INTRODUCTION

Mental health professionals in India have always involved families in therapy. However, formal involvement of families occurred about one to two decades after this therapeutic modality was started in the West by Ackerman.[1] In India, families form an important part of the social fabric and support system, and as a result, they are integral in being part of the treatment and therapeutic process involving an individual with mental illness. Mental illnesses afflict individuals and their families too. When an individual is affected, the stigma of being mentally ill is not restricted to the individual alone, but to family members/caregivers also. This type of stigma is known as “Courtesy Stigma” (Goffman). Families are generally unaware and lack information about mental illnesses and how to deal with them and in turn, may end up maintaining or perpetuating the illness too. Vidyasagar is credited to be the father of Family Therapy in India though he wrote sparingly of his work involving families at the Amritsar Mental Hospital.[2] This chapter provides salient features of broad principles for providing family interventions for the treating psychiatrist.

TYPES AND GRADES FOR FAMILY INTERVENTIONS

Working with families involves education, counseling, and coping skills with families of different psychiatric disorders. Various interventions exist for different disorders such as depression, psychoses, child, and adolescent related problems and alcohol use disorders. Such families require psychoeducation about the illness in question, and in addition, will require information about how to deal with the index person with the psychiatric illness. Psychoeducation involves giving basic information about the illness, its course, causes, treatment, and prognosis. These basic informative sessions can last from two to six sessions depending on the time available with clients and their families. Simple interventions may include dealing with parent-adolescent conflict at home, where brief counseling to both parties about the expectations of each other and facilitating direct and open communication is required.

Additional family interventions may cover specific aspects such as future plans, job prospects, medication supervision, marriage and pregnancy (in women), behavioral management, improving communication, and so on. These family interventions offering specific information may also last anywhere between 2 and 6 sessions depending on the client's time. For example, explaining the family about the marriage prospects of an individual with a psychiatric illness can be considered a part of psychoeducation too, but specific information about marriage and related concerns require separate handling. At any given time, families may require specific focus and feedback about issues such issues.

Family therapy is a structured form of psychotherapy that seeks to reduce distress and conflict by improving the systems of interactions between family members. It is an ideal counseling method for helping family members adjust to an immediate family member struggling with an addiction, medical issue, or mental health diagnosis. Specifically, family therapists are relational therapists: They are generally more interested in what goes on between the individuals rather than within one or more individuals. Depending on the conflicts at issue and the progress of therapy to date, a therapist may focus on analyzing specific previous instances of conflict, as by reviewing a past incident and suggesting alternative ways family members might have responded to one another during it, or instead proceed directly to addressing the sources of conflict at a more abstract level, as by pointing out patterns of interaction that the family might not have noticed.

Family therapists tend to be more interested in the maintenance and/or solving of problems rather than in trying to identify a single cause. Some families may perceive cause-effect analyses as attempts to allocate blame to one or more individuals, with the effect that for many families, a focus on causation is of little or no clinical utility. It is important to note that a circular way of problem evaluation is used, especially in systemic therapies, as opposed to a linear route. Using this method, families can be helped by finding patterns of behavior, what the causes are, and what can be done to better their situation. Family therapy offers families a way to develop or maintain a healthy and functional family. Patients and families with more difficult and intractable problems such as poor prognosis schizophrenia, conduct and personality disorder, chronic neurotic conditions require family interventions and therapy. The systemic framework approach offers advanced family therapy for such families. This type of advanced therapy requires training that very few centers, such as the Family Psychiatry Center at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India offer to trainees and residents. These sessions may last anywhere from eight sessions up to 20 or more on occasions [Table 1].

Table 1.

Types and grades of family interventions

| Family psychoeducation (basic information) | Family interventions (specific information) | Family therapy (systemic framework) |

|---|---|---|

| Depression and anxiety | Medication supervision | Schizophrenia with poor prognosis |

| Schizophrenia and bipolar disorders (psychoses) | Marriage and pregnancy counseling | Conduct and personality disorders |

| Alcohol use disorders | Job-related counseling | Chronic neurotic conditions |

| Child and adolescent conditions/issues | Future plans- education, stress | Severe expressed emotions |

| Organic brain disorders | Coping and stigma | Family discord and major conflicts |

| Any other illness | Behavioral management (e.g., contracting) | |

| Improving communication |

Goals of family therapy

Usual goals of family therapy are improving the communication, solving family problems, understanding and handling special family situations, and creating a better functioning home environment. In addition, it also involves:

Exploring the interactional dynamics of the family and its relationship to psychopathology

Mobilizing the family's internal strength and functional resources

Restructuring the maladaptive interactional family styles (including improving communication)

Strengthening the family's problem-solving behavior.

Reasons for family interventions

The usual reasons for referral are mentioned below. However, it may be possible that sometimes the reasons identified initially may be just a pointer to many other lurking problems within the family that may get discovered eventually during later assessments.

Marital problems

Parent–child conflict

Problems between siblings

The effects of illness on the family

Adjustment problems among family members

Inconsistency parenting skills

Psychoeducation for family members about an index patient's illness

Handling expresses emotions.

CHALLENGES FACED BY THE NOVICE THERAPIST

Whether one is a young student, or a seasoned individual therapist, dealing with families can be intimidating at times but also very rewarding if one knows how to deal with them. We have outlined certain challenges that one faces while dealing with families, especially when one is beginning.

Being overeager to help

This can happen with beginner therapists as they are overeager and keen to help and offer suggestions straight away. If the therapist starts dominating the interaction by talking, advising, suggesting, commenting, questioning, and interpreting at the beginning itself, the family falls silent. It is advisable to probe with open-ended questions initially to understand the family.

Poor leadership

It is advisable for the therapist to have control over the sessions. Sometimes, there may be other individuals/family members who maybe authoritative and take control. Especially in crisis situations, when the family fails to function as a unit, the therapist should take control of the session and set certain conditions which in his professional judgment, maximize the chances for success.

Not immersing or engaging/fear or involving

A common problem for the beginning therapist is to become overly involved with the family. However, he may realize this and try to panic and withdraw when he can become distant and cold. Rather, one should gently try to join in with the family earning their true respect and trust before heading to build rapport.

Focusing only on index patient

Many families believe that their problem is because of the index patient, whereas it may seem a tactical error to focus on this person initially. In doing so, it may essentially agree to the family's hypothesis that their problem is arising out of this person. It is preferable, at the outset to inform the family that the problem may lie with the family (especially when referrals are made for family therapies involving multiple members), and not necessarily with any one individual.

Not including all members for sessions

Many therapeutic efforts fail because important family members are not included in the sessions. It is advisable to find out initially who are the key members involved and who should be attending the sessions. Sometimes, involving all members initially and then advising them to return to therapy as and when the need arises is recommended.

Not involving members during sessions

Even though one has involved all members of the family in the sessions, not all of them may be engaged during the sessions. Sometimes, the therapist's own transference may hold back a member of the family in the sessions. Rather, it is recommended that the therapist makes it clear that he/she is open to their presence and interactions, either verbally or nonverbally.

Taking sides with any member of the family

It may be easy to fall into the trap of taking one member's side during sessions leaving the other party doubting the fairness and judgment of the therapist. For example, after meeting one marital partner for a few sessions, the therapist, when entering the couple, discussions may be heavily biased in his views due to his/her prior interaction. Therapists should be aware of this effect and try to be neutral as possible yet take into confidence each member attending the sessions. Therapist's countertransference can easily influence him/her to take sides, especially in families that are overtly blaming from the start, or with one member who may be aggressive in the sessions, or very submissive during the sessions can influence the therapist's sides; and one needs to be aware of this early in the sessions.

Guarded families

Some families put on a guarded façade and refuse to challenge each other in the session. By being neutral and nonjudgmental, sometimes, the therapist can perpetuate this guarded façade put forth by families. Hence, therapists must be able to read this and try to challenge them, listen to microchallenges within the family, must be ready to move in and out from one family member to another, without fixing to one member.

Communicating with the therapist outside sessions

Many families attempt to reduce tension by communicating with therapist outside the session, and beginning therapist are particularly susceptible for such ploys. The family or a member/s may want to meet the therapist outside the sessions by trying to influence the therapist to their views and opinions. Therapists must refrain from such encounters and suggest discussing these issues openly during the sessions. Of course, rarely, there may be sensitive or very personal information that one may want to discuss in person that may be permissible.

Ignoring previous work done by other therapists

It is easy for family therapists to ignore previous therapists. The family therapist's ignorance of the effects of previous therapy can serious hamper the work. By discussing the previous therapist helps the new therapist to understand the problem easily and could save time also.

Getting sucked to the family's affective state/mood

If transference involves the therapist in family structure, the therapist's dependency can overinvolved him in the family's style and tone of interaction. A depressed family causes both: Therapist to relate seriously and sadly. A hostile family may cause the therapist to relate in an attacking manner. The most serious problem can occur when a family is in a state of anxiety, induces the therapist to become anxious and make his/her comments to seem accusatory and blaming. It is very difficult for the beginning therapist to “feel” where the family is affectively, to be empathic, yet to be able to relate at times on a different affective level-to respond according to situations. It is important to be aware of the affective state/mood of the family but slips in and out of that state [Table 2].

Table 2.

Guidelines for conducting interventions with families

| Timings for appointments to be followed for smooth conduct of sessions |

| Arriving late may reduce actual session time by the same margin |

| Any cancellation or postponement of sessions to be informed in advance by both parties |

| Session location would be intimated in advance |

| An approximate total number of expected family sessions to be informed in the beginning; including frequency of the sessions |

| Inform clients about the reason why the family is being seen together |

| Advise clients that changes may occur gradually after assessments and immediate solutions may not be provided as far as possible |

| The duration of the sessions would be informed in the beginning itself (45 min to an hour) |

| Any other matters arising, in the end, can brought up during subsequent sessions |

| During sessions, clients to refrain from interrupting when someone else is talking |

| Family members to wait for turns to talk as everyone would be given the opportunity |

| Clients to avoid verbal arguments or fights during the sessions |

| Inform clients about the confidentiality of the contents of the sessions and record-keeping practices |

| Clients to avoid any discussions outside of therapy sessions with the therapist |

| Clients to discuss relevant matters as far as possible in the sessions even though some matters may be conflicting in nature |

| Make a formal contract with the family about roles of therapist and the family members |

| In families with violence, a no-violence contract is preferable during the entire process of family therapy |

FUNCTIONS OF A FAMILY THERAPIST

The family therapist establishes a useful rapport: Empathy and communication among the family members and between them and himself

-

The therapist uses the rapport to evoke the expression of major conflicts and ways of coping.

- The therapist clarifies conflict by dissolving barriers, confusions, and misunderstandings

- Gradually, the therapist attempts to bring to the family to a mutual and more accurate understanding of what is wrong

-

This he achieves through a series of partial interventions, which include.

- Counteracting inappropriate denials, conflicts

- Lifting hidden intrapersonal conflict to the level of interpersonal interaction.

The therapist fulfills in part the role of true parent figure, a controller of danger, and a source of emotional support and satisfaction-supplying elements that the family needs but lacks. He introduces more appropriate attitudes, emotions, and images of family relations than the family has ever had

The therapist works toward penetrating (entering into) and undermining resistances and reducing the intensity of shared currents of conflict, guilt, and fear. He accomplishes these aims mainly using confrontation and interpretation

The therapist serves as a personal instrument of reality testing for the family.

In carrying out these functions, the family therapist plays a wide range of roles, as:

An activator

Challenger

Supporter

Interpreter

Re-integrator

Educator.

BASIC STEPS FOR FAMILY INTERVENTIONS

The initial phase of therapy

The referral intake

Family assessment

Family formulation and treatment plan

Formal contract.

The referral intake

Patients and their families are usually referred to as some family problem has been identified. The therapist may be accustomed to the usual one-on-one therapeutic situation involving a patient but may be puzzled in his approach by the presence of many family members and with a lot of information. A few guidelines are similar to the approaches followed while conducting individual therapy. The guidelines for conducting family interventions are given in Table 2. At the time of the intake, the therapist reviews all the available information in the family from the case file and the referring clinicians. This intake session lasts for 20–30 min and is held with all the available family members. The aim of the intake session is to briefly understand the family's perception of their problem, their motivation and need to undergo family intervention and the therapist assessments of suitability for family therapy. Once this is determined the nature and modality of the therapy is explained to the family and an informal contract is made about modalities and roles of therapist and the family members. The do's and don’ts of the family interventions are laid down to the family at the outset of the process of the interventions.

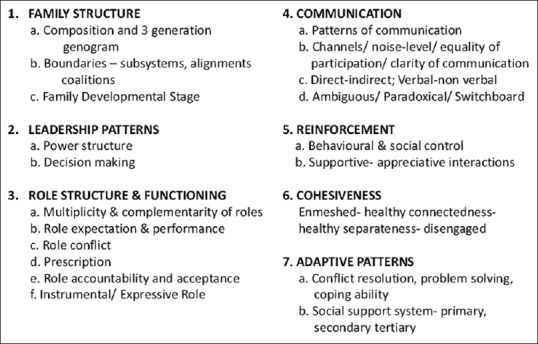

The family assessment and hypothesis

The assessment of different aspects of family functioning and interactions must typically take about 3–5 sessions with the whole family, each session must last approximately 45 min to an hour. Different therapists may want to take assessments in different ways depending on their style. Mentioned below are a few tasks which are recommended for the therapist to perform. Usually, it is recommended that the naïve therapist starts with a three-generation genogram and then follows-up with the different life cycle stages and family functions as outlined below.

The three-generation genogram is constructed diagrammatically listing out the index patient's generation and two more related generations, for example, patients and grandparents in an adolescent client or parents and children in a middle-aged client. The ages and composition of the members are recorded, and the transgenerational family patterns and interactions are looked at to understand the family from a longitudinal and epigenetic perspective. The therapist also familiarizes himself with any family dynamics prior to consultation. This gives a broad background to understand the situation the family is dealing with now

The life cycle of the index family is explored next. The functions of the family and specific roles of different members are delineated in each of the stages of the family life cycle.[3] The index family is seen from a developmental perspective, and the therapist gets a longitudinal and temporal perspective of the family. Care is taken to see how the family has coped with problems and the process of transition from one stage to another. If children are also part of the family, their discipline and parenting styles are explored (e.g., whether there is inconsistent parenting)

Problem Solving: Many therapists look at this aspect of the family to see how cohesive or adaptable the family has been. Usually, the family members are asked to describe some stress that the family has faced, i.e., some life events, environmental stressors, or illness in a family member. The therapist then proceeds to get a description of how the family coped with this problem. Here, “circular questions” are employed and therapist focuses on antecedent events. The crisis and the consequent events are examined closely to look for patterns that emerge. The family function (or dysfunction) is heightened when there is a crisis situation and the therapist look at patterns rather than the content described. Thus, the therapist gets an “as if I was there” view of the family. The same inquiry is possible using the technique of enactment[4]

The Structural Map: Once the inquiry is over, the therapist draws the structural map, which is a diagrammatic representation of the family system, showing the different subsystems, its boundaries, power structure and relationships between people. Diagrammatic notions used in structural therapy or Bowenian therapy are used to denote relationships (normal, conflictual, or distant) and subsystem boundaries, in different triadic relationships. This can also be done on a timeline to show changes in relationships in different life cycle stages and influences from different life events

-

The Circular Hypothesis: A systemic family hypothesis is now postulated by looking at the function of symptoms for both the client and his family. Answers to the following questions provide the circular hypothesis:

- What the client is trying to convey through his/her symptoms?

- What is the role of the family in maintaining these symptoms?

- Why has the family come now?

This circular hypothesis can be confirmed on further inquiry with the family to see how the “dysfunctional equilibrium” is maintained. At this stage, we suggest that a family formulation is generated, hypothesized and analyzed. This leads to a comprehensive systemic formulation involving three generations. This formulation will determine which family members we need to see in a therapy, what interventional techniques we should use and what changes in relationships we should effect. The team will also discuss the minimum, most effective treatment plan which emerges considering the most feasible changes the family can make

Formal Contract: A brief understanding of the family homeostasis is presented to the family. Sometimes, the full hypothesis may be fed to the family in a noncritical and positive way (“Positive Connotation”), appreciating the way in which the system is functioning the therapist presents the treatment plat to the family and negotiates with the members the plan and action they would like to take up at the present time. The time frame and modality of therapy is contracted with the family, and the therapy is put into force. The frequency and intensity of sessions are determined by the degree of distress felt by the family and the geographical distance from the therapy center, i.e., families may be seen as inpatients at the center if they are in crisis or if they live far away.

The Family Psychiatry Center at The NIMHANS, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India, is one of the centers where formal training in therapy is regularly conducted. An outline of the Family Assessment Proforma[5] used at this center is given in Figure 1. Several other structured family assessment instruments are available [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Family assessment proforma (Obtained with permission from the Family Psychiatry Center, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India)

Middle phase of therapy

This phase of therapy forms the major work that is carried out with the family. Depending on the school of therapy, that is used, these sessions may number from a few (strategic) to many sessions lasting many months (psychodynamic). The techniques employed depend on the understanding of the family during the assessment as much as the family – therapist fit. For example, the degree of psychological sophistication of the clients will determine the use of psychodynamic and behavioral techniques. Similarly, a therapist who is comfortable with structural/strategic methods would put these therapies to maximum use. The nature of the disorder and the degree of pathology may also determine the choice of therapy, i.e., behavioral techniques may be used more in chronic psychotic conditions while the more difficult or resistant families may get brief strategic therapies. We will now describe some of the important techniques used with different kinds of problems.

Psychodynamic therapy

This school was one of the first to be described by people like Ackerman and Bowen.[1,6] This method has been made more contextual and briefer by therapists like Boszormenyi-Nasgy and Framo.[7,8] Essentially, the therapist understands the dynamics employed by different members of the family and the interrelationships of these members. These family ego defenses are interpreted to the members and the goal of therapy is to effects emotional insight and working through of new defense patterns. Family transferences may become evident and may need interpretation. Therapy usually lasts from 15 to 30 sessions and this method may be employed in persons who are psychologically sophisticated, and able to understand dynamics and interpretations. Sustained and high motivation is necessary for such a therapy. This method is found useful in couples with marital discord from upper middle-class backgrounds. Time required is a major constraint.

Behavioral methods

Behavioral techniques find use in many types of therapies and conditions. It has been extensively used in chronic psychotic illnesses by workers such as Fallon et al., (1986) and Anderson et al.[9,10] Psychoeducation and skills training in communication and problem-solving are found very useful among families which do not have very serious dysfunction. Techniques such as modeling or role-plays are useful in improving communication styles and to teach parenting skills with disturbed children. Obviously, motivation for therapy is a major requisite and hence techniques such as contracting, homework assignments are used in couples with marital discord. Behavioral techniques used in sexual dysfunction are also possible when adapted according to clients’ needs.

Structural family therapy

Described by Minuchin; Fishman and Unbarger[4,11,12] has become quite popular over the past few years among therapists in India. This is possibly because of many reasons. Our families are available with their manifold subsystems of parents, children, grandparents and structure is easily discerned and changed. In addition, in recent years most clients present with conduct and personality disorders in adolescence and early adulthood. Hence, techniques like unbalancing, boundary-making are quite useful as the common problems involve adolescents who are wielding power with poor marital adjustments between parents. These techniques are useful for many of our clients.

Strategic technique

We have found that these brief techniques can be very powerfully used with families which are difficult and highly resistant to change. We usually employ them when other methods have failed, and we need to take a U-turn in therapy. Techniques employed by the Milan school[13,14] reframing, positive connotation, paradoxical (symptom) prescription have been used effectively. So also have techniques like prescription in brief methods advocated by Erikson, Watzlawick et al.,[15,16] been useful. Familiarity and competence with these techniques is a must and therapy is usually brief and quickly terminated with prescriptions [Table 3].

Table 3.

Summaries of the different schools of therapies

| School of therapy | Key elements | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Psychodynamic therapy | Based on psychoanalysis; emphasis on conscious and unconscious processes; the past issues are still dynamic in the current setting; early life experiences are significant; intrapersonal and interpersonal processes are entangled | Change is steady; requires long-term investment (20-40 sessions); psychological mindedness of client required |

| Behavioral methods | Maladaptive behaviors, not underlying causes, should be the targets of change; not required to treat the entire family; the therapist is the expert, teacher, collaborator, and coach | Parent-skills training and behavioral treatment of sexual dysfunctions are examples; treatment is short term |

| Structural family therapy | Symptoms are understood in terms of family interaction patterns, family organization must change before symptom reduction; emphasis on the whole family and its subunits; therapist joins, maps out, and helps transform family | Especially useful with juvenile delinquents, alcohol use and anorexia, low SES families, and cross-cultural populations |

| Strategic technique | Not helpful to tell families what they are doing wrong; behavior change must precede other changes; directives from therapist are instructions given to family, necessary to make changes within the first three sessions | Short-term treatment; techniques are very innovative; useful in eating disorders and substance use |

SES – Socioeconomic status

FAMILY INTERVENTIONS IN SPECIFIC DISORDERS

Techniques to promote family adaptation to illness

Heighten awareness of shifting family roles – pragmatic and emotional

Facilitate major family lifestyle changes

Increase communication within and outside the family regarding the illness

Help family to accept what they cannot control, focus energies on what they can

Find meaning in the illness. Help families move beyond “Why us?”

Facilitate them grieving inevitable losses–of function, of dreams, of life

Increase productive collaboration among patients, families, and the health-care team

Trace prior family experience with the illness through constructing a genogram

Set individual and family goals related to illness and to nonillness developmental events.

Schizophrenia

Family EE and communication deviance (or lack of clarity and structure in communication) are well-established risk factors for the onset of schizophrenia.

Psychoeducational interventions aim to increase family members’ understanding of the disorder and their ability to manage the positive and negative symptoms of psychosis.

Simple strategies would include reduction of adverse family atmosphere by reducing stress and burden on relatives, reduction of expressions of anger and guilt by the family, helping relatives to anticipate and solve problems, maintenance of reasonable expectations for patient performance, to set appropriate limits whilst maintaining some degree of separation when needed; and changing relatives’ behavior and belief systems.

Programs emphasize family resilience. Address families’ need for education, crisis intervention, skills training, and emotional support.

Bipolar mood disorder

To recognize the early signs and symptoms of bipolar disorder.

Develop strategies for intervening early with new episodes and assure consistency with medication regimens.

Manage moodiness and swings of the patient, anger management, feelings of frustration.

Depression

Family conflict and rejection, low family support, ineffective communication, poor expression of affect, abuse, and insecure attachment bonds are primary focus of family therapy associated with depression cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal interventions for depression.

Anxiety

Family-based treatment for anxiety combines family therapy with cognitive-behavioral interventions.

Targets the characteristics of the family environment that support anxiogenic beliefs and avoidant behaviors.

The goal is to disrupt the interactional patterns that reinforce the disorder.

To assist family members in using exposure, reward, relaxation, and response prevention techniques to reduce the patients’ anxieties.

Eating disorders

Target the dysfunctional family processes, namely, enmeshment and overprotectiveness.

To help parents build effective and developmentally appropriate strategies for promoting and monitoring their child's eating behaviors.

Childhood disorders

The primary focus is the development of effective parenting and contingency management strategies that will disrupt the problematic family interactions associated with ADHD and ODD.

Family-based interventions for autism spectrum disorder

Parents taught to use communication and social training tools that are adapted to the needs of their children and apply these techniques to their family interactions at home.

Substance misuse

Enhance the coping ability of family members and reduce the negative consequences of alcohol and drug abuse on concerned relatives; eliminate the family factors that constitute barriers to treatment; use family support to engage and retain the drug and/or alcohol user in therapy; change the characteristics of the family environment that contribute to relapse Al-Anon, AL-teen.

Termination phase

This last phase of therapy is finished in a couple of sessions. The initial goals of therapy are reviewed with the family. The family and the therapist review together the goals which were achieved, and the therapist reminds the family the new patterns/changes which have emerged. The need to continue these new patterns is emphasized. At the same time, the family is cautioned that these new patterns will occur when all members make a concerted effort to see this happen. Family members are reminded that it is easy to fall back to the old patterns of functioning which had produced the unstable equilibrium necessitating consultation.

At termination, the therapist usually negotiates new goals, new tasks or new interactions with the family that they will carry out for the next few months in the follow up period. The family is told that they need to review these new patterns after a couple of months so as to determine how things have gone and how conflicts have been addressed by the family. This way the family has a better chance of sustaining the change created. Sometimes booster sessions are also advised after 6–12 months especially for outstation families who cannot come regularly for follow-ups. These booster sessions will review the progress and negotiate further changes with the family over a couple of sessions. This follow-up period, after therapy is terminated is crucial for working through process and ensures that the client-therapist bond is not severed too quickly. It is easy to deal with the clients’ and therapist’ anxieties if this transition phase is smooth.

SPECIAL SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES IN THERAPY SPECIFIC TO INDIA

Most Indian families are functionally joint families though they may have a nuclear family structure. Furthermore, unlike the Western world more than two generations readily come for therapy. Hence, it becomes necessary to deal with two to three generations in therapy and also with transgenerational issues. Our families also foster dependency and interdependency rather than autonomy. This issue must also be kept in mind when dealing with parent–child issues. Indians have a varied cultural and religious diversity depending on the region from which the family comes. The therapist has to be familiar with the regional customs, practices, beliefs, and rituals. The Indian family therapist has to also be wary of being too directive in therapy as our families may give the mantle of omnipotence to the therapist and it may be more difficult for us to adopt at one-down or nondirective approach. Hence, while systemic family therapy is eminently possible in India one must keep in mind these sociocultural factors so as to get a good “family-therapist fit.”

Constraint factors in therapy

The economic backwardness of most out families makes therapy feasible and affordable, in terms of time and money spent, only to the middle and upper classes of our society. The poorer families usually drop out of therapy as they have other more pressing priorities. The lack of tertiary social support and welfare or social security makes it less possible to network with other systems. We are also woefully inadequate in terms of trained family therapists to cater to our large population. In our country, distances seem rather daunting and modes of transport and communication are poor for families to readily seek out a therapist. We work with these constraint factors and so the “family-therapy” fit is an important factor for families that are seeking and staying in family therapy.17

CONCLUSIONS

Over the last few years, a systemic model has evolved for service and for training. The model uses a predominantly systematic framework for understanding families and the techniques for therapy are drawn from different schools namely the structural, strategic, and behavioral psychodynamic therapies.

Appendix: Glossary of terms

Structure

The repetitive patterns of interaction that organize the way in which family members relate and interact with each other.

Boundaries

Boundaries are the rules defining who participates in the system and how, i.e., the degree of access outsiders have to the system.

Subsystem

It may comprise of a single person, or several persons joined together by common membership criteria, for example, age, gender, or shared purpose.

Coalition

When alignments stand in opposition to another part of the system (i.e., when several family members are against another member/s.

Alliance

The joining together of two or more members. It popularly designates appositive affinity between two units of a system.

Channels of communication are a mechanism that defines “who speaks to whom.” When channels of communication are blocked, needs cannot be fulfilled, problems cannot be solved, and goals cannot be achieved.

Enmeshed families

In which, there is extreme sensitivity among the individual members to each other and their primary subsystem.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackerman NW. New York: Basic Books; 1966. Treating the Troubled Family. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vidyasagar . Vol. 19. New Delhi: World Health Organization, SEA; 1971. Innovations in Psychiatric Treatment at Amritsar Mental Hospital. Report on a Seminar on the Organization and Future Needs of Mental Health Services. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duval E. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1967. Family Development. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unbarger C. Structural Family Therapy. Now York: Grune and Stratton; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bengaluru: Family Psychiatry Center, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences; 2001. Family Psychiatry Center, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences. Family Assessment Proforma. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen M. The use of family theory in clinical practice. In: Haley J, editor. Changing Families. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boszormenyi-Nasgy I. Contextual therapy: Therapeutic leverages in mobilizing Trust. In: Green RJ, Framo JL, editors. Family Therapy: Major Contributions. New York: International University Press, Inc; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Framo JL. Cambridge; 1985. Family of Origin as a Therapeutic Resource for Adults in Marital and Family Therapy. Year Care Seminar-Family Therapy; pp. 151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fallon IR, Boyd JL, McGill CW. New York: Gillford Press; 1984. Family Care of Schizophrenia. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, Hogarty GE. New York: Guilkd Ford Press; 1986. Schizophrenia in the family? A Practitioners Guide to Psychoeducation and Management. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minuchin S. London: Tavistock Publications; 1974. Families and Family Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishman HC. Treating Troubled Adolescents – A Family Therapy Approach. London: Hutchinson; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palazzoli Selvini M, Boscolo L, Cecehin G. Vol. 19. Family Process; 1980. Hypothesizing- Circularity Neutrality: Three Guidelines for the Conductor of the Session; pp. 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomm K. One prespective on the Milan systemic approach. Part 11. Description of session format. Interviewing style and interventions. J Marital Fam Ther. 1984;10:253–71. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erikson M. Indirect hypnotherapy of a bedwetting couple. In: Haley J, editor. Changing Families. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watzlawick P, Weakland J, Fisch R. New York: W.W. Norten; 1974. Change: Principles of Problems Formation and Problem Resolution. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varghese M, Bhatti RS, Rahguram A, Chandra PS, Udaya Kumar GS, Shah A. Training in family therapy at NIMHANS. In: Kapur M, Sharma Sunder C, Bhatti RS, editors. Psychotherapy Training In India. Vol. 36. NIMHANS Publication; 2001. pp. 112–5. [Google Scholar]