Abstract

In normoxic, isolated perfused guinea pig hearts instrumented for measurement of atrioventricular nodal conduction time (AVCT), an analysis utilizing the irreversible A1-adenosine (Ado) antagonist, meta-1,3-phenylene diisothiocyanate xanthine amine cogener (m-DITC-XAC), a novel isothiocyanate derivative of 1,3-dialkylxanthine, was used to investigate whether spare A1-Ado receptors exist in the guinea pig atrioventricular (AV) node and the degree of amplification (reserve) between A1-Ado receptor occupancy and dromotropic response (e.g., AVCT slowing). The potency, dose dependency, and kinetic profile (time dependence of washout and washin) of m-DITC-XAC was determined and compared with those of known competitive (reversible) A1-Ado receptor antagonists. In the presence of m-DITC-XAC, Ado and N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA) produced submaximal dromotropic responses. In a series of 19 hearts, m-DITC-XAC caused 100% apparent antagonism of the effect of Ado on AVCT even after 60 min of washout. In contrast, >90% of 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) and XAC-induced antagonism of the effect of Ado on AVCT dissipated within 35 min. Unlike XAC, which caused maximal attenuation of Ado’s AVCT effect within 5 min and remained constant thereafter, m-DITC-XAC showed marked time- and concentration-dependent behavior. It was found that 5 min of 0.5 μM m-DITC-XAC pretreatment irreversibly inactivated 72% of the A1-Ado receptors mediating the dromotropic effect, and the estimated agonist equilibrium dissociation constant for CPA was 84 ± 4 nM. The percent of spare A1-Ado receptors at the EC50 and extrapolated maximal S-H interval prolongation levels was 20 and 54%, respectively, and the reserve (coupling amplification) varied from 1 to 2.3 within the 0–50% maximal response range. In summary, m-DITC-XAC appears to specifically and irreversibly antagonize the negative dromotropic effect of Ado and CPA, and guinea pig AV nodal tissue possesses spare A1-Ado receptors.

Keywords: adenosine antagonists, coupling mechanism, physiological reserve

ADENOSINE IS AN AUTACOID with numerous regulatory functions in multiple organ systems. In the heart, the effects of adenosine are mediated by at least two subtypes of cell membrane-bound receptors, the A1- and A2-adenosine receptors (2, 30). The overall effect of adenosine in the heart is to normalize the cardiac oxygen demand-supply quotient. That is, A1-adenosine receptors mediate actions that decrease myocardial oxygen consumption (e.g., negative chronotropic effect), whereas A2-adenosine receptors mediate effects that increase oxygen supply by causing coronary vasodilation (3, 25).

Although much is known about the regulatory role of adenosine in cardiac function, the adenosine receptor-effector coupling process remains poorly understood. For instance, while it is well accepted that the cardiac electrophysiological effects of adenosine are mediated by the A1-receptor subtype, the degree of amplification (reserve) between receptor occupancy and response remains unknown in the atrioventricular (AV) node. Likewise, the presence of spare A1-adenosine receptors in AV nodal tissue is yet to be demonstrated. Until recently, the lack of adequate A1-adenosine receptor pharmacological probes, combined with the low density of this receptor in cardiac tissue compared with brain tissue and other receptors (e.g., muscarinic and adrenergic), have hindered characterization of the cardiac A1-adenosine receptor system.

Unlike the first adenosine receptor antagonists identified (i.e., theophylline and caffeine), newer alkylxanthine derivatives are more potent and specific competitive antagonists (5, 6, 8, 12). Despite this and other developmental advances achieved with competitive adenosine antagonists, only recently have their irreversible counterparts been synthesized (4, 13). The advantages of using irreversibly bound ligands for physicochemical characterization of biological systems are multiple and well known (9, 19, 28). Jacobson et al. (13) synthesized irreversible A1-adenosine receptor antagonists by derivatizing functional congeners obtained from 1,3-dipropyl-8-phenylxanthine and N6-phenyladenosine with electrophilic groups. These investigators found a meta-isomer of xanthine isothiocyanate, meta-1,3-phenylene diisothiocyanate xanthine amine congener (m-DITC-XAC), to be the most potent adenosine antagonist derived from XAC (13) and moderately selective for the A1-adenosine receptor.

In the present study, the potency, specificity, and irreversibility of m-DITC-XAC’s antagonism of the atrioventricular nodal conduction delay caused by adenosine (i.e., negative dromotropic effect) in the isolated perfused guinea pig heart was determined, and the results contrasted with those of known competitive A1-adenosine receptor antagonists. A method developed by Furchgott (9) was used to estimate the agonist equilibrium dissociation constant (KA) of the selective A1-adenosine receptor agonist, N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA). Results of the mathematical analyses were correlated with functional data to determine 1) the spare AV nodal receptor capacity and 2) the degree of amplification of the coupling mechanism between A1-adenosine receptor occupancy and dromotropic response.

METHODS

Chemicals

Adenosine, CPA, 8-cyclopentyltheophylline (CPT), and carbamylcholine chloride (carbachol) were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). m-DITC-XAC was synthesized by Dr. K. A. Jacobson (13). XAC and 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) were purchased from Research Biochemicals (Natick, MA).

Isolated Perfused Heart Preparations

Experiments were carried out in adult guinea pig hearts (Hartley) of either sex weighing 250–300 g. After being anesthetized with methoxyflurane (by inhalation), the animals were killed by cervical dislocation. The heart was then quickly excised and rinsed in ice-cold modified Krebs-Henseleit (K-H) solution. The aorta was cannulated and perfused retrogradely at a constant flow of 8 ml/min with oxygenated (95% O2-5% CO2) K-H solution at 35 ± 0.5°C. The composition of the K-H solution (in mM) is 117.9 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.18 MgSO4, 1.18 KH2PO4, 2.0 pyruvate, 5.5 glucose, 0.57 NaEDTA, 0.007 ascorbic acid, and 25.0 NaHCO3. The Po2 and pH of the K-H solution were maintained at 500–600 mmHg and 7.3–7.4, respectively.

The depressant effect of adenosine on atrioventricular nodal (AV node) conduction time (i.e., negative dromotropic effect) was measured at a constant rate of atrial pacing. A constant pacing atrial cycle length is necessary because AV nodal conduction is modulated by atrial rate, which in turn is affected by adenosine. The sinoatrial nodel region (including venae cavae) and part of the right atrium were excised to facilitate electrical pacing and expose the AV nodal area. A unipolar extracellular electrode was placed in the AV nodal area to record the His bundle electrogram (HBE) according to a previously described method (14). The hearts were electrically paced at an atrial cycle length (ACL) of 330 ms (3 Hz) via a bipolar electrode placed on the interatrial septum. The stimulator, an interval generator (WPI model 1830), delivered stimuli via a stimulus isolation unit (WPI model 1880) as square-wave pulses of 3 ms in duration and twice threshold intensity. Measurements of AV nodal conduction time were made from HBE during constant atrial pacing. Because adenosine primarily acts on the proximal area of the AV node (7), either the atrial-to-His bundle (A-H) or stimulus-to-His-bundle (S-H) interval may be used as a measure of its effect on AV nodal conduction. The S-H interval was measured from the HBE using an automated on-line data acquisition program (Snapshot storage scope, HEM Data, Southfield, MI) or visually from the oscilloscope display at a sweep speed of 10 ms/cm.

After dissection, trimming, and instrumentation (i.e., placement of electrodes) were completed, the hearts were allowed to equilibrate for 30–45 min before the experiments were started. Experimental interventions were always preceded and followed by measurements of S-H intervals. Whenever pre- and post-control values differed by >15% after washout, the intervening experimental data were discarded. Likewise, if any of the interventions caused the stimulus-to-atrial interval (i.e., normally 2–5 ms in guinea pig hearts) to prolong above baseline values by >3 ms, the data were discarded. Unless otherwise noted, if any of the interventions caused second or third degree AV block, the most stable measured response value (longest S-H interval) before the onset of AV block was used for data analysis. The maximal S-H interval prolongation before onset of AV block was used as a the maximum dromotropic effect (i.e., maximal response). This method of analyses may have slightly underestimated the true concentration of adenosine (or its analogues) required to produce AV block (maximal effect) and thereby slightly overestimate the percent spare AV nodal A1-adenosine receptors at 100% response. However, because the difference between the concentration that causes maximal S-H interval prolongation and second degree AV block is small (i.e., <1.2-fold), the potential error in the estimation of percent spare receptors should be minimal. On the other hand, this potential error will not affect the analysis that determines the physiological reserve (coupling amplification between A1-adenosine receptor occupancy and dromotropic response) because the experimental data used for this analysis are well below the maximal response level (i.e., horizontal bars in Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

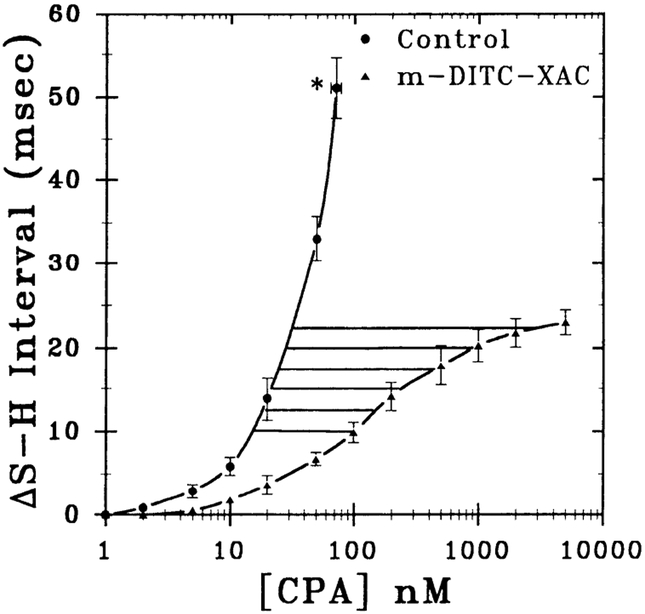

CPA concentration-response curves pre- and posttreatment of guinea pig hearts with m-DITC-XAC. Shown are concentration-response curves for CPA pre- (control, n = 6) and posttreatment (n = 5) of 0.5 μM m-DITC-XAC. Each data point is mean ± SD of several experiments (n). * Maximal response defined as second degree AV block. Six horizontal lines represent equieffective concentrations of CPA in control (i.e., A) and m-DITC-XAC-treated (i.e., A′) hearts at various response levels (ΔS-H interval ranging from 10 to 22.5 ms). Analysis of control heart data revealed an EC50 value of 37 nM, and a ΔS-Hmax value of 51.1 ms occurring at a concentration of 71 nM CPA. Likewise, m-DITC-XAC-treated hearts demonstrated EC50, ΔS-Hmax, and n (slopes) values of 138 ± 7 nM, 23.6 ± 0.3 ms, and 0.93 ± 0.03, respectively.

CPA, CPT, DPCPX, XAC, and m-DITC-XAC were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 10 mM and then kept frozen. On the day of experimentation, these stock solutions were thawed and diluted in 0.9% normal saline. Fresh adenosine and carbachol stock solutions were prepared by dissolving them directly into 0.9% normal saline. Adenosine, carbachol, CPA, CPT, DPCPX, XAC, and m-DITC-XAC stock solutions were then infused into the perfusion line at various flow rates via a Harvard syringe pump to achieve the desired perfusate concentrations.

Protocols

Antagonism of negative dromotropic effect of adenosine by DPCPX, CPT, XAC, and m-DITC-XAC.

In this series of experiments (n = 19), DPCPX, CPT, XAC, and m-DITC-XAC were used to antagonize the negative dromotropic effect of adenosine. In each isolated heart, the perfusate concentration of adenosine was gradually increased until a stable S-H interval prolongation of ~15 ms was achieved. The adenosine antagonist (e.g., DPCPX, CPT, XAC, and m-DITC-XAC) was then concurrently administered in the perfusate at progressively higher concentrations. At each concentration of the antagonist, 5 min was allowed to elapse before recording the new S-H interval. In this manner, concentration-response relationships for the various adenosine receptor antagonist’s ability to attenuate the adenosine-induced AV nodal conduction time prolongation were obtained. Unlike known competitive (reversible) adenosine receptor antagonists (e.g., DPCPX and XAC), the extent of receptor blockade by an irreversible antagonist such as m-DITC-XAC is expected to be time dependent. Thus, for comparative purposes, the isolated hearts were exposed to the adenosine antagonists for 5 min before measurements were made. For example, to minimize m-DITC-XAC’s time-dependent effect, three separate hearts were exposed to 20, 200, and 500 nM sequentially in 5-min intervals, whereas another set of three hearts were treated with the higher m-DITC-XAC concentrations (1 and 5 μM) in the same fashion.

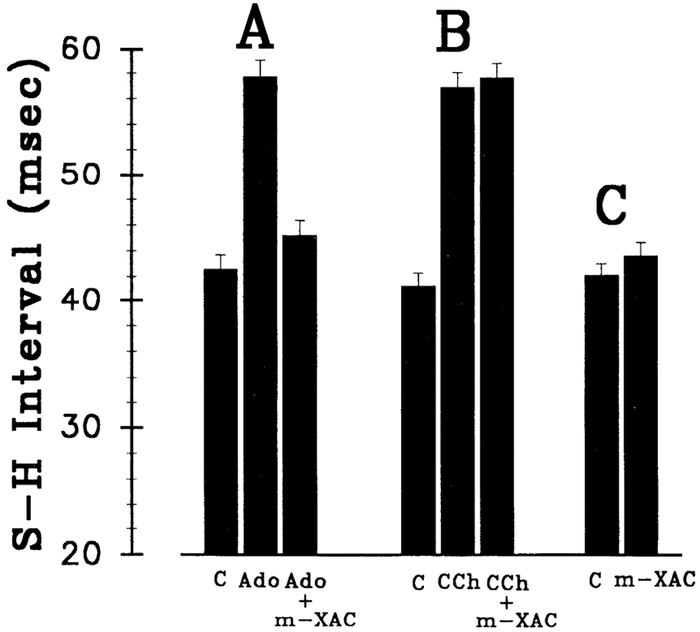

Specificity of m-DITC-XAC antagonism.

In a second series of hearts (n = 15), the ability of m-DITC-XAC to antagonize the negative dromotropic effect of adenosine was compared with that of the muscarinic cholinergic agonist, carbachol. In addition, the effect of m-DITC-XAC on baseline AV nodal conduction time (AVCT) was investigated. For the adenosine (n = 5) and carbachol (n = 5) experiments, in each isolated heart, the perfusate concentration of agonist (adenosine or carbachol) was gradually increased until a stable S-H interval prolongation of ~15 ms was achieved. m-DITC-XAC was then concurrently administered in the perfusate at a concentration of 5 μM for a 5-min period, and the new S-H interval was then recorded. In this manner, the specificity of m-DITC-XAC’s ability to attenuate agonist-induced AV nodal conduction time prolongation was obtained. With regard to the effect of m-DITC-XAC alone on the baseline S-H interval (n = 5), each isolated heart was perfused with m-DITC-XAC at a concentration of 0.5 μM for a period of 60 min, and the new S-H interval was then recorded.

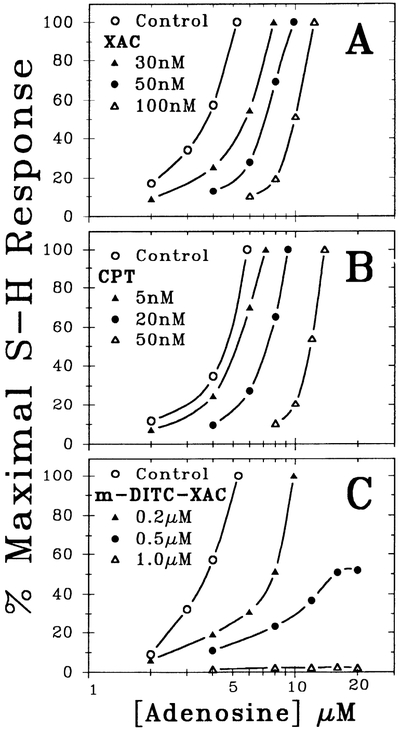

Concentration-response relationships of negative dromotropic effect of adenosine in absence and presence of XAC, CPT, and m-DITC-XAC.

In a third series of hearts (n = 20), the concentration-response relationships of the negative dromotropic effect of adenosine in the absence or presence of XAC, CPT, or m-DITC-XAC was investigated. In any given heart of this series, a control dose-response curve for adenosine was initially determined. After a 5-min washout period of adenosine, a continuous infusion of the adenosine antagonists, i.e., XAC (30, 50, or 100 nM), CPT (5, 20, or 50 nM), and m-DITC-XAC (0.2, 0.5, or 1.0 μM) was started. After a 5-min equilibration period in the presence of the antagonist, another concentration-response curve for adenosine was obtained, followed by a 5-min washout period. In the case of XAC- and CPT-treated hearts, the antagonist perfusate concentration was then increased to the next higher concentration, and the concentration-response curve for adenosine was repeated. Because the extent of m-DITC-XAC’s antagonism is time dependent, a separate group of hearts (n = 4) was used for each perfusate concentration of m-DITC-XAC. Unlike the XAC- and CPT-treated hearts, m-DITC-XAC was infused for 5 min, followed by 30 min of washout, and the dose response for adenosine was obtained.

Washout kinetics of adenosine antagonist effect.

In a fourth series of hearts (n = 19), the washout kinetics (i.e., time dependence) of the adenosine antagonists were determined. In each heart, the perfusate concentration of adenosine was increased until the S-H interval prolonged ~15 ms. After a 5-min washout period of adenosine, the heart was then pretreated for 5 min with an antagonist concentration previously determined to completely attenuate the negative dromotropic effect of adenosine. That is, DPCPX, XAC, and m-DITC-XAC were infused at concentrations of 20 nM, 500 nM, and 5 μM, respectively. Once the antagonist pretreatment period ended the infusion of the antagonist was discontinued, whereas the infusion of adenosine was restarted and maintained for a total of 60 min at the same perfusate concentration known to produce the initial 15-ms S-H interval prolongation. Control hearts were not treated with adenosine antagonist.

Onset kinetics of adenosine antagonist effect.

In a fifth series of 15 hearts, the time course of the onset of action of the adenosine antagonist (attenuation of adenosine’s negative dromotropic effect) was investigated. In each heart, the adenosine perfusate concentration was increased until the S-H interval prolonged ~15 ms. Infusion of the adenosine antagonist (XAC at 10 nM or 30 nM, m-DITC-XAC at 0.05 μM or 0.10 μM) was then started and maintained for a total of 90 min in the continued presence of adenosine. The time dependence of the alkylxanthine’s ability to attenuate adenosine-induced AV nodal conduction time prolongation was then determined. The S-H interval was recorded at various times throughout the 90 min of observation. In this manner, the onset kinetics of XAC effects were contrasted to that of m-DITC-XAC. Because the extent of m-DITC-XAC’s attenuation of adenosine’s negative dromotropic effect is both time and concentration dependent, separate hearts were used for each concentration of m-DITC-XAC, either 0.05 μM (n = 5) or 0.10 μM (n = 5).

Concentration-response curves for CPA in absence and presence of m-DITC-XAC.

In a sixth series of hearts (n = 11), the concentration-response relationships for CPA were obtained pre (control)- and posttreatment with 0.5 μM m-DITC-XAC. In any given heart, a control dose-response curve for CPA was initially obtained. After washout of CPA, the heart was exposed to 0.5 μM m-DITC-XAC for 5 min. After the infusion of m-DITC-XAC was stopped, the heart was perfused for an additional 30 min to ensure complete washout of the antagonist fraction not covalently linked to the A1-adenosine receptor. At this time, another dose-response curve for CPA was obtained.

Data Analysis

Unless otherwise noted, all data are reported as means ± SE of n experiments. Nonbiased IC50 values, representing the concentration of antagonist that attenuates 50% of adenosine (or analogue)-induced S-H interval prolongation, were calculated using weighted (e.g., variance−1) nonlinear regression curve fitting via the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm to a logistic equation (see Eq. 1 in APPENDIX). Similarly, nonbiased EC50 values, representing the concentration of adenosine producing 50% maximal response, were determined by curve fitting the experimental dose-response data to a multiparameter polynomial equation (see Eq. 2 in APPENDIX) using a nonlinear regression algorithm (Marquardt-Levenberg). Dose ratios were then determined at the EC50 level.

RESULTS

Attenuation of Negative Dromotropic Effect of Adenosine by Alkylxanthines

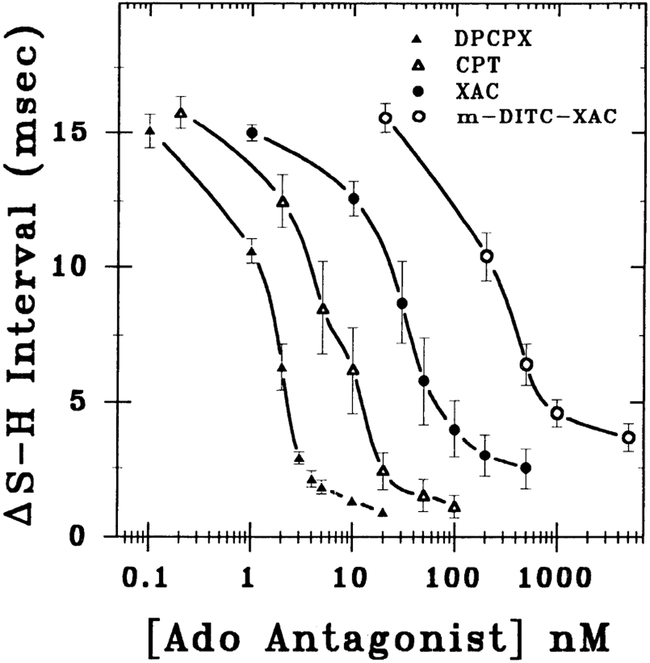

In this series of experiments, the rank-order potency of various alkylxanthines in attenuating the negative dromotropic effect of adenosine was determined. As shown in Fig. 1, DPCPX (n = 5), CPT (n = 3), XAC (n = 5), and m-DITC-XAC (n = 6) dose dependently antagonized an adenosine-induced 15.3 ± 0.3 ms S-H interval prolongation. The concentration of antagonist that attenuated 50% of the adenosine-induced S-H interval prolongation (IC50 value) was determined by curve fitting the data to a general logistical equation (Eq. 1 in APPENDIX). The IC50 values for DPCPX, CPT, XAC, and m-DITC-XAC were 1.2 ± 0.4, 5.3 ± 1.0, 41.3 ± 7.9, and 414 ± 151 nM, respectively. Hence, the rank order of potency is DPCPX > CPT > XAC > m-DITC-XAC. The apparent Hill coefficients varied from 0.9 to 1.3 with an average of 1.1 ± 0.1. Tests for parallelism of the slopes of the concentration-response curves (n values) showed no significant difference.

Fig. 1.

Concentration-response relations for attenuation of the negative dromotropic effect (ΔS-H interval) of adenosine by alkylxanthines in guinea pig heart. Effect of progressively higher concentrations of alkylxanthines [8-cyclopentyl-1,3-diproplxanthine (DPCPX, n = 5); 8-cyclopentyltheophylline (CPT, n = 3); xanthine amine congener (XAC, n = 5); meta-1,3-phenylene diisothiocyanate xanthine (m-DITC-XAC, n = 6)] in antagonizing an adenosine-induced 15 ms S-H interval prolongation is shown. Data are means ± SE. IC50 values for DPCPX, CPT, XAC, and m-DITC-XAC were 1.2 ± 0.4, 5.3 ± 1.0, 41.3 ± 7.9, and 414 ± 151 nM, respectively.

To compare the pharmacological behavior between known competitive (reversible) adenosine antagonists (e.g., XAC and CPT) with that of m-DITC-XAC, adenosine concentration-response relationships were determined in the absence (control) and presence of each adenosine antagonist at progressively higher concentrations. As illustrated in Fig. 2, XAC (A, n = 4) and CPT (B, n = 4) antagonized the S-H interval prolongation caused by adenosine in a manner different from that of m-DITC-XAC (C, n = 12). More specifically, when the hearts were exposed to progressively higher concentrations of m-DITC-XAC, the maximal dromotropic effect of adenosine (i.e., S-H interval prolongation) was also gradually attenuated. That is, 5 min of pretreatment with 0.5 μM of m-DITC-XAC depressed the maximal dromotropic response of adenosine to 50% of control, whereas 5 min of 1.0 μM m-DITC-XAC pretreatment almost abolished the dromotropic effect of adenosine (Fig. 2C). In comparison, increasingly higher concentrations of the competitive adenosine receptor antagonists (XAC and CPT) induce parallel rightward shifts of the adenosine concentration-response relationship and exhibit surmountable antagonism. The concentration-response curves for XAC and CPT from Fig. 2, A and B, were analyzed using Schild plots (27) to determine the pA2 values and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KB) for adenosine antagonists. Schild analysis yielded pA2 values ± SE for CPT and XAC of 7.48 ± 0.01 and 7.23 ± 0.02, respectively. Consequently, the KB values of CPT and XAC were 33 and 59 nM, respectively. Slopes ± SE from the linear regression analysis were −1.01 ± 0.02 and −0.98 ± 0.08 for CPT and XAC, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Concentration-response relations demonstrating antagonism of adenosine’s negative dromotropic effect in guinea pig heart by XAC (A, n = 4), CPT (B, n = 4), and m-DITC-XAC (C, n = 12). Shown are concentration-response curves for adenosine in absence and presence of progressively higher concentration of A1-adenosine receptor antagonists. Maximal response to adenosine is defined as onset of second degree A–V block. Note markedly different pharmacological behavior of two known competitive A1-adenosine receptor antagonists (XAC and CPT) compared with a novel irreversible A1-adenosine receptor antagonist (m-DITC-XAC). Data are depicted as mean values of several experiments (n).

Specificity of m-DITC-XAC

In this series of experiments, the specificity of m-DITC-XAC’s antagonism of the AV nodal actions of adenosine (Fig. 3A) was investigated by contrasting it to that of carbachol (Fig. 3B) and by determining the direct effect of m-DITC-XAC alone on AVCT (i.e., baseline S-H interval; Fig. 3C). Whereas 5 μM m-DITC-XAC caused near complete antagonism of an adenosine (n = 5)-induced S-H interval prolongation (i.e., from 57.7 ± 1.5 to 45.2 ± 1.2 ms), it had no effect on the S-H interval prolongation caused by carbachol (i.e., from 56.9 ± 1.2 to 57.6 ± 1.2 ms; n = 5). In addition, 60 min of treatment with 0.5 μM m-DITC-XAC did not significantly change the baseline S-H interval (i.e., from 42.1 ± 0.9 to 43.6 ± 1.0 ms; n = 5). Thus m-DITC-XAC appears to specifically antagonize the depressant effects of adenosine on the AV node without altering baseline AVCT.

Fig. 3.

Effect of m-DITC-XAC on AV nodal conduction time (AVCT). Shown is the effect of m-DITC-XAC (m-XAC) on an adenosine- (Ado; A, n = 5) and carbachol- (CCh; B, n = 5) induced 15 ms S-H interval prolongation above the control (C) value. Whereas 5 μM m-DITC-XAC nearly abolished adenosine’s negative dromotropic effect, it had no effect on S-H interval prolongation caused by carbachol. As shown in C (n = 5), 0.5 μM m-DITC-XAC alone had no effect on AVCT (i.e., no significant change in the baseline S-H interval). Each bar graph represents mean ± SE.

Washout Kinetics of A1-Adenosine Receptor Antagonists

To determine the irreversibility of m-DITC-XAC as an A1-adenosine receptor antagonist at the functional level, the time dependence of the pharmacological effect of various alkylxanthines was investigated. As shown in Fig. 4A, a 60-min washout time course for the attenuation of adenosine’s negative dromotropic effect by various adenosine antagonists was obtained. Note the markedly different washout time courses. The attenuation of adenosine-induced S-H interval prolongation by DPCPX (n = 4) and XAC (n = 5) dissipated with time (i.e., their antagonism was reversible). In contrast, the antagonistic effect of m-DITC-XAC (n = 5) did not dissipate during the 60 min of observation, a finding consistent with irreversible antagonism. Note how the baseline ΔS-H interval in control hearts drifts upward as a function of time. When a ΔS-H interval drift correction is applied, ~90% of the adenosine-induced S-H interval prolongation had returned to its original value (i.e., obtained in the absence of antagonist) at 35 min of washout time in hearts treated with DPCPX or XAC. Conversely, in hearts pretreated with m-DITC-XAC, adenosine’s effect remained completely inhibited over the same washout period.

Fig. 4.

Kinetics of washout (A) and onset of action (B) of various A1-adenosine receptor antagonists in guinea pig heart. A: time course of adenosine receptor antagonist washout. DPCPX (n = 4), XAC (n = 5), and m-DITC-XAC (n = 5) were infused at concentrations of 20 nM, 500 nM, and 5 μM, respectively. Control hearts (n = 5) were not treated with adenosine receptor antagonist or adenosine. Note markedly different antagonist washout time courses of DPCPX and XAC compared with m-DITC-XAC. B: time course of onset of action of alkylxanthines in attenuating an adenosine-induced 15-ms S-H interval prolongation. Kinetic profile of m-DITC-XAC (0.05 μM or 0.10 μM; n = 10) compared with XAC (10 or 30 nM; n = 5) shows marked time- and concentration-dependent behavior in its onset of action. Data are means ± SE of several experiments (n).

Onset Kinetics of A1-Adenosine Receptor Antagonists

In another series of experiments, the time course of the onset of action for adenosine receptor antagonist-induced attenuation of adenosine’s negative dromotropic effect was investigated. As illustrated in Fig. 4B, the kinetic behavior of XAC (n = 5) markedly differed from that of m-DITC-XAC (n = 10). XAC caused maximal antagonism of the negative dromotropic effect of adenosine within 5 min. Higher concentrations of XAC simply reduce adenosine-induced prolongation of AV nodal conduction time in a parallel (competitive) manner. In contrast, the time course of attenuation by m-DITC-XAC showed marked time and concentration dependence. At a given antagonist exposure time, 0.10 μM m-DITC-XAC (n = 5) compared with 0.05 μM m-DITC-XAC (n = 5) was able to antagonize a greater fraction of the S-H interval prolongation caused by adenosine. Thus, as depicted in Fig. 4B, the curves defining the kinetic profile of m-DITC-XAC at 0.05 and 0.10 μM display marked nonparallelism and converge at 90 min of continuous antagonist perfusion, a finding consistent with 100% antagonism of adenosine’s effect.

Determination of Equilibrium Dissociation Constant (KA) for CPA

In this series of experiments, concentration-response relationships for the negative dromotropic effect of CPA were obtained pre (control)- and posttreatment of hearts with 0.5 μM m-DITC-XAC. CPA is a highly potent and selective A1-adenosine receptor agonist. Unlike adenosine, the negative dromotropic effect of this adenosine analogue is not enhanced by nucleoside uptake inhibitors (e.g., dipyridamole) or enhanced by the adenosine deaminase inhibitor, erythro-9-(2-hydroxy-3-nonyl)adenine HCl (7). This suggests that CPA is not subject to deamination or cellular uptake, which may confound pharmacological analysis (15, 17). Figure 5 illustrates the concentration-response curves for CPA pretreatment (control, n = 6) and posttreatment (n = 5) with 0.5 μM m-DITC-XAC. As previously reported for adenosine and its analogues (7), the shape of the concentration-response relationship of CPA in control hearts was found to be parabolic, whereas that in hearts pretreated with m-DITC-XAC was sigmoidal in shape. A nonbiased numerical description of the control and m-DITC-XAC concentration-response data was obtained by using a least squares, weighted (variance−1) nonlinear regression algorithm fitted to 1) a multiparameter parabolic equation (Eq. 2 in APPENDIX) and 2) a general logistic equation (Eq. 3 in APPENDIX), respectively. Analysis of control data revealed the concentration of CPA producing 50% of the maximal response (EC50 value) to be 37 nM, and the maximal S-H interval prolongation (ΔS-Hmax) of 51.1 ms was obtained at a CPA concentration of 71 nM. In m-DITC-XAC-treated hearts, the EC50, ΔS-Hmax, and slope (n value) were 138 ± 7 nM, 23.6 ± 0.3 ms, and 0.93 ± 0.03, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 5, using the untransformed concentration-response data for CPA (AS-H interval) from control and antagonist-treated hearts via nonlinear curve fitting, nonbiased CPA concentrations at equieffective levels in both control (e.g., A) and m-DITC-XAC (e.g., A′)-treated hearts were obtained. Values of A and A′ were obtained at six equieffective levels of S-H interval prolongation (horizontal lines in Fig. 5) ranging from 10 to 22.5 ms.

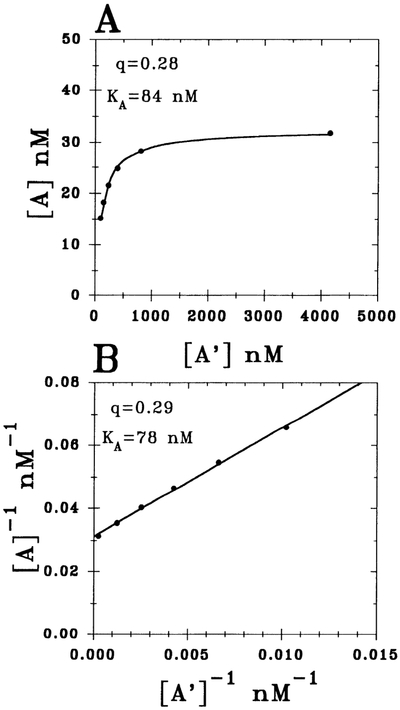

To determine the KA value for CPA, the data obtained in Fig. 5 (i.e., A and A′) were analyzed using two different approaches. As illustrated in Fig. 6, A and A′ values are required for the application of Furchgott’s method of irreversible receptor inactivation (Eq. 4, APPENDIX) for determining the KA. Figure 6A shows the results for the nonlinear analysis of the untransformed raw data (ΔS-H interval vs. concentration of CPA) from Fig. 5 using Furchgott’s equation (Eq. 4, APPENDIX), whereas in Fig. 6B, the equation has been transformed to the more conventional linearized form (Eq. 5, APPENDIX).

Fig. 6.

Determination of CPA’s equilibrium dissociation constant (KA) by applying method of Furchgott to data depicted in Fig. 5 [i.e., equieffective concentrations of CPA in control (A) and m-DITC-XAC-treated (A′) hearts]. A: results of a nonlinear analysis of untransformed experimental data from Fig. 5 using Eq. 4 in APPENDIX. B: findings for linearized version of Eq. 4 (i.e., Eq. 5). Fraction of total receptors remaining after irreversible antagonist treatment and agonist dissociation equilibrium constant are denoted by q and KA, respectively. Both analyses yielded similar results.

The results indicate that a 5-min pretreatment of the heart with 0.5 μM m-DITC-XAC irreversibly inactivated 72% of the functional A1-adenosine receptors (q = 0.28 ± 0.02), and the KA value for CPA was 84 ± 4 nM (Fig. 6A). The value of q represents the fraction of remaining functional A1-adenosine receptors after pretreatment with antagonist. Because the sum of squares for the nonlinear curve fit was 0.36 nM2, the “goodness” of the fit can be considered excellent. Thus the underlying assumption (i.e., law of mass action) was valid in the ΔS-H interval range of 10–22.5 ms. That is, the dependence of A1-adenosine receptor fractional occupancy (ρ) on the concentration of CPA is reliably given by Eq. 6 (see APPENDIX).

As shown in Fig. 6B, the linearized equation form (1/A vs. 1/A′ plot) gave an excellent fit as well. The slope and y intercept is defined by 1/q and (1/KA)[(1 − q)/q], respectively. The linear analysis yielded values for q and KA of 0.29 and 78 nM, respectively. However, for statistical reasons (17), the q and KA values from Fig. 6A (rather than from Fig. 6B) were used in future analyses.

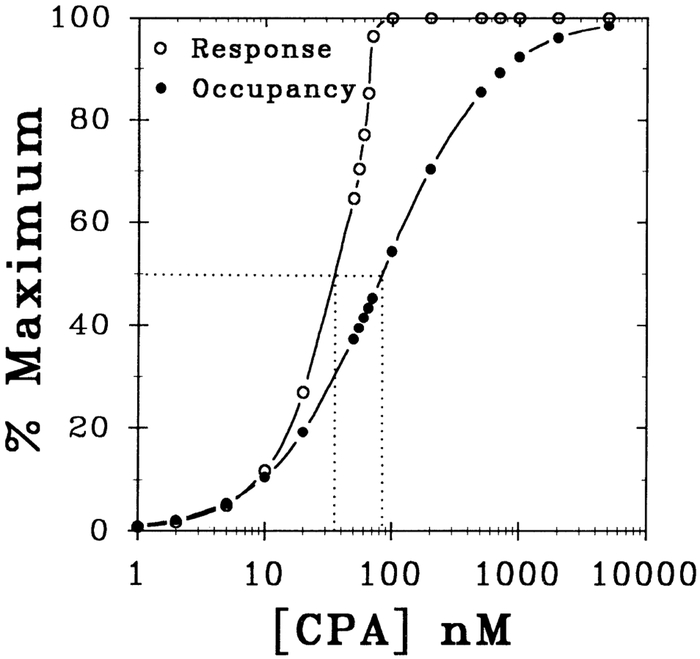

Occupancy-Response Relationships for CPA

To estimate ρ as a function of percent maximal dromotropic response, ρ was calculated using Eq. 6 of the APPENDIX and plotted against the dromotropic response (%maximum) elicited by CPA. Figure 7 shows the dependence of both percent maximal S-H prolongation and the estimated percent maximal A1-adenosine receptor occupancy (%maximum) as a function of the concentration of CPA. The raw control ΔS-H interval data from Fig. 5 were transformed to provide the percent maximal response, and the percent receptor occupancy data were estimated according to the law of mass action (Eq. 6, APPENDIX). As shown by the line drawn at 50% maximum response and occupancy in Fig. 7, the EC50 value of 37 nM and KA value of 84 nM correspond to 30 and 50% A1-adenosine receptor occupancy, respectively. Note that the response curve at values <50% of maximum lies just to the left of the receptor occupancy curve, which suggests little physiological reserve or amplification. More specifically, the ratio of [CPA]occupancy to [CPA]response denotes the physiological reserve (efficiency of receptor occupancy-response coupling) for each given percent maximum response and occupancy (%maximum). For example, the reserve at 50% maximal response and occupancy is termed the pharmacological shift ratio (i.e., KA/EC50), and for this study the ratio is 2.3 (or 84 nM/37 nM). In this manner, the amplification or reserve of the A1-adenosine receptor coupling process (receptor occupancy-to-dromotropic response) can be calculated.

Fig. 7.

Dependence of A1-adenosine receptor occupancy and dromotropic response on the concentration of CPA. %Maximal S-H response and %A1-adenosine receptor occupancy are plotted as a function of concentration of CPA. Experimental control ΔS-H interval data from Fig. 5 were transformed to provide %maximal response data. Likewise, %occupancy data were calculated according to the law of mass action (Eq. 6 in APPENDIX). Horizontal line drawn at 50% maximum level intersects 1) response curve at EC50, level (37 nM) and 2) occupancy curve at KA value (84 nM). This line identifies pharmacological shift ratio for CPA ([CPA]occupancy/[CPA]response), which is 2.3. This ratio at a given %maximum also defines physiological amplification or reserve.

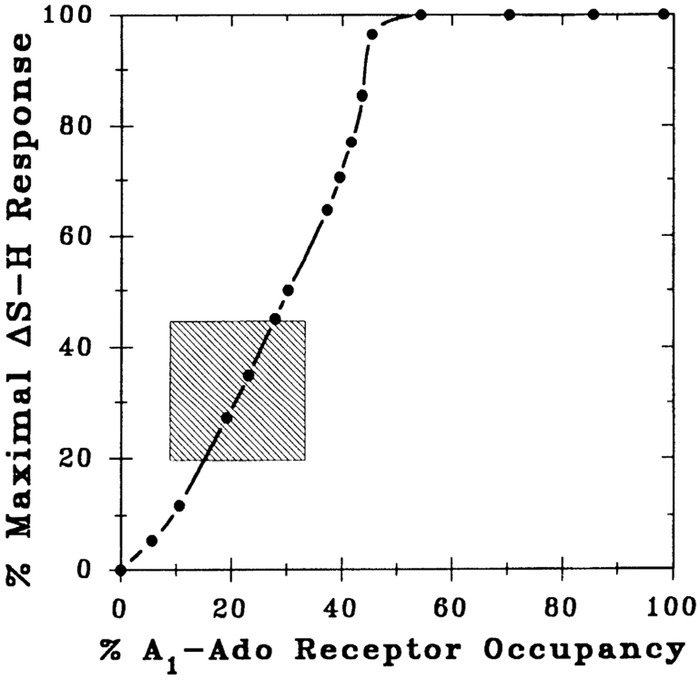

Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between percent A1-adenosine receptor occupancy (abscissa) and percent maximal ΔS-H response (ordinate) induced by CPA. The plot shown in Fig. 8 was derived from data depicted in Fig. 7. Note that at lower percent maximal responses (e.g., <50%), the relationship is almost linear, suggesting poor receptor occupancy-response coupling, and the maximal response was achieved at 46% A1-adenosine receptor occupancy. Consequently, 54% of the receptors can be considered “spare” at the maximal dromotropic response (ΔS-Hmax). Similarly, at the EC50 level, 30% of the AV nodal A1-adenosine receptors are occupied, and hence 20% (i.e., 50%–30%) are spare receptors.

Fig. 8.

A1-adenosine (Ado) receptor occupancy-response curve. Data points were derived from those depicted in Fig. 7. At a given concentration of CPA, %maximal response was plotted against estimated receptor occupancy. This procedure was repeated over a CPA concentration range of 1–75 nM. Shaded area of plot corresponds to experimental data shown in Fig. 5 (i.e., ΔS-H interval from 10 to 22.5 ms or 20 to 44% maximal response levels) used in analysis. At lower %maximal responses (i.e., <50%), relationship is almost linear, indicating poor receptor occupancy-response coupling. Note EC50 and maximal response (i.e., 2° AV block) were achieved at 30 and 46% A1-adenosine recentor occupancy, respectively.

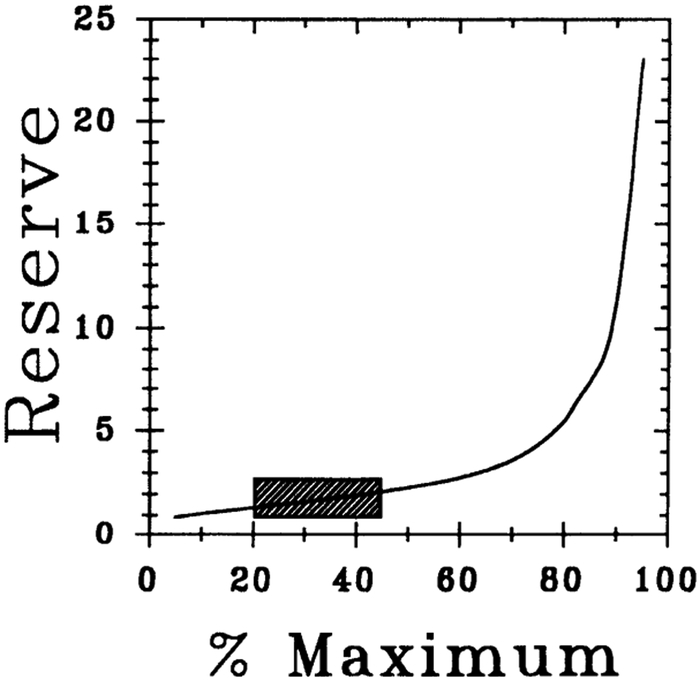

Physiological Reserve

Figure 9 shows the relationship between physiological reserve (Reserve) vs. % maximum occupancy and response (%maximum). The reserve varied from 1 to 2.3 within 0–50% of maximal response range, suggesting a poorly coupled response. The shaded areas in Figs. 8 and 9 correspond to the experimental data in Fig. 5 (i.e., ΔS-H interval values ranging between 10 and 22.5 ms) used in Furchgott’s method of irreversible receptor inactivation.

Fig. 9.

Physiological reserve for CPA-induced negative dromotropic effect in guinea pig heart. Relationship shown between physiological reserve (Reserve) vs. %maximal occupancy and response (%maximum) and was constructed as described in RESULTS. Shaded area corresponds to experimental data shown in Fig. 5 (i.e., ΔS-H interval from 10 to 22.5 ms or 20 to 44% maximal response levels) used in analysis.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used m-DITC-XAC, an irreversible adenosine receptor antagonist, to investigate the A1-adenosine receptor occupancy-response coupling process in the guinea pig AV node. Mathematical analysis of the experimental data based on Furchgott’s method suggest that 1) the degree of physiological amplification (reserve) between A1-adenosine receptor occupancy and dromotropic response is minimal (i.e., a “tightly” coupled process), and 2) a relatively low number of spare A1-adenosine receptors exist in the guinea pig AV node. The above conclusions rely on the validity of the underlying concepts of Furchgott’s method (e.g., law of mass action in occupation theory), which in turn require an irreversible receptor antagonist. Thus it was necessary to demonstrate that 1) m-DITC-XAC antagonizes the effects of adenosine on the AV node, and 2) this antagonism is specific and irreversible. In addition, the KA for CPA was estimated by analyzing its concentration-response relationships in the absence and presence of m-DITC-XAC.

Effects of m-DITC-XAC and Other Alkylxanthines

The xanthine derivatives, DPCPX, CPT, XAC, and m-DITC-XAC dose dependently antagonized the negative dromotropic effect of adenosine (Fig. 1). These alkylxanthines produced monophasic concentration-response displacement curves with apparent Hill coefficients (slope values) approximating one, which implies antagonism at a common receptor, and a 1:1 agonist-antagonist stoichiometric interaction with this receptor. Estimated IC50 values of the adenosine antagonists based on analysis of the concentration-response relationships using a nonlinear weighted (variance−1) algorithm (23) revealed that CPT, XAC, and m-DITC-XAC are 4-, 34-, and 345-fold less potent than DPCPX, respectively. Thus the rank order of potency is DPCPX > CPT > XAC > m-DITC-XAC. The potency of m-DITC-XAC in physiological mediums (i.e., IC50 value of 414 ± 151 nM for the attenuation of an adenosine-induced 15 ms S-H interval prolongation) is markedly less than the 1.2 nM (Ki) obtained in rat brain membrane preparations (13). This variation may be due to differences in species, tissue type, and/or changes in m-DITC-XAC’s activity in physiological (aqueous) mediums. Regardless of the mechanism for this difference in binding and functional results, it is not the change in activity that is important to the present analysis but rather the irreversibility of m-DITC-XAC’s effect that is crucial for the valid application of Furchgott’s method (i.e., to estimate KA). Therefore, evidence of the irreversibility of m-DITC-XAC’s functional antagonism of the negative dromotropic effect of adenosine was obtained by three different means. That is, the evidence is derived from experiments that demonstrated 1) submaximal responses to adenosine after treatment with m-DITC-XAC, i.e., 5 min of 1.0 μM m-DITC-XAC pretreatment prevented the negative dromotropic effect of a 20 μM concentration of adenosine (Fig. 2C); 2) near complete antagonism of adenosine’s AV nodal effects after 60 min of washout of m-DITC-XAC (Fig. 4A); and 3) a marked time- and concentration-dependent onset of action for m-DITC-XAC-induced antagonism of the negative dromotropic effect of adenosine (Fig. 4B).

In addition, m-DITC-XAC appeared to specifically antagonize the negative dromotropic response of adenosine (Fig. 3). This conclusion was based on the observation that m-DITC-XAC neither attenuated a carbachol-induced S-H interval prolongation (Fig. 3B) nor affected the baseline S-H interval (Fig. 3C). Thus the acylation produced by m-DITC-XAC (13) appears to preferentially inactivate the A1-adenosine receptor system.

Estimation of KA for CPA

In this study we used an irreversible adenosine receptor antagonist (e.g., m-DITC-XAC) to estimate the A1-adenosine receptor KA value for the effect of CPA in intact functioning AV nodal tissue (i.e., negative dromotropic action). In an attempt to characterize the A1-adenosine receptor system, previous investigators have correlated functional to binding data in brain membranes (32), adipocytes (22), and myocardium (21, 24, 33). However, because no irreversible adenosine receptor antagonists were available until recently (4, 13), previous studies had to rely exclusively on analyses of radioligand binding data to obtain estimates of KA for A1-adenosine receptor agonists. However, several important pitfalls may confound interpretation of estimated KA values from binding studies (11, 20, 31). For instance, nonphysiological changes in ionic composition (divalent cations or Na+), guanine nucleotide content, or the method of membrane preparation (receptor solubilization) are known to influence the estimate of KA. The direct assessment of the KA value for CPA in normoxic intact hearts using Furchgott’s method (9) of analysis of irreversible receptor inactivation is an alternative approach to estimate the KA value and may avoid some of the above-mentioned difficulties with radioligand binding studies. Furthermore, in the present study, the correlation of functional with radioligand binding data would have been very difficult given the limited amount of guinea pig AV nodal tissue available for radioligand binding techniques.

The linearized equation form (Eq. 5 in APPENDIX) has been the most commonly used approach to determine the fraction (q) of functional receptors remaining after irreversible antagonist treatment and the KA (9, 17). However, sound statistical reasons exist for not making the linear transformation (17) but rather by directly employing a nonlinear regression technique to the untransformed equation (Eq. 4 in APPENDIX). Nevertheless, for comparative purposes the concentration-response data depicted in Fig. 5 were analyzed using both methods. The nonlinear curve fitting of the untransformed data gave a q and KA value of 0.29 and 84 nM (Fig. 6A), respectively, whereas the linear transformation gave a q and KA of 0.28 and 78 nM (Fig. 6B), respectively. Thus, regardless of the method of analyses, the q and KA values were similar. In addition, both methods of analysis resulted in an excellent goodness of fit. For instance, the sum of squares (SOS) difference for the nonlinear analysis was only 0.36 nM2. The minimal SOS difference for the nonlinear analysis implies that the underlying assumptions of Furchgott’s method appears to be valid (e.g., law of mass action in occupation theory).

Physiological Amplification of AV Nodal A1-Adenosine Receptor Coupling Process

As shown in Fig. 7, the concentration-response curve for CPA lies to the left of the A1-adenosine receptor occupancy curve, which suggests that physiological amplification is present. A measure of physiological reserve or amplification is the pharmacological shift ratio, which is defined by KD/EC50. For example, the muscarinic cholinergic system in guinea pig ileum possessed a pharmacological shift ratio equal to 398 and 38 for acetylcholine- (26) and carbachol- (10) induced contractile responses, respectively. Similarly, in the α-adrenoreceptor system, Barber (1) found a pharmacological shift ratio of 200 for adenylyl cyclase activation in epinephrine-stimulated S49 lymphoma cells. In contrast, our investigation revealed a pharmacological shift ratio of only 2.3 for CPA’s negative dromotropic response. Thus when compared with other receptor-effector systems, the degree of amplification between A1-adenosine receptor occupancy and dromotropic response is relatively minimal (i.e., a “tightly” coupled process).

As indicated above, the shaded areas in Figs. 8 and 9 correspond to experimental data directly used in Furchgott’s method (horizontal bars in Fig. 5). In this range of response, the receptor occupancy as a function of agonist (CPA) concentration appears to reliably conform with the law of mass action (Eq. 6 in APPENDIX). However, because of the unusual shape of adenosine’s negative dromotropic concentration-response curve, the analysis of physiological reserve is more appropriate at data points less than the EC50 values. More specifically, when compared with a classical log concentration-response relationship, the adenosine concentration-response curve (Fig. 2) has 1) a parabolic rather than the usual sigmoidal shape, 2) an abrupt endpoint as a maximal response (e.g., AV block), and 3) an accelerated rate of response as higher agonist concentrations are achieved. The net result is a nonparallel shift between A1adenosine receptor occupancy and dromotropic response curves (Fig. 7).

As shown in Fig. 9, at low percent maximal dromotropic response levels (i.e., 10–15%), the KD/EC50 was approximately 1, indicating a 1:1 receptor occupancy-response coupling (i.e., no physiological reserve). The KD/EC50 increased to ~2.3 at higher levels of maximal response (i.e., 45–50%), indicating “less tight” coupling, a value that is still relatively small compared with other systems (1, 10, 26). Figure 8 illustrates that another indication of the tight coupling between A1-adenosine receptor occupancy and dromotropic response is given by the approximately linear relationship between receptor occupancy-response (i.e., low efficiency of receptor occupancy-response coupling) at response values <50% of maximum. Tissues possessing an efficient stimulus-response coupling mechanism have a hyperbolic-shaped receptor occupancy vs. percent maximal response relationship, which indicate maximal responses at low receptor occupancy levels (16, 17). For example, ~3 and 12% of α-adrenergic receptors are required to be occupied in order for isoproterenol to elicit a maximal response in rat. and guinea pig atria, respectively (17, 18). In contrast, the maximal CPA-induced negative dromotropic response required 46% A1-adenosine receptor occupancy (i.e., a relatively poorly coupled process).

Spare AV Nodal A1-Adenosine Receptors

Drugs may produce maximal responses at submaximal receptor occupancy. Indeed, many tissue responses to potent agonists occur in the 5–15% receptor occupancy range (18), and the tissue would have 85–95% spare receptors (or receptor reserve). Thus, given the potency of CPA, the A1-adenosine receptor-mediated response appears to have a comparatively low number of spare receptors. Taking into consideration that “spare receptors” is an agonist and tissue specific entity (similar to physiological reserve or amplification), if a highly potent and selective A1-adenosine receptor agonist such as CPA is poorly coupled, it is predictable that less potent adenosine analogues (including adenosine itself) would have considerably fewer spare receptors and a lower degree of physiological reserve. However, the adenosine concentration-response relationship in hearts pretreated with 0.2 μM m-DITC-XAC (Fig. 2C) is consistent with the presence of spare receptors for the natural ligand. The rightward shift of the adenosine concentration-response curve in the presence of m-DITC-XAC and the observation that adenosine can still produce a maximal response is consistent with the existence of an AV nodal A1-adenosine receptor reserve. This interpretation is in accordance with the classical theory of spare receptors. That is, if only a small fraction of receptors is irreversibly inhibited by an antagonist, then an initial rightward agonist concentration-response shift occurs. However, if a greater fraction of receptors is inactivated (0.5 μM m-DITC-XAC, Fig. 2C), then a reduction in maximal response will also be seen (9).

Although the term spare receptors was originally meant to be used at maximal responses, more recently, its usage has been broadened to include submaximal responses as well (16, 17). For example, studies by Lohse et al. (22) using irreversible agonist photoaffinity labeling and adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) determinations in isolated rat adipocytes revealed >40% spare A1-adenosine receptors at the IC50 level, and a pharmacological shift ratio of 20. In the present investigation, we also demonstrated spare A1adenosine receptors at the EC50 level in the guinea pig AV node, but fewer in number (i.e., 20% spare). However, as Kenakin (16, 17) points out, use of the term “spare receptors” at submaximal levels is a misnomer and is probably best avoided. This terminology erroneously implies that a separation between binding (occupancy) and response (e.g., EC50 < KA; Fig. 7) is solely attributable to receptor number. In reality, other important mechanisms (e.g., efficiency of receptor coupling) may also contribute to the observed binding-response separation (16, 17). For example, Stickle and Barber (29) concluded that epinephrine binding frequency among β-adrenergic receptors and the mobility of β-adrenoceptors and/or GTP-binding protein contribute to a binding-response separation in S49 lymphoma cells. Consequently, we report “20% spare A1-adenosine receptors at the EC50 level” only to compare this value with that reported in a previous study (22). In the current study, the term physiological reserve is used to characterize the receptor occupancy-response coupling efficiency (amplification) at submaximal dromotropic response levels.

Our finding of limited physiological reserve is consistent with the interpretation of studies by Tawfik-Schlieper et al. (33) in guinea pig atrial myocytes using 86Rb+ efflux measurements, Martens et al. (24) in rat ventricular myocytes using cAMP determinations, and Stroher et al. (32) in guinea pig cortical membranes using cAMP levels. These results reinforce the concept that physiological reserve (or amplification) and spare receptors are agonist-, receptor- (A1-adenosine vs. β-adrenergic), species-, organ- and perhaps within-an-organ- (AV nodal tissue versus ventricular myocyte) dependent entities.

In summary, the experimental results obtained using m-DITC-XAC are consistent with a specific and irreversible antagonism of the negative dromotropic effects of adenosine and CPA. Evidence suggests that the guinea pig AV node possesses a relatively small number of spare A1-adenosine receptors, and the A1-adenosine receptor occupancy-response mechanism is a “tightly” coupled process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Steve Baker for reviewing this manuscript.

D. Dennis is a recipient of the Clinician-Scientist Award 90CS/9, Florida Affiliate of the American Heart Association.

This work was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-35272 and by the Suncoast Chapter of the American Heart Association.

APPENDIX

| (1) |

where ΔS-H is S-H interval prolongation (ms); ΔS-Hmax is extrapolated maximal S-H interval prolongation (ms); n is the apparent Hill coefficient, or steepness factor (slope); IC50 is concentration of Ado antagonist attenuating 50% of Ado-induced S-H prolongation (nM); and [Ado] is concentration of Ado antagonist (nM)

| (2) |

where [CPA] is concentration of N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA) (nM) and a, b, and c are curve-fitting parameters

| (3) |

where EC50 is concentration of CPA producing 50% maximal S-H interval response (nM)

| (4) |

where A is the equieffective concentration of CPA in control hearts (nM); A′ is equieffective concentration of CPA in hearts treated with m-DITC-XAC (nM); q is the fraction of viable A1-Ado receptors remaining after treatment with m-DITC-XAC; and KA is the agonist equilibrium dissociation constant of CPA (nM)

| (5) |

| (6) |

where ρ is the fractional occupancy of total A1-Ado receptors; and [A] is the concentration of CPA (nM).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barber R Discrimination between intact cell desensitization and agonist affinity changes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 46: 263–270, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belardinelli L, Fenton AR, West GA, Linden J, Althaus JS, and Berne RM. Extracellular action of adenosine and the antagonism by aminophylline on the atrioventricular conduction of isolated perfused guinea pig and rat hearts. Circ. Res 51: 569–579, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belardinelli L, Linden J, and Berne RM. The cardiac effects of adenosine. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis 32: 73–97, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boring D, Xiao-Duo J, Zimmet J, Taylor K, Stiles GL, and Jacobson KA. Trifunctional agents as a design strategy for tailoring ligand properties: irreversible inhibitors of A1 adenosine receptors. Bioconj. Chem 2: 77–88, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruns RF, Daly JW, and Snyder SH. Adenosine receptors in brain membranes: binding of N6-cyclohexyl[3H]adenosine and 1,3′-diethyl-8-[3H]phenylxanthine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77: 5547–5551, 1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruns RF, Daly JW, and Snyder SH Adenosine receptor binding: structure-activity analysis generates extremely potent xanthine antagonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80: 2077–2080, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemo HF, and Belardinelli L. Effect of adenosine on atrioventricular conduction. I. Site and characterization of adenosine action in the guinea pig atrioventricular node. Circ. Res 59: 427–436, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly JW Adenosine receptors: targets for future drugs. J. Med. Chem 25: 197–207, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furchgott RF The use of β-haloalkylamines in the differentiation of receptors and in the determination of dissociation constants of receptor-agonist complexes. Adv. Drug Res 3: 21–56, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furchgott RF Pharmacological characterization of receptors: its relation to radioligand binding studies. Federation Proc. 37: 115–120, 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman RR, Cooper MJ, Gavish M, and Snyder H. Guanine nucleotide and cation regulation of the binding of [3H] cyclohexyladenosine and [3H]dithylphenylxanthine to adenosine A1 receptors in brain membranes. Mol. Pharmacol 21: 329–335, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton HW, Ortwine DF, Worth DF, Badger EW, Bristol JA, Bruns RF, Haleen SJ, and Steffen RP. Synthesis of xanthines as adenosine antagonists: a practical quantitative structure-activity relationship application. J. Med. Chem 28: 1071–1079, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson KA, Barone S, Kammula U, and Stiles G. Electrophilic derivatives of purines as irreversible inhibitors of A1 adenosine receptors. J. Med. Chem 32: 1043–1051, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins J, and Belardinelli L. Atrioventricular nodal accommodation in isolated guinea pig hearts: physiologic significance and role of adenosine. Circ. Res 63: 97–116, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenakin TP The classification of drugs and drug receptors in isolated tissues. Pharmacol. Rev 36: 165–222, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kenakin TP Receptor reserve as a tissue misnomer. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 7: 93–95, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kenakin TP Drug-receptor theory In: Pharmacologic Analysis of Drug-Receptor Interactions. New York: Raven, 1987, p. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenakin TP, and Beek D. Is prenalterol (H133/80) really a selective beta-1 adrenoceptor agonist? Tissue selectivity resulting from differences in stimulus-response relationships. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 213: 406–412, 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koek W, Head R, Holsztynska EJ, Woods JH, Domino EF, Jacobson AE, Rafferty ME, Rice KC, and Lessor RA. Effects of metaphit, a proposed phencyclidine receptor acylator, on catalepsy in pigeons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 234: 648–653, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung E, and Green RD. Density gradient profiles of A1 adenosine receptors labeled by agonist and antagonist radioligands before and after detergent solubilization. Mol. Pharmacol 36: 412–419, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang B Characterization of the adenosine receptor in cultured embryonic chick atrial myocytes: coupling to modulation of contractility and adenylate cyclase activity and identification by direct radioligand binding. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 249: 775–784, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lohse MJ, Klotz K-N, and Schwabe U. Agonist photoaffinity labeling of A1 adenosine receptors: persistent activation reveals spare receptors. Mol. Pharmacol 30: 403–409, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marquardt DW An algorithm for least-squares estimation of non-linear parameters. J. Soc. Indust. Appl. Math 2: 431–441, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martens D, Lohse MJ, and Schwabe U. [3H]-8-Cyclopen-tyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine binding to A1 adenosine receptors of intact rat ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res 63: 613–620, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olsson RA, and Pearson JD. Cardiovascular purinoceptors. Physiol. Rev 70: 761–845, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sastry R, and Cheng HC. Dissociation constants of d- and l-lactoylcholines and related compounds at cholinergic receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 180: 326–339, 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schild HO pA2, a new scale for the measurement of drug antagonism. Br. J. Pharmacol 2: 189–206, 1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sershen H, Berger P, Jacobson AE, Rice KC, and Reith MEA. Metaphit prevents locomotor activation induced by various psychostimulants and interferes with the dopaminergic system in mice. Neuropharmacology 27: 23–30, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stickle D, and Barber R. Evidence for the role of epinephrine binding frequency in activation of adenylate cyclase. Mol. Pharmacol 36: 437–445, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stiles GL Adenosine receptors: structure, function and regulation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 7: 486–490, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stiles GL A1 adenosine receptor-G protein coupling in bovine brain membranes: effects of guanine nucleotides, salt and solubilization. J. Neurochem 51: 1592–1598, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stroher M, Nanoff C, and Schutz W. Differences in the GTP-regulation of membrane-bound and solubilized A1-adenosine receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol 340: 87–92, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tawfik-Schlieper H, Klotz K-N, Kreye VAW, and Schwabe U. Characterization of the K+-channel-coupled adenosine receptor in guinea pig atria. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol 340: 684–688, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]