Abstract

Purpose:

Diabetes is a public health concern in India and diabetic retinopathy (DR) is an emerging cause of visual impairment and blindness. Approximately 3.35–4.55 million people with diabetes mellitus (PwDM) are at risk of vision-threatening DR (VTDR) in India. More than 2/3 of India's population resides in rural areas where penetration of modern medicine is mostly limited to the government public health system. Despite the increasing magnitude, there is no systematic screening for the complications of diabetes, including DR in the public health system. Therefore, a pilot project was initiated with the major objectives of management of DR at all levels of the government health system, initiating a comprehensive program for the detection of eye complications among PwDM at public health noncommunicable disease (NCD) clinics, augmenting the capacity of physicians, ophthalmologists and health support personnel and empowering carers/PwDM to control the risk of DR through increased awareness and self-management.

Methods:

A national task force (NTF) was constituted to oversee policy formulation and provide strategic direction. 10 districts were identified for implementation across 10 states. Protocols were developed to help implement training and service delivery.

Results:

Overall, 66,455 PwDM were screened and DR was detected in 16.2% (10,765) while VTDR was detected in 7.5%. 10.1% of those initially screened returned for the next annual assessment. There was a 7-fold increase in the number of PwDM screened and a 7.6-fold increase in the number of PwDM treated between 2016 and 2018.

Conclusion:

Services for detecting and managing DR can be successfully integrated into the existing public health system.

Keywords: Diabetes, diabetic retinopathy, health systems, India, integration, visual impairment

In India, 65 million people aged ≥20 years were living with diabetes.[1] The prevalence has increased in all Indian states since 1990.[1] International Diabetes Federation (IDF) suggests that the numbers may be even higher and that India accounts for 16.2% (73 million) of the 451 million people with diabetes mellitus (PwDM) worldwide.[2] The overall age-standardized prevalence of DM in India ranges between 7.3% [95% confidence interval (CI) 7.0–7.4] and 7.9% [95% CI: 7.1–8.6].[1,3] The number of people with DM is projected to increase to 125 million by 2045.[3]

Indian evidence shows that among those aged ≥40 years, the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy (DR) among people with DM varies between 10.3% and 15.4%.[4,5] A meta-analysis of 41 studies from Asia showed that the overall prevalence of DR in Asian Type 2 DM was 28% [95% CI: 24%-33%] and it was highest in India.[6] Extrapolating available evidence from India, assuming that 15–20% of people with DM have any DR and 5–7% have VTDR, 3.35–4.55 million people are at risk of visual loss.[7] This translates to 2,240–3,136 people aged 20 years and above in a district of 1 million.

A three-tiered health care protocol has been institutionalized and public health standards have been established to benchmark the services and facilities from the primary level to the district secondary/tertiary care level in India. With a high prevalence of diabetes in rural areas also being reported, the public health system, which is the main formal health structure available to the rural population, needs to be geared up to face the challenge of both DM and DR. Despite the rapidly increasing magnitude of diabetes, there is no systematic screening for the complications of diabetes, including DR in the public health system. A retinal examination is opportunistic when people with DM visit an eye facility. In a recent 11-city study in India, it was observed that almost half (45%) of people with DM presented to an eye clinic only after vision loss had occurred.[8]

Global evidence outlines the need for strategies to tackle the modifiable causes of DR such as control of hyperglycemia and hypertension, and for early detection of diabetes so that management of diabetes and its complications can be more effective. With this background and funding from an international NGO, a projective pilot was initiated to promote screening and effective management of DR in India.

Methods

Population demographics of 2018 show that 66% of India's population resides in rural India.[9] This segment of the Indian population has an increasing prevalence of diabetes, and the public health system is the only source of health care for modern medicine in this population. Therefore, a conscious effort was made to address the needs of this population.

A project grant was received from an international funding organization after a proposal was submitted based on the findings of a situational analysis of diabetes care in India.[10] The overall goal of this funding organization was to develop models of care to reduce avoidable blindness from DR by integrating services into the public health system at every level in a way that is scalable and sustainable.

Major objectives included the management of DR to be included at all levels of the government health system, initiating a comprehensive program for detection of eye complications among the people with DM in public health noncommunicable disease (NCD) clinics, augmenting capacity of physicians through a certificate course, ophthalmologists and health support personnel and empowering carers, and people with DM to reduce the risk of DR through increased awareness and self-management. The latter entailed the establishment of peer support groups and a HelpLine.

A national task force (NTF) was constituted by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India to oversee policy formulation and provide strategic direction. It recommended that the two existing vertical health programs in India—the National Program for Prevention and Control of Cardiovascular Diseases, Cancers, Diabetes, and Stroke (NPCDCS) and the National Program for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCB and VI) be leveraged to identify the areas of synergy at the district and sub-district level. This was important because the NPCDCS facilitates the detection and care of people with DM while the NPCB and VI infrastructure and human resources are stationed at the level of the community health centers (CHC) for screening, and at higher levels for diagnosis and management of DR. The cornerstone of the pilot was that integration of DR screening into the NCD clinics in districts where NPCDCS was functional.

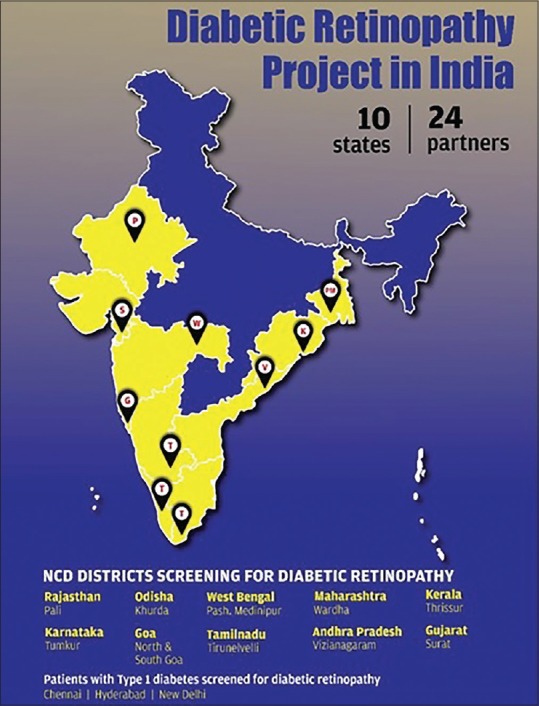

The NTF identified the districts where a pilot project could be rolled out and stated that the integration of DR screening is embedded in the NCD clinics [Figure 1]. The rationale was that DR screening in physicians' clinics would increase uptake of retinal screening and that the management of diabetes and the risk factors for DR can only be managed effectively by physicians.

Figure 1.

States and districts covered in the integrated diabetic retinopathy (DR) pilot project. Source: Original

The implementation started at different times in different states due to the time taken for obtaining respective state government approvals. Mentoring partners to hand-hold the district health system were identified and included both eye care and diabetic care, partners. The NTF met periodically to review the progress of the pilot. Each mentoring partner was then supported to draw up a detailed project implementation plan which was approved by the NTF. The NTF recommended that efforts should be made to trial different models of DR screening so that the best modalities for delivery could be identified. State and district coordination committees were set up in each state to monitor the progress of the rollout.

A theory of change matrix was developed and progress was monitored using a customized log frame. The critical indicators were 75% of known people DM in the pilot districts are aware of the risk of visual impairment from DR, 50% increase in the number of people with DM attending for screening for DR compared to the first year, 50% of the known people with DM return for a repeat annual DR screening and a 40% reduction in the proportion of visual loss among known people with DM.

The NTF suggested that core cross-cutting themes such as advocacy, communication, web portal, guidelines, operational research, and dissemination should be led by technical expert groups established for the purpose while district implementation would be the responsibility of the mentoring partners. Both aspects would be supported by the program grant management team at the Indian Institute of Public Health Hyderabad, Public Health Foundation of India (IIPHH-PHFI).

Results

The first integrated models were rolled out from March 2016 onwards [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of the project sites and implementing partners in the pilot initiative

| State | District | Year | Implementing partner | Mentoring partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | Vizianagaram | Mar 2016 | Health Department, AP Government | Pushpagiri Eye Hospital, Vizianagaram |

| Assam | Kamrup | Dropped | Health Department, Assam Government | Sri Sankaradeva Nethralaya, Guwahati |

| Goa | North/South Goa | May 2016 | Health Department, Goa Government | Goa Medical College, Goa & HV Desai Eye Hospital, Pune |

| Gujarat | Surat | Jan 2017 | Health Department, Gujarat Government | Tejas Eye Hospital, Mandvi |

| Karnataka | Tumkur | Jan 2016 | Health Department, Karnataka Government | Vittala International Institute of Ophthalmology, Bengaluru |

| Kerala | Thrissur | Dec 2016 | Health Department, Kerala Government | Little Flower Hospital, Angamaly |

| Maharashtra | Wardha | June 2016 | Health Department, Maharashtra Government | MGIMS, Sevagram |

| Odisha | Khurda | April 2017 | Health Department, Odisha Government | LV Prasad Eye Institute, Bhubaneshwar |

| Rajasthan | Pali | Aug 2016 | Health Department, Rajasthan Government | Global Hospital & Research Centre, Mt. Abu |

| Tamil Nadu | Tirunelveli | Nov 2016 | Health Department, Tamil Nadu Government | Aravind Eye Care System, Tirunelveli |

| West Bengal | Paschim Medinipur | Mar 2017 | Health Department, West Bengal Government | Vivekananda Mission Asram Netra Niramay Niketan, Chaitanyapur |

Capacity building of the core health personnel and procurement and installation of equipment were emphasized during the initial period in the 60 community development blocks, including 10 district hospitals [Table 2]. In the last year, additional equipment was provided at the behest of the state governments interested in scaling up the pilot to other districts in the state.

Table 2.

Input and process indicators cumulative performance

| Parameter | 2014-15 | 2016 n (%) | 2017 n (%) | 2018 n (%) | 2019 n (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ophthalmologists trained to treat | 11 (27.5) | 20 (50.0) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (10.0) | 40 | |

| Ophthalmic personnel trained in screening | 33 (14.3) | 88 (38.1) | 92 (39.8) | 18 (7.8) | 231 | |

| Health personnel oriented on DR | 1177 (19.4) | 1447 (23.8) | 2393 (39.4) | 1052 (17.3) | 6069 | |

| Tripartite agreements signed | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 10 | |||

| Medical officers oriented on DR | 186 (32.2) | 138 (23.9) | 121 (20.9) | 133 (23.0) | 578 | |

| National task force meetings | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| Implementing partners consortium meetings | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Fundus cameras provided | 20 (16.0) | 30 (24.0) | 34 (27.2) | 41 (32.8) | 125 | |

| Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provided | 2 (16.7) | 4 (33.3) | 3 (25.0) | 3 (25.0) | 12 | |

| Laser delivery systems provided | 4 (22.2) | 6 (33.3) | 5 (27.8) | 3 (16.7) | 18 | |

| No. of blocks/tehsils/talukas covered | 13 | 47 | 60 | |||

| No. of blocks/tehsils/talukas scaling up | 86 |

Overall, 66,455 people with DM were screened during the pilot [Table 3]. Among those screened, 8,148 (12.3%) were referred for confirmatory diagnosis. Any level of DR was observed in DR in 16.2% (10,765). Vision threatening DR was detected in 4974 people with DM, that is, 7.5% of those screened. 4,020 (80.8%) persons with VTDR were treated during the course of the pilot. 6,720 people with DM (10.1% of those who were initially screened) returned for the next annual assessment. A special initiative for type 1 DM (T1DM) was operationalized for the first 2 years and 1,065 persons with T1DM were provided screening and management for DR at three hospitals (AIIMS, New Delhi; Young Diabetes Clinic, Hyderabad; Mohan's Diabetes Specialties, Chennai).

Table 3.

Output indicators cumulative performance

| Parameter | 2016 n (%) | 2017 n (%) | 2018 n (%) | 2019 n (%) Jan-June | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PwDM screened | 4911 (7.4) | 15266 (23.0) | 34492 (51.9) | 11786 (17.7) | 66455 |

| PwDM treated for DR | 252 (6.3) | 1148 (28.6) | 1925 (47.9) | 695 (17.3) | 4020 |

| PwDM attending first annual follow up for DR screening | - | 2157 (32.2) | 3136 (46.8) | 1411 (21.0) | 6704 |

| T1DM screened | 399 (37.5) | 666 (62.5) | 1065 |

Output indicators showed a geometric increase in the number of people with DM screened from 2016 to 2018 [Table 3]. There was a 7-fold increase in the number of people with DM screened and a 7.6-fold increase in the number of people with DM treated during this period. However, the proportion of people with DM returning for a repeat annual DR screening was inadequate as only 10% of those initially screened returned for a repeat screen.

A number of approaches were tried to reach PwDM in the different districts [Table 4]. This varied from a static to a mobile approach; from PHC to CHC as the location for screening; NCD nurse to a paramedical ophthalmic assistant/officer (PMOA/O) being the primary screener, and from standalone DR screening and management to comprehensive management of diabetes and its complications. The numbers were very small to draw conclusions on the most appropriate modality. However, it appears that a static facility with a smaller population base and smaller distances to travel increases uptake of services.

Table 4.

Models of integrated care implemented

| State | Screening location in NCD clinics | Primary person screening | Primary person grading | Location of grading center | Location of DR treatment facilities | PwDM screened per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | CHC/DH | PMOA/O | Ophthalmologist | DH/MH | DH/MH | 1880 |

| Goa | PHC/CHC/SDH | PMOA/O | Ophthalmologist | MH | MH | 3110 |

| Gujarat | CHC/DH | PMOA/O | Ophthalmologist | DH/MH | DH/MH | 1604 |

| Karnataka | CHC/SDH | PMOA/O | Ophthalmologist | DH/Mobile van | DH/MH/Mobile van | 482 |

| Kerala | CHC | PMOA/O | Ophthalmologist | MH | MC | 2349 |

| Maharashtra | PHC/CHC | PMOA/NCD Nurse | Ophthalmologist | MH | MH | 980 |

| Odisha | CHC | PMOA/O | Ophthalmologist | MH | DH/MH | 628 |

| Rajasthan | CHC | MH PMOA/O | Ophthalmologist | MH | MH | 288 |

| Tamilnadu | CHC | NCD Nurse | Ophthalmologist | MH/DH | MH/MC | 858 |

| West Bengal | CHC/DH | PMOA/O | Ophthalmologist | MH | MH/MC | 799 |

| Total | 1020 |

CHC: Community health center; DH: District hospital, NCD: Noncommunicable disease, MC: Medical college, MH: Mentoring partner hospital, PHC: Primary health center, PMOA/O: Paramedical ophthalmic assistant/officer; SDH: Sub-divisional hospital

Discussion

This is the first effort of augmenting the public health system to provide screening and management for DR on such a large scale in India. The pilot was unique in that it brought together the needs of the population, the will of the government and the skills of the mentoring partners to serve a common cause.

Overall approximately 1,000 people with DM were screened per 100,000 population. In this population, 35% would be aged ≥ 35 years and the estimated prevalence of diabetes would be 15%.[3] Therefore, there would be 5,250 people with DM aged 35+ in a population of 100,000. Evidence shows that only 50% of people with DM know that they have diabetes.[1,2,3] Thus, there would be 2,625 known people with DM in this population and with a mixed health system as seen in India, those who can afford services may seek them from the private sector.

In most of the pilot states, the model has been scaled up across other districts with support from the respective governments.

Conclusion

The pilot project has demonstrated that services for detecting and managing DR can be successfully integrated into the existing public health system at the district and sub-district levels. A collaborative approach is required to provide needs-based, context-specific comprehensive diabetic care services to the nearly 75 million people with DM in India.

Financial support and sponsorship

The Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust, London, UK.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Diabetes Collaborators. The increasing burden of diabetes and variations among states in India: The global burden of diseases study 1990-2016. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1352–62. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30387-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Atlas 2017. [Last accessed on 2018 Jun 18]. Available from: https://reports.instantatlas.com/report/view/704ee0e6475b4af885051bcec15f0e2c/IND .

- 3.Anjana RM, Deepa M, Pradeepa R, Mahanta J, Narain K, Das HK, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes in 15 states of India: Results from the ICMR-INDIAB population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:585–96. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raman R, Ganesan S, Pal SS, Kulothungan V, Sharma T. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in rural India. Sankara Nethralaya diabetic retinopathy epidemiology and molecular genetic study III (SN-DREAMS III), report no 2. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2014;2:e000005. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2013-000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunita M, Singh AK, Rogye A, Sonawane M, Gaonkar R, Srinivasan R, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in urban slums: The Aditya Jyot diabetic retinopathy in urban Mumbai slums study-report 2. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2017;24:303–10. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2017.1290258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang QH, Zhang Y, Zhang XM, Li XR. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy, proliferative diabetic retinopathy and non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy in Asian T2DM patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2019;12:302–11. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2019.02.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Indian Institute of Public Health, Hyderabad. Guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic eye disease in India. Version 1, June 2019. Hyderabad, India: Indian Institute of Public Health, Hyderabad; 2019. pp. 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shukla R, Gudlavalleti MV, Bandyopadhyay S, Anchala R, Gudlavalleti AS, Jotheeswaran AT, et al. Perception of care and barriers to treatment in individuals with diabetic retinopathy in India: 11-city 9-state study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;20(Suppl 1):S33–41. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.179772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Bank. Rural population (% of total population): India. [Last accessed on 2019 Sep 11]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS .

- 10.Gilbert CE, Babu GR, Gudlavalleti ASV, Anchala R, Shukla R, Pant BH, et al. Eye care infrastructure and human resources for managing diabetic retinopathy in India: The India 11-city 9-state study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;20(Suppl 1):S3–10. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.179768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]