Abstract

Purpose:

To compare the acceptance of diabetic retinopathy (DR) screening by the proximity of care and health education in rural Maharashtra.

Methods:

Study was done in the public health facilities in four blocks (in two blocks at community health center (CHC) level and in other two blocks at primary health center (PHC) level with the provision of transport from villages to PHCs) over 3 months. Health education was not imparted in one block in each segment. Health education consisted of imparting knowledge on diabetes mellitus (DM) and DR by trained village-level workers. The screening was done using non-mydriatic fundus camera and teleophthalmology supported remote grading of DR.

Results:

In the study period, 1,472 people with known diabetes were screened in four blocks and 86.6% (n = 1275) gradable images were obtained from them. 9.9% (n = 126) were detected having DR and 1.9% (n = 24) having sight-threatening DR (STDR). More people accepted screening closer to their residence at the PHC than CHC (24.4% vs 11.4%; P < 0.001). Health education improved the screening uptake significantly (14.4% vs 18.7%; P < 0.01) irrespective of the place of screening—at CHC, 9.5% without health education vs 13.1% with health education; at PHC, 20.1% without health education versus 31.6% with health education.

Conclusion:

Conducting DR screening closer to the place of living at PHCs with the provision of transport and health education was more effective for an increase in the uptake of DR screening by people with known diabetes in rural Maharashtra.

Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy, health education, screening, screening location

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) in all age groups worldwide was estimated to be 2.8% in 2000 and 4.4% in 2030.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the number of adults with diabetes in India will increase to 80 million by 2030.[1] The overall worldwide prevalence of any diabetic retinopathy (DR) among people with diabetes is 34.6% with 10.2% of those with diabetes having sight-threatening DR (STDR).[2] In India, the prevalence of DR is around 18% in urban populations and 10.3% in rural populations.[3] Significant risk factors for DR are the duration of diabetes and poorly controlled hyperglycemia and hypertension.[4] Over the last two decades, DR has emerged as a common cause of ocular morbidity and blindness in India.[5] However, diagnostic and treatment facilities in India are mostly limited to urban tertiary care centers.[6] Many people with diabetes are unaware of their disease and a third of people with diabetes never undergo eye examination[7,8] The Indian National Program for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCB and VI) recommends opportunistic screening for identification of DR which is integrated into the health system at all levels.[9] The uptake of DR screening is poor due to the lack of knowledge about the seriousness of the disease and its complications.[10]

Low levels of health literacy, which is “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions”[11] is an important barrier to accessing screening by people with DM in India and other developing countries.[12,13,14,15] It is not unusual to detect STDR in people with diabetes at their first eye examination.[13,16,17,18,19] Hence, early screening is required before symptoms develop. The advantage of engaging village health workers (VHWs) as health educators in DR screening has been demonstrated in a few studies in India.[20,21] Patient awareness and health education, similarly, play a vital role.[22] Two questions were addressed in the current study: (1) does health education improve the uptake of DR screening? (2) Does proximity to where screening takes place (location), that is, community health center (CHC) or primary health center (PHC) impact the uptake of DR screening?

The study was embedded within a pilot project of DR screening undertaken by Kasturba Hospital, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sewagram, Wardha, which was integrated into noncommunicable diseases (NCD) clinics in one district hospital and four CHCs, with outreach screening in 22 PHCs affiliated to the CHCs, in five blocks in Wardha district in Maharashtra state. In all the blocks, the details of the number of people with diabetes attending the facility were obtained from the NCD register. In brief, for screening in NCD clinics in CHCs, paramedical ophthalmic assistants (PMOA) were trained in measuring visual acuity using the early treatment diabetic retinopathy study (ETDRS) charts and image capture using a non-mydriatic fundus camera (Forus 3-Nethra, Bangalore, India). Images were graded remotely by ophthalmology experts. NCD clinics in CHCs were operational daily but DR screening was scheduled once or twice a week based on the availability of PMOAs. Other staff were was oriented on diabetes and DR including physicians, PMOAs, nurses and other paramedics. An online system was used to document the uptake of screening. Screening for DR in PHCs affiliated with the CHCs (3–5 per CHC) entailed weekly visits by the mobile team from the base hospital that screened using the same imaging system.

Methods

This interventional study was embedded in the program outlined above and was carried out over 3 months in four blocks (in two blocks at CHCs level and in other two blocks at PHCs level with the provision of transport from village to PHCs), in Wardha district. In each group of blocks, one was randomly selected for the health education intervention. The population is predominantly rural. The blocks were grouped as facilities A and B: screening for DR in CHCs. Health education was not imparted in A but was imparted in B. Facilities C and D: screening in PHCs. Health education was not imparted in C block but was imparted in D. The health education intervention in the two settings was delivered by Village Level Health Workers (VHWs). VHWs, including accredited social health activist (ASHA) (115 in block B; 102 in block D) were trained who in turn provided health education to people with diabetes in their villages using written information (posters and leaflets) in the local languages (Marathi, Hindi) which explained DM and DR. Literacy rate is 82.9% for women and 86.9% for men in Wardha district. VHWs have list of diabetic patients in their villages and health education focused on people with diabetes and their care providers was provided. Posters were used to give oral explanations and leaflets were handed over giving the date and place of screening. ASHA workers and VHWs mobilized people with diabetes in the community to attend for screening, who were transported to the PHC for screening and back to their village afterward.

| Facility A | Facility B | |

|---|---|---|

| Screening in CHC | No health education No transport | Health education by VHW No transport |

| Facility C | Facility D | |

| Screening in PHC | No health education Transport to and from village | Health education by VHW Transport to and from village |

The following procedures were performed in all four blocks. Demographic details linked to their unique identification (UID) (Aadhar number) of all people with diabetes undergoing screening were entered in tablets using DRROP software. Presenting visual acuity was measured using an ETDRS chart at 4 m under standard lighting conditions. Refraction was performed and spectacles prescribed where required. Blindness and visual impairment were classified as per the WHO International Classification of Diseases 11 (2018).[23] Single-field fundus photograph,[24] one for each eye capturing disc and macula, was taken by PMOAs, supervised by the ophthalmology residents from the base hospital during the study period. Images were uploaded on cloud and remotely graded by trained ophthalmologists at the base hospital. Using teleophthalmology software, the report was shared with the people after screening. Medical social workers counseled patients in the facility about the need for repeat annual screening or where to go if referred for further management. The following patients were referred to the base hospital for further investigations and appropriate management: those with DR in one or both eyes or ungradable images or patients with best-corrected visual acuity <6/60 in either eye.

DR was graded using the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema disease severity scales.[25] Any grade worse than moderate nonproliferative DR (NPDR) or diabetic macular edema (DME) in one or both eyes was classified as STDR.

The outcomes of the study were:

Primary outcome: uptake of DR screening at facilities with and without health education

Another outcome: uptake of screening by type of facility.

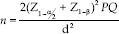

Sample size calculation

The outcome for the sample size calculation was the uptake of screening at facilities with and without health education. Since there were four groups in the study, the sample size, which used the comparison of two proportions, was adjusted for multiple comparisons. Assumptions on the uptake used the minimum anticipated to ensure a large enough sample size.

Sample size formula for comparison of two proportions—

Where,

Q = 1–P

d = p2–p1

p1 Proportion of compliance in one group = 0.10 (10%)

p2 Proportion of compliance in another group = 0.20 (20%)

Z1–α/2 = 2.64 at 5% level of significance after adjusting for multiple comparisons

Z1–β = 0.84 at 80% power

d Clinical significance difference (p1–p2) = 0.10 (10%)

n Sample size required in each group

The minimum sample size required was 309 people with diabetes in each group. To account for clustering in this trial, a design effect of two was used, increasing the size of the sample to be included in each facility to 618.

Analysis

For statistical analysis significance of both interventions was analyzed separately by the z test.

Ethics

The study was undertaken after approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sewagram Wardha. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each person before the examination and/or screening.

Results

The number of people registered with diabetes in the NCD clinics in all four blocks varied, ranging from 1,298 in one of the blocks at PHCs screening to 2,524 in one of the blocks with CHC screening [Table 1]. The number of people screened in both blocks with PHCs screening was similar (433 and 411) and higher than in the blocks with CHC screening (239 and 389). A total of 1,472 people with diabetes out of 8,954 registered (16.4%) were screened for DR in the four blocks over the 3-month period [Table 1]. The mean age of those screened was 57.9 ± 12 years and 53.8% were male [Table 2]. Characteristics of patients screened in each of the four blocks were not significantly different with respect to gender, age, duration of diabetes, and visual acuity.

Table 1a.

Uptake of screening for diabetic retinopathy by health education status and location of screening

| Group/Block | Intervention | DM patients enrolled in NCD register | Screened for DR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening location | Health education | n | % (95% CI) | ||

| A | CHC | No | 2524 | 239 | 9.5% (8.4-10.7) |

| B | CHC | Yes | 2973 | 389 | 13.1% (11.9-14.3) |

| C | PHC | No | 2159 | 433 | 20.1% (18.4-21.8) |

| D | PHC | Yes | 1298 | 411 | 31.7% (29.2-34.2) |

| Total | 8954 | 1472 | 16.4% (15.7-17.2) | ||

CHC=community health center; PHC=primary health center, DM=diabetes mellitus, DR=diabetic retinopathy, NCD=noncommunicable disease

Table 2.

Age and duration of diabetes in people screened for DR, by location of screening

| Group A (CHC) | Group B (CHC) | Group C (PHC) | Group D (PHC) | PHCs | CHCs | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screened for DR | 239 | 389 | 433 | 411 | 844 | 628 | 1472 |

| Male | 127 (53.1) | 220 (56.5) | 229 (52.9) | 217 (52.8) | 446 (52.8) | 347 (55.3) | 793 (53.8) |

| Female | 112 (46.9) | 169 (43.5) | 204 (47.1) | 194 (47.2) | 398 (47.1) | 281 (44.7) | 679 (46.2) |

| Age in Years (Mean±SD) | 58.4+12.3 | 58.6±11.8 | 57.4±12.2 | 58.1±11.9 | 58.2±12.3 | 57.7±11.8 | 57.9±12.0 |

| No health education | 58.4+12.3 | NA | 57.4±12.2 | NA | 57.4±12.2 | 58.4+12.3 | 57.7+11.8 |

| Health education | NA | 58.6±11.8 | NA | 58.1±11.9 | 58.1±11.9 | 58.6±11.8 | 58.3+11.8 |

| Duration of DM (±SD), yrs | 4.81±4.81 | 4.25±4.2 | 4.43±4.4 | 4.56±4.4 | 4.49±4.4 | 4.46±4.4 | 4.51±4.5 |

| No health education | 4.81±4.81 | NA | 4.43±4.38 | NA | 4.43±4.4 | 4.81±4.8 | 4.5+4.6 |

| Health education | NA | 4.2±4.2 | NA | 4.56±4.4 | 4.56±4.4 | 4.25±4.2 | 4.4+4.3 |

The uptake of screening varied by facility [Table 1a and b]; the highest uptake was in the block with PHC level screening with health education and provision of transport to PHCs from villages (31.7%) while the lowest was in the block with CHC level screening without health education (9.5%). The uptake was significantly higher in the facilities with health education than in those without (18.7% and 14.3%, respectively, P < 0.01), and was significantly higher in blocks with PHCs level screening with provision of transport to PHCs from villages than CHCs level screening (24.4% and 11.4%, respectively, P = <0.001).

Table 1b.

Uptake of screening for diabetic retinopathy by health education status and location of screening

| Intervention | Group | DM patients enrolled in NCD register | Proportion Screened for DR | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % ( 95% CI ) | ||||

| Screening location | |||||

| CHC | A+B | 5497 | 628 | 11.4% (10.6-12.3) | Z test=15.33, P<0.0001 |

| PHC | C+D | 3457 | 844 | 24.4% (23.0-25.9) | |

| Health education | |||||

| NO | A+C | 4683 | 672 | 14.3% (13.4-15.4) | Z test=6.83, P<0.0001 |

| YES | B+D | 4271 | 800 | 18.7% (17.6-19.9) | |

| Total | 8954 | 1472 | 16.4% (15.7-17.2) | ||

CHC=community health center, PHC=primary health center, DM=diabetes mellitus, DR=diabetic retinopathy, NCD=non-communicable disease

A third of those screened (35.4%) had some degree of visual impairment: 7.8% (114) were blind, 6.3% (93) had severe visual impairment, 21.3% (314) had moderate visual impairment, and 64.6% (951) had mild or no visual impairment. There was not much difference in visual status between the people who did or did not receive health education [Table 3].

Table 3.

Visual status of diabetic patients screened by health education

| Vision category | Overall (n) | Health education not imparted | Health education imparted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blind | 7.8% (114) | 7.9% (53) | 7.6% (61) |

| Severe visual impairment | 6.3% (93) | 6.8% (46) | 5.9% (47) |

| Moderate visual impairment | 21.3% (314) | 23.0% (154) | 20.0% (160) |

| Mild or no visual impairment | 64.6% (951) | 62.3% (419) | 66.5% (532) |

| Total | 100% (1472) | 100% (672) | 100% (800) |

Fundus images were gradable in 86.6% (1275/1472) of those screened. In the gradable images, 9.9% (126/1275) had any DR and 1.9% (24/1275) had STDR [Table 4].

Table 4.

Profile of DM patients and prevalence of DR in various groups (blocks)

| Group A no. (%) | Group B no. (%) | Group C no. (%) | Group D no. (%) | Total no. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total registered | 2524 | 2973 | 2159 | 1298 | 8954 |

| Total screened for DR | 239 | 389 | 433 | 411 | 1472 |

| Coverage | 9.5% | 13.1% | 20.1% | 31.7% | 16.4% |

| Gradable images | 208 | 337 | 374 | 356 | 1275 |

| Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy (in gradable images in one or both eyes of person n=1275) | |||||

| Prevalence of DR | 21 (10.1%) | 30 (8.9%) | 29 (7.8%) | 46 (12.9%) | 126 (9.9) |

| Prevalence of DME | 2 (0.9%) | 3 (0.9%) | 2 (0.5%) | 7 (1.9%) | 14 (1.1) |

| Prevalence of STDR | 4 (1.9%) | 6 (1.8%) | 5 (1.3%) | 9 (2.5%) | 24 (1.9) |

| Proportion of STDR in DR patients | 19.1% | 20.0% | 17.2% | 19.5% | 19.1% |

| Visual status of screened patients in blocks | |||||

| Mild or no visual impairment | 142 (59.4) | 249 (64.0) | 277 (63.9) | 283 (68.8) | 951 (64.60) |

| Moderate visual impairment | 60 (25.1) | 82 (21.1) | 94 (21.7) | 78 (18.9) | 314 (21.30) |

| Severe visual impairment | 20 (8.4) | 25 (6.4) | 26 (6.0) | 22 (5.5) | 93 (6.30) |

| Blindness | 17 (7.1) | 33 (8.5) | 36 (8.4) | 28 (6.8) | 114 (7.80) |

DM - Diabetes mellitus; DME - Diabetic macular edema; DR - Diabetic retinopathy; STDR - Sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy

Discussion

DR can lead to potential sight-threatening complications, which can be prevented by regular dilated fundus examination and referral when required.[26] The importance of early diagnosis and screening in diabetes care facilities is recognized.[27] The screening was done with a non-mydriatic fundus camera, proven for quality DR screening.[28,29] Universal coverage is feasible when screening is cost-effective, reaches the target population, and is accepted by the people.[30] A cost-effective DR screening in rural India is possible with the currently used and emerging technology of telemedicine.[31]

Improving patient engagement with preventive services requires persistent effort and innovation from the service providers.[32] In the present study, two different methods were investigated—the proximity of care with transport to and from the facility and health education. Earlier studies have identified the following barriers to good uptake of DR screening; these factors are lack of awareness, accessibility, affordability, poor infrastructure, lack of skilled manpower and outdated technology.[33,34,35,36] Imparting health education, bringing the point of care to nearer PHC, the use of PMOAs in screening, and the use of non-mydriatic cameras addressed these difficulties.

The study showed that the involvement of ASHAs in providing health education to the people with diabetes enhanced DR screening uptake. ASHAs can act as local change agents, role models, and mentors, task sharing helps.[37] Similarly, delivery of care closer to the people is equally important as seen in this study that there was more acceptance for DR screening in the PHC located closer to the residence with the provision of transport from village to PHC than the CHC which was farther from the residence; but this is possible only with adequate increase in both infrastructure and skilled manpower.

A weakness of the study was that the sample size of 2,456 required for detailed analysis was not achieved during study duration, and less than 20% of people registered in the NCD clinic were screened. As the sample size was inadequate for statistical analysis for four individual groups, both interventions were analyzed separately by combining two blocks in each group [Table 1b]. While the study demonstrated that the care given closer to residence and advocacy improves the screening uptake in the short project period of 3 months, the long-term impact of these strategic decisions needs to be evaluated.

The strength of the study lies in the extension of DR screening beyond the NCD clinics. This is technically possible only with increased allocation of material and manpower resources. In the absence of one or both resources, advocacy and community participation are key to success for improving uptake of this important community program.

Conclusion

Conducting DR screening closer to the place of living at PHCs with the provision of transport and health education was more effective, resulting in an increase in the uptake of DR screening by people with known diabetes in rural Maharashtra.

Financial support and sponsorship

The Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust, London, UK.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, Lamoureux EL, Kowalski JW, Bek T, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:556–64. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raman R, Ganesan S, Pal SS, Kulothungan V, Sharma T. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in rural India. Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Study III (SN-DREAMS III), report no 2. BMJ Open Diab Res Care. 2014;2:e000005. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2013-000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DCCT Research Group. The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes. 1995;44:968–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murthy GV, Gupta SK, Bachani D, Jose R, John N. Current estimates of blindness in India. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:257–60. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.056937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert CE, Babu RG, Gudlavalleti AS, Anchala R, Shukla R, Ballabh PH, et al. Eye care infrastructure and human resources for managing diabetic retinopathy in India: The India 11-City 9-State Study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;20(Suppl 1):S3–10. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.179768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Namperumalsamy P, Kim R, Kaliaperumal K, Sekar A, Karthika A, Nirmalan PK. A pilot study on awareness of diabetic retinopathy among non-medical persons in South India. The challenge for eye care programmes in the region. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2004;52:257–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohan D, Raj D, Shanthirani CS, Datta M, Unwin NC, Kapur A, et al. Awareness and knowledge of diabetes in Chennai–the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study [CURES-9] J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:283–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vashist P, Singh S, Gupta N, Saxena R. Role of early screening for diabetic retinopathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: An overview. Indian J Community Med. 2011;36:247–52. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.91324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gudlavalleti VS, Shukla R, Batchu T, Malladi BV, Gilbert C. Public health system integration of avoidable blindness screening and management, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:705–15. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.212167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Academy of Sciences, 2004. [Last accessed on 2019 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK216035/

- 12.Singla A, Sharma T, Kaeley N. Awareness of diabetic patients towards diabetes mellitus: A survey based study. Natl J Community Med. 2017;8:606–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang OS, Tay WT, Tai ES, Wang JJ, Saw SM, Jeganathan VS, et al. Lack of awareness amongst community patients with diabetes and diabetic retinopathy: The Singapore Malay eye study. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2009;38:1048–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu L, Chen L. Awareness of diabetic retinopathy is the key step for early prevention, diagnosis and treatment of this disease in China. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:284–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakkar MM, Haddad MF, Gammoh YS. Awareness of diabetic retinopathy among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Jordan. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017;10:435–41. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S140841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thapa R, Paudyal G, Maharjan N, Bernstein P. Demographics and awareness of diabetic retinopathy among diabetic patients attending the vitreo-retinal service at a tertiary eye care center in Nepal. Nepalese J Ophthalmol. 2012;4:10–6. doi: 10.3126/nepjoph.v4i1.5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foma MA, Saidu Y, Omoleke SA, Jafali J. Awareness of diabetes mellitus among diabetic patients in the Gambia: A strong case for health education and promotion. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muecke JS, Newland HS, Ryan P, Ramsay E, Aung M, Myint S, et al. Awareness of diabetic eye disease among general practitioners and diabetic patients in Yangon, Myanmar. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:265–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Khawaldeh OA, Al-Jaradeen N. Diabetes awareness and diabetes risk reduction behaviors among attendance of primary healthcare centers. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2013;7:172–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatt BR. ASHAs in rural India: The ray of hope for diabetes care. J Soc Health Diabetes. 2014;2:18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rani PK, Raman R, Agarwal S, Paul PG, Uthra S, Margabandhu G, et al. Diabetic retinopathy screening model for rural population: Awareness and screening methodology. Rural Remote Health. 2005;5:350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bharathi N, Kalpana S, Sujatha BL, Nawab A, Kumar H. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in diabetics of rural population belonging to Ramanagara and Chikkaballapura districts of Karnataka. Int J Sci Res Pub. 2015;5:794–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. [Last accessed on 2019 Sep 22]. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/details/blindness-and-visual-impairment .

- 24.Williams GA, Scott IU, Haller JA, Maguire AM, Marcus D, McDonald HR. Single-field fundus photography for diabetic retinopathy screening: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1055–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL, 3rd, Klein RE, Lee PP, Agardh CD, Davis M, et al. Global diabetic retinopathy project group. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1677–82. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fong DS, Aiello L, Gardner TW, King GL, Blankenship G, Cavallerano JD, et al. Retinopathy in Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;27(Suppl 1):S84–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anusuya GS, Ravi R, Gopalakrishnan S, Abiselvi A, Stephen T. Prevalence of undiagnosed and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus among adults in South Chennai. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2018;5:5200–4. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sengupta S, Sindal MD, Besirli CG, Upadhyaya S, Venkatesh R, Niziol LM, et al. Screening for vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy in South India: Comparing portable non-mydriatic and standard fundus cameras and clinical exam. Eye (London) 2018;32:375–83. doi: 10.1038/eye.2017.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. Sensitivity and specificity of non mydriatic digital imaging in screening diabetic retinopathy in Indian eyes. Indian J Ophthalmology. 2014;62:851–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.141039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor CR, Merin LM, Salunga AM, Hepworth JT, Crutcher TD, O'Day DM, et al. Improving diabetic retinopathy screening ratios using telemedicine-based digital retinal imaging technology: The Vine Hill study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:574–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das T, Pappuru RR. Telemedicine in diabetic retinopathy – Access to rural India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64:84–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.178151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis K. Improving patient compliance with diabetic retinopathy screening and treatment. Community Eye Health J. 2015;28:68–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC. Reasons for not seeking eye care among adults aged≥40 years with moderate-to-severe visual impairment--21 States, 2006-2009. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep. 2011;60:610–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chou CF, Sherrod CE, Zhang X, Barker LE, Bullard KM, Crews JE, et al. Barriers to eye care among people aged 40 years and older with diagnosed diabetes, 2006-2010. Diabetes Care. 2013;37:180–8. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joshi SR. Diabetes care in India. Ann Glob Health. 2015;81:830–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khandekar R. Screening and public health strategies for diabetic retinopathy in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:178–84. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.95245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah M, Noor A, Deverell L, Ormsby GM, Harper CA, Keeffe JE. Task sharing in the eye care workforce: Screening, detection, and management of diabetic retinopathy in Pakistan. A case study. In J Health Plan Manage. 2018;33:627–36. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]