INTRODUCTION

Sexual functioning is not only a coordinated process of body systems – the vascular, endocrine, and neurological – but also a complex bio-psycho-social process. Compounding these are the factors such as societal and religious beliefs, health status, personal experience, ethnicity and sociodemographic conditions, and psychological status of the person/couple. All these together interplay a coordinated response for sexual functioning. Any interference in each of these systems and factors can lead to sexual dysfunction (SD). It affects many men and equal number of women across their lifetime.

As much it plays a role in species propagation, the human sexual functioning is also recreationally, psychologically, and spiritually important. Any problem in sexual functioning affects the quality of life, emotional bonding among couples, and marital disharmony, in many.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Epidemiological survey done in the United States reported that more than 30% of men and 40% of women suffer from some form of SD, with premature ejaculation (PME) in men (21%) and low sexual desire in women (22%) being the most common. There are similar figures from European countries where 34% women and 15% men reported low sexual desire. Looking at an Indian perspective, a study conducted at Chandigarh found a diagnosis of sexual problems in 10% of males attending psychiatry and medical outpatient department. In another study, among rural population of South India, it was noticed that of study population those above 60 years of age and sexually active, erectile dysfunction (ED) was reported in 43.5% of males, PME in 10.9%, hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in 0.77%, and anorgasmia in 0.38%. However, data of female population showed that 28% had arousal dysfunction, 16% had HSDD, 20% had anorgasmia, and 8% had dyspareunia.

NOSOLOGICAL SYSTEMS AND THE INDIAN CONTEXT

A common problem of western nosological systems is that it is difficult to establish diagnosis of SD in an Indian context. As shown in table 1 are comparison of the commonly diagnosed sexual dysfunctions in ICD 10 & DSM5. Many of SDs commonly encountered by Indian clinicians are not included in these classifications, taking into account the vast diversities in culture, belief systems, religion, and educational level. Indian researchers have consistently alluded to the existence of certain unique socioculturally determined sexual clinical conditions, such as Dhat syndrome and apprehension about potency. Even though Dhat syndrome finds itself a coding in ICD-10 under other neurotic disorders (F48.8), the diagnosis of apprehension about potency does not find even a mention. A commonly held belief in most of the Indian subcultures about masturbation and “night falls” resulting in loss of potency and affecting marital conjugal relations does not correlate with western nosology. In many culture, masturbation is considered to be responsible for watery semen or sideways curvature or shrinkage of penis. The exaggerated apprehensions in males centered societies on sexual performance on “ First wedding night (Suhaag raat)” commonly the performance anxiety also need special mention. Leucorrhea with or without infective origin is considered as female Dhat syndrome.

Table 1.

Comparison of diagnostic categories of ICD-10 and DSM-5 of sexual disorders (Avasthi et al., 2017)

| Disorders according to sexual cycle | ICD-10 | DSM 5 |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual desire disorders | Lack or loss of sexual desire Sexual aversion Excessive sexual drive |

Male hypoactive sexual desire disorder Female sexual interest/arousal disorder |

| Sexual arousal disorders | Failure of genital response | Male Erectile disorder |

| Orgasm disorders | Orgasmic dysfunction Lack of sexual enjoyment Premature ejaculation |

Male Premature (early) ejaculation Delayed ejaculation Female Orgasmic disorder |

| Sexual pain disorders | Nonorganic dyspareunia Nonorganic vaginismus |

Female Genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder Substance/medication induced sexual dysfunction |

| Other sexual disorders | Paraphilias Gender identity disorders Other sexual dysfunction, not caused by organic disorder or disease Unspecified sexual dysfunction, not caused by organic disorder or disease |

Paraphilic disorders Gender dysphoria Gender dysphoria in children Gender dysphoria in adolescent and adults Other specified gender dysphoria Unspecified gender dysphoria |

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT

A patient-centered frame work is required for better evaluation and management of sexual problems. Principles of evidence-based medicine may be followed in both men and women in diagnostic and treatment planning and adoption of common management approaches for SD. Despite all the advancement in the knowledge and research of sexual medicines, marital therapy and behavioral therapies remain the mainstay of management of SD. The guidelines aim to serve the purpose of enlisting key principles of marital therapy and behavior therapies for the treatment of SD.

As a core principle, practicing clinicians are expected to consciously adopt the patient's perspective and respect the feelings, expectations, ideas, and values of their patients. Some of the basic principles of patient-centered approach are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Principles of treatment

| Let them be involved - Inform the patient about all the available choices and guide them make a choice |

| Provide information - To the patient in an unbiased manner about different treatment options, their pros and cons |

| Let them help you choose the treatment options out of available modalities |

| Provide adequate information about the treatment selected, including advice on what to do and whom to contact in case of side effects, problems and complications |

| In case patient does not have a partner or unable to bring their partner, do not deny treatment |

| Document the mutually agreed treatment goals |

FORMULATION

After complete assessment, the first step in the management is to provide the patient/couple a brief and simple account of the nature of their problems and possible contributory factors are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Nature of the problem & contributory factors

| Aim | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Help the couple to understand their difficulties | Helps mollify the anxieties regarding their problem |

| Enumerating contributory/maintaining factors | Helps establish a rationale for the treatment approach |

| Formulation in the end | Take feedback to whether the person/couple has correctly interpreted the information |

| Understanding the role/contribution of each partner to the problem | Highlights the need to strike a balance between the partners |

| Emphasizing the need of collaboration between the partners and on the positive aspects of their relationship | Important for success of therapy |

| Therapist to be nonjudgmental | Helps avoiding treatment failure |

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Treatments for various SDs can be by classified into general and specific measures. Sex education and relaxation exercises are primary modalities as a general measure of treatment, while the specific measures can be either of pharmacological treatments and nonpharmacological measures such as behavior therapy or a combination of both.

The nonpharmacological management spectrum has an array of options including many types of psychotherapies, such as Master Johnson's behavioral therapy or its modifications, interpersonal, psychodynamic, rational emotive therapy, systematic desensitization, ban on sexual intercourse, and skill training in communication of sexual preferences. There is a lack of comparative analytical study evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of these psychotherapies. The available data through studies have purposive sampling, do not describe their sample adequately, have not used verified or standard definitions for various disorders, and have neglected the therapist variables. Results available from such studies cannot be generalized. The behavioral measures of Master Johnson or its modifications are the most popular and have been found to be most useful among all the techniques, which have been used.

SELECTION OF TREATMENT

The final selection of treatment relies on patient/couple's choice. As a prerequisite, the therapist should inform the patient/couple about the available modalities which would help them make a reasoned choice. Before the start of treatment, agreed treatment goals need to be established. As a part of initial evaluation, therapist should start by taking a detailed psychosexual history which can also involve screening questionnaires to assess the sexual knowledge and attitude. Second, the basic investigations to rule out any physical pathology should me a must on checklist. This approach helps to ascertain the type(s) of SD.

As discussed, the first step involves establishing the probable etiological basis of the dysfunction, i.e., differentiating the dysfunction as organic in origin, psychological in origin, or a combination of both. In case of organic origin of SD, refer the patient to the concerned specialists and investigate and treat accordingly. Some patients may have psychological factors, contributing to maintenance of SD of organic origin. These patients are difficult to treat as they require very good liaison between the psychiatrist and the physicians, wherein the physician should also have adequate knowledge and the right approach to treat the patient in co care.

Patients diagnosed with psychogenic SD should be evaluated for sexual knowledge, relationship issues, presence of comorbid psychiatric disorder, motivation, and psychological sophistication of the patient for treatment.

An important aspect of treatment of SD is assessing the sexual knowledge and relationship issues, as many a time the patient/couple may not have any SD per se, but the reported complaints may be arising due to faulty beliefs or relationship issues. If any of these two factors are found to be contributing to the SD, these need to be focused, and once they have been adequately addressed, the SD is to be reassessed and if present needs to be treated adequately.

In the presence of comorbid psychiatric disorder, the next step involves ascertaining whether is it primary or secondary (primary psychiatric disorder causing SD; secondary – psychiatric disorder is secondary to SD). The patient with primary comorbid psychiatric dysfunction or those who have prominent psychiatric symptoms (may be secondary in origin) first adequately treat the psychiatric disorders before focusing on the treatment of SDs.

GENERAL NONPHARMACOLOGICAL MEASURES

Sex education

Sex education or psychoeducation is the primary step for the treatment of any SD. It aims at normalization of the individual's experiences and reduction of anxiety about sex by providing accurate and scientific information. A special emphasis needs to be given to those areas which are directly related to the patient's problem. Many figures, diagrams, and reading material to couple/patient as possible for reference and illustrations are provided. The basic aim is to establish a rapport with the patient/couple and make him/her understand the problem in a language and intellectual level they understand. At least four sessions are taken to teach relaxation and provide sex education.

Never forget to address the sexual myths or misconceptions. A common problem found in a relationship or a sexual problem is a myth arising out of cultural beliefs, lack of education, religious systems, or even ignorance shown by the person himself/herself. Improper sex education is a major reason among individuals facing problems with partner about sex expectation – how, what, and when it should happen. One of the components of sex education is to help the individual and his or her partner alters any sexual beliefs that interfere with the individual's enjoyment of sex. Some of these apply equally to both men and women, while others will be more relevant to one gender than the other.

Relaxation exercises

Relaxation therapy should be taught to patient using Jacobson's progressive muscular relaxation technique or Benson Henry relaxation technique. This can be combined with the biofeedback machine so as to facilitate objective evidence and mastering of anxiety by the patient.

Specific nonpharmacological management of sexual dysfunction

The specific nonpharmacological measures vary according to the type of SD. One of the important components of the specific measures of treatment includes homework assignment for the couple. It is important to remember that many of these measures are carried out simultaneously. Table 4 highlights the key points in psychotherapeutic interventions.

Table 4.

Key points of psychotherapeutic dysfunction

| Sex therapy (dual therapy) | Brief, problem focused and behavioral approach Focus on relief of immediate symptoms which acts as a bridge between the psychoanalytic and behavioral approach The assessment and treatment need to be tailored depending upon one’s setting, profession, specialty and most important of all, the type of the problem encountered in the client Involves both partners Anatomy and physiology of sexual function are explained and doubts are cleared Emphasizes on not to blame one’s partner or oneself and that sex is a mutual act between two individuals and interpersonal communication at a highly intimate level and enhanced social communication benefits the relationship Education, heightening sensory awareness and sensate focus exercises are taught to the couple Behavioral exercises include sensate focus (nondemand pleasuring), to allow the individual to reexperience pleasure without any pressure of performance or self-monitoring |

| Behavioral techniques | Different approaches include Masters and Johnson’s approach, Kaplan’s approach and the PLISSIT model with some variations in the treatment process PLISSIT model - Proposed by Annon Graded intervention wherein individual letters stand for: P: Permission giving LI: Limited information SS: Specific suggestion IT: Intensive sex therapy Permission giving: The first phase client is assured that their thoughts, feelings, fantasies and behaviors are normal till they are not affecting the partner in a negative manner Limited information: Is the phase where the client is given information related to his/her sexual problem Specific suggestion: Behavioral exercises such as start-stop technique, “sensate focus” are taught and homework assignments are given. These help in improved communication between the couple and in learning new arousal behaviors Intensive therapy: Considered if the first three fail. Insight oriented and psychosexual approaches are taken to make the client aware of their feelings Sex therapy involves primarily sensitization, desensitization techniques. The general principles are applicable to majority of the inadequacies encountered in clinical practice. The major guidelines to be followed are (i) educating the couple, (ii) setting the framework for the therapy, (iii) prescribe sex, (iv) sensate focus exercises, and (v) systematic sensitization and desensitization: The couple is advised to talk on issues bothering them in a nonjudgmental way, encourage partners to see, hear and understand each other’s perception and teach verbal and nonverbal communication skills, in general, and during sexual activity, in particular |

| Other therapies Couple therapy and Family therapy (marital and family counseling) | The therapist works with families and couples in intimate relationships, regardless of whether the client considers it to be an individual or family issue Eclectic approach: Therapist uses a theoretical concept that leads to improvement of a couple’s relationship. Ideally, in marital therapy both partners are counseled together. It is important to first ascertain whether love and concern exists for each other Communication pattern between the couple and the power structure of their relationship needs to be ascertained. The therapist could by exaggeration highlight the method of relating to each other in a couple and their communicative pattern. The therapist by modeling demonstrates methods such as genuine listening, encouraging and empathizing by which love and tenderness can be expressed |

| Emotions focused on couples therapy | Short term intervention to reduce distress in adult love relationships and create more secure attachment bonds |

| Behavioral marital therapy | Skill oriented approach emphasizing that couples need basic skills and understanding of relationship interactions to improve their marriages The focus is the current marital relationship and improving positive communication |

| Cognitive behavioral couple therapy | Based on the concept that relationship distress includes cognitive, behavioral and affective components that influence each other |

Homework assignment for the couple

The homework assignment provides a structured approach, which allows the couple to rebuild their sexual relationship gradually. The stages of this program labeled using the terminology introduced by Master and Johnson (1970) are nongenital sensate focus, genital sensate focus, and vaginal containment. There are some basic principles of giving and carrying out the homework assignments as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Principles of giving and carrying out the homework assignments

| Components and goals of homework assignments |

| Aid in identification of specific factors (cognitions, attitudes), which may be maintaining the sexual dysfunction |

| The homework assignments also provide the couple the specific techniques to deal with particular problems |

| Important procedural aspects of homework assignments |

| The instruction needs to be detailed and precise |

| The therapist needs to always check that the couple have fully registered and understood the instructions before the treatment session ends |

| When giving instructions the therapist needs to ask the couple how they feel about the instructions and do they anticipate any difficulty. If problems are anticipated, the therapist needs to endeavor to resolve their fears before they attempt the assignment |

| A couple need not be asked to move to the next stage of the program until they have mastered the current assignments |

| A couple should never be left with the option of moving from one stage to the next between treatment sessions depending on how they progress because uncertainty can be detrimental |

| The couple need to be informed that the therapist will be asking for the detailed feedback on the progress at the next treatment session |

Nongenital sensate focus

This is the first but one of the most important assignments which can help the couple to establish physical intimacy which is comfortable and relaxed. It promotes open communication about feelings, expectations, and desires. This stage is aimed to help the partners develop a sense of trust and togetherness. By encouraging communication, increasing awareness, and relieving anxiety, intimacy among the couple is increased with understanding about each other's concerns. Abstinence from sexual activity include touching each other's genitals and the women's breast to prevent reappearance of anxiety, which is usually thought to be a very huge compounding factor in such scenarios. Promote them to enjoy general physical contact and then gradually rebuild their physical relationship. Every couple reacts variedly to these sessions according to the nature of their problem. A wide range of responses from couple vary, with some findings of this process, from very enjoyable to a complete negative reaction. In some cases, it will be appropriate for the therapist to just acknowledge the problem and reassure and encourage the couple. In some cases, therapists have to explain that it is understandable and expected, but that to overcome a sexual problem like theirs, it is necessary to approach it in a systemic fashion, and with due course of time, they will begin to get pleasure out of their sessions and these would come as spontaneous behavior.

At times, more serious difficulties in the form of negative responses to persistent breaking of the ban on sexual intercourse or irregular in homework assignments are also seen. Let the partners express their feelings and anxieties in such cases, and change focus of therapy temporarily to alleviate anxiety or misconceptions.

Genital sensate focus

The couples, who successfully go through the nongenital sensate focus sessions, need to be told to move to the genital sensate focus sessions. These sessions again depict contrasting interest of some couples as with the nongenital sensate focus, i.e., highly pleasurable to some to highly aversive to some. It is very important that the therapist specifically encourages partners to focus on pleasurable sensations as this stage is particularly likely to generate anxiety and insecurity, especially about intimacy or sexual arousal. Techniques for dealing with SDs also need to be introduced at this stage of treatment.

Vaginal containment

By now, many couples resolve their difficulties, and this stage becomes a minor protocol in such couples. This is an intermediate stage as it introduces sexual intercourse to the therapy program. For couples with dysfunctions such as ED, PME, and vaginismus, this is an extremely important stage as vaginal penetration is the key step. During a session, the couple is instructed that when they both are sexually aroused and comfortable, the women can introduce her partner's penis into her vagina. The partner is instructed to then lie still, concentrating on any pleasant genital sensations. The best position to attempt vaginal containment is female superior position or a side-to-side position. The couple should be asked to maintain containment as long as they wish, and then, they can return to genital and nongenital pleasuring. This exercise of vaginal containment can be repeated up to three times in any one session. After establishing comfort till this level, the couple can introduce movement during containment, with preferably women starting the movements first. This completes the general program of sex therapy, and now, the treatment needs to include superimposition of treatment for specific SDs. Take feedback constantly after every session and clarify any doubts or misconceptions.

Homework assignments for single male

Principles overlap for the management of SDs in single males. Provide the subject with sex education and thought relaxation exercises. Tables 6 and 7 the principles of homework assignments for single male with SD and PME. Counsel and reassure the patient in the end and encourage him to now indulge in heterosexual experience after a few days without any hurry or overt expectations. The experience should be free from guilt, fear, and anxiety to be carried out in familiar surroundings.

Table 6.

Homework assignments for single male with erectile dysfunction

| Homework assignment |

| Sexual arousal by reading erotic material or watching erotic material in books/movies and to note and focus on the sense of sexual pleasure out of the same |

| Encourage the power of imagination in subsequent sessions patient about the content of erotic material |

| In subsequent session, ask him to visualize of being involved in the same sexual activity that he imagined previously |

| If erection is perceived, it should neither make him anxious nor excited, and he should continue to concentrate on the erotic stimuli and related pleasure |

| In later sessions, patient is advised to combine reading of and seeing erotic material with his fantasy and to focus on himself in foreplay and later, intercourse |

| In subsequent sessions, reading, seeing and fantasizing is to be combined with fondling of the penis and additional masturbatory hand movements on the penis by using nondominant hand |

| Terminate masturbation before the desire for ejaculation |

| At the end of the therapy, the patient is instructed to fantasize about himself indulging in sexual intercourse with the process of ejaculation and orgasm |

| Don’ts to be followed during the initial sessions |

| Never consciously look for erection |

| If erection is attained, do not note the extent of erection |

Table 7.

Homework assignments for single male with premature ejaculation

| Don’ts to be followed during the initial sessions |

| Experimentation is not allowed during the sessions, and complete abstinence from heterosexual intercourse should be mandatory |

| Homework assignment/procedural aspects |

| Read erotic material, or see erotic material in books/movies, to visualize it and note the sense of derived sexual pleasure with subsequent erection of the penis |

| Imagine himself in the same situation |

| In subsequent sessions, combine reading/seeing with gentle touching of the penis or the testicles/groin region to enhance pleasure, but he should not stroke the penis or indulge in masturbation |

| Once, the previous step is mastered, patient is asked to combine the imagery with fondling of penis so as to build up sexual pleasure and can even indulge in masturbation |

| While masturbation, when patient has the feeling of imminent ejaculation, he is to be instructed to immediately stop masturbation and practice squeeze technique |

| At the end of the therapy the patient is instructed to fantasize about himself indulging in sexual intercourse with the process of ejaculation |

Specific nonpharmacological management for lack of sexual desire in men

Over and above the general measures, there are no particular procedures used in the treatment of this problem. Emphasis should be kept on setting the right circumstances for sexual activity, reliving anxiety, establishing satisfactory fore play, resolving general issues of relationship between couple, and focusing attention on erotic stimuli and cognitions. Usually, desire disorders have a substantially poorer response to psychotherapy (<50%) than other forms of SD (≥70%). In addition, conventional sex therapy techniques (e.g., sensate focus) are generally inadequate which makes therapy more difficult. Thus, it requires a more flexible and client-based approach to treatment.

Approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), systems approach, script modification, clinical hypnosis, guided fantasy exercises, and sexual assertiveness training have been tried by many authors with variable results.

CBT emphasizes the role of thoughts and beliefs in perpetuating the maladaptive behavior and is useful when beliefs held by the patient or couple about norms or responses are contributing to the sexual problem. The “systems” approach targets dynamics between the couple and allows assessing the extent to which SD is used by the couple to maintain a “sexual equilibrium” within the relationship (i.e., the way SD is used to regulate intimacy or to allow the share of blame between partners for the failure of the relationship).

Specific nonpharmacological management for erectile dysfunction

Men with psychogenic ED will usually start experiencing erections during either nongenital or genital sensate focus. Educate them that this has happened as a part of improvement of the treatment. Any negative suggestions of not having an erection during the initial phase can have the opposite effect. When an erection develops, men with ED often have difficulty attending to the erotic stimuli. They are focused on the quality of erection, size and girth of penis, and anxiety of maintaining the attained erection. The therapist needs to specifically encourage the man to focus his attention on the pleasurable sensations he experiences during the partner's genital caressing (the use of a lubricant can often heightens these sensations), areas of his partner's body that he finds arousing, and the pleasure of witnessing his partner's sexual arousal.

Specific nonpharmacological management for premature ejaculation

Behavioral management is the first line of therapy where ever possible. Stop–start or squeeze techniques are the specific behavioral techniques for PME. They are usually introduced during sessions on genital sensate focus.

Developed by Masters and Johnson, the stop–start technique is highly effective for the treatment of PME with up to 90% success rate. The technique focuses to increase the frequency of sexual contact and sensory threshold of the penis. It is best carried out in the context of sensate focus exercises because some males ejaculate so early that direct stimulation of the penis of any kind can trigger ejaculation straight away.

Starting with nongenital caresses allows the male more time to identify the sensations that occur immediately before ejaculation. The stop–start technique consists of the man lying on his back and focusing his attention fully on the sensation provided by the partner's stimulation of his penis. When he feels himself becoming highly aroused, he is to indicate this to her in prearranged manner at which point she needs to stop caressing and allow his arousal to subside. After a short delay, this procedure is repeated twice more, following which the woman stimulates her partner to ejaculation. At first, the man may find himself ejaculating too early but usually gradually develops control. Later, a lotion can be applied to the man's penis during this procedure, which will increase his arousal and make genital stimulation more like vaginal containment.

The squeeze technique is an elaboration of the stop–start technique, and probably, one needs to be used if the latter proves ineffective. The couple proceeds as with the stop–start procedure. When the man indicates he is becoming highly aroused, his partner should apply a firm squeeze to his penis for about 15–20 s. While applying the pressure, to inhibit the ejaculatory reflex, the forefinger and middle finger are placed over the base of the glans and shaft of the penis, on the upper surface of the penis, with the thumb placed at the base of the under surface of the glans. Repeated this three times in a session along with the stop–start technique, and on the fourth occasion, the man may ejaculate.

Both these procedures appear to help a man to develop more control over ejaculation, perhaps because he gradually acquires the cognitive techniques associated with ejaculatory control, or perhaps because he gradually becomes accustomed to experiencing sexual arousal without getting anxious. Stop–start technique and squeeze technique have been documented to have anywhere between 60% and 95% success rates.

FEMALE SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

Female SD is a highly prevalent condition that encompasses four primary domains:

HSDD

Arousal disorder

Orgasmic disorder

Sexual pain disorder.

TREATMENT OF SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

Historically, psychoanalysis was the treatment for sexual difficulties in the earlier half of the twentieth century. However, behaviorism emerged as another therapeutic option by the end of the 1960s.

The psychobiological approach emerged in conjunction with the onset of medical progression in the 1980s is still emphasized today. The treatment for SD has ultimately shifted from mental health professionals to physicians in tandem with ongoing medical advancements.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Patient and partner education

Consultations

Psychotherapy

Behavior modification

Pain management

Sexual pharmacology

Evaluate medications

Alternative medicine

Treat systemic illnesses

Structured sexual tasks

Sexual devices.

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

The cognitive behavioral treatment procedures differ among most of these sexual disorders.

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder and female sexual arousal disorder

In DSM-IV-TR, the condition of low or reduced sexual desire is referred to as HSDD and is described as “persistent or recurrent deficiency (or absence) of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity. This disturbance causes marked distress or interpersonal difficulty.”

Female sexual arousal disorder is defined in the DSM-IV-TR as “a persistent or recurrent inability to attain or to maintain until completion of sexual activity an adequate genital lubrication-swelling response of sexual excitement that causes marked distress or interpersonal difficulty.”

Treatment

Low sexual desire is a consequence of problematic functioning in other domains of sexuality, the partner relationship, or the physical and psychological condition of the female client or her partner as implicated by the circular model of sexual desire.

Treatment should focus on helping the client to increase the rewards necessary to experience stronger motivation to engage in sexual activity. The other aspects of the woman's sexual functioning such as her sexual arousal response and lubrication during sexual stimulation, her ability to experience orgasm, and reduction of pain during sex should also be emphasized.

The skills of her partner or her own erotic stimulation can be improved by treatment and thus help to relieve her partner's SD. Through nonsexual domains of the relationship, the rewards the women experiences can be increased and punishment reduced.

In a CBT of HSDD, interventions based on the sensate focus approach are often combined with other CBT interventions.

Female orgasmic disorder

Female orgasmic disorder (FOD) is described as a persistent or recurrent delay in, or absence of, orgasm following a normal sexual excitement phase, that causes marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. The DSM-IV-TR describes subtypes of FOD as (1) lifelong (primary) versus acquired (secondary) and (2) generalized (never experiencing orgasm) versus situational (reaching orgasm only with specific stimulation).

Treatment

The cognitive behavior approaches for FOD generally include behavioral exercises, such as systemic desensitization, sensate focus, and directed masturbation. It focuses primarily on changes in attitudes and thoughts decreasing anxiety and increasing orgasmic ability and sexual satisfaction

Sexual pain disorder: Dyspareunia

Dyspareunia is defined as recurrent genital pain associated with sexual intercourse that causes distress and interpersonal problems. Sexual pain is frequently associated with lack of sexual arousal/lubrication and the persistent difficulty to allow vaginal entry of a penis, and thus, the latter criteria may be difficult to establish.

The following more inclusive revision of the definition of dyspareunia: “’persistent or recurrent pain with attempted or completed vaginal entry and/or penile vaginal intercourse” has been recommended by an international consensus committee.

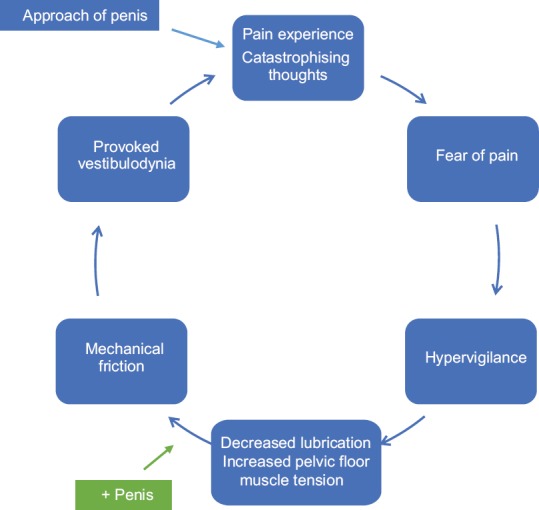

Provoked vestibulodynia disorder (PVD) was formerly referred to as vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. This is perhaps the most frequent type of superficial dyspareunia in premenopausal women. PVD is defined as burning or pain that is localized strictly to the vestibule of the vulva and is provoked by pressure or friction in the vestibule. To understand psychopathology of Dyspareunia Refer Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Psychopathology of Dyspareunia

Treatment

Achieving pain control by the woman themselves is the purpose of CBT. It focuses on reducing catastrophic fear of pain and reestablishing satisfying sexual functioning, with an aim of reducing muscle contraction in the pelvic floor and promoting lubrication during sexual activity. The ultimate goal is pain reduction during the sexual act.

CBT is often delivered in a group format, with 8–10 sessions over a 10–12-week period. The treatment package includes:

Education and information about vestibulodynia and how dyspareunia affects desire and arousal and a multifactorial view of pain

Education about sexual anatomy

Progressive muscle relaxation, abdominal breathing, and Kegel exercises

Vaginal dilatation

Distraction techniques focusing on sexual imagery, rehearsal of coping self-statements, communication skills training, and cognitive restructuring.

A behavioral intervention focuses on pelvic muscle tension, using biofeedback electromyography (EMG) with visual feedback. Women are trained to use a vaginal EMG sensor and a biofeedback device in the clinic and are then asked to complete a standard pelvic floor training program at home twice a day consisting of pelvic floor contraction exercises of various durations, separated by prescribed rest periods. Participants receive eight 45-min sessions over 12 weeks.

Specific nonpharmacological management for dyspareunia

Treatment of dyspareunia involves sex education besides general measures and sensate focus. The sex education need to focus on the aspect of adequate arousal, and the couple may also be helped by specific suggestions for modifying their usual intercourse positions. Couples should avoid positions that lead to deep penetration (such as vaginal entry from the rear) and instead adopt positions in which the woman is in control of the depth of penetration (woman on top) or in which penetration is not too deep (side-by-side or “spoons” position). Another important aspect of treatment of dyspareunia due to psychological causes helps the woman become aroused by teaching the sensate focus program.

It is likely that woman with repeated pain experience on intercourse will tense up on future occasions in anticipation of further pain. Such tension may actually increase pain as the muscles may be more resistant to penetration. Due to this, relaxation exercises before intercourse may be helpful. Progressive muscle relaxation before sexual activity may allow the women to reduce the body tension, while more specific relaxation exercises just before intercourse may help to relax the muscles around the pelvic region and may enhance arousal. A woman should acquire a number of coping techniques for minimizing the likelihood of pain. Positive self-talk may also be helpful. Such self-talk can involve the woman reminding herself that she is in control of the situation and she will be the one to determine when penetration is to occur and how deep penetration will be.

Sexual pain disorder: Vaginismus

Vaginismus is defined as an involuntary contraction of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina interfering with intercourse, causing distress and interpersonal difficulty.

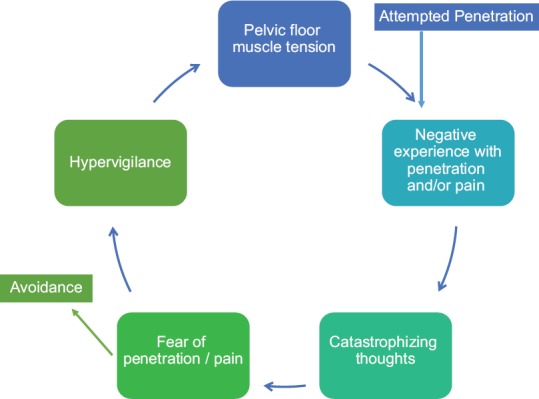

As per an international consensus committee's revised criteria, vaginismus can be defined as “persistent difficulties to allow vaginal entry of a penis, a finger, and/or any object, despite the woman's expressed wish to do so. There is variable involuntary pelvic muscle contraction, (phobic) avoidance, and anticipation/fear/experience of pain. Structural or other physical abnormalities must be ruled out/addressed.” The Circular fear-avoidance model of vaginismus is described in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Circular fear-avoidance model of vaginismus

Treatment

The use of systematic desensitization has a relatively long history in the treatment of vaginismus but has surprisingly little empirical support.

Gradual exposure exercises for homework, with gradual habituation to vaginal touch and penetration, usually beginning with the woman's fingers or artificial devices specifically designed for this purpose, are encouraged.

Specific nonpharmacological management for vaginismus

Many women who present with vaginismus have a negative attitude toward sex, and quite a few are victim of sexual assault. Some may also believe that premarital sex is wrong or sinful. This belief may be so ingrained that, even when intercourse is sanctioned by marriage, it may be difficult to relax physically or mentally during sexual intercourse. The cause of vaginismus may be a fear that is instilled by friends or family by suggesting that the first experience of intercourse is likely to be painful or bloody. Fear of pregnancy is another important cause of vaginismus.

The sex education needs to focus on clarifying normal sexuality and reducing negative attitude for sex.

The specific management involves the following stages:

The woman should be helped to develop more positive attitudes toward her genitals. After fully describing the female sexual anatomy, the therapist needs to encourage the woman to examine herself with a hand mirror on several occasions. Extremely negative attitudes may become apparent during this stage, possibly leading to failure to carry out the homework. Some women find it easier to examine themselves in the presence of the partners; others may only get started if the therapist helps them do this first in the clinic. If this is necessary, a medically qualified female therapist is to be involved

Pelvic muscle exercises are intended to help the woman gain some control over the muscles surrounding the entrance to the vagina. If she is unsure whether or not she can contract her vaginal muscles, she may be asked to try to stop the flow of urine when she next goes to the toilet. She can check that she is using the correct muscles by placing her finger at the entrance to her vagina where she needs to be able to feel the muscle contractions. Subsequently, she is advised to practice firmly contracting these muscles for an agreed number of times several times a day

After becoming comfortable with her external genital anatomy, she is advised to explore the inside of her vagina with her fingers. This is to encourage familiarity and to initiate vaginal penetration. Negative attitudes may also become apparent at this stage (e.g., concerning the texture of the vagina, its cleanliness, fear of causing damage, and whether it is “right” to do this sort of thing). The rationale for any of these objections is to be explored. At a later stage, the woman might try using two fingers and moving them around. Once she is comfortable inserting a finger herself, her partner needs to begin to do this under her guidance during their homework sessions. A lotion (e.g., K-Y or baby lotion) can make this easier. Graded vaginal dilators can be used. However, clinical experience has shown that the use of fingers is just as effective

When vaginal containment is attempted, the pelvic muscle exercises and the lotion are used to assist in relaxing the vaginal muscles and making penetration easier. This is often a difficult stage and the therapist therefore needs to encourage the woman to gain confidence from all the progress made so far. Persisting concerns about possible pain need to be explored, including how the woman might ensure that she retains control during this stage

Once containment is well established, the couple is asked to introduce movement during containment, with preferably women starting the movements first. With this, the general program of sex therapy is completed, and now, the treatment needs to include superimposition of treatment for specific SDs.

COUPLE THERAPY

Zimmer's (1997) study showed that at follow-up, women suffering from SD who received combined marital and sex therapy experienced more treatment gains. Couple therapy that addresses the specifics of the impact of SD on the marriage has been documented (Bagozzi, 1987; Zimmer, 1987; Russell, 1990).

These therapies often focus on the theme of increasing intimacy. The assumption is that if the therapy enhances intimacy between the couple, sexual satisfaction will increase. Following are therapeutic didactic models that lend themselves well to teaching and instruction.

Couples seeking therapy often are locked into a rigid belief that the partner with low desire has a problem that requires fixing. To develop new interactional rules that will support more expansive behavior, the intervening clinician requires a tool to shift the couple's thinking.

The initial step involves a therapeutic intervention employed by strategic theorists called reframing or normalization, which is used to shift the partners’ perception so that the couple can interact in a less rigid and more complex way. Reframing is successful if it manages to invest a given situation with new meaning.

This is useful because reframing allows the therapist to affirm the couple in concrete thought rather than in conjecture. Because the Basson model of the sexual response cycle can readily be described and illustrated to the couple, it facilitates joining the couple at the level of content while introducing new meaning to the couple's experience.

If accepted by the couple, it may support new behavior that will establish new patterns of mutual influence. Therefore, the therapeutic intervention of reframing/normalizing may be all that is required, regardless of whether the woman or the man of the couple presents with low desire.

TERMINATION OF TREATMENT

The termination of the treatment must be planned carefully. The various strategies and component of termination are as follows:

Prepare for termination from the start of treatment

The patient/couple should be told about the likely duration of therapy at the beginning of the treatment. Setting the time frame will encourage the patient/couple to work on the homework assignments.

Toward the end of treatment extend the intervals between sessions

The intervals between the last two to three sessions need to be extended to 2–3 weeks.

Prepare for relapse

The therapist needs to prepare the couple for relapse. About three-fourth of men will experience recurrence of their problem following treatment. Hence, treatment also needs to assist men to cope well with relapse. Most recurrences occur in a temporal pattern (i.e., will occur more at certain times than at others) and usually improve naturally or with self-initiated restart of treatment techniques. The understanding that relapses are normally expected helps to reduce the anxiety and sense of failure that may otherwise prolong erectile difficulties. The clinical practice guideline group for “Principles of Marital therapies and Behaviour therapy of sexual dysfunction” was comprised of Dr. Mrugesh Vaishnav, Dr. Gautam Saha, Dr. Abir Mukherjee, Dr. Tushar Jagawat, Dr. Navendu Gaur, Dr. Parag Shah.

Follow-up assessments

Follow-up assignments help the therapist to evaluate the short-term effectiveness of treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281:537-44. Erratum in: JAMA. 1999;281:1174–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreira ED, Glasser DB, Nicolosi A, Duarte FG, Gingell C GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Sexual problems and help-seeking behaviour in adults in the United Kingdom and continental Europe. BJU Int. 2008;101:1005–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sathyanarayana Rao TS, Tandon A. Sexual disorders. In: Munjal YP, editor. API Text Book of Medicine. 10th ed. 1, 2. Association of Physicians India; pp. 2266–75. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sathyanarayana Rao TS, Ismail S, Darshan MS, Tandon A. Sexual disorders among elderly: An epidemiological study in South Indian rural population. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;57:236–41. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.166618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avasthi A, Grover S, Sathyanarayana Rao TS. Clinical practice guidelines for management of sexual dysfunction. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:S91–115. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadock VA, Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. 18.1a. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. Normal human sexuality and sexual dysfunction; pp. 2027–59.–59. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annon JS. New York: Harper & Row; 1976. The Behavioral Treatment of Sexual Problems: Brief Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan HS. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1974. The New Sex Therapy: Active Treatment of Sexual Dysfunctions. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawton K. Symposium on sexual dysfunction. The behavioural treatment of sexual dysfunction. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:94–101. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corona G, Lee DM, Forti G, O’Connor DB, Maggi M, O’Neill TW, et al. Age-related changes in general and sexual health in middle-aged and older men: Results from the European Male Ageing Study (EMAS) J Sex Med. 2010;7:1362–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clayton AH, Hamilton DV. Female sexual dysfunction. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:323–38. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avasthi A, Banerjee ST. Chandigarh: Marital and Psychosexual Clinic, Department of Psychiatry, PGIMER; 2002. Guidebook on Sex Education. Marital and Psychosexual Clinic. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogan DR. The effectiveness of sex therapy: A review of literature. In: LoPicolo J, LoPicolo L, editors. Handbook of Sex Therapy. New York: Plenum Press; 1978. pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masters WH, Johnson V. Human Sexual Inadequecy. London: Churchill; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawton K. Sexual dysfunctions. In: Hawton K, Salkovskis PM, Kirk J, Clerk DM, editors. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Psychiatric Problems a Practical Guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinberger JM, Houman J, Caron AT, Anger J. Female sexual dysfunction: A systematic review of outcomes across various treatment modalities. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7:223–50. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank JE, Mistretta P, Will J. Diagnosis and treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:635–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stinson RD. The behavioral and cognitive-behavioral treatment of female sexual dysfunction: How far we have come and the path left to go. Sex Relationsh Ther. 2009;24:3–4. 271-85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ter Kuile MM, Both S, van Lankveld JJ. Cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual dysfunctions in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:595–610. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gehring D. Couple therapy for low sexual desire: A systemic approach. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29:25–38. doi: 10.1080/713847099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]