Abstract

Background:

With the substantial growth in the biomedical research literature, a larger number of claims are published daily, some of which seemingly disagree with or contradict prior claims on the same topics. Resolving such contradictions is critical to advancing our understanding of human disease and developing effective treatments. Automated text analysis techniques can facilitate such analysis by extracting claims from the literature, flagging those that are potentially contradictory, and identifying any study characteristics that may explain such contradictions.

Methods:

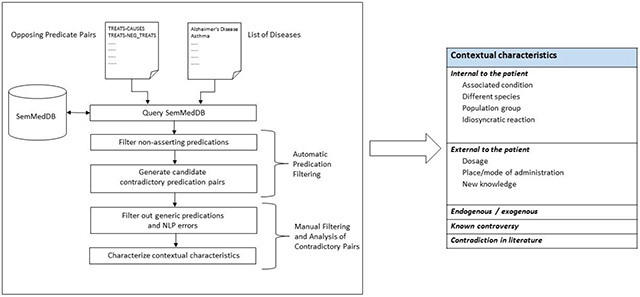

Using SemMedDB, our own PubMed-scale repository of semantic predications (subject-relation-object triples), we identified apparent contradictions in the biomedical research literature and developed a categorization of contextual characteristics that explain such contradictions. Clinically relevant semantic predications relating to 20 diseases and involving opposing predicate pairs (e.g., an intervention treats or causes a disease) were retrieved from SemMedDB. After addressing inference, uncertainty, generic concepts, and NLP errors through automatic and manual filtering steps, a set of apparent contradictions were identified and characterized.

Results:

We retrieved 117,676 predication instances from 62,360 PubMed abstracts (Jan 1980-Dec 2016). From these instances, automatic filtering steps generated 2,236 candidate contradictory pairs. Through manual analysis, we determined that 58 of these pairs (2.6%) were apparent contradictions. We identified five main categories of contextual characteristics that explain these contradictions: a) internal to the patient, b) external to the patient, c) endogenous/exogenous, d) known controversy, and (e) contradictions in literature. Categories (a) and (b) were subcategorized further (e.g., species, dosage) and accounted for the bulk of the contradictory information.

Conclusions:

Semantic predications, by accounting for lexical variability, and SemMedDB, owing to its literature scale, can support identification and elucidation of potentially contradictory claims across the biomedical domain. Further filtering and classification steps are needed to distinguish among them the true contradictory claims. The ability to detect contradictions automatically can facilitate important biomedical knowledge management tasks, such as tracking and verifying scientific claims, summarizing research on a given topic, identifying knowledge gaps, and assessing evidence for systematic reviews, with potential benefits to the scientific community. Future work will focus on automating these steps for fully automatic recognition of contradictions from the biomedical research literature.

Keywords: Contradictions, biomedical research literature, natural language processing, semantic relations

Graphical abstract

1. Background

Scientific publications can be seen as records of knowledge claims on a research question, supported by empirical evidence [1]. Publication of a scientific article is sometimes followed by subsequent studies that either dispute some claims of the original study or reach opposite conclusions on the same research question [2]. Such disagreements are common in clinical research, and can have serious consequences for clinical practice. In a study of 49 highly cited clinical studies, Ioannidis [2] found that out of 45 that claimed effectiveness of an intervention, seven (16%) were contradicted later, and another seven reported initial stronger effects than found in subsequent research. For example, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) which claimed beneficial effects of vitamin E in patients with coronary disease [3] was later contradicted by another RCT that found no apparent effect of this vitamin on cardiovascular outcomes [4]. Another well-known example concerns the use of aspirin in preventing cardiovascular events [5].

Due to the size and significant growth of the biomedical research literature, understanding knowledge claims for a research question can be a complex task. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses in clinical research aim to address this issue by assessing clinical evidence, identifying contradictory claims, and presenting them as a summary. The significant manual effort and time involved in such studies have led researchers to automated and semi-automated text mining methods for some aspects of the systematic review process, such as study screening [6, 7]. Natural language processing (NLP) methods that can support other, more complex aspects of systematic reviews (e.g., extracting key knowledge claims, whether two claims are contradictory, proof of evidence) remain largely understudied [8]. However, methods have been developed for core NLP tasks, such as relation/event extraction [9], detection of relation/event attributes such as knowledge type, polarity, certainty, and factuality [10–13], and explicit claim identification [14], and they could serve as building blocks in addressing such complex information access/management needs. As disagreements and controversies are fairly common in biomedicine, contradictions have garnered some interest from the biomedical text mining (BioNLP) community in recent years, along with conflicting statements and contrasts [15–19]. Research in this area has primarily focused on definition and detection of contradictions and on construction of contradiction corpora. It has been suggested that automatic detection of contradictions could assist in systematic review authoring and literature surveillance [18].

In this work, we approach contradictions within the framework of our semantic relation extraction system, SemRep [20], which extracts semantic predications (subject-relation-object triples) from PubMed abstracts. For example, from the sentence in (1), SemRep extracts the predication in (2). Note that in all example sentences presented in this manuscript, predication arguments are underlined and predicate triggers are in bold:

-

(1)

Bevantolol administered once daily or twice daily was equally effective in the management of hypertension … [in patients] [PMID 2871784]

-

(2)

Bevantolol -treats-Hypertensive disease

SemRep is rule-based and exploits biomedical domain knowledge encoded in the UMLS (Unified Medical Language System) [21] to extract semantic predications. In (1), predication arguments Bevantolol and Hypertensive disease are UMLS Metathesaurus concepts and are identified by MetaMap [22]. The predicate treats comes from the UMLS Semantic Network and is identified by a rule that maps management to that predicate. A knowledge claim, in essence, can be viewed as analogous to a semantic predication or a group of connected predications.

SemRep can extract seemingly contradictory predications. Compare the predication in (4) extracted from the sentence in (3) below with the predication (2) above:

-

(3)

Bevantolol caused hypertension in pithed rats, an effect attenuated by phentolamine, implying that bevantolol may be an alpha-adrenoceptor agonist. [PMID 2858236]

-

(4)

Bevantolol -causes- Hypertensive disease

While predications (2) and (4) have the same subject and object arguments, (4) expresses a causal relationship (causes), and (2) a therapeutic one (treats). The contradiction is resolved when we recognize that the sentences in (1) and (3) differ in terms of species under discussion: the same medication (Bevantolol) has a positive effect in humans (inferred from the abstract) in (1) but a negative effect in rats (pithed rats) in (3). By normalizing a claim into a triple representation, SemRep provides the ability to study knowledge claims and their contradictions beyond a single article across the entire biomedical literature.

We use SemRep to process the entire PubMed database and store the extracted predications in the SemMedDB repository [23]. In its most recent release (up to Jun 30, 2018), SemMedDB contains more than 96 million predications extracted from more than 28 million PubMed abstracts.

In this study, our objective is to investigate the feasibility of using clinically relevant semantic predications to detect contradictory claims in the biomedical literature and to identify the additional processing steps that are involved in reaching this goal. Recognizing that not all seemingly contradictory pairs of predications represent true contradictions but can be explained by their contextual characteristics (such as different species and different modes of administration in (1) and (3)), we also aim to develop a categorization of such characteristics. In conjunction with the literature-scale knowledge stored in the SemMedDB repository and the additional steps identified in this study, this categorization lays the groundwork for methods that can automatically identify clinically relevant contradictions in the biomedical literature. such methods, in turn, can be incorporated into literature surveillance tools that can track and compare knowledge claims [8], and identify knowledge gaps [24] and controversies, offering tangible benefits to the scientific community in managing and conducting research.

2. Related Work

Early research on contradictory/contrastive statements was mainly on negation, the most basic linguistic phenomena used to indicate a contradiction. For example, BioContrasts [15] used handcrafted rules and statements of the form “protein1 but not protein2” to build a database of contrasting protein pairs and the presupposed property for the contrast. They did not include complex contrasts involving relations.

In a study of contradictions in protein-protein interactions (PPIs), Sanchez [16] distinguished explicit and implicit contradictions, the former referring to cases in which authors explicitly state that their results contradict or differ from earlier findings, and the latter referring to those in which a PPI is expressed affirmatively in one publication but negatively or speculatively in another. To detect implicit contradictions, a specific PPI semantic representation was used, consisting of participating proteins and attributes like polarity, direction, certainty, organism, and anatomical locations. Contradictory statements were defined by the value combinations of direction, manner, and polarity encoded in a decision table.

Sarafraz [17] investigated conflicting statements involving biological events in molecular biology literature, and distinguished contradictions from contrasts. Two events were considered contradictory if they shared event type, participants, and anatomical locations, and both were assertive but differed in polarity. Conversely, contrasts differed in event participant or anatomical location, as well as in polarity. She also distinguished three types of contradictions: a) logical contradiction in biology (the notion that a statementp and its opposite ¬p are true simultaneously), b) contradiction in the literature (two statements report opposite facts: e.g., p53 is expressed in mouse lung tissue vs. p53 is never expressed in mouse lung tissue), and c) contradiction in extracted data (two statements are apparently contradictory due to incomplete context: e.g., p53 is expressed in mouse lung tissue at 36C vs. p53 is not expressed in mouse lung tissue). She detected contradicting events by computing their polarity. Applying her method at literature scale (10.9 million abstracts from 2011 MEDLINE baseline and 235,000 full-text articles from PubMed Central), she identified more than 70K conflicting event statements. An analysis of the top-ranking 50 pairs and supporting affirmative and negative sentences showed that most conflicts were due to underspecified context, including differences in species, temporal context, and environmental phenomena. While semantically more precise than in [16], this approach has limitations, as it was limited to negation only, no gene/protein normalization was performed, thus failing to account for lexical variability for these terms, and context analysis was limited to a single event. Furthermore, the biological events considered are a small fraction of the relations in the biomedical literature. As a resource in the development of automatic approaches for contradiction detection, Alamri and Stevenson [18] constructed a small corpus (259 abstracts) of potentially contradictory claims from 24 systematic reviews on cardiovascular research. Presented with a yes/no question on the main topic of a systematic review (e.g., “In women with pre-eclampsia, is mutation in renin-angiotensin gene associated with pre-eclampsia?”), annotators provided a yes/no answer after identifying the claim about the question in the relevant abstracts. Two claims that supported different answers to the question were considered potentially contradictory. There was high inter-annotator agreement in claim sentence identification (92%) and answer annotation (97%). A limitation of the corpus is that claims were not normalized, rendering a literature-scale analysis difficult. Acronyms and other normalization issues were noted as problems facing automatic detection of contradictory claims. Alamri [19] later proposed an automated method for generating a corpus of contradictions based on SemMedDB [23]. He categorized the relation types in SemMedDB into three groups: excitatory (augments, causes), inhibitory (disrupts, prevents), and other (e.g., administered_to, occurs_in). Four types of contradictions were defined based on this grouping:

Subject A-<any excitatory relation Y>-Object B vs. Subject A -NEG_Y- Object B

Subject A-<any excitatory relation>-Object B vs. Subject A-<any inhibitory relation>-Object B

Subject A-<any inhibitory relation R>-Object B vs. Subject A -NEG_R- Object B

Subject A-<other relation X>-Object B vs. Subject A -NEG_X- Object B

For example, in the contradiction pair involving relations of the form A-<any excitatory relation>-B vs. A-<any inhibitory relation>-B, A and B indicate the same specific subject and object arguments. Subject-object pairs relevant to 13 systematic review topics were manually identified. In conjunction with the four types of contradictions shown above, these pairs were then used to search SemMedDB, which led to the identification of contradictory pairs from 526 sentences. Natural language processing (NLP) errors were noted as a limitation of this semi-automatically generated corpus, which was used to develop support vector machine (SVM) models to detect contradictory claims based on n-grams, and lexicon-based negation, sentiment, and directionality features. The model trained on the automatically generated corpus led to a small performance degradation compared to the model trained on the manually annotated corpus, supporting their hypothesis that SemMedDB can be useful for automatically generating this type of corpus.

Beyond the biomedical domain, contradictions have mostly been studied in research on textual entailment. Harabagiu et al. [25] considered two statements as contradictory when one asserts a proposition and the other negates it. They recognized such statements by measuring textual entailment between them after removing negation. They also used linguistic features, such as antonyms, negations, and contrastive discourse relations, and applied their methods to question answering. A looser definition of contradiction was provided in de Marneffe et al. [26], by which two sentences are contradictory if they involve the same event but are extremely unlikely to be true at the same time. With this definition, later adopted in Alamri and Stevenson [18], they categorized several types linguistic constructions that lead to contradictions, such as antonyms, negation, numerical expressions, factivity (verbs such as “believe”), and world knowledge. They used features based on these constructions, among others, to detect contradictions in an annotated corpus of contradictions. Their detection performance was usually low, especially for cases involving world knowledge and factivity. More recently, Bowman et al. [27] introduced a large-scale corpus of contradictions and entailments, and several other contradiction detection approaches using entailment datasets have been proposed [28, 29].

Like Alamri [19], we also use SemMedDB in this work. However, in addition to semi-automatically generating a corpus of potential contradictions, we also investigate the contextual characteristics that provide plausible explanations for apparent contradictions. Also like Alamri [19], but unlike Sarafraz [17], we account for lexical variability in claims since we use SemRep predications, and we do not limit ourselves to negation. Lastly, we focus on clinically relevant predications, largely extracted from the pre-clinical and clinical research literature, for feasibility and also because contradictory claims in these areas can have more direct consequences for human health and wellbeing.

3. Methods

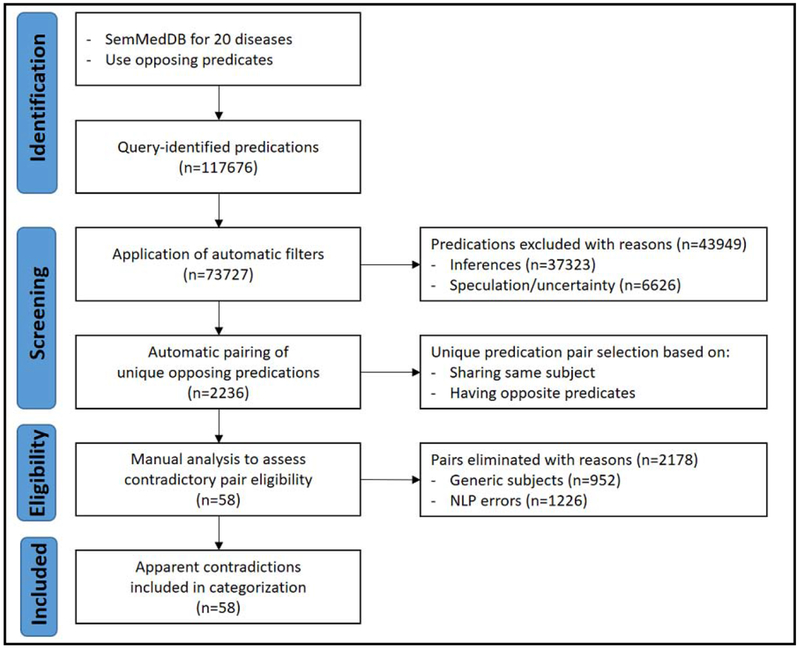

Semantic predications extracted by SemRep from PubMed abstracts and stored in the SemMedDB repository formed the basis of our study. We proceeded in five steps, illustrated in Figure 1:

Query SemMedDB to retrieve clinically relevant predications related to 20 common disorders (Section 3.1)

Automatically filtering out non-asserting predications, considered unlikely to be useful in contradiction analysis (3.2)

Pair remaining predications to generate a set of candidate contradictory predication pairs (3.3)

Manually filter candidate pairs that involve generic concepts as arguments or NLP errors (3.4)

Characterize and quantify plausible explanations for the remaining pairs (3.5)

Figure 1.

PRISMA-style flow diagram for our study.

3.1. SemMedDB retrieval

For feasibility of subsequent analysis, we limited our study to 20 common disorders (Table 1) corresponding to various clinical-physiological systems (i.e., endocrinology, cardiovascular, respiratory, neurology). For our queries, we used a single UMLS Metathesaurus concept associated with each disease. For example, the UMLS contains two concepts corresponding to breast cancer: ‘Malignant Neoplasm of Breast’ (CUI C0006142) and ‘Breast Carcinoma’ (CUI C0678222). In such cases, we chose the concept that was involved in more predications in SemMedDB (‘Malignant Neoplasm of Breast’ for breast cancer).

Table 1.

UMLS Metathesaurus CUIs and preferred names for the disorders selected.

| CUI | Disorder Preferred Name | CUI | Disorder Preferred Name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0002395 | Alzheimer’s Disease | C1269683 | Major Depressive Disorder | |

| C0004096 | Asthma | C0006142 | Malignant neoplasm of breast | |

| C0004352 | Autistic Disorder | C0007102 | Malignant tumor of colon | |

| C0038454 | Cerebrovascular accident | C0149931 | Migraine Disorders | |

| C0011860 | Diabetes Mellitus, Non-Insulin-Dependent | C0027051 | Myocardial Infarction | |

| C0017168 | Gastroesophageal reflux disease | C0028754 | Obesity | |

| C0018801 | Heart failure | C0030567 | Parkinson Disease | |

| C0020443 | Hypercholesterolemia | C0600139 | Prostate carcinoma | |

| C0020538 | Hypertensive disease | C0003873 | Rheumatoid Arthritis | |

| C0021390 | Inflammatory Bowel Diseases | C0917801 | Sleeplessness |

We also identified clinically relevant predicate pairs that can indicate contradiction when used with the same subject-object argument pair (opposing predicates, henceforth). We focused on treats and prevents predicates, as well as causes and predisposes, which can indicate semantic opposition with the former two. Negated counterparts of these predicates (e.g., neg_treats) were also considered, leading to eight opposing predicates, shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Opposing predicates used in this study

| Predicate pairs involving causality | Predicate pairs involving lack of causality |

|---|---|

| treats versus causes (a disease) | treats versus neg_treats (a disease) |

| prevents versus causes | prevents versus neg_prevents |

| treats versus predisposes | causes versus neg_causes |

| prevents versus predisposes | predisposes versus neg_predisposes |

We then queried SemMedDB (release 30) to retrieve predication instances in which the object argument is one of the 20 disorders in Table 1 and the predicate is one of the predicates in Table 2. We also retrieved the sentences supporting these predications to enable subsequent analysis. We provide the SQL query templates used in this step as Supplementary Material, Additional file A.

3.2. Filtering non-asserting predications

We automatically eliminated two types of non-asserting predications (inferred and uncertain). Such predications do not express categorical statements, and are thus unlikely to be useful in the analysis of contradictions.

First, we ruled out predications generated by SemRep via inference rules [30]. One such rule, for example, stipulates that if a drug A treats a population group B, and a disease C is observed in that population B, then the drug A treats the disease C. For example, from the sentence in (5), SemRep generates the inferred predication in (6), which is not explicitly asserted in the sentence.

-

(5)

Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on arterial stiffness in patients with hypertension. [PMID 26631058]

-

(6)

Fatty Acids, Omega-3- treats (infer)-Hypertensive disease

Secondly, we eliminated predications expressed with a degree of uncertainty via our factuality analyzer program [31]. Using a linguistically based approach, this program (94.5% accuracy) classifies a semantic predication into one of six categories: Fact, Probable, Possible, Doubtful, Counterfact, and Uncommitted. Predications classified as Probable, Possible, Doubtful, or Uncommitted are considered uncertain. In (7), the causal relationship between Nicotine and Alzheimer’s disease is rendered uncertain (Possible), due to the use of speculate and may.

-

(7)

We speculate that nicotine may have a role in the aetiology of both Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. [PMID 1855016]

-

(8)

Nicotine-causes-Alzheimer’s disease (Possible)

3.3. Generating candidate contradictory predication pairs

The remaining predications were automatically clustered into candidate contradictory predication pairs for each disorder (referred to as candidate pairs henceforth). We stipulated that two predications were potentially contradictory if they satisfied the following constraints:

Share the same disease object (i.e., one of the disorders listed in Table 1)

Share the same subject argument

Have one set of opposing predicates shown in Table 2

Table 3 shows two contradictory predication pairs (treats versus causes and causes versus neg_causes) and examples of supporting sentences. A predication can be supported by one or more sentences, and from one or more PubMed abstracts.

Table 3.

Examples of opposing predication pairs and their supporting sentences.

| First member in predication pair | Second member in predication pair | |

|---|---|---|

| Predications | Nicotine treats Obesity | Nicotine causes Obesity |

| Sentences | Interestingly, nicotine attenuates obesity, but the underlying mechanism is not clear. [PMID 21653710] | Prenatal exposure to nicotine causes postnatal obesity… [PMID 15897477] |

| Predications | Hyperphagia causes Obesity | Hyperphagia neg_causes Obesity |

| Sentences | Growth hormone overexpression in the central nervous system results in hyperphagia-induced obesity associated with insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. [PMID 15616010] | Interestingly, obesity is not due to hyperphagia…but is associated with increased de novo lipogenesis in the liver. [PMID 24619096] |

3.4. Manual filtering

The automated filtering and pairing steps were followed by manual analysis of the candidate pairs and their supporting sentences. To ensure consistency of assessment in the annotation process, two authors (gr and mf) annotated and discussed in detail all pairs associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Next, one author (gr) annotated the other 19 diseases.

Manual analysis revealed the need for manual elimination of some candidate pairs (due to generic subjects) or some supporting sentences (due to NLP errors). We briefly discuss these cases below.

Pairs with generic subjects: To favor unequivocal results, we ruled out opposing predications with class-level subjects, as claims that use generic classes may not apply to all class members. Three types of generic concepts were identified: drug classes (e.g., diuretics, agents), procedure/process classes (e.g., polypharmacy), and other classes (e.g., genes, alleles). We eliminated the pair completely if the subject belonged to one of these classes. For example, the causes vs. prevents pair in ‘Pharmaceutical Preparations-{causes/prevents}-Asthma’ was eliminated.

-

NLP errors:

SemRep precision errors: SemRep’s precision for clinically relevant predications is estimated at ~75% [23]. If SemRep generated a predication in error, we eliminated its supporting sentence (Table 4, row 1). If this was the only sentence supporting a member of the pair, we then discarded the entire candidate pair, as there ceased to be any support for it.

Factuality analyzer errors: We eliminated the supporting sentence if the factuality analyzer failed to recognize that a predication was expressed with uncertainty, as in Table 4, row 2. As with SemRep precision errors above, this could lead to the elimination of the entire pair.

Table 4:

Examples of supporting sentences manually filtered out due to NLP errors. The pair member supported by the sentence is underlined in the third column. SemRep error in the first row is due to not recognizing riskfactor as an indicator. In the second row, the factuality analyzer error is due to failure to recognize Hypothesis as an uncertainty cue.

| Error source | Supporting sentence eliminated | Opposing predicates |

|---|---|---|

| SemRep |

Homocysteine

(Hcy) is a high risk factor for

Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

[PMID 25007951] Predication: Homocysteine- treats -Alzheimer’s disease |

causes- treats |

| Factuality analyzer | Hypothesis regarding amyloid and

zinc in the pathogenesis of

Alzheimer’s

disease… [PMID 2025422] Predication: Zinc- causes -Alzheimer’s disease |

causes- treats |

3.5. Characterizing contradictory pairs

After manual filtering, only apparently contradictory pairs (apparent contradictions henceforth) remained. An example of an apparent contradiction is given below (11), with supporting sentences in (9) and (10). For better readability, we henceforth express opposing predicates in contradictory pairs as {predicate1/predicate2}, where predicate1 refers to the predicate generated for the first member of the pair, and predicate2 refers to the predicate generated for the second member. Additional contextual cues that are not part of the original sentence but are inferred from the abstract are shown in square brackets in this example as well as the rest of the examples, when needed.

-

(9)

Isoproterenol is therefore effective in controlling myocardial failure during acute rejection… [in

] [PMID 1596130]

] [PMID 1596130] -

(10)

Iso induced heart failure and high mortality in

by impairing

fatty acid and glucose uptake, thereby generating a metabolic

deficit. [PMID 28201733]

by impairing

fatty acid and glucose uptake, thereby generating a metabolic

deficit. [PMID 28201733] -

(11)

Isoproterenol-{treats/causes}-heart failure

We analyzed in detail the context of the members of each pair to establish a categorization of contextual characteristics that may explain the apparent contradictions. For example, in the pair in (11), the apparent contradiction can be explained by the different species: while a therapeutic effect of isoproterenol in heart failure was observed in dogs, a causal effect was observed in CKO mice. When the salient information was not in the immediate context of the sentence, we broadened our analysis to the full abstract. Annotators discussed and refined the categories throughout this phase. The resulting categories are discussed and exemplified in the Results section.

4. Results

A summary of the steps taken to identify and characterize apparent contradictions is presented in Figure 1. The SemMedDB query on 20 diseases (Table 1) and eight opposing predicates (Table 2) returned 117,676 predication instances from 62,360 PubMed abstracts from Jan 1980 to Dec 2016. Automated filtering eliminated 43,949 predications (37.4%) between those inferred (37,323; 31.7%) and those labeled uncertain (6,626; 5.7%). The distribution of the remaining predication instances (73,727) by disease is given in Table 5. These instances were paired into 2,236 unique candidate pairs, from 31,469 abstracts. Table 5 shows the pair distribution by disease. The majority of pairs (2,080; 93%) involved opposing causal predicates (e.g., treats vs. causes). Those involving negation (e.g., treats vs. neg_treats) were rare (156 pairs; 7%). Candidate pairs for all diseases and supporting sentences are provided as supplementary Material, Additional file B.

Table 5.

Distribution by disease of predication instances, candidate predication pairs, and the number of abstracts from which they are extracted.

| Disease | Predication instances (n = ) | Candidate predication pairs (n =) | Abstracts (n = ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 2375 | 145 | 854 |

| Asthma | 7443 | 204 | 3310 |

| Autistic Disorder | 157 | 19 | 56 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 7197 | 238 | 1904 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 5418 | 154 | 2223 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 5414 | 41 | 1267 |

| Heart Failure | 2269 | 163 | 3125 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 6569 | 24 | 126 |

| Hypertensive Disease | 324 | 295 | 4835 |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | 9909 | 45 | 526 |

| Major depressive disorder | 1195 | 21 | 449 |

| Malignant neoplasm of breast | 1226 | 159 | 2591 |

| Malignant tumor of colon | 1847 | 30 | 89 |

| Migraine Disorders | 2280 | 53 | 864 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 6119 | 190 | 2968 |

| Obesity | 6535 | 213 | 2657 |

| Parkinson Disease | 2006 | 117 | 929 |

| Prostate Carcinoma | 101 | 5 | 33 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 4864 | 110 | 2515 |

| Sleeplessness | 479 | 10 | 148 |

| TOTAL | 73727 | 2236 | 31469 |

Both annotators independently categorized 145 candidate pairs involving Alzheimer’s disease into three classes: a) pair with generic subject, b) pair with NLP errors, and c) apparent contradiction. The differences were then reconciled and inter-annotator agreement was calculated (Cohen’s κ = 0.92; very good agreement). The rest of the manual analysis was carried out by one annotator (GR). Most pairs were eliminated in manual analysis due to either NLP errors (1,226 pairs; 54.8%) or generic subject arguments (952 pairs; 42.6%). Only pairs labeled apparent contradictions were selected for further analysis (58 of 2,236 pairs: 2.6%). Table 6 shows the manual analysis results.

Table 6.

Results of manual analysis of candidate pairs

| Disease | Candidate pairs | Apparent contradictions | Generic subject | NLP errors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 145 | 0 | 57 | 88 |

| Asthma | 204 | 5 | 93 | 106 |

| Autistic Disorder | 19 | 0 | 5 | 14 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 238 | 6 | 99 | 133 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 154 | 0 | 69 | 85 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 41 | 4 | 13 | 24 |

| Heart Failure | 163 | 7 | 77 | 79 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 24 | 0 | 19 | 5 |

| Hypertensive Disease | 295 | 21 | 111 | 163 |

| Inflammatory Bowel Diseases | 45 | 3 | 20 | 22 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 21 | 0 | 7 | 14 |

| Malignant neoplasm of breast | 159 | 3 | 52 | 104 |

| Malignant tumor of colon | 30 | 0 | 7 | 23 |

| Migraine Disorders | 53 | 0 | 30 | 23 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 190 | 4 | 87 | 99 |

| Obesity | 213 | 5 | 96 | 112 |

| Parkinson Disease | 117 | 0 | 48 | 69 |

| Prostate Carcinoma | 5 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 110 | 0 | 52 | 58 |

| Sleeplessness | 10 | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| TOTAL | 2236 | 58 | 952 | 1226 |

Hypertensive disease had the highest number of apparent contradictions among all diseases (21 pairs; 32.8%), No apparent contradictions (zero pairs) were identified for 11 of the 20 diseases selected, including Diabetes Mellitus, Autistic Disorder, and Parkinson Disease (Table 6). Thus from this point onward, we will only concentrate on the nine diseases with apparent contradictions.

4.1. Elucidating contextual characteristics

Our analysis of contextual characteristics of 58 apparent contradictions led to a categorization into five main classes, two of which were further subcategorized into subtypes (Table 7). As some predication pairs come from sentences that fit more than one category, the 58 opposing pairs can be explained by 70 contextual characteristics.

Table 7.

Types and distribution of contextual characteristics identified from 58 contradictory pairs, with a short description and the example sentence pairs that illustrate them. Additional contextual cues are shown in square brackets.

| Contextual characteristics (Brief description) | Cases (n=) | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Internal to the patient | 43 | |

| Associated

condition (Comorbidities) |

13 | •

…bromocriptine…to

cause vasospasm and

hypertension [in

puerperium] • Successful bromocriptine treatment of hypertension associated with polycystic ovarian disease |

| Different

species (Species-related response) |

24 | •

Hypertension

produced by partial

nephrectomy… [rats] • Partial nephrectomy resulted in resolution of the patien’s hypertension… [humans] |

| Population

group (Population-specific reaction) |

3 | • … very low doses of

estrogen

reduces the associated risk of

stroke [Women under

35] • women … 50 to 79… showed an increased risk of stroke,… estrogen alone or… with progestin |

| Idiosyncratic

reaction (Allergies, pharmacogenetics) |

3 | • Disodium

cromoglycate is a widely used drug in the

treatment of …

asthma • Near-death asthmatic reaction induced by sodium cromoglycate |

| External to the patient | 21 | |

| Dosage (Amount; chronicity of exposure) |

5 | • Interestingly,

nicotine

attenuates

obesity, but the underlying mechanism is not

clear. • Prenatal exposure to nicotine causes postnatal obesity |

| Place/mode of

administration (Oral vs. intravenous, technique) |

15 | • We conclude that

L-arginine

prevents

hypertension during cross-clamping

… [infusion] • … hypertension and tachycardia were produced by icv L-arginine … |

| New

knowledge (Emerging evidence and facts) |

1 | •

Tacrolimus … is widely

used in the organ transplant setting, but not in the

treatment of

IBD • CONCLUSION: oral administration of tacrolimus …has few adverse effects when used to treat IBD |

|

Endogenous/exogenous (Produced by the body or not) |

1 | • Successful

treatment of a morbidly

obese …adolescent with

Williams-Beuren Syndrome by combining… growth

hormone and sibutramine. • Growth hormone overexpression in the central nervous system results in hyperphagia-induced obesity |

|

Known

controversy (Explicit controversy mention) |

3 | • Estrogens also have been used to treat breast cancer which seems puzzling, since there is convincing evidence to support a link between high lifetime estrogen exposure and increased breast cancer risk. |

|

Contradiction in

literature (No discernible contextual factor) |

2 | • Interestingly,

obesity is not due to

hyperphagia or decreased energy

expenditure • Growth hormone overexpression …results in hyperphagia-induced obesity … |

| TOTAL | 70 |

Characteristics internal to the patient

Contradictions in this category are due to some inherent patient characteristic, instantiated by one or more of the four subtypes discussed below.

Associated Condition:

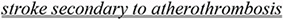

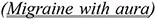

Contradictions in this subcategory can be paraphrased as: “if a condition Z is not associated with any other disease, intervention X has a given effect; otherwise it can have the opposite effect.” In the examples that follow, the associated conditions atherothrombosis (12) and migraine with aura (13) can explain the apparent contradiction in (14). Note that double underlined is used to indicate the contextual information present in the sentences.

-

(12)

Aspirin reduces the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and death

. [PMID

2271790]

. [PMID

2271790] -

(13)

By contrast, our data suggest that women with MA

on aspirin had increased

risk of MI. [PMID

21673005]

on aspirin had increased

risk of MI. [PMID

21673005] -

(14)

Aspirin-{prevents/predisposes}-Myocardial Infarction

Different species:

In biomedical research, different species often respond differently to the same intervention. In the extreme case, the effect observed in one species is the opposite of that in another. In the examples below, a therapeutic effect is observed in rats (16), but an adverse effect is observed in humans in (15), which is explicitly mentioned in the full abstract but not in this sentence.

-

(15)

Severe hypertension induced by naloxone. [in

] [PMID

2931022]

] [PMID

2931022] -

(16)

Naloxone attenuates development of hypertension in DOCA-salt hypertensive

. [PMID

2022070]

. [PMID

2022070] -

(17)

Naloxone-{causes/treats}-Hypertensive Disease

Specific population groups:

The same intervention may affect different population groups in a different way, even within the same species. Tacrolimus evokes one type of response in children and a different one in patients having undergone organ transplantation.

-

(18)

Safety and efficacy of oral tacrolimus in the treatment of

inflammatory bowel

disease. [PMID 19427822]

inflammatory bowel

disease. [PMID 19427822] -

(19)

Pre-transplant inflammatory bowel disease and the use of tacrolimus were found to be independent predictors for inflammatory bowel disease

. [PMID

12848624]

. [PMID

12848624] -

(20)

Tacrolimus-{treats/predisposes}-Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Idiosyncratic reaction:

Unusual reactions to certain drugs are common in clinical medicine and are often attributed to allergies or a patient’s pharmacogenomic make-up. At times, drugs commonly used for a given disease can unexpectedly cause it, as illustrated below, where an established agent in the treatment and prevention of asthma (21), provokes an asthma attack (22). This patient’s medical history revealed a specific paradoxical idiosyncratic reaction.

-

(21)

Disodium cromoglycate is a

in the treatment of allergy and

asthma. [PMID

3117863]

in the treatment of allergy and

asthma. [PMID

3117863] -

(22)

asthmatic

asthmatic

was induced by disodium

cromoglycate… [PMID

9030998]

was induced by disodium

cromoglycate… [PMID

9030998] -

(23)

Disodium cromoglycate-{treats/causes}–Asthma

Characteristics external to the patient

A factor external to the patient may account for an apparent contradiction. We found three subtypes: dosage (amount, length of time, type of exposure); place or mode of administration (e.g., whether a medication is given by itself or in combination with other drugs, technique used, and so on), and new knowledge over time due to new evidence or information regarding a claim.

Dosage / amount:

Contradictions often involve regular versus excessive doses of a medication, or chronicity of exposure versus a therapeutic application, as in (24), where the same sentence specifies that estrogen can both treat (treat) or predispose (increased risk) breast cancer depending on the length of exposure. Other issues such as the endogenous-exogenous dichotomy (explained later) may be involved in this example, as quite frequently multiple factors are at play.

-

(24)

Estrogens also have been used to treat breast cancer which seems puzzling, since there is convincing evidence to support

increased breast cancer risk.

[PMID 23392570]

increased breast cancer risk.

[PMID 23392570] -

(25)

Progesterone-{treats/predisposes}-Malignant neoplasm of breast

Place/mode of administration:

A pharmacologic substance may have different effects depending on the anatomical site of administration, method, or technique used. Below, different ways of administering the same substance trigger opposite effects in rats. L-arginine was administered by infusion in (26) (gleaned from the full abstract), but by an intracerebroventricular injection (icv) in (27):

-

(26)

We conclude that L-arginine prevents hypertension… [infusion] [PMID 7649574]

-

(27)

… hypertension and tachycardia were produced by

L-arginine…

[PMID 11243210]

L-arginine…

[PMID 11243210] -

(28)

L-Arginine-{prevents-causes}-Hypertensive Disease

New knowledge:

New facts arise as knowledge evolves over time, or new evidence emerges. In a 2003 publication, Tacrolimus is an untested application for inflammatory bowel disease (29), while a 2004 publication gives evidence for its effectiveness in this disease, as shown in (30).

-

(29)

Tacrolimus (FK506) is widely used in the organ transplant setting, but not in the treatment of IBD. [PMID 14515846]

-

(30)

Recently, tacrolimus was shown to be effective in mitigating IBD. [PMID 15207535]

-

(31)

Tacrolimus-{neg_treats/treats}-Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Note that (29) is the opening sentence in this abstract. Its conclusion (not shown) asserts that the drug has proven effective for IBD treatment by the study. Thus, the publication of this article [14515846] probably indicates the approximate date when this knowledge became known.

Endogenous versus exogenous characteristics

The endogenous context relates to substances produced by an internal organ or secreted by the body that can be potentially overexpressed under certain conditions. The exogenous context refers to the therapeutic administration of the same substances in therapeutic dosages that can be controlled. Hormones in general are a typical example of this dichotomy:

-

(32)

High

estrogens are well established as

an important cause of breast

cancer, and many known risk factors appear

to operate through this pathway. [PMID

15318928]

estrogens are well established as

an important cause of breast

cancer, and many known risk factors appear

to operate through this pathway. [PMID

15318928] -

(33)

Compared with androgens, progestogens, and glucocorticoids, estrogens have the highest rate of objective response in the treatment of advanced breast cancer… [PMID 6192963]

-

(34)

Estrogens-{causes/treats}-Malignant Neoplasm of Breast

The full article from which (33) was extracted discusses hormonal therapy as an effective breast cancer treatment. Although not specifically mentioned, this indicates an exogenous administration.

Known Controversy

Doubly underlined in the example in (36) is an explicit admission of controversy (similar to Sanchez [16]).

-

(35)

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a synthetic hormone widely used in the adjuvant treatment of advanced breast cancer [in humans] … [PMID 18497975]

-

(36)

The injectable contraceptive, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA, ‘Depo-Provera’), has been

because it caused

malignant mammary tumours in Beagle

dogs. [PMID 8538636]

because it caused

malignant mammary tumours in Beagle

dogs. [PMID 8538636] -

(37)

Medroxyprogesterone acetate-{treats/causes}-Malignant Neoplasm of Breast

Analyses of these abstracts disclose statements admitting controversy about this hormone, e.g., “It is a paradoxical hormone, since it inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation, but has also been implicated in increased breast cancer risk” [PMID 18497975]; “There was some evidence of increased risk [of breast cancer] in certain sub-groups of women…” [PMID 8538636]. The fact that (35) applies to women and (36) to beagle dogs indicates that this is an example of multiple contextual characteristics, namely known controversy and different species.

Contradiction in literature

Sometimes it is not possible to identify a specific contextual characteristic that can account for the apparent contradiction. Without an explicit mention of a controversy in the sentence or in the article, and with all other factors being equal (e.g., same protocol, same species), sentences that instantiate opposing predications could be indicative of a true contradiction, as in Table 3, repeated here, both of which apply to mice:

-

(38)

Interestingly, obesity is not due to hyperphagia or decreased energy expenditure, but is associated with increased de novo lipogenesis in the liver. [PMID 24619096]

-

(39)

Growth hormone overexpression in the central nervous system results in hyperphagia-induced obesity associated with insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. [PMID 15616010]

-

(40)

Hyperphagia-{neg_causes/causes}–Obesity

The distribution of contextual characteristics by disease is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Contextual categorization of 58 apparent contradictions, by disease (A: Asthma, BC: Malignant neoplasm of breast, CVA: Cerebrovascular accident, GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, HF: Heart Failure, HD: Hypertensive Disease, IBD: Inflammatory bowel diseases, MI: Myocardial infarction, OB: Obesity).

| Categories | Disease | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | BC | CVA | GERD | HF | HD | IBD | MI | OB | ||

| Internal to the patient | ||||||||||

| Associated condition | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 13 | |

| Different species | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 14 | 1 | 24 | |||

| Population group | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Idiosyncratic reaction | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| External to the patient | ||||||||||

| Dosage | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | |||||

| Place/mode of administration | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 15 | ||||

| New knowledge | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Endogenous/exogenous | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Known controversy | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Contradiction in literature | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| TOTAL | 5 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 25 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 70 |

It is important to note that for the manual analysis that underpins Table 8, it was only necessary to identify one valid supporting sentence for each member of the contradictory pair before moving on to the next pair. Extending the analysis to all supporting sentences for all pairs would have led to an explosion in the number of sentence combinations to analyze. However, to test the robustness of our proposed categorization and to illustrate the effect of a fuller analysis on the distribution of individual categories, we carried out such an extended analysis for Asthma. The results are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Contextual categorization of all supporting sentences for Asthma apparent contradiction pairs, instantiated by causes-treats, and number of supporting sentences for each pair member.

| Five asthma subjects | Isoproterenol | Aspirin | Cromolyn sodium | formoterol | salmeterol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| causes sentences (n = ) | 1 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| treats sentences (n = ) | 1 | 3 | 19 | 19 | 27 | ||

| Categories | Totals | ||||||

| Internal to the patient | 140 | ||||||

| Associated Condition | 18 | 34 | 1 | 53 | |||

| Idiosyncratic | 34 | 34 | |||||

| Population Group | 8 | 8 | |||||

| Different Species | 1 | 18 | 26 | 45 | |||

| External to the patient | 7 | ||||||

| Dosage amount | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||||

| Place/mode of administration | 1 | 1 | |||||

| New knowledge | 0 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 1 | 21 | 76 | 21 | 28 | 147 | |

Five apparent contradictions were identified for this disease, four of which had multiple supporting sentences for each member of the causes-treats opposition. The fifth pair, with subject Isoproterenol, had only one supporting sentence per pair member. While the proposed contextual characteristics were sufficient to explain the differences between all supporting sentence pairs, the distribution resulting from the extended analysis was different from that from the original manual analysis. Some contradictory sentence pairs could be explained by the External to the patient category, which was not associated with Asthma in the original manual analysis. Additionally, we extended our in-depth analysis of Asthma to those contradictory statements that were labelled possible/probable by the factuality analyzer. The contextual categorization of these extra 24 apparent contradiction pairs did not reveal any new categories from our initial categorization.

We present the full list of 2,236 automatically identified candidate pairs, as well as 58 apparent contradictions, supporting sentences, additional in-depth Asthma analyses, and categorization as Supplementary Material, Additional file C.

5. Discussion

The goal of our study was three-fold. First, we investigated the feasibility of using semantic predications to identify potential contradictions in the biomedical research literature. Our findings largely confirm those in [19], where SemMedDB was used to semi-automatically generate a corpus of contradictory claims. Owing to the fact that semantic predications address lexical variability in textual expressions of biomedical claims and that SemMedDB provides instant access to millions of predications extracted from the entire PubMed database, generating a corpus of potential contradictions for a given concept (disease, drug, procedure, etc.) or a set of concepts is relatively straightforward.

Second, we determined the steps that were required to identify and elucidate apparent contradictions from a set of candidate contradictions. On a small subset of the dataset, the two annotators had very good agreement in classifying candidate pairs based on their characteristics, suggesting that the steps identified were generally applicable. These included steps that are currently automated (filtering out inferred and uncertain predications), and those that are possible to automate (filtering of predications with generic type subjects, such as Genes). In earlier work on automatic summarization [32], we filtered out such broad generic concepts by exploiting the hierarchical structure of UMLS Metathesaurus, and this can be beneficial in this work as well. Other steps are more difficult to automate and involve manual analysis. Similar to Alamri [19], we note that any contradiction recognition tool that relies on NLP needs to take into account errors generated by NLP methods. In this study, we found that 54.8% of all contradictory pairs would have been eliminated if NLP components (SemRep and the factuality analyzer) had perfect accuracy. One potential approach to reduce the burden of manual filtering is to use machine learning to filter incorrect semantic predications, as was done in [33].

Third, we found that a great majority of the apparent contradictions could be explained by appealing to contextual characteristics, for which we presented a categorization more comprehensive than those in earlier works [16, 17]. For example, we have shown that the endogenous/exogenous difference may account for contradictory statements regarding hormones, as in the examples presented earlier in (32) and (33). Another category we introduce is that of Associated condition causing a treatment to have an effect different from that expected, as illustrated by the sentences in (12) and (13). However, we were only able to identify a small number of apparent contradictions (58 pairs) for categorization, and only a few of these (classified as Contradiction in literature or Known controversy) can be considered true contradictions or controversies that reveal a knowledge gap [24] that needs to be addressed with further empirical research.

The small number was due in part to our manual analysis method, in which we stopped analyzing a contradictory pair after one valid supporting sentence for each member of the pair was identified. Performing a manual comparison of all sentence pairs for every disease was not deemed feasible due to the combinatorial nature of the problem. An extended analysis limited to Asthma (Table 9) was encouraging, as the original categorization was sufficient to cover all contradictory cases. The distribution of the categories, on the other hand, differed from the original categorization, and it may be a better reflection of the true distribution of the contextual characteristics. The small number of apparent contradictions may also be partly due to publication bias [34], the notion that negative and contradictory results are less likely to be published. A similar characterization of contradictory evidence and counterarguments is presented by Tatsioni et al. [35], based on a manual analysis of literature on the cardiovascular benefits of vitamin E. They distinguish two types of counterarguments, biases and genuine diversity, the latter of which is organized into PICO classes (Participants, Interventions, Co-Interventions, and Outcomes) and corresponds, roughly, to our categorization of contextual characteristics. Their Participants class is analogous to our Internal to the patient category, Interventions/Co-interventions are subsumed by our Dosage and Place/mode of administration categories. While the Outcome class does not fit neatly in our categorization, their sole Outcome example is a Dosage instance. Further research may be needed to assess this category. Biases include selection bias and information bias, factors that cannot be generally gleaned from the texts of study abstracts and are, thus, outside the scope of our work. Our extended analysis and comparison to Tatsioni et al.’s [35] characterization suggests that our categorization is robust, as far as the clinically relevant relationships we studied are concerned. Our categorization can form the basis of an annotation study, which can in turn inform rule-based or machine learning-based methods for automatic recognition and classification of apparent contradictions. Since the apparent contradictions were found to be a small portion of the candidate pairs (2.6%), a much larger initial set of semantic predications needs to be considered for a useful corpus.

Our analysis also revealed some possible directions for automatic characterization of apparent contradictions. For example, we observed that some contextual characteristics relevant in explaining apparent contradictions could be captured in additional predications from the same sentences or abstracts. Consider the example in (16), where the predication Naloxone-treats-Hypertensive Disease was extracted from the sentence Naloxone attenuates development of hypertension in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. SemRep also extracts the predication Hypertensive Disease-process_of-Rattus norvegicus from the same sentence, and this information could be exploited to infer that the relevant contextual characteristic is Different species. It is also clear that lexical items provide contextual cues for specific context categories (e.g., abuse, chronic, and acute for the Dosage category or controversy and paradoxical for Known controversy) and they could be exploited as well, as it was done in [16]. Finally, we noted that MeSH indexing terms associated with PubMed abstracts (e.g., ‘Rats’ in the example above) provide clues for automatic classification. As an exploratory analysis of how well the entities or predications generated by SemRep or MeSH indexing terms would aid in automatic characterization, we focused on Different species and examined the context for each of the 24 apparent contradictions in this subcategory. We found that the immediate context (i.e., the predication sentence) resolved the contradiction in six cases, either via a process_of predication involving the species or the mention of the species entity itself. In 17 cases, the full abstract needed to be considered for their resolution. In one instance, we could not glean the species information from either the abstract or the MeSH terms. While limited, this analysis suggests that automatic characterization can be achieved almost entirely using already extracted knowledge or the whole abstract, without a need for MeSH indexing terms.

5.1. Limitations of this study

Our study has several limitations. For feasibility of manual analysis, we limited our scope to clinically relevant predications and 20 common diseases. This resulted in a small number of apparent contradictions, making a broad characterization of diseases according to related contradictory / controversial information challenging (although, Hypertension stood out). The fact that our categorization of contextual characteristics was based on a subset of supporting sentences led to a small number of examples for each category, and it is therefore difficult to draw conclusions regarding the true distribution of these characteristics. We mitigated this somewhat by an exhaustive analysis of all the pairs for one disease (Asthma), which confirmed the proposed categorization of characteristics, but also showed that their true distribution may be different from that obtained in this analysis.

Another limitation lies in SemRep recall errors, a source of missed pairs, some of which may constitute apparent contradictions. SemRep recall was reported to be around 55% [23], suggesting that this may be a significant problem in recognizing contradictions. In a small-scale analysis, we tried to replicate Ioannidis’s four contradictions (1 prevents-predisposes, 3 treats-neg_treats) [2] using the abstracts in that work, which correspond to seven contradictory article pairs. since these contradictions involved diseases not considered for the analysis in our manuscript, we extracted semantic predications from the abstracts of these articles using SemRep. We found that the relevant relationships SemRep identified did not coincide with any of the four contradictions in [2]. Issues noted were SemRep missing instances of negation, failure to reconcile roughly equivalent UMLS concepts (e.g., estrogen vs. estrogen use), and relationships spanning multiple sentences. This further confirms that recall errors are a major shortcoming of using SemRep for this purpose. Using concept co-occurrence in conjunction with relation triggers (e.g., therapy, treatment for treats), rather than relying on explicit relationships, may partially address this problem. Another related approach may be to use various types of embeddings (e.g., word [36], sentence [37], or UMLS CUI [38]) to determine sentences likely to yield contradictory information. Note that the UMLS knowledge sources on which SemRep relies have their inherent limitations, and may cause some recall errors as well. We used a single UMLS concept for each disease whereas some diseases can map to several similar UMLS concepts, as mentioned. A more complete analysis should consider such equivalent concepts, which could lead to the identification of a larger set of apparent contradictions. Lastly, in our analysis, we did not make any qualitative distinction between predications extracted from different types of studies providing different levels of evidence, which arguably makes our proposed categorization general, at least as far as clinically relevant knowledge is concerned. However, in a real-world application it may be more preferable to assign lower weight to a contradiction due to a case study finding compared to a contradiction between the findings of two RCTs or systematic reviews. Other publication characteristics, such as journal impact factors, or whether articles are highly cited [2], could also be used to rank contradictory information. Future work should consider such distinctions.

6. Conclusions

We have shown that semantic predications in the SemMedDB repository can be used to automatically identify candidate contradictions and investigate the contextual characteristics that underlie such statements. We found that additional filtering and classification steps were needed to identify true contradictions that may represent knowledge gaps and controversial claims. From more than 117K predications associated with 20 diseases, we automatically identified 2236 candidate pairs, 58 of which (2.6%) were found to be apparent contradictions after manual analysis. Four of these pointed to contradictions in literature or known controversies, making them prime candidates for further empirical studies to resolve. In the light of its precision and recall errors, we conclude that while SemRep can serve as a basis for recognizing contradictory evidence, it needs to be significantly extended with additional resources and methods to be useful in a real-world application.

By using additional opposing predicates relevant to other scientific areas, this method can be generalized to other domains, such as molecular biology (stimulates vs. inhibits) or the influence of genotypes on physiological functions (augments vs. disrupts). Such extensions may reveal additional categories of contextual characteristics. It is also likely that a higher number of contradictions could be identified in other types of studies, such as genetic association studies, in which extreme opposite results are more frequently seen [39].

Future work will focus on improving the automated tools used in the current study (e.g., factuality analyzer), automating some manual processes (e.g., generic subject identification, contextual characteristic classification), and generalizing the approach to other domains. Automatic recognition of contextual characteristics will require a large annotated corpus, which we also plan to construct semi-automatically using SemMedDB.

These steps lay the groundwork for fully automatic recognition of contradictory or conflicting information from the literature. We can envision a literature surveillance tool supported by semantic predications, which can search, verify, and track knowledge claims and the supporting evidence at scale. Such a system can ingest newly published articles by extracting semantic predications from them, compare their claims to its repository of biomedical claims (analogous to SemMedDB), perform relevant filtering and categorization steps, and pinpoint claims in the literature that are in apparent or true contradiction with the current claims. Other potential uses would be to provide pre-publication authoring and peer review assistance by pinpointing manuscript text that potentially conflicts with the existing knowledge and systematic review assistance by allowing a large-scale comparison of claims and evidence on a given topic. Such a system can also send focused alerts/warnings to users, when a new, possibly contradictory claim is made on a topic of interest [8]. In addition, as suggested above, two categories (Known controversy and Contradiction in literature) can indicate knowledge gaps and point out potential new research directions. More broadly, such a system can help address the problem of communication gap [24] between scientists working in different areas (so-called research silos), by highlighting relevant claims and evidence from subdomains that a scientist may not typically interact with, contributing to the overall efficiency of biomedical research and discovery.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Semantic predications can be used to automatically identify candidate contradictions in the biomedical literature

Automatic and manual filtering steps are needed to identify apparent contradictions from candidates

A categorization of the contextual characteristics that explain apparent contradictions or indicate true contradictions is presented

Acknowledgements

We thank Thomas C. Rindflesch for his contributions in early stages of this study. We are also grateful to Catherine Blake and Dimitar Hristovski for their insightful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the intramural research program at the U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included as Supplementary Material.

Competing Interests

None.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Marcelo Fiszman, Email: fiszmanm@gmail.com.

Dongwook Shin, Email: shindongwoo@mail.nlm.nih.gov.

Halil Kilicoglu, Email: halil@illinois.edu.

References

- 1.Clark T, Ciccarese P, Goble C. Micropublications: a semantic model for claims, evidence, arguments and annotations in biomedical communications. Journal of Biomedical Semantics, 51 2014:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ioannidis JP. Contradicted and initially stronger effects in highly cited clinical research. JAMA. 2005; 294(2):218–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephens NG, Parsons A, Brown MJ, Schofield PM, Kelly F, Cheeseman K, Mitchinson MJ. Randomised controlled trial of vitamin E in patients with coronary disease: Cambridge Heart Antioxidant Study (CHAOS). The Lancet. 1996;347(9004):781–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yusuf S, Dagenais G, Pogue J, Bosch J, Sleight P. Vitamin E supplementation and cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The New England journal of medicine. 2000; 342(3):154–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, Cricelli C, Darius H, Gorelick PB, Howard G, Pearson TA, Rothwell PM, Ruilope LM, Tendera M. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1036–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Mara-Eves A, Thomas J, McNaught J, Miwa M, Ananiadou S. Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: a systematic review of current approaches. Systematic Reviews 4(1), 2015: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jonnalagadda SR, Goyal P, Huffman MD. Automating data extraction in systematic reviews: a systematic review. Systematic Reviews 2015; 4:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilicoglu H. Biomedical text mining for research rigor and integrity: tasks, challenges, directions. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 2017(a). bbx057, doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo Y, Uzuner Ö, Szolovits P. Bridging semantics and syntax with graph algorithms—state-of-the-art of extracting biomedical relations. Briefings in Bioinformatics 18(1) 2016: 160–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson P, Nawaz R, McNaught J, Ananiadou S. Enriching a biomedical event corpus with meta-knowledge annotation. BMC bioinformatics 12(1), 2011: 393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miwa M, Thompson P, McNaught J, Kell DB, Ananiadou S. Extracting semantically enriched events from biomedical literature. BMC Bioinformatics 13(1), 2012: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kilicoglu H, Bergler S. Biological event composition. BMC bioinformatics 13(11), 2012: S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilicoglu H, Rosemblat G, Cairelli MJ, Rindflesch TC. A compositional interpretation of biomedical event factuality. Proc. Second Workshop on Extra-Propositional Aspects of Meaning in Computational Semantics. ExProM 2015: 22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blake C. Beyond genes, proteins, and abstracts: Identifying scientific claims from full-text biomedical articles. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 43(2) 2010: 173–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JJ, Zhang Z, Park HC, Ng SK. BioContrasts: extracting and exploiting protein-protein contrastive relations from biomedical literature. Bioinformatics 22(5); 2005:597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez O. Text mining applied to biological texts: beyond the extraction of protein-protein interactions. PhD diss., University of Essex, 2007ISNI: 0000 0001 3510 7201. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarafraz F. Finding conflicting statements in the biomedical literature.” PhD Diss., University of Manchester, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alamri A, Stevenson M. A corpus of potentially contradictory research claims from cardiovascular research abstracts. Journal of Biomedical Semantics 7(1), 2016: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alamri A. The Detection of Contradictory Claims in Biomedical Abstracts. PhD diss, University of Sheffield, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rindflesch TC, Fiszman M. The interaction of domain knowledge and linguistic structure in natural language processing: interpreting hypernymic propositions in biomedical text. J Biomed Inform. 2003;36(6):462–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodenreider O. The unified medical language system (UMLS): integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D267–D270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aronson A, Lang F. An overview of MetaMap: historical perspective and recent advances. J. Am Med Inform Assoc 2010. May-Jun; 17(3): 229–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilicoglu H, Shin D, Fiszman M, Rosemblat G, Rindflesch TC. SemMed DB: a PubMed-scale repository of biomedical semantic predications. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(23): 3158–3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng Y, Bonifield G, Smalheiser NR. Gaps within the biomedical literature: Initial characterization and assessment of strategies for discovery. Frontiers in research metrics and analytics. 2017;2:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harabagiu S, Hickl A, Lacatusu F. Negation, contrast and contradiction in text processing. In AAAI, vol. 6, 2006: 755–762. [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Marneffe MC, Rafferty AN, Manning CD. Finding Contradictions in Text. In ACL, vol. 8, 2008: 1039–1047. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowman SR, Angeli G, Potts C, Manning CD. A large annotated corpus for learning natural language inference. 2015. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.05326 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritter A, Downey D, Soderland S, Etzioni O. It’s a contradiction---no, it’s not: a case study using functional relations. In Proc. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing Association for Computational Linguistics; 2008:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pham MQN, Nguyen ML, Shimazu A. Using shallow semantic parsing and relation extraction for finding contradiction in text. Proc., International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing 2013: 1017–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rindflesch TC, Pakhomov SV, Fiszman M, Kilicoglu H, Sanchez VR. Medical facts to support inferencing in natural language processing. AMIA Annu Symp Proceedings 2005: 634–638. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kilicoglu H, Rosemblat G, Rindflesch TC. Assigning factuality values to semantic relations extracted from biomedical research literature. PLOS ONE. 2017(b). July 5;12(7):e0179926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiszman M, Kilicoglu H, Rindflesch TC. Abstraction summarization for managing the biomedical research. HLT-NAACL Workshop on Computational Semantics, 2004:76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang R, Adam TJ, Simon G, Cairelli MJ, Rindflesch T, Pakhomov S, Melton GB. Mining Biomedical Literature to Explore Interactions between Cancer Drugs and Dietary Supplements. AMIA Summits on Translational Science Proceedings. 2015;2015:69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fanelli D. Negative results are disappearing from most disciplines and countries. Scientometrics. 2012. March 1;90(3):891–904. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tatsioni A, Bonitsis NG, Ioannidis JP. Persistence of contradicted claims in the literature. JAMA. 2007. December 5;298(21):2517–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiu B, Crichton G, Korhonen A, Pyysalo S. How to train good word embeddings for biomedical NLP. In Proceedings of the 15th Workshop on Biomedical Natural Language Processing 2016. (pp. 166–174). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagliardini M, Gupta P, Jaggi M. Unsupervised learning of sentence embeddings using compositional n-gram features. arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.02507 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newman-Griffis D, Lai AM, Fosler-Lussier E. Jointly Embedding Entities and Text with Distant Supervision. In Proceedings of The Third Workshop on Representation Learning for NLP 2018. (pp. 195–206). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA. Early extreme contradictory estimates may appear in published research: the Proteus phenomenon in molecular genetics research and randomized trials. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2005;58(6):543–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.