INTRODUCTION

Supportive psychotherapy (SP) is possibly the most ubiquitously used psychotherapy but is less researched. Since the beginning, compared to other psychotherapies, it is considered as an “inferior” therapy and is referred to as “Cinderella of Psychotherapies,” which can be used in multitude of clinical scenarios and settings. It can not only be used in outpatient setting but can be used inpatient setting, emergency setup, and consultation-liaison psychiatry setting including medical inpatient and outpatient setups. In terms of client selection, SP is mostly used as an exclusion form of therapy, i.e., clients who are not suitable for other forms of therapy, they are considered for SP. Accordingly, it can be understood as a kind of psychotherapy, which is flexible, can fit and address the needs of a wide range of clients with different diagnoses. Further, it is also often used as the initial form of therapy, before the therapist shifts to a more structured and sophisticated form of psychotherapy. Accordingly, it can be said that the basic principles of SP are at the heart of all doctor–client relationships and all forms of psychotherapies.

SP has evolved or emerged from the time of psychoanalysis. During the time when psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy were the predominant schools of psychotherapy, clinicians came across clients who were not analyzable due to various reasons, but required therapy. These clients were treated with support and suggestions, by less neutral therapist stand. However, this was not the preferred mode of therapy, for preferred client. However, still, it was provided by trained psychotherapists and was guided by the psychodynamic understanding. In this era, Glover[1] argued that neutral stance was always required for the therapy to work. It was said that therapy also worked if the therapist was enthusiastic, open and displayed genuine positive regard to the client. This kind of non-psychoanalysis treatment was understood as an equivalent of SP. In the era of psychoanalysis, everything, which was not psychoanalysis, was understood as SP.[2] However, even Freud considered that pure psychoanalysis should be mixed with some direct suggestions. Over the years, evidence emerged that SP is as effective as psychoanalysis and at times, superior to psychoanalysis.[3]

In terms of training, initially, in the era of psychoanalysis, SP was considered to be a form of therapy, which required no formal or special training. It was thought that it has nothing beyond the common sense approach with therapist having attributes of good interpersonal skills and ability to empathize. However, over the years, understanding about SP has changed. Some of the authors equate it with eclectic psychotherapy, which uses principles of different school of thoughts.[2]

Over the years, although there have been many attempts to define SP, it is believed that there is lack of a good definition for SP and most of the textbooks either do not define the term or ignore it entirely. In fact, it is most often defined by exclusion criteria. Bloch[4] defined SP as a form of psychotherapy that does not involve exploration of the unconscious, a focus on transference and an understanding by the client of their characteristic defenses. Wallace[5] defined it as a therapy to augment the clients adaptive capacity and to reaffiliate the client with others. Werman[6] defined it as a substitute treatment which supplies the client with those psychological elements which are lacking or possessed insufficiently. Dewald[7] defined SP as a therapy that is generally aimed at symptom relief and overt behavior change without emphasis on modifying personality or resolving unconscious conflicts. Pinsker[8] defined “SP as a body of techniques, or tactics, that function with various theoretical orientations as a 'shell program’ functions with a computer's operating system. A therapist's operating system is the theoretical orientation that gives direction to his or her interventions.” Recently, Winston et al.,[9] defined SP as a “dyadic treatment that uses direct measures to ameliorate symptoms and maintain, restore, or improve self-esteem, ego function, and adaptive skills. To accomplish these objectives, treatment may involve examination of relationships, real or transferential, and examination of both past and current patterns of emotional response or behavior.” As is evident from all these definition, the problem of defining SP is an outcome of frame of reference, which is considered to define it. The frame of reference has varied from objective of treatment to the techniques to be used. If one attempts to define SP, from the perspective of aim of therapy, than it should be considered as a form of therapy aimed at maintenance rather than restructuring. In terms of technique, SP is based on reflection rather than interpretation or direction. In terms of frequency of sessions, it is understood as a therapy, which can be carried out at a frequency of less than once a week, and in terms of client suitability, it is used for clients who are deemed unsuitable for other terms of psychotherapies.

As SP is used for different kind of clients, its goals are determined by the type of clients. If SP is considered for a person, who has been otherwise functioning well, but has now become symptomatic due to overwhelming stress, then the goal of SP is to restore the person to his/her previous level. However, if it is used for a client, who is not suitable for other forms of therapy, the goal of SP is palliative rather than radical, and no major life or personality changes are intended. Indeed care is taken not to disrupt reasonable defenses, the generation of conflicts is avoided, and critical feedback to the client is kept to a minimum.

Another key issue to be understood while practicing SP is to understand the difference between “being supportive” in the therapy versus “SP.” This distinction has been compared with invisible foundation on which all buildings rest and the external buttress that some, especially those in poor condition require. Support is an implicit component of all psychotherapies and comprises of the regularity, reliability, attractiveness of the therapist toward the client, and the working alliance between them. Support became a specific mode of therapy when these features occupy the foreground and in which interpretation and behavioral directions play minor roles.

In this background, the aim of this clinical practice framework is to provide an understanding of the principles of SP. This framework intends to outline the theoretical frameworks for SP, indications, strategies and tactics to be used as part of SP and techniques of SP. It is important to remember that the strategies, tactics and techniques to be used would vary from client to client and the treatment setting. There is no straight jacket recommendation for carrying out SP, and the therapists can choose the techniques to be used, depending on the need of the client, the situation, and their ease in using the same, in the framework of following the basic principles of SP. Besides the techniques described, the therapist can draw techniques from various other schools of thoughts, if they feel that, an eclectic mix of techniques will help a client.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK FOR SUPPORTIVE PSYCHOTHERAPY

In contrast to insight oriented psychotherapy, there is lack of a specific clinical theory of SP. It is suggested that practice of SP is based on the principles of self-psychology, some aspects of object relation theory, ego psychology, and the attachment theory. However, use of techniques from other school of thoughts is not contraindicated. It is not possible to discuss all these theoretical frameworks in details here. Interested readers can refer to other documents discussing these in detail. We would briefly discuss these theoretical frameworks. Self-psychology theory is based on concept of deficits and restoration. Central to this theory is the premise that in the treatment situation a “good object” is provided to the client in the person of the therapist who will be internalized, and this will mitigate or repair the deficits in the self-structure of the client, resulting from inadequate early parenting. Although Kohut is no way saw his treatment method as a type of SP, this aspect of his theory with its emphasis on therapeutic relationship is germane to a clinical practice of SP. In terms of object relation theory, a good object gradually replaces the bad object. Kohut conceived this as occurring through the therapist allowing the transference to flower, by not interpreting the client's aggression in the early phases of treatment and moving to more interpretive postures only when a good object has been internalized and replaced the degraded and deficient self-object. All these elements can be seen as applicable to an understanding of how “SP” works. The object relation therapist Fairbain emphasized the importance of the “satisfactory transference situation,” which is again consistent with the view that fostering and maintaining the positive transference is a crucial technical element in at least the earlier phase of “SP.” Other object relation therapist suggested that the therapeutic effects are a consequence of ego development resuming in therapy a result of the relationship with a new object. The ego development that may take place in therapy is not simply the internalization of interaction process between client and therapist. Thus, the therapeutic action may be viewed as a resumption of growth and the completion of development during the process of SP. Ego psychology is based on Freud's tripartite structural model of mind in which the ego is a mediator between id-impulses, the demand of reality and the strictures of the superego. The aim of psychotherapy, whether supportive or expressive, is to help the client make a better adjustment to reality. In expressive psychotherapy (EP), this is done by strengthening the ego. In contrast, SP accepts the ego more or less as it is and aims to improve adaption by modifying the demands made upon the ego. The clients are encouraged to expose themselves to less stressful situations (external reality), to be less self-critical (super ego) and wherever possible to repress instinctual demands. Attachment theory provides a more relational and interpersonal basis for psychotherapy. As such, it readily offers a theoretical basis for the role of support in psychotherapy. Attachment theory suggests that there is a lifelong psychobiological need for proximity to attachment figures at time of stress, illness, and exhaustion. The regularity, punctuality, reliability, and nonjudgmental acceptance of the therapist and therapeutic setting provide stability and support that may well be lacking in the rest of the client's life.

Accordingly, it can be said that SP aims at symptom reduction, reduction of anxiety, enhances self-esteem, by encouraging positive transference, focus on the conscious material, with avoidance of regression during the therapy and encouragement of use of mature defense mechanisms and adaptive coping mechanisms. In terms of ingredient, the common factors of psychotherapy, such as affective arousal, providing holding environment, feeling understood by the therapist, being nonjudgmental, framework of understanding, therapeutic alliance, optimism in improvement, and success experiences contribute to improvement.[2,10] SP basically involves respecting the clients with compassion, empathy, and commitment, irrespective of the fact that therapist agrees or disagrees with the clients behaviors and thoughts. Basically, the supportive psychotherapist treats the client, way they want to be treated.

Another important aspect to understand is the spectrum of psychotherapy, which is considered to extend from SP to EP, with supportive–expressive and expressive–SP in-between these 2 extremes. Clients who are most impaired are usually the candidates for SP, whereas those who are least impaired are considered for EP. Moderately impaired clients, who form the major bulk of the clinical load, are usually the candidates for supportive–expressive and expressive–SP. In clinical practice, it is suggested that most clients will require supportive–expressive psychotherapy.[9]

INDICATIONS FOR SUPPORTIVE PSYCHOTHERAPY

SP does not aim to change personality traits or defense mechanism but rather aims to stabilize them. Accordingly, it can be used in otherwise well-adjusted persons experiencing stressful situations which result in tension and distress, which is perceived as too much to be handled by the coping abilities of the person. It is also used in clients who are not suitable for other more sophisticated forms of therapies which require clients to focus on recognizing their cognitive errors, carry out homework assignments or tolerating high level of anxiety for interpretation of their behavior and defense mechanisms. It can also be used as an ego building measure, temporary expedient, in clients who lack curiosity, in clients who lack personal initiative but are interested in symptomatic change and in clients in whom other form of psychotherapy cannot be carried out due to feasibility issues [Table 1]. In terms of psychiatric disorders identified by nosological systems, it can be used in any disorder, in any age group, and also in persons experiencing subsyndromal symptoms.

Table 1.

Indications for supportive psychotherapy

| • Stressful circumstances: Such as bereavement, divorce, loss of job, menopause, physical illness, and academic difficulties |

| • Severely disturbed/poor ego strength: Those who are severely handicapped, either emotionally and/or interpersonally because of chronic schizophrenia, a chronic affective disorder or some extreme form of personally disorder. The therapist sees no prospect of fundamental improvement in these clients, but a continuing need exists to help them achieve the best adaptation possible |

| • Ego building measure: It can be used to encourage commitment to more reintegrative psychotherapeutic tasks |

| • Temporary expedient: “SP” is also indicated as temporary expedient during insight oriented therapy when anxiety becomes too strong for the coping capacities |

| • Lack of curiosity about self: “SP” is indicated for those who lack curiosity about themselves and their psychological functioning |

| • Need for symptomatic change without any self-initiative: Clients whose interest is predominantly in symptomatic change and whose capacity for self-initiating behavior is limited |

| • Feasibility issues for other form of therapies: Available resources preclude the required frequency or expenses of intensive psychotherapy |

SP – Supportive psychotherapy

EFFICACY/EFFECTIVENESS OF SUPPORTIVE PSYCHOTHERAPY

Older studies which have evaluated the efficacy/effectiveness of SP have found it useful for a variety of indications when compared with the wait listed controls. Various meta-analyses support the efficacy/effectiveness of SP for management of depression.[11,12] A recent network meta-analysis also showed that SP was as good as other forms of psychotherapy for management of depression, with all interventions having moderate to large effect sizes and the only exception to the relative efficacy was the fact that SP was relatively less efficacious then interpersonal psychotherapy.[13] In terms of management of positive symptoms of schizophrenia, SP has been shown to less efficacious than cognitive behavior therapy, but better than inactive control interventions.[14] A recent meta-analysis also showed lack of significant difference between SP and standard care in the management of schizophrenia in terms of outcome measures such as relapse, hospitalization, and general functioning. However, the authors also acknowledged that currently, the data which are available are insufficient.[15]

ASSESSMENT FOR SUPPORTIVE PSYCHOTHERAPY

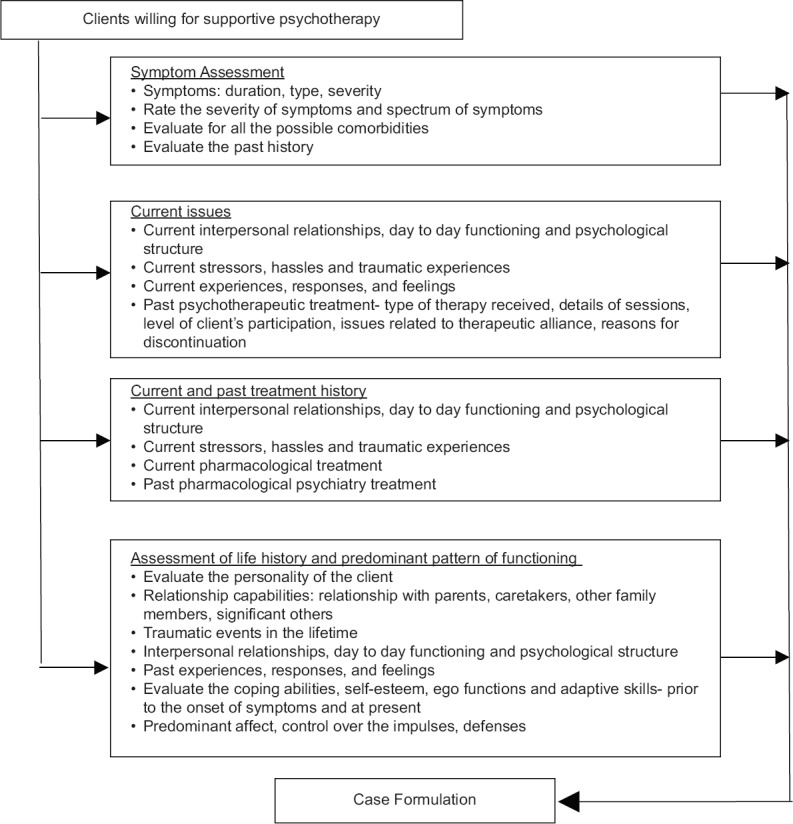

Comprehensive assessment is integral for any type of psychotherapy [Table 2 and Figure 1]. As SP is usually not the primary mode of psychotherapy, but a method of exclusion for other kind of psychotherapies, no emphasis is given for carrying out specific assessment for SP. However, this approach is incorrect. At whatever stage of management, it is decided to carryout SP, a comprehensive assessment need to be carried out, focusing on the issues important for carrying out the SP. It is generally recommended that the assessment session should last for at least an hour. However, this can be extended to more than one session, depending on the client's clinical situation and the clinical needs. At the end of the assessment, the therapist should have clear understanding of the client's current problems, interpersonal relationship issues, day to day functioning and psychological functioning. The assessment need not be limited to client's current problems, but must also focus on client's life in general. An important aspect of assessment is that it should itself be therapeutic for the client, which will enhance the therapeutic alliance and encourage the client to continue the therapy. It is suggested that use of strategies such as clarification and confrontation in empathic manner helps in proper assessment and building therapeutic alliance. However, use of these strategies should also take into account the severity of client's symptoms and the level of impairment. During the assessment, initially the therapist should focus on the presenting complaints of the clients, as these bring the client to the therapist and are the major concerns of the client. It is also important to understand the current stressors, hassles and traumatic experiences in client's life, which may be playing a role in manifestation of symptoms. After understanding the presenting complaints, the therapist should shift to the client's history both in terms of understanding the symptoms and the person. This assessment should cover the symptoms, course of the symptoms, aggravating and relieving factors and relationship issues since the early childhood to till date. It is also important to understand the traumatic experiences such as separation, loss, physical health issues, mental health issues in family members, migration, belief system of the family, educational history, sexual issues (sexual beliefs, development, orientation and experiences), identity issues, and financial situation. An attempt needs to be made to understand the client's responses and feeling about these issues. Details of past psychiatric treatment, including psychotherapeutic interventions should be obtained. In case client has received psychotherapeutic intervention in the past, therapist need to understand the type of therapy received, details of sessions, level of client's participation, issues related to therapeutic alliance, reasons for discontinuation, etc., This information can help the therapist in anticipating the problems which can arise in dealing with the client. It is also important to understand the client's coping abilities, self-esteem, ego functions and adaptive skills prior to the onset of symptoms and at present. An understanding of the client's predominant affect, control over the impulses and predominant defenses used in stressful situation is also required. Although the presence of cognitive deficits and low psychological sophistication are not contraindications for SP, understanding these can guide the therapist in choosing different strategies for the client during the therapy. A review of ongoing pharmacotherapy should also be done.

Table 2.

Assessment for supportive psychotherapy

| • Take a proper history to evaluate the clients symptoms in terms of duration, type, severity |

| • Rate the severity of symptoms and spectrum of symptoms by using appropriate scales |

| • Evaluate for all the possible comorbidities |

| • Evaluate the past history |

| • Evaluate the personality of the client |

| • Relationship capabilities: Relationship with parents, caretakers, other family members, significant others |

| • Traumatic events in the lifetime |

| • Have a basic understanding of clients current interpersonal relationships, day-to-day functioning, and psychological structure |

| • Evaluate the client’s current and past experiences, responses, and feelings |

| • Current stressors, hassles, and traumatic experiences |

| • Assess the wishes, needs, and feelings of the client towards important persons in their life |

| • Evaluate the coping abilities, self-esteem, ego functions, and adaptive skills - before the onset of symptoms and at present |

| • Predominant affect, control over the impulses, defenses |

| • Cognitive functions, psychological sophistication |

| • Current pharmacological treatment |

| • Past pharmacological psychiatry treatment |

| • Past psychotherapeutic treatment - Type of therapy received, details of sessions, level of client’s participation, issues related to therapeutic alliance, reasons for discontinuation |

| • Obtain information from caregivers, if permitted by the client and feasible |

Figure 1.

Assessment for supportive psychotherapy

Efforts must also be made to gather information from other sources, especially caregivers, with the consent of the client.

After obtaining all these information an attempt need to be made to make a case formulation for the client, as this can guide the therapy process. Case formulation is understood as an explanation for the client's current symptoms and functioning. Case formulation helps to identify the central issue. The case formulation can be based on psychoanalytic, interpersonal, object relational, or cognitive–behavioral approaches. However, it is important to remember that the formulation may have to be revised, based on availability of future information. It is generally said that good assessment itself should be therapeutic and help to mitigate the symptoms, improve self-esteem and improve adaptive skills and ego function of the client.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF SUPPORTIVE PSYCHOTHERAPY

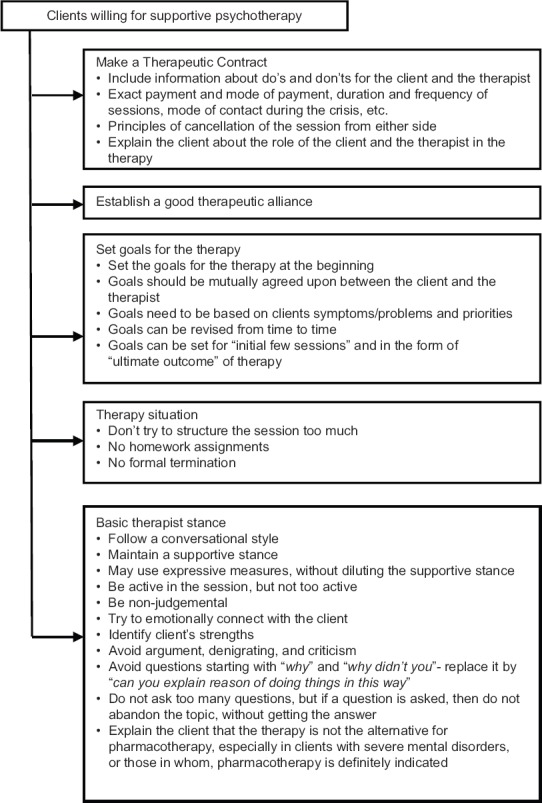

One of the most important ingredients of any psychotherapy and at the heart of SP is a good therapeutic alliance. Some of the authors suggest that the role of the therapist should be like a parent who tries to comfort the client, provides a soothing environment, encourages, nurtures, reflects containment in their behavior, sets limits, confronts the self-destructive behavior of the client, and encourages growth and self-sufficiency in the client.[16] All these features in the therapist help in building good therapeutic alliance. During the initial sessions, efforts should be directed at strengthening the therapeutic alliance with the client. It is important to sign a therapeutic contract detailing the do's and don’ts for the therapist and the client and laying down the ground rules for the therapy sessions. The contract should be signed both by the therapist and the client.

It is important to set up the goals for the therapy at the beginning. These should be mutually agreed upon between the client and the therapist. It is important to understand that while setting goals for the therapy, the goals need to be based on clients symptoms/problems and priorities. Another important aspect of setting goal is that these must be realistic, especially in clients with severe psychopathology. The goals can also set for “initial few sessions” and goals in the form of “ultimate outcome” of therapy. However, it is important to remember that the goals of the therapy may change with time and these must be revised as per the need. Other general principles to carryout SP are outlined in Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

General principles of supportive psychotherapy

| • Establish a good therapeutic alliance |

| • Preferably draw a therapeutic contract, especially, when the SP is the exclusive mode of treatment and the client is charged for the therapy |

| • The therapeutic contract should include do’s and don’ts for the client and the therapist, exact payment and mode of payment, duration and frequency of sessions, mode of contact during the crisis, etc. |

| • Number of sessions: Determined by clients need and motivation |

| • Set the ground rules, such as no physical or verbal aggression in the therapy session, not to come in intoxicated state |

| • Explain the client about the role of the client and the therapist in the therapy |

| • Set goals for the therapy |

| • Don’t try to structure the session |

| • Be nonjudgmental |

| • Try to emotionally connect with the client |

| • Identify client’s strengths |

| • Avoid argument, denigrating, and criticism |

| • Avoid questions starting with “why” and “why didn’t you” - Replace it by “can you explain reason of doing things in this way” |

| • Explain the client that the therapy is not the alternative for pharmacotherapy, especially in clients with severe mental disorders, or those in whom, pharmacotherapy is definitely indicated |

| • Follow a conversational style |

| • Maintain a supportive stance |

| • Be active in the session, but not too active |

| • May use expressive measures, without diluting the supportive stance |

| • Do not ask too many questions, but if a question is asked, then do not abandon the topic, without getting the answer |

| • No homework assignments |

| • No formal termination |

Figure 2.

General principles of supportive psychotherapy

SPECIFIC THERAPEUTIC ISSUES

SP, although is conversational in style, is a disciplined activity, and it should not be confused with normal conversation. The client is always the center of attention, the free flow of material is not essential, and the therapist must be responsive without being intrusive. The therapist must learn to employ facilitating utterances that do not appear mechanical or insincere. Even when the theoretical orientation allows the tenets of self-psychology, which places empathy in a central position, therapists have difficulty knowing what to say. The repertoire of responses may include simple reference to what the client had said in the earlier session, which makes the client feel that his/her story is known to the therapist. The therapist must master ways of maintaining a conversation by making statements that encourage responses. The therapist should learn that questions are often experienced as attacks, especially those that begin with the word “why.” If the rational for a question is not apparent to the client, it needs to be made clear to them. If the therapist is too quick to attempt interpretation or confrontation, the client may become anxious or may feel that the therapist as overpowering which can have negative impact on the self-esteem of the client. Since resolution of distortions in the perception of the therapist is not a key element of the treatment, the therapist must avoid a stance that might contribute to distortions. Positive transference is not interpreted but identified aspects of the client's relationship with the therapist may become a model for understanding interaction with other people. Praise when offered should be based on the client's values and goals, and not that of the therapist. The therapist must master techniques for ensuring that the praise is offered for only those things which client considers deserving of praise. Reframing, reassuming and instructing are accepted tactics in SP. Reframing is a legitimate therapeutic tactic, whereas contradicting can lead to a blow to the client's self-esteem. The boundary between reframing and contradicting is not always distinct and the therapist needs to be careful. When a parent or spouse repeats the same recommendation or same corrections several times, it is understood as nagging. The therapist must learn to recognize when his/her repeated good advice is likely to be experienced by the client as nagging. In general, ordinarily advice must be limited to the therapist's area of expertise and the client's need. With the most impaired clients, the therapist may suggest actions or ways of thinking about things based on his/her own good sense, and knowledge of the rules of our society. The therapist must master the skills to come with a number of alternatives rather than quick proposed solution. Ventilation is a frequently mentioned technique in SP. The client who is disorganized or labile may become more disorganized and anxious if permitted to speak at length or dwell on fantasies. The therapist need to learn to interrupt or break the flow, how to subtly encourage the client to stick with the thought, which reduce anxiety inducing disorganization. While offering reassurance, the therapist need to be honest and at times normalization of things may be reassuring for the client. Clients, who are dysfunctional, depending on their symptoms and abilities, need to be encouraged to carryout activities and interaction with others. However, this should be encouraged at a pace, which the client is comfortable and is able to handle. Many a times, providing a name to the client's problem, such as “exam related stress,” is often helpful, and this helps the client to understand their problem [Table 4].

Table 4.

Specific therapeutic issues

| • Therapist’s basic stance: Conversational, responsive, free flow of material is not essential, nonintrusive |

| • Understanding: Empathy, employ facilitating utterances that do not appear mechanical or insincere |

| • Question: Avoid questions starting with “why” |

| • Observation about underlying meaning: Avoid a stance that might contribute to distortions |

| • Transference: Positive transference is not interpreted but identified aspects of the client’s relationship with the therapist may become a model for understanding interaction with other people |

| • Ventilation: Ventilation is encouraged, but therapist must learn how to interrupt or break the flow, how to subtly encourage the client to stick to the topic, which reduces anxiety inducing disorganization |

| • Praise: Praise when offered should be based on the client’s values and goals, and not the therapist |

| • Reassurance: Be honest, normalization of things may be reassuring |

| • Encouragement: Encourage for activities and interactions |

| • Rationalizing and reframing: Avoid confrontation |

| • Arguing and nagging: Reframing, reassuming and instructing are accepted tactics in SP |

| • Advice: Limit advice to the area of expertise and the clients need |

| • Anticipatory guidance: Rehearsal of situations in advance to envisage the obstacles which might be faced in following the chosen course of action, how to deal with the obstacles |

| • Reduce and prevent anxiety: Reassurance, encouragement, lack of interrogation |

| • Naming the problem: Helps in reducing anxiety |

| • Expanding the client’s awareness: Clarification, confrontation, and interpretation |

SP – Supportive psychotherapy

STRATEGIES AND TACTICS OF THERAPEUTIC PROCESS IN SUPPORTIVE PSYCHOTHERAPY

It is important to understand the difference between strategy and tactics. The concept of strategy involves the overall plan in broad conceptual terms, whereas tactics involve specific individual interventions or therapeutic activities used by the therapist. As much as possible, the tactics should be compatible with and reflect the overall strategy, as it is through the specific tactical intervention that the strategy can be carried out. The strategies to be used for SP are presented in Table 5, and the major tactical issues that separate SP from EP are presented in Table 6.

Table 5.

Strategies for supportive psychotherapy

| • Focus primarily upon conscious problems, symptoms, thoughts, feelings, and memories |

| • The consciously experienced affect by the client should be expressed and dealt with |

| • Unconscious conflicts, affect responses and mental processes should not be explored |

| • Maintain therapeutic relationship at a positive level of rapport with deeper transference responses remaining unconscious and out of the client’s awareness |

| • Disclose the negative transference at the earliest so that it can be addressed as promptly as possible |

| • The conflicts and interpersonal relationships that are already conscious and recognized by the client are dealt within an active and continuing fashion, the therapist often using himself/herself as a model for coping with such problem |

| • Strengthen and acknowledge the useful and acceptable defense mechanisms/coping abilities |

| • Suggest new defenses/coping abilities, if the existing are maladaptive |

| • The therapists may intervene in active directive ways and may use themselves as a model for values and information |

| • The relationship between the client and the therapist is maintained indefinitely even though they may no longer meet, the aim is to foster the sense of continuity rather than a termination |

Table 6.

Tactics of supportive psychotherapy

| Tactics | SP | EP |

|---|---|---|

| Structure of the treatment situation | Flexibility is the rule, in terms of duration, frequency and setting Methods of payment can vary depending on the needs and comfort of the client | Regular and sustained therapeutic situation with prescribed times, constant duration session, methods of payment are the rule Departure from the usual structure can be used to understand some of the conflicts of the client |

| Activation of transference | Transference is maintained at dilute and unconscious level and feedback is offered promptly, as soon as possible Reality information about changes in the frame to reduce transference distortion is offered Appropriate personal information and opinion are offered Defenses are maintained against awareness and content of transference feeling or wishes Negative transference is discouraged | Activation of transference - Feedback is delayed, at least until elaboration of transference experience has occurred Personal anonymity is maintained Interest in transference phenomenon and frame of therapeutic situation is maintained, transference experiences are interpreted |

| Level of consciousness | Focus is on the issues that are already in the conscious awareness of the client | Intervention is directed toward interpreting defenses against previous unconscious conflicts |

| Identification with the therapist | Identification with the therapist in encouraged The therapist may provide personal information and responses, may advise or suggest ways of problems solving, may encourage imitation of the therapist judgment and clues and may provide active alternative understanding of the situation | Identification with the therapist in enhanced by the attitude of curiosity, willingness to suspend immediate judgment, and paucity to discuss any topic |

| Management of resistance and defenses | Defenses are in general unchallenged and maintained or even strengthened to promote more comfortable adaptation If the resistance and the defenses used by the client threaten the client’s external adjustment or therapeutic relationship, new and substitute defenses are suggested | Therapist searches for defenses and resistance against awareness or change is specifically interpreted |

| Catharsis and abreaction | Emotional responses and affects associated to already conscious memories or trauma are encouraged and are responded to in whatever way seems appropriate | Aim is to go beyond manifest emotional experiences and expression to the underlying and at times, unconscious manifestations and meanings |

| Adaptation to the clients character organization | Therapist seeks to intervene in ways familiar and compatible with the clients overall character structure, thereby striving to avoid confrontation or stress in terms of how the client characteristically interacts in various situation | Therapist intervenes in ways that are alien to the client’s character structure |

| Management of regression | Regression is minimized and where ever possible it is reversed | Regression is enhanced |

| Reinforcement | Transference relationship is used to achieve whatever goals have been set | Therapist avoids manipulating or using the transference to achieve present behavior patterns |

| Use of therapist as alter ego | Therapist may at times serve as an alter ego when the client is unable to carry out a particular activity, intervention, effort or pattern of behavior to satisfy or fulfill his or her needs In such situation therapist might act for the client by intervening in various situations, with people with whom the client is unable to maintain or establish his/her own interest and may simultaneously present a model of how one can go about resolving such problem |

Therapists specifically seek to avoid interacting for the client Clients request to therapist for intervention is interpreted |

| Use of medication | Medications are commonly used as an adjunct for the control of symptoms and alleviation of distressing behavior | The usual pattern is to avoid the use of medication, if possible |

| Insight | Insight is considered less important | Achievement of insight by the client at an emotional, as well as cognitive level is the goal of the therapy |

| Termination of therapy | Aim is more to consider interruption of therapeutic contact, rather than termination | Termination date is fixed well in advance of the actual ending of treatment, and client is allowed sufficient opportunity to activate the conflict in question |

EP – Expressive therapy; SP – Supportive psychotherapy

TECHNIQUES OF SUPPORTIVE PSYCHOTHERAPY

Various techniques [Table 7] which can be used in SP include the following:

Table 7.

Specific techniques of supportive psychotherapy

| • Guidance: Providing facts and interpretation, in matters such as education, employment, health, and social relationship |

| • Tension control: Strategies to reduce tension |

| • Environment manipulation: Focuses on defining and eliminating environmental factors disturbing the psychological balance of the client or target to address the deficits in the living situation of the client causing problems |

| • Externalization of interest: Resumption of activities which were once meaningful to the client or which help them to use their for their leisure time |

| • Reassurance: Part and parcel of all kind of psychotherapies |

| • Prestige Suggestion: Suggestions may be sometimes be used deliberately in calculated way, in the form of directions given with delivered with authoritative emphasis to influence the client’s behaviour |

| • Persuasion: Aims at building self-confidence, so that the client his or her own master. By using authority’s role, the therapist can act as a mentor to persuade the client to rethink about their views and life philosophies |

| • Pressure and coercion: These are authoritative methods that are used in a calculated way to stimulate the client towards fruitful actions |

| • Confession and ventilation: “Talking things out” or “getting things off one’s chest” |

Guidance

Guidance is aimed at addressing the specific problem that leads to distress and maladjustment. The clients are guided to detect ways, examine and avoid stressful situations. In doing so, realistically suited course of action to solve the problem is determined. One of the major drawbacks of guidance includes the authoritarian relationship established between therapist and the client which may not be good for clients with dependent traits. Another disadvantage includes development of strong sense of insecurity if the client develops doubt about strength or wisdom of the authoritative therapist.

Tension control

Various techniques such as relaxation exercises, self-hypnosis, meditation, and biofeedback can be helpful. However, it is important to remember that these are usually palliative, and their value is more when these are used along with other forms of psychotherapies.

Environment manipulation

Environmental manipulation may include techniques such as home treatment, hospitalization, day hospital care, and attending rehabilitation center.

Externalization of interest

Under stressful situations, many individuals withdraw themselves from interests that are part and parcel of healthy living. In such a situation, the clients are encouraged to resume activities which were once meaningful to them or the therapist helps them to develop new interests to fill their leisure time. The various activities which could be suggested may include sports, games, craft, photography, fine arts etc., These leisure activities, not only make the person busy, but also allow the person to express their creativity and improve their interaction with others, thereby reducing social isolation and exposing them to group dynamics. Various therapies such as occupational therapy, art therapy, music therapy, drama therapy, and social therapy are based on these principles, and these can be used as adjuncts to the other traditional psychotherapeutic interventions. Social therapy is particularly useful when normal familiar relationships, social activities and work situations lead to upsetting and self-defeating reactions in a client in spite of undergoing other forms of psychotherapy.

Reassurance

Reassurance is part and parcel of all kind of psychotherapies. The very presence of the therapist may be soothing for the client. This is true for severely upset Persuasion as a technique is based on the belief that the clients have within themselves the power to modify their pathologic emotional proneness by force of sheer will or by the utilization of common sense. Clients, who donot have the capacity to handle their anxiety by using their own resources, and look forward to seek comfort from an idealized parental figure. Verbal reassurance is often given to the clients, who verbalize doubt about their ability to get well. Reassurance may also be used for clients, who are in the grip of fears, arising out of their irrational thinking. In such a situation the therapist discusses such fears openly, offers explanations about those being baseless with the hope of diverting the client from destructive thinking pattern.

Prestige suggestion

Prestige suggestion is one of the oldest techniques which are employed as part of SP. Despite efforts by the therapists to avoid any kind of suggestions, these play an important role in every psychotherapeutic relationship. Generally, the clients have a tendency to select things, which they want to hear. At times, suggestions may be used as part of SP deliberately in the form of directives given with authoritative emphasis to influence the client is calculated ways. Symptoms that are ameliorated by suggestion probably resolve because of the unconscious need of the client to obey. Suggestion works best, where the symptoms have minimal defensive purpose and where the need for symptom free functioning is a powerful incentive. Sometimes, clients can use suggestions for themselves, which is understood as autosuggestions. Clients who are able to follow autosuggestion in the adaptive way need to be encouraged to do so.

Persuasion

Persuasion is understood as a technique, which is based on the assumption that the clients themselves have the power to modify their pathologic emotional proneness by their will power or by using common sense. As part of persuasion, the therapist may serve as a guide/mentor to make the client to revise thier views and life philosophies. The objective of persuasion is to change the habitual attitudes of the client against which the client is fighting with self and to provide them with new goals and moves to adapt to the reality.

Pressure and coercion

These are authoritative measures, which can be used in a calculated manner to stimulate the client to act in a positive way. These may be useful for some clients with dependent personalities who face life only when forced to comply. Coercion may also be used in emergencies where the individual's endanger their or others life, where other methods fails. Therapeutic pressure may be exerted in the form of assigned pursuits. It is important to remember that a these measure will not result in permanent good therapeutic effect as client will resent of being treated like a child and resultantly, with time would defy the therapist even to the point of leaving therapy. Hence, when used, pressure and coercion should be used only as a temporary measure, in critical situation.

Confession and ventilation

Confession “talking things out” or “getting things off one's chest” in a professional relationship is an important supportive psychotherapeutic technique. This allows for release of pent up feelings and emotions and the subjection of inner painful elements to objective reappraisal. The mere verbalization of things about self, of which the client may be shamed or fearful of, helps to develop a more constructive attitude towards themselves. Verbalization of fears, hopes, ambitions and demands as part of ventilation often gives relief. Verbalization of faulty ideas and beliefs also provides opportunity to the therapist to correct the misconceptions. Repeated verbalization of unpleasant and disagreeable attitude and experiences permits the client to face past fear and conflicts with lesser inner turmoil.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Glover E. The therapeutic effect of inexact interpretation: a contribution to the theory of suggestion. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 1931;12:397–411. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markowitz JC. What is Supportive Psychotherapy? Focus. 2014;12:285–89. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloch S. Supportive psychotherapy, in An Introduction to the Psych otherapies. In: Bloch S, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace ER. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1983. Supportive psychotherapy, in Dynamic Psychi atry in Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallerstein RS. New York: Guilford Press; 1986. Forty-Two Lives in Treatment: A Study of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werman DS. The Practice of Supportive Psychotherapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dewald PA. Principles of supportive psychotherapy. Am J Psychother. 1994;48:505–18. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1994.48.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinsker H. A Primer of Supportive Psychotherapy. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winston A, Rosenthal RN, Pinsker H. Introduction to Supportive Psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Battaglia J. 5 keys to good results with supportive psychotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuijpers P, Driessen E, Hollon SD, van Oppen P, Barth J, Andersson G. The efficacy of non-directive supportive therapy for adult depression: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:280–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Smit F. Psychological treatment of late-life depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:1139–49. doi: 10.1002/gps.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barth J, Munder T, Gerger H, Nüesch E, Trelle S, Znoj H, et al. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: A network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bighelli I, Salanti G, Huhn M, Schneider-Thoma J, Krause M, Reitmeir C, et al. Psychological interventions to reduce positive symptoms in schizophrenia: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2018;17:316–29. doi: 10.1002/wps.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckley LA, Maayan N, Soares-Weiser K, Adams CE. Supportive therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD004716. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004716.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misch DA. Basic strategies of dynamic supportive therapy. J Psychother Pract Res. 2000;9:173–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan PR. Learning theories and supportive psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128:119–22. doi: 10.1176/ajp.128.6.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan HS. The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry. New York: Norton; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaston L. The concept of the alliance and its role in psychotherapy: Theoreticaland empirical considerations. Psychotherapy. 1990;27:143–53. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellerstein DJ, Pinsker H, Rosenthal RN, Klee S. Supportive therapy as the treatment model of choice. J Psychother Pract Res. 1994;3:300–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmes J. Supportive psychotherapy. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167:439–45. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rockland LH. Supportive Therapy: A Psychodynamic Approach. New York: Basic Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novalis PN, Rojcewicz SJ, Peele R. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1993. Clinical Manual of Supportive Psychotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winston A, Winston B. Handbook of Integrated Short-Term Psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winston A, Pinsker H, McCullough L. A review of supportive psychotherapy. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1986;37:1105–14. doi: 10.1176/ps.37.11.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winston A, Rosenthal RN, Muran JC. Supportive psychotherapy. In: Livesley WJ, editor. Handbook of Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. New York: Guilford; 2001. pp. 344–58. [Google Scholar]