Abstract

Objectives:

To explore how prevalent body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is among Arab dermatology patients and what characteristics of patients are associated with it.

Methods:

A total of 497 patients from the dermatology outpatient clinic at King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, participated in this cross-sectional study conducted between October and December 2018. We asked the patients about their demographic and clinical characteristics, and then asked them to complete a dermatology-based self-report BDD questionnaire. Following this, we appointed 2 independent researchers to evaluate the dermatological flaws highlighted in the patient questionnaires and rate them using a severity scale.

Results:

Body dysmorphic disorder was found in 14.1% of Arab dermatology patients. There were significant links between female with BDD (odds ration [OR]: 2.93; 95% CI 1.24, 6.9]), having 2 or more skin conditions with BDD (OR: 4.67; 95% CI 1.33, 16.49) and having a certain skin condition such as hyperpigmentation with BDD (OR: 5.86; 95% CI 1.46, 23.61). The biggest BDD concerns were hyperpigmentation, acne, and hair loss.

Conclusion:

Body dysmorphic disorder was common among Arab dermatology patients, especially among women and those who have hyperpigmentation or more than one skin condition.

Keywords: body dysmorphic disorder, dermatology, Arab

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) has been understood as a psychiatric condition since 1886, when Enrico Morselli described it as dysmorphophobia.1 The definition of BDD under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria is “excessive preoccupation with an imaginary or minor defect in a facial feature or localized part of the body.2 Most BDD patients believe their assessment of their physical appearance to be accurate; they can spend between 3 and 8 hours a day obsessing over it, unable to control it. Body dysmorphic disorder significantly reduces sufferers’ quality of life (QoL), putting it on a par with or even below the QoL of those who have depression, type II diabetes or who have recently suffered a heart attack (myocardial infarction).3 A lot of BDD patients are unable to work or attend school, so they become cut off socially, even housebound. About a third of BDD patients get so desperate that they self-multilate, hacking at their skin with dangerous implements such as needles, razor blades or knives, and sometimes causing life-threatening complications.4

Body dysmorphic disorder patients are commonly delusional about their perceived physical flaws, often failing to see that they need psychiatric treatment.5 Further, the nature of the preoccupation is such that most BDD sufferers consider their perception to be the true one, meaning that they are more likely to seek the help of a dermatologist or plastic surgeon to correct the physical problem than to visit a psychiatrist. Those with BDD often put themselves through drastic treatments in an attempt to improve their appearance, despite the issue being largely all in their mind.6,7

Many studies have looked into the presence of BDD in different populations. Its incidence in general clinics is reported as 0.7% to 2.4 %, which rises to 9% to 12% in general dermatology clinics and 8% to 37% in cosmetic dermatology clinics.8,9 It is not surprising that BDD is talked about more in general and cosmetic dermatology clinics, as those places by definition focus on the skin and its health and appearance. However, despite there being a lot more information about and discussion of BDD these days, it is still unclear how far cultural background affects BDD patients’ understanding.10 For instance, one study of BDD prevalence in rural Saudi dermatology patients lacked objectivity in its evaluation of patients’ concerns, which makes diagnosing and managing the condition more problematic.11

Methods

At the Dermatology Outpatient Clinic, King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, we conducted a cross-sectional study between October and December 2018. We distributed questionnaires to 600 patients. We excluded patients age <18, >65, or unable to complete a self-report questionnaire. We obtained approval for the study from the Institutional Review Board, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The BDD questionnaire

We asked the patients to provide details of their demography the dermatological condition that prompted them to seek treatment and their history of mental illness, if any. Then, we asked them to complete a validated self-report BDD questionnaire (BDDQ), based on DSM-IV criteria BDD.12 Body dysmorphic disorder questionnaire has 100% sensitivity and 92.3% specificity in cosmetic dermatology practice, with a positive predictive value of 70% and a negative predictive value of 100%. We translated the BDDQ from English into Arabic then back into English, before having it checked by a certified translator. We also revised the BDDQ several times following a review by healthcare professionals (physicians, pharmacists), university professors, and dermatology patients, to assure its validity, accuracy, and clarity.

Objective assessment of the existing defect

We appointed 2 independent researchers to evaluate the BDDQ responses, rating any dermatological flaws reported using a severity scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = nonexistent defect, 2 = slight defect, 3 = defect recognizable from conversational distance, 4 = moderately severe defect and 5 = severe defect).12 We considered that those patients with a score below 3 to have BDD.

Statistical analysis

We described the results of the study categorical variables as frequencies, and we used Chi-square test to conduct univariate analyses of those variables. We included those with a p-value of less than 0.1 in a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis, and calculated odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We considered all p-values of less than 0.05 statistically significant. We performed all analyses using SPSS 21 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

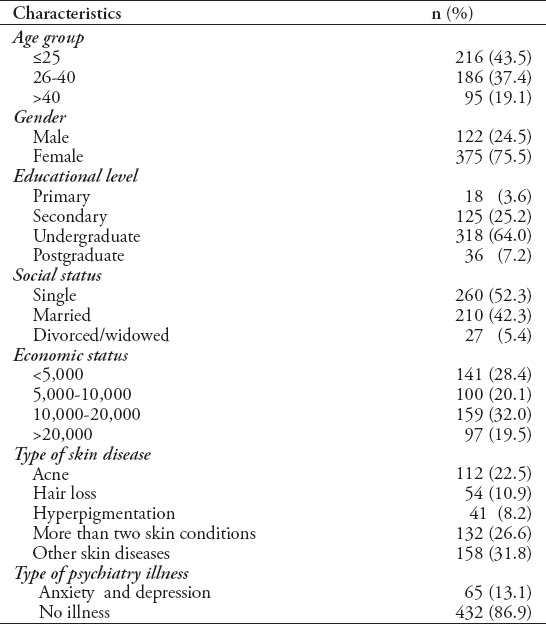

Of the 600 BDDQs issued, 497 were completed the questionnaire, providing a response rate of 83%. Of the respondents, 375 (75.5%) were female, 402 (80.9%) were aged 18 to 40. A total of 365 (73.4%) respondents had a single dermatological disease such as acne, hair loss, hyperpigmentation, and others skin diseases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study subjects (n=497).

Of the total patients, 302 (60.7%) reported being very worried about flaws or physical features they thought were unattractive and 162 (32.5%) felt themselves to be preoccupied by these concerns. Of these 162, 70 (14.1%) screened positive for BDD: 16 (22.9%) said it hampered their social life, 8 (11.4%) found it impaired their schoolwork or job, and 35 (50%) said they avoided doing things because of it.

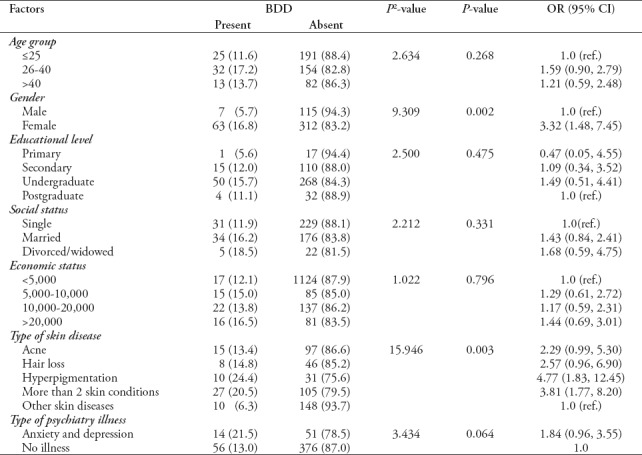

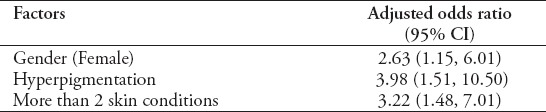

The multivariate analysis found significantly increased likelihood of screening positive for BDD in females (OR 2.93 [95% CI 1.24,6.92]), those with 2 or more skin conditions (OR 4.67 [95% CI 1.33,16.49]) and those with a particular skin condition such as hyperpigmentation (OR 5.86 [95% CI 1.46,23.61]) (Tables 2 & 3).

Table 2.

Associated factors of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) (bivariate analysis).

Table 3.

Independent associated factors of body dysmorphic disorder (multivariate binary logistic regression).

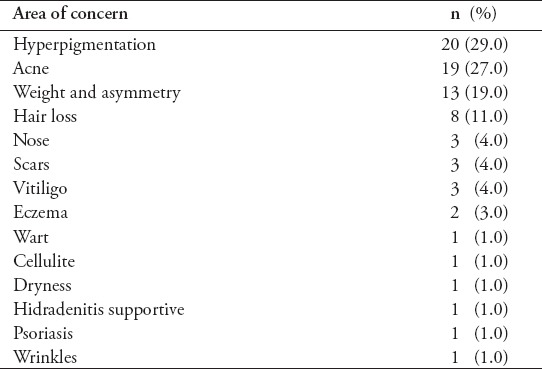

Forty-nine participants (70%) felt that their concern matched the severity of their dermatological complaint, with acne, hyperpigmentation, hair loss and body asymmetry (weight) been the most common areas of concern (Table 4). Approximately 7 patients (10%) had more than one area of concern.

Table 4.

Major areas of body concern in patients diagnosed with body dysmorphic disorder.

Discussion

Body dysmorphic disorder is a psychiatric condition, the main symptom of which is worrying about a slight or nonexistent appearance defect to the point where it prevents the patient from living a normal life. It is distinguished from what may be considered the usual insecurities and self-doubts all humans experience at times by its intensity and its debilitating effect on the patient’s social and professional life.13 Previous studies have found BDD to be common in approximately 1-2% of the general population, although this has recently been shown to be higher (4.4%) among female Saudi students.14 Body dysmorphic disorder is more common in dermatological and cosmetic dermatological settings, too, with reported frequency as high as 53.6%.15-17 And of general dermatology outpatients, approximately 14% screened positive for BDD in America, 7.9% in Germany18,19 and 18.6% in the Alqassim area of Saudi Arabia.20 The Arab prevalence is lower in the current study (14.1%), possibly owing to a lack of objective evaluation of patients’ concerns in the Alqassim study, meaning that patients with moderate and severe physical defects were included in the count.20

There are several reasons why different epidemiological studies show different levels of BDD prevalence, the first of which is the effect of sociocultural differences on body image,21 for example between Arab and Western populations. Second, different BDD screening instruments produce different results. Body dysmorphic disorder questionnaire has been proven to be a validated diagnostic instrument in dermatology patients to screen for BDD. Conrado et al,22 reported that 89% of patients screened positive for BDD with BDDQ, were also diagnosed with BDD using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). Third, BDD results are affected by different study population characteristics; for instance, the relatively high frequency of BDD in general dermatology patients in our current study (14.1%) may be because more patients had conditions associated with BDD, such as acne, hair loss, and hyperpigmentation. Body dysmorphic disorder symptoms tend to begin in early childhood, but it can take 10 to 15 years to be diagnosed properly.23 Although BDD appears more common among women, backed up by the results of the present study, some reports indicate equal frequency in both genders.24 There did not appear to be any correlation between other sociodemographic factors and BDD in this study.

Regarding dermatological conditions, Bowe et al found a 14.1% prevalence of BDD in acne patients when strict criteria were used to diagnose acne and a 21.1% prevalence of BDD when less strict criteria were used.25 For the patients who screened positive for BDD in the present study, hyperpigmentation, which is known to have a significant psychological effect on those with ethnic skin, was the most common skin condition. This is supported by a study of Brazilian BDD patients which found that the most prevalent worry was hyperpigmentation (61.9%), followed by acne.26 One of the findings of note in our present study was that patients who had been diagnosed with 2 or more dermatological conditions were more likely to have BDD than those who had just one skin condition, likely because having multiple conditions makes patients more self-conscious and aware of other minor skin or body flaws.

This study found 7 participants (10%) with BDD who were preoccupied by more than one defect, which fits with similar previous studies,27 as does the patients’ focus on the head/face. However, other studies found that the area of biggest concern for patients was body weight and disproportion.12

Further, 21 (30%) of the patients who screened positive for BDD in our study were not seeking dermatological treatment for their BDD-related issue. This is in line with an existing study in which over 50% of the BDD patients had different actual dermatological conditions from those they were worried about. This was possibly, according to the authors, due to BDD patients are not capable of seeing the true nature of their complaints accurately. Another possible explanation is that BDD patients spend a disproportionate amount of time examining their skin, so they are likely to become aware of any changes more quickly than patients who are not afflicted with BDD. A third reason for BDD patients presenting with unrelated symptoms might be the shame associated with admitting BDD worries to healthcare professionals.28

A recent exploration into the quality of life of BDD patients found a median dermatology life quality index (DLQI) score of 18, reflective of severe impairment.19 Approximately 25% of our BDD patients reported their social life to be negatively affected by their perceived defect and half of them avoided events because of it. Body dysmorphic disorder patients often have other psychiatric conditions, too. A study of hospitalized psychiatric patients found that 16% had BDD, although it had not been previously diagnosed.29 Of our BDD patients, 10 suffered from anxiety, one from depression and 2 from both anxiety and depression, although none had been previously diagnosed with BDD, likely, according to Grant et al because they felt ashamed to talk about it with mental health professionals.30 Thus, we can conclude from our findings that BDD is indeed a secretive, underdiagnosed and undertreated condition.

Study limitations

Several factors may affect interpretation of the results of this study. First, the data does not make use of SCID as a complementary diagnostic measure for psychiatric evaluation, which is a major limitation as it might have been the cause of either overestimation or underestimation of BDD prevalence. There are 6 BDD screening tools commonly recognized in the dermatology setting, one of which is a self-administered tool that was used in this study.31 However, it might have been better to use a combination of psychiatric, psychological, and dermatological evaluations to get a better overall picture and, thus, a more accurate diagnosis. On the other hand, the aforementioned shame and reluctance to discuss the condition experienced by BDD sufferers mean that it might not be possible to convince such patients to seek proper psychiatric evaluation.19,32 The other limiting factor is the scope of the sample. This study focused only on the general dermatology population because in the Saudi health system only medical dermatology services are available; it does not provide cosmetic dermatology. However, this might have skewed the results because it has been well reported that BDD differs in prevalence between general dermatology and cosmetic dermatology settings.12,19

In conclusion, our study confirmed the prevalence of BDD among Arab dermatology patients, particularly females and those with hyperpigmentation or more than one skin condition. This is a valuable information, as Gupta and Gupta33 point out that dermatologic treatment is often dissatisfying for patients if there are underlying, undiagnosed body image pathologies. Patients with BDD remain unhappy with their appearance even after dermatological treatment, which, in extreme cases, can lead them to self-harm or even commit suicide. This makes it crucial to take their concerns seriously, even if their perceived defect is considered simple. Body dysmorphic disorder is not a trivial matter; BDD patients ought not to have their concerns minimized and they ought not to be fobbed off with unnecessary appearing-enhancing procedures; rather, according to Phillips and Dufresne, they should be referred for psychiatric treatment alongside being helped to learn about their disorder.34 And, as the first port of call in most cases, it is equally vital that dermatologists are sufficiently aware of BDD and able to recommend appropriate care.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the College of Medicine Research Center, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Schieber K, Kollei I, de Zwaan M, Martin A. Classification of body dysmorphic disorder - what is the advantage of the new DSM-5 criteria? J Psychosom Res. 2015;78:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toh WL, Castle DJ, Mountjoy RL, Buchanan B, Farhall J, Rossell SL. Insight in body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) relative to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and psychotic disorders:Revisiting this issue in light of DSM-5. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;77:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider SC, Turner CM, Storch EA, Hudson JL. Body dysmorphic disorder symptoms and quality of life:The role of clinical and demographic variables. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2019;21:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins S, Wysong A. Cosmetic surgery and body dysmorphic disorder-An update. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;4:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Uribe-Viloria N, Alonso-Sanchez A, Perez SC, Garcia MG, Calzon MD, Gallego HD, Astorga AA, Ojeda GM, De Cegama FD. Body dysmorphic disorder:Classification challenges and variants. European Psychiatry. 2017;41:S459. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thanveer F, Khunger N. Screening for body dysmorphic disorder in a dermatology outpatient setting at a tertiary care centre. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2016;9:188–191. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.191649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribeiro RV. Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in plastic surgery and dermatology patients:A systematic review with meta-analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:964–970. doi: 10.1007/s00266-017-0869-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veale D, Gledhill LJ, Christodoulou P, Hodsoll J. Body dysmorphic disorder in different settings:A systematic review and estimated weighted prevalence. Body Image. 2016;18:168–186. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg JL, Weingarden H, Wilhelm S. A Practical Guide to Managing Body Dysmorphic Disorder in the Cosmetic Surgery Setting. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019;21:181–182. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh AR, Veale D. Understanding and treating body dysmorphic disorder. Indian journal of psychiatry. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61(Suppl 1):S131–S135. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_528_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonazi H, Alharbi M, Alyousif L, Alialaswad W, Alharbi J, Almalki M, et al. Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in patients attending dermatology clinic in Saudi Arabia/Qassim Region. JMSCR. 2017;11:30471–30479. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dogruk Kacar S, Ozuguz P, Bagcioglu E, Coskun KS, Uzel Tas H, Polat S, et al. The frequency of body dysmorphic disorder in dermatology and cosmetic dermatology clinics:a study from Turkey. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:433–438. doi: 10.1111/ced.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gieler T, Schmutzer G, Braehler E, Schut C, Peters E, Kupfer J. Shadows of beauty-prevalence of body dysmorphic concerns in Germany is increasing:data from two representative samples from 2002 and 2013. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2016;96:83–90. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaffi Ahamed S, Enani J, Alfaraidi L, Sannari L, Algain R, Alsawah Z, et al. Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder and its association with body features in female medical students in Iran. J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2016;10(2):e3868. doi: 10.17795/ijpbs-3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felix GA, de Brito MJ, Nahas FX, Tavares H, Cordás TA, Dini GM, Ferreira LM. Patients with mild to moderate body dysmorphic disorder may benefit from rhinoplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:646–654. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarwer DB. Body image, cosmetic surgery, and minimally invasive treatments. Body Image. 2019;31:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhn H, Mennella C, Magid M, Stamu-O'Brien C, Kroumpouzos G. Psychocutaneous disease:Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:779–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marron SE, Miranda-Sivelo A, Tomas-Aragones L, Rodriguez-Cerdeira C, Tribo-Boixaro MJ, Garcia-Bustinduy M, et al. Body dysmorphic disorder in patients with acne:a multicentre study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Sep 13; doi: 10.1111/jdv.15954. doi:10.1111/jdv.15954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brohede S, Wyon Y, Wingren G, Wijma B, Wijma K. Body dysmorphic disorder in female Swedish dermatology patients. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:1387–1394. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bucchianeri MM, Fernandes N, Loth K, Hannan PJ, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Body dissatisfaction:are associations with disordered eating and psychological well-being similar in adolescents from different racial/ethnic backgrounds? Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2016;22:137. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danesh M, Beroukhim KO, Nguyen C, Levin E, Koo J. Body dysmorphic disorder screening tools for the dermatologist:a systematic review. Pract Dermatol. 2015;2:44–449. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly MM, Phillips KA. Update on Body Dysmorphic Disorder:Clinical Features, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Assessment, and Treatment. Psychiatric Annals 201. 47:552–558. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider SC, Mond J, Turner CM, Hudson JL. Sex differences in the presentation of body dysmorphic disorder in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child &Adolescent Psychology. 2019;48:516–528. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1321001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marron SE, Gracia-Cazaña T, Miranda-Sivelo A, Lamas-Diaz S, Tomas-Aragones L. Screening for body dysmorphic disorders in acne patients:A pilot study. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2019;110:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akinboro AO, Adelufosi AO, Onayemi O, Asaolu SO. Body dysmorphic disorder in patients attending a dermatology clinic in Nigeria:sociodemographic and clinical correlates. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:422–428. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20197919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips KA. Handbook on Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Arlington, Virginia (USA): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015. Body dysmorphic disorder; pp. 57–98. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brohede S, Wijma B, Wijma K. 'I will be at death's door and realize that I've wasted maybe half of my life on one body part':the experience of living with body dysmorphic disorder. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20:191–198. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2016.1197273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veale D, Akyüz EU, Hodsoll J. Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder on a psychiatric inpatient ward and the value of a screening question. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230:383–386. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weingarden H, Renshaw KD, Wilhelm S, Tangney JP, DiMauro J. Anxiety and shame as risk factors for depression, suicidality, and functional impairment in body dysmorphic disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204:832–839. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips KA. Assessment of Body Dysmorphic Disorder:Screening, Diagnosis, Severity, and Insight. Body Dysmorphic Disorder:Advances in Research and Clinical Practice. 2017;12:205–225. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dogruk Kacar S, Ozuguz P, Bagcioglu E, Coskun KS, Polat S, Karaca S, et al. Frequency of body dysmorphic disorder among patients with complaints of hair loss. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:425–429. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomas-Aragones L, Marron SE. Body image and body dysmorphic concerns. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:47–50. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McAndrew R, Sorenson E, Koo J. Therapeutic interventions for body dysmorphic disorder. In: Vashi N, editor. Beauty and body dysmorphic disorder. Berlin: Springer, Cham; 2015. [Google Scholar]