrna.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]